Introduction

Violent patients in the prehospital environment pose a threat to health care workers tasked with managing their medical conditions. While research has focused on methods to control the agitated patient in the emergency department (ED), there is a paucity of data looking at the optimal approach to subdue violent patients safely in the prehospital setting.

Prehospital providers have the option of physical restraints, chemical restraints, or a combination of both methods. Physical restraints provide protection for prehospital providers from physical assault. However, in order to physically restrain an agitated patient appropriately, a minimum of five people should be involved. This is not always practical in a prehospital setting. In addition, a patient who continues to be agitated while in physical restraints is at risk for rhabomyolysis, hyperkalemia, acidosis, and sudden death.

Chemical sedation provides an alternative method to subdue violent or agitated patients. However, an Advanced Life Support provider is needed to administer a sedative in the prehospital environment. Sedatives such as benzodiazepines may cause respiratory depression and hypotension. Anti-psychotics, another frequently used class of sedatives, may cause life-threatening arrhythmias, though this is a rare complication.

Current prehospital treatments are based on ED trials comparing benzodiazepines, anti-psychotics, ketamine, and droperidol, alone and in combination.Reference Isbister, Calver, Page, Stokes, Bryant and Downes 1 - Reference Li, Kumar and Thomas 10 However, sedation of agitated patients in the ED differs significantly from sedation in the prehospital environment. Several of the ED trials used intravenous (IV) agents; however, IV access frequently cannot be obtained by prehospital providers confronting a violent or agitated patient. In the prehospital setting, providers do not always have time to mix multiple medications (such as haloperidol and lorazepam) as is done commonly in the ED.

The goal of this study was to compare two intramuscular sedative agents, midazolam and haloperidol, to determine their effectiveness in the prehospital environment.

Methods

This study was a randomized, controlled, non-blinded trial comparing intramuscular midazolam and intramuscular haloperidol. This study was conducted at a single, hospital-based, Advanced Life Support service. Mercy Fitzgerald (Darby, Pennsylvania USA) Emergency Medical Services (EMS) serves nine communities in a total area of eight square miles and a population of approximately 66,000 residents. Mercy Fitzgerald EMS operates under Commonwealth of Pennsylvania Statewide protocols. Advanced Life Support protocol #8001 is entitled “Agitated Behavior/Psychiatric Disorders.” This protocol defines the treatment for dealing with agitated and violent patients (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Protocol for Agitated Patients/Psychiatric Disorders.

All patients who met the criteria for protocol #8001 were eligible for enrollment in the study. Exclusion criteria included patients under the age of 18 years old, pregnant women, and patients who had IV access. Once enrollment criteria were confirmed, the paramedics attempted to contact medical command to confirm that the patient was appropriate for enrollment in the study. If the paramedic was unable to reach medical command, the decision to enroll the patient was left up to the paramedic.

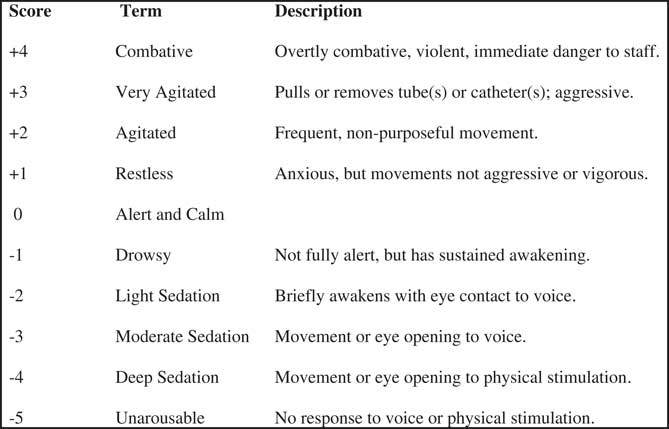

Patients were evaluated using the Richmond Agitation and Sedation Scale (RASS), a validated tool for assessing agitated patientsReference Sessler, Gosnell and Grap 11 (Figure 2). Paramedics recorded the RASS score before administering the study medication, and then again every five minutes until arrival at the hospital. On arrival at the hospital, the ED staff recorded the RASS score, and then again hourly thereafter.

Figure 2 Richmond Agitation and Sedation Scale.

Patients were randomized to either standard doses of intramuscular midazolam and intramuscular haloperidol based on the day of the week. On even days, patients were given 5 mg of intramuscular midazolam if younger than 65 years old and 2.5 mg of intramuscular midazolam if 65 years or older. On odd days, patients were given 5 mg of intramuscular haloperidol if younger than 65 years old and 2.5 mg intramuscular haloperidol if 65 years or older. Paramedics were able to re-dose the study medications after 10 minutes if the patient was not at RASS less than +1.

The paramedics recorded vital signs every five minutes until arrival at the hospital. Paramedics were instructed to obtain a 12-lead electrocardiogram, when feasible. Paramedics completed a standardized form for each patient, as well as the patients who were excluded from the study. The data from the ED were extracted from the electronic medical record.

The primary outcome measure for this study was time to reach a RASS less than +1. Secondary outcomes included: the need for additional sedation in the ED; adverse events, such as need for intubation; time between the start of the Q wave and the end of the T wave in the heart’s electrical cycle (QT interval) greater than 500 milliseconds; cardiac arrhythmias; and time until the patient was awake for discharge.

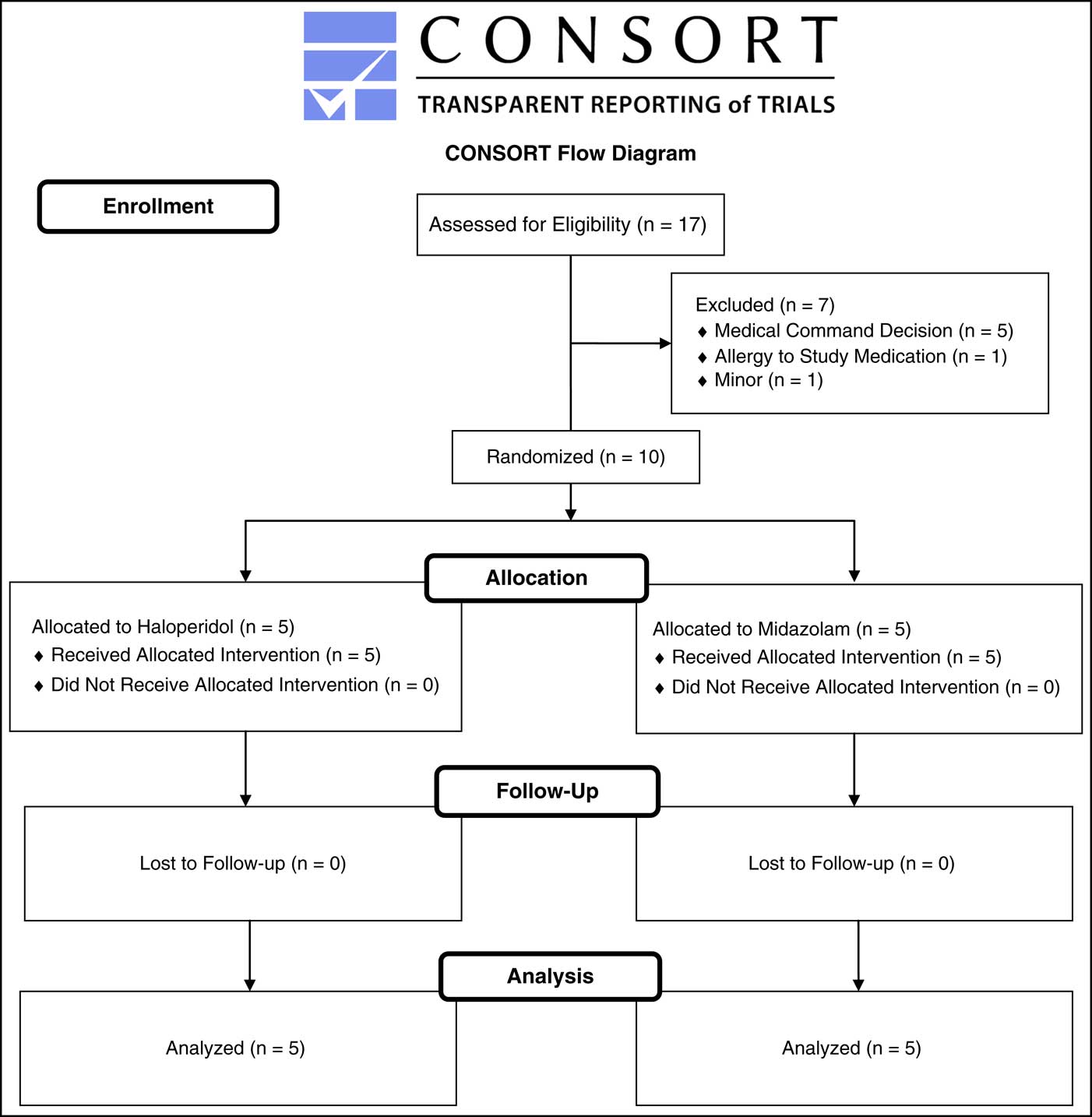

A study enrollment flow chart was prepared in accordance with the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines.Reference Schulz, Altman, Moher and Group 12 The data were recorded in a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft Corporation; Redmond, Washington USA). Data calculation was completed using Microsoft Excel.

Groups were analyzed in an intention to treat method. Data were reported in mean times with 95% confidence intervals.

This study was approved by the investigational review board of Mercy Catholic Medical Center (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania USA) and was registered as clinical trial NCT01501123 with the United States National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, Maryland USA). Interim data were provided to the investigational review board after every five patients enrolled to look for any adverse reactions of the medications.

The goal was to enroll a total of 63 patients in each arm of the study to detect a 20% difference in the primary outcome with 80% power. The study was discontinued after two years because of poor enrollment.

Results

The CONSORT diagram of study enrollment is displayed in Figure 3. Five patients received intramuscular haloperidol intramuscularly, all of whom had an initial RASS score of +4 (Table 1). The final diagnosis for four of the five patients was acute alcohol intoxication. The fifth patient was an elderly female with delirium from a urinary tract infection. Mean time to obtain a RASS score of less than +1 was 24.8 minutes (95% CI, 8-49 minutes). Two of the five patients required additional haloperidol from prehospital providers. None required additional sedation in the ED. The mean time for a patient to return to baseline mental status after receiving haloperidol was 84 minutes (95% CI, 0-202 minutes). There were no adverse effects in the haloperidol group. Emergency department information was missing on one of the five patients.

Figure 3 CONSORT Diagram. Abbreviation: CONSORT, Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials.

Table 1 Characteristics of Study Patients Abbreviations: ED, emergency department; NA, not applicable; NO, not obtained; RASS, Richmond Agitation and Sedation Scale; UTI, urinary tract infection.

Five patients were included in the intramuscular midazolam group, all of whom had an initial RASS of +4 (Table 1). No patient received an additional dose of medication from prehospital providers, though one patient required additional sedation in the ED and did not reach a RASS of less than +1. Mean time to achieve a RASS of less than +1 was 13.5 minutes (95% CI, 8-19 minutes). Mean time to return to baseline mental status was 105 minutes (95% CI, 0-178 minutes). Four of the five patients in the midazolam group had metabolic causes for their agitation, while one patient had alcohol intoxication as the cause of his agitation. No patients in the midazolam group had any adverse effects.

Seven patients were eligible for the study but were not enrolled. Five patients were excluded by medical command decision. One patient was excluded because of an allergy to haloperidol, and another patient was excluded because he was 15 years of age.

Discussion

To the authors’ knowledge, this was the first randomized controlled trial comparing two intramuscular sedative agents in the prehospital environment.

As early as 1997, Rosen et al. published a placebo-controlled trial comparing droperidol to saline.Reference Rosen, Ratliff, Wolfe, Branney, Roe and Pons 13 Twenty-three patients received IV droperidol and 23 patients received IV saline. The authors report marked improvement in agitation among patients who received droperidol without any significant side effects. Hick et al. published a case series of 53 agitated patients who were administered droperidol by paramedics.Reference Hick, Mahoney and Lappe 14 The authors found that droperidol was effective in providing sedation without complications in their cohort of patients.

Martel et al. published a before and after case series comparing their experiences with droperidol and midazolam.Reference Martel, Miner and Fringer 15 Their EMS service used haloperidol as its primary sedative agent until 2001 when droperidol received a black box warning from the United States Food and Drug Administration (Silver Spring, Maryland USA) because of QT prolongation. The EMS service then switched to midazolam for sedation. The authors reported increased rates of endotracheal intubation, need for critical care, and complications when midazolam was used compared to droperidol.

Macht et al. published a before and after retrospective case series comparing droperidol and haloperidol for sedation.Reference Macht, Mull and McVaney 16 The authors found no significant difference between the two medications in their efficacy, need for repeat sedation, or prolongation of the QT interval. Weiss et al. reported on their experiences with the addition of midazolam to a protocol for use by prehospital providers when confronted with agitated patients.Reference Weiss, Peterson, Cheney, Froman, Ernst and Campbell 17 There was decreased agitation among patients who received the midazolam.

Recently, interest has emerged in the prehospital community regarding the use of ketamine for agitated patients. Ketamine has a rapid onset of sedation, minimal hemodynamic effects, and preserves respiratory drive. Ho et al. published two cases of the successful use of ketamine in the prehospital treatment of excited delirium.Reference Ho, Smith and Nystrom 18 Burnett et al. published a case series of 13 agitated patients who were given ketamine by prehospital providers.Reference Burnett, Salzman, Griffith, Kroeger and Frascone 19 The authors reported three episodes of hypoxia, two of which required intubation. In addition, 30% of non-intubated patients required treatment for emergence reactions. Keseg et al. published their experiences using ketamine with the EMS division of the Columbus Fire Department (Columbus, Ohio USA).Reference Keseg, Cortez, Rund and Caterino 20 The authors reported data from 35 patients, the majority of which had successful sedation after the medication. However, eight patients required intubation. Kong et al. published a case series of 18 patients over three years who received ketamine for sedation in an aeromedical environment.Reference Le Cong, Gynther, Hunter and Schuller 21 The authors reported no adverse events among any of the 18 patients.

Limitations

This was a pilot study comparing intramuscular haloperidol to intramuscular midazolam in the prehospital environment. This study was limited by a small sample size. This limitation highlights the challenges of a prehospital randomized control trial. As patients could not consent for this study, enrollment was limited to patients who met very specific inclusion criteria. In addition, the two groups were not matched as to the causes of their agitation.

Conclusion

Prehospital providers safely can use intramuscular midazolam and intramuscular haloperidol for the sedation of agitated patients. No adverse effects were found with either medication. Based on the small sample size, it cannot be said that either medication is superior to other for prehospital use. Further research with larger patient samples may help to clarify the specific roles for haloperidol and midazolam in the prehospital environment.