Introduction

Based on interviews with United Kingdom stakeholders, Lee et al have highlighted four themes in emergency management in need of future research: knowledge base for emergency management, social and behavioral issues, organizational issues in emergencies, and an emergency management system.Reference Lee, Phillips and Challen 1 This comprehensive literature review addresses some of these needs through three research questions: (1) What are the basic assumptions underlying incident command systems (ICSs)? (2) What are the tasks of ambulance and medical commanders in the field? And (3) How can field commanders’ performances be measured and assessed?

The review focuses on in-the-field commanders in prehospital emergency services in the setting of mass-casualty incidents. Themes pertaining incident command in a control room setting, on a regional level, or on a national level are omitted. Research Question 1 does, however, also include elements from the broader discussion on ICSs, in which the medical and ambulance commanders play their part.

The terms “command” and “commander,” and nomenclature from the American ICS and the European Major Incident Medical Management and Support course, will generally be used in this review, except where conflicting terms from the cited literature are used to highlight differences. 2 - 3 This does not mean that the authors favor these systems over others, and this does not imply that command, control, leadership, or coordination are basically different processes.

A strain of debate concerns the appropriateness of centralization of decision making and leadership in emergencies. Incident command systems typically centralize command temporarily, but critiques argue for decentralization and decision making on the level of experts in the field.Reference Buchanan and Denyer 4 Comfort criticizes the national ICS for being too rigid and rule-bound, and for not being capable of meeting requirements of flexibility and the ability to change.Reference Comfort 5 Dynes goes as far as stating: “To create an artificial emergency-specific authority structure is neither possible nor effective.”Reference Dynes 6 Neal and Phillips challenge the command and control advocates to build “a larger database that supports the command and control assumptions,” using more rigorous research methodology.Reference Neal and Phillips 7

Quarantelli comments that successful disaster management results from organizational activity and not from planning.Reference Quarantelli 8 There is also controversy on the value of planning versus plans. Lee et al identified a further set of seemingly conflicting organizational issues: “flexible versus standardized procedures, top-down versus bottom-up engagement, generic versus specific planning, and reactive versus proactive approaches to emergencies.”Reference Lee, Phillips and Challen 1 Dynes claims that emergency planning in the US has been based on a view of “emergencies as extensions of ‘enemy attack’ scenarios,” assuming social chaos as a dependent consequence and a military-style command and control intervention as the only remedy.Reference Dynes 6 In contrast, Helsloot and Ruitenberg observed that “citizens often prove to be the most effective kind of emergency personnel.”Reference Helsloot and Ruitenberg 9 Drabek advocates “coordination and supervision” as more appropriate than “command and control.”Reference Drabek 10 Neal draws a picture of the command and control model and the emergent human resources model as “opposite ends of a continuum on managing disasters,” and comments that disasters are new experiences to individuals and societies, and therefore, foster emergent norms.Reference Neal and Phillips 7

Smith has presented a comprehensive, phenomenological study of the US National Incident Management System based on interviews with commanders with experience from working inside this system.Reference Smith 11 In that study, seven themes were identified as crucial for the understanding of command and control of multi-agency disaster response operations: experience, trust, preparedness, organization, leadership, vision, and communication.

An emergency management system must be based on available resources and competence. Prehospital emergency health services differ between countries and regions, and so do emergency management systems. Baker et al contrast the US system based on paramedics to a European tradition of bringing physicians to the street and a subsequent focus on on-site stabilization as opposed to scoop-and-run.Reference Baker, Telion and Carli 12 It is not known what constitutes the optimal emergency management system, nor is there a consensus on how effectiveness and efficiency in emergency response should be measured or evaluated.Reference Lee, Phillips and Challen 1 From a study of unsuccessful cases of emergency management, using a cultural dimension framework, Tsai and Chi found that directly implanting foreign practices would not always work.Reference Tsai and Chi 13 A review of strategies to optimize resource management in mass-casualty events found that evidence was insufficient to conclude in most cases, and that field triage systems do not “perform consistently during actual mass-casualty events.”Reference Timbie, Ringel and Fox 14 Presuming that the overall goal of emergency management is to save lives, Askhenazi et al stress that only a minor portion of casualties suffer from actual life-threatening injuries, and that these individuals must be identified and receive necessary care in time.Reference Ashkenazi, Kessel and Olsha 15 Bayram and Zuabi point out a controversy in the literature on the assumption that shorter prehospital time will give better outcomes, but confirms that this commonly is a basic premise in emergency medical systems.Reference Bayram and Zuabi 16

Crisis research reaches far and wide and cannot be considered a specific subject with a separate scientific basis. A myriad of arts and sciences are relevant to cast light on these issues, and researchers from different disciplines draw on their professional backgrounds. Comfort discusses intergovernmental crisis management as a “complex, adaptive system.”Reference Comfort 5 Berlin and Carlstöm found that actual work collaboration between agencies was “practiced to a relatively small degree” in an otherwise coordinated rescue effort, and that “repeated and well-known behavior” was preferred.Reference Berlin and Carlström 17 Amram et al presented the development of a decision support model, adding to a bulk of information and communication technology research.Reference Amram, Schuurman and Hedley 18 Bearman and Bremner have probed the field of strategies to mitigate pressures and errors on the part of incident commanders.Reference Bearman and Bremner 19 Houghton et al suggest social network analysis as a valuable tool in the study of command.Reference Houghton, Baber and McMaster 20

The nature of emergencies casts methodological challenges on the scientific development of emergency management and disaster medicine, which has been labeled a descriptive discipline.Reference Lundberg, Jonsson and Vikström 21 Sudden and unpredictable onset, involving a multitude of actors, makes it difficult to plan and conduct research according to predefined protocols. Randomized controlled trials seem extremely difficult to set up. Case studies and non-scientific reports constitute a considerable portion of published material. Buchanan and Denyer state that the research field is fragmented and characterized by “epistemological pluralism,” and claim that crisis research is “a domain in which realist-positivist and constructivist-interpretive ontologies must cohabit.”Reference Buchanan and Denyer 4 Most emergency service personnel represent professions with little academic tradition. Practitioners tend to value expertise based on practical experience and treats expertise as evidence.Reference Lee, Phillips and Challen 1 Scholars prefer published and peer-reviewed material. Journal editors’ resistance against case reports may represent a publication bias, and the peer-reviewed format might discourage contributors from the emergency and rescue professions. The following review, therefore, includes both peer-reviewed and non-peer-reviewed material.

Methods

A systematic literature search was conducted in the databases MEDLINE (Medline Industries, Inc; Mundelein, Illinois USA), PubMed (National Center for Biotechnology Information; Bethesda, Maryland USA), PsycINFO (American Psychological Association; Washington DC, USA), Embase (Elsevier; Amsterdam, Netherlands), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (The Cochrane Collaboration; Oxford, United Kingdom), Cochrane Library (The Cochrane Collaboration; Oxford, United Kingdom), ISI Web of Science (Thomson Reuters; New York, New York USA), Scopus (Elsevier; Amsterdam, Netherlands), International Security & Counter Terrorism Reference Center (EBSCO Information Services; Ipswich, Massachusetts USA), Current Controlled Trials (BioMed Central; London, United Kingdom), and PROSPERO (University of York; York, United Kingdom) covering the period up to March 1, 2014. The search was pre-planned with an aim of seeking all available studies.

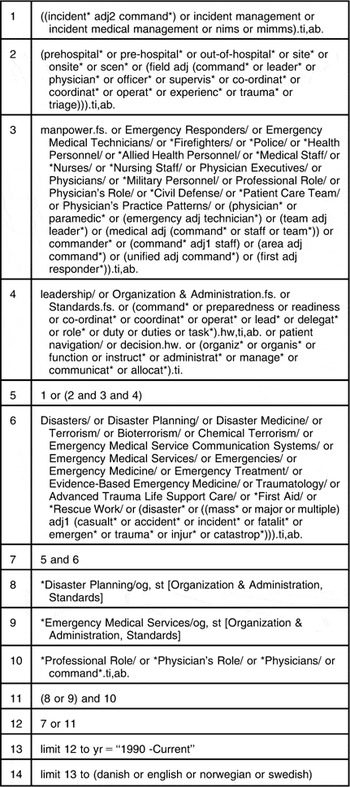

The MEDLINE search is described in Table 1, and the total database search is presented in Supplementary Material 1 (available online only).

Table 1 MEDLINE Search

Screening and eligibility assessment included literature containing descriptions or discussions of on-scene incident command, incident commanders, systems of incident management, and/or descriptions of major incident emergency response operations. Linguistic equivalents of command, commander, and management were also included (eg, coordination and leader).

There were no limitations in research method or format of publication. Inclusion was not restricted to literature pertaining to the health services. Records published before January 1, 1990, or not in English, Norwegian, Swedish, or Danish languages, were excluded. Literature restricted to an in-hospital, control room, regional, national, or community-wide setting was excluded, as was literature restricted to psychological consequences or interventions. One reviewer screened titles of all records from the database search, and then the abstracts of all records not excluded by title. Records were tracked using EndNote Version X6 (Thomson Reuters; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania USA). Records with no available abstract were included for full-text eligibility appraisal. The same reviewer hand searched reference lists of literature included for synthesis using the same inclusion and exclusion criteria, except that literature published before 1990 was also included. The cycle of screening, eligibility, and quality assessment was repeated until no new eligible articles were found.

Both reviewers assessed full-text articles and books independently. Consensus was reached, which made the planned use of a third party in case of disagreement unnecessary. Eligible full-text items were appraised for quality with weight on relevance to the research questions. No predefined appraisal tools were used. Papers were excluded if they did not discuss the research questions, as such, not implying lack of scientific quality in a broader sense. With the aim of a configurative synthesis, epistemic criteria like research design and methods used were given little weight on appraisal. Non-peer-reviewed articles and books were not excluded.

The full text of included papers and the relevant chapters of included books were then analyzed using Framework synthesis as described by Gough et al.Reference Gough, Oliver and Thomas 22 The initial conceptual framework was the three research questions themselves. Data related to each research question were extracted as citations and organized in a word processor document using Microsoft Word Version 2013 (Microsoft; Redmond, Washington USA). Key themes were identified and used to code the extracted citations. The US Department of Homeland Security's (Washington DC, USA) listing of management characteristics of the ICS (Supplementary Material 2; available online only) was used as a pragmatic starting point to code and sort the section on basic assumptions. 2 Coding was altered as new key themes emerged in the analysis process.

Reporting has been conducted using the ENTREQ checklist for enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research.Reference Tong, Flemming and McInnes 23

Results

The literature search identified 6,049 unique records, of which, 6,037 were in English (Figure 1). A total of 185 full-text articles or books were assessed for eligibility. Of these, 97 were off topic, as defined by the research questions. Quality appraisal excluded 12 papers (Supplementary Material 3; available online only).Reference Bolling, Ehrlin and Forsberg 24 - Reference Romundstad, Sundnes and Pilgram-Larsen 35 Finally, 76 articles or books, henceforth both described as papers, were included in the synthesis (Supplementary Material 4; available online only). 2 - 3 , Reference Bearman and Bremner 19 , Reference Lundberg, Jonsson and Vikström 21 , Reference Abbasi, Owen and Hossain 36 - Reference Yeager 107 Most of the included papers were written by authors working in North American or Western European institutions (Figure 2). The context of the papers was distributed between Emergency Medical Services (EMS), fire and rescue, military, police, and interdisciplinary (Figure 3). The amount of included material was fairly equal between peer-reviewed and non-peer-reviewed papers (Figure 3). The included papers were published between 1986 and 2014, but only seven papers were published earlier than 1997 (Figure 4).

Figure 1 Flow Chart of the Inclusion Process.

Figure 2 Geographical Distribution of Included Papers. Number of included papers from each continent. All American papers are from countries in North America.

Figure 3 Characteristics of Included Papers. The professional context of the 76 included papers included: Emergency Medical Services (33), fire and rescue (17), military (4), police (3), and interdisciplinary (19). The distribution between peer-reviewed and non-peer-reviewed papers is illustrated for each category. Abbreviation: EMS, Emergency Medical Services.

Figure 4 Year of Publication of Included Papers.

Discussion

The discussion section is divided into three parts: one for each research question. The first part on ICSs and their basic assumptions sets out to present the American ICS and its derivatives, and similar counterparts in other parts of the world, as does a significant amount of the included papers. The section then goes on to discuss and criticize the ICS, which is a prominent theme in the peer-reviewed literature. This includes several angles of analysis, like social network governance, resilience, high-reliability organizations (HROs), complex adaptive systems, and decision-making theory.

The second part on commanders’ tasks is richest in citations, both peer-reviewed and non-peer-reviewed. Many papers set out to clarify the commanders’ roles through descriptions of their tasks. A myriad of expressions has been summarized, and no attempt has been made to judge which ones are the better, or to develop the nomenclature as such. This is beyond the scope of a configurative synthesis.

The third part on measuring and assessing field commanders’ performances is relatively short, reflecting the scarcity of literature on this topic.

What are the Basic Assumptions Underlying Incident Command Systems?

The American ICS uses five standard, structural components: command, operations, planning, logistics, and finance/administrations,Reference Walsh and Christen 104 which “groups similar functions into subordinate management units.”Reference Morris 76 A key organizational feature of ICS is that it can be applied with one commander executing leadership of all functions, or expanded as required to a multi-layered organization with numerous modules,Footnote * giving organizational flexibility and adaptability. 97 , Reference Stumpf 99 - Reference Terwilliger 100

A larger organization means the commanders work more through branch leaders,Reference Mack 72 the competence of which affects the outcome of the operation.Reference Sachs 93 In systems with prehospital physicians, the ambulance commander and the medical commander work as a command team, with different solutions as to who is subordinate to whom. 3 , Reference Carron, Reigner and Vallotton 50 The modular expansion of the response organization may, to a large degree, be guided by the principle of “manageable span of control.”Reference Buck, Trainor and Aguirre 48 , Reference Christen and Maniscalco 51 - Reference Ciottone, Darling and Anderson 52 , Reference Morris 76 , 97 , Reference Terwilliger 100 The number of individuals manageable by one leader is three to five,Reference Walsh and Christen 104 ideally five,Reference Goldfarb 58 or three to seven. 101 Each individual emergency response worker will have one superior, which gives a chain-of-command through the entire organization.Reference Buck, Trainor and Aguirre 48 , Reference Christen and Maniscalco 51 - Reference Ciottone, Darling and Anderson 52 , Reference Morris 76 , 97 , Reference Terwilliger 100 Without this, Morris predicts “considerable confusion and chaos, and total inefficiency.”Reference Morris 76 Some suggest each sector commander needs an aid “to make sure actions occur according to plan and attention is paid to even the smallest of details,”Reference Heightman 62 or to take care of radio transmissions.Reference Phelps 83

An organized, structured, and standardized approach to incident emergency response is considered necessary by many. 2 , Reference Bea 43 , Reference Brown 47 , Reference Hayward 61 , Reference Hogan and Burstein 65 , Reference Morris 76 The ICS is claimed to be based on universally applicable management principles and is constructed to be applicable to all types and sizes of events and situations. 2 , Reference Christen and Maniscalco 51 - Reference Ciottone, Darling and Anderson 52 , Reference Goldfarb 58 , Reference Limmer, Mistovich and Krost 70 , 79 Moynihan points out there is “little empirical evidence as to whether this assumption is accurate.”Reference Moynihan 77 Wenger et al discuss several problems with the ICS and stress that “there is little positive evidence from our and other research that there can be ‘one model’ that can be utilized in all disasters by all groups.”Reference Wenger, Quarantelli and Dynes 106 Buck et al suggest that “part of the reason for the controversy is that localized emergencies are the most common responses experienced by official first responder organizations, and in these responses, ICS is useful, while scholarly writers have in mind more complex disaster occasions, a context where ICS usefulness is more questionable.”Reference Buck, Trainor and Aguirre 48

From focus groups, King et al found 138 attributes that were held to distinguish effective from ineffective responders and leaders in disasters.Reference King, North and Larkin 67 This “included knowledge, skills, attitudes, behaviors, and personal characteristics.”Reference King, North and Larkin 67 A challenge for commanders is to find the correct balance between “expression of command” and “freedom of action.”Reference Pigeau and McCann 84 Stambler and Barbera found that, despite being a common claim, there was “no direct or purposeful linkage to military command models during the development of ICS.”Reference Stambler and Barbera 96 The ICS is based on common terminology across agencies,Reference Christen and Maniscalco 51 - Reference Ciottone, Darling and Anderson 52 , Reference Terwilliger 100 including, in some cases, “common terms for equipment and supplies.”Reference Buck, Trainor and Aguirre 48 Maniscalco and Christen comment that “some people get extremely agitated over terminology,” which tends to be adjusted to locally experienced needs.Reference Maniscalco and Christen 73 The tricky part of several agencies working together seems to be the linking of their agency internal chains-of-command and secure information sharing.Reference McMaster and Baber 75 The ICS tries to solve this by a unified command structure, where commanders are joined in a command team.Reference Christen and Maniscalco 51 - Reference Ciottone, Darling and Anderson 52 , 54 , 97 , Reference Terwilliger 100 , Reference Vernon 103 Wenger et al, in contrast, find “there is little place in the ICS for inter-organizational coordination.”Reference Wenger, Quarantelli and Dynes 106 In a large-scale exercise, Helsloot found that “multidisciplinary coordination of the activities of the emergency services was limited,” but noteworthy, also found that “this did not impede the effectiveness of each service's mono-disciplinary response.”Reference Helsloot 64 The procedure manual of London Emergency Services Liaison Panel (London, United Kingdom) recognizes that commanders in the early stages of an operation are “fully occupied with their own sphere of activity,” which will delay the formation of a coordination group. 71

Command should be established and communicated by the first arriving units, as the first minutes are considered extremely important for setting the stage of the entire operation,Reference Kelley 66 , Reference Lennquis 69 , Reference Mack 72 , Reference Morris 76 , Reference Peleg, Michaelson and Shapira 82 , Reference Terwilliger 100 , Reference Vernon 103 then possibly transferred to more-trained personnel arriving later.Reference Buck, Trainor and Aguirre 48 , Reference Terwilliger 100 Rake and Njå found that commanders generally would need a good 15 minutes to “grasp the big picture after they arrived on scene,” and “did not understand the situations before the response units were in full action.”Reference Rake and Njå 85 Commanders are expected to set objectives,Reference Terwilliger 100 to “focus the response,”Reference Brown 47 and “create a cohesive joint tactical response.” 71 It seems to be accepted that organizations must have incident response plans that are known and trained, and that an incident action plan is developed to guide the response in each case.Reference Barishansky and O'Connor 42 , 54 , 79 , Reference Terwilliger 100 Some authors underscore the need to focus planning on rapid evacuation of casualties.Reference Abbott 37 , Reference Limmer, Mistovich and Krost 70 , Reference Peleg, Michaelson and Shapira 82

Training and exercise are highly valued to prepare for major incidents.Reference Bigley and Roberts 44 , Reference Brown 47 - Reference Buck, Trainor and Aguirre 48 , Reference Kelley 66 , 79 , Reference Rubin and Maniscalco 87 Some favor the use of daily routines in incident command and recommend the use of ICS principles on the smallest of incidents to make this the daily routine.Reference Christen and Maniscalco 51 , Reference Fisher 55 , Reference Lennquis 69 - Reference Limmer, Mistovich and Krost 70 , Reference McCarthy, McClure and Heightman 74 , Reference Paton, Flin and Violanti 81 , Reference Streger 98 A contrasting view is that incident command is a distinct discipline with its own set of specific competencies, and that the speed of transition from routine to crisis operations in an organization “is a major determinant of whether an incident will be managed effectively.”Reference Flin and Arbuthnot 57

An important component of the system is management and allocation of resources, including mobilization of resources and supplies.Reference Christen and Maniscalco 51 - Reference Ciottone, Darling and Anderson 52 , 54 , Reference Rüter, Nilsson and Vikström 91 , Reference Terwilliger 100 Briggs foresees a lack of supplies and personnel if teams are to work outside the ICS structure.Reference Briggs 46 Abbasi et al found that incident management teams do not focus on resource shortage and “make do with what they have available to them at the time.”Reference Abbasi, Owen and Hossain 36

The ICS organizational model may be described as hierarchicalReference Fisher 55 , Reference Groenendaal, Helsloot and Scholtens 59 and based on bureaucratic principles.Reference Buck, Trainor and Aguirre 48 The hierarchical model has been viewed positively by response practitioners who have “focused on the command and control value of ICS,” and has been criticized for “lack of focus on coordination between organizations and levels of government responding to disaster.”Reference Buck, Trainor and Aguirre 48 Moynihan emphasizes the “network structural form” of multiple organizations in a large-scale emergency response operation, finding that “any crisis response using the ICS therefore reflects an intriguing mixture of network and hierarchy.”Reference Moynihan 77 This is supported by Dudfield, pointing out that the “two models are not antithetical, although they may appear so.”Reference Dudfield 53

Abbasi et al take the social network analysis perspective, from where “simple static networks frequently perform better when they have a centralized actor as the manager and coordinator of the network; while in the case of complex and dynamic networks, decentralization can frequently yield better results” through adaptive behavior.Reference Abbasi, Owen and Hossain 36 In a complex adaptive system, initiative that is distributed rather than centralized “is a source of great strength and energy for any organization, especially in times of crisis.” 101 Groenendaal et al find from literature “little empirical evidence to support the assumption that frontline responders can be hierarchically controlled during the first phase of large-scale emergencies.”Reference Groenendaal, Helsloot and Scholtens 59

In contrast to the general focus on getting triage right and doing things right the first time, Aylwin et al favor the resilience concept by recognizing that “over triage rates will rise when casualty clearance from a hazardous scene is the priority, and this situation must be compensated for by reducing surge and increasing surge capacity at other stages of disaster response.”Reference Aylwin, König and Brennan 41 The emergency response organization can be viewed as a HRO “able to capitalize on efficiency and control benefits of bureaucracy.”Reference Bigley and Roberts 44 Owen found from ergonomic HRO research a focus on dynamic environments, complex coordination, and interdependencies.Reference Owen 80

On-scene commanders must make decisions in stressful environments characterized by: “time pressure, ill-structured problems, action/feedback loops, high stakes and multiple players, and organizational goals and norms;”Reference Van den Heuvel, Alison and Crego 102 “serious threats and requiring urgent responses;”Reference Rake and Njå 85 “shifting ill-defined or competing goals;”Reference Ash and Smallman 40 factors like noise, reduced visibility, heat, and stressful responsibility;Reference Paton, Flin and Violanti 81 “imposition of organizational norms from above” and “bottom-up pressure;”Reference Burke 49 and “extremely difficult decisions, characterized by ambiguous and conflicting information, shifting goals, time pressure, dynamic conditions, complex operational team structures, and poor communication and circumstances where every available course of action carry significant risk… now regarded as typical of situations requiring naturalistic decision making.”Reference Flin 56 As opposed to analytical decision making, “where the officer must think about a number of possible courses and then select the best option,” recognition-primed decision making is swift and, by practitioners, referred to as “intuition or gut feel.”Reference Paton, Flin and Violanti 81 Ash and Smallman found incident ground cues like smell, colors, sounds, and radiated heat to be “playing a key role in incident ground [decision making].” Commanders would also typically decide on one set of action, and then “re-evaluate the method of work as events unfolded.”Reference Ash and Smallman 40

Rake and Njå observed that commanders often choose to monitor the crews’ activities and make few decisions.Reference Rake and Njå 85 Van den Heuvel et al's informants held that “prolonging or avoiding the decision would be the biggest mistake novices would make.”Reference Van den Heuvel, Alison and Crego 102 Flin and Arbuthnot highlight that “although it may appear that a decision has to be taken immediately, this may not be the case. The skilled… commander will be able to identify when this is the case and when it is not.”Reference Flin and Arbuthnot 57 Commanders’ decisions “are not made in a vacuum, but rather in close cooperation with the other actors on scene.”Reference Rake and Njå 85 Helsloot further found that “the decisions of the disaster staff were no more than a confirmation of decisions taken at the scene of the disaster” due to the fact that commanders were fully occupied with tasks at hand and did not give priority to communication with off-scene staff.Reference Helsloot 64 Distributed decision making “assumes that it is impossible to understand and control all of the different and complex aspects of dynamic organizations through a centralized decision-making process,” and proposes that each individual unit should make its own decisions as independently as possible within the main outlines of the overall goal.Reference Groenendaal, Helsloot and Scholtens 59

What are the Tasks of Ambulance and Medical Commanders in the Field?

A prerequisite for command is some sort of overview of the incident scene. The process of getting this overview is called a scene size-up,Reference Goldfarb 58 , Reference Mack 72 , Reference Yeager 107 assessment, 3 , Reference Adesunkanmi and Lawal 38 , Reference Flin and Arbuthnot 57 , Reference Russel 88 , Reference Rüter, Nilsson and Vikström 91 evaluation,Reference Flin 56 - Reference Flin and Arbuthnot 57 , Reference Morris 76 , Reference Peleg, Michaelson and Shapira 82 , Reference Wang, Ma and Hanson 105 (problem) identification,Reference Brennan 45 , Reference Carron, Reigner and Vallotton 50 , Reference Peleg, Michaelson and Shapira 82 , Reference Wang, Ma and Hanson 105 or survey.Reference Lennquis 69 Though the commander often will physically move around the incident scene to get an overview, scene assessment may be performed through the eyes and ears of the first units on scene or medical teams present.Reference Mack 72 , Reference Peleg, Michaelson and Shapira 82 Items or themes to be assessed may include the “nature and scope” of the incident,Reference Goldfarb 58 hazards and risks,Reference Goldfarb 58 , Reference Wang, Ma and Hanson 105 need for mobilization and deployment of medical resources,Reference Russel 88 and number of patients, extent of injuries, or medical issues in general. 3 , Reference Fisher 55 , Reference Goldfarb 58 , Reference Peleg, Michaelson and Shapira 82 , Reference Rüter, Nilsson and Vikström 91 A priority concern in the emergency operation should be the safety of rescuers on scene.Footnote †

Scene assessment can also be seen as the ongoing process of monitoring the development of the situation. 3 , Reference Yeager 107 Detailed instructions on task performance are not to be given by commanders. Commanders monitor and review operations,Reference Carron, Reigner and Vallotton 50 , Reference Flin 56 - Reference Flin and Arbuthnot 57 , Reference Kelley 66 , Reference Morris 76 , 97 , 101 ensuring that quality of care, and that plans and intentions, are followed. 3 , Reference Carron, Reigner and Vallotton 50 , Reference Morris 76 , 79 , Reference Rüter, Nilsson and Vikström 91 Supervision is given, where needed, for execution of assigned tasks, 97 , 101 revision of plans may be necessary, and staff may have to be exchanged if they are not “functioning properly.”Reference Flin 56 - Reference Flin and Arbuthnot 57 , Reference Lennquis 69 , Reference Morris 76

Commanders make decisions on behalf of the whole organization. Decision making is described as immediate,Reference Carron, Reigner and Vallotton 50 in the heat of the moment,Reference Paton, Flin and Violanti 81 dynamic,Reference Van den Heuvel, Alison and Crego 102 high-risk with life-and-death outcomes,Reference Flin and Arbuthnot 57 and based on incomplete information and ambiguous intelligence.Reference Paton, Flin and Violanti 81 This is a defining task of commanders.Reference Barishansky and O'Connor 42 , Reference Morris 76 - Reference Moynihan 77 , Reference Phelps 83 , 101 Competencies to make decisions include “the ability to assess available time and level of risk,”Reference Paton, Flin and Violanti 81 managing personal stress,Reference Flin and Arbuthnot 57 and “handling multiple, demanding problems concurrently.”Reference Flin and Arbuthnot 57 Christen and Maniscalco warn, “checklists tend to fail,” and discourage attempts to reduce incident management to a matter of following checklists.Reference Christen and Maniscalco 51

Leadership of an emergency operation needs some sort of underlying idea of how the operation should be executed. This may be expressed as an incident action plan or just “plan,”Footnote ‡ strategy,Footnote § tactic,Reference Maniscalco and Christen 73 , 79 , Reference Sideras 95 , 97 level of medical ambition,Reference Lundberg, Jonsson and Vikström 21 , Reference Gryth, Rådestad and Nilsson 60 , Reference Rüter, Örtenwall and Wikström 89 - Reference Rüter, Nilsson and Vikström 91 guidelines,Reference Lundberg, Jonsson and Vikström 21 , Reference Gryth, Rådestad and Nilsson 60 , Reference Rüter, Örtenwall and Wikström 89 - Reference Rüter, Örtenwall and Wikström 90 priorities,Reference Arbuthnot 39 , Reference Rüter, Nilsson and Vikström 91 , Reference Sideras 95 , 97 tasks and activities,Reference Maniscalco and Christen 73 , Reference Rüter, Nilsson and Vikström 91 , Reference Sideras 95 objectives,Reference Sideras 95 or any combinations of these. It is worth noting that one may be expected to develop a strategy, a tactic, and tasks, regardless of the definition of the level of command as tactical, operative, or otherwise. The official termination of a major incident emergency response is a queue to involved organizations and personnel to return to normal operations. This is considered a commander task.Footnote ** The declaration of a major incident may also be the task of a commander. 3 , Reference Lennquis 69

The main tools for conducting an emergency response operation are personnel, vehicles, and equipment. An emergency service commander takes the responsibility for all medical resources at the scene.Reference Adesunkanmi and Lawal 38 , 71 , Reference Russel 88 Where both a medical commander and ambulance commander are present, the medical commander will typically manage nurses and doctors. A considerable task for commanders is to spatially and functionally distribute or allocate available resources across the incident ground to get the job done,Footnote †† but also to request additional or special resources and supplies, if needed.Footnote ‡‡ The balance between keeping resources at the scene and using them for patient transport is a crucial decision point.Reference Lennquis 69 The incident ground can be divided into “working regions” or “sectors,” both an organizational and a spatial term.Reference Carron, Reigner and Vallotton 50 , Reference Peleg, Michaelson and Shapira 82 Some functions will be tied typically to a designated area: vehicle staging, 3 , Reference McCarthy, McClure and Heightman 74 , Reference Sachs 94 , Reference Vernon 103 treatment area or casualty clearing station, 3 , Reference Lennquis 69 , 71 , Reference McCarthy, McClure and Heightman 74 , Reference Sachs 93 morgue,Reference Sachs 93 access and egress routes, 3 and ambulance loading zone.Reference Lennquis 69 Commanders must also position themselves, often at a command post or command position. 3 , Reference Christen and Maniscalco 51 - Reference Ciottone, Darling and Anderson 52 , Reference Kelley 66 , Reference Morris 76 , 79 , Reference Vernon 103

With a growing number of personnel at the scene, the organization should be expanded with functional (and if needed, spatial segment) units with subordinate commanders or unit leaders.Footnote §§ Such units may include triage,Reference Heightman 63 , Reference McCarthy, McClure and Heightman 74 treatment,Reference Heightman 63 , Reference McCarthy, McClure and Heightman 74 transport,Reference Heightman 63 , Reference Lennquis 69 , Reference McCarthy, McClure and Heightman 74 staging,Reference Heightman 63 , Reference McCarthy, McClure and Heightman 74 and communications.Reference McCarthy, McClure and Heightman 74 Where separate unit leaders for each of these function are not needed, Christen and Maniscalco suggest delegating responsibilities for all functions to a specific subcommander, along with other functions.51 Doctors and nurses at the scene may be delegated key roles as medical advisors to unit leaders, or function as leaders themselves.Reference Aylwin, König and Brennan 41 , Reference Russel 88 , Reference Sachs 93 Arbuthnot declares “Commanders may also need to consider whether there is a need for a… strategic level of command.”Reference Arbuthnot 39

Key tasks for the medical part of an emergency response operation are triage, treatment, and transport. 3 , Reference Adesunkanmi and Lawal 38 , Reference Goldfarb 58 , Reference Hogan and Burstein 65 , Reference Lennquis 69 , 71 , Reference Russel 88 Treatment and transport to health care facilities are the mitigation activities of the health services.Reference Brennan 45 Triage, staging, traffic control, infrastructure, and equipment are tasks aimed at supporting the mitigating functions. Commanders ought not to be involved directly in these tasks.Reference Fisher 55 The task of commanders is to assign practical tasks to appropriate subcommanders, or individual personnel, as appropriate, based on prioritization of tasks and assessment of availability of resources.Footnote *** With assignment of duties should follow “the delegation of authority necessary to accomplish the assignments.”Reference Murphy 78 Commanders are expected to document the course of the emergency operation, including task accomplishment, communication, and decisions.Reference Barishansky and O'Connor 42 , Reference Rüter, Nilsson and Vikström 91 , Reference Sachs 93 , 97 Documentation provides accountability and enables post-incident audit.Reference Ciottone, Darling and Anderson 52 , 79

Casualties with significant trauma, or otherwise in need of hospitalization, must be distributed to the right hospital. In more remote areas, and in countries with few and larger hospitals, all patients may be distributed to just one hospital. When more than one hospital is involved, the distribution may be determined by an emergency service commander, 3 , Reference Carron, Reigner and Vallotton 50 , Reference Goldfarb 58 , 71 , Reference Peleg, Michaelson and Shapira 82 , Reference Rüter, Nilsson and Vikström 91 , Reference Sachs 93 or by the medical commander or ambulance commander specifically.Reference Adesunkanmi and Lawal 38 , Reference Fisher 55 Distribution criteria may be necessary hospital specialties or resources to meet the individual patient's needs,Reference Carron, Reigner and Vallotton 50 , Reference Fisher 55 , Reference Sachs 93 each hospital's current bed availability or receiving capacity,Reference Fisher 55 , Reference Peleg, Michaelson and Shapira 82 , Reference Sachs 93 and “overall impact on the EMS system.”Reference Sachs 93 Not all hospitals have the capability to receive patients from a mass-casualty incident. 71

Communication is another core task of commanders, 3 , Reference Abbasi, Owen and Hossain 36 , Reference Adesunkanmi and Lawal 38 , Reference Brennan 45 , Reference Carron, Reigner and Vallotton 50 , Reference Flin 56 - Reference Flin and Arbuthnot 57 , Reference Rüter, Nilsson and Vikström 91 including “information management” and “gathering and analyzing information.” 101 , Reference Wang, Ma and Hanson 105 Information that needs to be communicated includes: the incident address or position,Reference McCarthy, McClure and Heightman 74 type of event,Reference Peleg, Michaelson and Shapira 82 situation reports,Footnote ††† resource requirements,Reference Peleg, Michaelson and Shapira 82 , Reference Russel 88 plan or strategy,Reference Bearman and Bremner 19 , Reference Murphy 78 - 79 distribution of patients to hospitals,Reference Russel 88 casualty figures,Reference Fisher 55 logistical and clinical information on individual patients,Reference Fisher 55 , Reference Russel 88 , Reference Rüter, Nilsson and Vikström 91 task assignments and instructions,Reference Legemaate, Burkle and Bierens 68 , 101 and vulnerability and risks. 79 Liaison with collaborating agencies (police, fire and rescue, and others) through their commanders, is highlighted.Footnote ‡‡‡ Likewise, the vertical communication within the health services on- and off-scene is: dispatch/alarm/communication center or strategic level of command,Footnote §§§ subordinate on-scene commanders,Reference Christen and Maniscalco 51 , Reference Murphy 78 - 79 , Reference Sachs 93 receiving hospitals, 3 , 71 - Reference Mack 72 and other off-scene medical resources. 71 Emergency services commanders have an obligation to give information to media, whether this is given directly or in coordination with other agencies, 3 , Reference Lundberg, Jonsson and Vikström 21 , Reference Carron, Reigner and Vallotton 50 - Reference Christen and Maniscalco 51 , Reference Gryth, Rådestad and Nilsson 60 , Reference Rüter, Örtenwall and Wikström 89 - Reference Rüter, Örtenwall and Wikström 90 or is limited to “authorizing the release of information.”Reference Ciottone, Darling and Anderson 52

How can Field Commanders’ Performances be Measured and Assessed?

Measurement or evaluation of the commanders’ efforts is difficult to conduct in a scientific way.Reference Lundberg, Jonsson and Vikström 21 , Reference Gryth, Rådestad and Nilsson 60 , Reference Rüter, Örtenwall and Wikström 89 There are no widely acknowledged measurement tools or validated research instruments available.Reference Legemaate, Burkle and Bierens 68

One way to approach this problem area is to use validated performance indicators.Reference Carron, Reigner and Vallotton 50 A Swedish expert group has developed a set of such indicators specifically designed to evaluate prehospital command and control in multi-casualty incidents, and demonstrated its feasibility in exercises.Reference Lundberg, Jonsson and Vikström 21 , Reference Gryth, Rådestad and Nilsson 60 , Reference Rüter, Örtenwall and Wikström 89 - Reference Rüter, Örtenwall and Wikström 90 The indicators focus on reporting from the incident scene to the dispatch center, information sharing, and time stamps. A wider set of indicators were developed in a related Delphi process, which included more time stamps and several indicators not directly connected to the commanders’ performance.Reference Rådestad, Jirwe and Castrén 92 Locally used indicators have also been published in other European countries.Reference Burke 49 , Reference Legemaate, Burkle and Bierens 68 None of these seem to have been internationally recognized or adopted.

Some authors highlight the overall impression of the emergency response as a measure of its success. The response operation should be like a “perfectly conducted orchestra,”Reference Heightman 63 “orderly and systematic,”Reference Kelley 66 “calm a tense situation,”Reference Kelley 66 “start, stay, and end under control,”Reference Rubin and Maniscalco 87 “the first responders felt satisfied about the job performed,”Reference Rake and Njå 85 “a good result at the same time as the people feel good,”Reference Rüter, Nilsson and Vikström 91 and with “overall successful resolution.”Reference Carron, Reigner and Vallotton 50 Indirectly, the success of the overall operation would be considered a measure of the commanders’ performances. Yeager goes as far as recommending help should be called for in increments, as this “allows a smooth building” of structure.Reference Yeager 107

Emergency response success could further be indicated by lives saved, delivery of the best possible emergency medical care, or property conservation.Reference Ciottone, Darling and Anderson 52 - Reference Dudfield 53 , Reference Heightman 63 , 71 , Reference Rake and Njå 85 , Reference Sachs 93 , Reference Wang, Ma and Hanson 105 Rüter et al specify that the patients should not only be alive when reaching hospital, but “leave the hospital alive and without suffering complications.”Reference Rüter, Nilsson and Vikström 91 Aylwin et al argue that the emergency response, in most cases, “can only have a minimum effect on the numbers of deaths at scene, but some reduction in immediate mortality could be achieved.”Reference Aylwin, König and Brennan 41 This further implies that most patients actually can await definitive treatment without serious complication, a point mostly ignored in the included literature.

Timeliness of transport and definitive treatment is emphasized, and different time stamps and intervals are suggested as a quality measurement: first patient transport to transport of last immediate patient,Reference McCarthy, McClure and Heightman 74 and incident to last survivable patient in treatment facility.Reference Heightman 63 The benchmark time requirement is mostly expressed as “as soon as possible,”Reference Heightman 63 , 71 , Reference Wang, Ma and Hanson 105 but Gryth et al refer to “the golden hour.”Reference Gryth, Rådestad and Nilsson 60

Whereas most of these indicators are possible measures of effectiveness of the emergency response, Dudfield calls for evaluation of efficiency.Reference Dudfield 53 Rüter et al also suggest evaluating whether the objectives for the operation in question were reached.Reference Rüter, Nilsson and Vikström 91

A different approach to evaluating the commanders could be to assess their decision-making skills, including their “ability to handle problems outside the standard plans or models.”Reference Barishansky and O'Connor 42 Flin and Arbuthnot find this difficult, but state “outcomes are not a clear guide to the competence of the officer performing the task.”Reference Flin and Arbuthnot 57 Rüter et al claim decisions could be evaluated as to whether they benefit victims and contribute to the aim of the operation.Reference Rüter, Nilsson and Vikström 91

Limitations

Most comprehensive reviews in the medical literature are of an aggregative nature, and are concerned with questions like what intervention is the most effective in the treatment of an illness. The aim of this qualitative, configurative synthesis was to describe the breath of the field of medical incident command in mass-casualty incidents. Careful considerations were done before deciding to include non-peer-reviewed literature and papers based on data from non-medical settings. This choice was based on the assumptions that practical experience, also from related contexts, would be of importance in building knowledge of how the prehospital medical response operation, as a part of a broader system, can and should be led. The material on which this study was based is therefore considerably less standardized than what is common for classical medical meta-analyses. If this was meant to be such a study, the amount of eligible texts would have been negligible, possibly also giving results that were less valid for practical purposes. On the other hand, there is no reason to believe that the majority of non-peer-reviewed literature is to be found indexed in the databases used. A great amount of such texts appears in non-indexed journals or administrative documents. This fact introduces an unavoidable bias in the included literature. Previously published guidelines for evaluation and research on health disaster management do not appear to be used commonly (eg, for standardizing terminology and methods).Reference Sundnes and Birnbaum 108

A general observation was that the peer-reviewed papers presented a variety of scientific angles, while the non-peer-reviewed papers were more homogenous. A discourse analysis of the literature could be of interest to illuminate whether most practitioners actually share the same experiences, or if there is an informal standard to what one feels obliged to write about the subject. Such an analysis was beyond the scope of this review. It was, however, interesting to note that there were scarcely any quality differences between peer-reviewed and non-peer-reviewed case stories.

Due to linguistic challenges, this study is restricted to texts published in Scandinavian languages or English. This favors material from North and Western Europe and North America. Papers from other parts of the world may show a different picture. However, judged from the included texts based on experiences from other health systems, there are no systematic differences related to location.

Conclusion

Seen from all points of view, an efficient ICS has to rely upon competent and experienced commanders. Based on the included data, analysis gives no reason to believe that the competence and experience of the commanders can be significantly compensated by plans and procedures, or even by guidance from superior organizational elements such as coordination centers.

The study neither finds that a certain system, structure, or specific set of plans are better than others, nor can it conclude what system prerequisites are necessary or sufficient for an efficient incident management.

Nevertheless, it is clear that commanders need to be sure about their authority, responsibility, and the functional demands posed upon them. The description of such elements is a sensible part of a plan that can be expected to work. System and plans thus seem to be important for defining the role of the commanders and the other actors on scene, more than giving them detailed instructions on how to execute their work. These findings draw the attention in the same direction as previously described by Smith.Reference Smith 11 The study cannot conclude whether command and control strategies are more or less efficient than coordination strategies. Perhaps this may be because these two strategies are clearly differentiated in theory, but not so easily distinguished in practice. The great diversity related to terminology and methods calls upon continued efforts to standardize research in this field.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contribution of Marie Isachsen, at the Medical Library of Oslo University Hospital, and Inger Gåsemyr, at the University Library in Stavanger, in constructing and performing the database search, and Lena Gran in developing illustrations.

Supplementary materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S1049023x15000035