Introduction

Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) is a global public health problemReference Mozaffarian, Benjamin and Go1 with unfavorable resuscitation outcomes.Reference Okubo, Kiyohara and Iwami2,Reference Beck, Bray and Cameron3 Survival from OHCA largely depends on a set of sequentially coordinated, recursive interventions known as the life chain. Early bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation (BCPR) provision before Emergency Medical Services (EMS) arrival can increase the opportunity of survival from OHCA.Reference Stiell, Nichol and Wells4-Reference Wissenberg, Lippert and Folke6 However, despite large-scale community training programs, BCPR rates in cases of witnessed arrest have been persistently low.Reference Ro, Song and Do Shin7

Dispatcher-assisted bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation (DA-BCPR), which is implemented to augment the positive effect of BCPR and may improve outcomes of patients with OHCA, refers to emergency medical dispatchers or other emergency medical system staff issuing cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) instructions to a bystander via telephone when OHCA has likely occurred. Simulation studies showed that with instructions from a dispatcher, bystanders without any experience of CPR training acted with comparable CPR quality to previously trained persons.Reference Kellermann, Hackman and Somes8 In addition, very few serious adverse consequences of these DA-BCPR programs have been reported to date.Reference White, Rogers and Bloomingdale9

However, previous articles comparing outcomes in systems with DA-BCPR were inconsistent and were limited by several methodological problems, such as small sample size or insufficient control of covariates. Besides, previous systemic reviews revealed that there was limited evidence supporting the survival benefit of DA-BCPR instructions. Studies comparing survival outcomes when CPR was provided with or without the assistance of DA-BCPR instructions lacked the statistical power to draw significant conclusions.Reference Bohm, Vaillancourt and Charette10 However, dispatcher training, continuous quality control, and other DA-BCPR improvement projects were promising in improving operational links of DA-BCPR in recent years.Reference Tsunoyama, Nakahara and Yoshida11-Reference Huang, Fan and Chien13 It is imperative to summarize the existing studies about the outcome of DA-BCPR again. A systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to summarize current research results on the survival and neurological outcomes of DA-BCPR was conducted.

Material and Methods

This meta-analysis was performed according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (version 5.1.0) and presented based on Preferred Reporting Items for Systemic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Guidelines (Appendix 1; available online only).Reference David, Larissa and Mike14 The protocol for this article is available in PROSPERO (CRD42019119277).

Data Source and Search Strategy

PubMed (National Center for Biotechnology Information, National Institutes of Health; Bethesda, Maryland USA), Embase (Elsevier; Amsterdam, Netherlands), and the Cochrane Library (The Cochrane Collaboration; London, United Kingdom) were electronically searched for relevant citations using relevant text words and Medical Subject Headings by two independent researchers (Appendix 2; available online only). Moreover, magazines and meeting abstracts in the hospital library also were manually retrieved. There were no language or geographic restrictions and all searched studies were published from the date of inception to December 2018. No document restrictions and no methodology filters were applied. The search was limited to humans.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Trials were selected based on the following inclusion criteria: (1) trials enrolling adults or children suffering OHCA; (2) the intervention was DA-BCPR; (3) bystanders in comparison group did not receive dispatcher CPR instructions; (4) studies providing BCPR rate, survival rate, or neurological outcomes of patients; and (5) randomized controlled trials or observational trials. Exclusion criteria were: (1) enrolled samples were all OHCA patients with BCPR; (2) the intervention was a bundle of CPR programs, including DA-BCPR; and (3) simulated patients and humans.

Assessment of Methodological Quality

Although preferable, a randomized controlled trial could not have been possible, because withholding a potentially life-saving intervention would be considered unethical. In this review, all included articles were non-randomized. As a result, the Methodological Index for Non-Randomized Studies (MINORS)Reference Slim, Nini and Forestier15 was applied to further access the quality of each study by two reviewers independently. This validated index involves 12 items, the first eight items specifically designed for non-comparative studies and the remaining four items applied to comparative studies. Items are scored as zero (not reported), one (reported but inadequate), and two (reported and adequate). The maximum ideal score for non-comparative studies is 16, and for comparative studies, it is 24.

Data Extraction

Included articles were examined in-depth and key data were extracted using a standardized electronic form: first author’s last name, year of publication, site of origin, enrolment period, witnessed cardiac arrest (CA), number of institution, patients’ age, the number of cases and controls, female rate, mean age, study design, etiology of CA, and follow-up duration. Survival to discharge was the primary outcome variable; if data of survival to hospital discharge were not available, 30-day survival was used as the primary outcome. Secondary outcomes were BCPR rate, return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) before admission, hospital admission, and cerebral performance category (CPC) at discharge (if not available, 30-day CPC applied). Once chest compression was operated, CPR initiated. The odds ratios (OR) of preceding outcomes and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were extracted, and if not available, numbers of dichotomous outcomes were extracted. Any disagreement in extracted data was settled by consultation, and a final consensus was reached on all items. For CPC categories, CPC 1 was defined as good cerebral performance and CPC 2 was defined as moderate cerebral disability; CPC 1-2 was deemed as good neurological recovery while CPC 3-5 was regarded as bad neurological recovery.

Statistical Synthesis and Analysis

Factors documented in at least three studies were entered into a meta-analysis. Odds ratio (OR) and 95% CI were calculated through the chi-square test by SPSS version 24.0 (IBM Corp.; Armonk, New York USA) for primary studies not reporting OR and 95% CI calculated by multivariate analysis. The adjusted data and unadjusted data were all included in the meta-analysis. Random-effect model was used to pool the data given the observational nature and the differences in settings and population of included studies, and the percentage of variability across the pooled estimates attributable to heterogeneity beyond chance was estimated using the I2 statistic and the P value (a P value of less than or equal to 0.1 for heterogeneity). If no adjusted OR and 95% CI were reported in the included studies, the pooled OR was calculated according to dichotomous data. Sensitivity analysis was performed by shearing-patching methods. Another sensitivity analysis was performed by synthesized only adjusted data. Publication bias was assessed by funnel plot when the number of trials reporting the outcomes was 10 or more. All meta-analyses were performed using STATA version 13.1 (Stata Corporation; College Station, Texas USA). All tests were two-tailed, and P <.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Studies Retrieved and Characteristics

The literature search yielded 1,126 articles, of which 58 were reviewed in full text. Of these, 45 studies were excluded because they did not fulfil inclusion criteria. The flowchart of systemic review was displayed in PRISMA Flow Diagram. These studies and reasons for their exclusion are listed in the Supplemental Material 1 (available online only). At last, 13 studies (235,550 patients [DA-BCPR group 97,925 and non-DA-BCPR group 137,625]) met inclusion criteria.Reference Fukushima, Imanishi and Iwami16-Reference Akahane, Ogawa and Tanabe28 The flow chart of this systemic review is shown in Figure 1. However, no randomized controlled studies were identified. These observational studies included three before-after studies, nine retrospective studies, and one prospective cohort study. These studies were conducted in Japan (6; 46.2%), American (2; 15.4%), Finland (2; 15.4%), Sweden (1; 7.7%), Canada (1; 7.7%), and Korea (1; 7.7%). The duration of follow-up ranged from the process of DA-BCPR to one year following CA. Two studiesReference Goto, Maeda and Goto27,Reference Akahane, Ogawa and Tanabe28 explored the impact of DA-BCPR on outcomes in children, while the rest invested the impact of DA-BCPR on outcomes in adults (or mostly adults). All trial results were published from 1976 through 2012. Sample size ranged from 135 to 173,565. Patients in seven studies were all witnessed OHCA. These study characteristics are shown in Table 1a and Table 1b. Their MINORS ranged 13-20 (Supplemental Material 2; available online only).

Figure 1. Flowchart of Systemic Review.

Table 1a. Characteristics of Included Studies

Abbreviations: CA, cardiac arrest; MINORS, Methodological Index for Non-Randomized Studies; NR, not reported.

a Samples included in meta-analysis.

b Mean (standard deviation).

Table 1b. Characteristics of Included Studies

Abbreviations: CA, cardiac arrest; MINORS, Methodological Index for Non-Randomized Studies; NR, not reported.

a Samples included in meta-analysis.

b Mean (standard deviation).

c Median (interquartile range).

BCPR Rate and DA-BCPR

A significant difference in BCPR rate was found (OR = 5.84; 95% CI, 4.58-7.46; P <.01) favoring 97,561 DA-BCPR to 137,217 non-DA-BCPR enrolled in 11 articles with substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 98.2%; P <.01; Figure 2). Sensitivity analysis including both shearing-patching methods and adjusted data were taken and indicated that this outcome was robust (Supplemental Material 3; available online only). Funnel plots showed that there was publication bias, and the publication bias was mostly due to substantial between-study heterogeneity (Supplemental Material 3).

Figure 2. Forest Plot of Studies Reporting BCPR Rate.

Survival Rate and DA-BCPR

A significant difference in ROSC before hospital admission was found (OR = 1.17; 95% CI, 1.06-1.29; P <.01) favoring 18,955 DA-BCPR to 29,254 non-DA-BCPR enrolled in seven articles with mild heterogeneity (I2 = 36.0%; P = .15; Figure 3). Sensitivity analysis of shearing-patching methods was taken and indicated that this outcome was robust (Supplemental Material 3).

Figure 3. Forest Plot of Studies Reporting ROSC before Hospital Admission.

No significant difference in hospital admission was found (OR = 1.09; 95% CI, 0.91-1.30; P = .36) between 2,830 DA-BCPR and 6,355 non-DA-BCPR enrolled in five articles with mild heterogeneity (I2 = 29.0%; P = .23; Figure 4). Sensitivity analysis of shearing-patching methods was taken and indicated that this outcome was not robust (Supplemental Material 3).

Figure 4. Forest Plot of Studies Reporting Hospital Admission.

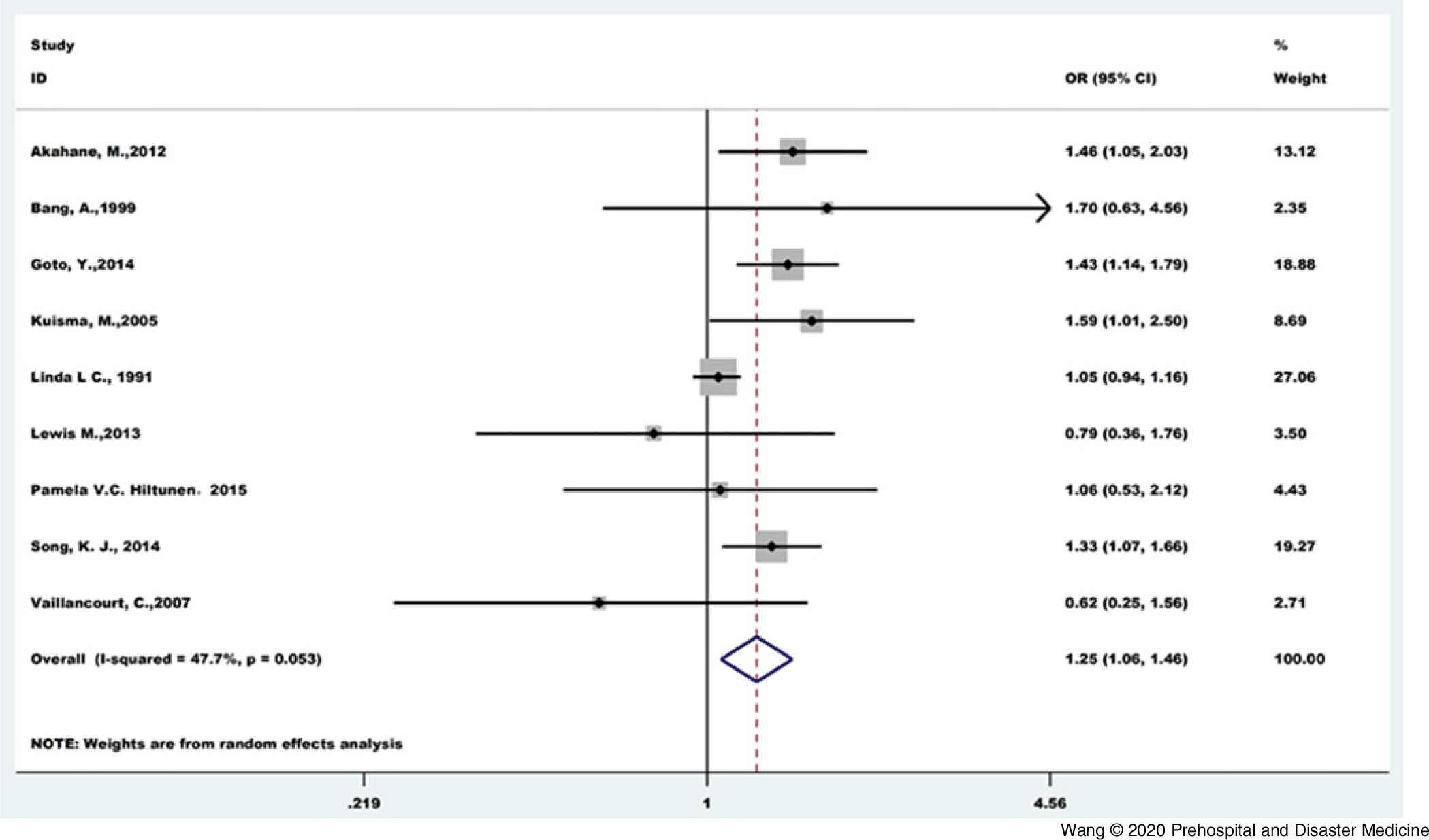

Overall discharge or 30-day survival rate tended to be higher in 11,298 DA-BCPR than 11,702 non-DA-BCPR (OR = 1.25; 95% CI, 1.06-1.46; P <.01), and moderate between-study heterogeneity was observed for this analysis (I2 = 47.7%; P = .05; Figure 5). Sensitivity analysis including both shearing-patching methods and adjusted data were taken and indicated that this outcome was robust (Supplemental Material 3).

Figure 5. Forest Plot of Studies Reporting Survival Rate.

Neurological Outcomes and DA-BCPR

A significant difference in neurological outcome was found (OR = 1.24; 95% CI, 1.04-1.48; P = .01) favoring 21,551 DA-BCPR to 31,412 non-DA-BCPR enrolled in six articles with mild heterogeneity (I2 = 30.9%; P = .19; Figure 6). Sensitivity analysis including both shearing-patching methods and adjusted data were taken and indicated that this outcome was robust (Supplemental Material 3).

Figure 6. Forest Plot of Studies Reporting CPC1-2 Rate.

Discussion

In view of the previous studies, the impact of DA-BCPR on survival and neurological outcomes with OHCA may be inconsistent. This systemic review and meta-analysis found DA-BCPR enhanced the provision of BCPR and improved the survival and neurological outcomes in pediatric and adult OHCAs. Survival to hospital admissions have shown trends of improvement but have yet to achieve statistical significance. European Resuscitation Council Guidelines for Resuscitation noted that dispatchers should provide telephone-CPR instructions in all cases of suspected CA, unless a trained provider is already delivering CPR.Reference Perkins, Olasveengen and Maconochie29

Early detection, call for help, early access to emergency services, and promptly initiated CPR were very important and known as elements of the “chains of survival.”Reference Perkins, Olasveengen and Maconochie29-Reference Nakahara, Tomio and Ichikawa32 Previous studies showed that the survival rate decreased as CPR was delayed.Reference Larsen, Eisenberg, Cummins and Hallstrom33 Speedy BCPR is a key factor in improving survival from OHCA, offering a potential 50% decrease in mortality.Reference Herlitz, Bang and Gunnarsson34 Fifty-three percent of CAs were witnessed by a bystander; however, only 32% of victims actually received BCPR before arrival of EMS.Reference Sasson, Rogers, Dahl and Kellermann35 Because most OHCA events were witnessed, efforts to improve survival should focus on prompt delivery of interventions of known effectiveness by bystanders. This research demonstrated that DA-BCPR could improve the probability of BCPR. As the effectiveness of BCPR is time-dependent, DA-BCPR before EMS arrival should be encouraged. Though, 56% of CA patients in included studies still did not receive BCPR. Recognition of CA and prompt activation time on the part of emergency medical dispatch are key measures that have been associated with improved survival rates after OHCA.Reference Lewis, Stubbs and Eisenberg36. Vaillancourt, et al found that dispatchers had 65.9% sensitivity and 32.3% specificity for the recognition of OHCA.Reference Vaillancourt, Charette and Kasaboski37 An optimized protocol, which includes a dispatcher education and training program, monthly debriefing meetings, and continuous quality control, is promising as it improved the successful recognition of CA.Reference Huang, Fan and Chien13 The sensitivity of medical priority dispatch systems in detecting CA was 76.7% and the specificity was 99.2%.Reference Flynn, Archer, Morgans and Morgans38 A longer detection time interval from the call for ambulance to the detection of OHCA by the dispatcher in DA-BCPR showed significantly lower good neurological recovery in adult patients with witnessed OHCA. A 30 second delay in detection time interval was associated with a three percent decrease of a good CPC score.Reference Ko, Shin and Ro39 Given this situation, simplified DA-BCPR instructions have resulted in time reduction and greater compression depth, even though the hand position might be corrected frequently in the conventional instruction group.Reference Dias, Brown and Saini40 Delays in the delivery of dispatcher-assisted CPR chest compressions are common and are attributable to a mixture of dispatcher behavior and factors beyond the control of the dispatcher.Reference Lewis, Stubbs and Eisenberg41 Inability to move patients to a hard, flat surface is associated with a reduced rate of DA-BCPR and increased time to first compression.Reference Langlais, Panczyk and Sutter42 Even trained bystanders sometimes hesitate to start CPR and the dispatcher can also in these cases play an important role.Reference Swor, Khan and Domeier43 Some standardized protocols have the potential to help bystanders initiate CPR.Reference Stipulante, Tubes and El Fassi44 Instruction on chest-compression-only CPR; education on how to recognize OHCA with agonal breathing, emesis, and convulsion; recommendations for on-line or re-dialing instructions; and feedback from emergency physicians increased the incidence of telephone CPR and BCPR, and also decreased the incidence of failed DA-BCPR.Reference Tanaka, Taniguchi and Wato12 On-going training of medical dispatchers to ensure recognition of OHCA during emergency calls and provision of DA-BCPR instructions to the bystander was encouraged in the 2015 European Resuscitation Council Guidelines as a strategy for improving OHCA recognition and performance of high-quality BCPR.Reference Greif, Lockey and Conaghan45

As was shown in this study, DA-BCPR was able to improve the probability of ROSC before hospital admission and discharge or 30-day survival, as well as the neurological outcomes. The CPR performed before EMS arrival was associated with a 30-day survival rate after an OHCA that was more than twice as high as that associated with no CPR before EMS arrival.Reference Hasselqvist-Ax, Riva and Herlitz46 The quality of CPR and prolonged time interval from collapse to CPR have been suggested as possible causes for the limited survival effect of DA-BCPR, but the cause has not been determined.Reference Bohm, Vaillancourt and Charette10,Reference Harjanto, Na and Hao47,Reference Rea, Eisenberg, Culley and Becker48 Although a shorter delay from collapse to CPR,Reference Group17 the initiation of BCPR prior to the emergency call was not associated with an increase of ROSC or 30-day survival compared with DA-BCPR.Reference Viereck, Palsgaard Moller and Kjaer Ersboll49 Conventional CPR is a complex behavior; skill acquisition is difficult and skill retention has been shown to deteriorate rapidly with time following community resuscitation training programs for the lay public.Reference Chamberlain, Smith and Colquhoun50,Reference Madden51 Thus, DA-BCPR was originally intended to initiate CPR by bystanders with little or no training, but may be equally important for the large group of trained who panic and failed to start CPR.Reference Swor, Khan and Domeier43 Simulation studies suggest that bystanders without former CPR training who receive dispatcher-assisted instructions show comparable CPR skills to previously trained persons, although more time elapses before initiation of CPR for the untrained group.Reference Kellermann, Hackman and Somes52 The pre-arrival CPR instructions have been shown to increase the rate and depth of chest compression and improve the quality of BCPR, even in laypersons with previous CPR training.Reference Merchant, Abella and Abotsi53 It has been established that dispatcher assistance improves BCPR rates,Reference Bohm, Vaillancourt and Charette10,Reference Harjanto, Na and Hao47 which leads to better outcomes.Reference Wissenberg, Lippert and Folke54 Implementation of a standardized DA-BCPR protocol (such as medical priority dispatch and criteria-based dispatch) resulted in faster identification of CA, response team dispatching, and arrival at scene. These factors were associated with a trend to better survival.Reference Plodr, Truhlar and Krencikova55 Some measures were taken to improve the efficiency of DA-BCPR. Real-time smart-phone video conferencing calls between EMS personnel and physicians is feasible for patients with OHCA, and effective to improve the survival rate and cerebral function recovery rate.Reference Lee and Park56 A feedback CPR program with professional recording and feedback of CPR process was associated with good neurological recovery and survival to discharge.Reference Park, Shin and Ro57

Limitations

However, several limitations should be acknowledged. Firstly, there is substantial heterogeneity among included articles for some outcomes. Although 2015 international consensus recommend that dispatchers provide chest-compression-only CPR instructions to callers for adults with suspected OHCA,Reference Travers, Perkins and Berg58 the EMS of each country is different, and there were no uniform standardized dispatch tools, so the instructions provided by dispatchers are various. Besides, the quality of BCPR and arrest-to-CPR duration was not reported in most included articles, and it may be uneven. In all of the studies in this meta-analysis, no data were available whether the bystander had been trained in CPR or not, and it was unable to measure the quality of the BCPR. Secondly, the cases included in this article covered a long span of 35 years from 1976 through 2011. The protocol of DA-BCPR may have changed during this period. This may be another source of heterogeneity. Thirdly, all the articles included in this meta-analysis were not randomized controlled trials, which downgraded the quality of evidence. Fourthly, most included articles did not report the adjusted ORs of outcomes, so the ORs calculated by cross-tabs did not considered the confounding factors; for example, patients’ age and gender, chest-compression-only or chest compression and mouth-to-mouth ventilation, attempted defibrillation, and collapse-to-initiation time.

Conclusions

This systemic review and meta-analysis provide evidence suggesting that DA-BCPR plays an important role for OHCA as a critical section in the life chain. It is effective in improving the BCPR rate, ROSC before hospital admission, discharge or 30-day survival, and neurological outcome. Optimized standardized dispatch tools and DA-BCPR quality improvement should be amended to achieve better outcomes.

Conflicts of interest

none

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049023X20000588