Introduction

In recent years, there have been many calls for increased accountability to populations affected by conflict and disaster.Reference Kirsch, Siddiqui, Perrin, Robinson, Sauer and Doocy 1 Concern has been raised regarding an erosion in trust in humanitarian agencies,Reference Jayasinghe 2 which have increased expenditures without necessarily improving performance. 3 Experts in the humanitarian sector have identified accountability as a top priority for the humanitarian sector,Reference Foran, Greenough and Thow 4 and advocated for improved coordinationReference Burkle, Redmond and McArdle 5 and collaborationReference Miles, Stevens, Erickson and Loke 6 in humanitarian responses. Efforts have been made to prevent corruption,Reference Maxwell, Bailey, Harvey, Walker, Sharbatke-Church and Savage 7 register foreign medical teams,Reference Redmond, O'Dempsey and Taithe 8 increase participation of affected populations,Reference Miller, Stolz and Ferris 9 and professionalize the field.Reference Walker, Hein, Russ, Bertleff and Caspersz 10

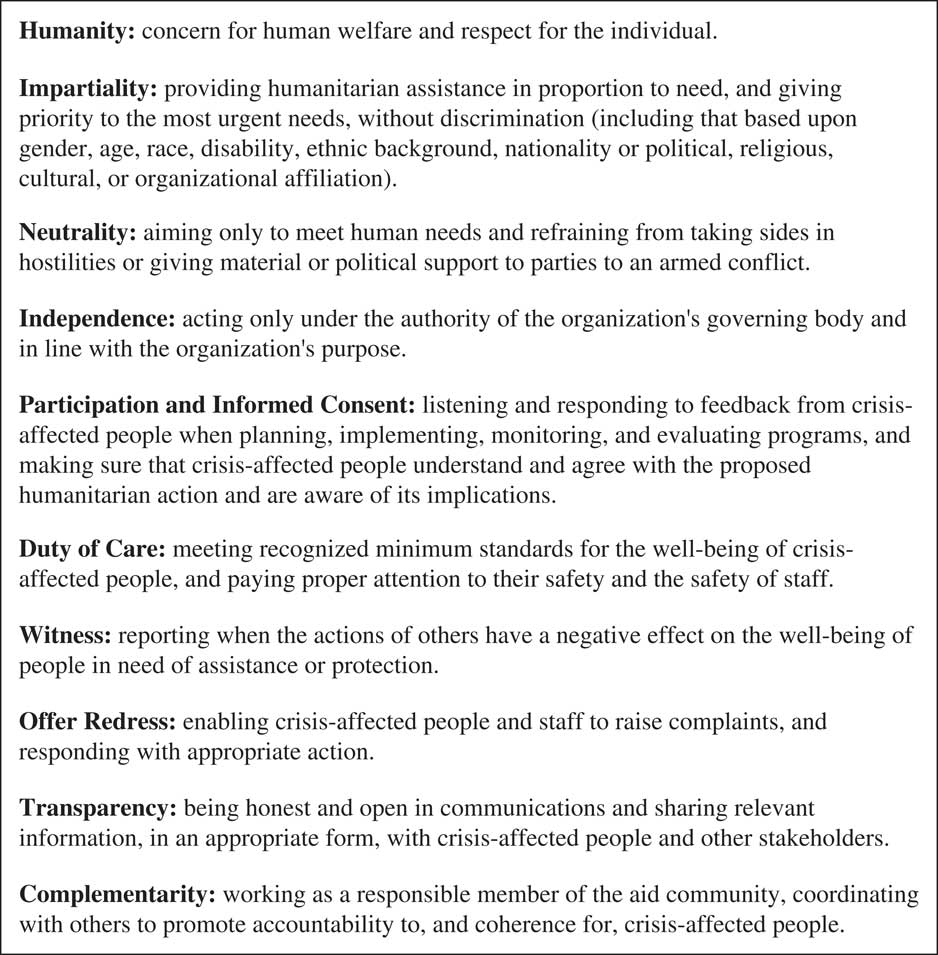

This current drive for accountability was born out of the troubled international response to the Rwandan Genocide of 1994.Reference Dabelstein 11 One of the key conclusions of the subsequent United Nations investigation was that the international humanitarian system needed an accrediting body. 12 In 2003, the Humanitarian Accountability Partnership International (HAP, Geneva, Switzerland) was created to fill this role. Rather than establishing a mandatory system of external regulation, as is common in other sectors, HAP was established as a voluntary, self-regulatory agency for humanitarian organizations,Reference Lloyd and Casas 13 with a focus on quality, in addition to accountability.Reference Hilhorst 14 The HAP promotes a set of core principles upon which its standard is built (Figure 1). By making HAP membership and certification optional, the humanitarian sector favored a soft launch, avoiding potential backlash against the initiative, but allowing for the possibility that a substantial portion of humanitarian organizations would not join in a timely fashion.

Figure 1 The HAP Standard Principles Abbreviations: HAP, Humanitarian Accountability Partnership.

After ten years of growth and implementation of HAP, it is important to assess the progress of uptake of membership by humanitarian organizations. No alternative universal and mandatory accrediting body has emerged. This study describes the growth of HAP membership from 2003 through 2012, measured in terms of both number of organizations and total annual budgets. This analysis was conducted to measure progress toward the goal of an accreditation system laid out in the 1999 Rwanda Report. 12 The hypothesis for this study was that HAP membership has grown substantially since inception, both in terms of number of member organizations and annual budgets of member organizations, but that near universal membership has not yet been achieved.

Methods

Data Sources

The list of organizations that were members of HAP for each year 2003-2011 were retrieved from the HAP annual reports for these years. 15 The 2012 HAP membership was obtained from the HAP website. The annual expenditures of the member organizations were obtained from their organizational websites and most recent available annual reports, which were in general from 2010. Those nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) for which no budget was publicly available were first contacted via email, then telephone. The few NGOs whose budgets could not be obtained via the above methods all fell into tier five in the State of the Humanitarian System report, corresponding to annual budgets of less than US $10 million.Reference Taylor, Stoddard and Harmer 16 These organizations were therefore assigned an estimated budget of US $10 million, erring on the side of overestimation of uptake. This rounding likely did not have a significant impact on the calculated proportions, given that the total estimated global expenditure was US $7.4 billion for 2012.

The estimated total number of humanitarian organizations worldwide and the total estimated humanitarian expenditures worldwide were obtained from the 2012 State of the Humanitarian System report.Reference Taylor, Stoddard and Harmer 16

Analysis

The total number of organizations that were members of HAP was tallied for each year, 2003 through 2012. These tallies were divided by the estimated total number of humanitarian organizations worldwide to produce the percent penetration of HAP in the sector for each year. The year 2012 was used as the baseline for estimated total number of humanitarian organizations (4,400 according to the 2012 State of the Humanitarian System report, though estimates vary).

The combined annual expenditures of organizations that were members of HAP were tallied for each year, 2003 through 2012. These cumulative expenditures were divided by the total estimated worldwide humanitarian expenditures obtained from the 2012 State of the Humanitarian System report.

The data obtained from the State of the Humanitarian System report are best available estimates and do not include confidence intervals. The calculations in this study based on these figures are therefore estimates as well; no confidence intervals could be calculated for data points on the resulting graphs.

The data collection did not involve human subject research and all data analyzed are publically available. Therefore, research did not meet criteria for submission to an institutional review board or ethics committee.

Results

The growth in membership in HAP from 2003 through 2012 is shown in Figure 2. In 2003, HAP had a total of eight members. By 2012, HAP reported 68 members. This amounts to a more than eight-fold increase in membership over ten years. Although this relative growth is impressive, the percentage of humanitarian organizations that were members of HAP remained quite low, still less than two percent by the end of 2012.

Figure 2 Growth in Number of Members in HAP International 2003-2012 Abbreviations: HAP, Humanitarian Accountability Partnership; NGO, nongovernmental organization.

The growth in total expenditures by HAP members from 2003 through 2012 is shown in Figure 3. Although the number of organizations that joined in 2003 was small, their budgets were, on average, large. This trend had continued over the subsequent nine years. By the end of 2012, although only 1.6% of humanitarian organizations were members of HAP, approximately 63% of global humanitarian expenditures were attributable to HAP member organizations.

Figure 3 Growth in Total Expenditures by Members of HAP International 2003-2012 Abbreviations: HAP, Humanitarian Accountability Partnership.

Humanitarian Accountability Partnership member organizations with budgets greater than US $100 million in 2012 are shown in Table 1.

Table 1 HAP Member Organizations with Budgets > US $100 Million in 2012

Abbreviations: HAP, Humanitarian Accountability Partnership; NGO, nongovernmental organization.

Discussion

These results portray a mixed picture with regards to progress toward a universal accrediting body for the humanitarian system. Humanitarian Accountability Partnership membership has grown steadily since inception, now including many of the largest, oldest, and most respected humanitarian organizations in the field. Now, HAP members account for more than half of all humanitarian expenditures, though the vast majority of existing organizations have not joined. The goal of avoiding backlash against an accrediting body has been achieved, as HAP has been generally well received since inception. Unfortunately, the risk of slow uptake is also now evident, especially amongst smaller organizations. These smaller organizations could be those that would benefit most from accreditation, as they are often younger, and they may have relatively little internal accountability programming or expertise. There are also notable large organizations that have not joined HAP, including Medecins Sans Frontiers (Geneva, Switzerland) and Catholic Relief Services (Baltimore, Maryland USA), both in the top five globally in terms of total annual expenditures.Reference Taylor, Stoddard and Harmer 16

One way to achieve near universal coverage of an accreditation system in the humanitarian sector is to make certification mandatory, not voluntary. Given the progress made by HAP over the past ten years, the humanitarian sector should now consider mandatory membership and certification, growing the mandate of HAP, and building on progress made. Improvements in accountability are critical to the future of the humanitarian sector, and HAP can play a key role in continued progress. At the same time, it is also important to promote efforts aimed at convergence of the various quality and accountability initiatives. These collaborations are gaining momentum, including the joint standards initiative, which has brought together HAP, People in Aid (London UK), and The Sphere Project (Geneva, Switzerland). 17

Limitations

All calculations and figures are based on best available estimates. The exact number of humanitarian organizations globally and exact total humanitarian expenditures are not known. The calculations reveal illustrative estimates only. Data from 2010 were used to estimate organization expenditures for the period 2005-2012; a similar growth rate between organizations and the sector overall during this period was assumed.

Conclusion

By 2012, ten years after inception of HAP International, less than two percent of humanitarian organizations were members, but the expenditures of these organizations accounted for over two-thirds of the global total. Although steady incremental progress was made over the first ten years, uptake was disproportionately seen among larger organizations. Efforts should be made to increase uptake among small to medium sized groups. The humanitarian sector should also now consider transitioning to a mandatory regulatory system to reach the stated goal of universal accreditation and oversight.