Introduction

Basic prehospital care at the site of a road traffic collision can be the difference between life and death for injured drivers, passengers, bicyclists, and pedestrians.Reference Chokotho, Mulwafu, Singini, Njalale, Maliwichi-Senganimalunje and Jacobsen 1 The faster an injured person receives first aid and then is transported safely to a hospital, the greater the likelihood of survival.Reference Peden, Surfield and Sleet 2 In high-income countries, emergency medical technicians (EMTs), paramedics, and clinical professionals with advanced life-saving skills are available to provide roadside trauma care.Reference Beuran, Paun and Gaspar 3 In low-income countries, trained first aid providers rarely are available and many trauma victims with survivable injuries die because they do not receive timely first aid and transfer to a hospital.Reference Beuran, Paun and Gaspar 3

Although sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) has the lowest number of vehicles per person of any world region, SSA has the highest rate of traffic-related fatalities per person.Reference Sasser, Varghese, Kellerman and Lormand 4 Within SSA, southern Africa has the highest road traffic fatality rates. 5 Malawi, a relatively small country (45,747 mi2) in southeastern Africa that is home to about 17.2 million residents and has a gross national income per person of only about $730 (in purchasing power parity international dollars) per year,Reference Chen 6 has one of the world’s highest rates of traffic-related fatalities per resident. 7 The World Health Organization (Geneva, Switzerland) has reported that Malawi has the highest road traffic mortality rate (35.0 per 100,000 in 2013) in the SSA region.Reference Chen 6 Road traumas are a common cause of hospital visits in Malawi,Reference Sivak and Schoettle 8 and they are the most common cause of adult injury-related deaths.Reference Chokotho, Mulwafu, Jacobsen, Pandit and Lavy 9 Malawi has no formal prehospital care system, no universal access emergency telephone number, and almost no ambulance service.Reference Sasser, Varghese, Kellerman and Lormand 4 Prehospital care is provided by a variety of responders: witnesses and bystanders who observe or respond to the crash, then provide initial care and call for help; official responders, such as police or firefighters; and drivers who transport injured people to hospitals.Reference Chokotho, Mulwafu, Singini, Njalale, Maliwichi-Senganimalunje and Jacobsen 1 However, these individuals usually have very little or no training in basic first aid. In 2015, the World Health Organization estimated that 5,700 Malawians die annually as a result of road traffic injuries, even though there is only about one motor vehicle in the country for every 40 residents.Reference Chasimpha, McLean and Chihana 10 The rate of road traffic fatalities per 10,000 vehicles remains similar to the rate in 1990, but the fatality rate per 100,000 population has increased significantly as the number of motor vehicles on the road has increased.Reference Chasimpha, McLean and Chihana 10 , 11

As the burden from road traffic injuries in Malawi and other SSA countries increases,Reference Olukoga 12 there is a critical need to improve access to community-based prehospital care. If more people in Malawi and other low-income countries are trained in first aid, the rate of preventable mortality and disability from road traffic collisions can be reduced substantially.Reference Beuran, Paun and Gaspar 3 This article presents the results of a qualitative study of prehospital care for road traffic injuries in Malawi that examined current practices for first response, emergency communication, and other aspects of prehospital trauma care and it explores the acceptability of various options for strengthening prehospital care.

Methods

A variety of qualitative data collection methods were used to gather data for this project. First, two focus group discussions, each approximately 90 minutes in duration, were held in April 2014. One group of key informants met in Karonga, a town in a rural district in northern Malawi, and included volunteers from an existing community-based participatory research panel. The other met in Blantyre, a large city in southern Malawi that serves as the country’s major commercial and financial center, with members of a community advisory group. Both study sites are located along the M1, the main north-south highway running the length of Malawi from Tanzania to Mozambique. Recruiting participants who had already established trust and rapport with one another and were comfortable speaking with health professionals allowed open discussion of possibly sensitive topics, such as expressions of opinions about political matters or disclosures of mental distress after witnessing serious injuries and fatalities.

Each focus group included 14 participants (eight females and six males), plus an interviewer and a note-taker. This number of participants is slightly larger than typical for a focus group, but turning away any volunteers from the purposively sampled community groups who had been victims of or responders to a road traffic collision might have diminished the rapport of the researchers with the participants. The participants ranged in age from 29 to 70 years, and they represented a diversity of occupations: businesspeople, religious leaders, health care workers, employees of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), laborers, and retirees. Of the 28 participants, 21 had responded to a traffic collision.

The guided discussions asked participants about their attitudes and perceptions related to who provides and who should provide roadside assistance, their beliefs about what actions are appropriate for various first responders to take at the site of a motor vehicle crash, their level of confidence in their own ability to provide roadside assistance, their impressions of the challenges encountered by first responders to collision sites, and their suggestions for improving prehospital care in Malawi. Transcripts from each session were generated, and those transcripts and the facilitators’ notes were examined for recurring themes and patterns and for the beliefs, attitudes, meanings, and explanations that consistently were expressed across both focus group discussions.Reference Lagarde 13

After the focus groups, the first response organizations identified by focus group members and the research team as being available to provide roadside assistance were contacted and one or more representatives asked to serve as a key informant. A checklist was used to identify the services, personnel, equipment, and other resources available for prehospital care from each of these entities. The checklist included specific items for communication gear, safety and personal protective equipment, extrication tools, immobilization and patient transfer equipment, and first aid supplies. Additional interviews were conducted with the national traffic police controller, regional traffic police commissioners, representatives of police and fire departments, regional directors for the National Road Safety Council (NRSC; Lilongwe, Malawi), a road traffic specialist, central hospital directors and district health officers from all along the M1 highway, clinicians, city health department representatives from Blantyre and Lilongwe, representatives from two telecommunications companies, and an official from the Malawi Communications Regulatory Authority (MACRA; Blantyre, Malawi).

This study was commissioned and approved by the Ministry of Health of Malawi (Lilongwe, Malawi) with the financial support of the World Bank (Washington, DC USA). The evaluation was designed to inform the Ministry’s efforts to reduce the burden of trauma along the North-South Corridor, a priority identified in Malawi’s National Non-Communicable Diseases Action Plan (2012–2016). All participants provided informed consent, with focus groups providing written documentation of consent and other interviewees providing verbal consent. The results of the focus group discussions and the other interviews were presented at a meeting with more than two dozen stakeholders in Lilongwe in October 2014, and additional insights were gathered at that time.

Results

Access to professional prehospital care in Malawi was extremely limited or nonexistent (Table 1). In major cities, fire departments may provide first aid to injured persons, but they lacked necessary medical equipment and were unable to transport trauma patients. Traffic police would respond to crash sites when called, but officers were not trained in first aid and rarely were able to provide patient transportation. Their primary roles were to redirect traffic around the crash site (such as by placing reflective triangles and flares in the road to slow oncoming traffic) and to conduct investigations for legal purposes. A few private organizations offered ambulance services, but these served only a small proportion of the population, and their personnel and equipment often arrived at the scene of a traffic collision only after patients had already been transported to hospitals by alternative means. Most ambulances were used for inter-hospital transport, not for initial transport to a hospital. For Malawians who did not live in major cities, only the police were formally available to respond to collisions. Thus, nearly all roadside first aid and other prehospital care following transportation-related traumas in Malawi was provided by community members.

Table 1 Major First Response Organizations Available in Malawi

Abbreviations: IV, intravenous; MASM, Medical Aid Society of Malawi; NGO, non-governmental organization.

Focus group participants identified rapid transportation to a hospital as the primary goal of first responders. While first aid was acknowledged as something that ought to be provided, most focus group participants lacked confidence in their ability to provide effective first aid. They were concerned about not knowing what to do, such as not knowing how to take a pulse. They worried that their attempts at first aid might harm victims rather than help them, perhaps by contaminating wounds or causing additional damage to fractured bones. Since no professional Emergency Medical Services are available for roadside assistance, they considered securing transportation to a hospital to be the most important contribution they could make at the site of a vehicle collision.

Focus group members felt that most community members had a desire to provide assistance to trauma victims and to attempt to save lives, especially when the collision caused serious injuries or when children were among the victims. The motivation to help was identified as umunthu—shared humanity. Lack of access to gloves, eyewear, and other personal protective equipment to minimize the risk of contracting HIV and other blood-borne infections was identified as a barrier to provision of first aid. Some focus group participants also expressed anxiety about the possible psychological trauma of witnessing a death. An additional concern was that some “helpers” would steal from victims. This was validated as a fear by nurses who reported an increasing proportion of trauma patients arriving at emergency centers missing their phones, watches, shoes, and other valuables.

Focus group participants emphasized the need for a trained leader to coordinate the response at the scene of a vehicle collision. Most bystanders were considered eager to help, but without a leader to assign tasks to them, many would act too slowly or spend time on low-priority responses. For example, some witnesses might not realize the importance of prioritizing care for a survivor with severe bleeding rather than attending to the body of a deceased victim. Others might attempt to chase after hit-and-run drivers rather than recording the number plate of the vehicle and then turning their attention to providing first aid to the injured. Some might attempt to pull casualties out of a damaged vehicle rather than waiting for equipment that might help with safe extrication. Focus group members considered appropriate roles for bystanders to include moving injured people to a safe place, stopping bleeding by using clothes and other fabric as bandages, providing resuscitation of victims who were not breathing, splinting injured limbs with cut tree branches, loosening the clothes of victims and fanning them, searching victims for identification, placing leaves or other warning indicators in the road to alert oncoming traffic to slow down, and contacting the police.

Communicating with police or other emergency service providers after a vehicle collision was deemed a major challenge by focus group participants. Most participants were not aware of the existence of emergency telephone numbers (such as *997, which is available only in some areas of the country and only works when the caller has a mobile phone plan with one of several telecommunications companies operating in Malawi), and others reported that those numbers did not work when they were dialed. A lack of telephones was reported to cause significant delays in contacting traffic police since a witness typically would need to locate a chief, a member of the neighborhood watch, or a community police member who could call for traffic police assistance. Witnesses reported sometimes needing to walk a far distance from the crash site to reach a police station and request help. Bystanders often resorted to flagging down a passing vehicle to ask for help, or collecting funds to hire private transportation to take victims to a health care facility. Some focus group members reported fear associated with police who might aggressively interrogate witnesses at the scene of the crash and involve them in future legal proceedings related to the crash.

The key recommendations from the focus groups on how to improve roadside assistance included: providing community health education about how to respond to traffic crashes, including how to provide basic first aid; emphasizing the spirit of umunthu and empowering community members to confidently do their best to help at the scenes of collisions; training community members to take leadership roles as first responders and supplying them with essential first aid equipment; ensuring that a working toll free number is available for summoning traffic police and that community members who are trained to respond to motor vehicle collisions have access to a mobile phone; investing in the resources needed to allow faster response times by uniformed traffic police officers who are prepared with reflective gear and other road safety equipment; and establishing, where possible, professional emergency response and ambulance services (including both 4-wheel and 2-wheel ambulances).

The experts participating in the follow-up stakeholder meeting, who represented a diversity of governmental agencies, NGOs, and academic institutions, proposed a variety of complementary options for improving access to and quality of prehospital care. These included: expanding access to ambulance services and ensuring that their patients are offered appropriate protections through regulations; promoting health insurance that covers prehospital care and transportation; increasing access to paramedic training; confiscating the driving licenses of drivers who have been responsible for multiple crashes; improving the national injury surveillance system to track progress toward reducing the burden of traffic injuries; and establishing a formal trauma care system across the country that includes both prehospital and in-hospital care. All of the key challenges related to prehospital care in Malawi and the solutions proposed by participants are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2 Key Challenges Related to Prehospital Care in Malawi and the Solutions Proposed by Participants

Discussion

Malawi and many of its neighbors in SSA haves no formal prehospital care system; they need to establish formal Emergency Medical Services to reduce the burden of preventable mortality and disability caused by traffic collisions.Reference Lincoln and Guba 14 , Reference Adeloye 15 Although it would be ideal to have professional emergency medical personnel available to provide prehospital care at every road traffic collision, budgetary realities make this a distant goal in low-income countries like Malawi. In the meanwhile, there is an urgent need to expand the number of community members—including local leaders, police, and commercial drivers—who are trained as first responders in Malawi and other low- and middle-income countries.Reference Mock, Jurkovich, nii-Ammon-Kotei, Arreola-Risa and Maier 16 - Reference Pallavisarji, Gururaj and Girish 18

Even short first aid courses can yield significant improvements in roadside care. A one-day prehospital trauma care course for community leaders, police, and taxi drivers in Uganda was effective in preparing participants to stop bleeding and safely move injured people.Reference Pitt and Pusponegoro 19 A similar type of program likely would be successful in Malawi, and the focus group participants’ eagerness to receive such training suggests that it would not be difficult to recruit volunteer first responders. Key topics to include in the training session would include calling for help, securing the scene, evaluating breathing and restoring airways with simple maneuvers, stopping bleeding through direct pressure, preventing infections, and stabilizing and immobilizing fractures.Reference Beuran, Paun and Gaspar 3

It is important for these trained community members to become a recognized and valued part of the formal prehospital care system in the country. A model for this kind of community-based program was implemented near Cape Town, South Africa, where emergency first aid responders (EFARs) who completed a one-day course and passed an exam were certified and issued identification cards.Reference Jayaraman, Mabweijano and Lipnick 20 The EFARs were empowered to respond to emergencies in their community and to care for injured persons until an ambulance arrived. Active EFARs who participated in monthly training meetings were provided with low-cost, locally-sourced first aid supplies as well as additional training.Reference Jayaraman, Mabweijano and Lipnick 20 The program was highly successful in improving prehospital care in the community.Reference Jayaraman, Mabweijano and Lipnick 20

Mandating first aid training for drivers, especially for the commercial drivers who account for a sizeable proportion of all road miles driven in countries like Malawi, may be particularly effective because other drivers are often the first people not involved in a crash to encounter the victims. Several studies have shown that even short training sessions for drivers can improve responses. In Ghana, where the majority of injured people are driven to hospitals by bus and taxi drivers, a 6-hour basic first aid course significantly improved drivers’ provision of first aid to passengers.Reference Sun and Wallis 21 Other basic first aid courses for commercial drivers in Ghana, Nigeria, and Uganda also caused a significant increase in first aid knowledge and in willingness to provide aid to injured people.Reference Pitt and Pusponegoro 19 , Reference Mock, Tiska, Adu-Ampofo and Boakye 22 , Reference Sangowawa and Owoaje 23 Malawi requires drivers to complete a training course before they can apply for a driver’s license, and the national government could make first aid training from a certified institute a mandatory part of the driving curriculum completed prior to taking the licensing exam. Similar benefits from driver first aid training would apply across much of SSA, because in many countries, the majority of trauma victims are transported by commercial vehicles and few ambulances are available.Reference Sun and Wallis 21 , Reference Tiska, Adu-Ampofo, Boakye, Tuuli and Mock 24 , Reference Oluwadiya, Olakulehin and Olatoke 25

In addition to training more laypersons to be skilled first responders, there is a need to build up the infrastructure for prehospital care: establishing emergency telephone numbers that work for all communication service providers, expanding the availability of trained emergency personnel and first aid equipment, and improving access to and utilization of ambulances (including motorcycle ambulancesReference Solagberu, Ofoegbu, Abdur-Rahman, Adekanye, Udoffa and Taiwo 26 ). There are models for success in SSA that Malawi and other countries can follow. For example, Ghana now has more than 100 ambulances across all 10 regions of the country, and EMTs with at least one full year of training provide prehospital care nationwide.Reference Hofman, Dzimadzi, Lungu, Ratsma and Hussein 27 The ambulance service of Lagos, Nigeria safely transports thousands of trauma patients each year.Reference Martel, Oteng and Mould-Millman 28

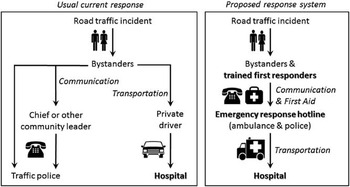

Improvements in prehospital care must be matched by progress in injury prevention and advances in hospital trauma care. Prevention of motor vehicle collisions (and reduction in the severity of injuries to drivers and passengers who are involved in a crash) could be facilitated in Malawi by enforcement of speed limits, seat-belt wearing, and laws related to alcohol consumption and driving, and by implementation of a national child restraint law.Reference Chasimpha, McLean and Chihana 10 Since 49% of all road fatalities in Malawi are pedestrians and another 17% are cyclists,Reference Chasimpha, McLean and Chihana 10 there also is a need to improve access to and use of sidewalks and to provide education on how bicycles and motor vehicles can share the road safely. Providing additional clinical training in best practices for in-hospital trauma care in resource-constrained settings could improve outcomes for trauma patients after they are transported to a health care facility.Reference Adewole, Fadeyibi and Kayode 29 In sum, there is a need to replace the current responses to road traffic injuries with a formal prehospital care system that includes trained first responders and an emergency response hotline for communicating with police and ambulance (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Current and Proposed Models for Prehospital Trauma Care for Road Traffic Injuries in Malawi.

Limitations

The focus group members who participated in this study cannot be considered representative of the general Malawian population. First, the focus group members were adults who are active in community groups and were therefore likely to overestimate the eagerness of volunteers to be trained in first aid and to prepare to lead responses to motor vehicle collisions. Second, the data for this study were collected only from two sites in the northern and southern regions of Malawi, not in the central region, and all participants lived along the main north-south highway rather than in remote areas. However, it is a strength that the focus group members and other stakeholders consulted during this process represented a diversity of sectors involved in emergency response, including agencies and organizations that have the authority and ability to implement the recommendations developed during this evaluation process.

Conclusions

The literature on prehospital care suggests that the recommendations from these Malawian focus groups are generalizable to other African settings. As a first step toward improving prehospital care for road traffic trauma casualties in Malawi, and other places where no formal emergency response system exists, it would be beneficial to create a formal network of community leaders, police, commercial drivers, and others lay volunteers who are trained in basic first aid and equipped to respond to crash sites to provide roadside care to trauma patients and prepare them for safe transport to hospitals. After these initial improvements are in place, Malawi can work toward establishing and strengthening a formal emergency response system.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all of the volunteers and stakeholders who participated in this analysis.