Introduction

Disasters necessitate a shift in the medical treatment paradigm from individual to population-based outcomes.Reference Lee, McLeod, Van Aarsen, Klingel, Franc and Peddle 1 This shift is reflected in the construction of mass-casualty incident (MCI) triage algorithms, whereby an attempt is made to ensure the most good is achieved for the greatest number of patients in resource-constrained environments.Reference Frykberg 2 Although the goal of accurate triage is to limit patient morbidity and mortality from over- and under-triage,Reference Lee, McLeod, Van Aarsen, Klingel, Franc and Peddle 1 the ability of triage tools to facilitate this outcome has yet to be demonstrated. Before this relationship can be investigated, however, one must show that triage algorithms have construct validity, which is the ability of a tool to assess patient acuity accurately.Reference Pesik, Keim and Iserson 3 , Reference Jenkins, McCarthy and Sauer 4

The construct validity of triage tools has been investigated previously. Garner et al.Reference Schultz 5 retrospectively applied triage categories to consecutive trauma patients and determined the accuracy to which critical injury was identified, while Kahn et al.Reference Garner, Lee, Harrison and Schultz 6 investigated the accuracy of field triage categorizations compared to outcome-based triage categories in a train crash MCI. Multiple paper-based and simulation MCI scenarios have been used to investigate whether triage algorithms can be employed to place patients accurately into predetermined, correct triage categories.Reference Kahn, Schultz, Miller and Anderson 7 - Reference Risavi, Terrell, Lee and Holsten 15 These studies have included many different triage algorithms as no tool has been shown to be definitively superior.Reference Pesik, Keim and Iserson 3 In an effort for consensus, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Atlanta, Georgia USA) produced the Sort, Assess, Life-saving intervention, Treatment/Transport (SALT) tool in 2008.Reference Jones, White and Tofil 16 The SALT tool has potential benefit as a triage tool since it is designed for both adult and pediatric populations, begins with global sorting to limit self-triage, expands the list of life-saving interventions (LSIs), and specifically distinguishes the “expectant” population.Reference Jones, White and Tofil 16 Recent studies have investigated the triage accuracy of SALT,Reference Schenker, Goldstein and Braun 9 , Reference Sapp, Brice, Myers and Hinchey 11 - Reference Deluhery, Lerner, Pirrallo and Schwartz 13 , Reference Risavi, Terrell, Lee and Holsten 15 but the large variations of results and the heterogeneous nature of studied triage officers suggest additional studies would help delineate the ability of the tool to identify patient acuity.

While validity studies are necessary for triage algorithms, continuing to develop strategies to optimize triage is also required. Accurate and timely triage is currently the best means for which to identify acutely ill patients and prioritize care. However, the disproportion between injured patients and available field triage officers during a MCI is often a barrier to timely triage. One strategy of rebalancing this disproportion may be to utilize additional first responders already on scene as triage officers, namely those with basic medical training such as fire services personnel. With additional first responders appropriately triaging patients in conjunction with Emergency Medical Services (EMS) providers, paramedics may be more able to concentrate on medical care, LSIs, and timely transport.

The objective of this study was to determine the accuracy, error patterns, and time to triage completion of EMS and fire trainees utilizing the SALT triage algorithm during MCI simulation. The null hypothesis of this study was that the determined accuracy, error patterns, and time to triage completion detailed above would be similar between groups, while the alternative hypothesis was that a difference between groups in any of these variables would be found.

Methods

Study Design

Second-year students in the primary care paramedic (PCP) and fire science (FS) programs at two separate community colleges around the London, Ontario (Canada) area were invited to participate in this prospective, observational cohort study. Neither PCP nor FS students had prior exposure to mass-casualty triage tools, including SALT. Primary care paramedic students were in the final year of training of a two-year paramedic diploma program, whereas FS students had completed Level C cardiopulmonary resuscitation certification and received training comparable to the American Red Cross (Washington, DC USA) First Responder Course. The PCP and FS students participated in separate days in October 2014, each session beginning with a 30-minute didactic presentation on the SALT triage tool describing its background, triage categories, and step-wise application with example triage code assignments. Following the didactic session, participants were given a standardized debriefing regarding the simulation exercise. Details of victim number, acuity, and type of incident were withheld. The simulation depicted a four-car motor vehicle collision producing eight victims. Each victim case was designed independently by an emergency medicine physician (CL) and subsequently reviewed by a disaster medicine expert (MP) who assigned the “gold-standard” triage category for each patient. There was complete agreement between the intended triage category from the case designer and subsequent gold-standard triage categorization assigned by the disaster medicine expert. The victim composition determined a priori included one “dead,” one “expectant,” two “immediate,” one “delayed,” and three “minimal” cases. Each victim was played by a volunteer actor given standardized moulage and coaching depending on their predetermined injuries. Along with standardized moulage and acting, victims had a Patient Summary Card (Figure 1) appended to their person detailing all physical exam findings that were reasonably available and required for accurate application of the SALT algorithm. The only materials available to study participants were triage cards for labeling victims among SALT acuity categories. Each participant progressed through the simulation independently along with two research staff who recorded time to triage completion and triage categorization. The research staff only interacted with the participants to give results of LSI, if simulated. Recorded time started once a participant entered the scenario, with time to triage of the first victim case recorded once a triage card was placed on a patient. Interval time between moving from one victim to placing down a triage card for the next victim was the time to triage for all subsequent cases. Written, informed consent was obtained from each trainee and participation was voluntary. The study protocol was approved by the Health Sciences Research Ethics Board at Western University (London, Ontario, Canada).

Figure 1 Sample Patient Summary Card. Abbreviation: GCS, Glasgow Coma Scale.

Outcome Measures

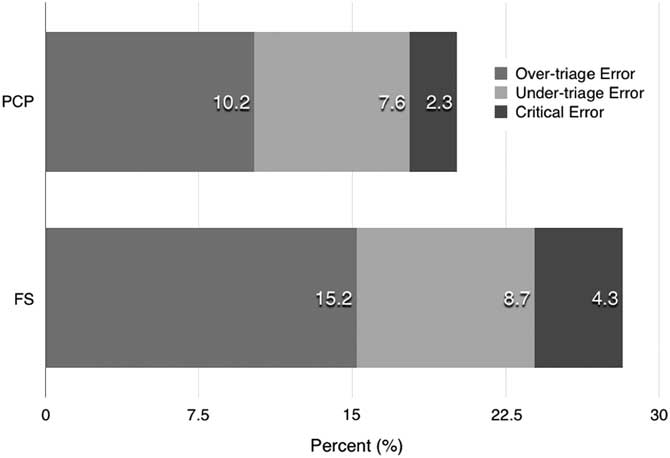

The primary objective of this study was to evaluate the ability of PCP and FS students to apply the SALT triage algorithm accurately during mass-casualty simulation. Secondary objectives were to compare triage error patterns and time to triage completion between groups. Triage error was defined categorically between over-triage, under-triage, and critical errors (Figure 2). Over-triage occurred when a patient was placed into a triage category necessitating higher priority treatment or transport than actually was required. While placing a patient into a triage category requiring lower priority treatment or transport than actually necessary incurred under-triage error. Critical errors were defined as triage error likely to incur irrevocable patient morbidity or mortality, which was most likely to occur when victims were placed erroneously into either “dead” or “expectant” categories. Placement into either of these triage categories drastically changed victim reassessment priority and thus had the potential to carry more significant morbidity and possible mortality.

Figure 2 Error Table.

Data Analysis

Data were entered directly into a study specific Microsoft Excel database (Microsoft Corporation; Redmond, Washington USA). Descriptive statistics were summarized using means and standard deviations or proportional differences within 95% confidence intervals. General linear models with repeated measures were used where appropriate and chi square tests were used to compare the proportion of errors made amongst responders. All analyses were performed using SPSS 21.0 (IBM Corporation; Somers, New York USA).

Results

Thirty-eight out of a possible 38 PCP and 29 of 36 FS students participated in the simulation. Overall triage accuracy was 79.9% for PCP and 72.0% for FS students (∆ 7.9%; 95% CI, 1.2-14.7; Figure 3). No significant difference was found between the groups regarding types of triage errors. Over-triage, under-triage, and critical errors occurred in 10.2%, 7.6%, and 2.3% of PCP triage assignments, respectively. Fire science students had a similar pattern with 15.2% over-triaged, 8.7% under-triaged, and 4.3% critical errors (Figure 4). The median [IQR] time to triage completion for PCP and FS students were 142.1 [52.6] seconds and 159.0 [40.5] seconds, respectively (P=.19; Mann-Whitney Test; Figure 5). Triage accuracy was below average in similar victim cases for both groups. Victim Cases 2, 6, and 8 were all triaged below the overall triage accuracy of the respective first responder cohorts, that is, less than 79.9% for PCP and 72% for FS (Table 1). Additionally, FS students had statistically lower triage accuracy in victim Cases 4, 5, and 7 in comparison to PCPs. There was no statistical difference in the triage time to completion between groups for individual victim cases.

Figure 3 Triage Accuracy. Abbreviations: FS, fire science; PCP, primary care paramedic.

Figure 4 Triage Errors. Abbreviations: FS, fire science; PCP, primary care paramedic.

Figure 5 Time to triage completion. Abbreviations: FS, fire science; PCP, primary care paramedic.

Table 1 Case-specific Triage Accuracy and Time

Abbreviations: FS, fire science; PCP, primary care paramedic.

Discussion

This study demonstrated that PCPs were able to perform SALT triage with greater accuracy than FS students during MCI simulation. Although a statistical difference in triage accuracy was found, it remains uncertain whether this translates into a clinical difference. Triage error was similar between groups, as was time to triage completion, suggesting that depending on resource availability and further training, fire services may be considered for MCI triage in conjunction with EMS providers.

The triage accuracy found in this study by both PCP and FS groups is in keeping with previous literature. Disaster simulation-based studies have been conducted using the Simple Triage and Rapid Treatment (START), JumpSTART, and SALT algorithms.Reference Risavi, Salen, Heller and Arcona 8 , Reference Schenker, Goldstein and Braun 9 , Reference Sapp, Brice, Myers and Hinchey 11 - Reference Deluhery, Lerner, Pirrallo and Schwartz 13 , Reference Risavi, Terrell, Lee and Holsten 15 , Reference Lerner, Schwartz and Coule 17 A triage accuracy of 78% for EMS providers using START was reported during a train collision disaster drillReference Risavi, Salen, Heller and Arcona 8 and 81% for a smaller study involving emergency medicine residents.Reference Lerner, Schwartz and Coule 17 JumpSTART, the pediatric version of the START algorithm, and SALT were studied recently by Jones et al.Reference Risavi, Terrell, Lee and Holsten 15 in a simulated pediatric disaster scenario where paramedics achieved a triage accuracy of 66% for both algorithms. Three studies involving SALT disaster simulations, each with either EMS students or staff, have achieved triage accuracies ranging from 70%-81%.Reference Schenker, Goldstein and Braun 9 , Reference Sapp, Brice, Myers and Hinchey 11 , Reference Deluhery, Lerner, Pirrallo and Schwartz 13 In comparison, the triage accuracy scores for PCP and FS in this present study were 79.9% and 72%, respectively, consistent with previous studies. These results suggest that fire services may be able to triage with suitable accuracy in a MCI setting.

There are limited studies reporting triage accuracy of first responder groups other than EMS agencies. Kilner et al.Reference Andreatta, Maslowski and Petty 18 found a triage accuracy of 81.4% for UK police officers who triaged a paper-based MCI scenario using the Triage Sieve algorithm. A recent abstract presentation revealed that police and fire service students were able to triage a paper-based MCI trauma scenario with 67.7% and 79.7% accuracy, respectively.Reference Kilner and Hall 19 Given the paucity of data informing the triage accuracy of other first responder groups, it is difficult to draw conclusions from the 72% triage accuracy for FS students in this present study. However, these data will serve as comparators for future research in the field.

When assessing triage accuracy, it is important to review over-triage, under-triage, and critical errors to determine where improvement gains can be made. In a paper-based study of first-year medical students using START, Sapp et al. reported an over-triage error of 17.8% compared to 12.6% under-triage.Reference Cone, Serra, Burns, MacMillan, Kurland and Van Gelder 10 A recent abstract presentation of a SALT triage study of PCP students revealed an error pattern of 10.5%, 2.8%, and 0.9% for over-, under-, and critical triage error, respectively.Reference Kilner and Hall 19 In terms of disaster simulation studies, opposing error patterns have been found. Two SALT studies have reported under-triage more frequently than over-triage,Reference Sapp, Brice, Myers and Hinchey 11 , Reference Deluhery, Lerner, Pirrallo and Schwartz 13 while adult and pediatric studies utilizing both SALT and START have revealed over-triage being more common.Reference Schenker, Goldstein and Braun 9 , Reference Risavi, Terrell, Lee and Holsten 15 In keeping with this pattern, a retrospective analysis of a true disaster scenario triaged using START revealed an over-triage rate of 49%, compared to under-triage of two percent.Reference Garner, Lee, Harrison and Schultz 6 In comparison, the frequency and pattern of triage errors reported in this present study are in keeping with the majority of previous studies for both PCP and FS, with over-triage being more frequent than under-triage, followed by critical error. The relative infrequency of critical errors and the overall similar pattern of triage error for FS students compared with previous EMS studies suggest that fire services may be considered for further study as MCI triage officers.

Apart from accurate triage, decision making in a MCI setting must also be prompt to optimize time to treatment and transport. Recent SALT triage accuracy studies have reported a wide range of times. Cone et al.Reference Schenker, Goldstein and Braun 9 found an average triage time for paramedic staff of 15 seconds per patient during live-action simulation, while a later virtual-reality simulation involving paramedic students from the same author averaged 51 seconds per patient.Reference Deluhery, Lerner, Pirrallo and Schwartz 13 Furthermore, a simulation run for civilian and military trainees during an Advanced Disaster Life Support course resulted in an average SALT triage time of 28 seconds per patient.Reference Sapp, Brice, Myers and Hinchey 11 The triage times noted in the Jones et al.Reference Risavi, Terrell, Lee and Holsten 15 study of Jump START and SALT triage algorithms were 26 and 34 seconds per patient, respectively. Given the heterogeneity of these studies in terms of population, scenarios, and utilized triage tool, it is difficult to compare the triage times reported in this present study. However, a triage time of 18 seconds per patient for PCP and 20 seconds per patient for FS provides support that fire services personnel may be able to triage in a timely manner comparable to EMS.

Looking at the individual victim cases within the MCI scenario, both groups had a similar pattern of performance, which further supports the assertion that fire services may be able to assist EMS in MCI triage (Table 1). Victim 2 consisted of an “expectant” patient with severe head injury and agonal breathing at four breaths per minute, who was often triaged as “dead.” Likely, a reminder to the strict definition of “dead” as no longer having any spontaneous respirations would ameliorate these critical errors. Victim 6 was a myocardial infarction case portrayed with acted chest pain in combination with moulage depicting a pale and diaphoretic victim. For both groups, this victim predominantly was under-triaged, possibly suggesting that SALT may be insensitive for acuity in non-traumatic illness, but is most likely explained by the relative inexperience of participants in this study in managing non-traumatic chest pain. Victim 8 described a patient with a mild blunt injury to the chest from air-bag deployment. This patient was commonly over-triaged to “delayed” although only minor injury existed. It is possible that this patient’s complaint of mild chest pain may have led student triage officers to be uncomfortable making a “minor injury only” determination, given that they could not entirely be assured of injury severity on cursory physical exam.

Fire science students had significantly worse triage accuracy in three scenarios compared to PCPs: Victims 4, 5, and 7. Victim 4 was a woman with superficial abrasions who was coached to be extremely anxious and distraught. Fire science students committed over-triage in 28% of triage encounters with Victim 4, which may be due to their lack of comfort in assessing for injury in emotionally distressed individuals. Victim 5 portrayed a man with a persistently bleeding open femur fracture, which was the only case designed to allow the students to consider LSIs, namely hemostasis maneuvers. Fire science students over-triaged this patient when they failed to employ a LSI, which would have controlled the bleeding and allowed the victim to be triaged as “delayed,” and under-triaged when they failed to recognize the injury severity. It is likely the difference in medical training between groups that played a role in determining whether LSIs were considered or performed. Similarly, a lack of familiarity by FS students with age-adjusted vital signs and pediatric trauma may have led to the 14% over-triage of Victim 7, a portrayed adolescent with no visible injuries. Although a triage officer is expected to practice only within their scope, the familiarity with different patient populations and certain LSIs may suggest that fire services inclusion in MCI triage be considered only in conjunction with EMS providers.

Limitations

This study is not without limitations. This was an observational study not powered to find a clinically meaningful difference in triage accuracy between groups of trainees. The number of participants in each group relatively was small, leading to a wide confidence interval around each point estimate of interest. Larger group numbers would have enabled a more precise estimate of the difference in triage accuracy and error pattern. Given that the study groups were comprised of students, the effect of field experience on MCI triage capability could not be captured in this study. However, because both groups had no prior experience with MCI triage, this study importantly demonstrates that a brief didactic session is sufficient to teach trainees to perform timely and accurate MCI triage using SALT. Whether this ability translates from a simulated MCI to a true, real-time disaster has yet to be determined. Although high-fidelity actors and moulage were provided, they are limited in their ability to mimic the chaos and urgency of a true disaster, which may affect triage accuracy. Furthermore, the majority of patient scenarios in this study were trauma cases, limiting the ability to generalize these results to other disaster scenarios.

Conclusions

Both PCP and FS students were able to learn and apply the SALT triage algorithm after brief didactic teaching. During MCI simulation, PCPs triaged with higher accuracy compared to their FS colleagues. Although there was a statistical difference between the triage accuracy of these two first responder groups, its magnitude was relatively small and the clinical importance of this difference likely is minimal. Furthermore, both triage errors and time to triage completion were similar between groups. These results suggest that fire services personnel can learn and apply SALT triage and could be considered for MCI triage depending on availability of prehospital resources and proper training.