Introduction

Pharmacists provide essential services in the aftermath of a disaster, supporting their community through continued supply of essential medications, devices, and services. 1 There has been recent interest in the roles that pharmacists may fulfil in a disaster aftermath and a call to see them more involved in disaster management and response. Reference Watson, Singleton, Tippett and Nissen2 While understanding pharmacists’ roles in disasters is necessary, it is also critical to understand how prepared pharmacists are to fulfil roles in a disaster. Currently, there is a lack of literature that attempts to measure and understand pharmacists’ preparedness for disasters. Reference McCourt, Singleton, Tippett and Nissen3

Most of the discourse in the literature around pharmacist preparedness focuses on narrative descriptions of pharmacists’ disaster experiences or the preparedness of pharmacies. Reference Henkel and Marvanova4-Reference Melin, Maldonado and López-Candales8 While these narratives are interesting, they do not provide an understanding of the disaster preparedness of pharmacists and may be subject to publication bias. For example, pharmacists who experienced a disaster but were not prepared or responded poorly are unlikely to share these experiences widely. Additionally, while literature on the preparedness of pharmacies may provide an understanding of physical preparedness in terms of disaster resources and plans, these studies fail to acknowledge that for a pharmacy to be open and operational in a disaster, there must be prepared pharmacists working in them. Reference Henkel and Marvanova4,Reference Ozeki and Ojima6,Reference Schumacher, Bonnabry and Widmer7 Having a prepared pharmacy does not necessarily make the workforce prepared.

There is no standardized way in which to measure disaster preparedness of health professionals. Reference Slepski9,Reference Gowing, Walker, Elmer and Cummings10 Much of the current literature on health professionals’ preparedness relies on individual’s perceptions of their preparedness to respond to disasters. Reference Lim, Lim and Vasu11-Reference Al Khalaileh, Bond, Beckstrand and Al-Talafha13 Other research attempts to use preparedness behaviors, such as planning for a disaster or attending an education session, as a marker for preparedness. Reference Corwin14,Reference Espina and Teng-Callega15 However, preparedness behaviors correlation with perceived preparedness has not been tested.

This research was designed to determine the following:

1. The factors that affect Australian pharmacists’ preparedness for disasters;

2. The factors that affect Australian pharmacists’ preparedness behaviors; and

3. The relationship between preparedness behaviors and preparedness in Australian pharmacists.

Methods

A 70-question online survey was developed using outcomes from previous research phases including a systematic literature review and interviews with pharmacists. The survey contained sixteen sections: (1) demographics, (2) disaster and preparedness context, (3) preparedness of self and colleagues, (4) attributes, (5) supplies, (6) planning, (7) behaviors, (8) knowledge, (9) response-efficacy, (10) self-efficacy, (11) response costs, (12) threat appraisal, (13) willingness to respond, (14) attribution of responsibility, (15) sense of community and professional responsibilities, and (16) trust of information sources. The survey was piloted on a group of pharmacists who provided feedback on readability of the survey and subsequent adjustments were made to the final survey. Most questions asked participants to rate their agreement or disagreement with statements on a five-point Likert Scale.

The survey was open from March 2018 through May 2018 and was advertised through the Society of Hospital Pharmacists Australia (Collingwood, Australia) weekly member updates, a research collaborative of hospital pharmacists, social media sites such as Facebook and Twitter, and was shared by pharmacy media outlets. The impact of self-selection to participate in the survey will be discussed in the Limitations section.

Individuals were invited to participate if they were registered pharmacists in Australia, regardless of their disaster experience, expertise, or place of work. Participants were excluded if they were pharmacy students, pharmacy technicians, or were not registered in Australia. Ethical clearance was obtained from Queensland University of Technology (Brisbane City, Queensland, Australia; Approval Number 1700000626).

Data Analysis

Data were imported from Key Survey (version 8.19; WorldApp; Braintree, Massachusetts USA) into Microsoft Excel (2016; Microsoft Corp.; Redmond, Washington USA), cleaned, and checked for consistency. Once cleaned, data were exported to IBM SPSS (version 25; IBM Corp.; Armonk, New York USA) for analysis. Exploratory Factor Analysis was used to create new variables for analysis. Tests comparing groups varied depending on the data ability to meet test assumptions. Multiple linear regression was used to create a model of preparedness behaviors and preparedness.

Variable Development

For data to be analyzed, several new variables had to be created from the survey. The variables “preparedness behavior” and “overall preparedness” are discussed here, and additional variables are discussed in Supplementary Material 1 (available online only).

Preparedness Behaviors

The variable “preparedness behaviors” was created by weighting and adding together each participant’s previous preparedness behaviors. Weighting was based on the type of activity and was developed to highlight the difference between “thinking” and “action.” For example, one point was awarded for previous consideration of how a disaster might affect their pharmacy, two points were awarded for information-seeking behavior, and three points were awarded to action behaviors such as participating in a disaster drill or training.

Overall Preparedness

Exploratory Factor Analysis is a statistical method used to reduce large sets of variables into a smaller set of summary variables that describe the underlying theoretical structure of the variables. Reference De Vaus16 Exploratory Factor Analysis was used to create the new variable “overall preparedness,” which consisted of participants’ assessments of their current education and training, clinical skills, experience, resources, knowledge, supports, and non-technical skills to be prepared for a disaster, and their perceived preparedness for a disaster.

Results

Demographic and Preparedness Context

The survey was undertaken by 123 participants and completed in its entirety by 88 participants. Full demographic information and disaster context of participants is available in Table 1.

Table 1. Demographic Information and Disaster Context

Factors Influencing Preparedness Behavior and Preparedness

The median preparedness behavior score of participants was 4.0 (IQR 1.00-9.75) of a possible 20.0 points. The median overall preparedness score was 14.9 (IQR 12.57-18.99). The lowest preparedness scores an individual could have was 5.72 and the highest score was 28.6.

Comparing Medians and Means

Appropriate statistical tests were used to determine if there were differences in the median or mean preparedness behavior or preparedness score between various groups (Table 2).

Table 2. Comparison of Preparedness Behavior and Preparedness Scores Between Groups

Note: Statistically significant values at P <.05 bolded.

Abbreviation: CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

^ Dunn’s pairwise comparison failed to demonstrate a significant difference.

Correlation Coefficients

Correlation measures were used to determine if preparedness behaviors and overall preparedness scores were affected by any continuous variables within the survey (Table 3). Preparedness behaviors and preparedness scores were moderately positively correlated with each other (rs = 0.561; P <.001).

Table 3. Correlation of Preparedness Behaviors and Preparedness Across Continuous Variables

Note: Statistically significant values at P < .05 bolded.

Multiple Linear Regression of Preparedness Behaviors

Thirty-four variables were entered into a stepwise multiple linear regression model with preparedness behavior score as the dependent variable. The final model had an R2 value of 0.711 (F(6, 48) = 19.723; P < .001; Table 4). This means that 71.1% of variation in preparedness behavior score was explained by the model.

Table 4. Multiple Linear Regression Model of Preparedness Behaviors

Multiple Linear Regression of Preparedness

Twenty-four variables were entered into a stepwise multiple linear regression model with preparedness score as the dependent variable. The final model had an R2 value of 0.86 (F(7, 50) = 43.785; P <.001; Table 5). This means that 86.0% of variation in preparedness score was explained by the model.

Table 5. Multiple Linear Regression Model of Preparedness Score

Concept Map of Preparedness and Preparedness Behaviors

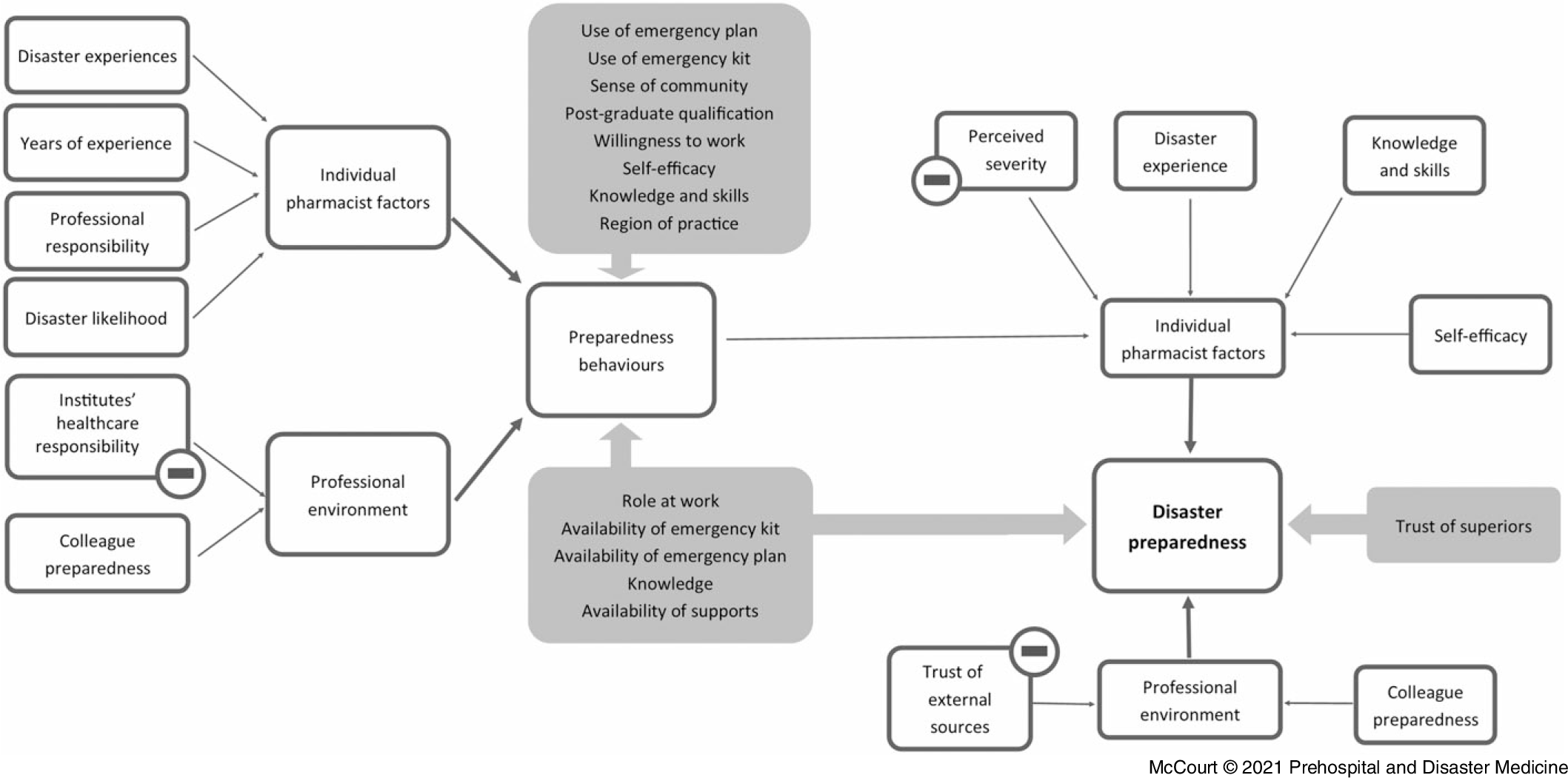

Based on the results of the bivariate analysis and multiple linear regression, a concept map of preparedness behaviors and disaster preparedness was developed (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Concept Map of Preparedness.

Discussion

Preparedness among participants was low-moderate and preparedness behaviors were low. The low preparedness behavior score of participants indicates low uptake of preparedness behaviors. This is not surprising, given that there are few resources or interventions available for pharmacists to improve their disaster preparedness in Australia. Reference McCourt, Nissen, Tippett and Singleton17,Reference McCourt, Nissen, Tippett and Singleton18 While professional organizations may provide advice to pharmacists in an impending disaster, there is no standardized education or training/drill available for Australian pharmacists to participate. Reference McCourt, Nissen, Tippett and Singleton17

While the preparedness behavior score and the preparedness score were moderately positively correlated, preparedness behavior does not fully explain an individual’s preparedness. This is interesting, as some research into preparedness utilize preparedness behaviors as a surrogate marker of how prepared an individual is. Reference Espina and Teng-Callega15 The research presented here indicates that an individual’s preparedness is made up of more than just their previous involvement in preparedness behaviors.

The concept map of preparedness generated from this research highlights several key messages for discussion. Firstly, almost all variables in the preparedness behavior and preparedness model have the potential to be modified through interventions such as education, training, or resource development. Arguably, disaster experience cannot be modified, however disaster drills or workshops which deliver an authentic disaster experience may contribute to improvements in preparedness. Reference Gowing, Walker, Elmer and Cummings10,Reference Crane, McCluskey, Johnson and Harbison19 All other variables can be modified with appropriate and targeted interventions, such as appropriately formulated education, training, disaster drills, or resources. Interventions must not only focus on skills and disaster knowledge, but on beliefs, expectations, and preparing as a health community rather than as individuals.

While these models provide areas for interventions to target, they also provide areas that require careful attention. For example, in the preparedness model, perceived severity of a disaster negatively affects preparedness. If an individual believes that a disaster affecting their area of practice is likely to cause severe damage, they will be less prepared. This aligns with other research and could occur if individuals believe that it is impossible to prepare for a disaster event due to the perceived severity. Reference Corwin14,Reference Becker, Aerts and Huitema20 To counterbalance this, interventions that encourage pharmacists to be aware of and prepare for more severe events could be provided.

Both the preparedness behavior and preparedness models indicate a delicate balance between internal and external beliefs, trust, and responsibility. For example, a sense of professional responsibility to prepare and respond to a disaster improves preparedness behaviors. However, ascribing responsibility of on-going community health to relief agencies, Australian Defence Force, local Emergency Services, and hospitals (health care responsibility of institutions) in a disaster appears to decrease preparedness behavior. It could be that these individuals do not see it as their role or responsibility to provide on-going health care to their community in a disaster and therefore do not believe they need to prepare themselves. The concept of ascription of responsibility relating to preparedness and preparedness behaviors has previously been explored in behavior theories related to laypeople. Reference Corwin14,Reference Lindell and Perry21,Reference Paton, Smith and Johnson22 This indicates that for participants to be motivated to undertake preparedness behaviors, they must feel professionally responsible to prepare and respond to a disaster; however, they must not place too much responsibility for on-going health care to other organizations or institutions such as relief agencies.

A critical finding of this work is that the preparedness of participants was influenced by internal and external factors. Most health preparedness literature either focuses on the preparedness of individual pharmacist or the facility in which pharmacists practice. Reference Henkel and Marvanova4-Reference Melin, Maldonado and López-Candales8,Reference Crane, McCluskey, Johnson and Harbison19 The findings of this research indicate rather than focusing on individuals or facilities, preparedness research and interventions should focus on the individual and the professional context in which they work.

Limitations

Of the 123 participants who started the survey, only 88 individuals completed the survey. The survey was long, as it explored a poorly researched area of preparedness, which likely contributed to the large numbers of individuals not completing the survey. Self-selection sampling techniques were used, which may have led to participants undertaking the survey being influenced by un-measurable biases, for example those who felt they were prepared for disasters or who had previously been involved in disasters may have been more likely to undertake the survey.

Hospital-based pharmacists from Queensland were over-represented in this survey. In Australia, only 20% of pharmacists work in the hospital setting; however in this survey, 60% of respondents reported working in the hospital setting. 23 Additionally, 20% of all registered pharmacists practice in Queensland; however in this survey, almost 50% of survey participants reported practicing in Queensland. 24 The gender and region of practice of participants in the survey was approximately representative of the pharmacy workforce. 24 It is probable that this over-representation of hospital pharmacists and pharmacists practicing in Queensland arose from the advertising methods employed to distribute the survey.

Future research phases will reduce the size of the survey, determine the appropriate sample size required for further research, use probability sampling techniques, and aim to distribute the survey across community and hospital pharmacies in each state of Australia. The work presented here may also be duplicated in other countries to determine if the models derived from this research reflect the preparedness of pharmacists practicing internationally.

Conclusion

Disaster preparedness of pharmacists may involve more than just knowledge, skills, and abilities. For study participants, their preparedness is an amalgamation of the resources available to them, their behavior, experiences, beliefs, knowledge, skills, and abilities as well as the preparedness of others in their professional work environment. For pharmacists in Australia, their ability to access resources and interventions which influence these factors remain limited. There is a critical need for relevant and accessible interventions designed to improve disaster preparedness among Australian pharmacists.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049023X21000133