Introduction

A coordinated and organized prehospital medical response to Multiple Casualty Events (MCE) is necessary to adequately care for the acutely and moderately injured. One of the major difficulties encountered in prehospital disaster modeling is the simultaneous occurrence of various prehospital activities in MCE such as triage, patient assessment, on-scene treatment, and transport to designated hospitals. Several articles have addressed prehospital time intervals for individual patients.Reference Blackwell and Kaufman1-Reference Gervin and Fischer12 In 1993, Spaite et al proposed a new time interval-based model for evaluating operational and patient care issues in Emergency Medical Service (EMS).Reference Spaite, Valenzuela and Meislin13 This model is currently used by several United States EMS systems. It divides the total prehospital time for individual patients into several successive and additive intervals (Figure 1).

Figure 1 (Color online) Prehospital time intervalsa

aadapted from Spaite et al, 1993Reference Spaite, Valenzuela and Meislin13

In spite of disaster medicine research efforts, a comprehensive prehospital response model for MCE is yet to be proposed.Reference Farmer and Carlton14-Reference Quarantelli18 Carr et al performed a meta-analysis of data reporting prehospital average time intervals for 155,179 trauma patients transported by ground ambulance and helicopter from 1990-2005 (Table 1).Reference Carr, Caplan and Pryor19

Table 1 Selected prehospital time intervalsFootnote a

a adapted from Carr et al, 2005Reference Carr, Caplan and Pryor19

In the literature, there is controversy regarding the impact of the prehospital time on patient outcome in trauma.Reference Newgard, Schmicker and Hedges20-Reference Cowley29 However, emergency medical systems still operate under the premise that the shorter the time is, the better the prehospital response.

The objective of this study was to identify the principal parameters necessary to quantitatively benchmark prehospital medical response in trauma-related MCE. The study focused on initiating treatment and completing the transport of critical (T1) and moderate (T2) patients, while taking into account the different capacities of the designated receiving hospitals.

Methods

A two-step approach was adopted in the methodology: a literature search, followed by prehospital system modeling. A literature review of MEDLINE, EMBASE, and CINAHL from 1950 through September 2010 was conducted to identify articles of interest using the following search terms individually and in various combinations: “ambulances,” “EMS,” “prehospital,” “capacity,” “multiple casualty incidents,” “disaster,” “disaster management,” and “disaster modeling.” Articles related to prehospital response in MCE were reviewed and manually searched for additional references. Special attention was given to trauma-related MCE. The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) triage categories [T1 (critical), T2 (moderate), T3 (minor), T4 (expectant)] were used in the modeling process.Reference de Boer30 Critical casualties in this model (T1) were considered to be equivalent to trauma casualties with a minimum Injury Severity Score of 16 and to the red category in the Simple Triage And Rapid Treatment (START) system. Moderate casualties in this model (T2) were considered to be equivalent to trauma casualties with an Injury Severity Score of less than 16 requiring admission to the hospital, and to the yellow category in the START system. Minor injuries (T3) and expectant (T4) were excluded from this model. One major assumption of this proposed model is that the time intervals for critical (T1) and moderate (T2) patients, from the occurrence of injury until the transfer of care to the receiving hospital, are consequential.

Results

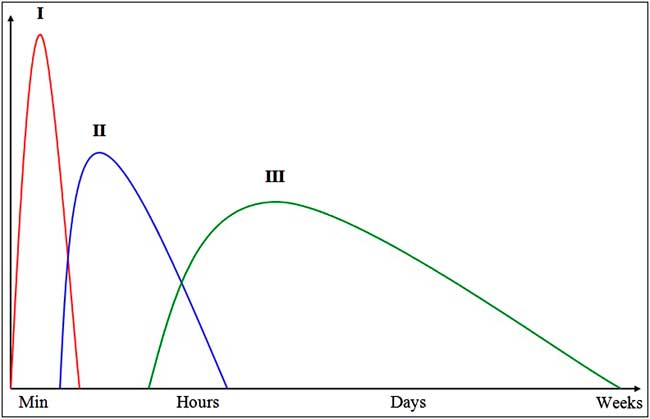

Important to the proposed model was Trunkey's concept of the tri-modal distribution of trauma fatalities.Reference Trunkey31 The first mode (immediate death, seconds to minutes after the impact) represents a group of casualties whose injuries are so severe that they cannot be saved, even with sophisticated medical interventions. This group is clearly not influenced by prehospital response. The second mode (early death, minutes to hours after the accident) is mostly due to respiratory and circulatory problems, both of which are potentially reversible with early prehospital care. The third mode (late death, days to weeks after the event) represents those who die days to weeks after the event due to injury or other complications. This mode is also affected by the prehospital medical response (Figure 2).

Figure 2 (Color online) Trunkey's tri-modal distribution of trauma fatalities

Maximum Time Allowed (MTA)

EMS systems worldwide operate under the premise that the care for T1 and T2 patients is consequential. The Maximum Time Allowed (MTA), from injury until definitive hospital care, has been debated in the trauma literature for the past few decades, mainly in regards to the exact time value of the MTA for critical and moderate patients.Reference Newgard, Schmicker and Hedges20-Reference Cowley29 MTA is defined as the maximum time from the occurrence of injury until transfer of care to the hospital, and was used in this study as one conceptual framework. The trauma literature provides two time references for injured critical (T1) and moderate (T2) patients. Historically, the “golden hour” had been considered by some trauma experts as the MTA for T1 (MTA1).Reference Newgard, Schmicker and Hedges20-Reference Cowley29 In addition, four to six hours, referred to by some as Friedrich's time, had been considered by others to be the MTA for T2 (MTA2).Reference de Boer and van Remmen32, Reference de Boer, Brismar and Eldar33 These two time references were used in the model for this study for conceptual illustration, acknowledging the major controversy surrounding their specific values.Reference Newgard, Schmicker and Hedges20-Reference Cowley29

Essential Parameters Modeled for the Prehospital Medical Response in MCE

Two inter-related time intervals, Injury to Hospital Interval (IHI) and Injury to Patient Contact Interval (IPCI), were identified and modeled as important for prehospital response to MCE. The IHI in this study's model is defined as the time interval from the occurrence of the injury of each T1 and T2 casualty to the completion of transfer of care to the designated hospital. The reason for the incorporation of the IHI in a MCE model relates to its easy interpretability. For example, the golden hour (1 hour) is the MTA for T1, and EMS should attempt its best during the prehospital response to have the IHI of all T1s fall within the limit of one hour.

The IPCI is defined as the time from injury occurrence until the patient is contacted by the treating and transporting team. This concept in MCE is a slight adaptation of Spaite's model for individual patients, where the IPCI replaces all other intervals concerning patient contact by the treating and transporting team. In MCE, ambulance teams first attend to triaged critical T1 patients for initiation of treatment and prompt transport. If the IPCI for a T1 patient is 20 minutes and MTA is one hour, the prehospital team has a maximum of 40 minutes to complete the remaining intervals (initial assessment, scene treatment, patient removal, transport, and delivery) in order to keep the IHI below the MTA of one hour. If the IPCI has already exceeded the one hour, the prehospital team needs to do its best to promptly treat and transfer the patient to the closest hospital, if that hospital capacity has not been exceeded. IPCI has major implications on patient distribution in MCE (Figure 3).

Figure 3 (Color online) Components of Injury to Hospital Interval (IHI)

Time Factor (TF)

TF takes into account the MTA for a particular level of acuity according to the current values described in the literature. It is defined as the proportion of critical and moderate patients with an IHI under the MTA. Since T1 and T2 have different MTAs, the TF naturally has two components; TF1 for T1 and TF2 for T2.

Capacity Factor (CF)

The CF takes into account the capacity of designated hospitals receiving MCE patients. It is defined as the proportion of T1 and T2 patients received by the designated hospitals without exceeding their per-hour surge capacities, compared to the total number of T1 and T2 received.

Medical Rescue Factor (R)

The R is the overall performance indicator for prehospital medical response, and is a derivation of both the TF and CF. It is calculated as R = TF × CF.

Discussion

Four quantitative parameters (IPCI, IHI, TF, CF), in addition to one derived parameter (R), were modeled for the prehospital response to trauma-related MCE.

Both IPCI and IHI are important in guiding the prehospital response and distribution of patients during an MCE. An example to illustrate this point is an urban MCE with two T1 casualties; one with IPCI of 15 minutes and another with IPCI of 35 minutes. Taking the mean intervals by Carr et alReference Carr, Caplan and Pryor19 (on-scene time interval of 13.4 minutes) and Spaite et alReference Spaite, Valenzuela and Meislin13 (patient access interval of 1 minute and delivery interval of 3.5 minutes), it takes approximately 16 minutes from patient contact to the completion of patient delivery, excluding the transport time (on-scene interval minus patient access interval plus delivery interval=13.4 − 1 + 3.5 = 16). Therefore, the first T1 needs to be transported to a hospital where the transport time is less than 29 minutes (60 − 15 − 16 = 29) to keep its IHI below the MTA of one hour. However, the second T1 needs to be transported to a hospital where the transport time is less than nine minutes (60 − 35 − 16 = 9). The values of both intervals (IPCI and IHI) should be documented for every T1 and T2 patient. There are several reasons to support the selection of these parameters. First, prompt identification, initial medical care, and transport of T1 followed by T2 casualties, are the raisons d’être of the whole process of prehospital medical rescue efforts in MCE. Second, many factors might delay patient contact from the time of injury (event); for example, unavailability of ambulances, search and rescue, security and safety, extrication and decontamination efforts. The IPCI takes all of these factors into consideration. Third, the selection of these two parameters, as specified above, holds the prehospital system accountable for an organized and informed distribution of every T1 and T2 casualty.

These parameters build upon the existing model proposed by Spaite et alReference Spaite, Valenzuela and Meislin13 used by several prehospital systems in their daily operations. The model is flexible enough to accommodate treatment areas established next to the scene or any expected changes in transport times in MCE, such as traffic or other potential delaying factors. Two major assumptions are made in this model: time of injury is assumed to coincide with the time of occurrence of the MCE, and any treatment established around the scene area is considered part of the initial prehospital treatment, and not part of the “definitive treatment” assumed at the hospital.

Time Factor (TF) as a Performance Indicator

A numerical value of 1 for the Time Factor (TF = 1) is the quantitative benchmark for prehospital performance in MCE. The number 1 is chosen, since the aim is to have all the IHIs (100%) for all T1 patients fall within the MTA for T1 (one hour or golden hour), and all IHIs for T2 fall within MTA2 (four to six hours or Friedrich's time). TF may vary from 1 to 0.001, which is selected by default to be the lowest possible value. For example, if nine out of 10 T1 (critical) trauma casualties had an IHI under an hour, the value of TF1 would be equal to 9/10 = 0.9. If all of the IHIs were less than one hour, TF1 would have met the benchmark of 1. The same principle applies to T2; if nine out of 10 T2 casualties had an IHI under four hours, the value of TF2 would be equal to 0.9. If all of the IHIs were less than four hours, TF2 would have met the benchmark of 1 (Figure 4).

Figure 4 (Color online) Example of calculating the Time Factor (TF) for T1 patients

Since there are two time factors (TF1 and TF2), the overall TF would be based on the proportionate numbers of T1 and T2, to give more weight to the time factor (TF1 or TF2) with the larger number of casualties, as opposed to just getting the average. Therefore,

where P1 = T1/(T1 + T2) and P2 = T2/(T1 + T2). This proposed model would stand even if new reference points for maximum time allowed were adopted in the future. In addition, the concept of TF may be applied to non-traumatic injuries (e.g., chemical, biological, radiological) when evidence-based data on MTA1 and MTA2 for those types of injuries become available. At the 1997 Centennial Olympic Park bombing in Atlanta, Georgia (USA), all 111 injured patients were evacuated to 11 area hospitals within 30 minutes of the event by 30 EMS units.Reference Feliciano, Anderson and Rozycki34 Assuming all IHI for both T1 and T2 were within 30 minutes, the performance of the prehospital medical system as it relates to TF was adequate (meeting the benchmark of 1).

Capacity Factor (CF) as a Performance Indicator

Distributing patients to designated hospitals should not only take into account the TF as illustrated above, but also the different capacities of designated hospitals. The proposed quantitative Hospital Acute Care Surge Capacity (HACSC) model that estimates the per-hour hospital surge capacity was adopted in this study to calculate the CF.Reference Bayram, Zuabi and Subbarao35 HACSC is equal to the number of ED beds (EDB) divided by the average ED time (EDT) for T1 and T2 combined, (HACSC = #EDB/EDT). EDT is estimated to be 2.5 hours in traumatic MCE.Reference Bayram, Zuabi and Subbarao35

Despite the controversy regarding the Maximum Time Allowed,Reference Newgard, Schmicker and Hedges20-Reference Cowley29 one overarching paradigm in EMS has been that the shorter the IHI, the better the prehospital response. However, this paradigm needs to account for the different capacities of the designated hospitals. For example, if the IHIs for all T1 casualties, from injury until the completion of transfer of care, fall within one hour, but all are taken to a single hospital where the capacity is exceeded, the shorter IHIs in this case may have a detrimental effect on the medical outcome of those T1 casualties.Reference Hirshberg, Scott, Granchi, Wall, Mattox and Stein36 Significantly, the model proposed in this study quantitatively links the prehospital response to the capacity of designated hospitals. A way not to exceed the pre-determined per hour surge capacities of different hospitals is through continuous communication between EMS and the designated hospitals on the number of T1 + T2 cases received each hour.

The CF is the proportion of T1 and T2 patients received by the designated hospitals without exceeding the per-hour surge capacities, compared to the total number of T1 and T2 received. For example, if 35 T1 and T2 patients (out of a total of 41) were transported to various designated hospitals without exceeding their per-hour hospital surge capacities, the value of CF would be 35/41 = 0.85. If all T1 and T2 were transported without exceeding the per-hour surge capacity of any of the receiving hospitals, the value of CF would be equal to 1, which is the maximum numerical value possible because it is a proportion.

A numerical value of 1 for the Capacity Factor (CF = 1) is set to be the quantitative benchmark for prehospital performance in MCE as it relates to the capacity of hospitals. CF can vary from 1 to 0.001, which by default is selected to be the lowest possible value.

Medical Rescue Factor (R)

R, an overall performance indicator for prehospital medical response, is calculated by multiplying the TF by CF.

It takes into account both how rapid the prehospital medical response was, and the important factor of hospital capacity. Since the maximum possible value for both TF and CF is 1, the maximum value of R would also be 1. The minimum value of R is selected, by default, to be 0.001.

Soldier Field Multiple Casualty Event Example

Taking a hypothetical example of an MCE from high-yield explosives occurring in Chicago's Soldier Field during an American football game on a Sunday at 2:37 PM, assume the mean time interval from patient contact to the completion of patient delivery to receiving hospitals, excluding transport time, is 16 minutes. One can predict which trauma centers can receive critical patients within the Maximum Time Allowed of one hour (Table 2). If ambulances make contact with the first group of triaged T1s 15 minutes after the injury (IPCI of 15 minutes), hospitals that have transport times of less than 29 minutes can receive this group of critical patients (T1) and still fall within the one hour mark (60 − 15 − 16 = 29 minutes). If a particular EMS region has different target numbers for on-scene and delivery intervals, these numbers can be adjusted accordingly. Since the transport intervals of all six Level I Trauma Centers in the Chicago area are <29 minutes, all of those centers can receive T1 patients from the scene. It is important to note that the transport time to Advocate Christ is very close to the 29 minutes mark (Figure 5).

Table 2 Estimated IHI and HACSC of Chicago area Level I Trauma Centers

Figure 5 (Color online) Geographical location of Soldier Field and Chicago area Level I Trauma Centers with their corresponding transport intervals

If the IPCI is 25 minutes because of triage or security issues, trauma centers within 19 minutes can receive this group of T1 patients (60 − 25 − 16 = 19), and still fall within the MTA1. In this latter scenario, Loyola and Advocate Christ cannot receive these T1 patients. Note that in mass casualty events, medical centers that are not designated as Level I may need to be included in the care of critical patients. In MCE, many of the casualties arrive to the closest hospital by private transportation, with the risk of overwhelming its capacity. Therefore, it may be prudent for the EMS system to transport T1 and T2 casualties triaged early on to further hospitals, as long as their expected IHIs are within the corresponding MTAs.

In summary, the need to incorporate the newly defined time intervals (IPCI, IHI, TF, CF, R) as an extension of regular daily measurements of EMS activities is important (Table 3). These intervals can become part of performance measures used to assess system readiness for MCE. Going back to the 1997 Centennial Olympic Park bombing in Atlanta, numerous questions can be posed: What were the IHIs for each T1 and T2? What were the values of TF1 and TF2 and subsequently the overall TF? Were any of the hospital surge capacities (per-hour surge capacity) exceeded? What was the value of the CF? These issues are at the core of prehospital medical response in MCE, and in direct relationship to the hospital response. Although a very difficult task in reality, the earlier, more complete, and more accurate the triage process is, the more organized the prehospital medical response can be. An early, complete, and accurate triage process enables accurate information to be conveyed to the Event Commander, who contributes to the decision-making process related to the number of ambulances to be mobilized, the necessity and feasibility of a forward medical post, the number and identity of designated hospitals, and the need to request acute medical assistance based on predetermined prehospital and hospital-based capacities. An early, complete, and accurate triage process fulfills three functions. First, it buffers the tendency of transporting the first casualties encountered, sometimes with minor injuries, instead of saving such resources for critical patients first. Second, it allows for organized distribution, and adequate tracking, of casualties (who went where). Third, it sets the ground for a systematic prehospital approach.

Table 3 Summary of concepts

The proposed model, quantifying essential parameters in prehospital medical response to trauma-related MCE, has several strengths. A major strength is that it builds upon an existing model of prehospital time interval (Spaite et al), already in use by many EMS systems, both in the United States and internationally. It also provides two quantitative time intervals (IPCI and IHI), that would help EMS distribute patients in an informed and organized manner. The IPCI takes into consideration any delays to patient access, such as search and rescue or decontamination. In addition, the model provides a quantitative parameter (medical rescue factor), to evaluate the overall performance of the prehospital system based on both prehospital time intervals (represented by the Time Factor) and the capacity of designated hospitals (represented by the Capacity Factor). Model parameters can be used not only to guide the EMS response to MCE, but also as objective measures for quality improvement. Fundamental concepts from this quantitative model would still be valid even if new reference times for MTA are established. In addition, these concepts maybe extended to other types of MCE injuries. Finally, although Carr's average interval times were used for illustration purposes, any EMS region can use its quantitative time interval targets and develop a more refined model that is particular to that specific region.

Limitations

The proposed model has limitations. First, it assumes that the occurrence of injury coincides with that of the MCE, which is sometimes not the case. However, if another distinct sequential MCE occurs (e.g., collapse of bridge occurring at a later time from an original MCE, like an explosion), this fact needs to be taken into account. Second, the values of MTA in trauma patients for critical and moderate patients are controversial, as these values might be variable with different organ systems affected even within the same triage category. As more research related to MTA is performed in the future, the numbers can be adjusted, while the concept remains the same. Finally, many EMS systems do not measure all of the various prehospital time intervals to the level of detail described by Spaite et al, which means many EMS regions do not have quantitative benchmarks that can be used in MCE response planning. Finally, this modeling of the prehospital medical system is largely based on blast-trauma literature, and research regarding whether it can be applied to other types of injuries is warranted.

Conclusion

The different parameters modeled above (IPCI, IHI, TF, CF, and R) constitute a framework for a new quantitative model of the prehospital medical response in trauma-related MCE. Prospective studies of this model are needed to validate its applicability in actual MCE.

Abbreviations

- CF:

Capacity Factor

- EMS:

Emergency Medical Services

- HACSC:

Hospital Acute Care Surge Capacity

- IHI:

Injury to Hospital Interval

- IPCI:

Injury to Patient Care Interval

- MCE:

Multiple Casualty Events

- MTA:

Maximum Time Allowed

- R:

Medical Rescue Factor

- TF:

Time Factor

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Louis Hondros, Mazen El-Sayed, and Jomana Musmar for their editing efforts. We would also like to thank Ahmad Bayram for his technical assistance.