Introduction

Disaster, man-made or natural, can occur at any time anywhere in the world. From 2005 through 2014, the total damage world-wide as calculated by the United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNISDR; Geneva, Switzerland) was US$1.4 trillion, with 0.7 million people killed and 1.7 billion people affected.1 The risk of exposure to natural hazards and climate change, terrorism, and epidemics with serious health consequences is likely to increase. Internationally, society spends an enormous amount of money and effort on disaster preparedness: attempts to reduce vulnerabilities of communities, to be able to deal with the consequences of disasters, and to recover from the effects of disasters.2,3 Within disaster preparedness, health care plays an indispensable role, since disasters lead to large numbers of people seeking medical attention.Reference Bayntun, Rockenschaub and Murray4,Reference Djalali, Della Corte and Foletti5 Within health care disaster preparedness, hospitals deserve separate consideration. Their role in disasters is vital in that they provide definitive, life-saving, and emergency care for the injured.Reference Dhawan, Mehrotra and Basukala6

The significance of disaster preparedness in hospitals is not debated; however, different authors seem to approach the subject differently, with different levels of analysis and different degrees of complexity. For instance, some authors try to develop frameworks for disaster response in health care,Reference Hanfling, Altevogt and Gostin7 while others focus on the individual employee in the health care organizations,Reference Daily, Padjen and Birnbaum8 or on instruments to measure public health preparedness.Reference Asch, Stoto and Mendes9

Differences in focus, approach, and complexity are potential obstacles for the transfer of knowledge and lessons learned between scholars, but more importantly, they can hinder the development of actual preparedness in hospitals. In order to help hospitals to prepare for disaster, a common basis is needed.

This study sought to contribute to that common basis by a systematic assessment of definitions and operationalizations of disaster preparedness in hospitals and, subsequently, by developing an all-encompassing model incorporating different perspectives on the subject.

Methods

Databases and Search Strategy

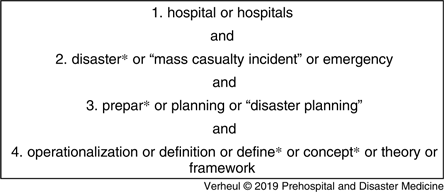

A systematic review of the relevant literature was conducted, based on the guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA). To identify relevant studies, an electronic search in five scientific databases ‐ Scopus (Elsevier; Amsterdam, Netherlands); PubMed (National Center for Biotechnology Information, National Institutes of Health; Bethesda, Maryland USA); Web of Science (Thomson Reuters; New York, New York USA); Disaster Information Management Research Center (DIMRC; Bethesda, Maryland USA); and SafetyLit (SafetyLit Foundation Inc.; San Diego, California USA) ‐ was performed. The searches were initially conducted in 2017, with a final update and check in December 2018. The search strategy was based on a combination of search terms in title and abstract (Table 1 and Table 2). A research librarian worked with the reviewers to develop the search strategy and select appropriate databases for the search.

Table 1. Search Strategy

Table 2. Additional Search Strategy

Eligibility Criteria and Selection

Peer-reviewed studies with disaster preparedness concepts, definitions, criteria, or operationalizations in a hospital setting were included. In this research, operationalization is used in the meaning Greenwood gave to the term: “To operationalize a concept is to identify those variables in terms of which the phenomenon (…) can be accurately observed. Variables thus identified become the indexes of the phenomenon.”Reference Greenwood10

Studies published in languages other than English, or with no full-text available, were excluded, as were articles that described themes other than health care, works outside an emergency or crisis context, or articles on prehospital care. Screening took place in three rounds. During the first round, two authors (MV and MD) independently screened articles retrieved on title and abstract, based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, and decided on eligibility by consensus. In the second round, the full-texts of the selected studies were screened. Reading the full-texts revealed that some terms were missing in the original search string. For this reason, an additional search (Table 2) was conducted in the same five databases.

Data Extraction and Analysis

For each included study, a data extraction form was filled out to systematically extract information on the year of publication, journal, country of origin, general focus of the paper, preparedness definitions (quoted directly from the study), preparedness operationalizations, and the aims of preparedness. After having extracted and structured the definitions, operationalization, and aims presented in the works, a model for hospital disaster preparedness was developed. The intention beforehand was to create a conceptual model, reflecting perspectives and components recognized as relevant by different authors, as well as the interrelations between the components, and to make, if possible, a distinction between the essential features of preparedness on the one hand and their determinants on the other.

Results

Number of Studies Found

The original search yielded 2,057 articles (Figure 1). The first author screened these for doubles (338). All titles and abstracts of the remaining 1,719 were screened by both authors for relevance and significance. Both researchers agreed on the exclusion of 1,318 articles, the inclusion of 175 articles, and were undecided in 226 cases. All undecided cases were included. These 401 articles were screened in full-text in round two by the first author, while the second author checked samples.

Figure 1. PRISMA Representation.

The extended search resulted in an additional 21 articles, which were again screened by both reviewers based on title and abstract for relevance and significance. In this third round, six extra articles were included.

After the full-text screening of 407 articles, a total of 375 articles were excluded for various reasons. Articles that focused on prehospital preparedness, for instance, were not deemed relevant to answer the research question and were excluded for that reason. The screening of the reference lists of all articles led to five extra articles to be included.

The final search in December 2018 followed the same steps as described above and yielded three more articles. Eventually, the total screening process yielded 40 articles to be included in this study.

Description of Included Studies

Appendix 1 (available online only) contains data extracted from each included study using data extraction forms. The publication years of the articles included in the study ranged from 2004-2018, thus spanning more than one decade. The studies were found in 25 different journals, with authors from six different countries. The general focus of the studies has lain on measuring or assessing hospital disaster preparedness in 16 of the studies, while the other 24 studies focused on the effects of preparedness activities (N = 4), the definition of preparedness (N = 3), or other related themes (N = 17).

Findings on Preparedness Definitions

Table 3 gives an overview of the original definitions found in the literature.Reference Daily, Padjen and Birnbaum8,Reference Asch, Stoto and Mendes9,Reference Fraser11–Reference Tang21 Of the 40 articles included in this study, 13 provided an original definition of preparedness and five authors referred to definitions from other articles.Reference Paganini, Borrelli and Cattani22–26 Definition was defined as “a statement that explains the exact meaning of a word or phrase.”27 The articles included in this study contained 13 different definitions of preparedness. What these definitions had in common was that they described preparedness in terms of: (1) an action (managing,Reference Kaji, Koenig and Lewis15 planning,Reference Tang21 or maintainingReference Barbera, Yeatts and Macintyre13); (2) aimed at minimizing or reducingReference Slepski16 certain consequences (challenges in general, or more specifically: increased and potentially unusual medical needs of affected populations, overwhelmed routine capabilities, or a progressive influx of patientsReference Daily, Padjen and Birnbaum8,Reference Barbera, Yeatts and Macintyre13–Reference Kaji, Koenig and Lewis15 ); that (3) needed to be carried out adhering to particular quality criteria: effective, appropriate, constructive, adequately, or quickly.Reference Fraser11

Table 3. The 13 Original Definitions of Disaster Preparedness

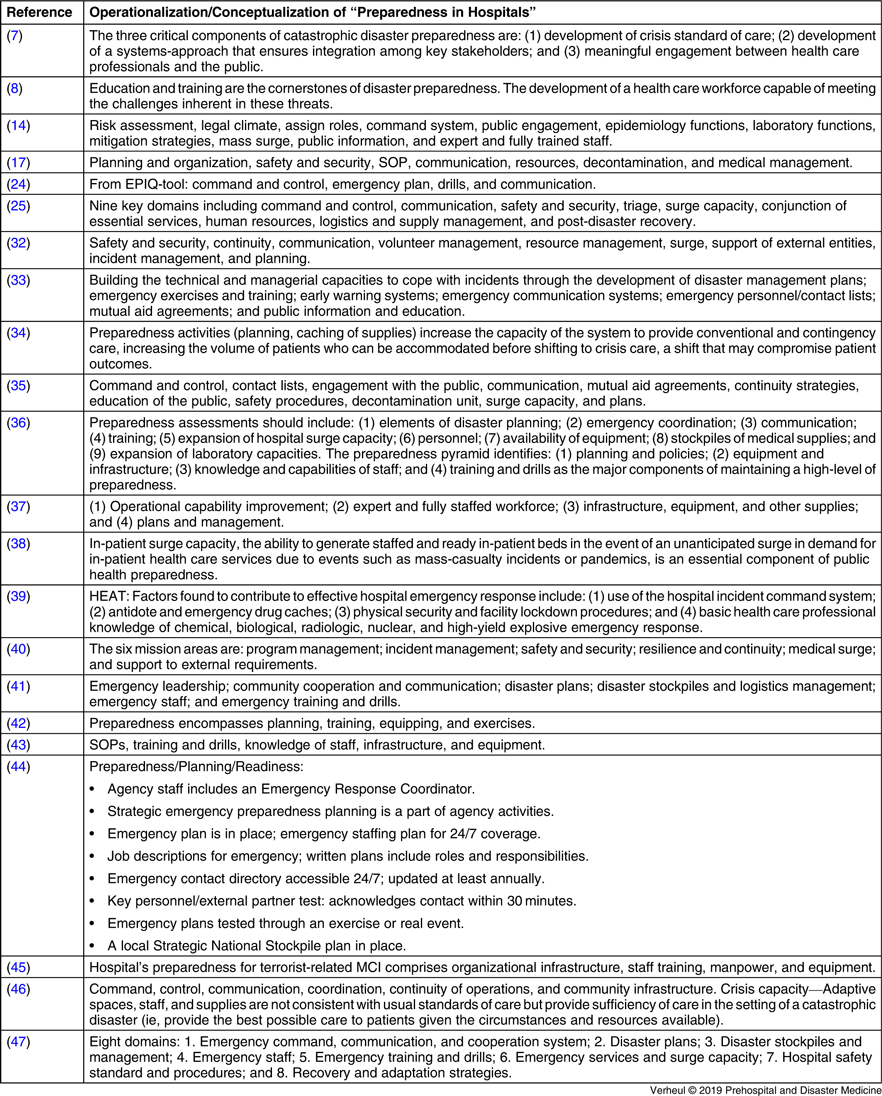

Findings on Operationalization of Preparedness

Four articles referred to operationalizations in other articles.Reference Zhong, Hou and Clark28–Reference Adini, Laor, Hornik-Lurie, Schwartz and Aharonson-Daniel31 Table 4Reference Hanfling, Altevogt and Gostin7,Reference Daily, Padjen and Birnbaum8,Reference Nelson, Lurie, Wasserman and Zakowski14,Reference Olivieri, Ingrassia and Della Corte17,Reference Baack and Alfred24,25,Reference Mcarthy and Brewster32–Reference Zhong, Clark, Hou, Zang and Fitzgerald47 shows the 22 articles that gave an original operationalization of preparedness in hospitals.

Table 4. The 22 Original Operationalizations of Preparedness

Abbreviations: MCI, mass-casualty incident; SOP, standard operating procedure.

Analysis of the operationalizations leads to nine recurring components in the operationalizations in Table 5.

Table 5. Operationalization of Preparedness: Nine Components

a In this table, mutual aid agreements (mentioned by five authors) and contact lists (mentioned by three authors) are categorized under the component of disaster plans and protocols.

Findings on the Aims of Disaster Preparedness

Seven articles described the aim of disaster preparedness (Table 6).Reference Daily, Padjen and Birnbaum8,Reference Nelson, Lurie and Wasserman12,Reference Archer and Synaeve19,Reference Ciottone, Keim and Ciottone23,Reference Janati, Sadeghi-bazargani, Hasanpoor, Sokhanvar, HaghGoshyie and Salehi29,Reference Djalali, Castren and Khankeh30,Reference Zhong, Clark, Hou, Zang and Fitzgerald47

Table 6. Aims of Preparedness

Discussion

Definitions

The objective of this review was to describe how disaster preparedness in hospitals has been defined and operationalized in international literature. The 40 articles included in this study contained 13 different definitions of preparedness – apparently authors feel little need to define what preparedness is, and if they feel this need, it is not common to refer to definitions developed by international colleagues. What these definitions collected in this review have in common is that they describe preparedness in terms of: (1) an action; (2) aimed at minimizing or reducing certain consequences; that (3) needs to be carried out adhering to particular quality criteria.

The context of the author that gave the definition may have influenced the content and wording of that definition. Further research needs to take these contextual differences into account, since that will positively influence the exchange of insights related to the subject of disaster preparedness in hospitals. Researchers propose that stakeholders involved in hospital preparedness activities carefully consider these aspects when operationalizing hospital preparedness in their own contexts.

Operationalizations

What these definitions do not provide is an indication of how to prepare. They are not informative about how to observe, measure, or promote preparedness. The operationalizations of disaster preparedness offer more clues.

An examination of the operationalizations of disaster preparedness in the articles yielded nine recurring components (or indexes in terms of Greenwood – which does justice to the idea that scores per component can range from high to low).Reference Greenwood10 So, disaster preparedness can be observed, measured, and promoted by taking at least nine different components into account. In the articles included in this study, not one author covered all nine components. The authors’ emphasis might be an expression of their habits, beliefs, and ideas about disaster preparedness in hospitals. It is like the old tale in Sufism about the blind men and the elephant: every individual author describes preparedness using personal experiences that only capture an aspect of location of the animal. Only the combination of all observations enables to sketch an image of the whole elephant or, in the context of this study, the broader concept of disaster preparedness.

Synthesis and Model Construction

The next step is to synthesize the results and to use them to create a conceptual model, reflecting perspectives and components recognized as relevant by different authors, as well as the interrelations between the components. The definitions in Table 3 consider preparedness as a capability or capacity to respond to health needs and morbidities disaster-affected populations (external focus) and the ability to stay operational under critical conditions when the demand for care and the availability of time and resources is scarce (internal focus). The analysis of the operationalizations resulted in the nine components listed in Table 5. In the disaster preparedness nonagon, as shown in Figure 2, these components form the center of the model. A first assumption based on the literature review is that all components matter when it comes to understanding the preparedness status and the potential for improvement in different health care contexts.

Figure 2. Nonagon for Disaster Preparedness in Hospitals.

Secondly, although the studies provide little information on the associations between the components, it is imaginable that they are all interrelated in a certain way and that activities aimed at enhancing one particular component should be considered in relation to other components. Disaster plans and protocols that, for example, consider crisis communication and public engagement strategies, should also anticipate on the availability of staff and equipment and measures aimed at continuity and staff safety. The second assumption – the idea that components should be approached in combination – is not supported by scientific evidence yet and is to be verified.

Thirdly, since the essential features of preparedness are likely to depend on particular determinants, an outer ring with conditions was added to the model. The material analyzed in this article contains little detailed information on specific conditions, although some authors approach education, training, and exercise as such (Table 3 and Table 4). In that case education, training, and exercise can be seen as a characteristic of preparedness as well. An alternative position is that these activities are conditions for the status of the nine components/indices. Both positions can be defended. At the moment, the nature and the working mechanisms of the conditions for preparedness and the nine components clearly deserves more study in order to strengthen the evidence base of hospital preparedness. A fourth assumption, namely, is that education, training, and exercise contribute to preparedness and its components. Nevertheless, at the moment, little is known about the effects of education, training, and exercises on the level of preparedness.Reference Verheul, Dückers, Visser, Beerens and Bierens48,Reference Hsu, Thomas, Bass, Whyne, Kelen and Green49 This also applies to the knowledge about the effects on preparedness on the actual performance during real disasters and major incidents.

The fifth assumption is that it is important to approach the preparedness components in the center of the model in relation to a particular aim – without well-defined aim, it is impossible to disentangle the value of resources invested on the preparedness level.

Whether in the context of the model or not, the nine components should be developed through further research. Although the assumptions behind the model need to be tested, in its current form, the model can add focus in aligning the efforts of hospitals and other health care institutions, professionals, educators and trainers, policy-makers, and researchers to assess and enhance disaster preparedness.

Limitations

This review has several limitations. One could question the interpretation of the definitions and operationalizations as described in the article. Second, because only articles written in English were included, the researchers may have missed some valuable information in articles written in other languages. Third, the researchers focused on publications in peer-reviewed journals, and did not extensively look for grey literature, thus possibly missing some information. Fourth, as the absence of a preparedness definition or operationalization was an exclusion criterion, it is possible that the researchers overlooked interesting articles that did not explicitly define or operationalize preparedness. Fifth, the researchers cannot be certain that all elements of disaster preparedness where captured in the nonagon, since they only included elements found in literature. Sixth, the article focusses only on disaster preparedness in hospitals, leaving other equally important areas, such as Emergency Medical Services, undiscussed. Finally, the nonagon model as visualized is the result of an attempt to structure different factors and the relations between them. Obviously, alternative interpretations are possible. It is important to further develop and test models like these. The ultimate test of any preparedness model is how well it predicts the actual performance of professionals and organizations during disasters.

Conclusion

The aim of this research was to contribute to establishing a common basis for disaster preparedness in hospitals. Besides a modest number of definitions, the literature review pointed at nine preparedness components that could be brought together in a conceptual disaster preparedness model. The results of this synthesis can guide hospitals and other institutions in the development of their disaster preparedness, and might guide scholars in further research aimed at understanding the working mechanisms of disaster preparedness. Currently, little consensus exists on the aim of disaster preparedness and the best way to realize them in different circumstances. In order to make preparedness activities as effective as possible, it is important to strengthen the scientific evidence base.

Conflicts of interest

none

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049023X19005181