Introduction

The burden of trauma has been rising steadily across the Caribbean over the past four decades,Reference Scarlett, Mitchell and Amata 1 - Reference Francis 7 with interpersonal assaults featuring prominently. These trends have become so discernible that several governments in the Caribbean have proclaimed the existence of a State of Emergency (SOE) in their respective nations.

A SOE refers to the presence of an imminent threat of a sufficiently extensive scale that endangers public safety and the existence of state. 8 Several Anglophone Caribbean countries have proclaimed a SOE in order to control epidemics of interpersonal violence: Grenada declared a SOE in 1983 after the assassination of prime minister Hon. Maurice Bishop;Reference Levitin 9 St Kitts and Nevis declared a SOE in 1993 following violent protest demonstrations after prime minister Hon. Dr. Kennedy Simmonds assumed rule after forming a coalition government; 10 and Jamaica declared a SOE in 2010 during bloody protests surrounding the arrest and extradition of notorious drug lord, Christopher Coke. 11

Interpersonal violence also became epidemic in Trinidad and Tobago, reaching crisis levels in 2010 when it prompted the nation’s government to declare a SOE. 12 During this period, the government imposed a nation-wide curfew limiting movement in public spaces to essential services only. In addition, the police and army were granted increased powers to conduct searches without warrants and to make expedited arrests. This study sought to evaluate the effect of this intervention on the number of admissions for penetrating trauma from interpersonal violence in Trinidad and Tobago.

Materials and Methods

The Port of Spain General Hospital (POSGH) is the main tertiary referral trauma center in Trinidad and Tobago. This is an 850-bed facility that serves a catchment population of approximately 650,000 persons.Reference Kirsch, Hilwig, Holder, Smith, Pooran and Edwards 13 The hospital is located in the country’s capital, the most densely populated region, 14 and arguably, one of the most violent parts of the island.

Trauma victims usually present to the emergency room and are seen immediately by emergency room physicians who commence resuscitation following Advanced Trauma Life Support protocols. Surgical consultations are routinely sought when trauma patients are seen. Once the patients are stabilized, the surgical teams continue management and organize further investigations or transfer to the operating room, as appropriate.

The local institutional review board granted approval to collect data retrospectively for this study. Three independent researchers retrieved paper-based records from the emergency room, operating rooms, and surgical intensive care units at the POSGH. Only patients with penetrating trauma were included in the study population.

Penetrating trauma was defined as any injury from an implement that entered the body to create a physical wound. Two types of penetrating injuries were defined: stab wounds and gunshot wounds. Stab wounds were defined as low-velocity injuries along the long axis of any narrow, pointed object. Gunshot wounds were injuries that resulted from a projectile fired from a weapon using gunpowder for propulsion and creating damage along the missile’s trajectory.

Hospital records were reviewed retrospectively in order to identify all patients with penetrating injuries who were treated from July 1, 2010 through December 30, 2012. This study period was chosen in order to include injuries one year before and one year after the declaration of the SOE that spanned from August 21, 2011 to December 5, 2011. 12

The hospital records were retrieved and the following information extracted: patient demographics, date of injury, trauma mechanism, injury details, and treatment details. Data were extracted from the hospital records and analyzed using the Statistical Program for Social Sciences (SPSS, Version 19; IBM Corporation; Armonk, New York USA). The data were categorized into three periods: pre, post, and during the SOE. The raw data for each period were tabulated and the means for each period were compared using a T-test. A P value <.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Over the study period, 1,067 patients with penetrating injuries from interpersonal violence were seen at the POSGH. This included 690 gunshot wound victims and 377 stab wound victims. All hospital records were retrieved and available for review for this study. There were no missing data.

When injury mechanisms were evaluated over the entire study period, there were significantly more gunshot wounds compared to stab wounds (64.7% vs 35.3%; P<.001). This trend was maintained during the SOE, when significantly more gunshot wounds than stab wounds were recorded (54.7% vs 45.3%, respectively; P=.37).

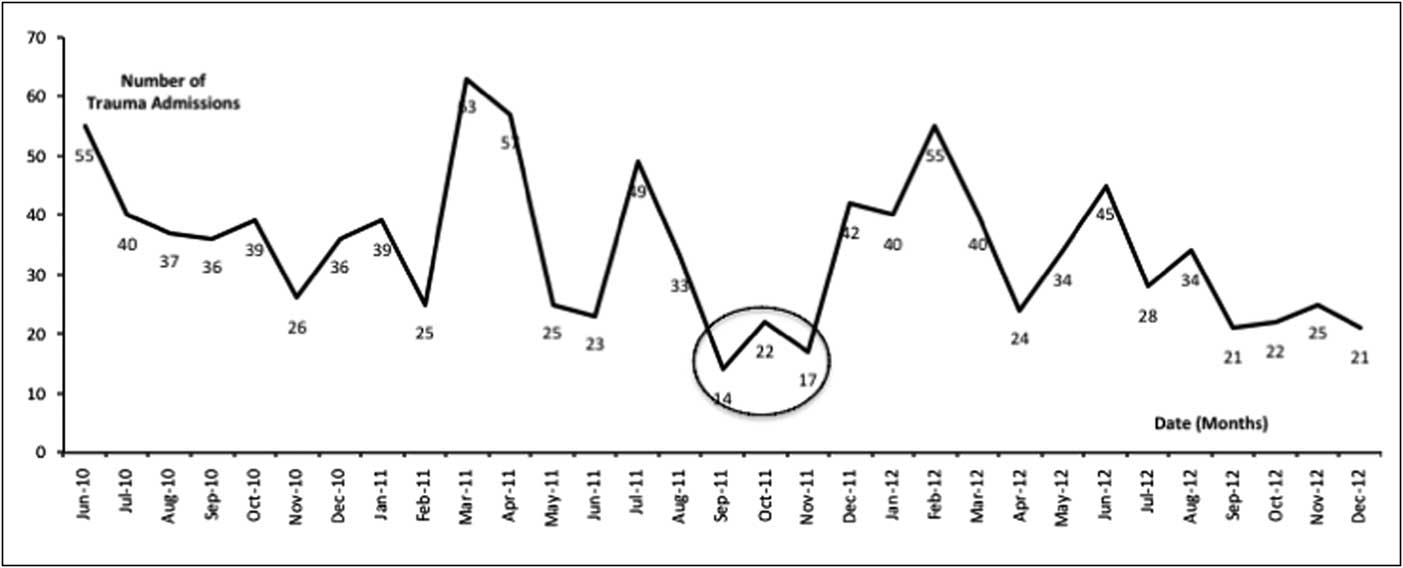

The SOE was declared by the prime minister on August 21, 2011 and lasted 106 days, coming to an end at midnight on December 5, 2011. 12 When the data were evaluated chronologically (Figure 1), there was a significant fall in the mean monthly number of admissions for penetrating trauma during the SOE when compared to the 12-month period before its imposition (17.7, SD=4.0 vs 38.9, SD=12.3, respectively; CI, 5.6-36.8; P=.0108). Immediately after the SOE was lifted, there was a sharp increase in penetrating injuries, but this was followed by a consistent downward trend. One year later (October 2012 through December 2012), the mean monthly number of admissions for penetrating trauma was similar to that seen during the SOE (22.7, SD=2.1 vs 17.6, SD=4.0, respectively; CI,-2.3-12.3; P=.1295).

Figure 1 Chronologic Patterns in the Number of Admissions for Penetrating Trauma due to Interpersonal Violence at the Port of Spain General Hospital. The State of Emergency period is encircled.

The trends in injury mechanisms were maintained for gunshot and stab wounds (Figure 2). The incidence of both injuries reduced sharply when the SOE was imposed. And both types of injuries increased after the SOE was lifted. However, there was an interesting relationship noted: the incidence of gunshot wounds remained low, with an average incidence below that of the SOE. The incidence of stab wounds, however, notably increased and accounted for most of the penetrating injuries after the SOE.

Figure 2 Chronologic Patterns in the Number of Admissions for Penetrating Trauma According to the Injury Mechanism. Broken black lines represent gunshot wounds and solid black lines represent stab wounds. The State of Emergency period is encircled.

Discussion

Trinidad and Tobago is a small island nation covering 1,980 square miles located just north of the South American Mainland. At the last national census, the population was estimated at 1,317,714 persons. 15 The island has had a stormy history. Since gaining independence from Britain in 1962,Reference Besson 16 there have been six events that were thought to be national security threats requiring declarations of SOEs.Reference Besson 16

The latest declaration of a SOE in Trinidad came on August 21, 2011 12 after a spate of violent attacks indiscriminately affected all sectors of society. These crimes allegedly were purported by members or a ruthless gang known as the G-Unit, armed with automatic weapons and financed by the drug trade. 17 The majority of gang activity was concentrated in “hot spots” near the capital city, Port of Spain. 18 This audit identified the majority of trauma cases since the POSGH is located centrally in the city of Port of Spain and receives the overwhelming majority of casualties from these conflicts. Additionally, there was no financial barrier to access care as the government of Trinidad and Tobago has a free health care policy with no user fees generated at any public health facility. 14

It was not surprising that firearms were the weapons of choice for these crimes, as they allow assailants to inflict injuries from a safe distance at which they would not be harmed. Therefore, it was no surprise that gunshot wounds accounted for the majority of penetrating injuries in this series (65%). Knives were significantly less likely (35%) to be used as weapons inflicting penetrating injuries in these attacks.

During the SOE, the government mobilized the military and police force to carry out intensified law enforcement operations with four specific aims: curtail interpersonal violence; recover illegal weapons; eradicate gangs; and seize illegal drugs. 12 , 17 To facilitate this, a curfew was imposed in areas identified as “hot spots” for criminal activity. 12 , 18 The military and police were also granted special powers to arrest and detain persons for up to 24 hours, with the possibility of detention for seven days, under the authority of a senior officer or magistrate. 12 , 17

The SOE lasted 106 days, from August 21, 2011 through December 5, 2011. 12 The government claimed success, alleging that the gangs were dismantled and criminal threats were averted across the nation. 12 Specifically, they reported that 8,178 persons were arrested for a variety of criminal offences by the end of the SOE. 12 This included 1,959 suspected criminals with outstanding warrants: 1,416 for drug-related offences, 449 for gang-related activity, and 94 for homicides. 12 As it related directly to weapons and contraband, the authorities seized 190 firearms, 13,550 rounds of illegal ammunition, 1,262 kg of marijuana, and 17 kg of cocaine. 12

Despite these reports, there was much discontent with many adversaries claiming that the SOE resulted in human rights abuses. 19 They suggested that ammunition and drug seizures were temporary, and stocks would soon be replaced. They also pointed out that half of the detainees accused of gang-related activity were released due to insufficient evidence, which the Director of Public Prosecutions blamed on poor evidence gathering. 20

However, this study has demonstrated a tangible intermediate-term benefit from the SOE with a sustained downward trend in the incidence of penetrating injuries. Another notable change was the significant reduction in gun-related crimes since the SOE. This may be secondary to large weapon seizures depleting ammunition and firearm reserves of the gangs.

While the temporal relationship between the SOE and the reduction in penetrating injuries is evident, the exact cause is difficult to ascertain. There are several other mechanisms to consider. For example, persons with access to illegal weapons may have been arrested or deceased after the SOE was lifted, thereby depleting the number of criminals who would perpetrate these crimes. Continued law enforcement efforts may have also removed weapons from the possession of criminals after the SOE was lifted. Alternatively, other social or community-based interventions may have also been effective in reducing criminal activities.

Some have argued that the SOE was lifted too quickly since there was a sharp rise in the incidence of penetrating trauma. However, it would not have been practical for the Government to prolong this SOE. The authors of this study believe that the government achieved its aim – to regain control over crime rates – that was evident by the reversion in penetrating trauma to the baseline levels by the end of the study period. More importantly, the authors believe that in prolonging the SOE, it would have been important for policy makers to have evaluated policies to prevent a resurgence of crimes and to have taken the opportunity to introduce social, legal, and political interventions aimed at sustaining the reduced crime rates.

Study Limitations

There are some limitations to this study. First, this study was carried out in a single institution. This was the main trauma center in the nation and it was located within Port of Spain near the gang-related activity and “hot spots” for trauma. However, the argument could be made that the patterns at this single institution may not have included a representative picture of injury patterns across the nation. Additionally, the study did not account for persons who were pronounced dead at the scene of injury, and so would not have been brought to the hospitals. Both of these factors could potentially affect the injury patterns seen in this study and should be taken into account.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated that there was a decrease in penetrating trauma within the community during the SOE, with a shift toward stab wounds and a decreased ratio of gunshot wounds at the main national trauma center one year after the SOE was lifted.