Introduction

Emergency first-response care includes rescue interventions such as identification, stabilization, and treatment of life-threatening conditions at the site of the event and support measures during medical transport.Reference Topete Tovar, Muñoz Fernández and Castillo López1 Prehospital care is provided to people who present medical or traumatic health events in different settings outside of the hospital setting. Emergency personnel who perform work in the prehospital setting usually attend to varied and complex emergencies in an environment of extreme conditions in terms of safety and resources, both in care personnel and in equipment and supplies that are difficult to control.Reference Payne and Kinman2 Therefore, first responders are exposed to multiple health risks (physical and psychological).Reference Wojtysiak, Wielgus and Zielińska-Więczkowska3 These risks can be preventable, mitigated, and treated in a timely manner to facilitate the recovery of caregivers. The nature of emergency work leaves these care personnel vulnerable to particular risks that most workers in other fields do not face. Among them, the high emotional demand and great stress to which they are exposed when fulfilling their responsibilities affects their psychological and physical well-being.Reference Krakauer, Stelnicki and Carleton4–Reference Melendez, González and González6

Coping strategies have been defined as the cognitive and behavioral skills used to face internal and external demands that can overwhelm the resources of an individual.Reference Lazarus and Folkman7 How people perceive and respond to stressful situations is key, particularly in the emergency responder scenario.Reference Loef, Vloet and Vierhoven8 Adaptive coping skills allow individuals to increase their ability to recover psychologically after stressful events, overcome long-term emotional damage, and reduce the psychological impact of exposure to stress, particularly in high-risk groups such as emergency personnel.Reference Bilsker, Gilbert, Alden, Sochting and Khalis9 In contrast, nonadaptive strategies are actions, thoughts, and feelings that avoid confronting and dealing with various stressors, which leads to negative effects on mental health, including the development of different mental disorders.Reference Andreo, Salvador Hilario and Orteso10,Reference Echeburúa and Amor11 Emergency responders are faced with traumatic events, and their resources, strategies, and capacities to cope with these stressful situations will determine their adaptation process.Reference Jurisová12

This systematic review is important because it examines the research related to the coping strategies of first responders at the international level, the methodologies that have been carried out in studies, and the significant findings and the best available evidence. The objective of the present work was to characterize the coping strategies used by first responders in the face of exposure to traumatic events.

Methods

This study followed the recommendations of the Cochrane collaborationReference Green and Higgins13 and guidelines established by PRISMA (PRISMA Checklist available as online supplementary material).Reference Liberati, Altman and Tetzlaff14 The protocol for this systematic review was previously published.Reference Diaz-Tamayo, Escobar and García-Perdomo15

Inclusion Criteria

Types of Design—Clinical trials; cohort studies; case-control studies; and observational, analytical, and descriptive studies were included in first-response populations.

Participants—Studies that evaluated coping strategies in prehospital care technologists, professional technicians in prehospital care, paramedics, emergency medical technicians, firefighters, first responders, graduates in medical emergencies, prehospital emergency personnel, prehospital medical care personnel, technicians in health emergencies, technologists in medical emergencies, and graduates in medical emergencies/prehospital care were included.

Instruments—Studies that used validated measurement instruments of coping strategies in this population were included.

Outcomes—The most commonly used coping strategies by first responders to emergencies after attending critical events were sought.

Exclusion Criteria

Studies including staff from other disciplines, such as doctors and nurses, who worked in emergency care services and volunteer personnel were excluded.

Information Sources

The following databases were searched: MEDLINE (Ovid) (US National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health; Bethesda, Maryland USA); EMBASE (Elsevier; Amsterdam, Netherlands); LILACS (Latin American and Caribbean Literature in Health Sciences) (Latin American and Caribbean Center on Health Sciences Information, Department of Evidence and Intelligence for Action in Health – EIH; Rua Vergueiro, Brazil); and the Cochrane Central Registry of Controlled Clinical Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Collaboration; London, United Kingdom) from the first registries through February 2022 (Appendix 1; available online only). To ensure the saturation of the literature, references of relevant articles identified through the search, conferences, thesis databases, Open Grey (INIST-CNRS - Institut de l’Information Scientifique et Technique; Paris, France), Google Scholar (Google Inc.; Mountain View, California USA), and Clinicaltrials.gov, among others, were scanned. No language restrictions were established.

Data Collection

Two researchers independently searched the different databases, reviewing each reference by title and abstract. Then, they scanned the full texts of the relevant studies, applying the pre-specified inclusion and exclusion criteria, and extracting the data from the full texts in the final selection. Disagreements regarding eligibility, quality, and retrieved data were resolved by consensus. Duplicate articles were eliminated.

Two trained reviewers who used a standardized form independently extracted the following information from each article: first author and year, geographic location, study design, age, title, objectives, inclusion and exclusion criteria, number of participants included, and instrument used, prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), coping strategies used, time, outcome definitions, results, and measures of association, if applied. The reviewers confirmed all data, making sure they were accurate.

Risk of Bias

The evaluation of the risk of bias for each study was performed using the Newcastle-Ottawa quality assessment scale, adapted for cross-sectional studies.Reference Herzog, Álvarez-Pasquin, Díaz, Del Barrio, Estrada and Gil16 This identified factors such as sample size and representativeness, characteristics of those who did not participate in the studies, validity of the instruments, comparison between groups, evaluation of the results, and the statistical test used.

Data Analysis/Synthesis of Results

The results were summarized in qualitative and descriptive terms due to the high heterogeneity of the findings.

Results

Selection of Studies

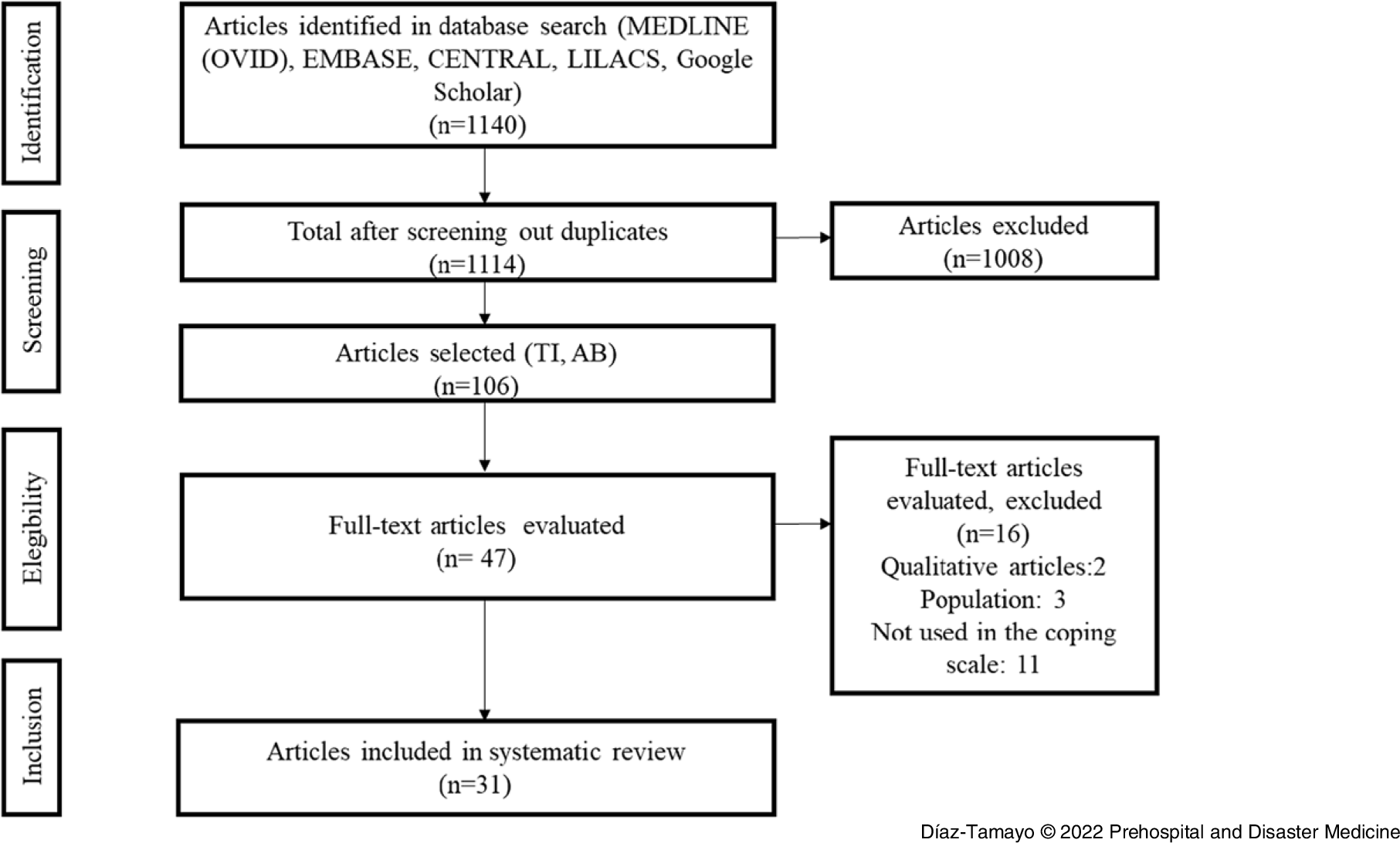

Once the search strategies were applied, 1,140 studies were found. Duplicate records were excluded, and after applying the eligibility criteria, 31 studies were included for the systematic review (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Selection of Articles.

Characteristics of the Included Studies

In the studies analyzed, a total of 3,012 firefighters, 2,876 paramedics, and 161 rescuers were presented, with ages ranging from 20 to 62 years, with a significant percentage of males, and with an average seniority in the position of 9.7 years. Of the 31 articles, 14 included firefighters, 13 included paramedics, and four included both populations.

The articles by Witczak-Błoszyk, et al;Reference Witczak-Błoszyk, Krysińska, Andriessen, Stańdo and Czabański17 Miller, et al;Reference Miller and Brown18 and Almutairi, et alReference Almutairi and Azza19 sought the relationship between burnout and coping mechanisms. Alghamdi, et al;Reference Alghamdi, Hunt and Thomas20 Meyer, et al;Reference Meyer, Zimering, Daly, Knight, Kamholz and Gulliver21 Soravia, et al;Reference Soravia, Schwab, Walther and Müller22 Lee, et al;Reference Lee, Park and Sim23 Witt, et al;Reference Witt, Stelcer and Czarnecka-Iwańczuk24 Kucmin, et al;Reference Kucmin, Kucmin, Turska, Turski and Nogalski25 Theleritis, et al;Reference Theleritis, Psarros and Mantonakis26 Clohessy, et al;Reference Clohessy and Ehlers27 Durham, et al;Reference Durham, McCammon and Allison28 Huang, et al;Reference Huang, Li and An29 and Tomaka, et alReference Tomaka, Magoc, Morales-Monks and Reyes30 established the relationship between symptoms of PTSD and coping styles and how these can be protective or risk factors. Regarding the workplace and exposure to traumatic events, Moskola, et al;Reference Moskola, Sándor and Susánszky31 Minnie, et al;Reference Minnie, Goodman and Wallis32 Boland, et al;Reference Boland, Mink, Kamrud, Jeruzal and Stevens33 Dowdall-Thomae, et al;Reference Dowdall-Thomae, Gilkey, Larson and Arend-Hicks34 Pisarski, et al;Reference Pisarski, Bohle and Callan35 Shakespeare-Finch, et al;Reference Shakespeare-Finch, Smith and Trauma36 and Halpern, et alReference Halpern, Maunder, Schwartz and Gurevich37 presented the coping strategies used by this population after these events. Fonseca, et al;Reference Fonseca, Cunha, Faria, Campos and Queirós38 Iwasaki, et al;Reference Iwasaki, Mannell, Smale and Butcher39 Piñar-Navarro, et al;Reference Piñar-Navarro, Fuente, González-Jiménez and Hueso-Montoro40 and Völker, et alReference Völker and Flohr-Devaud41 examined coping strategies related to stress. Sattler, et alReference Sattler, Boyd and Kirsch42 and Yang, et alReference Yang and Ha43 evaluated how coping strategies contributed to posttraumatic growth in these professionals. The articles of Chang, et alReference Chang, Lee, Connor, Davidson, Jeffries and Lai44,Reference Chang, Lee, Connor, Davidson and Lai45 evaluated the association between coping strategies and psychiatric morbidity. Oginska-Bulik, et alReference Oginska-Bulik and Langer46 investigated the relationship between personality traits and coping strategies. In addition, Vaulerin, et alReference Vaulerin, D’Arripe-Longueville, Emile and Colson47 identified the relationship between musculoskeletal injuries and coping strategies (Table 1).

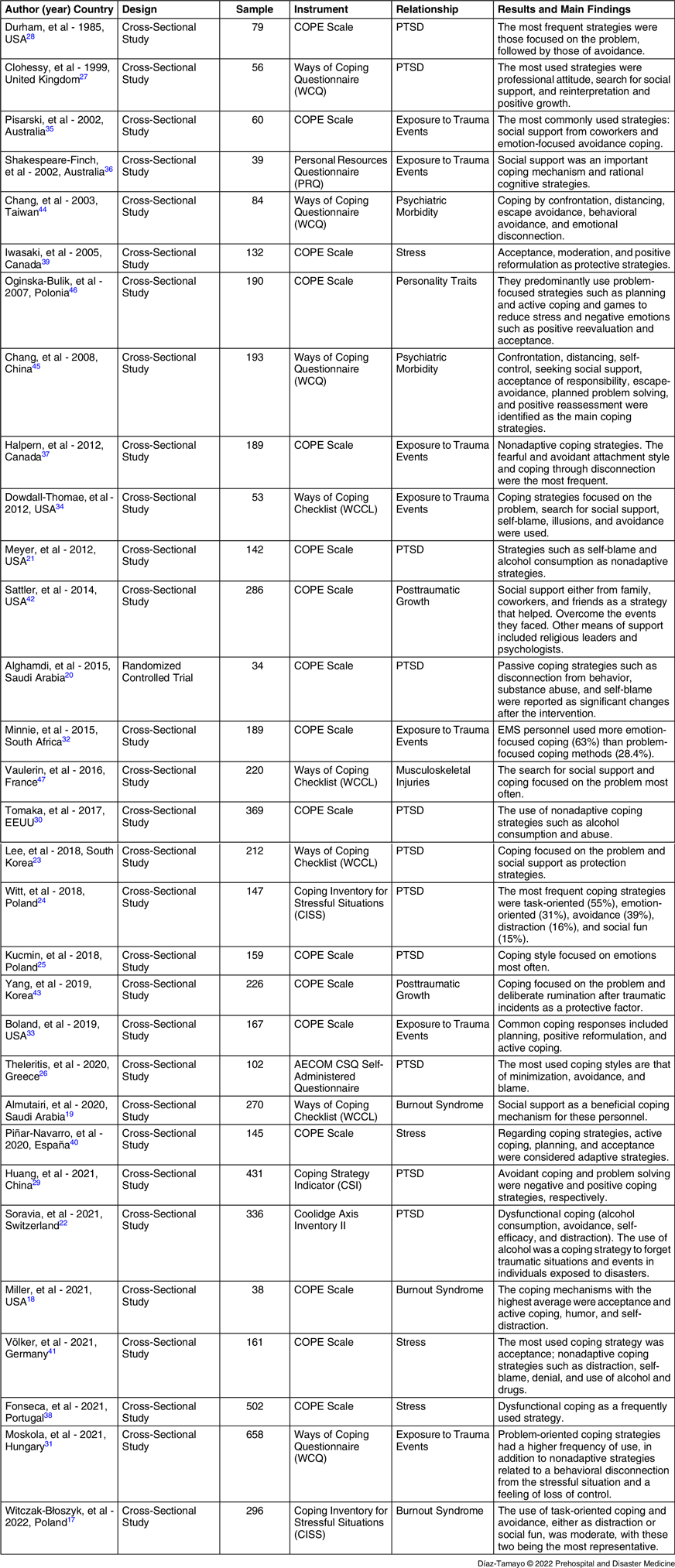

Table 1. Characteristics of the Included Studies

Abbreviations: COPE, Coping Orientation to Problems Experienced scale; PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder; EMS, Emergency Medical Services.

Five studies presented events that first responders considered traumatic experiences that they had difficulty processing and influenced their emotions, such as accidents or events involving children, accidents with multiple victims, injury or death related to a coworker, dealing with violent people, or suffering from direct physical or verbal threats at the scene of an incident, and witnessing suicides or the death of a patient in their care.Reference Soravia, Schwab, Walther and Müller22,Reference Kucmin, Kucmin, Turska, Turski and Nogalski25,Reference Moskola, Sándor and Susánszky31,Reference Minnie, Goodman and Wallis32,Reference Sattler, Boyd and Kirsch42

In relation to the studies reviewed, there are different instruments to evaluate coping strategies in the face of stress, mostly derived from the theory of Lazarus and Folkman, 1984.Reference Lazarus and Folkman7 In the present review, it was found that the most commonly used instruments were the coping scale COPE (Coping Orientation to Problems Experienced) with 55% of studies, the Ways of Coping Questionnaire (WCQ) with 13% of studies, the Ways of Coping Checklist (WCCL) with 13% of studies, the Coping Inventory for Stressful Situations (CISS) with seven percent of studies, and four different instruments with a total of 12%.

Characteristics of the Excluded Studies

Articles were excluded because they did not measure coping strategies through any instrument, the population was voluntary or had other health training different from that evaluated in this study, or the studies were qualitative. Regarding the type of study, no systematic reviews, topic reviews, protocols, or action plans were included.

Assessment of Risk of Bias

Thirty cross-sectional studies were included, of which six studies were unsatisfactory, mainly due to the lack of comparability,Reference Witczak-Błoszyk, Krysińska, Andriessen, Stańdo and Czabański17,Reference Miller and Brown18,Reference Kucmin, Kucmin, Turska, Turski and Nogalski25,Reference Clohessy and Ehlers27,Reference Iwasaki, Mannell, Smale and Butcher39,Reference Sattler, Boyd and Kirsch42 and three were good studiesReference Almutairi and Azza19,Reference Moskola, Sándor and Susánszky31,Reference Chang, Lee, Connor, Davidson and Lai45 (Table 2).

Table 2. Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (Modified) for Cross-Sectional Studies

In addition, the only clinical trial includedReference Alghamdi, Hunt and Thomas20 had an unclear risk of bias for the random sequence, allocation concealment, and other biases. Additionally, there was a high risk of bias for blinding, since it was open, and the result could have been evaluated subjectively (Figure 2A and 2B).

Figure 2. (A) Risk of Bias among Studies. (B) Risk of Bias within Studies.

Results of Individual Studies

First responders to emergencies are frequently at risk of presenting symptoms of PTSD due to the characteristics of their work, where they are exposed to highly stressful events and severe trauma. Of the studies reviewed in this study, 13 reported the presence of PTSD in the populations analyzed. Of these, two studies (Lee, et alReference Lee, Park and Sim23 and Huang, et alReference Huang, Li and An29) despite reporting the evaluation of this condition, did not report the data obtained in terms of PTSD. The study by Meyer, et alReference Meyer, Zimering, Daly, Knight, Kamholz and Gulliver21 reported a prevalence of four percent. The other ten studies reported a prevalence of PTSD between eight percent and 51%.

Nonadaptive Coping Strategies

The studies of Witczak-Błoszyk, et al;Reference Witczak-Błoszyk, Krysińska, Andriessen, Stańdo and Czabański17 Soravia, et al;Reference Soravia, Schwab, Walther and Müller22 Völker, et al;Reference Völker and Flohr-Devaud41 Theleritis, et al;Reference Theleritis, Psarros and Mantonakis26 Chang, et al;Reference Chang, Lee, Connor, Davidson, Jeffries and Lai44 Dowdall-Thomae, et al;Reference Dowdall-Thomae, Gilkey, Larson and Arend-Hicks34 and Meyer, et alReference Meyer, Zimering, Daly, Knight, Kamholz and Gulliver21 showed a frequent use of nonadaptive coping strategies, with avoidance or disconnection as a strategy to avoid difficult situations and to downplay the perceived stressful event to prevent experiencing or re-experiencing the stressful situation. The mechanisms of distraction and social fun, as strategies to avoid thinking about situations, and denial as an absence of acceptance of the situation, enable individuals to tolerate or support the emotional state generated by trauma and self-blame while avoiding the real problem. Huang, et alReference Huang, Li and An29 found that the cognition and negative evaluation caused by traumatic events can make people use avoidant coping more frequently.

Another avoidance strategy used by emergency personnel is to escape through the consumption of substances such as alcohol and drugs to generate emotional disconnection and alleviate symptoms of stress.Reference Tomaka, Magoc, Morales-Monks and Reyes30,Reference Halpern, Maunder, Schwartz and Gurevich37 According to Kucmin, et al,Reference Kucmin, Kucmin, Turska, Turski and Nogalski25 the coping style focused on emotions is also a maladaptive strategy that emergency personnel resort to due to the tendency to try to eliminate thoughts, images, or memories, resulting in greater accessibility to them and the activation of emotional memory, which in turn stimulates anxiety.

Miller, et alReference Miller and Brown18 found that humor was not a positive factor as a coping strategy in these personnel, since they resorted to this tool to try to downplay stressful situations.

Dysfunctional coping was explained by perceived stress after exposure to critical incidents, increasing the level of threat and cancelling the protective role of self-acceptance and life.Reference Fonseca, Cunha, Faria, Campos and Queirós38

According to Alghamdi, et al,Reference Alghamdi, Hunt and Thomas20 emergency personnel presented passive coping strategies such as behavioral disconnection, substance abuse, and self-blame, but showed significant positive changes after the use of narrative exposure therapy.

Additionally, it was reported that nonadaptive strategies that are related to a behavioral disconnection from stressful situations and a feeling of loss of control do not allow people to resort to active strategies to cope with problems.Reference Clohessy and Ehlers27,Reference Moskola, Sándor and Susánszky31

The nonadaptive coping strategies used by these personnel showed a strong relationship with PTSD symptoms, burnout syndrome, psychiatric morbidity, and chronic stress, specifically avoidance coping. The importance of these studies performing correlations with psychiatric symptoms was conclusive evidence with respect to the adaptability of these coping styles.

Adaptive Coping Strategies

These types of strategies were presented less frequently among these personnel, but they are significant in cushioning the adverse effects of continuous exposure to trauma. Strategies that involve active coping as behaviors aimed at resolving such situations can minimize the negative effects of the experience. Among these active coping strategies, the authors reported acceptance as a strategy in which both the situation faced and the emotions generated from it are recognized and accepted, solutions to resolve them are sought, and the stressful event is interpreted in a positive way based on the deliberate reflection of trying to understand the trauma, reflective and constructive thoughts, valuing the traumatic event as an experience of growth and learning, and interpreting it as rewarding.Reference Miller and Brown18,Reference Iwasaki, Mannell, Smale and Butcher39–Reference Völker and Flohr-Devaud41 Acceptance is an important component in building resilience.Reference Demiroz and Haase48 In this sense, Chang, et alReference Chang, Lee, Connor, Davidson and Lai45 and Clohessy, et alReference Clohessy and Ehlers27 reported positive reinterpretation as another important strategy that seeks the positive in the situation to improve and grow from it, promote well-being, and decrease anxiety and stress.

For Moskola, et al;Reference Moskola, Sándor and Susánszky31 Sattler, et al;Reference Sattler, Boyd and Kirsch42 Yang, et al;Reference Yang and Ha43 Durham, et al;Reference Durham, McCammon and Allison28 Vaulerin, et al;Reference Vaulerin, D’Arripe-Longueville, Emile and Colson47 Oginska-Bulik, et al;Reference Oginska-Bulik and Langer46 and Witt, et al,Reference Witt, Stelcer and Czarnecka-Iwańczuk24 coping focused on addressing situation and seeking to resolve the internal or environmental demands that were generated by the stressful event. This is accomplished through meetings in which staff are exposed to psychological debriefing, impressions are explored, facts, thoughts, and emotions are reviewed, and education is provided on how to deal with stress, with the objective of taking action and making an effort to resolve the situation through cognitive transformation.Reference Scott, O’Curry and Mastroyannopoulou49 Establishing this type of coping is a protective factor for staff.

Self-efficacy, as a coping strategy, determined by the competence and personal capacity to face stressful situations and regulate one’s own functioning, is another of the protective strategies that help control thoughts and regulate emotions in these staff.Reference Soravia, Schwab, Walther and Müller22

Other strategies that alleviate the symptoms were emotional support either as social support given by coworkers, bosses, or institutions and the instrumental support given by specialized mental health personnel. This support from peers, family, friends, or experts and talking about what happened after the incidents was associated with a key mechanism for the management of emotions and the ability to cope with trauma.Reference Almutairi and Azza19,Reference Lee, Park and Sim23,Reference Minnie, Goodman and Wallis32,Reference Boland, Mink, Kamrud, Jeruzal and Stevens33,Reference Pisarski, Bohle and Callan35,Reference Shakespeare-Finch, Smith and Trauma36,Reference Chang, Lee, Connor, Davidson and Lai45

Discussion

Health professionals in general experience stress associated with care work, and it is a frequent and globalized experience.Reference Kucmin, Kucmin, Turska, Turski and Nogalski25,Reference Yang and Ha43 It is well-documented by the international literature that health personnel who attend emergencies in the prehospital setting are exposed to higher levels of stress than that of other health professionals.

Although the literature reviewed contains a variety of classifications of coping strategies (eg, focused on emotion, the problem, passive and active, negative and positive, or dysfunctional) and tools that are validated and adjusted for this objective, approaches can be different, which makes the analysis and the unification of concepts complex. However, a simple classification that encompasses all of these strategies is to characterize them as adaptive and nonadaptive,Reference Echeburúa and Amor11 which addresses the impact that each of these has on the mental health of the studied personnel.

Of the questionnaires used, several authors have redesigned, revised, and provided evidence of validity on tests to adapt them to sociocultural contexts to which they would be applied. Hence, there are versions of instruments adapted to the Arabic, Chinese, Portuguese, Polish, and Greek languages, and culture, among others.

The strategies used by these first responders have allowed them to cope with exhaustion, PTSD, other psychiatric conditions, and even the risk of musculoskeletal injuries.Reference Vaulerin, D’Arripe-Longueville, Emile and Colson47 Forty-two percent of the studies reviewed related nonadaptive coping to PTSD, which resulted from experiencing the stress of extreme traumatic intensity.Reference Kucmin, Kucmin, Turska, Turski and Nogalski25

In a 2018 meta-analysis, Petrie, et alReference Petrie, Milligan-Saville and Gayed50 reported an 11% prevalence of PTSD among ambulance personnel, which is similar to that reported in this review. Acuña, et alReference Acuña Conejero, Aguado Márquez, Álvarez Casado and Amores Tola51 in a systematic review in 2021 reported a causal relationship between PTSD and emergency workers, describing risk factors for the worsening of PTSD, such as female sex, diagnosis of anxiety, and chronic depression and substance abuse. In the male population evaluated, nonadaptive strategies were related to PTSD. In 2021, Brooks, et alReference Brooks and Brooks52 determined that coping strategies were among the factors involved in the development of PTSD symptoms.

In a 2018 study by Arble, et al,Reference Arble, Daugherty and Arnetz53 the coping strategies of a group of police officers were evaluated as part of the group of professionals called first responders, which also included firefighters, rescuers, and ambulance personnel. They found that those who used coping based on adaptive coping had greater well-being and posttraumatic growth. They also reported the use of avoidant coping (nonadaptive) as one of the most used strategies by this study group and found similarities in coping behavior with other first-responder occupations. These findings are similar to those of the studies analyzed in this research.

To help understand the coping processes, authors such as Stępka-Tykwińska, et alReference Stępka-Tykwińska, Basińska, Sołtys and Piórowska54 in 2019 and Borzyszkowska, et alReference Borzyszkowska and Basińska55 in 2020 introduced the term coping flexibility, defined as the ability to continuously search for better and more effective solutions to stress, which reflects the willingness of the individual to use different strategies to meet the demands of changing circumstances; their findings agree with those of this systematic review and studies such as Di Nota, et alReference Di Nota, Kasurak, Bahji, Groll and Anderson56 in 2021 and Warren-James, et alReference Warren-James, Dodd, Perera, Clegg and Stallman57 in 2022 which recommended effectively promoting adaptive coping for public security personnel to mitigate posttraumatic stress injury by offering training programs with the objective of establishing psychological well-being among these personnel.

Finally, one of the adaptive strategies that facilitates improving the ability to face stressful situations and moderate the impact of stress is social support. DonovanReference Donovan58 found that peer support and support from their employers helps first responders with the processing of traumatic events and experiencing greater well-being and posttraumatic growth. This adaptive strategy was the most reported in the studies evaluated in this review.

Strengths

As strengths, this systematic review describes the types of coping strategies used by first responders to emergencies and how these strategies are related to mental disorders. These affect the general and psychological health of the health personnel in this setting. Consequently, as a prevalent and global situation, these results serve as an element of analysis to set preventive measures, and coordinate support programs to improve the mental health of those who work in this area and who suffer its consequences. In addition, all staff need to be educated in using adaptive strategies and in coping flexibility to reduce the harmful effect on the first responders to emergencies.

Limitations

As a limitation, the cross-sectional design found in almost all the studies does not allow determining a causal association. They only suggest a relationship.

Longitudinal studies are required to determine causal effects.

Conclusions

The coping strategies most used by first responders to emergencies were maladaptive ones, specifically avoidance, avoiding recurring feelings and thoughts about the events they faced, generated psychological tension and the development of mental disorders.

Learning to develop adaptive coping strategies, whether focused on problems or seeking emotional support, can benefit emergency personnel and help them cope with stressful situations. These coping strategies should be strengthened to help prevent people from experiencing long-term negative effects that could arise from the traumatic events to which they are exposed, promoting the ability to choose coping strategies focused on the problem instead of avoidance strategies.

Institutions must ensure that first responders have access to emotional support groups, either social or instrumental, after critical incidents and the implementation of active coping strategies shortly after potentially traumatic events.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare none.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049023X22001479