Introduction

Hypo- and hyperventilation commonly occur in the early post-injury period. Among patients with perfusion-sensitive conditions and traumatic brain injury (TBI), altered ventilation patterns can adversely impact short- and long-term outcomes. Reference Caulfield, Dutton, Floccare, Stansbury and Scalea1,Reference Warner, Cuschieri, Copass, Jurkovich and Bulger2 Hyperventilation reduces cerebral blood volume by inducing hypocarbia with the resultant effects of cerebral vasoconstriction and decreased intracerebral pressure (ICP). Reference Chestnut, Marshall and Klauber3,Reference Raichle and Plum4 Hyperventilation can also decrease intracranial pH, which reduces lactic acidosis. Reference Lassen5,Reference Muizelaar, Marmarou and Ward6 Although hyperventilation may be beneficial in select patients with TBI, the decrease in cerebral blood flow produced by hyperventilation impairs normal blood flow, especially among patients with diffuse cerebral edema. Reference Bouma, Muizelaar, Choi, Newlon and Young7–Reference Marion, Darby and Yonas9 For these reasons, the Brain Trauma Foundation (New York, New York USA) guidelines include a recommendation for maintaining normocarbia (end-tidal carbon dioxide [ETCO2] between 35-40mmHg) and avoiding hyperventilation (ETCO2 <35mmHg), except in the presence of imminent signs of cerebral herniation. Reference Carney, Totten and O’Reilly10

Outcomes after TBI are not only determined by the severity of anatomic injury, but also by the severity of secondary injury related to management in the prehospital setting and initial emergency department phases of care. Reference Chestnut, Marshall and Klauber3 Hypoxia and hypotension in the prehospital setting can contribute to secondary brain injury and worsen morbidity and mortality. Strategies for avoiding these derangements have been shown to improve patient outcomes. Reference Davis, Peay and Serrano11–Reference Lewis13 Previous studies have included patients treated in prehospital settings, emergency departments, and intensive care units (ICUs). Combining patients in these variable settings makes it more difficult to define early ventilation management strategies. The impact on mortality of maintaining normocarbia in the initial resuscitation phase is unknown. To address this gap, this systematic review assessed the best evidence-based practice of ventilation management during the initial trauma resuscitation period.

Methods

Study Design

This systematic review examined the association between ventilation during the initial post-injury and resuscitation phase and outcomes in pediatric and adult trauma patients. Studies published in English that evaluated trauma patients in the prehospital or emergency department settings were included. This systematic review is registered in the PROSPERO International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (ID number: 178676) and conforms to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) reporting guidelines and checklist. 14,Reference Moher, Shamseer and Clarke15

Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

To initiate the development of search terms, four index articles addressing the association between ventilation and outcomes of trauma patients were identified. The index articles reported that hyperventilation during the early resuscitation phase was associated with increased mortality in patients with TBI. Reference Warner, Cuschieri, Copass, Jurkovich and Bulger2,Reference Davis, Dunford, Poste, Ochs, Holbrook and Fortlage16–Reference Dumont, Visioni, Rughani, Tranmer and Crookes18 The search strategy incorporated MESH terms from these index articles. Search terms related to injury (eg, traumatic, injuries, wound, or brain injury), ventilation (eg, hypoxia and hyper/hypocapnia), and location of care (eg, prehospital, trauma bay, or emergency room) were included (Appendix 1; available online only). The literature search for studies published after 2008 used a combination of standardized terms and keywords in PubMed (National Center for Biotechnology Information, National Institutes of Health; Bethesda, Maryland USA), CINAHL (EBSCO Information Services; Ipswich, Massachusetts USA), and SCOPUS (Elsevier; Amsterdam, Netherlands) databases (Appendix 2; available online only). To account for the most up-to-date trauma management guidelines, only studies published after 2008 were included in the review. Additional keyword searches were run in Google Scholar (Google Inc.; Mountain View, California USA). All searches were conducted in November 2019. Following de-duplication of sources in Endnote (Clarivate Analytics; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania USA), the Rayyan QCRI systematic review application (Rayyan Systems Inc.; Cambridge, Massachusetts USA) was used for source management and evaluation at the abstract level. Reference Ouzzani, Hammady, Fedorowicz and Elmagarmid19

Two teams reviewed the abstracts. Each team included a pediatric emergency medicine fellow, a surgical resident, and a pediatric resident. Abstracts were randomly assigned to each team. Abstract review was conducted using pre-defined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Studies eligible for inclusion were those evaluating the association between ventilation of trauma patients in the prehospital or emergency department settings and any morbidity or mortality following injury. Studies with a focus on either pediatric or adult patients were also eligible for inclusion. Studies that assessed ventilation monitoring or ventilation management following the initial resuscitation (eg, in-patient floor, ICU, or operating room) were excluded. Case studies and reports were also excluded at the abstract level. Abstracts with majority approval within each team were advanced to full-text review. The six reviewers independently analyzed each full-text and voted on inclusion using the same criteria from abstract selection. Texts that received four or more votes of approval were included in the systematic review. This multiple person method for full-text paper selection, followed by confirmation with the two senior writers, established quality control.

Data Extraction

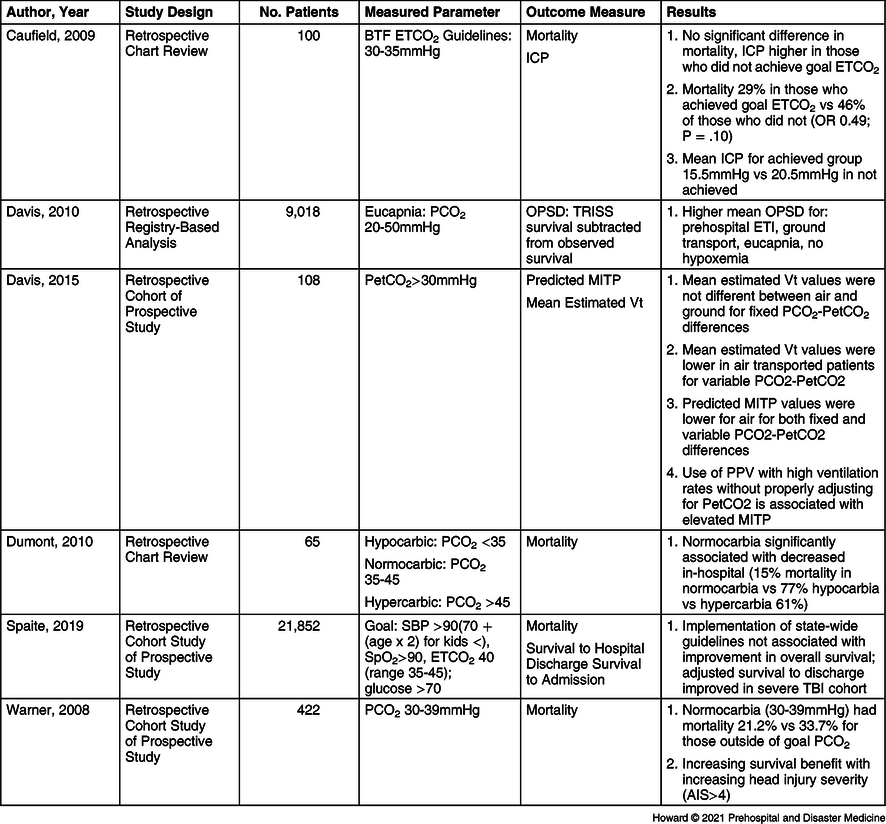

After reaching consensus on the studies for inclusion in the systematic review, two reviewers independently extracted data from each study. Data that were extracted included: study design, time period of analysis, study inclusion and exclusion criteria, number of patients, age ranges, measured parameter of ventilation and the standard to which it was compared, outcomes, and timing of outcomes related to the measured ventilation parameter (Table 1).

Table 1. Articles Included in the Systematic Review

Abbreviations: BTF, Brain Trauma Foundation; ETCO2, end tidal carbon dioxide; PCO2, partial pressure of carbon dioxide; OPSD, observed-predicted survival difference; TRISS, Trauma Score and Injury Severity Score; ETI, endotracheal intubation; PetCO2, end tidal carbon dioxide; MITP, mean intrathoracic pressure; Vt, tidal volume; PPV, positive pressure ventilation; SBP, systolic blood pressure; SpO2, oxygen saturation; TBI, traumatic brain injury; AIS, abbreviated injury score.

Results

Search Results

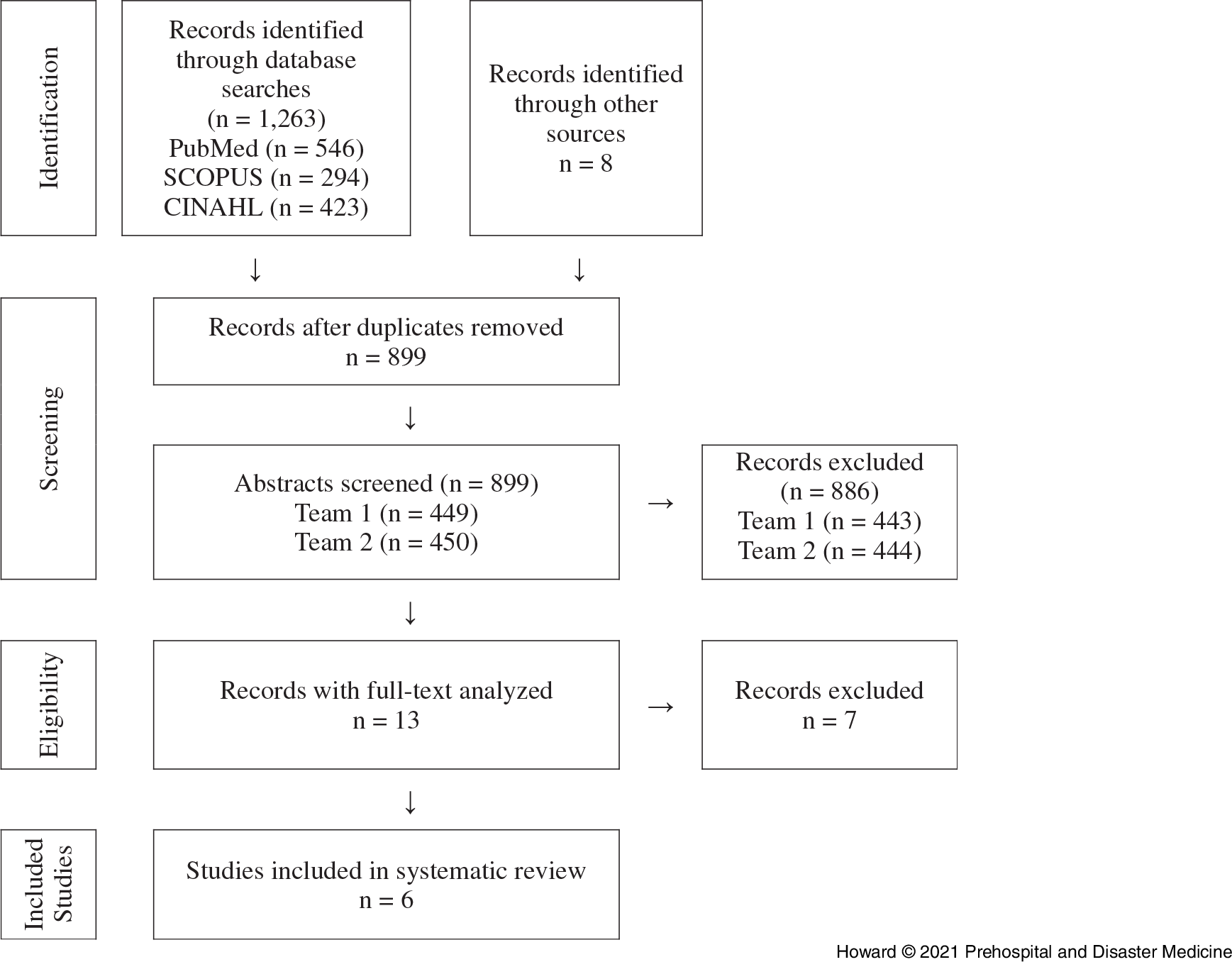

The initial search yielded 891 articles following de-duplication of the database searches and eight articles from additional sources (Figure 1). Thirteen abstracts were relevant and identified for full-text review. Among the studies that underwent full-text review, two were excluded due to methodology (review) and five because the reported findings did not include measures of ventilation (eg, focus on hypoxemia, Glasgow Coma Scale [GCS], or mortality). Six full-text articles met criteria for inclusion in the final review (Table 1). Reference Caulfield, Dutton, Floccare, Stansbury and Scalea1,Reference Warner, Cuschieri, Copass, Jurkovich and Bulger17,Reference Dumont, Visioni, Rughani, Tranmer and Crookes18,Reference Davis, Peay and Sise20–Reference Spaite, Bobrow and Keim22

Figure 1. PRISMA Diagram Showing Selection of Articles for Review.

Abbreviation: PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

Description of Included Studies

All studies included in the systematic review were retrospective cohort or chart reviews. Three were retrospective secondary analyses of prospectively collected data, while the other three were retrospective analyses of registry or medical record data. Reference Caulfield, Dutton, Floccare, Stansbury and Scalea1,Reference Warner, Cuschieri, Copass, Jurkovich and Bulger17,Reference Dumont, Visioni, Rughani, Tranmer and Crookes18,Reference Davis, Peay and Sise20–Reference Spaite, Bobrow and Keim22 Study populations varied from 65 to 21,852 patients treated during study periods that ranged from two to 16 years (median length seven years). Two of the six studies included pediatric trauma patients. Reference Warner, Cuschieri, Copass, Jurkovich and Bulger17,Reference Spaite, Bobrow and Keim22 In one study, three percent of patients were younger than 14 years of age. Reference Warner, Cuschieri, Copass, Jurkovich and Bulger17 The specific number of children was not specified in the second study. Reference Spaite, Bobrow and Keim22

Although the studies all had different aims and thus collected different types of data, all studies evaluated the ventilatory management of patients with TBI in the initial resuscitation phase. Each evaluated measures of ventilation in the prehospital setting. One study investigated compliance with recommended parameters for ETCO2 measurements. Reference Caulfield, Dutton, Floccare, Stansbury and Scalea1 A second study reported the impact of implementing a protocol for Emergency Medical Services that included guidelines for monitoring ETCO2 in addition to maintaining normal oxygenation, systolic blood pressure, and glucose. Reference Spaite, Bobrow and Keim22 A third study addressed prehospital intubation and the association with observed and predicted outcomes among TBI patients. Reference Davis, Peay and Sise20 A fourth study included predicted mean intrathoracic pressure values based on measures of ventilation in the prehospital setting. Reference Davis, Aguilar and Smith21 The remaining two studies evaluated prehospital partial pressure carbon dioxide (PCO2) in relationship to hospital mortality. Reference Warner, Cuschieri, Copass, Jurkovich and Bulger17,Reference Davis, Peay and Sise20

The most frequently measured parameters related to ventilation were ETCO2 or PCO2. Four studies reported mortality as an outcome. Reference Caulfield, Dutton, Floccare, Stansbury and Scalea1,Reference Warner, Cuschieri, Copass, Jurkovich and Bulger17,Reference Dumont, Visioni, Rughani, Tranmer and Crookes18,Reference Spaite, Bobrow and Keim22 One study included predicted survival difference as an outcome, and another included calculations of mean intrathoracic pressure and estimated tidal volumes. Reference Davis, Peay and Sise20,Reference Davis, Aguilar and Smith21 Two studies assessed the association between normocarbia and decreased mortality, but cited small sample sizes as limitations. Reference Caulfield, Dutton, Floccare, Stansbury and Scalea1,Reference Davis, Peay and Sise20

Outcomes

Mortality was reported in four of the six studies. Reference Caulfield, Dutton, Floccare, Stansbury and Scalea1,Reference Warner, Cuschieri, Copass, Jurkovich and Bulger17,Reference Dumont, Visioni, Rughani, Tranmer and Crookes18,Reference Davis, Peay and Sise20 These studies defined mortality as failure to survive to hospital discharge. Reference Caulfield, Dutton, Floccare, Stansbury and Scalea1,Reference Warner, Cuschieri, Copass, Jurkovich and Bulger17,Reference Dumont, Visioni, Rughani, Tranmer and Crookes18,Reference Spaite, Bobrow and Keim22 Two studies also evaluated survival to hospital admission. Reference Caulfield, Dutton, Floccare, Stansbury and Scalea1,Reference Spaite, Bobrow and Keim22 Patients with a normal ETCO2 or PCO2 upon arrival to the hospital had lower mortality. Reference Caulfield, Dutton, Floccare, Stansbury and Scalea1,Reference Warner, Cuschieri, Copass, Jurkovich and Bulger17,Reference Dumont, Visioni, Rughani, Tranmer and Crookes18 In one study, patients who achieved a prehospital ETCO2 goal of >29mmHg had lower odds of mortality compared to those who did not (29% versus 46%, OR = 0.49 [95% CI, 0.21-1.1]). Reference Caulfield, Dutton, Floccare, Stansbury and Scalea1 In another study, patients with normocarbia (PCO2 35-45mmHg) on presentation had a 15% reduction in hospital mortality compared to those presenting with hypocarbia (hospital mortality 77%) or hypercarbia (hospital mortality 61%; P <.05). Reference Dumont, Visioni, Rughani, Tranmer and Crookes18 Another study reported lower rates of mortality among patients whose ETCO2 was within a target range of 30-39mmHg on arrival compared to those with ETCO2 outside of the range (16.2% versus 23.9%; P = .06). Reference Warner, Cuschieri, Copass, Jurkovich and Bulger17

Three of the six studies reported additional effects of ventilation. One study evaluated the impact of implementing a prehospital TBI ventilation guideline and reported contrary results. Before guideline implementation, a lower mortality rate was observed among patients who did not achieve an EtCO2 of 35-45mmHg compared to the post-implementation group that achieved this target (13.4% pre-intervention versus 15.1% post-intervention; P <.001). The authors proposed that their findings may have been impacted by a higher frequency of older patients and more severe injury in the post-implementation group. Reference Spaite, Bobrow and Keim22 When stratified by severity, the findings favored guideline implementation for the most severely injured patients. Their reported post-implementation adjusted survival to hospital admission was approximately two-fold higher among patients with severe TBI and three-fold higher for those with severe TBI who had received positive pressure ventilation or endotracheal intubation. The authors attributed these findings to compliance with the guidelines supporting oxygenation/preoxygenation and avoiding hyperventilation. Reference Spaite, Bobrow and Keim22 In the second study, the mean observed predicted survival was the primary outcome. Reference Davis, Aguilar and Smith21 The authors calculated a prehospital mean observed predicted survival differential for ventilation by subtracting the probability of survival predicated by the trauma score and injury severity score from observed survival. They found odds of survival more favorable among intubated patients with hypocapnia or eucapnia compared to hypercapnia. The third study evaluated adjustment for ETCO2 during the delivery of positive pressure ventilation with high ventilation rates to maintain appropriate mean intrathoracic pressures. Based on cardiac arrest physiology models, the authors postulated that elevated mean intrathoracic pressures may worsen venous return and cardiac output in hemodynamically unstable patients. Reference Davis, Aguilar and Smith21

Discussion

The results of this systematic review favor normoventilation in the prehospital and emergency department settings and report this ventilation strategy with improved mortality following TBI. These results are consistent with other systematic reviews with broader criteria that included evaluation of ventilation after the initial resuscitation phase. Reference Caulfield, Dutton, Floccare, Stansbury and Scalea1,Reference Brandi, Stocchetti, Pagnamenta, Stretti, Steiger and Klinzing23,Reference Asehnoune, Roquilly and Cinotti24 This review focused on studies addressing ventilation during initial resuscitation to define early interventions available in these settings rather than those relying on enhanced monitoring and later stage management of TBI. Establishing best practices that can be implemented during the “golden hour,” from scene transport to initial emergency department management, is needed to define best practice for optimal patient outcomes. Reference Boyd and Colwy25

While all studies included patients who had sustained TBI, the measures of severity differed, including GCS, head injury severity score, Abbreviated Injury Score, or Trauma Injury Severity Score. The primary outcomes of the included studies also varied, with different study settings, methodologies, and evaluated predictors and outcomes. All studies evaluated ventilation and mortality in a cohort of patients with TBI. Methods of ventilation (endotracheal intubation/bag-valve mask) and ventilation parameters, such as respiratory rate, tidal volume, and mean intrathoracic pressure, were not consistently examined. While mean intrathoracic pressure was not directly measurable, increased intrathoracic pressure resulting from hyperventilation can negatively impact hemodynamics during resuscitation. Reference Aufderheide, Sigurdsson and Pirrallo26,Reference Pepe, Lurie, Wigginton, Raedler and Idris27 All studies assessed the effect of either ETCO2 or PCO2 on mortality. None of the studies controlled for the effects of in-patient care on hospital mortality.

Respiratory support requirements and the monitoring modalities for providing this support vary among trauma patients. The metrics used in the included studies are feasible in most prehospital environments. In the prehospital setting, ETCO2 monitoring is an accurate and accessible method of monitoring ventilation and can guide post-intubation ventilation from the field to the hospital. Reference Kodali and Urman28–Reference Childress, Arnold, Hunter, Ralls, Papa and Silvestri30 Monitoring ETCO2 can be delegated to any member of the team. Based on the data summarized in this review, establishing normoventilation with early ETCO2/PCO2 monitoring can improve outcomes after TBI. Reference Caulfield, Dutton, Floccare, Stansbury and Scalea1,Reference Warner, Cuschieri, Copass, Jurkovich and Bulger17,Reference Dumont, Visioni, Rughani, Tranmer and Crookes18,Reference Davis, Peay and Sise20–Reference Spaite, Bobrow and Keim22 While a randomized control trial is needed to verify the effects of ventilation on outcomes, the detrimental effects of hypo- and hyperventilation suggested by these studies make this type of trial ethically challenging to implement. A large, prospective study assessing ventilation during initial resuscitation and its effects outcomes is a suitable proxy. Translation of findings from future studies can give guidance to the development of evidence-based practices and promote the delivery of the safest, highest quality care.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the search strategy included three relevant databases but limited the search to studies published after 2008. Although a focus on ventilation in trauma management is not novel, a better understanding of physiology and guidelines for normoventilation, with an ETCO2 goal between 35-45mmHg, has been a relatively new focus supporting this restriction. Reference Chestnut, Marshall and Klauber3,Reference Coles, Fryer and Smielewski8,Reference Carney, Totten and O’Reilly10 Second, the database search only included publications in English and was guided by general trauma-related search terms. In addition to potential papers published in other languages, the search may have missed other publications because of the lack of a uniform terminology for describing ventilation quality. Third, although the intent was to identify studies relevant to all types of injury, all articles meeting inclusion criteria focused on TBI. Articles related to other types of injury and the effects of ventilation on outcomes could not be identified. Fourth, the main outcome focus for this review was limited to mortality, but analysis of additional outcomes such as hospital length of stay, long-term disability, and other morbidity measures could provide additional insight into the impact of ventilation. Finally, the search and inclusion criteria only identified a small set of papers to review. This review was able to identify clinically relevant findings, but additional research is needed to guide practice changes that are necessary for optimal patient outcomes. These findings highlight two major features that these studies should include: (1) a range of injury mechanisms and severity metrics, and (2) adjustment of mortality for hospital-based treatment.

Conclusions

The results of this systematic review show that normoventilation during the early stages of trauma resuscitation of patients with TBI is associated with decreased mortality following injury. Standardization of ventilation monitoring during trauma resuscitation has the potential to improve outcomes for patients with TBI. This systematic review supports the need for prospective, trauma-specific investigations to determine the safest ventilation strategies during the early phases of trauma resuscitation that improve patient mortality.

Conflicts of interest/funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health: award number R01LM011834. The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author Contributions

MBH, NLM conceptualized and designed the study, contributed to methodology and investigation, supervised and oversaw literature review, drafted the initial manuscript, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. ECA conceptualized and designed the study, contributed to the methodology and investigation, performed literature review, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. HK, MEM, LT contributed to literature review and reviewed and revised the final manuscript. SK developed literature search strategy and terms, and reviewed and revised the final manuscript. IM, AS conceptualized and designed the study, acquired funding, and reviewed and revised the final manuscript. RSB, KJO conceptualized and designed the study, acquired funding, contributed to the methodology and investigation, oversaw literature review, and reviewed and revised the final manuscript.

All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work. KJO takes responsibility for the manuscript as a whole.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049023X21000534