Introduction

As one of the most articulate expressions of history, culture and community, African American gospel music seems without obvious parallel as a musical and social phenomenon of the twentieth century. Furthermore, researchers are beginning to now credit African American gospel music as being one of the key underpinning influences in the development of the juggernaught that has become contemporary popular music throughout the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. Reagon (Reference Reagon1992) lends substantial support to this notion when she states:

Today, it is African American music, in structure and often in content, that drives mainstream popular music worldwide … the way the voice is used, the way the instruments are held and played, the way the instruments sound when played, the way an audience responds in a contemporary concert, the way in which a performer has dialogue with the audience, all can be traced to the African American worship tradition created within the Black church. (Reagon Reference Reagon1992, pp. 3–4)

African American gospel music is a powerful musical and ‘spiritual’ expression that is to a larger extent defined by the musical style and performance practices of one of its central figures; the gospel singer. Reagon writes that ‘Gospel is both a repertoire and a style of singing’ (Reagon Reference Reagon1992, p. 5), underlining the dynamic inter-relationship between gospel music and the performance practices of the gospel singing style, and Boyer categorically states that ‘so great were these [gospel singing] practices that by the mid-1940's they defined gospel style’ (Boyer Reference Boyer2000, p. 49).

Singing a form of ‘sacred blues’, a genre pioneered by gospel's founding father Thomas Dorsey, the musical and physical performance styles of the African American gospel singer and the complexity of nuance, gesture and the deeply expressive quality contained within their unique vocal styles, becomes definitive of the broader African American gospel music genre. Writers and researchers of African American gospel music have for some time applied now-familiar descriptors to the various gospel singing practices and techniques (‘gravel’, ‘slides’, ‘wails’, ‘screams’ and ‘shouts’) that constitute the African American gospel singing style. However, in clearly defined musical terms, the effectiveness of these descriptors when employed outside of their originating culture is quite limited, lacking in precise definition and therefore problematic to apply with any accuracy to scholarly research.

The purpose of this paper therefore is firstly to define and annotate some of the key descriptive terms commonly applied to African American gospel singing techniques in order that greater consistency and clarity can be achieved in relation to their usage within contemporary popular music research. The basis for this research grew out of the author's direction of the award-winning Australian ensemble, The Southern Gospel Choir, and the subsequent development of his Ph.D. thesis (The Transculturalisation of African American Gospel Music; the Context and Culture of Gospel Traditions in Australian Gospel Music), which in part examined the author's methodologies and techniques for teaching contemporary African American gospel music within an Australian context. As a result, this paper further seeks to introduce an analytical notational system, accompanied by a series of annotated musical transcriptions, that forms the basis of the author's taxonomy of musical gesture for African American gospel music, and which may provide a framework for comparative analytical research within the field of gospel-inspired contemporary popular music (refer to Taxonomy at end of paper).

Figure. The Australian Recording Industry Awards nominated Southern Gospel Choir, directed by Andrew Legg, perform at the University of Tasmania's Stanley Burbury Theatre (photo by Dean Stevenson).

Foundational gospel singing techniques

Williams-Jones (Reference Williams-Jones1975) identifies the following six African American gospel vocal techniques that she extrapolated from a performance of Peace Be Still by James Cleveland. They are as follows:

(1) Moans

(2) Grunts

(3) Wails

(4) Shouts

(5) Gliding Pitches

(6) Song Speech

Boyer (Reference Boyer1979) further identified eight key gospel singing attributes and techniques that he extrapolated from a performance by Clara Ward from the Ward Singers' seminal 1949 recording of the W.H. Brewster gospel song, Surely God is Able:

(1) Vocal timbre

(2) ‘Gospel’ vibrato

(3) Melodic ornamentation

(i) Ascending and descending passing tones

(ii) The bend

(iii) Upper and lower neighbour tones

(iv) The gruppetto

(v) The portamento

(4) Rhythmic improvisation

(5) Textual interpolation (expansion and personalisation)

Subsequent to Ward's performance on the original recording, Boyer (Reference Boyer2000) later identified the following additional gospel vocal techniques:

(1) Simultaneous improvisation

(2) Development of the ‘high who’ between choruses/sections

(3) Rhyming or ‘wandering’ couplets/quatrains

Based on these musical and expressive techniques and descriptors, it is possible to develop a definitive taxonomy of essential gospel vocal techniques (see Table 1). For the purposes of this article, discussion and analysis will focus on only three specific areas from this taxonomy; firstly, the African American gospel ‘moan’ and then a variety of other specific techniques employed by African American gospel singers in their use and manipulation of timbre and pitch.

Table 1. Essential gospel singing techniques.

The gospel moan

Southern (Reference Southern1997) quotes Paul Svin'in, a Russian traveller and visitor to Bethel church in 1811, who described one of the musical practices he observed as an ‘agonizing, heart-rending moaning’ (p. 79). Moaning may use a simple or not discernable text; however, it is nevertheless laden with emotion and meaning, containing a resonance that is far more than purely physical sound. The moan has an expressive quality that is multifaceted, dependent on context and performer, ranging from a closed mouth sound resonating through the nasal passage to an open-throated, open-mouthed, louder and more resonant moan of unspecified pitch that is more akin to a cry of physical pain. Some of the earliest examples of the ‘moan’ can be heard in the Afro-American Spirituals, Work Song, and Ballads field recordings, and one of these recordings, ‘Aint No More Cane’ illustrates an open-vowel moan, punctuating the verse lines with the sound ‘Oh–o’ (Example 1 and Taxonomy 10, 12, 14).

Example 1. Moan A: Ernest Williams, ‘Ain't No More Cane’ (Tax. 10, 12, 14) (CD 1510; 1998). *All transcribed examples are taken from specific recordings, and which are noted in the discography.

Mahalia Jackson employs a simple moan in her recording ‘The Upper Room’ (Example 2, bar 3). This moan bears the emotion of the ‘mother's tone’ (a characteristic of Jackson's performances), and is a positive and reassuring sound, that also functions in this song as a punctuation point separating the colla voce opening from the metered tempo section that follows Example 2, and later the reiteration of the refrain (see Example 3). Aretha Franklin employs this same closed-mouth technique over an extended phrase length, in the opening of ‘Amazing Grace’, recorded in 1972 with James Cleveland (see Example 4).

Example 2. Moan B: Mahalia Jackson, ‘The Upper Room’ (Tax. 10, 14, 22, 23) (R2 CD-40-39/1; 2001).

Example 3. Moan C: Mahalia Jackson, ‘The Upper Room’ (Tax. 14, 23).

Example 4. Moan D: Aretha Franklin, ‘Amazing Grace’ (Tax. 7, 10, 20) (R2 75627; 1999).

The moan can also take the form of an open-mouthed ‘cry from the heart’, revealing a deep-rooted sense of pain and suffering. Bars five through eight (Example 5) illustrate this, where the sound ‘Oh’ in the text ‘Oh Lord’ and ‘O Lordy’ functions also as an open-mouthed, open-throated moan, conveying a more powerful emotion than the sound might initially suggest. Werner (Reference Werner2006) highlights the moan as an expression of deep-felt pain and suffering in his description of the ‘deep gospel moan’ produced by soul singer Tina Turner in ‘A Fool in Love’. Werner maintains that it is Turner's troubled life that underpins her use of a scream-like, open-mouthed ‘moan’ which she produces at the beginning of the song, and which Werner closely aligns with the physical and emotional pain that Turner experienced during her life.

Almost every female singer of the early sixties had, at the very least, suffered through a series of difficult romantic relationships. Tina Turner accepted Ike [Turners beatings] in part because she preferred them to life in the cotton fields where she had grown up … Ike may have provided an alternative to Nutbush, Tennessee, where Tina grew up as Anna Mae Bullock, but the price of the ticket was high. You can hear it in Tina's voice on ‘A Fool in Love’. (Werner Reference Werner2006, p. 38)

Turner's rhythm & blues/soul singing is steeped in the gospel tradition, and the moan, whilst more aggressive, is still clearly present as Example 6 illustrates.

Example 5. Moan E: Dora Reed, Henry Reed and Vera Hall, ‘Trouble So Hard’ (Tax. 14) (1510; 1998).

Example 6. Moan F: Tina Turner, ‘A Fool in Love’ (Tax. 1, 2, 3, 6, 16).

Incidentally, the moan is still used in contemporary gospel, predominantly adhering to the more aggressive approach evident in the Turner example. ‘I'm Blessed’ (Example 7) recorded in 1996 by the National Baptist Convention Mass Choir with the featured soloist, Paul Porter, also uses the moan as part of his colla voce introduction.

Example 7. Moan G: Paul Porter, ‘I'm Blessed’ (Tax. 1, 3, 6, 10, 11, 29) (51416-5240-2; 1996).

Finally, contemporary gospel artist Fred Hammond takes the feeling of the traditional moan and places it in a contemporary gospel context (Example 8), writing it into the vocal ensemble parts as well as his own soaring, quasi-improvised solo line, fusing African American gospel with elements of contemporary popular music.

Werner (Reference Werner2006) states that; ‘The gospel singer testifies to the burden and the power of the spirit in moans or screams or harmonies so sweet they make you cry’. The moan therefore could be seen as an articulate expression of a deep, communal understanding and acknowledgement of pain, suffering, and perseverance under trial, that transcends the written, or sung, word.

Example 8. Moan H: Fred Hammond, ‘My Heart is For You’ (Tax. 8, 10) (82876-86952-9; 2006).

Timbre

Gravel and grunts

In most traditional [African and African American] singing there is no apparent striving for the ‘smooth’ and ‘sweet’ qualities that are so highly regarded in Western tradition. Some outstanding blues, gospel, and jazz singers have voices that may be described as foggy, hoarse, rough or sandy. Not only is this kind of voice not derogated, it often seems to be valued. Sermons preached in this type of voice appear to create a special emotional tension (Courlander Reference Courlander1991, p 23).

The tonal characteristics of the African American gospel ‘voice’ are as rich and as varied as the number of singers. The ‘gravel’ in the voice (alternatively referred to as ‘rasp’ ‘grit’ or ‘hoarseness’) used by many singers is a commonly applied general vocal characteristic that also functions as a means of creating an impassioned emphasis and added intensity to a word or phrase. Kirvy Brown, soloist with the Love Fellowship Tabernacle Choir, illustrates this technique in a contemporary gospel song, ‘Lord Do It’. She begins with a more open, purer tone, building intensity with the gravel tone on key lyrics (Example 9), to a final climactic and dramatic conclusion to the verse in full voice gravel that becomes an imploring scream (Example 10). Fred Hammond also employs this technique in an ‘impromptu’ medley of traditional African American gospel tunes on his live DVD Speak Those Things: POL Chapter 3 (Hammond 2007). Within the context of a contemporary gospel concert, Hammond switches from a lyric tenor, ‘pop’ oriented vocal style to a gravel-toned emphatic vocal style reminiscent of the gospel singers – and preachers – of the past (Example 11), particularly with the phrase ‘Let me see you clap your hands, stand up on your day’ (Example 12). Hammond uses the gravel tone to add a significant emphasis to both the text and his choice of song, emphasising a strong connection to his gospel heritage and the practice of ‘moving the house’, and by engaging the community (audience) in the performance itself.

Example 9. Gravel A: Kirvy Brown, ‘Lord Do It’ (Tax. 1, 2, 3) (82876-62829-2; 2005).

Example 10. Gravel B: Kirvy Brown, ‘Lord Do It’ (Tax. 1, 3, 6).

Example 11. Gravel C: Fred Hammond, ‘God is a Good God’ (Tax. 1, 3) (01241-43197-9; 2003).

Example 12. Gravel D: Fred Hammond, ‘God is a Good God’ (Tax. 1, 3, 15).

Within this same example, we can also observe the use of the ‘grunt’, which occurs after the lines ‘let me see you clap your hands’ in bars two and four, underscoring the fundamental rhythmic pulse. The use of the ‘grunt’ dates back several decades, and is in evidence in two early field recordings of ‘Jumpin’ Judy' from the 1930s (Afro-American Spirituals, Work Song, and Ballads). In the liner notes, Shirley writes; ‘The rhythmic grunts on this record indicate the work blows of the pick or axe’. The Arkansas version illustrates a constant drum-like pulse underlying the work song, whilst the Mississippi version of the same tune includes a wider-spaced, more punctuating percussive ‘grunt’ to which Shirley refers. In its gospel context, the grunt occurs less frequently and is usually a loud, short expulsion of air on a non-specified pitch which punctuates sentences and phrases, underlining the pulse or beat within the phrase (Example 12, bars two and four). Dorothy Love Coates uses a simple and softly uttered grunt in the song ‘Trouble’ that finishes the opening phrase ‘Oh Lord you know I'm in trouble’ (Example 13) and also at the end of the first line of the second verse ‘I get so tired of being persecuted Lord’ (Example 14).

Example 13. Grunt A: Dorothy Love Coates, ‘Trouble’ (Tax. 1, 2, 5) (LC 5762; 1993).

Example 14. Grunt B: Dorothy Love Coates, ‘Trouble’ (Tax. 2, 5, 8).

Finally, Kirk Franklin also employs this technique in the introduction to ‘Jesus is The Reason’ (Example 15), placing the grunt on a strong offbeat, emphasising the skip-shuffle feel of this contemporary hip-hop inspired gospel song.

Example 15. Grunt B: Kirk Franklin, ‘Jesus is The Reason’ (Tax. 2, 27).

Screams and shouts

The ‘scream’ in gospel is an expression of exuberant joy, passion, emphatic acclamation or declaration. Clarence Fountain demonstrates a simple scream in his solo with the Five Blind Boys of Alabama in their 1966/1967 recording, ‘Something's Got a Hold of Me’ (Example 16). Fountain also employs more intense and elongated screams in songs like ‘When I Come to the End of My Journey’, whilst James Cleveland's scream at the conclusion of ‘Peace Be Still’ (Example 17) is aggressive, emphatic and surprising. Cleveland's scream provides a great contrast to the two moans that precede it, drawing a marked reaction from the audience/congregation as a result. Finally, illustrating the connectedness of these various techniques, Kirk Franklin combines a scream with two grunts, a glide/high-who and a shout (bar 7, ‘Gotchu gotcha gotcha) in the introduction to his 1996 recording ‘It's Rainin’’ (Example 18).

Example 16. Scream A: Clarence Fountain, ‘Something's Got a Hold of Me’ (Tax. 2, 6, 10, 11) (SCD-88030-2; 1996).

Example 17. Scream B: James Cleveland, ‘Peace Be Still’ (Tax. 6, 10) (SCD 7059 DIDX 26982; 1980).

Example 18. Scream C: Kirk Franklin, ‘It's Rainin’’ (Tax. 1, 6, 11, 23) (INTD-90093; 1997).

Whilst the terms scream and shout are to some degree interchangeable, the shout can be more directive (in this instance, setting up the first entry to the choir), and often suggests the need for agreement or some other response, such as is illustrated by Clarence Fountain, whose pleading adoration of ‘the Saviour’ in ‘When I Come to the End of My Journey’ becomes a more increasingly intense shout with each repetition of the phrase, before the emotionalism becomes so overpowering that the shout evolves into a scream that in turn becomes a moan (Example 19).

Example 19. Shout: Clarence Fountain, ‘When I Come to the End of My Journey’ (Tax. 2, 3, 6, 14, 16, 17, 20, 22, 23) (SCD-88030-2; 1996).

Song-speech and vibrato

Song-speech is similar to operatic recitative where the gospel singer delivers a lyric that is either half sung/half spoken or vacillates between a melodic and a spoken phrase. Clara Hudman-Gholston (The Georgia Peach) provides an early example of this technique in ‘Jesus Knows how Much we Can Bear’ where she preserves a sense of pulse, melodic shape and dialectic emphasis in the phrasing which distinguishes it from pure prose or speech alone (Example 20). Hudman-Gholston raises the pitch and intensity of the word ‘asked’ in line 1, draws out the word ‘confide’ in line 3 and also adds emphasis to the word ‘rules’ in line 5, in a manner that reflects elements of African American dialectic practice of this period, seamlessly moving back into melody in line 7.

Example 20. Song-speech A: The Georgia Peach, ‘Jesus Knows how Much we Can Bear’.

James Moore moves from a form of ‘address’ into song-speech in ‘Let us Go Back to Church’, providing an excellent illustration of the contrast between speech and song speech in a contemporary context (Example 21). Moore moves predominantly between the two semi-fixed pitches of Eb and Ab as he delivers lines two through four allowing the higher Ab to act as an emphasis or stress point, giving the extemporised text a melodic shape and a distinct pulse that works within but is not bound to the existing time-feel as played by the rhythm section (Example 22). Moore is then able to create additional emphases on key words like ‘revived’ and ‘at all times’ (Example 23) in line five by using gravel and dynamic shifts that bring Moore's interpretation of the text – a paraphrased version of Psalms 34 and 122 – to the fore. Later in the text, Moore clips the word ‘continually’, and emphasises the next phrase ‘be in my mouth’ by elongating the notes and adding new notes to the melody, aligning himself to the character of David in the text, and recontextualising this ancient scripture into contemporary gospel practice. Song-speech in particular allows the gospel singer to become gospel preacher, blurring the distinction between the two.

Example 21. Song-speech B: James Moore, ‘Let us Go Back to Church’.

Example 22. Song-speech C: James Moore, ‘Let us Go Back to Church’ (Tax. 2, 3, 17) (MCCD 093; 1992).

Example 23. Song-speech D: James Moore, ‘Let us Go Back to Church’ (Tax. 1, 3, 16).

Timbre and register shifts

Boyer (Reference Boyer2000) makes several key observations about the timbral quality of the early African American gospel voice; ‘Singers made no pretence [sic] of placing the voice “in the head”, as was the practice of European singing masters, but chose the voice of those “crying in the wilderness”’(p. 11). He describes the voice of gospel singer Arizona Draines as ‘tense’ and ‘almost shrill’; Mamie Forehand as ‘low’ and ‘lazy’; Washington Phillip and Joe Taggart as ‘dirty’; and Willie Johnson as ‘hoarse’ and ‘strained’. Boyer provides us with an insight into the breadth of tonal variation both from singer to singer and within a single performance by one singer and, just as significantly, the community's acceptance of this.

Of additional interest in this field is the manner in which many gospel singers make little or no attempt to achieve a consistency of tone across their vocal range, choosing to use the naturally occurring tones of the various vocal registers in the head and chest voices. Extremes of range, the use of falsettos and the ‘break’ in the voice that can occur between registers – referred to as a ‘cry’ – are also used by the gospel singer to produce an ever-wider palette of tone colour to add to the power of the emotional delivery of their performance. Marion Williams demonstrates many of these techniques in her recording ‘There's a Man’. The opening line, ‘There's a man’, demonstrates the nasal quality of her voice, particularly over the sustained notes on ‘man’, which contrasts markedly with the round, warm tone she achieves in the lower register on the second syllable of the word ‘a-round’. Williams also re-emphasises the second vowel sound by taking a breath in the middle of the second vowel (‘ou’) and re-sounding it, but with a consonant ‘h’ at the beginning of the vowel (Example 24). The timbre shift across these measures is dramatic and creates a complex tonal shift that is subjugated to the expressive. At the conclusion of the phrase, Williams employs an elongated moan and high sustained note or ‘wail’, supported by a fast gospel vibrato, before descending with a melismatic run that develops into a moan and a short vocal register break or ‘cry’ (Example 24) that returns to an elongated moan to conclude. The contrast in timbre is marked, particularly where the gravel tone at the beginning of Example 25 develops into the falsetto-like tone of the sustained Eb, and the register shift or ‘cry’ in bar two, also on Eb. Not only does Williams not try to disguise the break in register and tone, she emphasises it and uses the ‘cry’ to create an intensely rich and powerful emotional expression.

Example 24. Timbre/register shift A: Marion Williams, ‘There's a Man’ (Tax. 16).

Example 25. Timbre/register shift B: Marion Williams, ‘There's a Man’ (Tax. 1, 2, 7, 9, 18, 20).

Pitch

Slides, glides, wails and the hi-who

In the literature, the terms ‘glide’, ‘slide’ and to a lesser degree ‘wail’ are used interchangeably and most often without precise definition. For the purposes of clarity, a slide here will be defined as a glissando-like movement either immediately approaching or leaving a note or other vocal tone. Cissy Houston provides some excellent examples of this in her recording ‘Stop’, firstly approaching the word ‘there’ with a short slide from immediately underneath the destination note, F4 (Example 26). Example 2 employs a more conventional notation, whereas Example 1 employs the notation that the author has assigned for this technique so as to establish the new ‘symbol’ as an analytical device, differentiating it from the historical performance practice associated with the conventional glissando. Following this example, Houston again uses a slide (Example 27), in this case to emphasise a pinnacle point in the phrase – ‘Stop, look and listen’. To further illustrate, the Georgia State Mass Gospel Choir also employ a major, whole-choir slide in their recording ‘Joy’, sliding from a C7 chord to a first inversion Bb chord (Example 28).

Example 26. Slide A: Cissy Houston, ‘Stop’ (Tax. 10) (51416-1312-2; 1997).

Example 27. Slide B: Cissy Houston, ‘Stop’ (Tax. 10).

Example 28. Slide C: Georgia State Mass Choir, ‘Joy’ (Tax. 10) (SCD 7129 DIX 70627; 2002).

The glide is not unlike the slide, but occurs between more than two pitches over the length of the phrase. Aretha Franklin sings a simple glide across the word holy in her recording of ‘Wholy Holy’, gliding from a Bb, up to a D natural and back though a C to the starting tone, Bb (see Example 29). As part of the glide, the initial Bb in bar 1 is barely sounded, is pitched sharper than the written note indicates, and is difficult to meaningfully notate with traditional rhythmic values. Therefore, Example 30 employs the now established notation for an upward and downward slide, with a duration bracket above to indicate the length and pitch direction of the glide.

Example 29. Glide A: (1) Aretha Franklin, ‘Wholy Holy’

Example 30. Glide B: (2) Aretha Franklin, ‘Wholy Holy’ (Tax. 12).

Finally, Mahalia Jackson employs this technique in ‘Hands of God’ (Example 31) in a manner that could be considered typical for this technique, coming in the final measures and at the moment of greatest intensity (the pinnacle point of the song), and continues to both slide and glide to the conclusion of the song.

Example 31. Glide B: Mahalia Jackson, ‘Hands of God’ (Tax. 12).

The gospel ‘wail’, often preceded by a slide or glide, is a relatively high pitched, sustained tone or series of sustained tones that the gospel singer places above an existing arrangement or song that may or may not contain a specific lyric content which is often also sung with a degree of gravel tone. The wail functions in a similar fashion to a moan, but is generally more positive in effect, as Sam Cooke gently demonstrates in ‘I'm Gonna Build on That Shore’. He employs the same technique in a more aggressive and passionate manner in ‘Until Jesus Calls me Home’, where he uses single words from the lyric line and added interjections such as ‘well I'm gonna sing’ and ‘yeah about Jesus’ for his short but impassioned wails.

Alex Bradford uses an ‘oh’ sound for his gravel-inflected wail in ‘If You See My Saviour’ in which he also uses cry in between the first and second tones (Example 32). The wail is seen in its most dramatic form in Lanelle Collins' solo at the conclusion of ‘Work that Thang Out’ where, following a longer passage of wail-like phrases (‘He's able’, ‘He'll work it out’, ‘He'll fix it’), she concludes with an elongated wail over the expression ‘o yeah’, adding an emphatic agreement to the sentiments outlined in the preceding lines (Example 33).

Example 32. Wail A: Alex Bradford, ‘If You See My Saviour’ (Tax. 1, 7, 10).

Example 33. Wail B: Lanelle Collins. ‘Work that Thang Out’ (Tax. 1, 2, 3, 10, 11) (51416-5240-2; 1996).

The ‘high-who’ is a device that Boyer (Reference Boyer2000) describes as deriving from the manner in which Marion Williams would sing a high note using an ‘oo’ sound, preceding it with a ‘wh’ consonant for added percussive effect (p. 107). This technique becomes standard practice in gospel, and typically the high-who is placed at the end of one chorus leading into another. Williams uses this technique at the conclusion of ‘Nobody Knows, Nobody Cares’, linking two chorus together with an increasing gravel tone, two breaks (cries) and the high-who (Example 34).

Example 34. High-who: Marion Williams, ‘Nobody Knows, Nobody Cares’ (Tax. 1, 2, 3, 7, 14) (LC 5762; 1993).

Blues inflection

Gospel singers will often superimpose a ‘blues inflection’ or minor pentatonic improvised embellishment on a gospel melody that is of a predominantly major tonality, resulting in a marked shift in both sound, intent and affect that recalls the ‘down home’ sound of the blues. Mahalia Jackson uses this technique in ‘The Upper Room’, where the blues inflection is particularly obvious towards the end of this recording. The music momentarily calms with the lead bass taking over the melody, and Jackson outlining the major tonality (G major to D7 chord) with a repetitive, backing vocal-style rhythmic phrase ‘in the upper room, in the upper room’ (Example 35). Jackson then increases the dynamic level and intensity of her vocal line, employing a series of blues inflections in her improvised embellishments on the original melody (Example 36).

Example 35. Blues inflection A: Mahalia Jackson, ‘The Upper Room’ (R2CD-40-39/1; 2001)

Example 36. Blues inflection B: Mahalia Jackson, ‘The Upper Room’ (Tax. 14).

The subtlety of this technique is illustrated by Marion Williams in ‘Shall These Cheeks go Dry’. Williams' opening phrase hints at an F major pentatonic scale (F4 drops to D4, the major 6th), which she then contrasts with the use of a blues inflection (F4 to Ab4, with the Ab sounding slightly lower than the specified pitch, as indicated by the gospel nomenclature), followed by downward slide, that immediately changes the impact and resonance of the song (Example 37).

Example 37. Blues inflection C: Marion Williams, ‘Shall These Cheeks go Dry’ (Tax. 10, 11, 14) (LC 5762; 1993).

Finally, the soloist on James Cleveland's ‘Just a Sinner’ has based the majority of her improvised embellishments on the major and major pentatonic scales. With both ‘G’ scale tones in bar two sounding as ‘blue-notes’ – pushed flatter than written pitch, but not flat enough to warrant being notated as Gb – the blues inflection she uses towards the end of the excerpt stands out for the subtle change it brings about in melodic and emotional direction (Example 38).

Example 38. Blues inflection D: James Cleveland, ‘Just a Sinner’ (COL 6102; 1998).

Passing tones, bends, neighbour tones and the gospel gruppetto

Boyer was the first to describe and notate the fundamental melodic ornaments expected to be executable by the majority of gospel singers (Boyer Reference Boyer1979, pp. 24–7).

(1) Ascending and descending passing tones

(2) Upper and lower neighbour tones

(3) Bends

(4) Gospel gruppetto

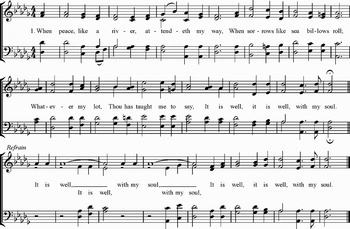

Boyer originally analysed a ‘gospelised’ version of the traditional Joseph M. Scriven and Charles C. Converse hymn ‘What a Friend We Have in Jesus’ to describe and notate these ornaments, and here Boyer's analytical framework has been applied to another frequently ‘gospelised’ traditional hymn, ‘It is Well’ by Horatio Spafford and Philip Bliss (Example 39). Dello Thedford and the author arranged this hymn for a contemporary male vocal quartet in 1996, and although the notation is rhythmically closer to the intended performance style (Example 40), particularly with the use of the compound metre, there remains a significant and audible difference between the arrangement as it is notated and as gospel singers perform it, especially with respect to the melody. The following ‘gospelised’ rendering of the melody (Example 41) is taken from the melody in the first tenor part and further illustrates the fundamental melodic devices that Boyer has previously described.

(1) Ascending and descending passing tones. Passing tones join two notes of the original melody that sit a third apart. Letter (a) in bar 2 highlights the descending, whilst letter (b) in bar 3 highlights the ascending passing tone.

(2) Upper and lower neighbour tones. The vocal agility of the gospel singer is in part demonstrated in their ability to ‘execute an ornamentation in a short rhythmic space’ (Boyer Reference Boyer1979) for which the use of upper and lower neighbour can be used. The upper neighbour is indicated in bar 5 at letter (d), with the lower neighbour in bar 6 at letter (e).

(3) Bends. Boyer states that the upper and lower bend are equally common and occur where the singer ‘plays’ the last note of a phrase or line, meaning that they begin the note on pitch and then bend the note upwards or downwards by varying intervals, highlighted here in bar 7 at (f) – a downward bend of a fourth – and in bar 9 at (g) – an upward bend of a second.

(4) Gospel gruppetto. The gospel gruppetto, also referred to as a ‘melisma’ or traditionally as ‘worrying the line’, is described by Henderson as ‘… the folk expression for the device of altering the pitch of a note in a given passage or for other kinds of ornamentation often associated with the melismatic singing in the Black tradition’ (Henderson Reference Henderson1973, p. 41). Boyer originally used the term ‘gruppetto’ for this technique, describing it as the execution of ‘… several tones in rapid succession, either in conjunct (stepwise) or disjunct (separated) motion, either ascending or descending, or in an ascent-descent combination’ (Boyer Reference Boyer2000, p. 25). However, the use of the term ‘gruppetto’ in this context is misleading in that it has been in common usage in the Western European classical tradition since the sixteenth century and therefore the author has consequently applied the term ‘gospel gruppetto’ to clearly differentiate these two terms.

Example 39. ‘It is Well’, H. Spafford and P. Bliss (Tax. 14).

Example 40.

‘It is Well’, arrangement by D. Thedford and A. Legg.

Example 41. ‘It is Well’, gospelised melodic line.

The gospel gruppetto occurs over a number of successive tones, usually more than three, and can be placed over single harmonic centre or chord, or lead from one chord to another, often employing predictive elements of the new chord within the melodic structure of the gruppetto. A disjunct gospel grupetto that re-sounds the existing harmony is marked here in bar 5 at letter (c), with a conjunct gospel grupetto that moves from a Bmaj9 chord to an E9 chord marked in bar 10 at letter (h). Table 2 lists some useful additional examples of these gospel vocal ornaments, and which are annotated in Example 42.

Example 42. Additional vocal ornaments, notated examples.

Table 2. Additional vocal ornaments.

Even within these three foundational gospel singing technical categories – the gospel moan, timbre and pitch – the scope for individual interpretation and manipulation of the essential musical material is particularly significant and the degree of individual interpretative flexibility and possibility that is afforded the gospel singer is substantial.

The role therefore played by the gospel singer is of particular significance within African American gospel music. In performance, the gospel singer is able to manipulate timbre, pitch, rhythm and even structural elements within the music to a particularly significant degree. Each new performance is improvised or ‘instantaneously composed’, and such is the centrality of this concept within African American gospel that many individual gospel songs are often more closely identified with a particular interpretation of the song by a specific gospel singer, than they are with the compositional style and performance intentions of the original composer. Indeed, the vocal ‘re-working’ of the W.H. Brewster song, ‘God is Able’ by the Ward Singer's Clara Ward and Marion Williams so resonated with the African American community, that eventually Brewster himself agreed to change the name of his song to ‘Surely God is Able’ to better reflect Ward's new opening and ultimately defining phrase:

Surely (surely), surely (surely),

Surely (surely) surely (surely)

He's able (He's able) to carry you through

Conclusion

The influence of the African American gospel singer on the development of the African American gospel genre is in fact a defining one. From the totally improvised and highly personalised songs sung by an individual whilst under the influence or ‘possession’ of the Holy Ghost (as witnessed during the Azusa St. revival meetings in the early 1900s), to the vocal style of the Reverend W.M. Nix which so profoundly influenced Thomas Dorsey during the 1921 National Baptist Convention; from Mahalia Jackson's remarkable vocal agility, unique vocal delivery and ability to find a resonance for gospel outside of African American religious culture, to Aretha Franklin's highly emotional, impassioned and uninhibited gospel vocal style that in turn helped define African American popular music, especially during the 1960s; the performance practices of the gospel singer are central to the shaping of African American gospel music, and to its broader impact on Western popular music and world culture in general.

The taxonomy of musical gesture for African American gospel music introduced in this article was originally developed as a means by which the author could record, recall and communicate the essential elements of this vast and complex performance style into an Australian musical context, where the contextual touchstones of gospel music were not present to any significant degree. The authors' taxonomy, in part presented in this article, now provides a more universal frame of reference for the definition of essential terminologies and performance practices inherent within African American gospel music.

It should be noted that the author is not suggesting that the taxonomy be used in the creation of a music score that could be ‘read’ in a conventional sense within a performance context. The great depth of subtlety and complexity of nuance and gesture that the taxonomy attempts to capture often makes the annotated score understandably complex and therefore difficult to read in ‘real time’. The significance of the taxonomy, and the research and analysis which underpins it, lies in the provision of definitions and descriptions of musical techniques that are deeply embedded within the African American gospel tradition, and which are not always clearly understood outside of this performance culture. The taxonomy therefore also provides the conductor/director, researcher and performer with a defining, instructive and very usable reference tool which graphically represents, cross-references and codifies the essential gospel singing techniques that have influenced and shaped the development of African American gospel music.

Taxonomy

Gospel nomenclature