I am the Entertainer, I come to do my show.

Heard my latest record spin on the radio?

Aw, it took me years to write it; they were the best years of my life!

It was a beautiful song but it ran too long;

If you're gonna have a hit, you gotta make it fit,

So they cut it down to 3:05.

Thus proclaims the fifth stanza of Billy Joel's ‘The Entertainer’, a song from his second Columbia album, Streetlife Serenade (1974). Verse by verse, the song presents a litany of the commercial pressures faced by an artist struggling to make his mark in the record industry, as his work is commodified and otherwise compromised. ‘The Entertainer’ was a first-person follow-up to the ostensibly autobiographical ‘Piano Man’, the title track of his previous album that had enjoyed US national airplay. Therefore, Columbia hoped to use this new tune in the promotion of Streetlife, and released ‘The Entertainer’ as a single for the widest possible exposure and to build upon the narrative of Joel's self-portrayal. There was one problem: its third stanza included the rock star's boasts, ‘I played all kinds of palaces, I laid all kinds of girls’, not appropriate for airplay in the necessary markets. So, as if in fulfilment of the composition's prophecy, the offending verse was removed, thereby abridging the recording's duration from its album length of 3′39ʺ to … if you followed the lyrics above, you may not believe it: for the single, they cut it down to 3′05ʺ (see timings as indicated on the record labels shown in Figure 1).Footnote 1

Figure 1. Selected vinyl pressings of ‘The Entertainer’. (a) LP label; (b) Mono promo; (c) Stereo stock copy. The matrix number for stereo single pressings is ZSS 159589; the mono mix appeared only on the promo (thus the ‘P’ in the matrix prefix).

Many pop-rock recordings have had similar fates, if never so ironically, for many reasons. Others have enjoyed the benefits that come with alternative mixes, whether produced concurrently for different markets, or as the result of the revisitation of a classic track decades after its initial appearance. Both competing interests and reflective insights are at work in the sometimes-friendly, sometimes-forced collaborations among composing and performing artists, record producers, artists, company management and radio programmers that may bring a pop recording from the recording studio to the marketplace in numerous simultaneous versions.

This article will review alternate mixes and edited versions produced for various purposes over the past half century for stock singles, promotional singles, albums and reissues. These all evidence a negotiated form of intertextuality of uniquely central importance to the record industry, a form that has not previously been systematically reported upon by music scholars, while they also support a more informed perspective on the questions of ‘definitive versions’ and ‘authoritative text’ that have interested researchers of popular music over recent decades. Intertextuality as a scholarly endeavour is ‘Julia Kristeva's attempt to combine Sausseurean and Bakhtinian theories of language and literature[, which] produced the first articulation of intertextual theory, in the late 1960s’ (Allen Reference Allen2000, p. 3). For Kristeva and her followers, every text is a largely unintended composite of references to prior discourses. Whereas the types of intertextuality to be explored in this essay involve forms of authorial intention not presupposed in the classic sense of intertextual relations, my dependence upon this body of work is supported by – and to a degree suggested by – an interesting and highly relevant essay by Serge Lacasse.Footnote 2

Whereas references will be made to the entire history of rock, most examples in this examination will be taken from vinyl sources. In an age of viral music-making by which a recording artist can have any number of unknown freelance mash-up collaborators (often by design), at a time when a consumer's search for a simple song download results in point-of-sale offers of numerous quasi-documented and undifferentiated versions of a targeted recording (easily resulting in the inadvertent purchase of an unintended item), and with opportunities growing as unauthorised releases are available to scholars as never before, it is a propitious time to review the practices of past decades (generally, but not exclusively, those given to vinyl pressings) to see how we arrived at this point. This article takes steps towards such a review.

The creation of different mixes or edits of a recording for simultaneous exposure in different markets, exemplified by ‘The Entertainer’, is but one type of a condition that might be called intratextuality, whereby a network of differing sonic products is traceable to a single source recording. Table 1 outlines the 10 major types of intratextuality that can lead to this condition; the Joel track falls under Type 5 which, along with Type 4, forms the basis of the present article. To contextualise these intratextual techniques, one might consider them alongside broader forms of pop-music intertextuality. These latter would include very closely related types such as complete remakes required by lost master tapes or various contractual issues (as with Little Richard's Vee Jay remakes of Specialty originals), hits remade after an artist joins a new band (The Great Society's ‘White Rabbit’ redone by Jefferson Airplane), live-vs.-concert and acoustic-vs.-electric versions of performances (Bruce Springsteen's ‘Tenth Avenue Freeze-Out’ and Bob Dylan's ‘George Jackson’, respectively), songs enjoying completely new conceptions years after their initial reception (Ani DeFranco's Canon), medleys (Spyder Turner's ‘Stand By Me’), and overdubs added to tracks originally created by deceased ‘ghost’ superstars (Natalie Cole's overdubs onto Nat King Cole's ‘Unforgettable’). Also related are more distantly derivative categories such as radical recompositions under new titles, cover versions, musical quotations and plagiarism, stylistic borrowing and (attributed or suspected) model composition, sampling from one recording into another, and homage forms such as the break-in, parody, follow-up, sequel and answer songs.Footnote 3 (Of course, more ephemeral forms of multi-song reference exist, as in a listener's linking one song with another that had once appeared adjacent to it in an obsolete album sequence, or in that listener's holding even more personal associations extrinsic to others' experiences.)

Table 1. Ten types of intratextuality in recorded popular music, classified as to original sources and the alterations they undergo.

Type 4. Differing mixes of the same edit

Stock, promo, rush, reissue and 12ʺ pressings

Before continuing with particulars about the simultaneous appearances of varied mixes, I should define each of the different sorts of single 45-rpm pressings on which they would appear. ‘Stock’ singles are those copies manufactured for both jukebox play and home consumption. They are warehoused and retailed, either through mass shipments to dedicated record stores, or distributed by rack-jobbers to general outlets such as department stores.Footnote 4 In some cases, stock copies would be rush-released with a provisional label (see an example in Figure 2), but not to my knowledge carrying any recording other than the one on the eventual hitbound pressing. The label and dead wax would often carry the matrix number, which identified the master take documented as such on the studio log and tape box and given to the lathe operator so the proper recording would be mass-produced.Footnote 5

Figure 2. Vinyl single releases of ‘Dark Horse’. (a) Rush copy; (b) Stock copy. (The photo of the stock copy, printed in very light blue, has been enhanced for both contrast and brightness.)

Sometimes the stock single would be distributed to radio station programme directors for airplay but, more often, broadcasters would be given specially marked promotional discs, known as promos, demos (‘demonstration’ discs) or DJ copies. Promos are sometimes referred to as ‘white label’ copies, misleading in that their labels were only sometimes white, and leading also to confusion with the plain appearance of many rush copies. Some variation of ‘not for sale’ would be printed or stamped on these DJ copies to make it clear that no gifts of value were exchanged for programming promises. This was a response to the late-1950s ‘payola’ scandal in which certain US record companies were found to have made undisclosed payments to radio programme directors and on-air personalities for plugging their product. These promotional discs frequently contained mixes and edits varying significantly from those on stock releases which would often, in turn, differ from album mixes of the same recording. One major reason for the difference was the fact that singles almost always contained mono mixes as against the stereo mixes heard on most LPs, until early 1968 when the Rascals' ‘A Beautiful Morning’ and the Doors' ‘Hello, I Love You’ blazed the trail of stereo 45s. (AM radio, the primary outlet for top-40 promotion, could only broadcast monophonically.) At times, stereo and mono mixes would differ only in terms of relatively minor qualities such as compression and balance, whereas in other cases the mix would be substantially different. Also of interest to collectors and researchers is the fact that poor-selling singles are sometimes very hard to find in their stock format, even though DJ copies (normally with far fewer copies having been pressed) are not always hard to come by. This is the situation with such recordings as the Paul Winter Consort's ‘Icarus’, an instrumental number played unannounced by many radio stations as a bumper between programme segments, but a record that failed to break Billboard's weekly ‘Hot 100’ chart (see Figure 3). Another such instance is Ringo Starr's ‘Drowning in the Sea of Love’, a non-hit released by Atlantic in 1978. In this case, the company tried valiantly to promote the record so DJ copies are fairly abundant, but consumers were uninterested so the few stock copies that made it to the marketplace were returned and melted down, thereby becoming one of the scarcest pieces of Beatle vinyl offered for general release. Similarly, one can find DJ copies of the Mothers of Invention's 1966 single ‘Who Are the Brain Police’ for a price, but the stock copy eludes even the most persistent collector. Usually, DJ discs would pair the same A- and B-sides as on the stock copies (occasionally allowing the radio industry to overturn a record company's decision as to which side would be intended for broadcast, as was done with Steam's inadvertent 1969 hit, ‘Na Na Hey Hey Kiss Him Goodbye’) but, as the same hits came to be played on both AM and FM stations by the late 1960s, promo discs would tend to pair mono and stereo mixes, or short and long versions of the same song.

Figure 3. Demo disc of ‘Icarus’.

Aside from stock, rush and DJ copies, one must also be aware of the reissue format. Once a hit dropped off the charts, it would become a candidate for re-release, often in a back-to-back-hit arrangement that would pair two reissues (almost always by the same artist) for the price of one. These reissues were usually re-pressings of the hit single mixes, but alternatively they could establish the album version as the subsequently uniformly marketed mix. Once a hit faded into memory, the dedicated promotional mix was almost never heard again. Oldies were also heavily sold through the 1970s as stock cutouts, signified by 0.4-cm diameter holes drilled through the label identifying those discs as ones marked down as bargains and non-returnable to the manufacturer. It might also be mentioned here that masters would be owned by the original record company until sold, but that these recordings would often be leased by indies and majors alike to outside parties, an arrangement particularly prevalent with the scaling back of vinyl pressing in the 1990s. Third-party reissues would usually be based on hit single masters until late into the 1980s, when mono recordings all but disappeared from even the 7ʺ format (except in cases where the mono master was the only one available). In at least one case, a new edit was created for a reissue: the Doors' ‘Light My Fire’ (1967) was a huge hit on both FM and AM radio, the AM outlets playing the mono version (2:52) that eliminated the organ and guitar solos heard on the FM-broadcast album (6:50). When the track was reissued as an ‘oldies’ single in Elektra's ‘Spun Gold’ series in 1971, two new stereo edits (one at 3:02 for the American reissue, the other at 3:04 for Canadian release) were pressed into service, both deleting most of the solo break and thus simulating a stereo version of the original hit. Additionally, largely with the emergence of disco, the mid-1970s brought the arrival of the 12ʺ single, which would allow for extended mixes and even multiple versions on the same disc.

Mono-vs.-stereo mixes

Sometimes a single's mono mix would be balanced differently from the stereo album. In the Moody Blues' ‘Another Morning’ (the 1968 B-side of ‘Tuesday Afternoon’), for instance, the lead vocal is much louder in relation to the band for the 45 than it is for the LP. As a similarly minor adjustment, promotional records would tend to feature mixes whose dynamic range was highly compressed and whose signal was boosted in midrange frequencies for more satisfactory AM broadcast, particularly in consideration of low-quality reproduction and listening environments such as found with hand-held and car radios. For this reason, the promo mix of Simon and Garfunkel's ‘Mrs. Robinson’ (1968) has a louder and punchier bass drum than is heard in the stereo album mix, and the single pressing of Led Zeppelin's ‘Immigrant Song’ (1970) is far more compressed and fills a narrower EQ band than the version heard on the full-range album.

Somewhat more interesting are differences that distinguish mono from stereo mixes of the same edit. Some producers, notably Phil Spector and Brian Wilson, preferred a monophonic product because they could exercise no control over the balance of two stereo channels when reproduced from disc. In addition, portions of a stereo program can be altered, sometimes to catastrophic effect, when a centered image is partly or fully cancelled due to waveform phasing that results particularly in large spaces when a listener is much closer to one loudspeaker than to the other. But stereo did not become an industry standard until the late 1960s; George Martin often said that the Beatles would not even be present for stereo mixing sessions through most of their career. The group's first album, Please Please Me, was recorded live on two tracks in order to enable balancing of vocals against most of the instruments for the mono release, resulting in an unsatisfying ‘stereo mix’ for a limited pressing that totally separated the two working tracks. The 1987 CD releases of Help! and Rubber Soul were given new digital mixes to replace sub-standard stereo mixes originally done in 1965. When their recordings were first prepared for American release, not only were Beatle albums compiled with different songs from those found on their UK counterparts, and not only were they given a great deal of added reverb (so as to satisfy a different taste from that characteristic of British listeners), but Dave Dexter, EMI's Hollywood producer, created ‘duophonic’ stereo mixes by artificially separating new channels from monophonic sources by frequency band, making for a high channel and a low channel. This abysmal presentation was characteristic of most of the Beatles' early ‘stereo’ albums on Capitol (see Spizer Reference Spizer2000, 245–54).

Aside from earlier effects such as motorcycles crossing the soundstage, stereo experimentation began in 1966 with Tom Dowd's work for Atlantic with the Young Rascals, notably in the ‘One! Two! Three!’ count-in to ‘Good Lovin'’, which criss-crossed the two-channel divide in rapid fire motion.Footnote 6 This sort of stereo effect emerged just in time to encourage all sorts of trippy psychedelic effects (including phasing, Leslie speakers, exotic filtering and tremolo) for headphone-inspiring artists such as Jimi Hendrix, the Moody Blues and Led Zeppelin. Panning quickly became a hallmark of drum-set mixing; by 1969 (see the Beatles' ‘The End’ and Blood, Sweat & Tears' ‘And When I Die’), multiple microphones were required to best capture a drummer's work, and the resulting individual sonorities would be bussedFootnote 7 to different placements in the stereo image. This approach to drums became an industry standard, so that even tracks like Boney M's ‘Ma Baker’ (1977) feature highly panned drums on the ‘Remix I’ CD but not at all on the original stereo 45.

Digital remixes of older product often feature newly panned elements. This takes advantage of the fact that automated mixing need not be done in real time; all elements of the mix can be programmed in any order following lots of experimentation, whereas the final mix made in analogue mastering would have to be performed live, all hands working the pots, faders and switches as the tape spooled by – often requiring many rehearsal takes to get a complex mix just right. Digital remastering thus features far more varied approaches to the stereo image than did earlier mixes, whether the programme is as conservative as the Carpenters' ‘We've Only Just Begun’ (1970; note the newly sparkling high-register piano work, the louder bass, the gradual fading-down of the piano, and the altered clarinet and piano staging in the 1991 revision) or as radical as Megadeth's ‘Remixed and Remastered’ series (2002+, with wonderful critical notes by Dave Mustaine). All-new transparency is bestowed on old recordings by 5.1 surround sound, as with the 1999 Yellow Submarine Songtrack mixes made for a wide array of Beatle songs.

Muting and other remixing effects

Of still potentially greater interest are variants in muting. In the final composition of a 4-, 8- or 16-track working tape that may have been built up with layer upon layer of overdubs by any number of performers, many components may be captured here and there that are later chosen for exclusion from released mixes. This is not done by erasing the passages in the working tape, but by preventing their transfer to the final mix by zeroing the fader for that given track at the desired moment during the reduction of the working tape to the one- or two-channel master. It is this process that allows two different guitar solos in the two different stereo mixes of the Beatles' ‘Let It Be’: one for the 45 (currently part of Past Masters) and the other for the album (Let It Be). The 8-track working tape of ‘Let It Be’ contains alternate solos from both George Harrison (coloured by his Leslie cabinet) and John Lennon; only the former was mixed into the single, and only the latter appeared on the album.

The edited mono 45 mix (3:13) of the Grateful Dead's ‘Truckin'’ (1970) has completely different lead guitar work by Jerry Garcia from that heard in the same take's appearance (at 5:09) a year later on American Beauty; this is more likely the result of the muting of different tracks in a mix than of a later recording replacing an earlier one. In the Beatles' ‘I'm Only Sleeping’ (1966), the mono and stereo mixes feature different portions of the working tape track devoted to backwards guitar, because different passages were muted out for each mix. Also note how the mono mix of the Rolling Stones' ‘Time Is On My Side’ (1964) features a bent-string guitar intro by Brian Jones that is muted out of the stereo intro. Alternative guitar solos can be heard in Deep Purple's ‘Smoke on the Water’ (1973), as elements of the 16-track working tape are laid bare in Roger Glover's 1998 remastering of Machine Head.Footnote 8 One astounding pair of mixes is that for the Moody Blues' ‘Question’ (1970), whose single version opens with solo diminished-seventh chords on an acoustic 12-string, all obscured by Mellotron and other band parts which spell the chords differently on the album mix. Muting allows for a massive edit in the case of the 45 ‘Total Mass Retain’, the advance single (charting August 1972, with a timing of 3:16) for Yes's Close to the Edge LP (October 1972, taken from a sidelong suite at 18:50). The single mix jumps from the album's opening ‘rainforest’ effects to the line ‘I get up’ through a transitional use of the phrase ‘Seasons will pass you by’, which phrase lacks the vocals heard on the album. The album's vocal parts are muted out of the transition, allowing the single something of a fresh start.

Muting can cover a multitude of sins. The original mono mix of the Buckinghams' ‘Kind of a Drag’ (1966) was not marred by the rhythmically flabby and intonationally sharp trumpet solo that engineers neglected to mute out of the stereo mix. Early expurgated censorings would simply mute out offending words, such as the ‘Goddamn’ that does not appear in the stock single of the Grateful Dead's ‘Uncle John's Band’ (1970). Radio stations had to take it upon themselves to bleep out the hook-carrying ‘Christ!’ expletive in the Beatles' ‘The Ballad of John and Yoko’ (1969). The Steve Miller Band's ‘Jet Airliner’ (1977) was an early and quaintly mild example of a band producing tacit ‘clean’ and ‘explicit’ versions of the same take; where the album version sang of ‘funky shit goin' down in the city’, the hit single was a bit more incongruous (and laughable) in celebrating ‘funky kicks goin' down in the city’. Sometimes muting produces other sorts of minor variants, as when Janis Joplin's vocal is heard double-tracked on the 45 but sole-voiced in stereo in Big Brother and the Holding Co.'s ‘Down On Me’ (1968). Those familiar with the stereo stock-single version of the Doors' ‘Touch Me’ (1969), or its mono promo as played on the radio, were surprised to hear Ajax cleanser's advertising catchphrase ‘Stronger Than Dirt’ intoned at the end of the stereo mix for The Soft Parade, as these words had been muted from the well-known hit mixes.

In some cases, wholesale remixes produced muting variations among a host of other differences. The Grateful Dead's albums Anthem of the Sun (1968) and Aoxomoxoa (1969) were highly experimental blends of unconventional studio and live concert recordings; the simultaneous use of two full drum sets was small potatoes among the challenges faced. Only years after the records' initial release did band members and engineers have a strong sense of a desired texture, so both albums were remixed in 1971, reducing the status of the previous stereo mixes to that of archival artefacts. Nilsson's 1971 album, Aerial Pandemonium Ballet, reworked the mixes of selections from his first two albums, Pandemonium Shadow Show and Aerial Ballet. It became fashionable in the 1980s to mark singles as containing mixes not heard elsewhere; borrowing from the dance-mix tradition, mainstream artists such as Billy Joel (‘Keeping the Faith [Special Mix]’, 1985 and ‘All About Soul [Remix]’, 1993) would frequently release singles with instrumental parts not heard in the better known album versions. And later mixes could also satisfy a scholarly curiosity, as when the vocal parts of the Beach Boys' ‘Wouldn't It Be Nice’ (on a 1996 three-selection EP from Sub Pop) or the Beatles' ‘Because’ (Anthology 3, 1996) would appear without the distractions of the muted instrumental backing, a technique predictive of such future made-for-remixing a cappella productions as Jay-Z's Black Album (2003).

Type 5. Differing edits of the same recording

Whereas varying mixes of the same recording can lead to strong intratextual contrasts, greater variations are provided by differing edits, particularly those pressed on tightly constrained singles as opposed to more forgiving albums. Passages ranging in length from isolated sonorities to multiple formal sections could be excised. Many cuts were made to tame an album-length song for the radio-friendly confines of three minutes or less, or to mark improvisatory instrumental passages as extraneous; the scalpel might reduce excess effectively or inflict real damage.Footnote 9 And the need to adapt programmes to physical limitations was one that vexed early record producers, beginning with attempts to capture symphonic works on multiple sides of 78s (the binding together of multiple discs in a unified package leading to the designation ‘album’). Both of these issues – limitations of both physical and marketing formats – came together in at least one 1954 release, the Listener's Digest of condensed classical recordings in a 10-EP set which presented edited versions of Beethoven, Brahms and Tchaikovsky for the listener who did not need development sections.Footnote 10

Edits to the coda

I will classify and discuss recording edits as to what portions of a composition may be excised or altered, beginning with more ‘exterior’ passages, the coda and the intro, moving then to more essential parts of songs. Many codas involve a refrain that may be repeated nine times or more. Usually, if one mix fades earlier than the other, the shorter version belongs to the single, the longer one to the album. This is true of such songs as Bob Dylan's ‘Like a Rolling Stone’ (1965; the single is marked 6:00 but is actually about 5:55), the Association's ‘Never My Love’ (1967), the Who's ‘I Can See For Miles’ (1967) and the Small Faces' ‘Itchycoo Park’ (1967). But the Supremes' ‘You Can't Hurry Love’ (1966) and Glen Campbell's ‘Wichita Lineman’ (1968) reverse this norm, with longer single fades than heard on the albums. At least one such variation was produced many years after the fact: although the Beatles' ‘Hey Jude’ (1968) appeared at 7:11 in both original mono single and stereo album mixes, this song's mantra-like coda was shaved down by more than two minutes to fit the Beatles' biggest hit, now 5:05, onto the 1982 compilation, 20 Greatest Hits. Santana's ‘Evil Ways’ (1970) was faded out by Columbia's engineers halfway through the album's song-ending guitar solo, paring 3:17 down to the single's 2:35. Some coda cuts were made for promo versions; the Moog conclusion to Emerson, Lake & Palmer's ‘Lucky Man’ (1971) is cut completely from the DJ copy (marked ‘short version’; see Figure 4), appearing as 4:36 on the mono stock single and 3:33 on the promo. The single version of ELP's ‘Nutrocker’ (1972) could have been reduced in any number of ways from the album edit, which threads together three blues choruses, a half-minute drum solo and other repeated passages; but it is intact except for the removal of 40 seconds of crowd roaring from the end. Oddly, the single mix (3:58) of Steely Dan's ‘Rikki Don't Lose That Number’ (1974) fades the outro just a few seconds prior to the LP's cold ending (at 4:07). Was this to give the radio announcer a heads-up and the bed for a voice-over?

Figure 4. Single releases of ‘Lucky Man’. (a) Mono side of promo (white); (b) Stereo side of promo (light blue); (c) Longer stock copy (note relatively early matrix number as compared to promos).

These very commonly differing versions are produced not with hard edits (butt splices) but with differently timed manipulations of pan pots or sliding faders on the mixing board. However, some singles did require edits for different endings: the Rolling Stones' ‘Dandelion’ and the Rascals' ‘It's Wonderful’, both from 1967, are examples. ‘Dandelion’ fades out only to be followed by a brief snippet of the single's B-side, ‘We Love You’, which briefly fades in and out. When the record is flipped, the conclusion of ‘We Love You’ is answered by a fading-in and -out of a moment of ‘Dandelion’. (These mixes are both responses to the Beatles' fading out-and-in-and-out a few months earlier at the end of ‘Strawberry Fields Forever’.) The Rascals single omits a 40-second free-for-all of sound effects, party horns and kazoos preserved on the album, Once Upon a Dream.Footnote 11 Whereas Fleetwood Mac single versions of ‘Over My Head’ (1975), ‘Rhiannon (Will You Ever Win)’ (1976) and ‘Say You Love Me’ (1976) all fade more quickly than do their album mixes, that of ‘Rhiannon’ excises only the beginning of the outro, so as to preserve Stevie Nicks's vocal improv at the end. Similarly creative splicing reduces the ending of Boston's ‘Peace of Mind’ (1977), taking 4:55 down to 3:38. The single of Kansas' ‘Carry On Wayward Son’ (1976) is however hurt by the removal of the coda's guitar solo (as well as parts of the intro, the interlude between the first chorus and second verse, half of the distorted guitar/organ-solo break and half of the main riff), as the track is cut from 5:13 to 3:26. No lyrics were harmed during the making of this single.

The crossfade

More difficult for an engineer to adjust is the pair of tracks joined by an album's crossfade, when one of the pair is chosen for a single. Thus, the acoustic-guitar intro to the Beatles' ‘A Day In the Life’ was trimmed for a 1978 single release, because the recording was taken from the stereo master for Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band (on which source the song enters via crossfade from the reprise of the title track), rather than having been remixed from the 4-track working tape, which procedure was performed for the 2006 LOVE remix. Similarly, the crossfaded tracks in the Moody Blues' Days of Future Passed (1968) led to issues when ‘Nights In White Satin’, ‘Tuesday Afternoon (Forever Afternoon)’, and ‘Another Morning’ were selected as singles from the album. Each new mix abruptly avoids orchestral transitions that were mastered with crossfades for the album. ‘Tuesday’ fares particularly badly, fading out prematurely on the chorus's half cadence. Oddly, the single mix of The Who's ‘Overture to Tommy’ (1969) fades out about 10 seconds into the album's acoustic guitar preparation for ‘Captain Walker’, instead of ending cold, which could have been easily achieved by remastering from the original working tape. Yes's ‘Long Distance Runaround’ (1972) is edited for the single with a new cold ending, whereas the album, Fragile, has this song crossfade into ‘The Fish (Schindleria Praematurus)’. In each of these cases, all appearing long before the dawn of digital mixing, it was probably thought that the hard-won stereo album mix could not be satisfactorily simulated with a new attempt, so there was no desire to return to the working tapes simply to avoid crossfades that could be trimmed away, even if the single edit was left with an awkward beginning or ending.

Cuts to the intro and interior passages

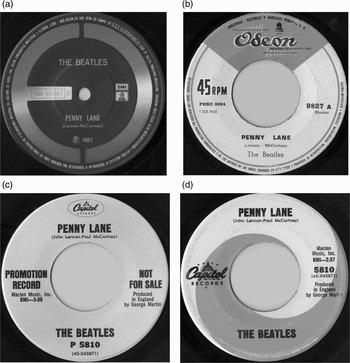

The beginning of an album's mix often had to be trimmed for the single; the opposite was much more rare. Table 2 indicates the wide variety of approaches taken in such cases. As for excisions of interior material, this could happen in the case of removals of words and phrases, or whole sections such as verses, choruses, bridges or instrumental solos, as evidenced in Billy Joel's ‘The Entertainer’. A most bizarre instance of the removal of two words exists in a 1970s Brazilian reissue of the Beatles' ‘Penny Lane’. Only this pressing excises the phrase ‘in summer’ by splicing directly from ‘four of fish and finger pies’ to ‘meanwhile back …’. Conceivably the result of a tape defect, the blip might rather have been caused by local EMI executives having gotten wind of an offending vulgarism at this point in the song, and their tape operator then mistakenly removing ‘in summer’ instead of ‘finger pies’Footnote 12 (see Figure 5). Other anomalous Beatle edits are of interest, such as ‘She's Leaving Home’ (1967). All releases of this song omit a single bar of solo cello originally performed just before each returning verse, a recurring edit revealed by the bootleg release of the recording's working tracks in Magical Mystery Year Vol. 2.Footnote 13 In ‘I'll Cry Instead’ (1964), two different mono edits (with durations of 1:43 on the American mono release of Something New and 2:04 on the British mono version of A Hard Day's Night) were released, each cobbled together from the beginnings and endings of different takes. The two versions' splices occur at different structural points in the song, the fourth verse (a repeat of the first) variously present or absent. Later examples of excised song sections include Chic's ‘Le Freak’ (1978, a 5:28 version including choruses not heard in the 3:30 edit), David Bowie's ‘China Girl’ (1983, the 5:32 album version containing a last verse/chorus combination and a second guitar solo cut from the 4:14 hit) and the Rolling Stones' ‘Saint of Me’ (1998, the 4:08 single edit bypassing a second bridge included in the 5:14 album cut as well as fading a full minute earlier). When different edits of simultaneously released versions omit one section or another, the first verse seems to be sacrosanct, later parts expendable.

Figure 5. Single releases of ‘Penny Lane’. (a) Brazilian reissue (late 1970s?); (b) Original Peruvian stock copy; (c) US promo disc (note 3:00 timing); (d) US stock copy (truncated timing reflects lack of trumpet tag).

Table 2. Various approaches taken to the trimming of a recording's introduction.

Excised instrumental passages

When different edits are marketed to different audiences, instrumental-only passages are the interior sections that drop most often by far to the cutting room floor. Perhaps out of fear of boredom, perhaps simply as a time-conscious expedient or perhaps in recognition of the fantasia quality that parenthesises the sometimes lofty achievements of an improvisatory soloist, this apparently ‘optional’ passage is frequently the major difference between commercial radio and consumer album edits. Just as some fans prefer the risky spontaneity of a live performance over the safe and clinical sheen of a studio production, fans and critics alike will typically deride the excision of any instrumental improvisation, whether exquisite or vapid, particularly because for many in the album buying market, the song itself (lyrics, verses, choruses) is often little more than a vehicle for a transfigurative solo. Table 3 lists a representative sampling of recordings in which instrumental sections may or may not appear in intratextual edits.

Table 3. A selection of recordings released in forms both with and without instrumental passages.

Recordings featuring multiple edits

A substantial proportion of records were released with versions containing or omitting combinations of the approaches discussed above. Table 4 presents a sampling of these; a few will be discussed here but others are listed without comment, leaving it to the reader to discover the nature of the edits. Note that Jimi Hendrix's name does not appear here. This is no oversight; Hendrix's singles (including ‘Purple Haze’, ‘Foxey Lady’, ‘Up From the Skies’, ‘All Along the Watchtower’, ‘Crosstown Traffic’, ‘Freedom’ and ‘Dolly Dagger’) were produced with the hit market in mind and added unchanged to albums that would also include more expansive tracks. Led Zeppelin singles (‘Living Loving Maid’, ‘Black Dog’ and ‘Rock and Roll’ among them) were also typically identical to album edits. David Bowie, on the other hand (as in ‘Young Americans’, ‘TVC-15’, ‘Let's Dance’ and ‘Modern Love’), would often appear on singles lacking multiple sections that were retained on albums.

Table 4. A selection of recordings with multiple edits.

Some of the listed edits are straightforward; that of ‘House of the Rising Sun’ cuts one verse and the beginning and ending of the organ solo (exhibiting rather poor splicing); and, as if desperate to clock in under three minutes, the organ fades out just seconds before the now more familiar cold ending on the ninth chord. ‘Just Like a Woman’ excises the verse referring to ‘her fog, her amphetamine and her pearls’, but ‘Truckin'’ keeps a verse that includes the line, ‘living on reds, vitamin C and cocaine’, cutting instead two other verses, two choruses and a bridge. In ‘White Room’, Clapton's mercuric solo is cut by a half-minute, adding insult to the loss of the third verse (‘At the party …’), the following chorus (‘I'll sleep in this place …’) and the ensuing 5/4 tattoo of violas, guitars and timpani.Footnote 14 In ‘You Can't Always Get What You Want’, the single omits the opening boys' choir among other sections. Jim Gordon's name as co-songwriter is retained on the original ‘Layla’ single, even though his contribution, the instrumental coda, does not appear on that disc; it was reinstated for the 1972 single re-release. It's interesting that the 1971 single, featuring only Clapton's portion of the composition, stalled at #51 on the Billboard charts, whereas the full, epiphanal Clapton–Gordon edit rose to #10 14 months later. Dramatic vignettes based on wrongful street arrests are cut from both ‘Living for the City’ and ‘The Message’, lending these singles the quality of pale reminiscences of the significant corresponding album versions.

More problematic are records that feature structural recompositions of long suite-like songs. On Days of Future Passed, ‘Tuesday Afternoon’ is essentially two songs (the second of which might be called ‘Evening Time to Get Away’) bridged by an orchestral transition. The single fades out before the first section is completed. The single edit of ‘Make Me Smile’ bypasses five of the album's seven continuous suite parts, one of which, ‘Colour My World’, is extracted for the hit's B-side. ‘See Me Feel Me’ (a song title given on the 45 but not on the Tommy LP or CD) is further described on the 7ʺ label thus: ‘Excerpt from the TOMMY Finale We're Not Gonna Take It’. The single skips all of the ‘Welcome to the Camp’ and ‘Hey you gettin' drunk’ verses, the following chorus, the ‘Now you can't hear me’ verse and another chorus, completely transforming the finale's identity by eliminating much of the tension between Tommy and his followers. Donna Summer's cover of ‘MacArthur Park’ has a majestic, slow-build-to-big-finish character in its radio version, but loses all but a few chords of its intro, two lines of the first verse (‘between the parted pages and were pressed’ vanishes!), most of a fantasia and the second subject to which it had led, and a chorus. In all of these cases, the differing edits can be considered not only as conforming to different market expectations, but as radical rewrites.

‘Suite: Judy Blue Eyes’, comprising a multi-section form at 7:22 on the album, retains its basic structure in a 4:35 single that remains wide ranging and is surprisingly acceptable despite its five isolated excisions: second verse (‘Remember what we've said …’) and its refrain, all of the third verse (‘Something inside …’), the second B section (‘I've got an answer …’), the second half of the modal guitar solo and the ‘Lacy lilting lady’ section, splicing directly from ‘How can you catch the sparrow?’ into the guitar duet that ushers in the Spanish coda. The 45 is a listenable recording (because entire sections, rather than parts of phrases, are cut), but one that loses much of the brilliance of Stills' emotional exposure. Less successful is the single version of ‘Sunshine of Your Love’, a violent butchering that saves only just over a minute in duration. The engineers here are intent on chopping each guitar/bass lick in half through the intro and following each of the three verses, grounding the proportions that soar on the album cut. Most of the guitar solo is discarded, as is the riff introducing the third verse (‘I'm with you, my love …’). It also fades a few seconds early, but few would notice this loss. The single version of Yes's ‘Roundabout’ skips Howe's unmeasured 40-second-long harmonic-laden nylon-string tastar de corde opening and one of the two hearings of the funky intro. It then cuts from the end of the second subject (‘In and around the lake …’) to the end of the Hammond solo; the remainder is presented uncut. The song's monumental interior, including unique presentations of strong passages, is eviscerated, and yet the edit works surprisingly well as a single, due to the original track's astounding variety of tunes, rhythms and colours.

I would like to close by mentioning four projects in which editors have created a large number of versions from a single source. First is Jethro Tull's A Passion Play (1973). Despite its identity as an indivisible, free-form, full-length magnum opus (as was its predecessor, Thick As a Brick), Tull's management and record executives sought to have segments of it become known as parts of the larger whole. After all, the album, with uninterrupted sides running 23:07 and 22:04, was not radio friendly; even the side-flip broke continuity. Therefore, the album was promoted with two singles. The lead single contained two excerpts, ‘A Passion Play (Edit #8)’ (3:04) backed with ‘A Passion Play (Edit #9)’ (3:29). ‘[Edit #10]’ was released as a follow-up four months later; neither single sold well (‘#8’ peaked at #80; ‘#10’ only bubbled under the ‘Hot 100’), but Chrysalis Records mounted a strong effort in another unusual way to have bits of the work recognised as excerpts. As might be guessed by the singles' numerative titles, these edits were not the only ones to appear: Chrysalis manufactured a unique 12ʺ promo LP featuring 10 different excerpts from the album, ranging in length from 2′15ʺ to 4′58ʺ (see Figure 6). Some of the edits are all-instrumental, some include vocals. Some are oddly conceived: ‘Edit #3’ opens abruptly and ‘#2’ fades out just before an obvious cadence. Strangely, the album's lead single (the ‘Colours like none …’ section from the LP's second side) appears on M.U. – The Best of Jethro Tull with a timing of 3:29 – thus, there are two extant edits of ‘Edit #8’, this second version including a synth solo abridged on the single!Footnote 15 Radio programmers and singles buyers paid little attention to this material, but the album sold remarkably well – in the US, Thick as a Brick and A Passion Play were Tull's only two albums to top Billboard's Top LP chart.

Figure 6. Selected vinyl releases of A Passion Play. (a) Side One of LP; (b) A-side of stock copy of lead single; (c) Side II of DJ album.

A second item of interest is Mike Oldfield's Tubular Bells. This 1974 title, initially well known as the source of the instrumental film theme from The Exorcist, appeared in numerous guises. A heavy layering of overdubs that put multi-track tape through tougher paces than would even Walter Carlos or Tomita, Bells was sold through a stock single of 3:18 (the static, minimalist ‘Georgetown’ theme based on a 15-beat pattern in A Aeolian), the edit also appearing on the soundtrack LP, and through Oldfield's unified-composition Tubular Bells album (whose first-side finale announces the entry of each layer: ‘grand piano … reed and pipe organ … glockenspiel … bass guitar … double-speed guitar … two slightly distorted guitars … mandolin … Spanish guitar and introducing acoustic guitar … plus, tubular bells’, a passage taken for the single's 4:39 B-side). The original promo comprises two other excerpts: ‘Long Version’ (7:30) and ‘Short Version’ (4:39), both taken from the first-side finale section. Despite Oldfield's having produced other memorable music, Tubular Bells has grown from a multiple-edit franchise recording into a highly derivative cottage industry: we have highly similar approaches in Oldfield's The Orchestral Tubular Bells (1975, recapping the original tunes and adding new material), Tubular Bells 2 (1992), Tubular Bells III (1998) and a live DVD (2006).

Meat Loaf's ‘Paradise By the Dashboard Light’ (1978) was essentially an oratorio based on the story of 17-year-olds making out in a parked car, arranged in three sections – ‘Paradise’, ‘Let Me Sleep On It’ and ‘Praying for the End of Time’ – that formed a dramatic highlight on the Todd Rundgren-produced album, Bat Out of Hell. The LP version ran to 8′28ʺ, judged to be a bit too long for a single, so a 7′55ʺ version was created that fades out early in the boy–girl ‘End of Time’ duet. But radio stations were also given a 12ʺ promo disc providing, in a fit of overkill, three edits of the song: the 7:55 hit and two different versions running 6′58ʺ each. The first of this last pair removes the initial ‘Let Me Sleep On It’ duet, fading out a few lines before the 7:55 edit, and the other cuts Phil Rizzuto's risqué play-by-play as well as most of the composition's climax. Really, there is no useful purpose to any of these edits – just play the 8:28 version, already!

Finally, we turn to Sugarhill Gang's ‘Rapper's Delight’ (1979), an alternation of unrelated raps ranging from braggadoccio to snide anecdotes from Wonder Mike, Big Hank and Master ‘G’, each taking several turns. A 15′00ʺ version appearing on a 12ʺ single might be considered the master, as each artist appears three times in turn, and from that we have a stock single at 4:55, a French 45 coupling ‘Short Version’ (3:59) with ‘Long Version’ (6:33) and a second ‘Short Version’ (6:30) backing the 15′00ʺ ‘master’. The edits present different combinations of sections and parts of sections, occasionally reordered. This track is very appropriately drawn and quartered in different ways, as its material comes across as a random sequence of unrelated events.

Our survey of the various methods behind the mixes and edits of pop and rock recordings just scratches the surface of a topic that promises to yield productive results when the work of particular artists, producers, engineers, songwriters, record companies, studios, distribution media, styles and decades is considered from the perspectives outlined here. In addition, the wide range of types of intratextuality and intertextuality suggested in the essay's opening paragraphs could be pursued along the lines demonstrated here for a fuller understanding of the ways in which individual instances and bodies of pop and rock music might be appreciated as multiple interrelated members and subgroups of a larger community, all tying economic and other cultural expectations and needs to specific musical characteristics. The separate miracles of the entertainer writing his song, the bureaucratic exec dictating just the right limits of a marketing tool, a record spinning on the radio, and a major hit transfixing the nation all come together in the star-making machinery of a beautiful and well produced record.