1. Signal processing

Signal processing is modifying an audio signal by inserting a signal processor – that is, a device designed to modify audio signal in particular ways – into the audio chain, and manipulating its adjustable parameters. This practice plays a crucial role in modern rock and electronica. All manner of harmony, rhythm and melody are conveyed to listeners in a processed state on rock and electronica records, and recordists working in both genres are expected to be highly proficient at signal processing. As Kevin Ryan and Brian Kehew (Reference Ryan and Kehew2006, p. 266) explain, the modern rock and electronica recordist now:

has at his fingertips a nearly infinite array of effects. From traditional standbys such as reverbs and delays, to more modern techniques such as convolution and emulation, the selection is endless and – for better or worse – instantaneous. Effects are now a ubiquitous commodity.

It should come as no surprise, then, that makers of rock and electronica records have become basically extroverted in their use of signal processing. Whereas signal processing was once used to preserve the realism of a recorded performance, a majority of rock and electronica records now feature what John Andrew Fisher (Reference Fisher and Alperson1998) calls ‘nonveridic’ or ‘constructive’ applications, which is to say, they do not sound as though they were, or even could be, performed live. Of course, what sounds ‘veridic’ and ‘nonveridic’ varies from time to time and place to place; a ‘veridic’ punk rock production, for instance, will sound totally different from, say, a ‘veridic’ hardhouse track. Moreover, what sounded ‘nonveridic’ decades ago can epitomise ‘veridic’ production values today. What ultimately matters in an analytic sense is that recordists continue to recognise, and make, a fundamental distinction between what they do in the studio and on stage, and that they deploy a variety of signal processing techniques to do so. In Alexander Case's words:

The most important music of our time is recorded music. The recording studio is its principle musical instrument. The recording engineers and music producers who create the music we love know how to use signal processing equipment to capture the work of artists, preserving realism or altering things wildly, as appropriate. … Equalisation is likely the most frequently used effect of all, reverb the most apparent, delay the most diverse, distortion the most seductive, volume the most under-appreciated, expansion the most under-utilised, pitch shifting the most abused, and compression the most misunderstood. All effects, in the hands of a talented, informed and experienced engineer, are rich with production possibilities. (Case Reference Case2007, pp. xix–xx)

Frequency response

It would be reasonable to assume that every audio signal is processed. A number of factors inevitably mediate even the most transparent of audio captures and, thus, every audio signal is rendered such that output (playback) does not exactly match input. The most fundamental of these ‘mediating factors’ is the transducing mechanism itself. Each transducer has a biased way of ‘hearing’ audio information, called its ‘frequency response’.Footnote 1 The easiest way to explain how this bias works is to elucidate some of the more obvious ways that the human ‘frequency response’ mediates whatever it hears.

Adult humans are biologically equipped to process audible information in the range of about 20 Hertz (Hz) to 20 kiloHertz (kHz). Although natural ‘wear-and-tear’ of the ear's component parts allows for almost endless variation in each person's ability to hear within this audible spectrum, and though most adult human beings have difficulty hearing much above 16 kHz anyway, the lower and upper limits of 20 Hz and 20 kHz, respectively, delineate the total expanse of the human ‘frequency response’ – frequencies below 20 Hz and above 20 kHz are actively rejected. The human ‘frequency response’ is furthermore characterised by a pronounced sensitivity to so-called ‘mid-range’ frequencies, particularly those in the 1–5 kHz range (Thompson Reference Thompson2005, pp. 209–10). Human ears typically exaggerate (amplify) the ‘mid-range’ of what they hear, resulting in the perception of more energy between 1 and 5 kHz whether or not that range is objectively predominant. A greater increase in intensity is thus sometimes required to produce ‘louder’ sounding frequencies below 1 kHz and above 5 kHz than is required to produce ‘louder’ mid-range frequencies.

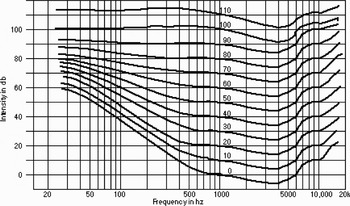

The chart of ‘equal loudness contours’ reproduced in Figure 1, which recordists colloquially call ‘Fletcher–Munson curves’ after the pyschoacousticians Harvey Fletcher and Winfred A. Munson, quantifies discrepancies in subjective loudness within the human ‘frequency response’. These curves use ‘phons’ as their base measure, where 1 phon is equal to the loudness level of a 1 kHz tone played at precisely the same number of decibels. All points on a ‘phon level’ sound equally loud to human ears, even if there are sometimes massive discrepancies in objective volume between them. Thus the human ‘frequency response’ hears, say, 50 decibels of a 100 Hz tone and 30 decibels of an 18 kHz tone as dynamically equivalent to 10 decibels of a 1 kHz tone.

Figure 1. Example of equal loudness contours, adapted from Thompson (Reference Thompson2005, p. 211).

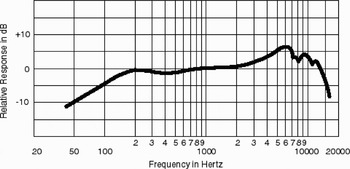

One of the better known ‘frequency response’ contours in the rock world belongs to the Shure SM57 dynamic microphone. Although no two microphones transduce exactly the same, Figure 2 reproduces ‘frequency response’ specifications for the SM57 which Shure provides with each unit in its packaging. Distinguishing traits of its contour include the sharp bass ‘roll-off’ beginning at roughly 200 Hz and the upper-mid-range ‘peak’ centred at about 6 kHz. Just as human ears exaggerate the mid-range (1–5 kHz) and reject everything below 20 Hz and above 20 kHz, so the Shure SM57 sharply attenuates all incoming audio below 200 Hz and above about 13 kHz, exaggerates all sound between roughly 2 and 7 kHz, and rejects everything under 40 Hz and above about 15 kHz.

Figure 2. Frequency response specifications for the Shure SM57 ‘dynamic’ microphone.

Equalisation

Originally used by recordists to compensate for the distorted frequency response of early microphones, equalisers (EQs) adjust the amplitude of the signal at certain frequency ranges. They are, in other words, frequency-specific volume knobs. If a microphone exaggerates, say, the mid-range (1–5 kHz) of incoming audio, recordists may use an equaliser to attenuate all incoming signal in that range, thereby ‘matching’ the recorded sound with its original source. However, as Roey Izhaki explains:

equalisers used today are not employed to make one sound equal to another, but to manipulate the frequency content of various mix elements. The frequency virtue of each individual instrument, and how it [fits within] the overall frequency spectrum of the mix, is a paramount aspect of mixing. Operating an equaliser is an easy affair, but understanding frequencies and how to manipulate them is perhaps the greatest challenge mixing has to offer. (Izhaki Reference Izhaki2008, p. 205)

Recordists typically use five basic kinds of EQ: (i) parametric; (ii) semi-parametric; (iii) graphic; (iv) peak; and (v) program. Though each of these EQs has its fairer features, the parametric and graphic EQ are most common (Toulson and Ruskin Reference Toulson and Ruskin2008). Invented by George Massenburg in 1967, parametric EQs allow users to determine every parameter of equalisation, including: (i) ‘band’, that is, where in the frequency spectrum to equalise; (ii) ‘Q-value’, that is, how much of the frequency spectrum to equalise; and (iii) ‘amount’, that is, the amount of equalisation or the size of the ‘boost’ (amplification) or ‘cut’ (attenuation) to apply (Katz Reference Katz2007, p. 105). A graphic EQ, on the other hand, features only a sequence of fixed bands, and the Q-value of each is typically predetermined. Users of graphic EQs thus choose only the amount of boost or cut to apply to each fixed band, and only as the predetermined Q-value proscribes.

Depth equalisation

A number of equalisation techniques pervade modern rock records. Recordists commonly use equalisation to increase the ‘depth’ of a mix, for instance. Human ears tend to interpret ‘duller’ sounds – specifically, sounds lacking in mid-range and high-end frequency components – as less proximate than sounds with a plethora of such components. In Izhaki's words:

Low frequencies bend around obstacles and are not readily absorbed. High frequencies are exactly the opposite. These are some of the reasons for which we hear more low-frequency leakage coming from within venues. Our brain decodes dull sounds as if coming from further away, a reason for which our perception of depth is stretched when under water. We use this ‘darker-equals-further’ phenomenon to enhance, if not perfect, the front-back impression of various instruments [in a mix]. (Izhaki Reference Izhaki2008, p. 207)

Recordists regularly use this quirk of human hearing to their advantage, introducing equalisation cuts and boosts at select frequencies across a mix to emphasise the high-end components of some tracks, and the bass and mid-range components of others, in order to increase the general impression of depth that a mix creates. Though I do not examine spatial processing (i.e. reverb and delay) in this paper, I should note that the select application of reverb and delay, alongside straightforward volume boosts and cuts, also plays an important role in how mixing engineers construct depth.

The long crescendoing sample that sounds from 0:08 to 0:37 of Eric Prydze's ‘Call On Me’ (2004) provides an instructive example. Comprised entirely of a well known vocal phrase sampled from Steve Winwood's ‘Valerie’ (1982) – specifically, the singer's repeated request for his love-interest, Valerie, to ‘call on me’ – the sample initially sounds with all of its mid-range and high-end frequency components filtered out. Over the course of a 29 second fade-in, Prydze broadens the spectral content, that is, the total frequency content, of the sample until its full bandwidth finally sounds at 0:35, after which point he triggers another sample from the Winwood original – ‘I'm the same boy I used to be’ – and ‘Call On Me’ begins in earnest. Prydze repeats the effect without any accompaniment just over 1 minute later, at 1:49, and again with full accompaniment at 2:31. In all three cases, as the input spectrum broadens, the sample increases in proximity to the listener and, thus, increases the general impression of depth.

Mirrored equalisation

Another common equalisation technique is so-called ‘mirrored equalisation’. This practice entails using EQs to give tracks with similar frequency components complimentary spectral shapes (frequency profiles), recordists ‘carving’ or ‘wedging’ equalisation boosts and cuts at select frequency ranges where instruments would otherwise overlap and compete for audibility. For instance, bass guitar and kick drum usually fight for the same frequency space on rock records, that is, both instruments typically present overlapping frequency components and, thus, compete for audible prominence within those ranges. Moreover, kick drum and bass guitar are often paired in pop productions, meaning that they typically sound at roughly the same times. Recordists thus apply equalisation boosts on the kick track in roughly the same regions they attenuate on the bass guitar, and vice versa. In Izhaki's words:

Say we want to add attack to a kick. Instead of boosting the attack frequency on the kick, we can attenuate the same frequency on masking instruments. In fact, a common technique based on this concept is called mirrored equalisation. It involves a boost response on one instrument and a mirrored [cut] on the other. This helps reduce frequency overlapping, or, masking. (Izhaki Reference Izhaki2008, p. 239)

When applied to tracks spread (panned) to either side of the stereo plane, mirrored equalisation can enhance the perceived width of a mix. Rock engineers often equalise electric guitar parts differently and, when appropriate, they pan the tracks to opposite sides of the stereo spectrum. The distinct spectral shapes that both electric guitars subsequently take prompts listeners to localise a different source of sound for each, located in the extreme left and right periphery, respectively. Applying a very brief delay of, say, 8–25 milliseconds to only one of the two panned tracks further enhances the impression of width this technique can create (Izhaki Reference Izhaki2008, pp. 168–76).

Mirrored equalisation is characteristic of a number of rock productions. However, perhaps the most obvious examples are heard throughout The Strokes' Is This It? LP (2000). Every track on the album features this equalisation and panning device at least once. The most obvious example is ‘Last Night’, track seven on Is This It?, which features an abrupt transition from mono to stereo imaging on the electric guitars after exactly 10 seconds. Throughout the record, in fact, Albert Hammond Jr's and Nick Valensi's guitar parts are ‘mirrored’ and panned either moments before, or precisely when, Julian Casablancas's vocals enter, ‘wedging’ more space into the centre of the mix for Casablancas's vocals to fill in the process. This technique is clearly audible at, for instance, 11 seconds into track six, ‘Alone Together’; 11 seconds into ‘Is This It?’; 14 seconds into ‘The Modern Age’; 7 seconds into ‘Soma’; 10 seconds into ‘Last Night’; and 16 seconds into ‘New York City Cops’.

Dynamics: compressors/limiters and gates

While equalisation reshapes the amplitude of audio signal at select frequencies, most dynamics processors react to and reshape the amplitude of audio signals across the frequency spectrum. They are, in other words, ‘automatic volume knobs’, as Bill Gibson (Reference Gibson2005, p. 5) puts it. Most often, users set a ‘threshold’, usually expressed in decibels, which serves as an automatic trigger for the device. When the amplitude of the input signal registers either above or below that threshold, the dynamics processor either amplifies or attenuates the input signal by a select amount, called the ‘ratio’ or ‘range’, depending on the device used and how it is set. Users can further specify how quickly and for how long they want the processor to work after it has been triggered by setting unique ‘attack’ and ‘release’ times, respectively.

Compressors/limiters

‘A compressor and limiter both operate on the same principle’, according to Bill Gibson:

The only difference between these dynamic processors is the degree to which they affect the signal that exceeds the threshold. Whereas a compressor functions as a gentle volume control – which, normally, should be transparent and seamless to the audio process – a limiter is more extreme, radically decreasing the level of the signal that passes above the threshold. Each of these tools has a distinct and important purpose for the creation of professional sounding audio. … When used [correctly] a high-quality compressor/limiter is transparent throughout the majority of the audio material, while performing important level control during peak amplitude sections. (Gibson Reference Gibson2005, p. 9)

Only making matters more difficult for the inexperienced processor, ‘there is nothing built in to human hearing that makes it particularly sensitive to the sonic signatures of compression’, as Alexander Case notes:

There is no important event in nature that requires any assessment of whether or not the amplitude of the signal heard has been slightly manipulated by a device. Identifying the audible traits of compression is a fully learned, intellectual process that audio engineers must master. It is more difficult than learning to ride a bicycle. It is possible that most other people, including even musicians and avid music fans, will never notice, nor need to notice, the sonic fingerprint of compression. Recording engineers have this challenge all to themselves. (Case Reference Case2007, pp. 161–62)

Compression is comprised of five basic adjustments: (i) threshold; (ii) ratio; (iii) attack; (iv) release; and (v) knee. As noted, compressors feature a threshold which users set to a particular decibel value; the compressor triggers (‘turns on’) whenever the amplitude of the input signal exceeds that value. Once triggered, the compressor attenuates the input signal according to a selected attenuation ratio. If the input signal registers, say, 6 decibels over the selected threshold, and the attenuation ratio is set for 3:1, the resulting ‘compressed’ signal will be only 2 decibels above the threshold – set for a ratio of 3:1, the compressor allows an output of only 1 decibel above the threshold per every 3 decibels above it the input signal registers. A ratio value of 10:1 or higher results in limiting, that is, compressors set to a ratio of 10 + :1 limit the dynamic range of a signal such that its transient peaks never exceed a selected level, though most recordists use a dedicated limiter to achieve this effect nowadays. Compressors thus compress the distance between a waveform's peaks and valleys, which is to say, they compress the dynamic range of audio signal, while limiters limit the peak amplitude of audio signal to an absolute decibel value.

As noted, compressors allow users to set ‘attack’ and ‘release’ times which specify, respectively, when the compressor should begin to attenuate the input signal after the threshold is breached, and for how long it should continue to do so after the signal subsides. Related to this, compressors typically feature a ‘knee’ setting, which specifies how sharply the compressor will attenuate and release once it triggers. In Gibson's words:

Hard knee/soft knee selection determines how the compressor reacts to the signal once it passes [the] threshold. Whereas the ratio control determines the severity of compression, the knee determines how severely and immediately the compressor acts on that signal. When the compressor is set on soft knee and the signal exceeds the threshold, the amplitude is gradually reduced through the first 5 dB or so of gain reduction. When the compressor is set on hard knee and the signal exceeds the threshold, it is rapidly and severely reduced in amplitude. (Gibson Reference Gibson2005, p. 28)

Pumping

Compression is easiest to hear when it is creatively misused. The most common, and obvious, misuse produces what recordists call ‘pumping’, that is, ‘audible unnatural level changes associated primarily with the release of a compressor’ (Izhaki 2008, p. 160). While there is no single correct way to produce pumping – Case (Reference Case2007, p. 160), for instance, notes that the effect can be a result of selecting ‘too slow or too fast … or too, um, medium’ attack and release settings – pumping usually happens when recordists fail to assign a long enough release time to adequately handle a decaying signal. As Case explains:

One of the few times compression can be clearly heard, even by untrained listeners, is when it starts pumping. … The audio signal contains material that changes level in unexpected ways. It might be steady-state noise, the sustained wash of a cymbal, or the long decay of any instrument holding a note for several beats or bars. Listeners expect a certain amplitude envelope: the noise should remain steady in level, the cymbals should slowly decay, etc. Instead, the compressor causes the signal to get noticeably louder. This unnatural increase in amplitude occurs as a compressor turns up gain during release. (Case Reference Case2007, p. 160)

Pumping is now a common technique in rock and electronica. House, hardhouse, microhouse, techno, IDM and glitch records all regularly feature the technique, as do tracks by modern rock bands like Radiohead and, periodically, The Strokes. Flying Lotus' 1983 (2006) and Los Angeles (2008) are chock full of examples, although readers may find it easier to hear the technique at work in a top 40 rock production rather than in experimental hip hop and IDM. Phil Selway's drum track for Radiohead's ‘Exit Music (For A Film)’ (1996) provides a celebrated example. From the time they enter at 2:51, Selway's drums are increasingly compressed to the point of pumping; and pumping is particularly audible on the cymbal-heavy portion of Selway's performance from 3:20 to 3:36. In fact, the cymbal crash which sounds from 3:26 to 3:28 of ‘Exit Music (For A Film)’ pumps so dramatically and so obviously that producer Nigel Godrich may as well have foregone the compressor and simply automated a volume swell on the cymbals using a parametric or graphic EQ. Pumping is also clearly audible on the electro beat which underpins Radiohead's ‘Idiotheque’ (2000), track 8 from the band's controversial Kid A LP (2000), especially in the wild dynamic fluctuations that characterise the snare drum's sustain and release profile after the entrance of the sampled pads at 0:11. Pumping is likewise clear on the ride cymbals throughout Portishead's ‘Pedestal’ (1994), track nine on their trip hop breakthrough, Dummy (1994).

Side-chain pumping

A more advanced, if heavy-handed, application of dynamics processing entails use of a compressor's ‘side-chain’ feature. A compressor's side-chain uses the amplitude envelope (dynamics profile) of one track as a trigger, even as it functions in the audio chain for another. Applied to, say, a synth pad, a compressor side-chained to a kick drum playing regular ‘four-on-the-floor’ quarter-notes will attenuate the pad when the amplitude of the kick surpasses its threshold, producing a sequence of quarter-note volume swells offset from each iteration of the kick by a selected ‘release’ time. The result is something similar to the kind of pumping considered above, but side-chain compression fluctuates according to the amplitude of another track and regardless of the properties of the attenuated track.

Side-chain pumping has found a special place in the hearts of house, hardhouse, microhouse, techno, IDM and glitch recordists lately. However, Eric Prydze's ‘Call On Me’ is largely credited with having popularised the technique, even if Daft Punk's ‘One More Time’ (2001) could easily make a claim for that honour. ‘Call On Me’ features obvious side-chain compression on the synth pads whenever the kick drum sounds (0:00–0:25, 0:37–0:50, 0:52–1:03, 1:08–1:19, 1:30–1:45 and 2:16–2:42) and a conspicuous absence of side-chain compression whenever the kick drum is tacit (0:26–0:37, 0:51–0:52, 1:03–1:08, 1:19–1:30, 1:46–2:16 and 2:43–3:00). The pumping effect is clearly audible during the first 10–15 seconds of the track, when only the kick drum and a synth pad sound in tandem, but it is also abundantly clear in subsequent sections, especially from 0:39 to 1:50.

Another clear example of side-chain pumping can be heard on Madonna's ‘Get Together’ (2005), track two from her Confessions on a Dance Floor LP (2005). During the song's 38-second introduction the amplitude envelope of the synth pads remains constant, which makes the pumping that sputters in on those pads with the entrance of the kick at 0:38 all the more obvious. Finally, the synth arpeggios which sound between 1:28 and 1:55 of Benny Benassi's ‘My Body (featuring Mia J)’ (2008) are also instructive. From 1:28 to 1:42 the kick drum sounds the obligatory ‘four-on-the-floor’ pulses, and the side-chained compressor on the synth follows dutifully along; between 1:42 and 1:55, however, the kick is tacit and the synth part repeats completely unattenuated.

Gates

As compressors attenuate signal which registers above the threshold, gates attenuate signal which registers below the threshold. Unlike compressors, however, gates attenuate signal by a fixed amount, called ‘the range’. Recordists usually use a gate to reduce the input signal to silence at quiet intervals, which can require a ‘range’ of more than 80 decibels of immediate reduction, though the device has plenty of other established uses. Aside from attack and release settings, gates also typically feature a ‘hold’ setting, which determines the length of time – typically anywhere from 0 to 3 seconds – the gate remains ‘turned on’ once the signal which triggered it has subsided under the threshold. Most gates also feature a ‘look-ahead’ function, which delays the input signal by millionths of a second so the gate can examine its amplitude and determine a ‘soft’, that is a gradual, response to any portions requiring attenuation.

Though gates are often used for ‘troubleshooting’ – specifically, to remove background noise from the quieter portions of noisy tracks – they also have their creative misuses. One of the best known misuses for gating is the so-called ‘gated-reverb’ effect, which producer Steve Lillywhite and engineer Hugh Padgham famously used to create Phil Collins' massive drum timbre on Peter Gabriel's ‘Intruder’ (1980). Recorded in a cavernous barn with microphones distributed throughout at strategic intervals chosen to best capture the kit's ambient reflections, the resulting drum part was compressed first and then gated. Lillywhite and Padgham used compression to ensure that the drum hits and their ambient reflections sounded dynamically equivalent, the usual amplitude envelope of a top 40 drum kit in this case superseded by a cavernous, elongated decay and sustain profile; while the gate truncated the release profile of each compressed hit, ensuring an almost instantaneous transition from sound to silence. As Albin Zak explains:

The effect in this case is one of textural clarity. … The gated ambience on the drums resolves a physical contradiction: it evokes the size associated with large, open ambient spaces while at the same time confining the sound to a clearly delineated place in the track. Limiting each eruption of sonic intensity to a short burst solves the problem of preserving textural clarity without diminishing the ambient drums' visceral power. … With the ambient decay continuously truncated, there is a sense of things being always interrupted, of their natural course being curtailed and controlled by a dominating force. And the strange behaviour of the sound in this atmosphere dictates the terms of our acoustic perception. Because it makes no sense in terms of our experience of the natural sound world, rather than perceiving the ambience as space, we are reoriented to hearing it simply as an extension of the drums' timbre. (Zak Reference Zak2001, pp. 80–81)

Another celebrated ‘misuse’ for gating can be heard on David Bowie's ‘Heroes’ (1977), track three on the middle record from his and Brian Eno's so-called ‘Berlin Trilogy’. ‘Heroes’ tells the story of a doomed couple from either side of the Berlin Wall, whose clandestine meetings Bowie claimed to have observed from the windows of Hansa By The Wall Tonstudio while he, Eno and producer Toni Visconti recorded there; the track features a number of quirky production techniques which have become the stuff of legend for subsequent generations of rock recordists. Likely the most celebrated of these quirks is the treatment Visconti devised for Bowie's vocals. Visconti tracked Bowie's vocals using a system of three microphones distributed variously throughout Hansa's cavernous ‘live’ room, specifically, at a distance of 9 inches, 20 feet and 50 feet, respectively. Applying a different gate to each microphone, Visconti ensured that signal made it through to tape only when the amplitude of Bowie's vocals became sufficiently loud to overtake each gate's threshold. Moreover, Visconti muted each microphone as the next one in the sequence triggered on. Bowie's performance thus grows in intensity precisely as ever more ambience infuses his delivery, distancing the singer from listeners and, eventually, forcing him to shout just to be heard.

Keyed gating: envelope following

Just as compressors can ‘side-chain’ to a different track from the one they attenuate, so too can gates ‘key’ to another track from the one they attenuate. Keyed to a vocal track, for instance, a gate on an electric guitar part will only ‘open’ to allow sound through when the amplitude of the vocal track surpasses its threshold. One of the more obvious, and creative, modern uses for keyed gating produces ‘envelope following’, that is, the deliberate refashioning of one amplitude envelope either to match or, at the very least, to closely imitate another. This technique has become particularly popular in modern electronica productions, especially on trance records. As Alexander Case explains:

Insert a gate across a guitar track, but key the gate open with a snare track. The result is a guitar tone burst that looks a lot like a snare, yet sounds a lot like a guitar. This kind of synthesised sound is common in many styles of music, particularly those where the sound of the studio – the sound of the gear – is a positive, such as trance, electronica, and many other forms of dance music (always an earnest adopter of new technology). A low-frequency oscillator, carefully tuned, can be keyed open on each kick drum for extra low end thump. Sine waves tuned to 60 Hz or lower will do the job. Distort slightly the sine wave for added harmonic character or reach for a more complex wave (i.e. a saw tooth). The resulting kick packs the sort of whollup that, if misused, can damage loudspeakers. Done well, it draws a crowd onto the dance floor. (Case Reference Case2007, pp. 184–85)

Imogen Heap makes creative use of this technique on her breakout hit, ‘Hide and Seek’ (2005). Heap's production for the song is remarkably sparse, given how lushly orchestrated the track sounds on first blush. Sung into a Digitech Vocalist Workstation harmoniser, Heap's lead vocals and a few overdubbed vocalisations provide the song with its only melodic content; meanwhile the harmoniser, set in ‘vocoder mode’, automatically fills in the song's vocoded background harmonies using the pitches that Heap played on a connected keyboard while she sang. Keyed to Heap's vocal line, the gate on the harmoniser only opens when Heap sings, and it abruptly attenuates the signal to silence during each pause in her delivery. The effect is strangely unsettling, as though a chorus of synthesisers were ‘singing along’ with Heap, leaving only the odd bits of reverb and delay to trail off into the periodic silences.

Keyed gating: ducking

Another common use for keyed gating is to ‘duck’ the amplitude of one signal under another, that is, to make one track quieter whenever another gets louder. To achieve this effect, recordists insert a modified gate – e.g. a gate with its ducking function engaged – into the audio chain of whichever track they want to attenuate, and they key that gate to the track they want to sound louder; otherwise, they insert a dedicated ducker directly into the audio chain of the track they want to attenuate. Whenever the amplitude of the ducking signal registers above the selected threshold, the ducker attenuates the signal it ducks by a fixed amount (‘range’). As Roey Izhaki explains:

Say we want the full slap of the kick but the distorted guitars mask much of it. We can reduce this masking interaction by ducking the distorted guitars whenever the kick hits. It can be surprising how much attenuation can be applied before it gets noticed, especially when it comes to normal listeners. Whether done for a very brief moment, or for longer periods, ducking is an extremely effective way to clear some space for the really important instruments. Indeed, it is mostly the important instruments serving as ducking triggers and the least important instruments being the ducking prey. (Izhaki Reference Izhaki2008, p. 377)

The most often cited example of ducking is its broadcast application – ‘when the DJ speaks, the music is turned down’, summarises Roey Izhaki (Reference Izhaki2008, p. 374). However, one of the most common ducking techniques used on rock and electronica records today is to duck reverb and delay processing under ‘dry’ (untreated) vocal tracks. As noted with regards to ‘Heroes’, the more ambience pervades a track the more ‘dulled’ it becomes, which is to say the less clear its attack transients sound and, in turn, the more likely listeners are to interpret the track as being muffled and distant. Returning once more to Alexander Case:

When sound travels some distance in a room, the high-frequency portion of the signal is attenuated more quickly than the low-frequency part. High-frequency attenuation due to air absorption is an inevitable part of sound propagating through air. As a result … the brain seems to infer the air absorption and perceptually pushes the sound away from the listener. (Case Reference Case2007, p. 226)

Recordists can combat this effect by inserting a ducker into the reverb and delay line, keyed to whichever track the reverb and delay process. The ‘dry’ track thus ‘ducks’ its own reverb and delay, that is, the reverb and delay is notably attenuated each time the amplitude of the ‘dry’ track exceeds the ducker's threshold.

A clear example of this effect can be heard on Céline Dion's ‘The Power Of Love’ (1993). Produced by fellow Canadian David Foster, ‘The Power Of Love’ has all the hallmarks of a Dion track from the early 1990s – each detail of Foster's production is geared to showcasing Dion's trademark ‘massive’ vocals, which range from a whisper to straightforward belting numerous times throughout the song. The ‘ducking’ effect is most obvious during the first verse and chorus, however, as the lush reverb and delay on Dion's vocals swell to the fore each time she pauses. The end of the first vocal line in the first chorus – ‘because I'm your lady’ – provides the song's clearest example, as the echoing delay and the lush reverb on Dion's vocals swell to audibility the very second she stops singing. Interestingly, as the song progresses and Foster's layered arrangement becomes increasingly dense, the ducking effect becomes less pronounced; by the second verse, at 1:23, Foster has dispensed with the delay on Dion's vocals completely, though the reverb remains constant, and ducked, throughout the song.

Keyed gating: ducking systems

The only limitation on what can be ducked, and how ducking should be done, exists in the imagination of recordists. Any track can duck any other track, so long as both tracks contain sufficient amplitude. To combat masking, for instance, some recordists forego the ‘mirrored equalisation’ technique discussed above and, instead, duck the bass guitar under the kick drum. This produces a subtle side-chain pumping effect which effectively ‘clears space’ for the kick drum, but only whenever it and the bass guitar sound in tandem. Similarly, recordists working in the ‘heavier’ rock genres will often duck rhythm guitar parts under lead lines; and, in most genres of electronic dance music, recordists will sometimes duck everything under the kick and snare, though this is most often done using side-chained compressors, as I note above.

Some recordists go even further, however, creating ‘ducking systems’ whereby one track ducks another track which in turn ducks another track, which is set to duck another track, and so on. This ‘systems’ approach to ducking produces a sequence of pronounced dynamic fluctuations that seem to flex randomly, even as they follow the internal logic of the ducking system. Portishead's ‘Biscuit’ (1994) provides an illustrative example. The main 8-second sample which underpins the track, audible in its entirety from 0:12 to 0:20, features at least the following ducking sequence during its first iteration: (i) the opening kick, on the downbeat of bar one, ducks everything but the Fender Rhodes; (ii) the second kick, which sounds like it is accompanied by some kind of sub-bass, on beat two, ducks everything which precedes it, including the vinyl hiss, the Fender Rhodes, and the resonance of the first kick and snare hit; and (iii) the second snare hit ducks everything which precedes it. This opening sequence is simply the most obvious; numerous other, less overt ducking sequences occur throughout ‘Biscuit’.

Conclusion

This field guide is by no means exhaustive. However, the techniques I survey in it recur constantly in modern rock and electronica productions. Depth equalisation, mirrored equalisation, pumping, side-chain pumping, envelope following, ducking and numerous other equalisation and dynamics processing techniques have become as foundational in modern rock and electronica as power chords and tapping once were in heavy metal. Yet they remain conspicuously absent from most research on the rock and electronica genres.

Lacunae are to be expected in a field as young and diffuse as popular music studies. That said, the present paucity of research on specific signal processing techniques signals the institutional basis of popular music studies much more than the field's nascent state, in my opinion.Footnote 2 Numerous insightful and challenging analyses of the record-making process have indeed been published.Footnote 3 However, these studies typically address the analytic priorities and concerns of disciplines which are not primarily interested in musical technique per se – such as cultural studies, sociology, media studies, cultural anthropology and political economy – and, as such, signal processing usually fails to register in them as a fundamentally musical concern. A straightforwardly technical perspective on signal processing has only very recently begun to emerge in the field, as the taboo on studying popular music (and, thus, pop recording practices) which once gripped university music departments slackens.

Even as musicologists and music theorists turn their analytic attentions to pop records, however, and even as many are compelled to reject what David Brackett (Reference Brackett1995, p. 19) calls the ‘ideological and aesthetic baggage’ of ‘musicological discourse’ to do so, they remain largely fixated on musical details which can be notated – formal contour, harmonic design, pitch relations, metered rhythm and so on. No matter how avant-garde their methods, in other words, many analysts still typically fixate on the very same musical details that musicologists and music theorists traditionally analyze. Recording practice itself – that is, the material uses for recording technology which recordists deploy each time they make a recorded musical communication – only registers in a small, albeit growing, collection of articles and books.

‘By now, there is a widespread consensus that pop records are constructed artworks, which has begun to suggest a growing slate of questions about compositional techniques and criteria’, notes Albin Zak:

Scholars have their own traditions and it is reasonable to seek help in answering such questions from older compositional practices with long histories of thought and articulated principles. But since such traditions developed in a pre-electric era where the enabling technology was limited to musical notation, we must also imagine new approaches to criticism and analysis that move beyond the customary concerns of musicologists and music theorists. … Among the problems inherent in establishing an academic discipline aimed at illuminating record production, then, is the need for a fundamental aesthetic reorientation as well as new modes of analytic description. (Zak Reference Zak2007)

Whatever form this ‘aesthetic reorientation’ finally takes, if analysts are to recognise, and make sense of, the particulars of recorded musical communications, signal processing will have to become an even more central analytic concern than it is today. ‘Records are both artworks and historical witnesses’, Zak (Reference Zak2001, p. 23) elsewhere explains. ‘In short, they are all that they appear to be.’ As should now be clear, signal processing plays a fundamental role in shaping that appearance. It is my ultimate hope that this field guide has helped analysts of all disciplinary backgrounds and expertises hear it do so even just a little more clearly.