Introduction: a dialectic encounterFootnote 1

Amadou and Mariam's internationally acclaimed album Dimanche à Bamako (2004),Footnote 2 meaning ‘Sunday in Bamako’, produced ‘by and with Manu Chao’ is the product of an unlikely encounter (see Figure 1). The Malian husband-and-wife duo Amadou Bagayoko and Mariam Doumbia have been writing light-hearted love songs and danceable Afro-pop tunes since the late-1970s, taking their inspiration from amorous French chanson, American rock ‘n’ roll, West African praise-singing, and bluesy Malian guitar music. Franco-Iberian musician Manu Chao has been pushing the boundaries of ‘alternative’ and ‘world’ music since the mid-1980s, mixing punk rock, reggae, ska, North African raï, Latin American folk traditions, and minimalist electronica with incisive lyrical critiques of globalisation and political violence in the Global South. On the surface, their musical interests and expressions present clear differences.

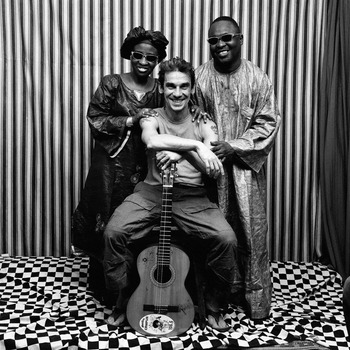

Figure 1. The cover of Amadou and Mariam's recording Dimanche à Bamako (2004) (Marie Dagnaux).

Political concerns are conspicuously absent from Bagayoko and Doumbia's sentimental repertoire, though a general concern for socio-economic problems in sub-Saharan Africa does inform their work (Bagayoko and Doumbia Reference Bagayoko and Doumbia1998, Reference Bagayoko and Doumbia1999, Reference Bagayoko and Doumbia2002).Footnote 3 By contrast, global political activism is essential to Chao's hybrid, cosmopolitan and folkloric aesthetic (Chao Reference Chao2000, Reference Chao2001, Reference Chao2002, Reference Chao2007). Yet, the unique blend of playful poetics and sober politics on Dimanche à Bamako makes for a compelling artistic dialogue, one that Bagayoko, Doumbia and Chao seem eager to cultivate. ‘Mali is a country of exchange’, Chao says. ‘There is always a tendency there to listen, to appreciate what comes from the outside, and to mix the two cultures, the different ways of seeing things’ (Brown Reference Brown2005, p. 32). Emerging from this exchange, Dimanche à Bamako presents a sometimes sentimental, sometimes severe portrait of the Malian capital, Bamako, a city of over one million people sprawling along the upper Niger River, in an era of rampant globalisation. On the album, as in the world, Bamako is familiar and foreign, proximate and distant, civil and wild all at once.

In this article, I am interested in how Dimanche à Bamako musically renders, through sound and lyrical expression, the tensions of what may be called ‘global modernity’ in Africa and its postcolonial diaspora. On the album, these ‘tensions’ manifest in sentiments of celebration and cynicism, love and loathing, cast in a world caught between personal desires for family cohesion and community development and the dehumanising demands of corrupt politics and an inequitable economy. James Ferguson writes, ‘global modernity is characterized not by a simple, Eurocentric uniformity but by coexisting and complex sociocultural alternatives’. He asserts that the ‘successful negotiation’ of these alternatives ‘may hinge less on mastering a unitary set of “modern” social and cultural forms than on managing to negotiate a dense bush of contemporary variants in the art and struggle of living’ (Ferguson Reference Ferguson1999, pp. 251–2). By framing these tensions and alternatives in the context of a modern African city, Dimanche à Bamako offers a theoretically sophisticated representation of urban social space that, while rooted in a particular place (Bamako), attends to the wider world in which a local sense of place gives way to the wanderlust and anxieties of ‘the art and struggle of living’ in a globalised world.

My interpretation of the urban social spaces represented on Dimanche à Bamako builds primarily on the social thought and theory of the Mande world, the West African cultural group to which Bagayoko and Doumbia belong and from which their music emerges.Footnote 4 (Asked about their musical influences in press interviews, Bagayoko and Doumbia rattle off a number of rock and roll icons – Pink Floyd, Led Zeppelin, Deep Purple, Jimi Hendrix – in addition to Cuban dance music, French chanson, and R & B broadcast on Radio Mali in the 1960s and 1970s. When pressed on the type of music they play, however, they are more concise: ‘Bambara’, they say, referring to the predominant Mande sub-group in central and southern Mali [see Krukowski 2005]). On a conceptual level, Mande social space is divided between civil space, centred on family compounds (luw) of which the city (dugu) is composed, and wild space (kungo) lying beyond the boundary of the city (dankun) and its surrounding fields (forow) (see Figure 2).Footnote 5 Broadly, it is the movement between civil and wild spaces that creates friction, dynamism, conflict, and creativity in Mande society (see Bagayogo Reference Bagayogo1989), and it is precisely this movement that Dimanche à Bamako elucidates.Footnote 6

Figure 2. Mande social space.Footnote 7

I begin my essay with a theoretical reflection on the dialectic nature of the album's representation of social space, in which I offer a Lefebvrian reading of the Mande spatial paradigm outlined above. Henri Lefebvre's tripartite model of social space (1991) – made up of what he terms ‘lived’, ‘conceived’, and ‘perceived’ space – is both consonant with and helps to elucidate the structural and processual character of Mande social space represented on the album. Mande socio-spatial thought, in turn, helps to clarify and focus the conceptual density of Lefebvre's theoretical work. I flesh out this hybrid, Mande and Lefebvrian socio-spatial model by examining the musical collaboration developed by Bagayoko, Doumbia and Chao from which representations of social space on Dimanche à Bamako derive their meaning. I do this by putting the artists' personal and professional histories in dialogue with the opening tracks, ‘M'bifé’ and ‘M'bifé (Balafon)’, which, I argue, introduce the dialectic ethos for the album as a whole, oriented around contrasting themes of intimacy (civility) and itinerancy (wildness). Applying this syncretic ethos of socio-spatial dialectics, I present a close reading of three pairs of songs from Dimanche à Bamako.

The first pair, ‘Taxi Bamako’ and ‘Camions Sauvages’ (‘Wild Trucks’), constitutes the narrative and analytic centre of my analysis by giving musical shape and lyrical substance to the socio-spatial dialectics I am proposing. Further, the personal narratives embedded in each song elucidate the fraught character of urban African subjectivity, torn between the expectations of civility and the exigencies of wildness in everyday life. In the next pair, ‘La Réalité’ (‘The Reality’) and ‘Sénégal Fast Food’, I turn to the way these African renderings of urban space and subjectivity map onto global experiences of travel and diaspora. This is where civil space (dugu, meaning ‘town’ or ‘city’) indexes a sense of diasporic community and wild space (kungo, meaning ‘wilderness’ or ‘the bush’) points to the hardships of life abroad in the West. Together, these two pairs of songs, along with the first two tracks discussed below, illustrate the way Dimanche à Bamako represents those who daily cultivate and negotiate the contested – civil and wild – spaces of urban Africa and its diasporas.

I conclude by examining a final pair of songs, ‘La Fête aux Village’ (‘The Village Party’) and ‘Beaux Dimanches’ (‘Beautiful Sundays’), which present a kind of hopeful synthesis of civility and wildness, spaces previously described in apparently irreconcilable opposition to each other. Together, these songs express what I am calling ‘a civil space of global modernity’. Placed on either end of what may be the album's most menacing portrayal of contemporary wildness, ‘Camions Sauvages’, the tracks feature rich neighbourhood soundscapes, wistful and celebratory lyrics, sweet melodies, and cool and cadenced rhythms. Both songs call people together for common celebration, despite the ‘sad realities’ of global modernity, a message of hope and communal affection achieved both on the level of lyrical expression and recorded sound. ‘Beaux Dimanches’ (for which the album is named) is a particularly elegant expression of this synthesis, showing how the civil pleasure of human sociability – rendered musically – can transcend life's wild struggles.

Conceived and lived, wild and civil space

Before elaborating on the particular representations of Mande social space in Dimanche à Bamako, it is necessary to consider the nature of social space in general. For this, I turn to the tripartite model of socio-spatial production outlined by Henri Lefebvre in The Production of Space (1991). This move is important for two reasons: first, because I am positing a globalised extension of the Mande spatial paradigm, articulating dialectically between civil and wild space at home and abroad, it is necessary to find a theoretical language that speaks to the global character of social space, relevant to a world of transnational migration, diaspora formation, and socio-economic globalisation; second, by putting a circumscribed ‘ethno-theoretical’ logic in dialogue with a more generalised expression of Western social thought and theory, I hope to both enrich the descriptive and analytic vocabulary the two systems individually encompass and demonstrate the epistemological consonances between apparently disparate conceptions of social space. While my choice of these two systems of socio-spatial theory is conditioned by the particular nature of my academic research and training, I do believe there are strong conceptual resonances between the two, making their juxtaposition and mutual application less arbitrary and subjective, as I will show.

Lefebvre's tripartite model differentiates between what he calls ‘conceived’, ‘lived’, and ‘perceived’ space (Lefebvre Reference Lefebvre1991, pp. 38–40).Footnote 8 Lefebvre describes conceived space as ‘the space of scientists, planners, urbanists, technocratic subdividers and social engineers, as of a certain type of artist with a scientific bent’ (ibid., p. 39). In other words, conceived space refers to the strategic and formal ordering of space.Footnote 9 On Dimanche à Bamako, these conceived spaces manifest in songs about political authority (‘La Paix’, ‘Politic Amagni’), urban (dis-)order (‘Taxi Bamako’, ‘Camion Sauvages’), and the political economy of global modernity (‘Sénégal Fast Food’, ‘La Réalité’). For Lefebvre, as for the artists and producers of Dimanche à Bamako, conceived space tends toward the production of abstract space, a space characterised by: authoritarian rule; alienation from nature, labour, society, and history; the capacity for arbitrary application of violence; the decline of cultural works in the arts; and the loss of indigenous lifeworlds through the extension of global capitalist systems (ibid., pp. 49–52). This description of ‘abstract space’ is strikingly similar to recent characterisations of African postcolonies (Bayart et al. Reference Bayart1999; Mbembe Reference Mbembe2001; Comaroff and Comaroff Reference Comaroff and Comaroff2006) and directly illustrates the conception of ‘wildness’ expressed in Dimanche à Bamako. This rapprochement of ‘wildness’ and ‘postcoloniality’ is significant. As I describe below, the wild spaces represented on the album emerge in part from relations between a former colony (Mali) and metropole (France), articulated through inherently postcolonial struggles of global modernity, such as transnational migration.

In contrast to conceived space, lived space is ‘the space of inhabitants’ and ‘users’. It describes the tactical and informal use of space. While lived space generally operates outside the formal, prescriptive logics of conceived space (in the privacy of domestic space, or on the social margins of state control), it remains subject to the latter's social and material prohibitions. Yet, lived space is also characterised by the creative manipulation of the forms and structures of conceived space. In Lefebvre's words, lived space makes ‘symbolic use’ of the ‘objects’ of conceived space ‘which the imagination seeks to change and appropriate’ (Lefebvre Reference Lefebvre1991, p. 39). On Dimanche à Bamako, lived space figures in songs about intimacy and betrayal (‘M'bifé’, ‘Djanfa’, ‘Gnidjougouya’), rural and urban ceremonies and rituals (‘La Fête au Village’, ‘Beaux Dimanches’), social and political solidarity (‘Coulibaly’, ‘La Paix’), the value and difficulties of artistic expression (‘Artistiya’), and the nature of everyday sociability (‘Taxi Bamako’). Using the language of Mande socio-spatial thought, lived space represents the civil counterpoint to the dehumanised abstractions, or wildness of conceived space.

Lefebvre's generally pessimistic vision of the diminishing vitality of lived space in the face of ever-expanding systems of abstract, conceived space in the context of late-capitalism is pertinent to the socio-spatial representations in Dimanche à Bamako. As I discuss in my analyses of ‘Camions Sauvages’, ‘La Réalité’, and ‘Sénégal Fast Food’ below, the album evokes a real sense of socio-economic menace from what I am calling ‘the wildness of global modernity’, exemplified by an uncertain urban infrastructure, an unjust global economy, and a corrupt, repressive, and alienating post-/neo-colonial politics. Lefebvre's language of ‘abstraction’ together with his late-capitalist conception of lived space – what Ferguson describes as the ‘art and struggle of living’ in global modernity – productively pushes Mande notions of wild and civil space into a modern world of globalisation, neo-liberalism, and postcolonial political economic relations. Though, as expressions of civility of intimate social relations portrayed on tracks like ‘M'bifé’, ‘Taxi Bamako’, ‘La Fête au Village’, and ‘Beaux Dimanches’ indicate, Mande conceptions of civil space offer a more hopeful vision of lived space than the image of modern socio-cultural decline implied in Lefebvre's work. In Dimanche à Bamako, social space is celebrated as much as it is cause for anxiety, so it is through the celebratory and anxious tensions of social space that the meaning of the album articulates. I will now consider how those tensions are introduced.

Intimate sounds and sentiments

Dimanche à Bamako begins with the strumming of an acoustic guitar and a child's voice on the song ‘M'bifé’. ‘Amadou et Mariam, bonjour’, says the boy named Mamadou. ‘Comment allez-vous?’ (‘How are you?’) The guitar (presumably Chao's) gently rocks between C major and A minor chords, sounding a sort of modal melancholy as an electric guitar (presumably Bagayoko's) lightly picks out the intervals of the chords, occasionally hammering on and pulling off on the second fret of the G and D strings to create bluesy passing tones. After lingering on the A minor for a measure, Manu Chao's slightly coarse and nasal voice enters, singing a low ‘whoa’ over the song's two chords. Light percussion from a pair of tablas joins him. Then, Mariam Doumbia's soulful mezzo-soprano sings the following lines twice, in a mix of French and Bamana: ‘Chéri ne b'i fè / Kana taa ka ne to’ (‘Dearest, I love you / Don't leave without me’). Another layer is then added in the mix with the light, warbling sounds of Mande music veteran Cheick Tidiane Seck's organ. ‘Kana ne maloya’ (‘Don't bring shame upon me’), sings Doumbia. As the overall volume of the musical mix increases, with the percussion, organ, and chorus coming into dramatic relief, Doumbia implores her lover: ‘Serre-moi dans la main’ (‘Hold my hand’), ‘Embrasse-moi chéri’ (‘Hold me, [my] love’). As the song rides over its climax, she repeats her affectionate refrain, now in French: ‘Chéri, je t'aime’ (‘Dearest, I love you’).

Bagayoko and Doumbia first met in the mid-1970s at Bamako's Institute for the Young Blind (both lost their sight early in their lives) where they were members of the Institute's Eclipse orchestra. At the time, Bagayoko had achieved local renown as a teenage guitarist for the legendary Bamako band, Les Ambassadeurs du Motel. Doumbia, who gave voices lessons at the Institute, had been singing at local weddings since the age of six, drawing inspiration from such singers as Fanta Damba, Mokontafé Sacko, and Sira Mory Diabaté. At the Institute, they discovered a common passion for music and each other. As political and economic conditions worsened in their native Mali under the military dictatorship of Moussa Traoré (1968–1991), Bagayoko and Doumbia (now married) relocated to Abidjan, capital of neighbouring Côte d'Ivoire and home to a vibrant popular music scene in the 1970s and 1980s. There, they established themselves as ‘Amadou and Mariam’, known locally as ‘the blind couple from Mali’.Footnote 10

A quarter-century later, their shared personal and professional career, now based in Paris with major record label contracts, continues. Says Bagayoko: ‘We still love each other, and we want to share our happiness with everyone. Many things bring us together: the music, the children, [and] the handicap. We always find a way to get along. The strength of our marriage surprises people in Europe and Africa. In twenty-five years, we haven't been separated for more than a week’.Footnote 11 The song ‘M'bifé’, which in Bamana means ‘I love you’, exemplifies the twining of Bagayoko and Doumbia's musical and marital lives, where sweet, simple melodies and tender lyrical sentiments go hand in hand. The song is reminiscent of their first international hit, ‘Je Pense à Toi’ (‘I'm Thinking About You’) from Sou Ni Tile (Night and Day), released on EmArcy France in 1998. In it, Bagayoko sings plaintively, ‘Ne m'abondonne pas, mon amour, ma chérie’ (‘Don't abandon me, my love, my dearest’), a line echoed by Doumbia in ‘M'bifé’. ‘Don't leave without me’, she sings. The resistance to separation and distance and the intense longing for togetherness and intimacy communicated by these two songs, what Tom Cheyney of La Weekly describes as the couple's ‘heartache-on-the-verge-of-heartbreak mode’ (2005), resonates strongly with the Mande social concept of ‘badenya’.

Badenya, literally meaning ‘mother-child-ness’, denotes the shared affection felt by children of the same mother in polygamous families and connotes devotion to home, family, and tradition. As a social concept, badenya conveys a sense of community, social solidarity, and shared intimacy that is the inter-subjective essence of civil space. As such, badenya carries with it a strong moral valence; there is an essential ‘goodness’ and ‘rightness’ to the familial collectivity badenya implies. The musical portrayal of badenya in ‘M'bifé’ begins with a young boy greeting his elders, an important gesture of respect in Mande society, spoken over a leisurely strummed and picked accompaniment that sounds like a pair of friends jamming in the calm of a neighbourhood courtyard. Chao's chorus, along with the guitars, organ and percussion support Doumbia's song and give a musical impression of social solidarity, with her voice resting on a well-balanced foundation of steadily amplifying but composed sound. When she sings to her lover, ‘Don't leave without me’, Doumbia calls for a coherent sense of place, for a shared life with her partner in civil (lived) space. Yet, the reality of an imminent departure lingers, to which Doumbia adds, ‘Don't bring shame upon me’. The correlation of travel abroad – what Mande people call ‘tunga’, a sort of ‘journey into the unknown’ – and shame (malo) is significant; it epitomises the psychosocial risk of choosing to venture (locally or globally) into wild space. A Mande reading of Lefebvre's notion of perceived space will help elucidate the risks and realities of confronting wildness in modern society.

The dialectics of spatial practice

As the third part of the Lefebvrian model, perceived space joins conceived and lived space ‘in a dialectical interaction’, encompassing the subjective production, appropriation and deciphering of social space (Lefebvre Reference Lefebvre1991, p. 38). Rendered as ‘spatial practices’, perceived space constitutes an embodied, inter-sensual and interpretive engagement with conceived and lived space. It represents the visible, tactile, olfactory and aural dimensions of social space in which the body engages with, comprehends, and sometimes changes its social and material, lived and conceived surroundings.Footnote 12 In the Mande spatial paradigm, the concept of subjective agency, or ‘waleya’, closely approximates the spatial practices of Lefebvre's perceived space and personifies the spatial dialectics I am describing. In Mande social thought, waleya articulates at the socio-spatial interstices, or borderlands (dankun) of civility and wildness. From this space of the in-between, subjective action, or ‘kewale’, may have socially integrative or dissociative effects on society and therefore possesses a strong ethical inflection.

In Lefebvre's tripartite model, the notion of perceived space is the least developed and therefore the most ambiguous. Given this, I will emphasise here the richer (and perhaps more coherent) vision of socio-spatial dialectics offered by Mande social thought. My reference above to the ‘ethics’ of waleya (subjective agency) derives from the concept of ‘fadenya’. Translated as ‘father-child-ness’, fadenya refers explicitly to rivalry between children of different mothers in polygamous families and implicitly to an individual's desire to develop and refine the traditions of his or her ancestors, expressed by the notion of fasiya, or ‘cultural patrimony’ (literally, ‘father's lineage’; the ‘paternal’ corollary to the ‘maternal’ mores of badenya). In contrast to the relatively static space of social intimacy and morality (badenya) described above, fadenya is the conceptual vehicle of dynamism in Mande society. Where badenya works centripetally, bringing individuals bound by a common heritage (fasiya) together in civil space, fadenya acts centrifugally, spreading subjective agency (waleya) into the potentially threatening realm of wild space (see Bird and Kendall Reference Bird, Kendall, Karp and Bird1980). In ethical terms, fadenya is understood to engender both ‘negative’ (shameful and regressive) and ‘positive’ (salutary and progressive) effects; it represents a kind of ethical impulse for the dissociative and socially integrative acts associated with the term waleya (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Mande spatial practices.

Crucially, acts of socio-cultural innovation do not imply an emphasis of individualism over collectivity. In Mande social thought, innovation, or ‘positive fadenya’, is predicated on commitment to society's traditions (fasiya) and social mores (badenya) and describes how such traditions and mores are reproduced, or reinvented (cf. Hobsbawm and Ranger Reference Hobsbawm and Ranger1983) to meet the demands of, and even develop and improve modern social life.Footnote 13 This is the active expression of civility in Mande society, in contrast to the more passive, habitual, and morally grounded social practices of badenya. In cases where subjective agency does tend toward a more radical individualism, or ‘negative fadenya’, the cycle of departure (whether physical or ideational), innovation, and re-integration is broken and a dissociative breakdown into wildness (anomie, alienation, and sometimes violence) is manifest. This is what Doumbia warns against when she sings ‘Don't bring shame to me’ in the song ‘M'bifé’. Engendered by unethical behaviour, shame (malo) is the most prevalent expression of moral breakdown in Mande social life. At this point, rather than returning to the social comforts of civil space (the kind of celebratory rendering of African social life one has come to expect from Bagayoko and Doumbia's music), Dimanche à Bamako confronts the realities of socio-spatial wildness head on. The song, ‘M'bifé (Balafon)’ musically introduces this critical move.

Sounding the itinerant subject

‘M'bifé (Balafon)’ flows directly from ‘M'bifé’, with a key change up from A-minor to B-minor, cued by the lively strumming of an electric guitar (Bagoyoko's). Rapid and abrupt picking between the tonic and a minor third on the high E-string of an acoustic guitar (Chao's) provides a sense of acceleration from the previous track, moving the time signature from 4/4 to 4/8. The tempo is itself marked by a wispy, brushed (and probably programmed) cymbal hit (first heard in the final seconds of ‘M'bifé) struck on the offbeats of a pulse created by the bass guitar. This percussive counter-rhythm represents a significant musical motif that returns throughout Dimanche à Bamako. The sound of the cymbal hit has a mechanical quality to it, resembling the firing pistons of a car engine or the steam locomotion of a train. It signifies rapid movement on the road or the rails, and on songs like ‘Aristiya’, ‘Camions Sauvages’, and ‘Beaux Dimanches’ it is used to represent travel to and from home. The instrumental ‘M'bifé (Balafon)’ introduces this motif without lyrical reference – to concert tours (‘Artistiya’), freight transport (‘Camions Sauvages’), or ceremonial gatherings (‘Beaux Dimanches’) – and, lacking a clear sense of destination, becomes the musical embodiment of a more generalised sense of displacement and itinerancy.

The listener does, however, have a clear idea of the origins and direction of the movement ‘M'bifé (Balafon)’ represents: it is away from the civil space of sociality and intimacy expressed on the previous track, ‘M'bifé’; it is a move away from home. Juxtapose, for example, the young boy's personal greeting at the outset of ‘M'bifé’ with the verbal postcard he narrates for Chao at the beginning of ‘M'bifé (Balafon)’, inviting the world music maverick to the midland Malian city of Mopti (where some of the music and soundscapes were recorded for the album) for local fish and a chance to hear him play the ‘tam-tam’ (a hand drum). Social proximity and dialogue in the former give way to long-distance correspondence in the latter. ‘Chao, bisous!’ (‘Chao, kisses!’),Footnote 14 Mamadou says, concluding his invitation with hopeful affection. There is also the distinctive sound of the ‘balafon’, or ‘bala’, a kind of xylophone for which the song is parenthetically named. The multi-octave pentatonic melodies suggest that the instrument is a ‘balaba’ (‘large bala’), performed by peripatetic hunters and bards among Senufo and Bamana peoples of southern and central Mali. In fact, the sounds are programmed into a synthesizer performed by Cheick Tidiane Seck, himself a well-travelled world music veteran and a Malian native based in Paris since the mid-1980s. Taken as a whole, the aural referents on ‘M'bifé (Balafon)’ present a modern musical portrait of an age-old human condition: itinerancy.

This is a condition that Chao, the song's principal composer, is quite familiar with. ‘My things are in Barcelona’, Chao says, ‘but I'm not there very often’ (Falling 2007). Born to a Basque mother and a Galician father, Chao was raised in Paris where his family settled after fleeing fascist Spain under Franco. Growing up among immigrant communities in the Parisian suburbs was formative, and Chao made an early connection to the anti-racist, anti-fascist sentiments of the local French punk scene. Listening to the innovative punk rock of UK bands like Dr. Feelgood and the Clash (the late Joe Strummer was a good friend and role model), as well as the reggae of Bob Marley and the popular music of Latin America, further expanded Chao's musical horizons (Culshaw Reference Culshaw2007). After a brief stint with the group Hot Pants in the early-1980s, Chao formed the influential French punk/worldbeat band Mano Negra in 1987 (see Rivas Gamboa 2003). Eager to cultivate a personal, political and artistic connection to South America, Chao took his band (along with a circus and theatre troupe) on a boat tour of port cities on the Atlantic and Pacific sides of the continent in 1992, performing on a stage fashioned from the ship's cargo hold. The following year, Mano Negra travelled to Colombia, where they rode an old freight train to small towns and villages and performed for local populations (including peasants, paramilitaries, and drug traffickers). These adventurous and openly anti-establishment tours would have a lasting impact on Chao's socio-political and musical worldview. ‘In South America’, he says, ‘you can go to a lot of countries, and of course they're different countries, but the real border, for me, is between city and country’ (Falling 2007).Footnote 15

It is the condition and experience of the rural-to-urban and transnational migrant – the outcast, the refugee, the adventurer, the impoverished risk-taker – and the global political economy that surrounds him that becomes the principal focus of Chao's music and social activism. This is perhaps best exemplified by Chao's first solo album, entitled Clandestino (2000),Footnote 16 a reference to the informal and ‘hidden’ status of those who travel ‘without papers’. On the album's title track, Chao sings, ‘Solo voy con mi pena / Solaba mi condena / Correr es mi destino / por no llevar papel’ (‘I go alone with my burden / My fate stands alone / I'm destined to keep running / because I don't have papers’). Chao brought this message to the fore at a June 2007 performance at the Prospect Park Bandshell in Brooklyn (one of his rare appearances in the United States), where a banner draped across the stage read, ‘Immigrants are not criminals’ (Culshaw Reference Culshaw2007) – a sentiment that went over well with the principally Latin American crowd. As I will show, the theme of local and global migration and their psychosocial effects remains central to Chao's contribution to Dimanche à Bamako. As Richard Gehr of New York's Village Voice writes, ‘The record ends up a nearly perfect balance of [Bagayoko and Doumbia's] Bambara heritage and Chao's nervous deterritorialization’ (Gehr Reference Gehr2005). The song ‘M'bifé (Balafon)’, preceded by the familial ‘M'bifé’, musically introduces this ‘nervous deterritorialisation’, representing a kind of undifferentiated fadenya, an open-ended ethics that articulates both the possibility and the danger of venturing into the wild.

Moving now to the core of my analysis, I will consider two pairs of songs on Dimanche à Bamako: ‘Taxi Bamako’ and ‘Camions Sauvages’, and ‘La Réalité’ and ‘Sénégal Fast-Food’. In the first pair, I examine how Lefebvrian notions of lived and conceived space articulate as civil and wild space in the context of contemporary Mande society. I suggest that the phenomenal movement between spaces of civility and wildness, figured as the city (dugu) and wilderness (kungo), respectively, frames the spatial practices that define expressions of subjectivity in Mande society. With the second pair of songs, I examine how Bagayoko, Doumbia and Chao map this local disjuncture between civil and wild space onto the global context of the African diaspora as it is conceived and lived through the political economy of global modernity. Here, the ‘heart of darkness’ metaphor is reversed as ideas and experiences of ‘the West’ take on a savage and menacing character while ‘African’ spaces – at home or abroad – embody the sense and sociability of everyday life in Africa.Footnote 17

Civil taxis and wild trucks

As a pair, the songs ‘Taxi Bamako’ and ‘Camions Sauvages’ communicate a social disjuncture between control and disorder, cohesion and dislocation, civility and wildness in contemporary Mali. In Lefebvrian terms, we may interpret this disjuncture in relation to the dialectic of lived and conceived space: While lived spaces index the civility of locally cultivated social relations, conceived spaces tend toward the abstract (political despotism, cultural homogenisation, social dislocation and alienation, etc.) and become wild. I will first consider the songs separately to show how they elucidate the local tensions of global modernity through their depictions of civil and wild space in Africa today. Then, by considering the two songs together, I will critically examine the expressions of modern subjectivity they convey. How do these songs describe the equilibrium between civil and wild space? What effects do maintaining or losing spatial balance in Mande society have on persons portrayed in these songs? I begin with the space of urban civility presented in ‘Taxi Bamako’.

This song exudes a dreamlike calm. Chao strums an electric guitar over programmed cymbal hits, creating a relaxed swinging rhythm that slowly travels between the tonic and the subdominant. Riding underneath this musical structure are field recordings of a Bamako taxi ride. By acoustically foregrounding city conversations and cacophonies to frame musical grooves, ‘Taxi Bamako’ brings the listener into the lived urban space it seeks to represent: the taxicab. These recordings are punctuated by overlaid samples of voices in French saying, ‘Bon, on y va !’ (‘Alright, let's go!’), and ‘Tu veux un taxi ici?’ (‘[Do] you want a taxi here?’). In front of the mix are Chao's lyrics voiced as intoned recitation in which he mimics the speech of a local taxi driver:

Taxi Bamako, où tu veux je t'amène. Taxi Bamako, tu m'appelles, je suis là. Je suis la plus rapide. Tu es ma seule cliente. Je fais ma course au ciel. Où tu veux, je t'amène. Tu t'assoies, je conduis. Taxi Bamako …

(Taxi Bamako, I'll take you wherever you need to go. Taxi Bamako, if you call me, I'll be there. Taxi Bamako, I am the fastest. Taxi Bamako, you are my only customer. I make my rounds in heaven. I'll take you wherever you need to go. You sit, I'll drive. Taxi Bamako …)

Musically, acoustically, and lyrically, Taxi Bamako paints an auditory picture of social harmony: whistles regulate traffic; the car engine purrs; the song's swing continues unperturbed; the dull din of the city hovers outside; and, Chao's driver assures his passenger that there won't be any troubles. ‘I make my rounds in heaven’, he says. The taxi and the city it navigates are made civil through material control and sociability. The taxi driver's livelihood rests on him seeking out clients and keeping his car running. He must manoeuvre through an uncertain urban economy, over pothole-ridden roads, and to the next city market that just might have that spare part he needs. ‘J’évite tous les trafiques, les problèmes mécaniques' (‘I avoid all traffic[king] and mechanical problems’),Footnote 18 the driver proclaims, providing a steady monologue for his anonymous passenger through the city. ‘I make my rounds in heaven’, he says. ‘You sit, I'll drive’.

Everyday sociability is central to the maintenance of civility in Mande society. In Bamako, taking a taxi isn't just about getting from point A to point B, it's also about establishing a social relationship between passenger and driver, if only for a brief ride into town. ‘It's an act of solidarity’, a Malian friend of mine who lives in Harlem explained. ‘It's not like taking a cab in New York. You can't just open the door, tell the driver where to go, and stare out the window. In Mali, you have to exchange greetings. You have to talk. It's an expression of humanity’.Footnote 19 It is the ‘humanity’ and ‘acts of solidarity’ that constitute the social space of the taxi that makes it a salient example of civil space in contemporary Bamako. In civil space, material wildness must be subdued, controlled and cultivated through human agency defined by custom, a sense of responsibility, and prescribed moral standards (badenya, fasiya); this is as true for a cornfield as it is for a taxicab. The maintenance of material civility is always social. When material civility is neglected – when fields lie fallow and cars break down – wildness settles in. This is the wild space depicted in ‘Camions Sauvages’.

The song opens with the sound of a truck barrelling past a rural landscape. Unlike the sociable urban soundscapes of ‘Taxi Bamako’, those of ‘Camions Sauvages’ confront the listener with the menace of the Malian highway. As the rumble of the road falls back in the mix, an undulating harmonica pattern emerges, setting the beat. An acoustic guitar playing a G minor triad on the offbeat of an electronic drum sequence finishes the rapid, pulsating rhythm, resembling the hammering of an engine – an echo of the percussive ‘travel’ motif introduced in ‘M'bifé (Balafon)’. Mariam Doumbia's voice comes in as cadenced monotone speech, relating the ills of the wild truck in Bamana: ‘A bè sama faga. A bè Mali faga A bè girafew bèè faga. A bè syè faga. A bè Mali faga. A bè animaux bèè faga. Mobilikolo, ne t'a fè’ (‘It kills elephants. It kills Mali. It kills all the giraffes. It kills chickens. It kills Mali. It kills all the animals. Wild car, I don't like it’). In this litany of animals killed by the wild car, the word ‘Mali’ is mentioned twice. Significantly, Mali can mean ‘hippopotamus’, the contemporary ‘Republic of Mali’, or the thirteenth- century Mali Empire. Through repetition, the word ‘Mali’ evokes this range of meaning.

Through rhythm, speech and sound, ‘Camions Sauvages’ describes a destructive material force that is relentless in its menace to nature and society. ‘It kills Mali’, Doumbia says. The truck, making long trips between towns and cities, is caught in the depths of wild space. In Mande society, traversing the wilderness (kungo) requires integrity, skill and strength. Hunters, with their ethic of solidarity and specialised knowledge of the natural world, are considered best equipped for the journey between civil and wild space (Cashion Reference Cashion1984). For the Mande hunter, wilderness must be confronted socially. Initiates in a hunter's society learn the secrets of wild space in order to subdue, control and possess the vital forces (referred to in Mande languages as nyama) the wilderness contains. To hunt wildlife requires a shared understanding of the natural order that sustains it. Hunting is systematic, never random; its labour and its fruits are always shared. This is the progressive, salutary and re-integrative essence of ‘positive’ fadenya. By contrast, the wild truck represented on Dimanche à Bamako kills indiscriminately and alone; its brutish materiality barrels out of control through the countryside, threatening game, livestock, children, and Malian society itself. It is the embodiment of ‘negative’ fadenya.

Chao's recitation enters with a reverb-rich electric guitar marking the metre. Chao's French words add a subjective element to the truck's material wildness by introducing the dazed and fearful voice of the truck driver. He speaks, ‘la route est longue, mes pieds sont lourds, et mes paupières, lourdes comme du plombe, s’écrasent sur la route’ (‘the journey is long, my feet are tired, and my eyelids, heavy as lead, crash against the road’), between chants, ‘le longue des longues camions sauvages, le monde est mon camion sauvage’ (‘all along the long wild trucks, the world is my wild truck’). Solitude in the wilderness is dangerous. Mariam Doumbia calls out in song to the lone traveller in Bamana: ‘Mobilikolotigi, i tè fèrènè?’ (‘Driver of this wild car, can't you brake a little?’) But, her call goes unanswered. The driver rides along recklessly through the wilderness, motivated, Chao reminds us, by other wild forces. ‘C'est la panique économique’ (‘It's an economic crisis’), he sings, ‘la panique en Afrique’ (‘a crisis in Africa’). African truckers are driven by an economy that demands speed and efficiency despite poor infrastructure, irregular earnings, and questionable cargo. ‘It's a crisis’, sings Chao, ‘trop de traffiques’ (too much traffic[king]) (see Endnote 18). The driver must race down crumbling highways in the middle of the night to make one last delivery to earn the extra income he needs to make ends meet. ‘The world is my wild truck’, he laments.

The song ends with the voice of a young boy (the same Mamadou from the opening ‘M'bifé’ tracks) listing off stimulants used by truckers to navigate social and economic wildernesses: kola nuts, cigarettes and candy. Succumbing to material disorder and solitude in the face of economic pressure, the truck driver must keep his heavy eyelids open and keep going, no matter what or who gets in the way. ‘It kills Mali’, Doumbia says. The wild truck not only strips its occupant of humanity but also threatens the lives of those who encounter it, whether by force of impact or by the forces of global capital it serves. ‘It's an economic crisis’, Chao sings, ‘a crisis in Africa’. This is the crisis of global modernity engendered by subjective agency untethered from the moral and ethical norms of society (see Mbembe and Roitman Reference Mbembe and Roitman1995). ‘Too much traffic(king)’, says Chao. By putting the ideas of civil and wild space expressed in ‘Taxi Bamako’ and ‘Camions Sauvages’ together, I will now consider the effects of this socio-economic condition on modern subjectivity in Mali today.

In Mande society, the individual is caught between centripetal forces of community and centrifugal forces of competition, pulling and pushing between civil and wild spaces, in and out of social balance. This is the subjective locus of personhood, or ‘mògòya’ (literally ‘person-ness’), in the Mande world. As described above, the Mande kinship terms of badenya and fadenya elucidate these recursive spatial practices (see Figure 3). While badenya conveys a sense of community and a commitment to material and social order in the civil spaces of Mande society, fadenya articulates an individual's desire to compete with and transcend the traditions and mores of his or her ancestors by choosing to venture into wild space, whether material (the outlying ‘foreign country’ or ‘bush’) or conceptual (an innovatory or polemical ‘idea’). In Africa today, this wildness is increasingly defined by social discord manifest in political corruption, rampant globalisation, extreme poverty, and urban underdevelopment (see Ferguson Reference Ferguson2006), social realities that underlie the desire among many Malians to seek their fortunes abroad, on the road, in wild spaces.

Mande personhood (mògòya), or the achieved status and identity of the socialised individual in Mande society, lies in the dialectic of morality and ethics (badenya/fadenya), social affection and antagonism, commitment and critique, intimacy and innovation that motivates and defines subjective agency (waleya) in civil and wild space. These subjective polarities are never mutually exclusive; it is always a question of balance, of seeking equilibrium between interiority and exteriority, self and other, sameness and difference,Footnote 20 like the hunter who enters the wilderness to confront its dangers and returns to civilisation with a greater appreciation of the wilds' proximate alterity. In ‘Taxi Bamako’, the wildness of the car is controlled and understood through sustained human agency and practised knowledge, allowing for the civil use of the automobile in an otherwise uncertain urban economy. ‘I make my rounds in heaven’, the driver says, acknowledging a hopeful, but tenuous balance between the potential of material wildness and the maintenance of social civility in modern-day Bamako.

Yet, global modernity presents new challenges to social stability in Mande society. ‘It's an economic crisis’, Chao sings, ‘a crisis in Africa’. The continued subjugation of African governance to the political and financial interests of global capital in the West wreaks havoc on the saliency of local social order and makes the ‘post’ of ‘postcolonial’ seem absurd (cf. Cooper Reference Cooper2005). As political sovereignty is usurped and local economies destabilised, men and women must look for ways to support their families and preserve what little civility remains in their society. In post-, or neo-colonial Mali, this has led to an exacerbation of ‘negative’ fadenya, or social dislocation, divorced from the grounded, re-integrative force of social cohesion, badenya. Trapped by a vicious global political economy, contemporary African societies appear torn by clientelism, corruption and conceit, engendering a politics of exclusion that forces many into the wild spaces of poverty, migration, and backbreaking solitary labour. In this space of wildness, a sense of ethics and morality lose their meaning. Life becomes self-indulgent and destructive. ‘All along the wild trucks’, the driver says, ‘the world is my wild truck’.

The rest in the West

Civil and wild spaces are transposed from the local to the global in the songs ‘La Réalité’ and ‘Sénégal Fast Food’. These songs describe the condition of the African migrant, potential and actual, who ventures out into the wilderness of ‘global cities’ in the Global North (Sassen Reference Sassen1991) to make a living, support family and friends back home, and secure personal prestige through hard work. However, while cities like Paris, London and New York present the (often tantalising) potential for wealth and prosperity, they also contain real social, political, economic and environmental dangers to the (often undocumented and ill-prepared) African migrant. In the wild West, one may encounter racism and social alienation, threats of deportation and human rights abuse, strenuous labour and paltry profits, sub-standard housing and brutal winters, and so forth.

To confront these harsh realities requires knowledge, courage and solidarity. As Paul Stoller observed in his fieldwork among African traders in New York City, shrewd migrants learn to exploit the concentration of wealth, goods and services in the West by creating informal socio-economic networks on the formal margins of urban economies (Stoller Reference Stoller2002, pp. 91–3, 106). Yet, even with such collective tactics, the subjective burdens of migration remain significant. ‘Immigration … usually reinforces social isolation’, writes Stoller. Isolation, in turn, inhibits participation in the daily ‘activities and interactions’ that make an individual's social life meaningful and productive (ibid., p. 159). It is precisely this tension between solidarity and solitude, prosperity and privation, work and unemployment, hope and despair that ‘La Réalité’ and ‘Sénégal Fast Food’ communicate; they represent the psychosocial tensions of global modernity as conceived and lived abroad in the African diaspora.

‘Dans ce monde’ (‘In this world’), sing Amadou and Mariam, ‘triste réalité’ (‘[it's the] sad reality’). It's a reality of discontinuity and injustice. Amadou laments: ‘il faut que d'autres naissent, d'autres meurent’ (‘some must be born, [while] others die), ‘pendant que d'autres crient, d'autres rient’ (‘while some scream, others laugh’), ‘pendant que d'autres travaillent, d'autres chaument’ (‘while some have work, others are jobless’), ‘il faut que d'autres veillent, d'autres dorment’ (‘some must stay awake, [while] others sleep’) ‘pendant que d'autres chantent, d'autres pleurent’ (while some sing, others cry’). ‘In this world’, they sing, ‘[it's the] sad reality’. This lyrical lament is playfully counterbalanced with a steady house beat, blues-driven guitar riffs, disco bass lines, and tender vocal melodies, giving the song a decidedly upbeat groove. As Ian Anderson writes in fRoots magazine, ‘La Réalité piledrives like a classic R & B revue, all wailing sirens and muscular blues guitar’ (Anderson Reference Anderson2005). Though, while the music ‘jumps at you’ with ‘a festive, celebratory vibe’ (Poet Reference Poet2005), the lyrics betray an anxious melancholy cast in plain realism. As Damon Krukowski of The Boston Phœnix writes, ‘The lyrics bewail the sadness of life while urging us to dance’ (Krukowski Reference Krukowski2005). This makes ‘La Réalité’ an example of Chao's own oxymoronic ‘Merry Blues’ (2002). ‘In this world’, Amadou and Mariam sing, ‘[it's the] sad reality’.

The music video for ‘La Réalité’ (Bagayoko and Doumbia Reference Bagayoko and Doumbia2005) is set in a Parisian hair salon and convenience store, two canonical sites of immigrant labour and sociability in the West African diaspora (see Skinner Reference Skinner2005, Chapter Four). In these social spaces hair is braided, merchandise is hawked, and conversations unfold underneath the music's even groove. A young man in a denim jacket hovers outside the storefront of ‘Coiffure Afro’, wringing his hands. He tries to grab the attention of passers-by, though his precise intentions are unclear. Is he looking for someone in particular? Is he trying to attract customers? Is he proffering a good or service? Is he trying to hustle someone? Is he begging for money? Inside the salon, the space is convivial. Clients and their families lounge and chat as the workday proceeds. Friends at the convenience store admire athletic shoes, videos and CDs while sharing a friendly laugh. These scenes periodically cut to an intimate concert venue where Bagayoko and Doumbia perform for (what appears to be) an all-African audience. Manu Chao (who contributes backing vocals, instrumental accompaniment, and musical programming to the song) stands inconspicuously in the background, singing and strumming his guitar beside a jembe (hand drum) player (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Amadou and Mariam with Manu Chao (Malick Sidibe).

While a typical cosmopolitan ‘world beat’ narrative would argue that the European production and Parisian setting of this song patinas over its exotic African-ness, rendering it more accessible to a global (Western) audience, the song's music, lyrics and images tell a different story. In ‘La Réalité’, the West is wild; it exemplifies what Lefebvre would describe as conceived space permeated by the abstract, the authoritarian and alienating. As the beat kicks in, a police siren sounds, indexing the uncertain civil status and racial profiling that leaves many immigrants (along with ethnic and religious minorities) in Europe and America susceptible to excessive state surveillance, discipline and violence; it is an aural sign of wildness. The reality of such abuses has been made abundantly clear through the recent outbreak of civil unrest among North and West African communities in France's urban ghettos, as well as in the string of protests organised by Mexican labour migrants in the United States (events which are critically related in the lives and works of Bagayoko, Doumbia and Chao). In the midst of this repressive reality, immigrants struggle ‘to get by’ – what francophone Africans mean when they say, ‘je me débrouille’ (cf. Bayart et al. Reference Bayart1999, pp. 38–9). In order to get by, personal needs and expenses must be sacrificed to meet the expectations of financial support from friends and family back home. In the video, a young man in a denim jack hovers outside the salon, trying to grab the attention of passers-by, looking for an opportunity, or just a break. In the face of such social and economic burdens, it is all too easy to succumb to sentiments of gloom and alienation. ‘While some scream, others laugh’. ‘While some sing, others cry’. ‘In this world’, sing Amadou and Mariam, ‘[it's the] sad reality’.

In spite of the troubling social, political and economic realities encountered by the immigrant in the Western wild, African travellers still go to great lengths to pursue the possibility of prosperity that the West is believed to possess. The pursuit of this prospect is portrayed in the song ‘Sénégal Fast Food’. The music video for this song (Bagayoko and Doumbia Reference Bagayoko and Doumbia2005) tells the story of a young man who is preparing to leave for a journey to Paris. We follow him, through Chao's polyglot lyrics and the diverse social spaces of downtown Dakar, as he courts his fiancé, seeks counsel from elders, visits family and friends, wanders the city, and anxiously anticipates his departure for Europe. As the young man moves from place to place, person to person, the listener/viewer encounters signs of just how profoundly globalisation, as projected from the Global North, has been inscribed on cities in the Global South like Dakar: the young man has a rendezvous with his fiancé at the Manhattan Fast Food restaurant, they go to the movies at Cinéma Le Paris, and he watches and cheers as a Paradise Airlines flight takes off. ‘Quelle heure est-il au paradis?’ (‘What time is it in paradise?’), Chao asks wistfully.Footnote 21

The young man's urban itinerary exemplifies a tenuous civility in the face of an encroaching modern wilderness. He encounters the conceived and abstract spaces of the city – marked by signs of globalisation – through interpersonal contact with his peers, loved ones, and fellow urbanites. Yet, while social contact with conceived space has the potential to civilise urban wildness, concretising its abstraction, it may also engender personal disaffection and despondency. As the young man climbs onto the back of a public van, we discover that he's on his way to the French consulate to solicit a visa. His grandmother is in the hospital. Exigency layers upon anticipation. At the consulate, he joins dozens of others in line, all holding official documents, waiting expectantly for a chance to travel to and work in the West. They are preparing for what Mande speakers call ‘tunga’, or ‘an adventure abroad’, a journey into the wild to seek one's fortune, or just make a living. In the video, black ink fills the screen and the English word ‘denied’ appears. The young man is cast off, rejected, while others continue to wait, hoping to receive their ‘passport to paradise’. The young man's fiancé sits alone at the Manhattan Fast Food while he lingers at the waterfront, watching anonymous passengers embark on a ferry. He moves on to receive guidance from a local soothsayer. Later, he and his fiancé have their portrait taken. He visits family and begins his journey abroad, overland, without papers. The story ends in Paris and Dakar. In the French capital, the young man is arrested on the city streets. Back home, his girlfriend waits for a long overdue phone call. ‘What time is it in paradise?’ sings Chao.

‘Cinéma Le Dakar, Bamako, Rio di Janeiro’, Chao muses. ‘Où est le problème?’ (‘Where's the problem?’) ‘Où est la frontière?’ (‘Where's the border?’). The problems and borders are, of course, all too real. In ‘Sénégal Fast Food’, Chao's concern for the divide between the city and countryside is projected onto the postcolonial rift between the Global North and South. ‘Entre les murs’ (‘Between the walls’) he sings, ‘se faufilent dans l'ascenseur, ascenseur pour le ghetto’ (‘[people] shuffle forward in the elevator, elevator to the ghetto’). Subject to the structures and strictures of conceived space at home, eager adventurers edge by each other toward signs of progress and prosperity abroad. For those who make it, the reality of the modern-day metropole is much wilder than anticipated. As depicted in ‘Sénégal Fast Food’, the African's journey to the West is an ‘elevator to the ghetto’, a desperate move into wild space. How do people confront this condition? How is it managed? How is it lived? To get by in wild space requires knowledge, courage and, most importantly, solidarity. In particular, the formation and maintenance of diasporic community is essential to the psychosocial welfare of migrant peoples.Footnote 22 In ‘La Réalité’, this local space of global community is embodied in the conviviality of work and leisure at the Parisian hair-braiding salon and convenience store. In ‘Sénégal Fast Food’, we discover that the roots of diasporic community emerge from intimate social relations established at home in Africa. To confront ‘the sad reality’, to manage the socio-economic burdens of transnational migration, to live a meaningful life abroad, in the midst of the Western wilderness, one must pursue ‘positive’ fadenya, by cultivating community abroad with strong ties to home (see Skinner Reference Skinner2004, Reference Skinner2005, Reference Skinner, Falola, Afolabi and Adésànyà2008).

Celebrating civility in the modern world

At the outset of this article, I asserted that subjective movement (waleya) between civil and wild space produces dynamism and discord, creativity and conflict, innovation and intrigue in Mande society. I described such movement as articulations of ‘positive’ and ‘negative’ fadenya (‘father-child-ness’), an ethical dichotomy of spatial practice from which much of the meaning of Dimanche à Bamako derives. This ethical agency was, in turn, contrasted with the morality, stability and conviviality of tradition and social mores, which I termed as expressions of fasiya (‘cultural patrimony’) and badenya (‘mother-child-ness’), respectively. In my analysis of Dimanche à Bamako, I considered how local and diasporic encounters with global modernity have engendered an intensification of fadenya in Africa today, increasing subjective moves into wild space; this was exemplified by the song ‘M'bifé (Balafon)’. More and more, the ethics of these moves tends toward the ‘negative’ as the demands of fast capitalism and rampant globalisation threaten the saliency of local civility in African communities, at home and abroad; this was portrayed in the songs ‘Camions Sauvages’, ‘La Réalité’, and ‘Sénégal Fast Food’. ‘An bèè bè nin ko'in na’ (‘We are all in this situation’), sing Bagayoko and Doumbia in the chorus of the latter song, ‘si tè nin ko'in cogo dòn’ (‘[but] no one knows what its nature is’). This critical stance toward the political economy of global modernity and its effects on African social space distinguishes Dimanche à Bamako from Bagayoko and Doumbia's previous work and highlights the curatorial hand of Chao, whose political activism is his musical hallmark.

Yet, as the album cover shows (Figure 1), this is ultimately an ‘Amadou and Mariam’ record, and their celebratory and hopeful worldview strongly marks the affective and semantic character of Dimanche à Bamako. A critical theme throughout the album is the need to foster community and affirm personhood through the conscious cultivation of what may be called ‘a civil space of global modernity’. ‘Anw minw bè jamanajanw na’ (‘We who are in far-away countries’), continues the couple's chorus on ‘Sénégal Fast Food’, ‘kana nyinè an nyògòn ko de’ (‘don't forget our common cause’). This emphasis on the importance of civility in lived space (at home and abroad) comes forward in the intimacy and sociability expressed on ‘M'bifé’ and ‘Taxi Bamako’ discussed above, but, elsewhere, Bagayoko and Doumbia insist on a much stronger turn toward tradition (fasiya) and social mores (badenya) in the modern world. I conclude with an analysis of the songs ‘La fête aux Village’ and ‘Beaux Dimanches’, which together articulate a kind of synthesis of lived and conceived space, celebrating civility in an anxious time of wildness.

The two songs highlight the character and value of local tradition and mores in Mande society, expressed through the ceremony of community celebration (‘La Fête au Village’) and the ritual of marriage (‘Beaux Dimanches’). Introduced by Bagayoko's lilting electric guitar, ‘La Fête au Village’ hovers between two chords in D minor, punctuated by the voices and bustle of a neighbourhood soundscape. The absence of motorised noise in this aural space locates the song in the countryside, the social space of the ‘village’ to which the song title refers. This musical/acoustic setting gives a wistful intimacy to Bagayoko's somewhat strained song, in which he implores his beloved: ‘Fais toi plus belle / pour la fête au village’ (‘Make yourself beautiful / for the village party’). Doumbia replies, with longing compassion, ‘Je serai la plus belle / pour toi mon amour’ (‘I will be the most beautiful / for you my love’). Taking on the voice of a village ‘paysan’, or peasant, Bagayoko sings of the beans he has grown for the various families of Mande: Keita, Coulibaly, Traoré, Dembelé, Koné, Diarra, Touré and Samaké. The bean offering is a cultural reference to ‘sanankunya’, or ‘joking relationships’ in which public mention of another family's bean-eating habits inspires humorous exchange and provides a dialogic means to quell social conflict. Social harmony is further affirmed as Bagayoko describes those who will come from afar by motorbike, bicycle, boat, train and car ‘pour la fête au village’ (‘for the village party’) – a literal image of the centripetal and re-integrative social force that is badenya. Acoustically embedded in the natural soundscape of the countryside and musically framed by the subtle harmonies of guitar and voice, the song's lyrical references to cultural traditions and social mores, calling on displaced villagers to return to their native community for a collective fête, constitute the album's most poignant representation of an ideal-typical civil space.

‘Beaux Dimanches’ takes this idyllic notion of pastoral civility into the bustle of the big city: Bamako. Chao's concern for the tensions between city and countryside are here matched by Bagayoko and Doumbia's affirmation of rural-urban continuity. As the sound of a truck speeding down the road fades out, the sounds of children playing in a neighbourhood courtyard fade in. The pulsating onset of the mechanised cymbal hit, first heard on ‘M'bifé (Balafon)’, indicates that ‘Beaux Dimanches’ is about movement. Though, unlike Chao's earlier meditation on travel and wildness, ‘Beaux Dimanches’, composed by Bagayoko, is a story of homecomings, not departures. Men and women, neighbours and eager onlookers, praise singers and speechmakers, and the bride and groom are all gathered to celebrate. ‘Les Dimanches à Bamako’ (‘Sundays in Bamako’), sings Bagayoko, ‘c'est les jours de mariages’ (‘are the days for weddings’). Unlike the acoustically subdued sociability rendered in ‘La Fête au Village’, expressions of badenya in ‘Beaux Dimanches’ convey a frantic quality. The heavily picked guitar phrase musically articulates the bustle of urban space: ascending and descending, moving in and out of intervals, stopping and starting, buzzing and muting through a circular melody. Social life in the city moves at a quickened pace, but it is no less civil. Yet, as the percussive travel motif reminds us, social and material wildness are much closer in the civil spaces of the modern metropolis. Chao adds the sound of a mariachi trumpet to remind us of the global character of these contested urban spaces. Part of the local and global commotion in Bamako's ‘Beaux Dimanches’ is the work of resistance, of keeping wild space at bay and bringing people together to make way for celebration.

As a pair, ‘La Fête au Village’ and ‘Beaux Dimanches’ communicate the saliency and significance of ceremonial tradition (fasiya) and social mores (badenya) in the rural and urban, civil and lived spaces of contemporary Africa. Yet, performed from the vantage of the globetrotting Malian pop duo, ‘La Fête au Village’ and ‘Beaux Dimanches’ are not simply popular expressions of traditional praise for local civility. As Richard Gehr puts it, ‘Amadou waxes nostalgic for the country in ‘La Fête du [sic] Village’ and ‘Beaux Dimanches’, gorgeous songs revealing a subtle tension between the duo's regional upbringing and international yearnings' (Gehr Reference Gehr2005). Together, ‘La Fête au Village’ and ‘Beaux Dimanches’ articulate a local call to action in an era of global modernity: to preserve and sustain those ritual moments of conviviality and solidarity that remain the civil foundations of African communities, at home and abroad. Placed on either end of the album's most brutal portrayal of material wildness, ‘Camions Sauvages’, ‘La Fête au Village’ and ‘Beaux Dimanches’ express the need to civilise the wild spaces of globalisation. The songs are Bagayoko and Doumbia's own poetic act of ‘positive’ fadenya: to produce and cultivate a uniquely African civil space of global modernity through their own brand of world music.

Conclusion: a civil and wild wake-up call for world music

I began this article with a cursory observation of difference, juxtaposing Chao's poetics of political activism with Bagayoko and Doumbia's aesthetics of social solidarity: anxiety amidst encroaching wildness, on the one hand, celebration of enduring civility, on the other. In his article, ‘A sweet lullaby for world music’ (2000), Steven Feld uses the same vocabulary to describe responses to the phenomenon of ‘world music’ among artists, critics and academics. He contrasts ‘anxious narratives’ that question the authenticity and intentions of people who peddle in global sounds with ‘celebratory narratives’ that praise the potential of hybrid musics to promote cultural diversity and democracy (Feld Reference Feld2000, pp. 152–4). As a world music production in which global modernity – of which the world music industry is certainly a part (see Feld Reference Feld, Feld and Keil1994; Erlmann Reference Erlmann1996; Stokes Reference Stokes2004) – is represented through the ‘anxious’ expressions of wild space and the ‘celebratory’ expressions of civil space, Dimanche à Bamako is a salutary example of a collaborative musical recording that transcends this anxious/celebratory dichotomy (cf. Meintjes Reference Meintjes1990). It is an ‘Amadou and Mariam’ album produced ‘by and with Manu Chao’; a collaboration that bridges the Global divide between North and South by artfully weaving the civil and wild experiences of African communities, from Bamako to Paris (Figure 4). ‘C'est un album métissé’ (‘It's a hybrid, mixed album’), says Bagayoko, ‘with rock and roll, Africa and Europe’. ‘Ce sont des échanges permanents’ (‘These are permanent exchanges’), affirms Chao.Footnote 23 I believe my foregoing analysis of the album's socio-musical content gives empirical credence to the artists' professed syncretic and collaborative endeavour. Perhaps the world music industry would be less anxiety ridden were it to produce more albums like this one.