Does religiosity have a constraining impact on support for an ethnic insurgency? While most studies investigate to what extent religious fractionalization or denomination across societies plays a role in a conflict (Reynal-Querol Reference Reynal-Querol2002; Tusicisny Reference Tusicisny2004; Svensson Reference Svensson2007; Toft Reference Toft2007), this study asks if religiosity reduces support for insurgency among minorities. Huntington (Reference Huntington1996) and his supporters argue that sharing the same religion and adherence to the shared belief reduces the likelihood of the conflict. Others emphasize how religious people may prefer nonviolent methods over violent ones and refrain from supporting insurgent organization (Johansen Reference Johansen1997; Haynes Reference Haynes2009) or point to the soothing role of religion in a conflict environment. For example, Zic (Reference Zic2017) argues that factors associated with a civil war such as displacement, exposing to violence, death, and other related factors cause people to be more religious and support for the religious parties. Scholars such as Juergensmeyer (Reference Juergensmeyer1993) and Philpott (Reference Philpott2007), on the other hand, emphasize the rise of religious nationalist movements in recent decades, replacing secular movements, however, in contrast, others argue for the transformative role of ethnic identity on religious societies (Aspinall Reference Aspinall2009; Gurses Reference Gurses2018).

This study focuses on the relationship between religiosity and insurgent movements and argues that securitization of an ethnic identity leads to a multi-ethnic state to manage minority issues by prioritizing security policies over normal politics through inclusive and representative public policies (Buzan et al. Reference Buzan, Wæver and De Wilde1998, 285). This reproduces a cycle of assimilationist and discriminatory policies that put distance between ethnic minorities and majorities in terms of both groups' treatment by the state institutions and economic opportunities, resulting in the formers' social, political, and economic marginalization. This marginalization diminishes the positive effect of “all citizens equal before the law” and religious brotherhood discourses from the government and other state institutions against a rebel group among all but especially religious citizens, who instead internalize messages such as inter-ethnic equality as members of the same faith. As a result, religious minority members, facing two contrasting narratives and strategic actions of rebel organization and governments in utilizing religious discourse, may not differ from non-religious people in assessing rebel organizations. Furthermore, minorities with high religiosity, in reaction to the perceived discrepancy between the equality and brotherhood discourses of the majority governments and the long-standing marginalization of minority rights on the ground, are likely to become receptive to the messages of a rebel group that claims to fight for their cultural and political rights.

To test our hypotheses, we utilized two original nationally representative surveys in Turkey, where the ethnic civil war between formerly Marxist–Leninist organization, the Kurdistan Workers' Party—The Partîya Karkêren Kurdistan (PKK) and state security forces has resulted in tens of thousands of lives since its first attacks in 1984. The first study was conducted in November 2011 in a low-conflict period and the second one in April 2013, one month after a ceasefire between the government and the PKK. Using these nationally representative surveys with around 6,500 and 7,000 individuals respectively, we identified citizens of Turkey with Kurdish ethnicity and constituted our samples of 901 and 1,237 Kurds living across the country.Footnote 1

The findings suggest that religiosity does not hinder mass support for an ethnic insurgent organization, that is to say, the PKK. Those who are more pious (private religiosity) and those who support religion in the public sphere (public religiosity) do not differ from the rest. We also found that support for the insurgency is higher among religious Kurds that hold the perception of socioeconomic inter-ethnic inequality between Turks and Kurds. Other findings are also noteworthy. Grievances matter; political grievances (state discrimination); and economic one (inter-ethnic inequality) exert a significant impact on Kurd's support for the insurgency. While getting popular support from religious Kurds, the PKK is also popular among the left and Alevi Kurds. The cross-sectarian and religious appeal of the PKK among Kurds may suggest a greater disillusionment with the Turkish state as well as strong nationalism among Kurds.

This paper contributes to civil war, ethnic and religious literatures as well as Turkish and Kurdish studies. First, it reiterates that religion and religious identity are multi-dimensional and challenges a static view of religion expected to reduce support for a rebel organization. It shows that religious people may have secular political preferences and support a secular insurgency. It also presents the mechanisms through which strategic decisions of state and rebel movement in a lengthy civil war can positively affect public opinion toward the latter. Second, similar to the Free Aceh Movement case (GAM) in Indonesia, the discourse of Islamic brotherhood may not work in a more than three decades-civil war especially if Islamic governments reject inter-ethnic equality, favor the political and economic policies favoring a politically dominant group (see also Aspinall Reference Aspinall2009). Finally, it shows that political and economic grievances, with a higher impact with the latter, significantly affect one's support for the insurgency.

RELIGION AND SUPPORT FOR INSURGENCY

Focusing on civil wars, Walter (Reference Walter1997) shows that warring actors' identities along religious lines affect neither the likelihood of settlement nor the duration of post-settlement peace. Similarly, Svensson (Reference Svensson2007) finds that there is no significant relationship between civilizational differences—defined using religion as the primary characteristic of civilizations—and the duration of armed conflicts. Reynal-Querol (Reference Reynal-Querol2002) argues that the commonality in religion does not breed political violence. On the other hand, Leng and Regan (Reference Leng and Regan2003), Fox (Reference Fox2004), Tusicisny (Reference Tusicisny2004), Collier et al. (Reference Collier, Hoeffler and Söderbom2004), and Basedau and Koos (Reference Basedau and Koos2015) differ in their views on the relationship between religion and political violence from the no-relationship findings. Fox (Reference Fox2004) claims that differences in religious identities among members of a rebel group may distort communication and therefore serve as an obstacle to a peaceful settlement of conflicts. Basedau and Koos (Reference Basedau and Koos2015) and Basedau et al. (Reference Basedau, Pfeiffer and Vüllers2016) suggest that religious grievances and the way religious elites frame these grievances and these grievances' overlapping with other identities exert significant influence on the onset and duration of the conflict. Leng and Regan (Reference Leng and Regan2003) assert that religious identity is fixed, and thus associated disputes are more difficult to negotiate than ethnic and linguistic conflicts.

While testing the relationship between religion and political violence, studies mentioned above focus on religious fractionalization or differences in religious denominations rather than on religious commitment. In contrast to the studies that foresee societal tension and thus conflict among religiously diverse societies, one could argue that sharing the same religion may be expected to foster affinity across ethnic groups. As a result, one may assume that between adherents of the same faith, strong religious beliefs discourage support for political violence against the state holding the same religious identity. Hayes and McAllister (Reference Hayes and McAllister2005) show that church attendance reduces support for paramilitary violence in Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland. Zic (Reference Zic2017) finds that Bosnians who are displaced during the war become more religious and support for religious parties. Johansen (Reference Johansen1997) points to the positive role of religion in a conflict environment such as the British India where religious Pashtun actors worked actively to promote tolerance in a dehumanizing social and political context. Others such as Toft (Reference Toft2007) argued for the transformative effect of religion and religious discourses and claims that religious outbidding among various groups may turn a civil conflict into a religious war.

On the other hand, others are skeptical about a positive relationship between religious similarities and the conflict and contend that the effect of religion may be conditional upon other factors. For example, some highlight elites' abilities to frame religious grievances effectively (Basedau and Koos Reference Basedau and Koos2015; Basedau et al. Reference Basedau, Pfeiffer and Vüllers2016) while Sarıgil and Fazlıoglu (Reference Sarıgil and Fazlıoglu2013) and Gurses (Reference Gurses2015) concur that religion is no cure for civil war in their work on Kurdish conflict in Turkey. Furthermore, Gurses and Rost (Reference Gurses and Rost2017) show in their large-N study that co-religiosity does not reduce the duration of peace after an ethnic civil war and even increase the likelihood of the recurrence of the conflict.

These studies provide us valuable insights regarding how religion and religiosity play a role in a civil war. However, they tell us little about how the strategic actions of governments and rebel organizations affect the relationship between religion and support for rebel organizations, and most importantly how ethnic minorities react to it. The ongoing Kurdish conflict in Turkey may illustrate this relationship.

THE KURDISH CONFLICT AND SECURITIZATION OF KURDISH IDENTITY

The roots of the Kurdish conflict in Turkey goes back to the centralization policies of the Ottoman Empire in the mid-1800s when Ottoman administrators commenced abolishing the semi-autonomous status of the Kurdish region (Yadırgı Reference Yadırgı2017).Footnote 2 These policies included installing officials from Istanbul rather than employing local ones and removing the region's centuries-long tax-exempt status, which increased skepticism toward Istanbul among Kurdish leaders (Üngör Reference Üngör2012; Özok-Gündoğan Reference Özok-Gündoğan2014). The Ottomans developed a variety of strategies to control the Kurdish Emirs, some of whom unsuccessfully rebelled against the Ottomans. First major rebellion against the Ottoman Empire (and later Qajar Dynasty) was launched by a religious leader, Sheikh Ubeyduallah, who sought recognition and sovereignty from these two empires. Throughout the early 20th century, the centralization and subsequent Ottomanization/Turkification policies disrupted Kurdish political and economic landscape, resulted in the underdevelopment of Kurdish regions (Yadırgı Reference Yadırgı2017). During Turkey's War of Independence (1919–1922), Turkish military elites successfully enjoined Kurds to fight against foreign invaders, temporarily halting the most repressive policies until the new republic was declared (Üngör Reference Üngör2012).

The ruling elites of the new republic, mostly former generals or officials in the Ottoman Empire had shared the belief that implementing political reforms for (religious) minorities in the 19th century did not stop the disintegration of the Empire. Disturbed by this experience, despite their rhetoric and promises during the Independence War, the founding elites of the republic discounted any political reforms that granted cultural or political autonomy for Kurds. They instead formulated repressive policies that coerced assimilation and treated Kurdish ethnicity as an existential threat (Buzan et al. Reference Buzan, Wæver and De Wilde1998; Roe Reference Roe2004; Yeğen Reference Yeğen2009). To assimilate Kurdish population largely residing in the southeast of the country into new secular Turkish national identity, the state banned the Kurdish language in public spaces, including the street names and music, and Kurdish names of villages, towns, and mountains were replaced by Turkish names (Aslan Reference Aslan2007; Belge Reference Belge2016; Gurses Reference Gurses2018). Parents could not give Kurdish names to their newborn children, and in the eastern and southeastern region of Anatolia, Kurdish schools (mostly religious schools called medrese) were closed (Marcus Reference Marcus2007). Not surprisingly these and subsequent policies associated with direct rule, increased resentment; resulting in the second major Kurdish rebellion against Turkish state, again led by another religious leader, Sheikh Said, and some 18 others including the Ararat rebellion that took several years to completely suppress in the Kurdish dominant southeast Turkey (Yeğen Reference Yeğen2007; Belge Reference Belge2011).

Rebellions and armed struggles against the state were thoroughly repressed by the late 1930s and disappeared until the late 1970s. While the exile of traditional Kurdish elites and notables were also applied selectively in this era, cultural revivalism marked the post-1961 period during which the new Constitution expanded social and political liberties. In this new era, activists formed leftist cultural associations and organized “Eastern meetings” in the Kurdish-majority cities to problematize inequality between the East (Kurdish-majority cities) and the West and indirectly referring to the repressive policies of the state toward Kurds (Gündoğan Reference Gündoğan2011; Gunes Reference Gunes2013). However, the military guardianship over the regime did not stop restricting social and political freedoms in the name of state security. They instead banned the leftist organizations, especially Kurdish ones.

The repressive political atmosphere dominant in the 1970s, and the security policies emanating from the discourses of “the communist threat” by right-wing parties in governments led some Kurdish movements to believe that taking arm against this repressive state was the only option, while others remained committed to working inside the system to transform it. Beginning in 1978, martial law was declared in several Kurdish provinces, and in that same year, Turkey's rejectionist and assimilationist policies sparked the formal establishment of the PKK, a Marxist/Leninist group of Kurdish students active in the leftist and Kurdish student movements, headed by Abdullah Öcalan (Marcus Reference Marcus2007; Jongerden and Akkaya Reference Jongerden, Akkaya, Casier and Jongerden2011). Although the PKK engaged in armed struggles against Turkish security forces and pro-state Kurdish landlords, it had remained a marginal group and initially had relatively little popular support from Kurds in the region. However, Kurds' resentment of the state intensified following the military coup of 1980 as a result of the increased repression of the Kurdish language and culture, and the train of human rights abuses directed at Kurds in general and especially against Kurdish political elites in the Diyarbakir Prison (Aydin Reference Aydin2018). The PKK's first major deadly attack came only months after the military transferred power to civilians on August 15, 1984, and Kurds, especially those in southeastern Turkey, saw the strikes against the security forces as a legitimate response to the state's repressive and assimilationist attitudes toward Kurds (Bozarslan Reference Bozarslan2001).

The official denial of Kurds finally ended in 1991 when the government lifted the ban on speaking ‘languages other than Turkish’ although it did not explicitly mention Kurdish. While the state gave up the denial policies and recognized, at least informally, Kurds as a distinctive ethnic group, it has, until the early viewed Kurdish demands for rights such as the recognition of their status a separate ethnic group with a distinct language, and for including that language in school curricula, as examples of separatism and support for the PKK.

The AKP era initially seemed to deserve the benefit of the doubt from Kurds as its political discourse and reforms appeared to start the de-securitization of Kurdish identity. The state of emergency laws had governed the Kurdish majority cities in most of the history of Turkish republic as well as since 1987. The AKP abolished it, during which had facilitated the extrajudicial killings of many Kurdish political elites and ordinary citizens as well as human right abuses and civil and political restrictions. Besides, the AKP leader Erdogan saw secularism as a cause of division between Turks and Kurds and “highlighted the value of unification and brotherhood based on ‘common citizenship’ in the Republic of Turkey” (Yavuz and Özcan Reference Yavuz and Özcan2006; Somer and Glüpker-Kesebir Reference Somer and Glüpker-Kesebir2016, 8). To the chagrin of the Kemalist establishment in the state apparatus, the AKP governments have passed several reform bills in the parliament such as restoring Kurdish names to villages, Kurdish language as an optional course and broadcasting Kurdish in public and private channels. While their implementation was delayed or stagnated by unwilling security and bureaucratic state apparatus, these reforms brought hopes and optimism among those who seek peaceful solutions to the conflict (Weiss Reference Weiss2016, 577).

While the AKP has taken such positive steps toward the Kurdish conflict, it almost simultaneously imprisoned more than 8,000 members of the Kurdish political movement, delayed reforms, and did not act on the recognition of Kurdish identity in the constitution and of collective cultural and political rights such as education in the mother tongue. Moreover, the periodic hawkish discourse of Erdogan on the Kurdish conflict questioned whether Erdogan is genuinely interested in peaceful solutions or not. The AKP's condescending discourse and arrogance toward the Kurdistan Regional Government in Iraq and its aggressiveness toward the creation of a de facto Kurdish autonomy in Syria made many believe that the AKP is no longer a reformist party, but became a party of the state, embracing the state discourse toward the Kurdish conflict, bestowing some cultural rights as individual rights and denying any collective rights for Kurdish minority.

This period also witnessed the growing authoritarianism in the country, especially since 2011. Regression in civil and political liberties, the Gezi Park demonstrations, and the end of the political alliance between the Gulenist movement and the AKP government most openly since the December 17–25 corruption probe in 2013 have resulted in the further political repression along with ideological and ethnic polarization of Turkish society (Karakoç Reference Karakoç2018, 196–198). The AKP governments dismissed the rule of law, increased the number of political prisoners and condoned human right abuses, which led Esen and Gumuscu (Reference Esen and Gumuscu2016) to put Turkey into a category of competitive authoritarian regime, especially since 2015. The securitization of Kurdish identity and repressive policies associated with it have more harshly been re-employed soon after the significant loss of vote of the AKP and the victory of the HDP in the June 2015 election, which has also finalized the AKP's new status as a state party for the Kurdish insurgency and political movement, if not most Kurds.

ARGUMENT

Kurds and Turks share the same religion and most of these groups belong to the Sunni sect, while a minority of both groups identify themselves with Alevism, Shi'a, and other beliefs. Even the most secular Turkish governments in the post-1984 era have not been hesitant to utilize religious (Sunni) discourse to attempt to diminish support for the PKK. Especially during the AKP era, the religious schools (Imam Hatips) have mushroomed in the region as mosques since the 1990s, relative to the rest of the country (Gurses Reference Gurses2018). The instrumentalization of the Directorate of Religious Affairs (Diyanet) for domestic and foreign politics has been intensified under the AKP governments (Öztürk Reference Öztürk2016). Diyanet has been tasked with promoting (secular) Sunni (Hanafi) national identity, but its activities for promoting religiosity among Kurds in the Kurdish-dominated cities increased since the AKP came to power (Gurses Reference Gurses2018; Lord Reference Lord2018; Sarıgil Reference Sarıgil2018). Diyanet's salaried imams and the employment of “meles,” who are, the graduates of informal religious schools (madrasas) in the region, have been mobilized to discredit the PKK in the eyes of the public. These madrasas had played a crucial role in preserving non-politicized Kurdish Islam in the country, with some concession to the state (Yüksel Reference Yüksel2009). While some Sheiks and meles remained supportive of the Kurdish political movement, others passively or actively took side with the state, upholding the long-standing state's position that the PKK is an atheist organization that fights against Islam, through their sermons and daily interaction with Kurds in the region (Sarıgil and Fazlıoglu Reference Sarıgil and Fazlıoglu2013).Footnote 3

To counterattack the government's effort and increase its support among the population, the PKK “has given up its arrogant attitude toward Islam” (Van Bruinessen Reference Van Bruinessen1991, 24), right before formally leaving its Marxist/Leninist ideology in the early years of the post-Cold War period. This strategic move can also be found in the writings of Öcalan who had considered Islam as reactionary and backward in his writings in the 1980s, while later works assigned positive roles to Islam, in particular, the revolutionary character of Prophet against established order (Sarıgil Reference Sarıgil2018). In addition to the leftist reading of religion that emphasizes social and economic justice, the PKK has recruited some meles, formed several religious organizations such as the Democratic Islam Congress and others to compete with pro-government and other Kurdish Islamic movements over the support of traditionally religious Kurds (Çiçek Reference Çiçek2011). Being dismissive toward Friday prayer sermons in Turkish in state-controlled mosques, pro-PKK meles and other religious clergies initiated alternative Friday prayers where sermons were delivered in Kurdish in March 2011 (Sarıgil Reference Sarıgil2018). Furthermore, the pro-Kurdish BDP (Peace and Democracy Party) in the elections of 2011 successfully nominated several prominent political Islamists as MPs or mayors for some Kurdish-dominant cities in the region.

Despite the Kurdish parties' strategic moves to lure religious Kurds into its ranks and develop and propagate religion-friendly approach, one could argue that the group's Marxist background and sudden change of heart toward religion and the government's attempt to use religion as a common bond between Kurds and Turks may reduce support for the PKK among religious Kurds. First of all, political Islamists or religious figures exist neither among the leadership cadre of Kurdish parties nor of the PKK. Kurdish parties' or the PKK's coalitions, electoral or not, have always been with secular/socialist parties (Çiçek Reference Çiçek2013). Second, the PKK is known to be the most secular movement in the Middle East and many find that its position toward religion is tactical, not genuine (Jongerden Reference Jongerden and Gunter2016).

These observations and realities do not help the PKK or Kurdish nationalist movement to capture the full support of religious Kurds. However, there is no evidence that the Turkish state's policies on the use of religion to distance Kurds from the PKK do work as well. Kurds, especially in the southeast, have started to realize in the 1990s that state repression and extrajudicial killings are not only targeting those who support the PKK but also anybody who demands the recognition of Kurds and Kurdish language. Most conspicuously, the murder of a human right activist in 1991, Vedat Aydın and the indiscriminate shootings to the participants of his funeral by the security forces and killings of dozens in his funeral crystalized, especially for some Kurds with no affiliation with the PKK, that the PKK may be the right to fight against such oppressive state (Aydin Reference Aydin2018). Subsequent security oriented policies assisted the perception that Kurds are not equal citizen of the state and that they do not share neither the same rights nor opportunity in “Turkish” state.

Turkish governments and the military have used religious brotherhood discourse in the 1990s to eliminate support for the PKK. This discourse has been more visible during the AKP's rule in the post-2002; however, this discourse has not been materialized on the ground. The gap between the discourse and the AKP's policies on the Kurdish minority rights have augmented skepticism among Kurds, including religious ones that have usually voted for center-right or Islamic parties. Furthermore, the (Uludere) Roboski massacre on December 28, 2011, a few months after the first survey was conducted, increased disillusionment among Kurds. The AKP's indifference toward the killing of 34 Kurdish smugglers by the Turkish war jets as well as keeping the side with the military and its personnel on this massacre (no charges against those who order/fire) led some religious Kurds to associate the AKP with the repressive state and its apparatuses. Utilizing the Islamic discourse by the secular and then conservative Turkish governments in the 1990s and 2000s to suppress ethnic demands among the Kurdish population have not been effective any more in this repressive political context (Sarıgil and Fazlıoglu Reference Sarıgil and Fazlıoglu2013; Gurses Reference Gurses2015).

Toft (Reference Toft2007) argues that elites adopt religious outbidding to increase their credibility and survival in a conflict, which may result in a religious civil war. However, religious outbidding in the Kurdish conflict has not turned it into a religious civil war. The state policies to promote religiosity in the region as well as intense competition between Islamic and secular Kurdish movement to appeal to traditionally religious Kurds have gradually pushed secular and Islamic groups to adopt similar political discourse regarding the origins of the conflict and their demands from the government (Çiçek Reference Çiçek2013). For example, almost all Kurdish political organizations demanded the use of the Kurdish language in schools and mosques, Kurdish names for children, and Constitutional recognition of Kurds (Sarıgil and Fazlıoglu Reference Sarıgil and Fazlıoglu2013, 554–5). The leading figures of Kurdish Islamic organizations such as the Zahra Group hold the view that “…you regard the Kurds as your brothers, but on the other hand, you ignore their language and cultural rights… rather than Islamic brotherhood, equality would be the real solution to the problem” (Sarıgil and Fazlıoglu Reference Sarıgil and Fazlıoglu2013, 555). On the other hand, pro-PKK nationalist movements referred to Quranic verses calling for the importance of diversity and equality of all people with different nationalities before God as well as the right to fight against injustice and oppressors, as an Islamic duty. This leftist discourse has also retrospectively been widely used to define past religious rebellions such as Sheikh Said of 1925 who rebelled against the state while the leftist Kurdish movements in the 1960s and 1970s were previously either quiet on the nature of Sheikh Said Rebellion or defined it as a reactionary (feudal) rebellion.

Equally importantly, disappointed by the Turkish Islamic communities and their nationalistic discourse who pursued similar antagonistic positions with the state, such as associating the Kurdish conflict with terrorism, religious Kurds have increasingly realized that Turkish Islamic movements and the AKP use the brotherhood in Islam discourse as an instrument, not a conviction. Besides, for Kurds, the close bond between Turkish Islamic movements and the state in their discourse, especially on the Kurdish minority rights and conflict has crystallized Kurdish ethnic identity vis-avis religious identity. Ethnic identity, not shared religious identity, has been politicized. Many have remained as pious in this long-standing civil war; however, the conflict has secularized their political choices associated with ethnic identity over the years. As a result, like non-religious people, our expectation is that religious people may see the PKK as an organization that fights against the repressive Turkish state, defending the linguistic, cultural and political rights of Kurds even though they may not agree with the PKK's use of political violence, nor with its secular cadre.

The discussion above leads us to offer the following hypothesis:

- H1:

-

Religious Kurds do not differ from non-religious ones in support for the PKK as a legitimate organization representing Kurds.

Religious people may not have particularly positive attitudes toward an ex-Marxist organization, its secular political agenda as well as its secular leadership cadre. However, along with overt or covert social, economic, and political discrimination, the unwillingness of Islamic Turkish governments to go beyond individual rights such as education in mother language and the recognition of Kurdish identity in the Constitution dampens the credibility of religious AKP governments' narrative on the Kurdish conflict. More importantly, the perception of societal discrimination and socioeconomic inequality between Kurds and Turks belie Islamic brotherhood discourse that secular and most recently conservative AKP governments vehemently pursue. In contrast, the reality or its perception on the ground leads religious Kurds to view the PKK, despite its Marxist ideological background and leadership, as the only formidable force against the repressive state apparatus. For religious Kurds, while the PKK is demanding minority rights and equality in the public sphere, the Turkish state is working against them. While seeing the discrepancy between discourses of the state and its actions, religious people who demand equality across Kurds and Turks, but observe state discrimination and inter-ethnic inequality may view the PKK not as a terrorist organization, as the state narrates, but view as an organization that fights against the inter-ethnic inequality and injustices. Thus, we offer our second hypothesis:

- H2:

-

The perception of political and economic inter-inequality is likely to increase support for the PKK among religious Kurds.

RESEARCH DESIGN

To test our arguments, we utilized two original comprehensive nationally representative public-opinion surveys. The sample was drawn through multi-stage, stratified, clustered, and random sampling, using national statistical institution, TUIK. Age and gender quotas were also applied when visiting households. After running pilot studies in Istanbul, Diyarbakir, and several other provinces, face-to-face interviews were conducted with about 6,500 (2011) and 7,000 (2013) respondents, aged 18 or older, from seven regions, approximately 50 provinces, and 186 (2011) and 174 (2013) districts. The first survey was launched in early November 2011, during the final months of the Turkish government's protracted military engagement with the PKK. Because the conflict was of lesser intensity at this time than in the 1990s, it was relatively safe for us to conduct the survey. In March 2013, soon after the press release of Öcalan on calling the PKK for removing its militants out of the country during the Newroz celebrations, the PKK agreed to a ceasefire, ordered their militants to leave Turkey, and declared that they would end armed struggle against the Turkish state. The publicly announced ceasefire agreement and the peace talks provided a social and political environment for expressing support for the PKK in a face-to-face survey conducted in April 2013 was, less risky than in the past.

Fourteen percent and 17 percent of respondents identified themselves as ethnic Kurds in 2011 and 2013, respectively. For a robustness check, we also used mother language to code whether a person belonged to a Kurdish ethnic group. The results were substantially the same. The sample is 901 (2011) and 1,237 (2013) individuals with a Kurdish ethnic identity who reside across the country.

Dependent and Independent Variables

The first question was: “Do you think that the PKK is a terrorist organization?” The second question was: “Do you think that the PKK represents Kurds?” The respondents answered these questions with “Yes,” “No,” or “No answer/No idea.” However, these two questions might not capture full support for the PKK separately; for example, people may consider the PKK not a terrorist organization and still believe that it does not represent Kurds. That's why we created a dependent variable out of these two questions. Our dependent variable captures the possibility of those who view the PKK not a terrorist organization but who believe that the PKK does represent Kurds.Footnote 4 If a respondent affirmed that the PKK is not a terrorist organization and it represents Kurds, our newly created variable is coded as 1. All other options are coded as 0.

Our main independent variable is religiosity. We focus on its two dimensions, namely individual piety and public religiosity (see also Karakoç and Bașkan Reference Karakoç and Bașkan2012). According to orthodox Islam, there are five pillars of religion that a Muslim is required to perform. The first one is the declaration of faith; two of them are required only for those who are non-poor, such as alms-giving and doing a pilgrimage to Mecca. The two remaining pillars are required for all Muslims; praying five times a day and fasting. To operationalize religiosity, respondents were asked four questions: “Do you perform prayers five times a day?” and “Do you fast each day of Ramadan every year?” To capture attitudes toward the role of religion in public sphere, we also asked two other questions: “Should headscarves be allowed in schools, including primary and high schools?” and “Should female civil servants and public employees such as judges, prosecutors, and teachers be allowed to wear headscarves during work time?” Then, based on our suspicion that these four questions measure different dimensions of religiosity, we ran factor analysis (see Appendix) to see whether they had high loadings on the same religious commitment factor. We found that the first two and the last two questions indeed measure different dimensions of religious commitment. We then created an index from these questions, calling the first one private religiosity and the second one can be labeled as public religiosity, that is to say, attitudes toward religion in public space.Footnote 5 Each index ranges from 0 (none to low religiosity) to 2 (high religiosity).

Unlike other studies that measure grievances with proxies such as low income, education or unemployed, this study is particularly interested in the impact of the perception of state discrimination against Kurds and inter-ethnic socioeconomic inequality. Thus, using the responses to the following question would be quite appropriate for the former: “In your opinion, do you think that the state discriminates against Kurds?” The response is dichotomous, 1 (Yes) and 0 (No). As for the latter, we used only the 2013 survey because the 2011 survey did not include the socioeconomic equality question: “In your opinion, do Kurds have social and economic equality with Turks?” “No” answers were coded as 1; otherwise 0.

Modernization approach expects that high income and education may assimilate ethnic members into national identity, reducing sympathy toward rebel organization. However, studies on nationalism also expect that middle and higher income and educated minorities are the drives of nationalist movements and likely supporters of these movements (Hechter Reference Hechter2000; Wimmer Reference Wimmer2002). The leftist individuals are expected to have more sympathy toward a former Marxist/Leninist rebel organization. Respondents were then asked: “In terms of ideological orientation, there has been a tradition of right—left—center in Turkey. Ideologically, how would you define yourself on this scale?” The scale ranges from 1 (extreme left), 2 (left), 3 (center), 4 (right), to 5 (extreme right). In this analysis, we recoded the scales as follows: left (1 and 2), center (3), and right (4 and 5). In the analysis, ” the right” was used as a reference category.

One might argue that ethnic minority support of a rebel group is not about ideology or religion, but the strength of cultural-nationalistic attitudes minorities hold. Therefore, respondents were asked the following questions across the country: (1) Should there be public schools in which all courses are held in Kurdish? (2) Should the Kurdish language be offered as an optional course in public schools? (3) Should the names of cities, towns, and villages be in Kurdish? (4) Should sermons in mosques be conducted in Kurdish? We thus created a combined index; Cronbach's αs for the 2011 and the 2013 surveys were 0.82 and 0.81, respectively, showing that the index has significant internal consistency.Footnote 6 This index represents cultural demands of Kurds, and thus we called it cultural nationalism.

We also used other covariates in our models. We expect that rebel groups are more likely to appeal to younger people (Hayes and McAllister Reference Hayes and McAllister2005). Not all Kurds are Sunni; a minority belongs to the Alevi religious identity.Footnote 7 The indifferent and even condoning reactions of the state against the 1993 Sivas massacred by radical Sunni groups and at the same time the rise of Islamic movements especially created a rapprochement between Alevi Kurds and the PKK in the 1990s. However, at the same time, pro-religious discourse and actions by the same Kurdish actors in recent years to appeal to traditional Sunni Kurdish population may have created reluctance toward the latter among the former (Çelik Reference Çelik2003). That is why we do not have a directional hypothesis regarding Alevi Kurds. We controlled for the possible impact of several other factors, such as a residence (rural-urban), unemployment and gender. Descriptive statistics and the operationalization of variables in the models are available in the online Supplementary Appendix.

RESULTS

Table 1 presents our descriptive statistics on key variables that make up our dependent variable. Compared to the 2011 survey, the 2013 survey shows that fewer Kurds consider the PKK a terrorist organization (a 4% decrease), and more people feel that the PKK represents Kurds (a 23% increase). Moreover, “no response/do not know” answers decreased from 5 percent and 4 percent to 2 percent and half percent, respectively.Footnote 8 We find that 27 and 45% of Kurds displayed their support for PKK in 2011 and 2013, respectively. We conjecture that the observed surge in positive attitudes toward the PKK found in the 2013 survey derives from the ceasefire and peace talks created as well as the Uludere (Roboski) massacre on December 28, 2011, which has created significant social and political trauma. No serious prosecution toward those in the military who ordered the killing of 34 people, mostly teenager in this event, can be another reason for increased support toward the PKK in the last survey.

Table 1. Attitudes toward the PKK among Kurds

We turn to our multivariate models to test our hypotheses. Due to the dichotomous nature of our dependent variable, this study uses a logistic regression with robust standard errors. Overall, we find private, and public religiosity does not reduce or increase popular support for the PKK. The perception of inter-ethnic socioeconomic inequality increases the impacts of both private religiosity and public religiosity on support for the PKK. As for the state discrimination against Kurds, the results are only significant for the 2011 survey, which lacks the inter-ethnic inequality question. The perception of inter-ethnic inequality that only the 2013 survey asks has a similar effect.

Table 2 presents our results. We begin with the other independent variables before we investigate the main findings in detail. The cultural-nationalism variable continuously exerts a significant influence on support for PKK. Compared to right-wing Kurds, leftist Kurds hold a more positive perception of the PKK across the models. Kurds in the southeastern part of Turkey are likely to hold positive attitudes only for the 2013 model.

Table 2. Religiosity and support for the PKK

Note: Exponentiated coefficients, standard errors are in parentheses.

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 (two-tailed test).

As for the other variables (Alevi origin, education, age, income, gender, and unemployment), they yield varying effects across the 2011 and 2013 surveys. Being an Alevi Kurd increases support for the PKK only in the 2013 survey but exerts no significant impact on the full model for 2011. Gender and income do not have statistically significant impact on support for the PKK in the models based on both surveys. Support for the PKK transcends gender and income differences. Kurds with higher education are not likely to support the PKK for both models. Those who agree with the statement that the state discriminates against Kurds are more likely to view the PKK as a legitimate organization. This finding is similar to Tezcür (Reference Tezcür2016) who found that districts with higher discrimination and violence are associated with higher participation in PKK.

Does religiosity reduce support for the PKK? The results are surprising and important. Private religiosity exerts a positive impact, but not statistically significant in both models (however, statistically significant at p < 0.1) while public religiosity has a similar statistically insignificant impact. Overall, the findings suggest that religious people are not distinguishable from non-religious people in terms of popular support for the PKK.Footnote 9

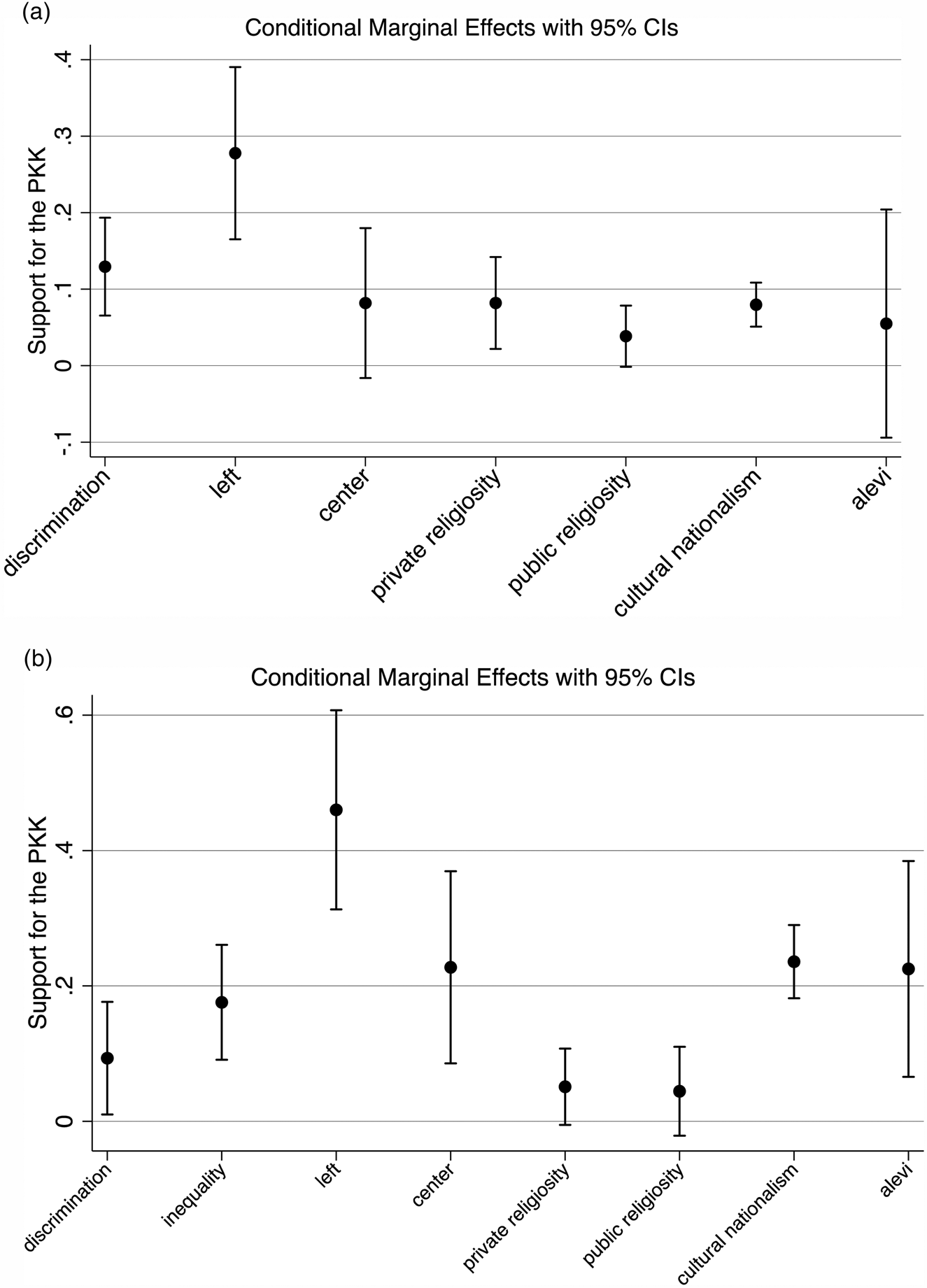

To interpret the results and determine the substantial effect of the variables of interest for our dependent variable, we also calculated the average marginal effects for both surveys, presented by Figures 1a and 1b. These figures show that the increase in the predicted probability of private religiosity for the PKK support is 9 and 3% in the surveys, respectively. The average marginal effect of public religiosity on support for the PKK for both surveys is not statistically significant: Religiosity does not hinder popular support for the PKK.

Figure 1. Marginal effects of explanatory variables. (a) Support for the PKK (2011). (b) Support for the PKK (2013).

The findings suggest that the predicted probability of support for the PKK is 13% higher for the 2011 survey and 9% higher for the 2013 survey for those who perceive that the state discriminates against Kurds. For people who perceive socioeconomic inter-ethnic inequality, the predicted probability for the support for the PKK is 11% higher than for those who believe that the inter-equality exists. In addition, the increase in the predicted probability of cultural nationalism for the 2011 and 2013 surveys is 8 and 16%, respectively. For Kurds on the left, the predicted probability is 28 and 46% higher compared to the rightists in the 2011 and 2013 surveys, respectively. This probability is relatively low for centrists, 8 (statistically insignificant) in 2011 and 21% higher in 2013.

To test our second hypothesis, we created interaction variables between religiosity and political discrimination and inter-ethnic inequality variables and reran the models with all other variables.Footnote 10 Keeping all other variables and varying categories for key variables, we created predicted probabilities for each survey year. We start with the 2011 survey year that only includes state discrimination. Figure 2 displays the predicted probabilities with a confidence interval for private and public religiosity, conditional upon the perception of state discrimination. For those who belong to the first two categories of religiosity, observing state perception does not affect one's view toward the PKK. However, those practicing both pillars of religion are likely to support the PKK if they perceive state discrimination against Kurds. Figure 2a shows that for the latter, the probability of supporting the PKK is 0.27, more than doubling for those who do not perceive discrimination, 0.10. Turning to public religiosity (Figure 2b), we reach to similar results: The predicted probability for support for the PKK is 0.25 for people both holding high public religiosity score and observing state discrimination toward Kurds. This figure is only 0.11 for the same religious people who do not perceive state discrimination. For other categories, the difference in predicted probabilities is statistically insignificant.

Figure 2. Religiosity by perception of discrimination and the PKK (2011). (a) The Impact of private religiosity by discrimination. (b) The Impact of public religiosity by discrimination.

Moving to the 2013 survey, Figure 3a and 3b suggests that the predicted probabilities of both types of religiosity are not statically different, regardless of whether one perceives state discrimination or not. It indicates that including inter-ethnic inequality measures removes some variation from the effect of the interaction variable. To see whether this is the case or not, we calculated the predicted probabilities of our key variables in the 2013 model, removing inter-ethnic inequality measure. The results confirm our suspicion. The predicted probabilities of those with middle category and high religiosity for both categories are statistically significant and much higher than those who do not perceive state discrimination (not shown here).

Figure 3. Religiosity by discrimination and inequality and the PKK (2013). (a) The Impact of private religiosity by discrimination. (b) The Impact of public religiosity by discrimination. (c) The Impact of private religiosity by inter-ethnic inequality. (d) The Impact of public religiosity by inter-ethnic inequality.

As for the modifying effect of inter-ethnic socioeconomic inequality on religiosity, the result partly confirms our hypothesis. Figure 3c shows that for those who do not perceive inter-ethnic inequality between Kurds and Kurds, the predicted probabilities for supporting the PKK remain around 0.28, regardless of the level of private religiosity. However, among those who perceive inequality, the predicted probability becomes 0.44 and 0.51 for the middle- and high-private religiosity. Figure 3d suggests that the predicted probability reaches 0.49 for those with the high public religiosity score, much higher than those who do not perceive the inequality, 0.28.

CONCLUSION

Taking advantage of low-intensity civil war before the ceasefire and the relatively calmer security context after the initiation of peace negotiations between the Turkish state and the PKK, we utilized two original surveys to bring new insights and information to understand the determinants of support for a rebel organization. Unlike most of the literature on religion and violence focusing on the relationship between religious and ethnic fractionalization and civil war, this study investigates how ethnic minority members view an ethnic insurgent organization and whether religiosity restrains support for it. The findings suggest that scholars and policy-makers should not overestimate the impact of co-religiosity or religiosity in undermining popular support for the insurgency. Unlike Zic (Reference Zic2017) argues, pious people do not choose a religious actor over a secular one as a result of insecurities or traumas associated with the conflict. Their religiosity does not hinder their support for a secular rebel organization. In this respect, this study confirms Johansen (Reference Johansen1997) who argues that every generation reconstructs and reinterprets religious text, as social and political context change. It also speaks to the earlier studies suggesting that civil wars may ethnicize religious identity and secularize political choices (Aspinall Reference Aspinall2009; Gurses Reference Gurses2018), unlike Toft (Reference Toft2007, 103) who argues that religion shapes (ethnic) identity.

Similar to studies on indigenous groups in Latin America or the Catalans of Spain (Guibernau Reference Guibernau2006; Van Cott Reference Van Cott2007), our findings show a strong affiliation between ethnic groups and leftist ideology. It is interesting that this relationship is not mutually exclusive as in terms of giving support for a rebel group, even though PKK leadership has an exclusively left-leaning ideological position (Marcus Reference Marcus2007). As discussed above, the ethnization (Kurdification) of religion,Footnote 11 along with the transformation of rebel organization into a religion-friendly one, mostly considered as a strategic move, has expanded the popular base of the PKK among religious people, while at the same time appealing to Kurds with left-leaning ideological stance.

This study also challenges the modernization approach or the assimilationist perspective that expects that higher income or educated Kurds will be more likely to accept the political status quo and refrain from supporting rebel movement. The findings add to the discussion on whether political or economic grievances matter for ethnic or nonethnic civil war (Sambanis Reference Sambanis2001) or to what extent political discrimination affects secessionist civil wars (Regan and Norton Reference Regan and Norton2005; Walter Reference Walter2006). They suggest that economic grievances caused by an ethnic group's perception of inter-ethnic inequality should not be overlooked in examining support for a rebel group. As our research shows, members of Kurdish minority who perceive political discrimination and socioeconomic inequalities exist between Kurds and the rest of society cultivate positive attitudes toward the PKK.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755048319000312