INTRODUCTION

This study considers the sources of evangelical support for Israel in the United States, utilizing an original survey of evangelical and born-again respondents. Our primary goal is to statistically assess the relative importance of theological/eschatological, cultural, social, and political determinants of evangelical support for Israel. We find that evangelical support for Israel is driven by respondents' beliefs rooted in evangelical Christian theology and by their feeling of cultural and religious affinity with Jews, rather than geopolitical/security concerns, feelings of guilt for historical persecution of Jews at the hands of Christians, or feeling of commonality on the basis of political/democratic institutions.

However, and counter to other studies which argue that evangelical support for Israel is driven predominantly by religious beliefs rooted in evangelical eschatology and Biblical literalism, our results show that the three strongest predictors of support for Israel are the respondent's age, opinion of Jews, and socialization (frequency of hearing other evangelicals talking about Israel). One especially interesting finding of this analysis is that there are significant differences in pro-Israel sentiment between 18 and 29 years old and older evangelicals and that these differences are not driven by the fact that the younger evangelicals are less religious (in fact, we find the contrary).

From the late 1970s, white evangelicals have been heavily involved in American politics, and they are mostly identified with the Republican Party. Their political agenda is almost entirely domestic in its scope and focuses predominantly on “family issues,” such as prayer in schools, anti-abortion policies, and preservation of the traditional family. Claassen found that race was the key issue for white evangelicals' realignment with the GOP (Claassen Reference Claassen2011). While evangelicals have a fairly narrow international agenda, the support for the State of Israel is at the top of their priorities. In this study, we seek to understand the sources of evangelical support for Israel, utilizing an original survey of 1,000 evangelical and born-again respondents, conducted between April 3 and April 10, 2018.

The fact that evangelical Christians express such interest and a sense of shared destiny with Jews and Israel is both fascinating and peculiar given the long-standing anti-Semitism embraced by many Christians and their secular and religious authorities. A shift away from historical anti-Semitism began during the early days of the Protestant Reformation. Some Protestant leaders expressed their sympathy with Jews, thus moving away from the established attitude of the Roman Catholic Church and from Martin Luther's anti-Semitism (Ariel Reference Ariel2013, 15–34). Evangelism became a common name for a revival that swept the English-speaking world in the late 18th century. Evangelicals' interest in Jews grew even stronger with the rise of the Zionist movement. Among its early supporters were prominent evangelical figures like William Hechler, who was a personal assistant of Theodor Herzl's, the founder of modern Zionism (Goldman Reference Goldman2009, 88–136). Scholars even showed that the Balfour Declaration (1917), the British promise to assist establishing a Jewish national homeland in Palestine, was inspired by philo-semiteFootnote 2 evangelical sentiment (Stein Reference Stein1961; Schneer Reference Schneer2000). Evangelical support and interest began before the formation of the State of Israel, but it has grown much greater since the declaration of the State of Israel on May 14, 1948.

Israel's success and the expansion of its borders, including the conquest of Jerusalem and the Temple Mount after the 1967 Six-Day War, triggered another wave of evangelical interest in Israel. The evangelical theologians' interest in the Israeli victory was connected to the predictions about the second coming of Jesus Christ (Gorenberg Reference Gorenberg2000). For example, Hal Lindsey, an American evangelical preacher, argued in his best-selling book, The Late Great Planet Earth (Reference Lindsey1970, 41–47), which sold more than 10 million copies, that Jesus' Second Coming would take place within 40 years from the establishment of the State of Israel (Weber Reference Weber1987, 13–42). A similar theme that connects Israel's success to the imminent Second Coming was also articulated in the Left Behind books, a series of 16 best-selling religious novels, by Tim LaHaye and Jerry B. Jenkins (1995–2007). In these novels, Jews and the State of Israel play a central role in the End of Days events (Ariel Reference Ariel2013, 46–53). These books demonstrate a popularized manifestation of evangelical support of Israel and have spawned a new generation of end-time believers, which has caught the eye of some researchers (Gribben and Sweetnam Reference Gribben and Sweetnam2011).

Most of the scholarship on the evangelical support of Jews and the State of Israel, including its missionary activities toward Jews, is largely the product of historians and scholars of religious studies. In these publications, the subject is researched from archives and interviews with evangelical leadership, and typically entails content analysis of the statements of different evangelical leaders' speeches. The study of evangelical grassroots attitudes of and support for Jews and the State of Israel has been limited so far, with only a handful of surveys (Pew Research Center 2014; The Brookings Institution 2015; LifeWay 2017; Gallup 2018) and academic publications (Mayer Reference Mayer2004; Baumgartner, Francia, and Morris Reference Baumgartner, Francia and Morris2008; Gries Reference Gries2015). Our survey contributes to this growing body of public opinion research on evangelical attitudes and our study provides one of the first statistical analyses of the causes of evangelical support for Israel.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. We begin with an introduction of the motivations of evangelicals in support of Israel, followed by an introduction to the survey and some of its descriptive results. The study then turns to the operationalization of variables and statistical analysis, which tests hypotheses regarding the potential motivations for the support of Israel discussed below. We finish with the interpretation and discussion of the statistical results and identify venues for future research.

EVANGELICAL MOTIVATIONS

The literature on the evangelical support for Israel identifies several potential sources, which can be grouped into the following categories:

1. Eschatology—Evangelicals adhere to a Christian school of thought called pre-millennial dispensationalism. According to this philosophy, the second coming of Christ is an imminent event that will take place in several stages. In the first stage, Jesus will reappear in heaven, but will not descend to earth. In heaven, he will meet the true believers—those who were “born again” by adopting Christ as their personal savior. In an act known as “the rapture,” these believers will be miraculously drawn up to Jesus from the earth, while true believers who died prior to the appearance of the Messiah will be resurrected from the dead and join Jesus. All of this is expected to happen in the near future, although evangelical writings do not provide a specific timeframe in most cases. For Jews, this will be “a time of trouble for Jacob” (Jer. 30:7). Despite returning to their homeland, prior to or during this period, Jews will be considered “lacking in faith” because they will not have accepted Christ as their Messiah (Boyer Reference Boyer1992, 254–90).

Therefore, Jewish presence in what is currently identified as the State of Israel and the occupied Palestinian territories will not be the “kingdom of God,” but rather just a stage in the developments that will precede the coming of the Messiah. During the period of “the great tribulation,” there will arise a rulerFootnote 3—the Antichrist—who will pass himself off as the true Messiah and be accepted by Jews as their redeemer. Taking over the rebuilt Temple, the Antichrist will institute a reign of terror. Jews who accept the kingdom of Christ during this period will be persecuted by the followers of the false messiah, and some of them will even be killed. There will be a series of attempted invasions of the Holy Land from all corners of the world. The period of the great tribulation will end with the return of Christ to earth, together with his true believers, to establish his kingdom. He will defeat the Antichrist, establish a regime of justice throughout the world, and make Jerusalem his capital. During these anticipated events, most Jews would open their hearts to accept Jesus as their Messiah (Weber Reference Weber1987; Ariel Reference Ariel2013, 9–21; Sturm Reference Sturm, Dittmer and Sturm2010).

There might be more than one way to interpret the prophesies of the Book of Revelation and the prophetic literature, but the evangelicals who prescribe to pre-millennial dispensationalism connect the establishment of the State of Israel and events such as Israel's victory in the Six Day War and its conquest of the Temple Mount as a temporal fulfillment of prophecy regarding the Second Coming of Christ. Thus, one potential evangelical motivation to support Israel is grounded in messianic expectations and in participation in the divine plan for redemption (Gorenberg Reference Gorenberg2000).

All monotheistic religions contain eschatological visions of End Days. In most times, these visions have no significant meaning to the life and well-being of the community of believers. However, at certain points, these visions can become central, thus pushing the true believers to action in anticipation of imminent redemption. On the spectrum of “hot” or “cold,” we can identify “hot” as active anticipation for a redemption that would transform humanity and bring about an end of times. These “hot” episodes are followed by long “cold” periods of time, sometimes even blended with negative attitudes toward messianism, in which the possibility of a sudden transition to the End Days exists, but the general public takes no action to hasten it, or even thinks of it as reasonably possible (Talmon Reference Talmon1966; Wessinger Reference Wessinger2000; Landes Reference Landes2011). An example of “hot” messianism can be found in Cohn (Reference Cohn1957) research which shows how several movements rose to significance in Medieval Europe, expecting the Second Coming of Christ as an imminent event. Some of them have concentrated their attention on the First Crusade (1096–9), which was viewed as a holy war that would lead to the End Days. During the 17th century, a mass movement developed among Jews, who identified Shabetai Zvi as the Jewish messiah (Scholem Reference Scholem1973). In the history on American evangelism, a notable example of “hot” messianism is the Millerites movement, based on the leadership of William Miller, that expected the Second Coming for the year 1843 and later recalculated their predictions to 1844 (Rowe Reference Rowe1985). The Jehovah Witnesses is another contemporary example, albeit not of an evangelical movement, steeped with messianic expectations that already calculated the End six times (Zygmunt Reference Zygmunt1970). Olson (Reference Olson2018) argues that the 1967 Arab-Israeli war and the Israeli capture of Jerusalem brought about “hot” messianism amongst many American evangelicals, as discussed earlier in the writings of Hal Lindsey. These “hot” episodes of messianic expectations are not the normal state of religion that is mostly “cold” toward acute messianism.

2. Blessings—One of the fundamental principles of evangelical Christianity is Biblical literalism.Footnote 4 Genesis 12:3 mentions that God would offer a blessing to the nations who would support Abraham's offspring: “I will bless those who bless you, and whoever curses you I will curse; and all peoples on earth will be blessed through you.” In Allies for Armageddon, Clark (Reference Clark2007: 263) suggests that a fear of the wrath of God plays a major role in Christian Zionist support for Israel: “if America abandons Israel, then God will cancel America's most Divinely Favored Nation status.” Another example is from the work of journalist Koenig (Reference Koenig2011), who prepared a study claiming that a statistical correlation can be seen between American pressure on Israel to make territorial compromises and natural disasters in the United States. Koenig claims that within 24 hours of an American president pressuring Israel, a natural disaster (such as floods, hurricanes, tornados, wildfires, or earthquakes) or terrorist attack takes place in the United States. This line of thinking led some evangelicals to argue that Israel's 2005 Disengagement Plan and the evacuation of the Gush Katif settlement in Gaza brought the destruction from the hurricane Katrina onto the United States (Berkowitz Reference Berkowitz2015). Thus, evangelicals believe that supporting Israel could bring blessings on them, as promised by God, and abandoning Israel will be detrimental to America's future prosperity.

3. A Belief that Jews are God's Chosen People—Another aspect of this literal reading of the Bible includes a belief that Jews are the offspring of Abraham and are thus God's chosen people. Evangelical preachers usually oppose the “replacement theology” that argues that Jews lost their election on earth after rejecting Jesus as the Messiah. By rejecting replacement theology, the evangelical message stands in contrast to a long-standing Christian belief that God is finished with the Jewish people, that all of his promises of good to Israel have been transferred to the Church. Christian Zionists refer to this belief as “supersessionism” and consider it a profound theological error (Spector Reference Spector2009, 21–22; Vlach Reference Vlach2009). For example, Pastor John Hagee, leader of Christians United For Israel, said, “It is time that Christians remove the self-imposed scales from our eyes placed there by the sanctimonious teachings of the replacement theology. God never rejected the Jews or replaced them because they could not see Jesus as Messiah. God still loves and cherishes the Jewish people and has a glorious future in store for them” (Hagee Reference Hagee2007, 156).

The three potential reasons for evangelical support for Jews and Israel discussed above are deeply rooted in evangelical theology. Beyond these explanations, we consider several other potential determinants of evangelical attitudes. These explanations are secular in scope and concern political, cultural, and historical reasons for evangelical support for Israel.

4. Guilt—Another potential rationalization for supporting Israel may come from a sense of guilt, rooted in the belief that the long history of anti-Semitism in Christianity eventually culminated in the horrors of the Holocaust. An example of this sentiment can be seen in the preaching of Pastor John Hagee, who declared that anti-Semitism that led to the Holocaust has its origins in Christianity: “A thread connects the crusades, the Spanish Inquisition, Martin Luther's attacks on the Jews, Adolf Hitler, and the Final Solution. All these acts were committed by baptized Christians” (Hagee Reference Hagee2007, 6). As Hagee points out, European history of anti-Semitism may therefore provide a strong incentive to evangelicals to support Israel in a mea culpa type of reaction. This sense of atonement for previous sins of the Christian nations may be further amplified by a belief in God's blessings (curse) for those who support (attack/oppose) Jews and Israel, which we discussed earlier.

5. Shared Political Values—Israel enjoys widespread support by the American public and the political elite on both the left and the right, although this sentiment is weakening among liberals (Baumgartner, Francia, and Morris Reference Baumgartner, Francia and Morris2008; Cavari Reference Cavari2013; Gries Reference Gries2015). A Gallup poll conducted in 2018 showed that Americans' stance on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is as strongly pro-Israel as at any time in Gallup's three-decade trend. Sixty-four percent say that their sympathies in the dispute lie more with the Israelis, tying for the highest levels of support previously recorded in 2013 and 1991 (Saad Reference Saad2018). The annual conventions by the American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC), a lobbying group that advocates pro-Israel policies, are an expression of that support, where politicians from across the political spectrum come to express their support for Israel. For example, in 2016, the Democratic presidential candidate Hillary Clinton gave a speech at the convention where she said that “we've always shared an unwavering, unshakable commitment to our alliance (with Israel)” (Beckwith Reference Beckwith2016). It is undeniable that Israelis and Americans share many (if not most) Western socioeconomic and political foundations.

Thus, it would not be farfetched to argue that evangelicals may see Israel as an American ally because both societies share a set of common political principles and democratic practices, such as competitive politics, rule of law, individual liberties, free press, and limited government. As DeLay (Reference DeLay2003), a former House Majority Leader and an evangelical Christian, emphasized this sense of political affinity or kinship in his speech to the Israeli Knesset on July 30, 2003: “The solidarity between the United States and Israel is deeper than the various interests we share. It goes to the very nature of man, to the endowment of our God-given rights to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. It is the universal solidarity of freedom.” This “solidarity of freedoms” and democratic values could be a powerful reason for evangelicals to express high levels of support for America's only democratic ally in the Middle East—Israel.

6. Common Geopolitical and Security Concerns—Evangelicals may also perceive Israel as an ally due to shared geopolitical and strategic interests. Accordingly, support for Israel can reflect a belief that Israel is America's best ally in an important but volatile part of the world. In that regard, many evangelicals may see Israel as a partner in containing Iran and in fighting radical Islam (Spector Reference Spector2009, 76–110). Sturm (Reference Sturm, Dittmer and Sturm2010) argues that Muslims replaced the Soviet Union as America's and God's enemies, thus reshaping evangelicals' foreign policy priorities. From this perspective, as Gries (Reference Gries2015, 72) notes, “the Israelis are on the frontline of a battle to keep the Palestinians and other Muslims from upsetting the global pecking order.”

In addition to shared Israeli and American geo-political concerns, evangelicals may see Israel as a guarantor of Western civilization's security in the Middle East, in general, and a guarantor of Christian access to the holy sites in Israel and the Occupied Territories, more specifically. Such concerns for the physical safety of Christians visiting the Holy Land and the security of Christian religious sites may prompt evangelicals to support the State of Israel.

7. Shared Cultural and Religious Values—Finally, and similar to the political kinship argument above, one could argue that evangelical support for Israel is rooted in a belief in a shared Western culture, including religion, ethics, traditions and customs, and etiquette. From this perspective, supporting Israel can reflect a sense of cultural kinship based on feelings of shared cultural and ethical values between Jews and Christians (Silk Reference Silk1984).

There is a lack of scholarly consensus on which of the factors identified above are the primary drivers of evangelical support for Israel. Some scholars put more emphasis on the evangelical belief that supporting Jews would bring blessings on them and thus view it more as a philo-Semite sentiment (Inbari Reference Inbari2012, 151–84). Other scholars go in the completely opposite direction and see the motivations of conservative evangelicals in supporting Israel as hypocritical and as bordering on anti-Semitic, because evangelicals believe that there would be a mass conversion of Jews after the Second Coming, which is considered as an imminent event (Abraham and Boer Reference Abraham and Boer2009; Michaelson Reference Michaelson2018).

Given that with the possible exception of Jewish Americans, the evangelicals are the most ardent supporters of pro-Israeli U.S. foreign policy (Mayer Reference Mayer2004), it is important to understand whether evangelical support is rooted predominantly in religious beliefs or in more broadly-conceived cultural and political affinity and common geopolitical interests, or both. Our paper aims to fill this gap by using a new survey of evangelical and born-again Christians.Footnote 5

THE SURVEY

We analyze the sources of evangelical support for Israel using original survey data, compiled for us by LifeWay Research, a national polling company that specializes in surveying attitudes of various Christian communities.

The survey was conducted on April 3–10, 2018.Footnote 6 The sample was screened to include only those who consider themselves an evangelical and/or born-again Christians.Footnote 7 A demographically balanced online panel was used. Maximum quotas and slight weights were used for gender, region, age, ethnicity, and education to more accurately reflect the evangelical population in the United States (as defined by 2014 Pew Religious Landscape Survey). A total of 2,754 respondents started the survey, 1,694 were screened out by quotas or the screening criteria, and 60 were incomplete or dirty. The completed sample is 1,000 surveys. The sample provides 95% confidence that the sampling error does not exceed plus or minus 3.27%, accounting for weights.

Initially, we expected to conduct a set of telephone or face-to-face surveys, but chose to implement our survey online instead. This decision was driven by several reasons. First, completing a survey online significantly reduced the costs and the amount of time needed to generate a nationally-representative sample. Second, as Gries (Reference Gries2015) points out, completing a survey online in the privacy of one's own home potentially reduces biases or self-presentation effects that are more likely to manifest themselves in telephone or face-to-face interviews, especially when controversial or delicate topics are addressed in the survey. Third, all of our questions are measured on a five- or seven-point scale, and such questions are easier to employ via an online survey rather than over the telephone because an online format allows for easier use of categorical rating scales. In sum, utilizing an online format helped us decrease costs and time needed to carry out this survey, as well as reduce measurement error.

WHO ARE THE EVANGELICAL RESPONDENTS AND WHAT VIEWS DO THEY HOLD?

In our survey, the majority of evangelicals and born-again Christians are white (65% of the sample), concentrated mostly in the Southeast (38.3%) and the Midwest (22.5%), and are most likely to hold a high school diploma (37%) or have “some college” experience (29.8%), without obtaining either an associate or baccalaureate degree. They live predominantly in rural (37%) and suburban locations (42%), and their mean household income is roughly $40,700. Sixty-one percent of the respondents in our survey are female.Footnote 8 An average age of our respondent is 49.3 years of age and 57.3% of the respondents are married. As expected, our respondents exhibit a relatively high level of religiosity (demonstrated by the frequency of church attendance and frequency of reading the Bible) with over a half reporting attending church at least once a week and reading the Bible at least twice a week (see Table A1 below).

One of the principal findings of LifeWay Research's Evangelical Attitudes Toward Israel Research Study (2017) was noticeably lower levels of support for Israel among young evangelicals. This study shows that American evangelicals under 35 are less likely than their elders to offer strong support for Israel and are more likely to have a critical view of the country and its policies. These findings prompted us to examine this age group more carefully in our research. The authors of the LifeWay Research (2017) note that “The majority of those with Evangelical beliefs attribute the primary reason for their support of Israel to the Bible” (p. 4) and that frequent church attendance is linked with strong support for Israel (p. 18). Are younger evangelicals less supportive of Israel simply because they are less frequently attending church and/or reading the Bible?

Our survey results do not lend support to this hypothesis. The data in Table A1 show that lower rates of church attendance and Bible readership are not likely to be the reason why younger evangelicals (18–29 years old respondents) express lower levels of support for Israel than other age groups. In fact, 18–29 years old evangelical respondents have lower, rather than higher, rates of “seldom” or “never” attending church or reading the Bible than the older (30+) evangelical respondents. The differences are particularly pronounced in the “seldom” category of responses.

Our results regarding ideological positions of the evangelical and born-again Christians are consistent with other surveys and with the voting patterns of the evangelicals in the 2016 presidential elections (see Table A2). Exit polls after the election showed that only about 16% of evangelicals voted for the Democratic candidate, Hillary Clinton (Baily Reference Baily2016). Similarly, in our survey, only 17.1% described themselves as “slightly liberal,” “liberal,” and “extremely liberal.” The vast majority of the respondents indicated a preference for conservatism (55.9%).

It is noteworthy—and this will become more relevant in the analysis of evangelical attitudes toward Israel and Israeli-Palestinian conflict later in this paper—that ideological preferences of the 18–29 years old reflect more of a normal distribution, with moderates/centrists comprising the largest proportion (30.36%) of this cohort. The older generations, on the other hand, are more likely to adopt a more conservative platform, with the largest proportion of the respondents (32.73%) picking the “conservative” response category.

The survey also uncovered an interesting contrast between the opinions of different evangelical age cohorts toward Jews and Muslims. Data show that 18–29 years old respondents manifest much warmer feelings toward Muslims than the older evangelicals (see Table A3). A total of 46.33% of 18–29 years old express “good” or “very good” opinion of Muslims, while only 21.14% of older evangelicals responded with positive feelings toward Muslims. Darrell Bock, a bible scholar and professor at the Dallas Theological Seminary, argues that “What drives a millennial are justice questions—and there are real questions related to justice and how Israel handles the Palestinians” (Connelly Reference Connelly2016). Perhaps, the differences in support for Muslims that we observe here are linked to different conceptions of justice held by the different age groups, with younger evangelicals more likely to perceive the Palestinians as victims of Israeli occupation and maltreatment. No such cohort differences were discovered regarding respondents' feelings toward Jews, with 65% of both cohorts expressing a positive view of Jews, and with another 22.6% (18–29 years old) and 25.76% (30-year-old and older respondents) expressing a neutral attitude.

MAPPING EVANGELICAL AND BORN-AGAIN CHRISTIAN SUPPORT FOR ISRAEL: THE DEPENDENT VARIABLE

We chose to employ a relative measure of support for Israel (vis-à-vis Palestinians), rather than a separate set of measures of support for Palestinians and Israel. We did so, in part, because we wanted the respondents to assess their degree of support for these actors in relation to each other rather than in the abstract. The existing literature supports this choice. For example, Gries (Reference Gries2015) found that Pentecostals, white Baptists, and other white evangelical Protestants displayed the largest gaps (with the exception of American Jews) between their warmth toward Israel and their coolness toward Palestinians. In addition, Mayer (Reference Mayer2004, 697) argues that “the comparative favoritism for Israel is greatly lessened when respondents are not asked to choose only between Israel and the Palestinians, but given an option for neutrality.” In order to capture this potential effect, we also employ a neutral category in our survey question.

The dependent variable in this study is based on the following question: “Where do you put your support?” The respondent was offered the following range of responses: (1) Very Strong Support for Palestinians; (2) Support Palestinians; (3) Lean Toward Support for Palestinians; (4) = Support Neither; (5) Lean Toward Support for Israel; (6) Support Israel; (7) Very Strong Support for Israel; and (8) Don't Know.

We recoded the original variable in the following manner: (1) Support Palestinians (1.51%); (2) Lean Toward Support for Palestinians (1.28%); (3) Support Neither (22.04%); (4) Lean Toward Support for Israel (14.39%); (5) Support Israel (60.79%).Footnote 9 The “Don't Know” category was recoded with missing values to drop these observations from the data. This resulted in a drop of 138 observations, giving us 862 respondents (see Appendix 1 for descriptive statistics).

As the descriptive statistics and previous research on the subject show, evangelical and born-again Christian support for Israel is substantial. Over 75% of the respondents either lean toward supporting Israel or manifest strong or very strong support for Israel.

DETERMINANTS OF EVANGELICAL SUPPORT FOR ISRAEL

Hypotheses

First, we hypothesize that evangelicals and born-again Christians are motivated in their support for Israel by their messianic expectations of the Second Coming of Jesus Christ and by the necessity to participate in the divine plan for redemption. Since pre-millennial dispensation theology expects that the events of the Second Coming would take place in a near future that Jews would build a Temple for God prior to these events, and that, eventually, many Jews would convert to Christianity, we expect that the respondents who follow this religious belief would also express higher levels of support for Israel, because do so would contribute to the fulfillment of prophecy. We also hypothesize that evangelicals are motivated by their belief that Jews are God's chosen people due to their literal reading of scripture.

In addition, we argue that evangelicals may be motivated to support Israel if they perceive that common cultural and political institutions unite the Americans and the Israelis. We also hypothesize that evangelicals' support for Israel is rooted in their geopolitical and security concerns. If evangelicals see Israel as a guarantor of Western civilization's security in the Middle East, in general, and a guarantor of Christian access to the holy sites in Israel and the Occupied Territories, more specifically, then they are more likely to express a high degree of support for Israel.

Another potential rationalization for supporting Israel comes from a sense of guilt rooted in the long history of anti-Semitism by Christians that eventually culminated in the Holocaust. From this perspective, we hypothesize that the evangelical support for Israel is perceived to be one of the ways that Christians can right the old wrongs perpetrated against Jews by Christians.

In addition to the factors discussed above, we expect that support for Israel will be affected by the frequency with which a respondent hears other evangelicals expressing support for Israel. We hypothesize that this process of socialization, through which individuals become aware of politics, learn political facts, and form values and attitudes, is an important part of the explanation of evangelicals' support for Israel, which has been ignored by the previous studies on this subject.

Similarly, we hypothesize that respondents who exhibit a relatively high level of religiosity—demonstrated by the frequency of church attendance—should express more positive attitudes toward Israel. We expect that more frequent exposure to the message about the importance of Jews and Israel to evangelicals should promote more support for Israel because of the increased potential for socialization, which we discussed above.

A number of previous studies identified ideology and partisanship as important determinants of evangelical attitudes toward Israel and Israeli-Palestinian dispute. For example, Mayer (Reference Mayer2004) finds that evangelical Republicans are more supportive of Israel than evangelical Democrats, even after controlling for the effects of pre-millennial dispensationalism. Gries (Reference Gries2015, 73) argues that liberals are less sympathetic toward Israel than conservatives because “the greater value that liberals place on compassion and fairness contributes to their opposition to what they view as Israeli oppression of the Palestinians in the occupied territories.” Thus, we control for the respondent's political ideology and hypothesize that more conservative respondents will express higher levels of support for Israel.

This study also controls for the respondent's general opinion of Muslims and Jews. We hypothesize that negative attitudes toward Muslims and more positive attitudes toward Jews will increase a respondent's degree of support for Israel. We similarly expect that people who express neutral opinion toward both groups are also more likely to support neither Israel nor Palestinians, or only express weak level of support for Israel or Palestinians.

Finally, we control for standard demographic factors (age, education, income, gender, race/ethnicity, and region of residenceFootnote 10). However, in light of recent results reported by LifeWay Research (2017) survey, the effect of age on support for Israel is of particular interest. The authors of the LifeWay study show that young evangelicals are less attached to Israel than are the older cohorts. Accordingly, we anticipate a lower level of support for Israel among the respondents who self-identify as 18–29 years old in our survey than among the older age groups. Additionally, previous findings by Weisbord and Kazarian (Reference Weisbord and Kazarian1985) and Shapiro (Reference Shapiro2018) lead us to expect that black Americans will be less sympathetic toward Israel than are other Americans, due to the close relationship Israel developed with South Africa during the apartheid era and due to the black Americans' greater concern for racial justice. We do not have clear theoretical expectations about the impact of other demographic variables on support for Israel and therefore employ a two-tailed test of statistical significance to take into account all potential effects.

Operationalization

To measure whether theological, cultural, political, or security-related attitudes impact support for Israel, we rely on a battery of questions from our survey, which rank respondents' responses according to the following scale: (1) strongly disagree; (2) disagree; (3) somewhat disagree; (4) neither agree nor disagree; (5) somewhat agree; (6) agree; (7) strongly; and (8) don't know.Footnote 11

The theological questions included in our analysis include the following:

• I support Israel because its existence is proof of the fulfillment of prophesy regarding the nearing of Jesus' Second Coming.

• I support Israel because Jews are God's chosen people.

• I support Israel because it needs to build a temple for God on the Temple Mount in the near future.

We attempt to tap into broader cultural, political, and security-related motivations for support through the following set of questions:

• I support Israel because of my shared cultural and/or religious values.

• I support Israel because of my shared political or democratic values.

• I support Israel because it protects the holy sites and is the only guarantor of Christian access to them.

The following question looks at whether guilt (for the historic persecution of Jews by Christians) is a factor that accounts for evangelical support of Israel:

• I support Israel because Jews suffered discrimination and extermination at the hands of Christian nations in the past.

The distribution of responses to these questions appears in Table A4.

To control for potential socialization effects, we ask the respondents to estimate how often they hear other evangelicals express support for Israel. Respondents were given the following response options: (1) every week (23.3% of respondents); (2) once a month (26% of respondents); (3) seldom (35.7% of respondents); and (4) never (15% of respondents). The variable was then recoded, with higher values to indicate more frequent expressions of support.

The measurement of the remaining variables—opinion of Jews and Muslims, respondent's ideology, and standard demographic variables—has been discussed above and the summary statistics for all variables appear in Table A5. Appendix 2 provides variable descriptions and coding rules for all of the variables used in this analysis.

FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION

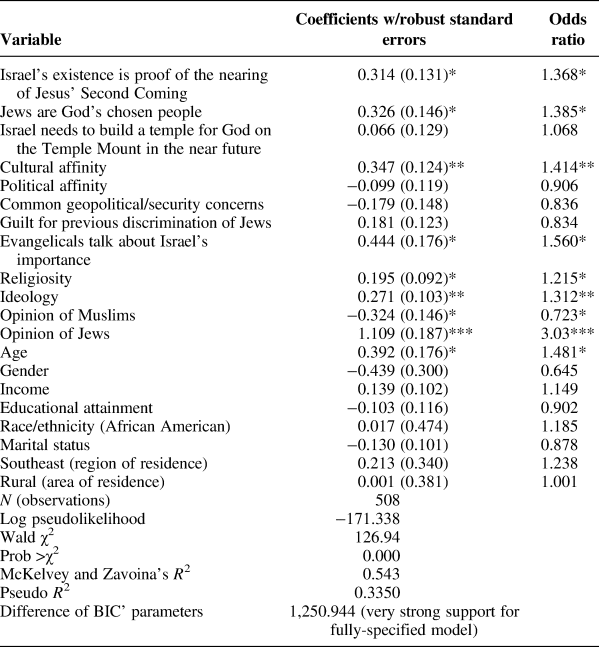

To explore the factors influencing evangelicals' support for Israel, we utilize a multivariate ordered logistic regression.Footnote 12 Sampling weights and robust standard errors are used in the analysis. All tests for parallel lines assumption (Wolf Gould, Brant, score, likelihood ratio, and Wald) were insignificant, as expected (Table A6).Footnote 13 Table A7 displays the statistical results and odds ratios for the explanatory variables.Footnote 14

As expected, the results show that evangelical support for Israel is driven by respondents' beliefs rooted in evangelical Christian theology and by their feeling of cultural and religious affinity with Jews. Hypotheses regarding geopolitical/security concerns, feelings of guilt for historical persecution of Jews at the hands of Christians, or feeling of commonality on the basis of political/democratic institutions were not supported by the data.

Respondents who stated that they support Israel to fulfill the prophesy regarding the Second Coming of Jesus Christ and because Jews are God's chosen people are more likely to manifest high levels of support for Israel than respondents who either disagreed or responded with weak support to these statements. The odds ratio shows that for one unit increase (in favor of a stronger agreement) to the statement “The State of Israel is a proof of the fulfillment of prophesy regarding the nearing of Jesus' Second Coming,” the odds of very strong or strong support for Israel (versus expressing lukewarm/weak support for Israel support for Palestinians, or expressing neutrality) are 1.368 times greater, given that the other variables in the model are held constant. Similarly, for one unit increase (e.g., from “somewhat agree” to “agree”) in support for the statement “I support Israel because Jews are God's chosen people,” the odds of a significant level of support for Israel are 1.385 times greater.

In contrast, we find no support for the hypothesis that pre-millennial dispensation theology, which expects that Jews would build a Temple for God prior to the events of the Second Coming, is a statistically significant predictor of support for Israel. The coefficient for this variable is positive, as hypothesized, but the variable fails to achieve commonly-accepted levels of statistical significance. This finding is important, since many commentators do associate evangelical support for Israel with the reconstruction of the Temple in the near future. Our results fail to find support for this evangelical motivation.

This study similarly fails to find support for political affinity and geopolitical/security concerns hypotheses. In bivariate regression, both reasons for support show positive coefficients and high levels of statistical significance, but in a fully-specified model, the effects of these variables wash out. However, we find strong support for the cultural affinity hypothesis. Perceptions of a kinship, on the basis of common cultural and religious values, play a major role in generating high support for Israel. The variable is statistically significant and for one unit increase in favor of stronger support for the cultural affinity statement, the odds of a respondent expressing strong support for Israel increase 1.414 times, with other variables held constant.

We fail to find support for the argument that evangelicals are pro-Israel due to latent feelings of guilt or responsibility for the Christian persecution of Jews in the past. The data show that this is not a significant predictor of Israel's support. While the coefficient is in the hypothesized direction, it fails to reach acceptable levels of statistical significance (although in a bivariate regression, the coefficient is positive and highly significant, as originally hypothesized).

The analysis reveals that the frequency of church attendance (religiosity), ideology (specifically, preference for a conservative point of view), and opinion of Jews and Muslims are all significant predictors of support for Israel among evangelical and born-again Christians. More frequent attendance of church and religious assemblies increases the odds of strong support for Israel by 1.215 times. Similarly, respondents who select “slightly conservative,” “conservative,” or “extremely conservative” responses to the ideology question are 1.312 times more likely to express high levels of support for Israel than the more liberal or centrist evangelicals.

Socialization is a particularly important variable in explaining evangelical support. The odds ratio of 1.56 shows that being around other evangelicals who talk about Israel and about its importance to the evangelical community is one of the most significant predictors of support for Israel, second only to the influence of positive opinion of Jews. Put simply, more frequent exposure to positive messages about Israel generates high levels of support, even taking into account the influence of other variables. Together, frequent church attendance and socializing with other pro-Israel evangelicals increase the odds of high levels of support by almost threefold (2.775 times).

However, it is worth noting that these positive effects are less pronounced for the 18–29 years old evangelicals. As we discussed earlier in the paper, and as the statistical analysis shows, age is one of the three strongest predictors of support for Israel. In particular, we find that young evangelicals are less likely to express strong support than their parents and grandparents—one unit increase in age (i.e., moving from 18–29 years old category to the 30–49 cohort, or from the latter to the 50–64 age group, and so on) also increases support for Israel 1.481 times. We also wanted to know if the effect of age was isolated to a particular age group only. To consider this possibility, we tested the impact of age on support for Israel for each age category. In a fully specified model, only 18–29 years old age category carries statistical significance (negative effect on support for Israel).Footnote 15 Thus, even though the survey shows that absenteeism or infrequent church attendance is lower among the younger cohorts than in the older age groups, the positive effects of religiosity and socialization on support are less consequential for this age group.

Perhaps, the explanation for this lies in the fact that younger respondents, as Table A2 shows, are more likely to profess “middle of the road” or centrist political positions than older respondents. Among 18–29 years old, moderates/centrists comprise the largest proportion (30.36%) of respondents, with another 29% expressing a preference for liberal positions. The older generations, by contrast, are more likely to adopt a more conservative platform, with more than 59% of the respondents picking a “slightly conservative” or a more conservative position. Only 14.6% of 30-year-old and older respondents identified with the liberal ideology. Our findings are consistent with Mayer (Reference Mayer2004) who found that the older, white, Republican respondents were most sympathetic toward Israel.

Another potential answer lies in the different conceptions of “justice” among younger and older evangelicals, particularly in regard to the Israeli-Palestinian dispute. For example, Gary Burge, a professor at Calvin Theological Seminary and former professor at Wheaton College (an evangelical university), said that “the younger generation is less likely to quote Bible passages about Jerusalem, and more concerned with ethics and treatment of the downtrodden” (quoted in Lovett Reference Lovett2018). Similarly, Darrell Bock, professor at the Dallas Theological Seminary, argues that millennials find Israeli treatment of Palestinians as inhumane and counter to their conceptions of fairness and justice (Connelly Reference Connelly2016). Our current data can only provide a tentative, and admittedly speculative, glimpse at the reason why 18–29 years old might express more support toward Palestinians over Israel, but these results are consistent with Burge and Bock's impressions and certainly merit more attention in future research.

The statistical analysis also confirms that respondents' opinion of Muslims and Jews impact their support for Israel. As we hypothesized, negative opinion of Muslims increases support for Israel, while a favorable view of Muslims reduces support for Israel by 0.723 times. Also, a favorable view of Jews has a highly statistically significant and positive impact on support for Israel. In fact, the opinion of Jews is the most significant predictor of support for Israel in our analysis, increasing the odds of registering high support by 3.03 times. While this is, in some ways, an obvious conclusion, there is an important message here. While church activities, interaction with other pro-Israel evangelicals, belief in a common Judeo-Christian culture, and theology all play their expected role in explaining evangelical support, our analysis shows that nurturing a positive opinion of Jews, irrespective of theology or other potential explanations, may be the best way for evangelical leaders to promote support for Israel among their congregations.

Finally, it is important to note that with the exception of the effects of age, no other demographic variable rose to the level of statistical significance. Our analysis shows that neither education, race and ethnicity, income, marital status, nor region or area of residence has an impact on evangelicals' levels of support. We initially expected that race and ethnicity may play a role, hypothesizing that the African-American support for Israel would be low. As Shapiro (Reference Shapiro2018) argues, “The voting patterns, emphases and styles of white and black evangelicals tend to be distinctive. African-American evangelicals are less consumed by issues like abortion, LGBT issues and the war on drugs than are their white counterparts, and more focused on issues of racial justice and poverty.” The last issue—racial justice and poverty—may certainly have an impact on black evangelical support for Israel and their perceptions of Muslims and Jews. While we did not discover the statistically significant impact of race on evangelical's support in this analysis, a more detailed examination of black evangelical views on Israeli-Palestinian dispute and of their levels of support for Israel is merited.

NOTES ON EVANGELICAL IDEOLOGY: ESCHATOLOGY AND BIBLICAL LITERALISM

In the survey, the most significant ideological statements that came up in the multivariate model were that the respondents support Israel because it fulfills the prophesy regarding the Second Coming of Jesus Christ and because Jews are God's chosen people. Thus, eschatology and Biblical literalism are important factors among evangelicals. In this section, we would like to expand upon these two ideological aspects, based on the results of the survey.

As we know, evangelical Christianity is highly influenced by the eschatological vision of pre-millennial dispensationalism. Thus, we asked the respondents their attitude toward the following statements:

• The State of Israel is a proof of the fulfillment of prophesy regarding the nearing of Jesus' Second Coming.

• I support Israel because I believe it will lead to the Second Coming of Jesus.

As the responses indicate, there is an overwhelming support for the notion that the State of Israel is connected to the idea of the Second Coming of Jesus (83.94%). These data strengthen the literature that emphasizes eschatology as a major motivation of evangelicals when it comes to Israel. However, the survey responses showed more caution (67.4% support) in the following statement, which emphasizes more direct connection between the support toward Israel and the Second Coming. In the second statement, “I support Israel because it will lead to the Second Coming of Jesus,” we saw a larger number of respondents who express rejection of the link between the two, or higher level of uncertainty.

Since pre-millennial dispensation theology expects that Jews would build a Temple for God prior to the events of the Second Coming, and eventually many Jews would convert to Christianity, we also asked respondents to respond to these statements. The results in Table A8 show that evangelicals are almost evenly divided over these statements. Since we identified the building of the Temple is an event that needs to take place in the near future, only about a half of the respondents express support for this statement. The uncertainty of the respondents regarding the question of the conversion of Jews at the Second Coming, with only about half expressing positive support, is also important to note.

Biblical narrative relates to a covenant made between God and Abraham, thus offering him and his offspring eternal blessings and turning them into chosen people. Since certain Christian readings argue that Jews lost their election by rejecting Jesus as their Messiah, we asked in the survey: “Do you believe God's covenant with the Jewish people is eternal?” The results show strong support. A total of 72.8% indicated that “yes, the covenant remains,” 5.6% said that “no, the covenant has ended,” 2.7% said that “God never had a covenant with the Jews,” and 18.9% responded with “don't know.” Similarly, the statement: “I support Israel because Jews are God's chosen people” generated high levels of agreement, with 84% responding in favor (taking into account “somewhat agree,” “agree,” and “strongly agree” responses). We can thus conclude that the majority of evangelicals do, indeed, reject supersession theology.

We asked another question regarding evangelicals' literal reading of the Bible, which taps into more recent political debates—“Do you believe the Bible says that Jerusalem is Israel's capital?”. Here again, a large majority of respondents (62%) agreed with the statement, 5.1% indicated that the “Bible does not say that Jerusalem is Israel's capital,” another 6.8% said that “Bible is not relevant in political matters,” while 26% said they do not know.

We tested several statements related to the promises God made to the Jewish people and to the Gentiles. In the responses to all statements (reported in Table A9), we saw a high level of agreement.

Since the majority of evangelicals see the Bible as the literal word of God, they express high levels of support to several statements that, although Biblical, have contemporary ramifications. Among them are that Jews are God's chosen people (84%), and that God made promises to Jews, such as giving the Land of Israel to the Jewish people (90.6%) and making Jerusalem Israel's capital (62%). According to literal reading, God also made promises to Gentiles to bless them if they would stand by Abraham and his offspring (87.7%).

The combination of “cold” eschatology and Biblical literalism, in addition to the ones mentioned earlier, has thus significantly contributed to shaping a favorable view of Jews and high support to the State of Israel by evangelical and born-again Christians.

CONCLUSION

The results of our statistical analysis show that the three strongest predictors of evangelical and born-again Christian support for Israel are (1) age (older respondents are more supportive); (2) opinion of Jews (rather than belief that Jews are God's chosen people; although both are significant predictors); and (3) socialization (frequency of hearing other evangelicals talking about Israel).

One important finding of this analysis is that there are significant differences in pro-Israel sentiment between 18 and 29 years old respondents and older evangelicals and that these differences are not driven by the fact that the younger evangelicals are less religious (in fact, we find the contrary). Younger evangelicals may be less supportive of Israel due to their ideology, which is also a statistically significant predictor of support for Israel. We find that in general young evangelicals are more likely to express centrist political positions than the older cohorts, who tend to be more conservative. Additionally, we speculate that these findings are a byproduct of different conceptions of justice, with younger evangelicals expressing a more positive attitude toward the Palestinians and more likely to perceive the Israeli policy toward the Palestinians as unjust. Certainly, this area of research merits more attention in the future. And, while we discover no statistically significant effects of race and ethnicity on Israeli support, our intuition suggests that there are some additional insights to be gained from focusing more explicitly on the study of African American evangelicals' attitudes toward Israel. Another aspect to examine in future research would be the growing trend among evangelicals toward post-tribulation premillennial dispensationalism, a belief that the rapture happens only after the great tribulation, so that evangelicals suffer with Jews.

Our research contributes to a small, but growing, literature on the opinions of a large segment of American population regarding the question of the support for Israel. The results are not just important from a political perspective of what motivates evangelicals regarding foreign policy, but also from the perspective of Jewish–Christian relations. At the aftermath of World War II, many Christian organizations understood that they needed to change their attitude toward Jews. One dramatic transformation took place, for example, with the conclusion of Vatican II (1962), in which the Roman Catholic Church took the blame from Jews for Christ's death, and made it a responsibility of all mankind. In 1993, The Holy See and the State of Israel signed an agreement that entailed mutual recognition and full diplomatic relationship. Mainline Protestant organizations also changed their attitude toward Jews, partly under the influence of Reinhold Niebuhr, a leading Protestant theologian, during the 1950s–1960s. Neibuhr accepted Judaism as a religious tradition that stands on its own, outside the confines of Christianity (Ariel Reference Ariel, Troen and Fish2017). Evangelical support for Israel and favorable view of Jews, as discussed in this paper, can be viewed as part of that transformation.

However, from the 2000s onward, some mainline Protestant organizations started changing their attitude toward Israel. In 2004, the Presbyterian Church USA adopted a resolution to divest funds from multinational corporations operating in Israel. World Council of Churches and United Church of Christ made similar pronouncements shortly after. As reported in this study, some young evangelicals are also developing a more negative outlook toward Israel. Therefore, in order to broaden the picture of American Christian attitudes toward Israel at the grassroots level, we encourage other scholars to explore similar questions to those that we have addressed in this paper by studying attitudes of mainline Protestants and Catholics toward Jews, Israel, and the Arab-Israeli conflict. While previous studies (e.g., Mayer Reference Mayer2004; Gries Reference Gries2015) made some initial inroads into this subject, this area of public opinion research is ripe for a more detailed examination.

Appendix 1

Table A1. Respondents' religiosity (Church Attendance and Bible Readership)

Table A2. Respondent's political ideology

Table A3. Opinions of Muslims and Jews: comparing 18–29 years old respondents to the older evangelicals

Table A4. Descriptive statistics for potential causes of evangelical support for Israel

Table A5. Summary statistics

Table A6. Tests of Parallel Lines Assumption

Table A7. Determinants of evangelical support for Israel (ordered logistic regression results)

Table A8. Comparing eschatological visions of pre-millennial dispensationalism

Table A9. Responses concerning God's promises to the Jews and the Gentiles

Appendix 2. Variable descriptions and coding procedures

• Support for Israel (dependent variable)—Where do you put your support? Coded 1 for “Very strong support for Palestinians”; 2 for “Support Palestinians”; 3 for “Lean toward support for Palestinians”; 4 for “Support neither”; 5 for “Lean toward support for Israel”; 6 for “Support Israel”; 7 for “Very strong support for Israel.” Coded 8 for “I do not know” and then recoded as missing value to drop from the analysis. We then recoded the original variable in the following manner: 1 for “Support Palestinians”; 2 for “Lean toward support for Palestinians”; 3 for “Support neither”; 4 for “Lean toward support for Israel”; 5 for “Support Israel.”

• Israel's existence is proof of the nearing of Jesus' Second Coming—The State of Israel is a proof of the fulfillment of prophesy regarding the nearing of Jesus' Second Coming. Coded 1 for “Strongly disagree”; 2 for “Disagree”; 3 for “Somewhat disagree”; 4 for “Neither agree nor disagree”; 5 for “Somewhat agree”; 6 for “Agree”; 7 for “Strongly agree.” Coded 8 for “Do not know” and then recoded as missing value to drop from the analysis.

• Jews are God's chosen people—I support Israel because Jews are God's chosen people. Coded 1 for “Strongly disagree”; 2 for “Disagree”; 3 for “Somewhat disagree”; 4 for “Neither agree nor disagree”; 5 for “Somewhat agree”; 6 for “Agree”; 7 for “Strongly agree.” Coded 8 for “Do not know” and then recoded as missing value to drop from the analysis.

• Israel needs to build a temple for God on the Temple Mount in the near future—Israel needs to build a temple for God on the Temple Mount in the near future. Coded 1 for “Strongly disagree”; 2 for “Disagree”; 3 for “Somewhat disagree”; 4 for “Neither agree nor disagree”; 5 for “Somewhat agree”; 6 for “Agree”; 7 for “Strongly agree.” Coded 8 for “Do not know” and then recoded as missing value to drop from the analysis.

• Cultural affinity—I support Israel because of our shared cultural and/or religious values. Coded 1 for “Strongly disagree”; 2 for “Disagree”; 3 for “Somewhat disagree”; 4 for “Neither agree nor disagree”; 5 for “Somewhat agree”; 6 for “Agree”; 7 for “Strongly agree.” Coded 8 for “Do not know” and then recoded as missing value to drop from the analysis.

• Political affinity—I support Israel because of our shared political or democratic values. Coded 1 for “Strongly disagree”; 2 for “Disagree”; 3 for “Somewhat disagree”; 4 for “Neither agree nor disagree”; 5 for “Somewhat agree”; 6 for “Agree”; 7 for “Strongly agree.” Coded 8 for “Do not know” and then recoded as missing value to drop from the analysis.

• Common geopolitical/security concerns—I support Israel because it protects the holy sites and is the only guarantor of Christian access to them. Coded 1 for “Strongly disagree”; 2 for “Disagree”; 3 for “Somewhat disagree”; 4 for “Neither agree nor disagree”; 5 for “Somewhat agree”; 6 for “Agree”; 7 for “Strongly agree.” Coded 8 for “Do not know” and then recoded as missing value to drop from the analysis.

• Guilt for previous discrimination of Jews—I support Israel because Jews suffered discrimination and extermination at the hands of Christian nations in the past. Coded 1 for “Strongly disagree”; 2 for “Disagree”; 3 for “Somewhat disagree”; 4 for “Neither agree nor disagree”; 5 for “Somewhat agree”; 6 for “Agree”; 7 for “Strongly agree.” Coded 8 for “Do not know” and then recoded as missing value to drop from the analysis.

• Evangelicals talk about Israel's importance—Estimate how often you hear evangelicals expressing the importance of supporting Israel? Coded 1 for “Never”; 2 for “Seldom”; 3 for “Once a month”; 4 for “Every week.”

• Religiosity (Church Attendance)—How frequently do you attend church or religious assemblies? Coded 1 for “Never”; 2 for “Seldom”; 3 for “A few times a year”; 4 for “Once a month”; 5 for “Two or three times a month”; 6 for “At least once a week.”

• Ideology—What best describes your political views? Coded 1 for “Extremely liberal”; 2 for “Liberal”; 3 for “Slightly liberal”; 4 for “Moderate, middle of the road”; 5 for “Slightly conservative”; 6 for “Conservative”; 7 for “Extremely conservative (7). Coded 8 for “Do not know” and then recoded as missing value to drop from the analysis.

• Opinion of Muslims—What is your opinion of Muslims? Coded 1 for “Very poor”; 2 for “Poor”; 3 for “Neutral”; 4 for “Good”; 5 for “Very good.” Coded 6 for “No opinion/Do not know” and then recoded as missing value to drop from the analysis.

• Opinion of Jews—What is your opinion of Jews as a nation/people? Coded 1 for “Very poor”; 2 for “Poor”; 3 for “Neutral”; 4 for “Good”; 5 for “Very good.” Coded 6 for “No opinion/Do not know” and then recoded as missing value to drop from the analysis.

• Age—What is your age? Coded 1 for “18–29 years old”; 2 for “30–49 years old”; 3 for “50–64 years old”; 4 for “65 years and older.”

• Gender (biological sex)—What is your biological sex at birth? Coded zero for “Male”; 1 for “Female.”

• Income—What was your total household income before taxes during the past 12 months? Coded 1 for “Less than $25,000”; 2 for “$25,000–$34,999”; 3 for “$35,000–$49,999”; 4 for “$50,000–$74,999”; 5 for “$75,000–$99,999”; 6 for “$100,000–$149,999”; 7 for “$150,000 or more.” Coded 8 for “Rather not say” and then recoded as missing value to drop from the analysis.

• Educational Attainment—What is the highest level of education you have completed? Coded 1 for “some high school”; 2 for “high school graduate”; 3 for “some college”; 4 for “trade/technical/vocational/two-year degree”; 5 for “4-year college/university degree”; 6 for “post-graduate degree.”

• Race/ethnicity—What is your race/ethnicity? Coded 1 for “American Indian or Alaskan Native”; 2 for “Asian”; 3 for “Black or African American”; 4 for “Hispanic or Latino”; 5 for “Multiracial”; 6 for “Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander”; 7 for “Other”; 8 for “White, non-Hispanic.” Additionally, dummy variables for each of the value categories were created, where 1 represented a particular race/ethnicity and zero otherwise.

• Marital Status—What is your current marital status? Coded 1 for Single/Never married; 2 for “Separated”; 3 for “Divorced”; 4 for “Widowed”; 5 for “Married.” Coded 6 for “Rather not say” and then recoded as missing value to drop from the analysis.

• Region of Residence—Which U.S. region are you from? Coded 1 for “Midwest—IA, IL, IN, KS, MI, MN, MO, ND, NE, OH, SD, WI”; 2 for “Northeast—CT, DC, DE, MA, MD, ME, NH, NJ, NY, PA, RI, VT”; 3 for “Southeast—AL, AR, FL, GA, KY, LA, MS, NC, SC, TN, VA, WV”; 4 for “Southwest—AZ, NM, OK, TX”; 5 for “West—AK, CA, CO, HI, ID, MT, NV, OR, UT, WA, WY.” Respondents were presented the name of the region and the abbreviations for the specific states to aid in their selection. We also generated five dichotomous variables (one for each region), where 1 reflects a particular region and the rest of the regions are coded as zero.

• Area of residence (rural, suburban, urban)—Which of the following best describes the area you live in? Coded 1 for “Urban”; 2 for “Suburban”; 3 for “Rural.” We also generated three dichotomous variables (one for each area of residence), where 1 reflects a particular area of residence and the rest are coded as zero.

• Bible Readership—How often do you read the Bible? Coded 1 for “Never”; 2 for “Seldom”; 3 for “Once or twice a month”; 4 for “Only in church”; 5 for “Once a week”; 6 for “At least twice a week”; 7 for “Every day.”