INTRODUCTION

This article seeks to establish the key factors accounting for the expansion of Boko Haram insurgence in the Lake Chad region. Boko Haram's evolution and expansion beyond Maiduguri (Borno State, Nigeria) have been explained from a number of perspectives. Religious and poverty trajectories form the dominant arguments in the literature, while the natural resources nexus to insurgency has been underexplored. The original discourse among economists about a “resource curse” was whether resource dependence impacts negatively on the growth of a country's GDP, leading to a negative correlation between economic and political improvements in countries endowed with natural resources when compared to those with less natural resources (Collier and Hoeffler Reference Collier and Hoeffler2004; Ross Reference Ross2012; Morrison Reference Morrison2013; de Soysa Reference de Soysa2015). The debate has been extended to terrorism in view of some low- and middle-income, oil-exporting countries slipping into political violence (Ross Reference Ross2012), and the influence of oil as one of the causes of the 9/11 attacks (Wenar Reference Wenar2016, xxvi). This study is interested in the oil politics in the Lake Chad region and its connection to the Boko Haram organization and one of its splinter groups namely the Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP). Richard Murphy'sFootnote 1 question, “What if oil is the true ideology of Boko Haram?” draws attention to the vast natural resources, particularly oil and gas, in the Lake Chad region and the contestations among riparian states. Also, Ibrahim ShettimaFootnote 2 raised an alarm that Cameroon is extracting about 200,000 barrels of oil per day on the Nigerian border, so you might not even rule out an international conspiracy against Nigeria in the quest for oil in the Lake Chad region. These are pointers that require academic attention beyond the dominant narratives of religion and poverty in the terrorism literature.

Religion has been hypothesized as a strong identity cleavage that drives most conflicts (Reynal-Querol Reference Reynal-Querol2002; Rapoport Reference Rapoport, Cronin and Ludes2004; Hoffman Reference Hoffman2006). It is a popular theme in the discussion of terrorism. Religiously motivated terrorists and terrorist organizations are common, because religion is used to facilitate recruitment as well as indoctrination of volunteers for suicide missions. Religiously Motivated Terrorist Groups (RMTGs) are more violent than non-religious groups, since their idea of society stems from a divine motivation of religion, long-term view of religious goals, and the indivisibility of religion and politics or society (Juergensmeyer Reference Juergensmeyer2003; Hoffman Reference Hoffman2006; Asal and Rethemeyer Reference Asal and Rethemeyer2008). In most Islamic countries, where the doctrines of Wahhabism, Salafism, the non-violent Izala movement, and other fundamentalist sects are dominant, the central assumption is that everything necessary to ordering society is contained in the sacred texts of religion. The common Salafi rhetoric is: the Qur'ran is my constitution (Hoffman Reference Hoffman1995; Ranstorp Reference Ranstorp1996; Rapoport Reference Rapoport, Cronin and Ludes2004; Benard Reference Benard2005; McGovern Reference McGovern and Smith2010; Asfura-Heim and MacQuaid Reference Asfura-Heim and McQuaid2015; Thurston Reference Thurston2016; Omenma and Hendricks Reference Omenma and Hendricks2018). Boko Haram shares some characteristics of religious terrorism: it is inclined to Salafist ideology, religious exclusivism that opposes all other value systems, rival interpretations of Islam, pledge of allegiance to the Islamic State, and aims to Islamize Nigeria. An exclusively religion-based account of Boko Haram based on the above shared characteristics will, no doubt, foreclose a more critical beneath-the-surface aim and ideology of Boko Haram.

Despite the evidence of increased religious terrorism, not everyone has bought into the religion thesis. Hoffman (Reference Hoffman1993), Ranstorp (Reference Ranstorp1996), and Laqueur (Reference Laqueur1999) have questioned the religious terrorism perceptions, because “religion functions as a legitimizing force” (Hoffman Reference Hoffman1993, 12), and its content is “only secondary to ‘burning passion’, which serves as the primary driving force behind terrorist activity” (Laqueur Reference Laqueur1999, 230). The resort to holy rhetoric by terrorist organizations serves primarily as a bonding and morale boosting tool rather than as a common explanation for acts of terrorism (Dolnik and Gunaratna Reference Dolnik, Gunaratna and Haynes2009, 345). Distinction between religion as a motivating factor and other factors such as politics, economics, or grievances is blurred in the case of Islamic fundamentalism. Abubakar Shekau, the spiritual leader of Boko Haram, uses Islamic rhetoric, such as to “Fight the infidels … and take their souls in order to purify the land”, or the threat of Islamization of northern Nigeria (Human Rights Watch 2016; Olojo Reference Olojo2018). But this rhetoric serves primarily as a bonding and moral boosting tool rather than being the primary motivation for Boko Haram activities.

The natural resource dimension is one of the important discussions that has not been tapped into, or is kept at bay when it comes to understanding the motivations of contemporary terrorism. Collier and Hoeffler (Reference Collier and Hoeffler2004) argue that many rebellions appear to be linked to the capture of resources, which offers rebellious groups opportunities for predation (controlling primary commodity production and exports). However, Collier and Hoeffler (Reference Collier and Hoeffler2000; Reference Collier and Hoeffler2004) focus on war-torn countries with large deposits of oil, diamonds, gemstones, and other mineral resources such as Afghanistan, Angola, Burma, Cambodia, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Liberia, and Sierra Leone to support their argument. Given the enormous agricultural resources in the Lake Chad areas, the estimated deposits of 2.32 billion barrels of oil reserves and 14.65 trillion cubic feet of natural gas in the Lake region as well as Krueger's (Reference Krueger2007, 46) assertion that “terrorists themselves do not tend to highlight economic factors in their own rhetoric”, it becomes imperative for a more critical enquiry on the possible link between Boko Haram activities and natural resources.

Attacks on energy facilities by terrorist organizations have a long history, which are seen as a strategy of bargaining and even as a source of income. Koknar (Reference Koknar, Luft and Anne2009) identifies two types of terrorist groups that attack the energy sector. The first group is non-state actors, who are politically motivated terrorist groups, where criminals act in collaboration with the terrorists. The second group is state-sponsored terrorist groups that operate at the behest of a state actor. Both types of terrorist organizations have common aims of causing monumental destruction to a nation's economy; and the intent to spread anxiety among citizens by creating the impression that every critical infrastructure is vulnerable to attack. When two or more states sit astride a large underground oil basin, there is always the tendency of using non-state armed groups as a tool of statecraft. The Nigerian government had often been suspicious of Chad and Niger's close relations with a particular faction of Boko Haram and “criticized Cameroon for not doing enough to fight the spread of violent extremism in its territory” (Comolli Reference Comolli2015, 89). This leads to two assumptions: first, the possible pursuit of economic rather than religious interest by Boko Haram insurgent groups, and second, the likely use of Boko Haram against Nigerian economic benefits in the Lake Chad region.

In this paper, I adopt a qualitative research analysis of recorded events. My data sources are the Global Terrorism Index (GTI), International Crisis Group (ICG), Lake Chad Basin Commission (LCBC), and research literature dealing with energy security. I structured the paper into four sections. The first section provides an overview of the debate on the motivation for terrorism and background information on Lake Chad. The second section reviews theoretical literature on natural resources and the link to conflict. The third section deals with the description of the Lake Chad basin—its geography, climatic features, the natural resources found within and around the lake, and conflicts associated with the Lake. The fourth section provides specific examples of state dispositions toward Boko Haram activities. The article concludes that economic interest around Lake Chad oil and gas resources are possible factors that take primacy over religious motivations of the terrorist groups.

Strategic Interest and Energy Demands in the Lake Chad

The energy dimension of the ongoing insurgency in the Lake Chad area needs considerable attention, because most of the riparian states are presently dependent on oil revenue from the region. Chad and Niger have a spread of oilfields in their countries, while there is the prediction that “Cameroon could become an important player in commercial natural gas by 2018” (Brown Reference Brown2013, 124). Major importing countries place a premium on oil from exporting regions that are easily accessible for the purpose of reducing the transport time and cost and improving supply security. The Lake Chad region falls within this world energy strategy for three important considerations. First, the energy demand for African hydrocarbons has become so intense and with the traditional producers like Algeria and Nigeria where poor government programs have been discouraging, Western oil producers expanding their investments, other places like Lake Chad, Burkina Faso, Ghana, Lesotho, and even Somalia have experienced an exploration boom. Also, Total (the largest petroleum company in France) started focusing on Angola and Nigeria since it is reported that oil reserves in Cameroon, the Republic of the Congo, and Gabon are drying up (Ismail and Sköns Reference Ismail and Sköns2014, 45).

Secondly, relationships between Nigeria and her Francophone neighboring countries have been historically unfriendly due to contestations over the ownership and use of the Lake resources. The relative stability of oil-producing communities in Cameroon, Niger, and Chad compared to the rebellious character of the Niger Delta in Nigeria makes energy sources from Nigerian neighbors less risky to access. Thirdly, the instant economic boom associated with oil wealth is a source of concern. For instance, Chad has an estimated production of 300,000 barrels of oil from Doba; Cameroon earns about $20.40 million from the pipeline royalties, and the windfall from Zender and Agadem oil extraction sustains the economy of Niger (Mitchell, Marcel and Mitchell Reference Mitchell, Marcel and Mitchell2012, 2; Brown Reference Brown2013, 199; Lin Reference Lin2013, 33). These have steadily increased the risk factors in the Lake Chad region, and are some of the possible considerations for Boko Haram insurrections in the Lake Chad region.

Among the four countries that share physical boundaries with the Lake, Chad is most dependent on the Lake, with its capital and demographic center located close to the Lake. Despite Chad's proximity, the Lake “has largely stayed off the radar of successive regimes” in Chad, but “the growth in oil revenues from 2007 onwards brought” about the Lake's strategic importance to the Chadian government (International Crisis Group (ICG) 2017, 7). Also, fish farmers from Nigeria populate a key portion of the Lake, but in terms of economic importance to Nigeria, the Niger Delta comes first on the list of economic priorities, before the Lake Chad basin (Galeazzi et al. Reference Galeazzi, Medinilla, Ebiede and Desmidt2017, 4). For the Nigerien government, and even more so in Cameroon, the Lake was regarded as a remote border area with less appeal to the national governments (ICG 2017, 6). For the past few decades, the Lake had a marginal geopolitical interest for the riparian states until geologists identified oil reserves beneath the Lake bed (Jane's Intelligent Watch 2005). The geological survey estimates Lake Chad oil reserves at 232 billion barrels and 14 65 trillion cubic feet of natural gas (US Geological Survey (USGS) 2010). National interests began to converge as soon as oil and gas firms started exploring the possibility of extracting oil minerals from the Lake Chad basin. Precisely, the construction of oil drilling fields in the year 2000 in Doba, Chad; the building of a 1,000 km pipeline from Chad to the maritime port off the coast of Cameroon, and the Nigerien Agadem oilfield in the year 2011 becoming the turning points (ICG 2009, 3; Brown Reference Brown2013). In contrast, oil extraction from the Nigerian side of the Lake has been unrealistic for reasons such as the initial lack of interest by the Nigerian government, and to the current insurgency activities in the northeast.

The Lake's (other) valuable resources—water, grasses, fish, grains, and other raw materials—have made the region not only economically attractive, but provide safe havens for criminals. In other words, while the Lake's resources have been of tremendous economic value for the inhabitants on the one hand, the vegetation, mangroves, and the adjoining forest provide safe havens for criminals, on the other hand. Most terrorist groups conduct some form of implicit cost-benefit analysis. They need a support base that provides needed material, such as money, safe houses, and recruits. They also require a hospitable environment to survive. Boko Haram's stronghold in Lake Chad and Sambisa forest is perceived as a better chance of reaching their objectives.

Natural Resources and the Conflict Debate

There is a large body of literature that discusses the causes of conflicts. Religion discourses are the dominant ideological linkage to terrorism (Christmann Reference Christmann2012; Comolli Reference Comolli2015; Mercy Corps 2016; Connor Reference Connor2017). The attraction to fight against “un-Islamic” elements, which most terrorist groups profess, makes them appear primarily as religious groups seeking to render a “pure” religious society. Krueger (Reference Krueger2007, 48) argues that “terrorists are not people who have nothing to live for. On the contrary, they are people who believe in something so strongly that they are willing to die for it”. Hoffman (Reference Hoffman2006, 82) posits that religion was an inseparable component of many terrorist organizations in the past, but presently, the dominant motivation for their actions is political rather than religious. These threads of arguments help to illuminate the fact that terrorism may be motivated by other factors than religion alone.

There are multiple problems associated with defining religious extremism as a justification for terrorism. One such problem is the probability of overgeneralization in the analysis of the relationship between religious extremism and terrorism. Stepanova (Reference Stepanova2008, 61) cautions that extreme care should be taken because of the specific features of terrorism inspired by different versions of religious extremism—ethno-confessional or quasi-religious. For instance, terrorist organizations are normally inspired or formally blessed by some spiritual authorities or guides. The blessing or legal pronouncement (fatwa) from spiritual leaders legitimizes the use of terrorist means. Such spiritual leaders are expected to be involved in the organization of the group by occupying a senior or leadership position (Lakhdar Reference Lakhdar2002). It is not enough to have an Islamic cleric in the extremist group, but there has to be a “consistent use of religious rituals or sacred texts for the inspiration and justification of violence, including terrorism, and for activities such as attracting and recruiting new members” (Stepanova Reference Stepanova2008, 61). Also, religious terrorist organizations rely on holy texts, which are associated with groups driven by strong religious convictions and who are likely to use and justify armed violence. Strangely, so many quasi-religious groups use different extracts from the same holy texts to justify their activities, but this does not necessarily define such group as driven by Islam. In addition, terrorist organizations equally go beyond the use of sacred texts to employ religious cults, such as self-sacrifice, and the cult of martyrdom, thereby seeing terrorist attacks as acts of faith. Finally, extremist groups, which are motivated by religion, interpret and identify “the enemy” in much broader terms, almost in a universal way, more so than the ethno-confessional or quasi-religious groups that do not emphasize the global appeal against enemies. It is the combination of all these features that helps to differentiate between terrorist groups for whom religion is nothing more than an essential part of their ethno-confessional background on the one hand and genuinely religious extremist groups on the other hand. Boko Haram characteristics do not meet most of these features except the use of suicide bombers, but their suicide bombers are either induced or motivated by the cash benefits.

Related to this are the economic conditions as a factor motivating terrorism groups. Poor economic situations are defined as limited access to basic life needs, which may intensify grievances and provide a more supportive environment for terrorist groups (Mousseau Reference Mousseau2002/03; Jones and Libicki Reference Jones and Libicki2008). Grievances are difficult to measure independent of terrorism, but measures of average levels of discrimination are feasible. Some argue that greater economic inequality creates broad alienations and grievances that favor terrorism. Samuel Huntington (Reference Huntington2001, 48) once warned that “Governments that fail to meet the basic welfare and economic needs of their peoples and suppress their liberties, generate violent opposition to themselves and to Western governments that support them”. The economic condition argument appears valid given the high rate of illiteracy, poverty, long years of government neglect, and poor access to basic food needs among the majority of communities in the northeast of Nigeria. But the poverty argument was debunked by the late Mohammed Yusuf, the founder of Boko Haram, that “the present Western-style education is mixed with issues that run contrary to our beliefs in Islam…Everybody is living according to his means” (Comolli Reference Comolli2015, 48, 57). Fighting against unjust economic conditions is, therefore, not the primary motivating factor as far as the Boko Haram founder is concerned. Colgan states that “petrostates are among the most violent states in the world”, though not all petrostates have a propensity for aggression, but oil- and gas-producing countries are “targets of attack 30% more frequently than non-petrostates” (Colgan Reference Colgan2013).

Recent studies have linked environmental factors to conflicts. Thomas Malthus's theories on eco-scarcity and population pressure argue that poor people will “impoverish” the soil and natural resources by overuse (Cohen Reference Cohen1995; Blaikie Reference Blaikie, Braun and Castree2001, 134–5; Buseth Reference Buseth2009, 10), and the likely effects are conflicts or wars over access to food, water, and energy scarcity (Schwartz and Randall Reference Schwartz and Randall2003, 15, 17). This has been expanded by Meadows et al. (Reference Meadows, Meadows, Randers and Behrens.1972), Hardin (Reference Hardin1968), Mehta (Reference Mehta2007), and Gore (Reference Gore2007) to a more specific environmental concern. Meadows et al. (Reference Meadows, Meadows, Randers and Behrens.1972) discuss the consequences of a rapidly growing population against shrinking resources, while Hardin (Reference Hardin1968) talks of the continuous grazing of animals without any form of a control system, where the outcome will be overuse and degradation of resources. More so, the Toronto Group, as well as the Swiss Peace Foundation, focused on how environmental changes and stress can lead to conflict (Homer-Dixon Reference Homer-Dixon1991; Reference Homer-Dixon1994; Reference Homer-Dixon1995; Reference Homer-Dixon1999; Baechler Reference Baechler1999; Klare Reference Klare2006; Gore Reference Gore2007). This link is found on the notion that climate change will have a negative effect on natural resources, thereby making natural resources scarce, and competition over them harder and eventually conflictual. There may be indirect linkages between climate change and the risk of conflict. That is, factors that play a role in increasing conflict risk may be reinforced by climate change. Local conflicts around natural resources may be triggered or exacerbated by climate-related factors, particularly in economies that are highly dependent on natural resources. Opara et al. (Reference Opara, Stringer, Dougill and Bila2015, 2) note that the rate of climate change in the Lake Chad region has been “unprecedented”, resulting in resource scarcity and the subsequent cases of conflict in the Lake region. It is imperative to realize how and under what settings these changes may lead to violent conflict. While it may be valid to associate climate change with the competition for and clashes over drinking water, livestock (grazing fields), fishing ponds, and agricultural land, it may be difficult to accept scarcity of natural resources as the possible driver of terrorism in the Lake Chad basin.

Collier and Hoeffler's (Reference Collier and Hoeffler2000) influential studies on “greed and grievance” represent the first systematic analysis of conflict found on strong empirical support that natural resources motivate rapacious behavior, thereby leading to violent conflicts or wars. They postulate that natural resources do not only constitute challenges to the economy of a state, but “primary commodity exports substantially increase conflict risk” (Collier and Hoeffler Reference Collier and Hoeffler2004, 588). They analyzed 73 civil conflicts that occurred between 1965 and 1999 and concluded that the most powerful explanatory factor for these conflicts was the fact that they occurred in states that derived a significant amount of their GDP from the export of primary commodities. Hoeffler (Reference Hoeffler2012) presents some basic principles to support the resource curse argument. First, rebels may be inspired by the prospects of private gain that organized violence can offer. Second, rebels are motivated by a leader who focuses on the common interests—religion, ethnicity, or class that addresses grievances. Third, rebellions start with a small group of people that require finance to hold them together (Hoeffler Reference Hoeffler2012, 3–4). He concludes that common interests as well as private gain are a possible motivation for conflicts. Hoeffler draws some of his inferences from Weinstein's thesis that “the absence of economic endowments makes recruitment more difficult”, which suggests that opportunities for large profits attract more recruitment to violent groups (Weinstein Reference Weinstein2005, 599). In support of the economic incentives argument, Jenne, Saideman and Lowe's (Reference Jenne, Saideman and Lowe2007, 524) study shows that external military support by organizations or interest groups makes a violent campaign against the government more likely when there is evidence of large deposits of natural resources. The theory as discussed by Collier and Hoeffler is related to both greed and funds needed for an organization of non-state security actors to flourish. To run an active military organization of armed conflict, more human and financial resources are needed.

Explaining why countries wage war, Clausewitz (Reference Clausewitz1976, 87), Klare (Reference Klare2001, 31), and Smith (Reference Smith2003, 219) argue that states engage in war to secure resources, but such resources must be vital to the national interest. In a conflict over natural resources, what is considered as the state's national security is intricately tied to natural resources. In other words, if the resources are not threatening national security, such resources will attract less conflict, but when considered as important to national security, most nations will not “surrender vital national interests” (Klare Reference Klare2001, 23). It is the national interest or security that determines state reaction—to deploy military forces or support non-state actors in a conflict. States use terrorism to substitute traditional warfare if the latter is too expensive or risky. Where traditional forms of warfare are considered overtly costly or would result in uncertain outcomes, terrorism may be regarded as an appropriate substitute. This may result in state provision of a range of support mechanisms, including propaganda, financial aid, training, intelligence, weapons, and even direct involvement (Terry Reference Terry1986, 161; Byman Reference Byman2005, 22). Värk (Reference Värk.2011, 82) notes that it has “become a rewarding alternative approach of foreign policy to use this extraordinary, but potentially effective means, as it avoids or minimizes the risk of taking responsibility”. Since it is rather easy to hide relations with non-state actors, the use of terrorism constitutes low risks but can also be an influential and cheap “foreign policy”. The most important reason for the tendency to use terrorism as a state's proxy war, according to Byman, is likely for strategic interest—to influence its neighbors or achieve other aims of states. Is this scenario applicable to the Lake Chad region, where a possible state cooperation or acquiescence with Boko Haram gives the state improved access to the oil resources or, the probability of Boko Haram abandoning the religious ideological motivation to a more lucrative economic interest? Relying on the principles of state “strategic goal” or “natural resource interest” on one hand, and the calculation that a terrorist group requires a hospitable environment to survive on the other hand, I examine the possibility of economic benefits of terrorist groups to draw conclusions. In general, research on the economic linkage to terrorism currently constitutes a small portion of the literature, and it is my hope that this study will encourage more research on the relationship between economic interests and the growth of terrorism in Africa.

Lake Chad Resources and the Strategic Interests among Nations

Lake Chad is a freshwater lake located in Central Africa. It is a shallow lake with a mean depth of 4 m (FAO/LCBC 2011, 32). The Lake is surrounded by different types of ecological zones: deserts, forests, wetlands, savannahs, and mountains (Ovie and Belal Reference Ovie, Belal, De Young, Sheridan, Davies and Hjort2011). The Lake water is supplied by the Chari-Logone River (in the Central African Republic), the Komadugu-Yobe River (in Nigeria), and the Yedsara/Ngadda River (in Cameroon) (UNEP GIWA Reference Fortnam and Oguntula2004). It provides a vital source of water to more than 30 million people living in the Lake areas and forms the bedrock of several economic activities, particularly fishing, agriculture, hunting, and pastoralism (LCBC 2016, 3). The basin, where Lake Chad is found, covers an area of 2,397,424 km2, or 8% of the African continent, and is surrounded by transboundary basins such as the Nile basin to the east, the Congo basin to the south, the Niger basin to the west, and the Nubian basin to the north (LCBC 2016, 31).

The surface area of the Lake is 12,177 km2 as at 2012, and the average depth is between 1.5 and 4 m (LCBC 2016, 29). The Lake surface traverses four countries—Cameroon, Chad, Niger, and Nigeria. Its climate composition is arid north of the basin and semi-arid in the south. Over the last 50 years, the Lake has decreased in size from an area of 25,000 km2 to its present size of 4,516 km2 with a maximum depth of 11 m (see Figure 1) due to drought. Appendix 1 shows the cartography of the different Lake sizes over various periods.

Figure 1. The sizes of the lake for the last 50 years. Area of 25,000 km2. Source: LCBC, 2016, 29.

The Global International Waters Assessment (GIWA) project estimates the population of people living in the basin at 37 million (2004, 29). Sixty percent of the population earn their livelihoods from the natural water resources—livestock, agriculture, and fishing (GIWA Reference Fortnam and Oguntula2004, 30). Chad is most economically dependent on the basin's resources with 91% of the Chadian population living in the basin. Nigerians represent the largest national population group in the basin, with over 26 million people. Cameroon and Niger have equally high populations living in the lakeside region and have an average of 20% of their respective national populations living within the basin (LCBC 2016, 66).

The economic activities within the Lake region are predominantly fishing, agriculture, and stock farming. Fishing constitutes the mainstay of the local economy, and there are respectively between 120 and 140 species of fish in Lake Chad and its tributaries (LCBC 2016, 53). In 2012, the estimated fish production of the Lake was set at about 100,000 tonnes, with a value of around US$220 million (LCBC 2016, 104). Nigeria is particularly dominant in the fishing economy (38%), followed by Niger (32%), Cameroon (21%), and Chad (9%) (LCBC 2016, 104). In agriculture, food crops such as millet, sorghum, wheat, cocoyam, taro, maize, cassava, sweet potato, yam, onion, bell pepper, and okra and cash crops such as cotton, peanuts, rice, and dates are the key components. The quantity of wheat, maize, millet, paddy, sorghum, and peanuts produced in the Lake district by Cameroon, Chad, Niger, and Nigeria stood at 41,396,589 tonnes in 2012 (LCBC 2016, 92). Cotton, also, is a source of income produced in the north of Cameroon, the south of Chad, in Nigeria and, to a lesser extent, in Niger. Cameroon, which produces US$130 million worth of cotton, and Chad, which produces US$41 million, are among the world's top 30 cotton-exporting countries (LCBC 2016, 96). Livestock is as productive a sector as crop growing in the basin. The rangelands typically hold large and small livestock such as breeds of cattle, horse, camel, donkey, goat, sheep, poultry, and pig. Headcounts of livestock—cattle, goat, sheep, and camel—produced by the countries bordering the Lake stood at 184,033,539 animals in 2012 (LCBC 2016, 98). The herds constitute an important form of capital, producing meat, milk, leather, etc., and in the Republic of Niger, the sales of stock farming produce are second only to uranium.

Apart from water resources, oil and gas are other components found in the Lake region. The United States Geological Survey (USGS) (2010) had estimated mean volumes of 232 billion barrels of oil, 14.65 trillion cubic feet of natural gas, and 391 million barrels of natural gas liquids in the Chad basin. As at 2010, the province contained eight oilfields—three in Chad and five in Niger—and is considered to be underexplored for its size (USGS 2010). Chad's major oilfields in Doba are estimated to contain reserves of 900 million barrels (Lin Reference Lin2013, 33). Chad's oil production peaked at 126,200 barrels per day in 2010 (Pilling Reference Pilling2013) and averaged 115,000 barrels per day in 2011. The Republic of Niger has discovered three distinct areas of oil and gas potential in the Lake Chad part of their country at the Agadem oilfield. It covers the southern half of the Termit-Tenere Rift, bordering Chad to the east. The Niger government estimates the proven oil reserves in Agadem at 324 million barrels but has also reported that oil reserves could prove to be three times higher than this number (Brown Reference Brown2013, 200). The Agadem oilfield started its operations in 2011, and to ensure easy exportation, the Niger government signed an agreement with Chad in July 2012 to construct a 600 km pipeline linked to the Chad–Cameroon pipeline (Brown Reference Brown2013, 199). The projection was to begin producing oil at four fields in its Agadem block by early 2014, with production increasing to 80,000 barrels per day, 20,000 of which would be processed at the refinery near Zinder and 60,000 barrels per day exported through the pipeline (Petroleum Africa, 3 July 2012). Since 2003, Chad and Cameroon have been exporting oil from the Doba crude oilfields in southern Chad via a 1,000 km pipeline through neighboring Cameroon to the port of Kribi, on the Gulf of Guinea. Eighty-five percent of this pipeline is located in Cameroon (Mitchell, Marcel and Mitchell Reference Mitchell, Marcel and Mitchell2012, 2).

The riparian countries, except Nigeria, are extracting oil in the Lake Chad part of their countries. Nigeria entered into a partnership with the Chinese National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) in 2009 to locate the possible areas where there are sufficient hydrocarbons in the Nigerian portion (Kukawa, Borno State) of the Lake Chad basin. The initial results from the 3D exploration “generated about 420 seismic data” (Vanguard (Nigeria) newspaper, November 29, 2010), and an estimate of $20 billion was an expected yearly income from the Lake's oil (Vanguard (Nigeria) newspaper, November 9, 2015). Nigeria's exploration of oil from the Basin, which extends through Yobe, Borno, and Adamawa States, has been hindered by many factors, among them is the Boko Haram insurgency, whose deliberate activities are possibly working against economic benefits of Nigeria. Oil has been discovered in Lake Chad, but terrorism continues to push forward the mission of Nigeria to start drilling for commercial quantities. Incidentally, Boko Haram, which was formed as a non-violent religious group in the early 2000s, started its violent campaign in 2009 in the Maiduguri city of Nigeria, but expanded to the Lake Chad region in 2014, thereby challenging the Nigerian authority's control of the natural resources in the Lake areas.

The Lake's Natural Resources and Conflicts among Nations

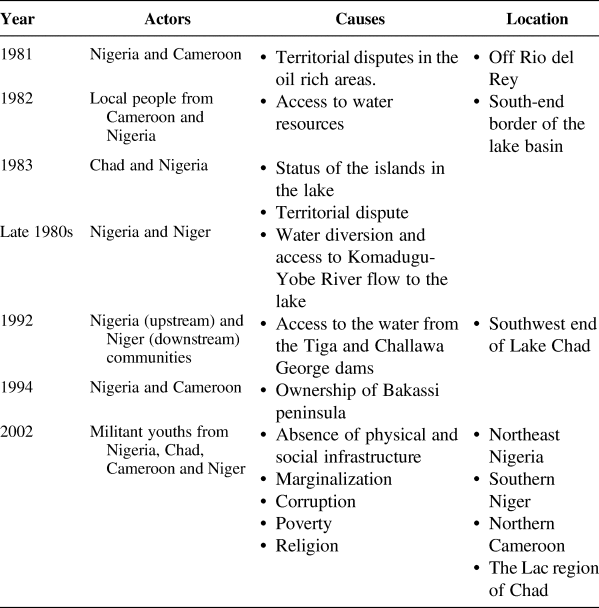

Before the emergence of Boko Haram, there were repeated cases of armed conflicts on the Lake borders between nations, and among ethnic groups. The region was known for organized crime, banditry, and other armed groups who took advantage of the lack of state presence to establish sanctuaries in the Lake. Most of the conflicts were based on access to and use of water resources, fishing rights, and grazing land. For instance, the border conflicts between Cameroon and Nigeria, Chad and Nigeria, and on the northern border, between the Central African Republic and Chad are linked to the natural resources found in the Lake territory. Sometimes the conflict is internal to the nation, resulting in internal displacement and local economic adjustments, and other times, it is between groups of different nationalities using the Lake as a means of livelihood. For example, as early as 1964, guerrillas from the Sawaba liberation movement briefly seized Bosso in Niger (Pérouse de Montclos, Reference Pérouse de Montclos2015). In 1978, the Lake also served as a refuge for the “Third Liberation Army” of the National Liberation Front of Chad (FROLINAT). A few years later, the Popular Movement for the Liberation of Chad (MPLT) set up rear bases on the Nigerian side of the area and recruited fighters around the Lake and in Kanem. In 1990, with the fall of the Hissène Habré dictatorship, the former president's supporters also regrouped in the area under the Movement for the Defence of Democracy (MDD). The Lake has since served as a safe haven for Tubu rebels, Chadian army deserters, and smugglers of all kinds. Various rebellions took advantage of the outlying position of regions far from the control of government forces (Magrin and Pérouse de Montclos Reference Magrin and Pérouse de Montclos2018, 99). Lake Chad area, due to the porous nature of national boundaries, has provided a suitable environment for non-state armed groups who used it as a base to challenge state authorities. Table 1 shows some major conflicts in the Lake Chad region from 1982 to 2002.

Table 1. Some major conflicts in Lake Chad, 1980–2002

Sources: Opara et al. Reference Opara, Stringer, Dougill and Bila2015, 315–316; Hill, Reference Hill (Major)2009, 34; Omenma and Hendricks, Reference Omenma and Hendricks2018, 8.

What is significant of and common in these conflicts is the centrality of water resources—fishing space, agricultural land, grazing land, river flow, and ownership status of the portion of the Lake. Also, the period witnessed occasional militarized conflicts that involved state actors, particularly Nigeria versus Chad, Nigeria and Niger, and the Cameroonian and Nigerian army clashes. None of these conflicts had been traced to religious motives. Religious terrorists seek to use violence to further what they see as divinely commanded purposes, often targeting broad categories of foes in an attempt to bring about sweeping faith-based change.

Boko Haram's motive remains a matter of debate, but it is obvious that it has transformed from a non-violent religious group in 2002 to a group who launches aggressive, violent campaigns. Three dominant motives are commonly cited in the literature. Firstly, Boko Haram is a faith-based Islamic group that rejects Western education while advocating Islamic sharia law. Secondly, the group has a political motive, particularly when it is considered as a tool to win power and control government patronage. Thirdly, there is the poverty theory that considers Boko Haram as a movement of grassroots anger over marginalization, deprivation, and poverty in the north. These different perspectives make it difficult for scholars to “pin the organization down and define its motives” (Walker Reference Walker2012, 8). But, as the availability of economic benefits of controlling resources increases, so also will the overall capability of the group rise, thereby providing greater ability for the escalation of violence. With Boko Haram's devastating attack on the Nigerian oil exploration team and the group's imposition of taxes on products (smoked fish, red peppers, onions, cotton, grains, etc.) circulating in the Lake areas under its control, it appears that economic incentives are becoming a dominant factor.

Boko Haram: the Proxy Conflicts in the Lake Chad Basin

Energy resources, such as oil and gas, pose a high risk of conflict, particularly when the “key sources or deposits of these materials are shared by two or more nations, or lie in contested border areas or offshore economic zones” (Klare Reference Klare2001, 21). The viability of conflict is shaped by many factors. de Soysa (Reference de Soysa2015) argues that beside the influence of religion and economic challenges, the size and nature of the payoffs for investing in violence as well as other potentially “profitable” enterprises also play a role. Conflict is most likely to occur when two or more states sit astride a large underground oil basin, because underground resource extraction can go beyond one's territory under international “Rule of Capture”. Lake Chad oil is an underground oil basin located in Doba, southern Chad, and Diffa in Niger, which shares a common border with Damasak, Nigeria. Abba Aji Kalli, the Borno State coordinator of the Civilian Joint Task Force (Civilian-JTF), reveals that religion may not be driving the Boko Haram insurgency anymore, rather, the oil factor is adding a new dimension to the group activities.

The oil we have in Borno State, is more than the Niger Delta oil, because, Borno from Gijigana that reached Baga, up to Marita to the Lake Chad, we have enough oil. And, Borno is at a lower level. And, we have Libya, Niger, Chad and Cameroon at the upper level. If Borno State oil has started production because they have one link, one road, things will be bad to our neighbouring countries (Abba Reference Abba2017, interview).

Alhaji Kashim Shettima, Governor of Borno state, corroborated this claim and urges the Nigerian government to pursue the exploring of oil and gas in the Lake Chad region with a sense of national urgency and vigor. He notes:

The oil that Niger Republic exploits is found in the Diffa region. The Diffa is eighteen kilometres from Damasak, sharing this contiguous border, the same people, the land, the same topography. Cameroon is extracting 200,000 barrels of oil per day from the Nigerian border, so, you might not even rule out international fabrications to our quest for oil in the Lake Chad region (Channels Television (Nigeria) October 29, 2017).

Analysts, like Richard Murphy, have argued that the attack on the Nigerian oil exploration team in the Lake Chad basin could not have been by happenstance, considering the precision of the attack and sophisticated war weapons used to execute the attack (Murphy Reference Murphy2017). The attack was attributed to the Abu Mus'ab al-Barnawi faction of Islamic State-supported Boko Haram (The Guardian (Nigeria) newspaper, July 29, 2017b). The al-Barnawi faction, known as the ISWAP, controls northern Borno, and a large part of the Lake Chad region, and this faction “is hiding in Chad, where Boko Haram defections peaked in 2017” (Connor Reference Connor2017, 12; The Guardian (Nigeria) newspaper, March 30, 2017a). The open announcement by the Chadian President, Idriss Deby, that Boko Haram leader, Abubakar Shekau, has been replaced by Mahamat Daoud, shows President Deby's “closeness to them and the external links” of Boko Haram to the Chadian government (Ebute Reference Ebute2017). The implications for the alleged romance between the al-Barnawi Boko Haram faction and Chadian government may be Chad's tacit retaliation for the support the Nigerian government gave the “third army” (or “Forces armées occidentales”), a dissident FROLINAT that caused political upheaval in Chad in 1978. The conflict between Nigeria and Chad has a history dating back to 1978, and the discovery of oil and gas in large quantities has merely renewed the diplomatic tensions. Also, Richard Murphy considers the safe haven granted to the al-Barnawi faction as a possible proxy war by Chad to disrupt Nigerian efforts to explore the Lake's oil and gas resources. The topography of the area, the crude oil deposits toward Nigerian territory, and Nigeria exploring these deposits will limit Chad's oil exploration.

Chad started oil exportation from the Doba field in 2003, and as of 2010, it became Africa's 10th largest oil producer (Brown Reference Brown2013, 22). The country's national budget has skyrocketed from a modest “$670 million to more than $2.8 billion between 2004 and 2014” (ICG 2016a, 14). Furthermore, the revenue from oil had been deployed in procuring military equipment, which has influenced the current “Chadian approach to warfare” in the Lake Chad and SahelFootnote 3 regions (Pollichieni Reference Pollichieni2016, 1). More importantly, Chad has assumed a regional power in Africa due to its oil income, armament of weapons, and enormous support base from France. According to Griffin, to sustain the economic benefits from the oil, Chad has to “play a role in providing sanctuary to the terrorist movement in Lake Chad” (Griffin Reference Griffin2015, 5). While oil resources from Doba sustain Chadian economy, President Idriss uses the oil wealth to expand his regional influence and ensure the continuation of his regime in Chad. As Byman (Reference Byman2008, 25) argues, that country can use non-state armed groups to “tie down large numbers of troops and security forces of an adversary and weaken the adversary's control over key parts of its territory”. The increasing interest of Chad in the Lake is a critical matter for stability of the region.

Niger and Chad have been accused of allowing Boko Haram to use their territories for refuge, training, transit, attack planning, and recruitment, because “they are complacent and non-committal to the MNJTF operations” (Ebute Reference Ebute2017). In 2015, the MNJTF Headquarters in Baga town were overtaken and captured by Boko Haram, with only the Nigerian troops on the ground. Niger and Chad had withdrawn their own troops because of security risks shortly before the attack on Baga town (Zamfir Reference Zamfir2015, 2). Boko Haram training cells have been found in the Nigerien towns of Zinder and Diffa (Zenn Reference Zenn2013). Comolli has reported that the Zinder area is a natural conduit for militants moving between Northern Mali and Northern Nigeria. For instance, during the emergency operations in Yobe State in May 2013, 200 trucks carrying alleged Boko Haram militants were seen crossing into Niger ahead of the military arrival (Comolli Reference Comolli2015, 90). The town of Diffa, a close border to Borno State, is described by local officials as Niger's “frontline” in the Boko Haram insurgency. The al-Barnawi faction controls Diffa areas, and the faction “has claimed a string of attacks just across the border over the past 2 years. This predominately occurs in the Diffa department of the Diffa region, although attacks also occur in Maïné-Soroa and N'guigmi departments as well” (Mahmood and Ani Reference Mahmood and Ndubishi2018, 8). Zinder and Diffa towns are oil-producing areas in Niger (predominantly Kanuri indigenes) and they have cultural and historical ties with Kanuri ethnic groups that dominated the Boko Haram leadership. Even though the borderlands between Niger and Nigeria are mostly ungoverned areas, the activities of Boko Haram have not deterred oil exploitation by the government of Niger, due to the alleged tacit non-aggression pact between Nigerian neighbors and Boko Haram. Co-ethnic groups across the border, as many Kanuri ethnic groups are found in Niger, Cameroon, and Chad, have contributed to the recruitment of Boko Haram members and act as safe havens for the militant groups from Nigeria. These are resources required by organized armed groups against state authority.

In Cameroon, Boko Haram members reside in big numbers in the towns of Fotokol, Kousseri, Mora, and the border of Banki-Amchide, where the sects facilitate “trans-border operations” and “regroup after attacks in Nigeria, preparing for the next attacks” (Zenn Reference Zenn2013). The ICG reports that “a senior Nigerian state security official revealed that Mohammed Yusuf stated that his weapons came from Chad, Cameroon, and Niger” (ICG 2016b, 8). Prior to 2015, counterterrorism approaches in Cameroon, similar to Chad and Niger, were merely a ban on wearing the burqa Footnote 4, restrictions on begging, surveillance of religious Quranic schools and mosques, more frequent identity checks, and the use of informants (ICG 2016a, 19). Evidence of Boko Haram terrorists escaping into Cameroon or Niger and Chad for refuge after strikes in Nigeria abounds, during which time, they will recuperate, re-energize, re-arm, and re-surface to attack new targets in Nigeria. Boko Haram is reported to have cells located in Cameroon borderlands of the Gwoza hills from where the militant group launches offensive attacks against the Nigerian government and citizens (Comolli Reference Comolli2015, 89). The Nigerian government had often criticized the Cameroonian government for insufficient military action against the militant group, which explains the possible reason why Boko Haram groups have found Cameroon a convenient place to retreat and regroup.

The lackluster attitude of states that contribute troops to the Multinational Joint Military Task Force (MNJTF), particularly Cameroon, Chad, and Niger, supports the assertion of a tacit, non-aggression pact between Boko Haram and Nigerian neighbors. Comolli (Reference Comolli2015, 87) states that Shekau's operational stance toward the governments of Niger, Chad, and Cameroon is a non-confrontational approach. These countries have reciprocated by being reluctant to launch a major crackdown against Boko Haram for fear of retaliation. The MNJTF mandate is to forge military collaboration to possibly counterattack Boko Haram in the Lake region, but for inexplicable reasons, Chad and Niger pulled out from the MNJTF operations in 2013 and 2014, respectively, resulting in limited “troops to adequately guard the large border region” (Pate Reference Pate2015, 27). Where there is effective military collaboration among nations, the security forces from one country normally pursue insurgent members across each border. This is contrary to MNJTF collaboration. Cameroon was reluctant to grant Nigerian soldiers the “right of hot pursuit” across their common border, so also Niger (ICG 2016b, 27). Over the years, Boko Haram groups have been attacking Nigerian security formations, killing security personnel, or disarming them (ICG 2017; Olojo Reference Olojo2018). Quite recently (July 26, 2017), no fewer than 19 soldiers and 33 civilians were killed by Boko Haram when the security forces were escorting a Nigerian oil exploration team to the Lake Chad region. In 2018 alone, ISWAP successfully launched 18 attacks on military formations, and for the second time, overran and dislodged soldiers at the MNJTF military base in Baga (The Guardian (Nigeria) newspaper, December 1, 2018). Statistics of successful attacks on military formations indicate a dominance of 70%. What this translates into is that out of 20 military bases in northern and central Borno where Nigerian troops were in control, 14 had been overrun or altogether shut down by Boko Haram groups (Salkida Reference Salkida2019). The recent successful attacks are attributed to the Nigerian problem with Chad and the internal security of Chad, which resulted in the Chadian government “pulling away their troops manning their own border around Lake Chad” (Terhemba Reference Terhemba2018). The Boko Haram strategy is to unsettle the military across the Lake Chad region thereby ensuring that no Nigerian security force or scientist would like to visit the area for oil prospecting, thereby denying the Nigerian government the control of their Lake Chad oil territory.

This validates Byman's (Reference Byman2008, 25) assertion that supporting terrorist groups, particularly harboring and using terrorists to attack another country, is to “tie down large numbers of troops and security forces of an adversary and weaken the adversary's control over key parts of its territory”. Further, the precision, frequency, and the extent of damage on Nigerian security personnel have lent credence to Richard Murphy's claim that Boko Haram deployed and used sophisticated weaponry combined with accurate intelligence resulting to a successful and deadly ambush against the oil exploration team. Both considerations suggest State backing for the terrorist groups (Thisday (Nigeria) newspaper, 2017). Overall, it may be argued that energy terrorism is also a criminal activity aimed at causing substantial losses to the national economy. Makarenko (Reference Makarenko2003) identified seven types of attacks on the energy sector, of which three are directly related to the Lake Chad energy security. These are (a) invading or capturing energy facilities and taking captives; (b) direct armed attacks on the workforce of oil equipment or gas processing plants; and (c) kidnapping the employees of energy companies, which happens frequently. Wherever these forms of attacks happen, or are likely to happen, they have a great harmful effect on oil workers and facilities. President Muhammadu Buhari reports that Boko Haram has a “renewed strategy of increasingly mining the general area”, which is facilitated by the group's use of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) for surveillance, thereby succeeding in restricting Nigerian soldiers to sitting ducks in their trenches (Vanguard (Nigeria) newspaper, November 29, 2018). By the use of UAVs, Boko Haram has succeeded in its tactical approach of restricting the patrol of Nigerian troops in the Lake Chad region, which invariably weakens the Nigerian government's effective occupation of its territorial boundaries as well as access to other natural resources.

From a strategic point, France considers Lake Chad and Sahel regions as areas of strategic importance, which serve the economic and political interests of Paris. France's intervention against Boko Haram started when the terrorist group attacked Chad and Cameroon. France quickly noted, officially, that “there is a zone of stability, including Chad, Cameroon, and Niger that must not be destabilized” (Griffin Reference Griffin2015, 4). France quickly deployed “troops to Diffa in Niger to support Nigerien forces, as well as a second detachment to Cameroon”, and “French planes were carrying out reconnaissance missions on the Nigerian border on behalf of Chad, Niger, and Cameroon” (Griffin Reference Griffin2015, 4). France's deployment of war airplanes along the borders of Chad, Cameroon, and Niger is against the background of France's “pursuit of strategic goals” as was the case in the Gulf of Aden in 2008 when France supported the Gulf of Guinea countries in their commitment to securing their maritime area against the al-Shabaab (Ismail and Sköns Reference Ismail and Sköns2014, 45). The impact of France's border surveillance on the Nigerian borders has been minimal, when considered alongside France's Operation Serval and Operation Barkhane forces that restored political order in Mali within a short period. France's role in the counterinsurgency in Nigeria has not been substantial, except the Paris Summit in May 2017, organized to intensify regional security, and the provision of financial support of €25 million in military funding for the fight against Boko Haram and €17 million for humanitarian support to the four Lake Chad countries (Hickie, Abbott and Clarke Reference Hickie, Abbott and Clarke2018, 5). An international civil rights organization, Save Humanity Advocacy Centre (SHAC), has accused France and some business operatives in France of having a substantial interest in supporting and sustaining the Boko Haram terrorist organization. SHAC identifies France's support for the terrorist group to include “airdropping weapons and provisions to Boko Haram terrorists; provision of training as evidenced in the French nationals among captured fighters on several occasions; and provision of military grade intelligence on troops’ movement to the terrorists” (Vanguard (Nigeria) newspaper, August 16, 2017). In 2015, eight French nationals were arrested for fighting on the side of Boko Haram. Mr Lauren Fabuci, French Foreign Minister, requested Cameroonian forces to turn over the suspects to the France government. Since then, there has been no credible information in terms of their trial (Murphy, Thisday (Nigeria) newspaper, August 28, Reference Murphy2017). This technical and financial support from France, according to the SHAC, allegedly facilitated the July 26, 2017 Boko Haram deadly attacks on Nigerian government troops and civilians in search of oil in the Lake Chad area.

What France has not given up is its obsession with the energy in the Sahel and Sahara areas. In 2007, French nuclear power giant, Areva, harnessed around 40% of its uranium supply from Niger, despite losing the monopoly over Niger's uranium (Moncrieff Reference Moncrieff2012, 16). France's oil supply from Cameroon, which precedes the discovery of oil in the Lake Chad, is based on France's economic pacts with Francophone countries. Strategically, oil and uranium continue to be of great importance to France. The reputation of French politics in Africa is rather poor. Tull (Reference Tull2017, 5) notes that France is known in the diplomatic circle as a Western country that pursues her “narrow economic and political interests, or having a penchant for questionable practices (‘mallettes’) and a tendency to prop up dictators” without regard to democratic values, human rights, etc. France's non-committal attitude toward the Boko Haram fight is due to their profound economic interest—oil and uranium from the Lake Chad areas to support its energy needs. More so, France's interest in the Lake Chad region is well known, based on colonial heritage. France continues to exert influence on the political and economic affairs of its former colonies. For instance, a French company carried out the groundwork for the laying of the Chad–Cameroon oil pipeline. Coface, a French company, invested $200 million in the $4.2 billion Chad–Cameroon pipeline project (Gary and Reisch Reference Gary and Reisch2005, 6), while Satom, another French firm, “is heavily involved in the various public works currently underway, which are financed from oil revenues” (ICG, 2009, 13). The confluence of these factors explains the proxy energy security conflict/war at play in the Lake Chad region. It is plausible that an Islamization agenda is not necessarily defining the Boko Haram activities, but rather the natural resources politics in the Lake Chad region. As Hoeffler (Reference Hoeffler2012) argues that some conflicts are defined and pursued by a common interest as well as private benefits as the motivator. Probably, there is also a theory of reducing Nigeria's international power by creating additional “State” of less worth in the Lake Chad area.

Nigeria's explorations of oil from the Lake Chad basin, which extends through Yobe, Borno, and Adamawa States, have been disrupted by Boko Haram insurgency. The Nigerian government had over time engaged the services of foreign technical personnel as well as geologists in the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation (NNPC) for commercial oil exploration, but the experts have repeatedly abandoned the areas for fear of being killed or kidnapped by terrorist groups. While on the contrary, oil drilling continues unabated in Doba in Chad, production is going on in the Zinder and Diffa oilfields of the Republic of Niger, and the Chad–Cameroon pipeline flows from the Doba basin field is uninterrupted despite the activities of Boko Haram groups. This may have provided Chad, Niger, and Cameroon unfettered access to oil under Nigeria's soils through 3D oil drilling from within its territorial borders. This is, however, legally permitted under the “Rule of Capture”, in as much as the drilling is done within the individual's territory and does not extend into the neighbor's land. Extractive sites are magnets for militias, whether moved by grievances or mere greed, and oil exploitations can go on during fighting. Wenar (Reference Wenar2016, 50) states that while the second Iraq war was going on, “armed groups were making at least $200 million a year through oil-related extortion”. Records have it that while the insurgency is ravaging the Nigerian economy, Chad became Africa's 10th largest oil producer in 2010 and the country's national budget moved from a modest $670 million to more than $2.8 billion in 2014. Cameroon, also, earns about $20.40 million from the pipeline royalties, and the oil revenues from Zender and Agadem turned to be the mainstay of the Nigerien economy.

Boko Haram groups have cashed in on the narrow and divergent interests of Nigeria and its riparian neighbors in three ways. First, between 2014 to date, the two factions of Boko Haram have strong control of Sambisa forest and Lake Chad areas. The al-Barwani faction entrenched its presence in the northern Borno areas, and central areas of Borno and neighboring Yobe state in Nigeria; in Cameroon, the faction is active in the Logone-et-Chari department; in Niger it controls the Diffa department; while in Chad it is found in the Lac region. Also, Shekau's faction maintains its stronghold in Sambisa, south-central Borno and Cameroon near the Mayo-Sava and Mayo-Tsanaga departments (Mahmood and Ani Reference Mahmood and Ndubishi2018, 22–23). Second, the control of these areas, particularly the Lake Chad region, controlled by the al-Barwani faction, helps the faction to move closer to the realization of the objective of the ISWAP in an attempt to rekindle the ideological preaching of his late father (Muhammad Yusuf). Third, these dynamics have increased the successful, and most often, large-scale attacks on Nigeria's military formations and the looting of weapons and materials, and sometimes cattle rustling, control of fish businesses, and taxing of grain sellers. These have increased Boko Haram's strength and resilience.

There is sufficient evidence that the trio of Francophone Nigeria neighbors have not done enough to combat Boko Haram (Zenn Reference Zenn2013; Comolli Reference Comolli2015; Griffin Reference Griffin2015; ICG, 2016b), and it is a possibility that they intend to capture the rich oil deposit in the region and turn over the real estate to their colonial master for the full exploration of crude oil, gas, and uranium. François Hollande, former President of France, admitted after the Nigeria–Paris security summit in 2014, that Nigeria is not linked to France historically, but “very serious terrorist acts have been taking place for months in Nigeria and Cameroon, and they risk spreading across the region” (Hollande Reference Hollande2014, interview), and that France therefore needed to stem the tide of insurgency from sauntering into the zone that should not be destabilized. France does not appear to lose much economically or politically if Nigeria is destabilized. In fact, France stands to gain, by leveraging on a colonial economic pact with Francophone countries for greater access to the Lake resources. Why they are not paying much attention to fighting Boko Haram could be because of a tacit or secret agreement not to disrupt their economic operations, including oil exploitation in the area.

CONCLUSION

The large oil reserve in the Lake Chad makes the region a top national security priority. Chad's regional power is influenced by its current oil resources, Niger's Agadem oilfield has increased its national income, and Cameroon benefits enormously from the Chadian oil pipeline, while Nigeria projects $20 billion yearly income from the Lake Chad oil extraction. France's emphasis on the stability of Chad, Cameroon, and Niger is, also, rooted in the pursuit of alternative energy security supply from the Lake Chad basin. The high probability of large-scale conflict in the Middle East and the Syrian war makes energy security of European and American countries increasingly threatened, thereby resulting in a shift to many prospecting sites in Africa, particularly the Lake Chad basin.

The control of the Lake Chad basin is strategic, both for the riparian countries and France's future and present energy security. Securing Lake Chad's natural resources, most importantly oil and natural gas, remains a top national security priority among states in the Lake region. Most nations, according to Klare (Reference Klare2001), will not “surrender vital national interests” because natural resources are synonymous with national security. Oil as an important natural resource will continue to shape international conflict, and since the beginning of oil exploration in the Lake Chad basin, oil products have been a key element of the riparian states' national interest and contestation. The “greed-and-grievance” theory explains this configuration of forces behind the insurgency in the Lake Chad region.

Energy dimensions of the Boko Haram activities need to be given careful attention, not only because of the current shift in the national interest, but because some states are leveraging on the energy extraction from the Lake Chad region at the expense of others. The shift in the character of Boko Haram activities from internal conflicts of political opportunists as well as radical Islamist ideology to more regionalized interventions is possibly motivated by interstate competition for resources. Boko Haram and its splinter group (ISWAP) know that a strategic control of the economic mainstay of the Chad Basin cross-cutting fishing, all-season farming, water, and control of cross-border trade routes will be good bargaining instruments. To view Boko Haram from the perspective of Islamic extremism alone may be misleading, because evidence of some non-state arms used as a tool of statecraft is a way to extend their strategic interest. Recently, President Donald Trump included Chad in the list of the United States' travel ban, because Chad “does not adequately share public safety and terrorism-related information and fails to satisfy at least one key risk criterion” (Allison Reference Allison2017; The Guardian (US) news, September 25, 2017). This agrees with allegations against the Chadian government of harboring the factional Boko Haram leader, and the government doing very little to discourage recruitment of Chadian nationals into Boko Haram.

Some areas of Cameroon (such as Fotokol, Kousseri, Mora, and the border of Banki-Amchide) are havens for terrorist groups due to government indifference, while in Niger, the terrorist group recruits Nigerien citizens and operates cells with less government reactions. The Nigerian government had often criticized Cameroon for not doing enough to contain the expansion of violent extremism in its territory, which is possibly one of the reasons Boko Haram had found in Cameroon a convenient area to retreat and regroup (Comolli Reference Comolli2015, 89). The law of neutrality demands that a non-aligned state should not permit terrorist group(s) to use its territory for recruiting combatants or forming units to assist them. If the neutral state fails to respect that obligation, it loses its neutrality. In Nigeria, two former Senate Presidents have claimed that the terrorist attacks in Nigerian territory are conceivable because of the collaboration of Nigerian neighbors.

Machiavelli (Reference Machiavelli2003, 158) asserts that “to know in war how to recognize an opportunity and seize it is better than anything else”. The Machiavellian principle or dictum seems to govern the behavior of Chadian, Cameroonian, and Nigerien governments against Boko Haram activities. These countries prefer a narrow concept of defense policy (tacit non-aggression pact with the insurgent groups) to secure their countries from direct attacks by the insurgent groups instead of embracing multilateral cooperation that addresses cross-border vulnerabilities. More importantly, political leaders of Cameroon, Chad, and Niger consider Nigeria as probably having a negative political influence on their citizens due to Nigeria's democratic credentials, which do not encourage a sit-tight leadership through abrogation of a constitutional limit of power, as witnessed in Cameroon, Chad, and Niger.

This raises another important question about “a secure immediate neighborhood” through the MNJTF. Although Nigeria is a major financer of MNJTF, and contributes the largest number of troops, the effectiveness of the regional force has been significantly weakened by the narrow state interest against the regional order. While it is credible for Chad and Niger in alliance with France to contemplate the use of armed forces to support internal stability in countries such as Mali and Côte d'Ivoire, it is not credible to adopt the same momentum of force against Boko Haram. The G-5 Sahel Joint Force, of which Chad and Niger are members, agreed to pursue terrorist elements into the territory of a neighboring country to the extent of 50 km into each country on both sides of the border, but Chad and Niger agreed to increase this to 100 km on both sides of their joint border in the Eastern Sector (UNSC 2017, 5). On the contrary, Niger had refused Nigerian troops' right of hot pursuit in spite of the same agreement existing in MNJTF operations.

The longer the Boko Haram terrorist groups are allowed to fester, the more likely regional stability could be potentially at risk. The insurgent groups have taken control of most of the islands of Lake Chad and Sambisa forest, and openly associated themselves with al-Qaeda international groups through the Maghreb region. A conglomeration of terrorist groups is gradually building up in the Lake Chad basin. Smail Chergui, the AU's Commissioner for Peace and Security, warned that African nations would need to work closely with one another and share intelligence to counter about 6,000 ISIS fighters dislodged in Syria and Iraq relocating to the Sahel region in Africa (Inwalomhe Reference Inwalomhe2019). The tacit supports Boko Haram and ISWAP enjoy from the Nigerian neighbors will likely create a unique problem of terrorist regimes in the Lake Chad basin, thereby enthroning the culture of terrorism as an instrument of regime change in sub-Saharan Africa. States should not knowingly permit any group to convert and use their terrain in a way that jeopardizes other states, including the use of its territory as a base for terrorist attacks. This is a basic principle in international relations, and, as long as some states maintain a friendly disposition toward terrorist interests or use the group in a proxy war, the possibility of the groups transforming from their initial aim(s) to a more rewarding objective(s) is potent. Rebellion is an investment either defined in the loot of commodities or where the payoff is to attain some political gains in the future. Boko Haram and its splinter group, no doubt, is partly motivated by economic gains, whether defined by oil and gas resources or the control of informal trade routes of Lake Chad region and Sahel areas.

Appendix A

Figure A1. Cartography of the different states of Lake Chad between 1973 and 2011. Source: LCBC, 2016, 30.