INTRODUCTION

Asian Americans are an increasing proportion of the U.S. electorate. A 2017 Pew Research Center Report notes that Asians have outnumbered Latina/os in the percentage of new immigrant arrivals since 2010. This racial/ethnic group has reached an all-time high of 38% of all immigrants arriving in the United States (Lopez, Ruiz, and Patten Reference Lopez, Ruiz and Patten2017). Given this growth, it is continually vital to consider how Asian Americans integrate into their host political system.

As summarized by Wong et al. (Reference Wong, Karthick Ramakrishnan, Lee and Junn2011), research on Asian American political engagement often goes beyond socioeconomic models of behavior. This work often emphasizes the critical roles played by factors such as residential contexts, political orientations, recruitment, racial identity, and immigrant socialization. They also identify membership and involvement in civic associations as a key factor for Asian American participation. Relatedly, scholarship has theorized that religious institutions are particularly powerful motivators of participation among racial/ethnic minorities such as Asian Americans. Civic voluntarism and resource models of political behavior conceptualize churches as sites for the development of civic skills and politically salient group ties, which in turn foster greater participation among congregants (Wald, Owen, and Hill Reference Wald, Owen and Hill1990; Peterson Reference Peterson1992; Verba, Schlozman, and Brady Reference Verba, Lehman Schlozman and Brady1995; Greenberg Reference Greenberg2000; Djupe and Grant Reference Djupe and Tobin Grant2001; Schwadel Reference Schwadel2002; Wong, Lien, and Conway Reference Wong, Lien and Margaret Conway2005). Examinations of the role of the church in mobilizing political action among African Americans emphasize three components. One, development of politicized racial consciousness within congregants; two, the steering of congregants toward political action through social pressure; and three, the provision of resources and services that lower the costs of participation (Tate Reference Tate1991; Calhoun-Brown Reference Calhoun-Brown1996; McClerking and McDaniel Reference McClerking and McDaniel2005).

This study imagines Christian churches as sites of a different type of identity formation and development for Asian American congregants. We highlight a component other than the acquisition of civic skills, the cultivation of racial identity, or the lowering of costs for participation. Churches cultivate a unique bonding social capital derived from Asian American congregants' perceptions that they hold similar political views with other church members. We demonstrate this particular type of bonding capital both strengthens intragroup ties and animates greater political participation among Asian Americans, across a wide domain of actions. Further, we show that this perceived political homogeneity within the church plays a greater role in fostering Asian American identity and political behavior than racial homogeneity within the church. We thus expand upon extant literature, which has identified racial homogeneity as important for Asian American political activity. By uncovering the unique influence of Asian American churchgoers' perceptions of political homogeneity on their political behavior, we add new insight into the role churches have in providing meaningful political socialization and integration to a group steadily increasing in number and influence within the American polity.

Informed by Han's (Reference Han2016) social theory of civic voluntarism, we offer an account of how particular religious institutions motivate Asian Americans. We argue they do so by cultivating a politically salient and socially relevant identity on the basis of shared ideological views. We distinguish the effects of this shared ideology within the pews from that of shared race. The development of bonding social capital among politically like-minded congregants produces distinct effects on Asian Americans' sense of interconnectedness to the racial group. This interconnectedness increases their motivation to act to advance the group's political interests.

We analyze the 2016 Collaborative Multi-Racial Post-Election Survey (CMPS) to examine the relationships between varying types of homogeneity, Asian Americans' senses of racial linked fate, and their participation in a variety of political actions. Our analyses reveal that Asian American churchgoers' intragroup racial ties and the likelihood of participating in multiple forms of action are significantly increased by political—but not racial—homogeneity within the pews. We posit the relationships found between political homogeneity, identity, and participation among Asian Americans reveal a distinct pathway through which churches incorporate group members. We discuss the implications of this novel relationship for our understanding of the role churches have in shaping Asian Americans' navigation of politics.

ASIAN AMERICAN CHURCHES AS SITES OF IDENTITY, SOCIAL CAPITAL, AND POLITICAL ACTION

The general departure of Asian Americans from the conventions of recruitment and socioeconomic models of participation contributes in no small part to the critical role played by churches in stimulating the group's political behavior. Despite Asian Americans on average having higher levels of education and household income, these factors do not serve as strong indicators of participation for this group (Nakanishi Reference Nakanishi1991; Cho Reference Cho1999; Junn Reference Junn1999; Lien Reference Lien2010; Wong et al. Reference Wong, Karthick Ramakrishnan, Lee and Junn2011). Wong et al. (Reference Wong, Karthick Ramakrishnan, Lee and Junn2011) find little association between socioeconomic status and being registered to vote or having voted in elections. Despite the recruitment of the group into politics having a positive effect on the likelihood and frequency of political participation, both the Democratic or Republican Parties have been found to rarely mobilize Asian Americans (Wong Reference Wong2008; Kim Reference Kim2007). Ramírez, Solano, and Wilcox-Archuleta (Reference Ramírez, Solano and Wilcox-Archuleta2018) find that while Asian Americans may be contacted to participate by other minorities, they are neglected by White recruiters. As an alternative to formal institutions of recruitment, community-based organizations may be more effective at recruiting Asian Americans into politics (García-Castañon et al. Reference García-Castañon, Huckle, Walker and Chong2019).

Churches are a type of institution that fosters political activity among Asian American congregants. The aforementioned development of civic skills that are translatable to political life, such as public speaking, reading, or writing skills, is one such reason for churches' mobilizing effect (Cherry Reference Cherry2009). Additionally, churches expose members to political information and spur greater political interest and sophistication. This results in increased levels of political activity among congregants (Wald, Owen, and Hill Reference Wald, Owen and Hill1990; Harris Reference Harris1994; Jones-Correa and Leal Reference Jones-Correa and Leal2001).

Beyond developing political skills and interests, churches have been shown to foster stronger senses of group consciousness among members; this is especially true for racial and religious minority groups. As previously alluded to, African American churches have long been heralded as sites for promoting strong intragroup ties and senses of politicized racial identity among members (Harris Reference Harris1994; Dawson Reference Dawson2003). This consciousness engenders greater participation among African Americans, even in the face of resource barriers to action (Miller et al. Reference Miller, Gurin, Gurin and Malanchuk1981; Chong and Rogers Reference Chong and Rogers2005). Similarly, examinations of Muslim Americans demonstrate that active participation in mosques fosters feelings of group consciousness. This in turn elicits greater political activity from the group (Jamal Reference Jamal2005; Ocampo, Dana, and Barreto Reference Ocampo, Dana and Barreto2018).

Finally, churches can stimulate participation by cultivating social capital among members. Defined as the “features of social life—networks, norms, and trust that enable participants to act together more effectively to pursue shared objectives” (Putnam Reference Putnam2000), these strong social connections encourage and incentivize individuals to take civic and political action. Social capital has been especially instrumental in stimulating political activity among racial minorities (Sundeen, Raskoff, and Garcia Reference Sundeen, Raskoff and Cristina Garcia2007; Liu Reference Liu2011). Scholars draw a distinction between two different types of social capital. Bridging social capital is developed among people creating ties within heterogeneous groups. Bonding social capital is engendered within homogeneous groups. Bridging capital has been touted as more effective at increasing democratic norms and fostering political participation than bonding capital (Gutmann Reference Gutmann1998; Schlesinger Reference Schlesinger1998).

A contrasting image of bonding social capital, however, emerges from work focusing specifically on racial/ethnic minority groups. For instance, while Uslaner and Conley (Reference Uslaner and Conley2003) argue that members of homogeneous organizations may actually be less involved in civic participation, Liu (Reference Liu2011) finds that Asian Americans and African Americans who attend churches comprised of a majority of racial in-group members are more likely to vote. He argues the bonding social capital resulting from the racial homogeneity within these churches provides congregants with stronger attachments to their church. Those who feel more invested in their church are more likely to participate in politics, as they have more organizational skills and capacity to do so. This work emphasizes the importance of racial homogeneity in facilitating ties that increase political action. Yet, there is ample reason to question whether racial homogeneity is the most effective vehicle through which social capital cultivated in churches influences Asian Americans.

There are potential constraints on the development of a politicized pan-ethnic racial consciousness among Asian Americans. These include the large proportion of group members who are born outside of the United States and higher general levels of Asian American integration within racially heterogeneous residential and social spaces (Junn and Masuoka Reference Junn and Masuoka2008). While significant numbers of Asian Americans express a sense of linked fate with other Asian Americans, they often do so at lower rates than Latina/o and African Americans. Further, this expression varies across national origin (Lien, Conway, and Wong 2003; Masuoka Reference Masuoka2006; Sanchez and Masuoka Reference Sanchez and Masuoka2010). Finally, the effect of Asian Americans' intraracial group ties and group consciousness on their political behavior is less consistent relative to African Americans (Leighley and Vedlitz Reference Leighley and Vedlitz1999; Wong, Lien, and Conway Reference Wong, Lien and Margaret Conway2005; McClain et al. Reference McClain, Johnson Carew, Walton and Watts2009).

The salience of pan-ethnic racial identity and its translation to political behavior is less pronounced for Asian Americans relative to other minority groups such as African Americans. Accordingly, we posit that a key to political participation among this group is a bonding capital emergent from other perceived commonalities. Adapting Han's (Reference Han2016) relational organizational model, we examine Asian American participation as an expression of a particular social identity fostered within the church—one rooted in ideology. Asian American churchgoers can develop mutually responsive relationships based upon shared political views. These relationships in turn propel churchgoers to be politically active, as a demonstration of their relational value to the ideologically homogeneous networks they have established (Baumeister and Leary Reference Baumeister and Leary1995; Leary Reference Leary1996; Leary Reference Leary, Fiske, Gilbert and Lindzey2010). By uncovering a positive relationship between perceptions of shared political views within the church and greater political participation among Asian Americans, we identify a novel pathway through which bonding social capital within a civic institution can spur greater political engagement among this group.

STRUCTURAL, RELATIONAL, AND COGNITIVE SOCIAL CAPITAL IN POLITICALLY SIMILAR CHURCHES

Following Han's (Reference Han2016) view of civic institutions as schools of democracy, we contend that Asian Americans can achieve two ends within churches. One, they can learn about their own political orientations. Two, they can forge politically consequential relationships with others carrying similar orientations. In this section, we address how churches supply Asian Americans with the components of social capital identified by Nahapiet and Ghosal (Reference Nahapiet and Ghoshal1998)—structural, cognitive, and relational—as they effectively incorporate the group within the fabric of political life.

Churches first provide structural social capital by simply offering a physical space that facilitates social exchanges that might not otherwise occur. Relative to non-Western religious affiliations, Christian churches are uniquely impactful in this domain. They offer frequently occurring religious services, allowing for more chances for regularized contact among members (Emerson and Smith Reference Emerson and Smith2000; Jeung Reference Jeung2005; Wong et al. Reference Wong, Karthick Ramakrishnan, Lee and Junn2011).

This regularized contact allows for the development of awareness (cognition) about “shared representations, interpretations, and systems of meaning” (Klandermans and van Stekelenberg Reference Klandermans, van Stekelenburg, Huddy, Sears and Levy2013). As Asian American congregants become cognizant that their own political views align with those of fellow parishioners, they subsequently develop a shared identity based on this commonality. This identity can in turn engender greater political engagement. Once an awareness or “consciousness” of similarity is realized, shared values can mobilize individuals to take political action (Gurin, Miller, and Gurin Reference Gurin, Miller and Gurin1980). These researchers note that members of a salient group sharing a set of similar political beliefs are more likely to take up political action.

It should be stressed here that we do not posit that an identity forged within the church on the basis of shared political beliefs utilizes the same mechanism to promote political participation as an identity forged on shared race and the subsequent development of racial group consciousness. A key element of racial group consciousness is grievance with the group's perceived subjugated sociopolitical status. Consequently, group consciousness propels action by inciting an individual's sense of responsibility to act to advance the collective standing of the group (Miller et al. Reference Miller, Gurin, Gurin and Malanchuk1981; McClain et al. Reference McClain, Johnson Carew, Walton and Watts2009). Neither of these factors must be present in order for an identity based upon shared political views to animate action among Asian Americans. The simple act of engendering a sense within individual churchgoers that fellow parishioners are on the same political “team” as them can incentivize political action. This is due to increasing their sense of belonging within the political realm and their emotional investment in politics. For instance, Groenendyk and Banks (Reference Groenendyk and Banks2014) find strong partisans are more likely to be politically active than those who weakly identify with a party. This is because the sense of close affiliation with this team facilitates perceptions of agency and a mutual obligation to advance the party's aims.

Accordingly, increased political involvement on the basis of shared political views within the church need not require the rise of salient threat to that identity. Such threat is a central component of the pathway from racial group consciousness to action. On the contrary, participation on the basis of shared ideology within the church can serve as an expressive outlet of the relational ties that Asian American churchgoers have forged with fellow parishioners (Rogers, Gerber, and Fox Reference Rogers, Gerber, Fox and Shafir2012; Han Reference Han2016). Given the variations in Asian Americans' possession of pan-ethnic racial identity, as well as the generally lower levels of racial consciousness exhibited by this group relative to other minorities, the potential of political homogeneity within the church is uniquely potent for this group. Further, it should be more impactful than the potential influence of racial homogeneity.

Lastly, Grannovetter (Reference Granovetter1973) notes the means through which the relational component of social capital can increase participation. Both recurring interaction and shared underlying values between those interacting facilitate the development of strong relationships. This highlights the potential value of bonding capital—especially for a group containing members who may still be socializing into American politics. Through offering Asian American members recurring interactions with politically like-minded people, churches are uniquely positioned to serve as sites for the building of mutually trusting and respectful relationships. This leads to greater participation in cooperative activity (Lind and Tyler Reference Lind and Tyler1998; Simon and Sturmer Reference Simon and Sturmer2003). Chen (Reference Chen2002) demonstrates the particular value of relationship ties forged in churches between Asian Americans. Thus, the social ties being developed within these spaces can have outsized impacts on how members of the group subsequently decide to navigate the political environment. We offer here an account of how churches can foster Asian American political participation through cultivating a bonding social capital on the basis of homogeneous political views held by parishioners. Political homophily in the church space serves as a critical site for bonding social capital to occur. When the church is used as a structure for members to gather, a cognitive awareness and development of strong social relationships are fostered. This allows for a greater likelihood of political participation, as the decision to take political action shifts from an individual to a group-based calculation.

Previous studies that have examined the role of religion for Asian Americans indicate that churches increase participation only for a limited set of political actions. Wong et al. (Reference Wong, Karthick Ramakrishnan, Lee and Junn2011) and Cherry (Reference Cherry2009) find that Christian religious affiliation and church attendance are positively associated with an electoral activity such as registering and voting, yet not system-challenging actions such as protesting and signing petitions. Liu (Reference Liu2011) explores the relationship between racial homogeneity in the church and voter turnout solely. Yonemoto (Reference Yonemoto2009) argues that Asian American churches encourage a kind of political involvement that affirms rather than disrupts the political system. Informed by this past research, we explore potential variations in the effects of church political homogeneity on three types of activities: voting, conventional activities such as donating to or volunteering for political campaigns, and unconventional actions such as protesting.

HYPOTHESES

Since we have argued that the bonding capital derived from political homogeneity can be a more effective facilitator of Asian American participation than the capital formed from racial homogeneity, we test the respective influence of both of these factors on Asian American participation. We also compare the effects of political and racial homogeneity within churches on Asian Americans' racial group ties. We test the following competing hypotheses.

Consistent with our claims, we expect to find a strong positive association between Asian Americans' perceptions that members of their church share their political views and their likelihood of voting (H1) and participating in non-voting electoral activities such as donating and canvassing (H2). As with other aforementioned work, we hypothesize that there should be a weaker positive association between Asian Americans' perceptions that members of their church share their political views and their likelihood of participating in contentious political activities, such as protesting and boycotting (H3).

We test an alternate set of hypotheses to compare the effects of racial homogeneity within churches. We hypothesize that relative to church political homogeneity, racial homogeneity within Asian Americans' churches will have a weaker positive association with voting (H4) and non-voting electoral activities (H5). Finally, we test our claim that the bonding capital derived from political homogeneity can be more meaningful than racial homogeneity for the cultivation of a politically salient identity among Asian American churchgoers. We hypothesize that Asian Americans' perceptions that members of their church share their political views will have a stronger effect on their sense of racial group linked fate than the effect of racial homogeneity within the church (H6).

DATA AND METHODOLOGY

We analyze the 2016 Wave of the Collaborative Multi-Racial Post-Election Survey (CMPS). The CMPS is a web-administered study that attained large samples of multiple racial/ethnic minority groups by employing a stratified listed and density quota-sampling approach (Barreto et al. Reference Barreto, Frasure-Yokley, Vargas and Wong2017). Additionally, the survey was offered in multiple languages—including Chinese (simplified/traditional), Korean, and Vietnamese. Of the total 10,145 respondents, 3,006 identify as Asian American or Pacific Islander (AAPI). The demographic characteristics of the AAPI sample are consistent with those of the 2016 National Asian American Survey and the 2012 PEW Asian American Survey (Barreto et al. Reference Barreto, Frasure-Yokley, Vargas and Wong2018).

About 45% of the AAPI sample reports being born outside the United States. The four largest national origin groups comprising the sample are Chinese (32%), Indian (16%), Filipina/o (14%), and Japanese (12%). The CMPS has been used in recent studies of minority political engagement, including examinations of the political behavior of Asian Americans and explorations of how religious denominations affect political preferences across race (Phoenix and Arora Reference Phoenix and Arora2018; Wong Reference Wong2018). In addition to its large AAPI sample, the CMPS is an ideal data set to use because of its wide range of questions about religious affiliation and practices, racial identity, and political participation. To the best of our knowledge, the 2016 CMPS is the only data set that measures perceptions of political homogeneity in the church among such minority groups.

Dependent Variables

We operationalize political participation with three separate measures: voting, non-voting electoral (conventional) participation, and non-electoral (unconventional) participation. The voting variable is a self-reported measure for whether or not an individual voted in the 2016 election. The use of self-reported turnout data follows “a long tradition of political science research,” (Ocampo, Dana, and Barreto Reference Ocampo, Dana and Barreto2018). The non-voting conventional participation variable is an additive index of political activities that includes working on a campaign, donating to political organizations, wearing political advertisements, contacting an elected official, cooperating with others to solve a community problem, and attending political meetings. This variable is coded from zero to six, with one point for each participated in the activity. Non-electoral (unconventional) actions include an aggregate measure of boycotting products for political reasons, protesting or rallying, and signing a petition; this variable is coded from zero to three. In order to test our last hypothesis, we use a standard measure of linked fate that combines two questions: “Do you think what happens generally to Asian American people in this country will have something to do with what happens in your life? Yes or No; Will it affect you: A lot, Some, or Not Very Much?”

Independent Variables

In order to measure church political homogeneity, which we conceptualize as individuals' perceptions that their political views align with those of others in their church, we utilize the survey question asking Asian Americans: “How similar would you say your political views are with most people in your church? Not similar at all, Not very similar, Somewhat similar, and Very similar.” To test our competing hypotheses regarding the influence of church racial homogeneity on identity and participation, we use the following measure where Asian American respondents are asked to “Please indicate the approximate racial/ethnic composition of your place of religious worship or gathering.” Respondents indicated the percentage of Whites, African Americans, Latina/os, Asians, or “Other” in their church.

Control Variables

We build multivariate models that control for key socio-demographic variables. These include an individual's age, gender, education, income level, party identification, ideology, and whether or not they were born in the United States. We also include indicators of psychological engagement such as political interest, political efficacy, and strength of partisan identity. Recruitment into politics is also included via a measure of whether respondents had been mobilized by a political party.

Our theory focuses on the specific role of Christian churches for Asian Americans. Previous scholarship also uncovers denominational differences between Protestants and Catholics. Protestants have been shown to be more likely to participate in politics (Verba, Schlozman, and Brady Reference Verba, Lehman Schlozman and Brady1995; Jones-Correa and Leal Reference Jones-Correa and Leal2001). Thus, in our models, we account for the specific religious affiliation adhered to. We also include a measure of frequency of church attendance. Lastly, to determine how organizational membership aside from religious institutions influence political participation, we include a variable measuring the extent to which individuals are affiliated with and active in other civic organizations.

Methods of Analysis

We first test the relationships between church ideological similarity and voting, conventional, and unconventional participation. Due to the nature of the response outcomes for voter turnout, we run logistic regressions. Along with the logistic regressions, we compute predicted probabilities examining the difference in participation likelihoods among individuals expressing the highest and lowest degrees of political similarity with other members of their church. For the remaining dependent variables, we run negative binomial regressions.Footnote 1

We then test our competing hypotheses by examining the relationship between racial homogeneity in a church and the likelihood to participate at the ballot box. Liu (Reference Liu2011) relied on an alternative measure of this variable. Citing a 2004 Gallup Poll Survey (Winseman Reference Winseman2004) that finds that most Americans who attend church go to one that is racially similar, he uses this information as justification for using the frequency of church attendance as a proxy for racial homogeneity. Using a more direct operationalization of this independent variable, we run models predicting political participation as a function of this precise measure of racial homogeneity. To test our final hypothesis, we run OLS regression models testing the respective relationship of political and racial homogeneity to Asian American Christians' reported linked fate.

RESULTS

Religion among the Asian American community is complex, containing diverse patterns of religious orientations, as noted in Table 1. Our sample from the CMPS 2016 for the most part matches results from the Pew Research Center's 2012 Asian American Survey on religious behavior. A plurality of all Asian Americans identifies as either Catholic or Protestant Christian (~40%). A total of 34% of Asian Americans in this sample have no religious affiliation or are Atheist/Agnostic. Around 20% affiliate with traditionally Eastern religions (Buddhism and Hinduism). While this paper focuses on the political behavior of Asian American Christians, future studies may want to contend with the political participation of Asian American Buddhists and Hindus, given they also make up a sizeable proportion of religious adherents. About 65% of Asian Americans attend a church primarily with others of their race/ethnicity.Footnote 2 Asian Americans are about 50% likely to attend a church in which their political views are similar to other members.Footnote 3

Table 1. Religious orientations among Asian Americans

Note: Data from the Collaborative Multi-Racial Post-Election Survey in 2016. Figures are in percentage terms and may not add up to 100% due to rounding. For Asian Americans (all), n = 3,006; for Asian American (citizens), n = 2,366.

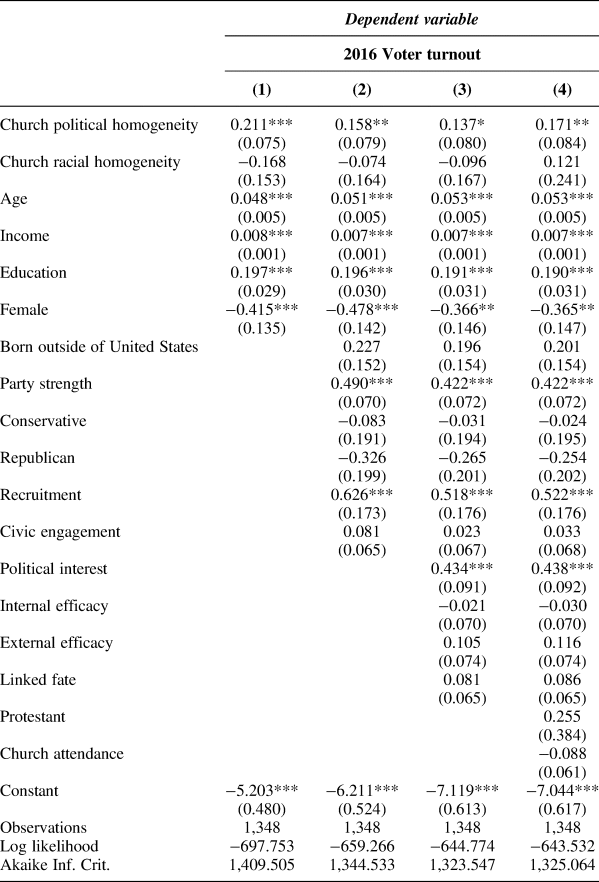

The results reported in Table 2 present various model specifications estimating the relationship between church political homogeneity and voter turnout. Across all models, political homogeneity exerts a strong and positive influence on the likelihood to vote. Further, comparisons of the first two rows of Table 2 reveal that the effect of church political homogeneity exceeds that of church racial homogeneity. Across each model specification, the racial homogeneity variable fails to achieve standard levels of statistical significance. Further, the estimated magnitude of the variable's coefficient is negative in three of the four models. These results provide strong evidence in support of hypothesis 1, while failing to support hypothesis 4. We find a positive association for political homogeneity and a less certain, sometimes negative relationship for racial homogeneity. Figure 1 computes the predicted probability of turning out to vote across varying levels of political homogeneity in one's church, moving from the lowest to highest degrees of ideological similarity. Asian American citizens who attend politically aligned churches are about 11 percentage points more likely than those in politically misaligned churches to vote in national elections. This substantial increase in turnout likelihood underscores the impact that Asian Americans' perceptions of ideological similarity in their churches can have on their participation at the ballot box.

Figure 1. Predicted probability of Asian American voter turnout by the degree of church's political similarity

Table 2. Political homogeneity and voter turnout among Asian Americans

Note: Logistic regression coefficients. Standard errors are reported in parentheses. *p < 0.1, **p < 0.5, ***p < 0.01.

Comparing the magnitude effect size of church political homogeneity with other factors known to influence voting reveals the particularly substantial influence of this dimension of bonding capital on Asian American turnout. Figure 2 displays the estimated changes in turnout as respondents move from their minimum to maximum levels of the independent variable, while control variables are held at their means. According to Figure 2, the effects of civic organizational engagement, linked fate, and other indicators of religious orientation are weaker than that of our main independent variable of interest here, church political homogeneity. The predicted probabilities indicate that a racially homogeneous church advantages Asian American Christians by only 2 percentage points. Asian Americans who perceive their fate is linked with other members of the racial group are about 5.4 percentage points more likely to vote. Being a Protestant increases the likelihood to vote by about 4.6 percentage points. The previously reported effect of 11 percentage points for church political homogeneity stands out amongst these other factors in our model. That the influence of church political homogeneity on turnout is more than double these other factors indicates this type of bonding social capital is a particularly strong predictor of turnout among Asian Americans.

Figure 2. Change in the predicted probability of voting in 2016 among Asian Americans

To further examine the relationship between church racial homogeneity and voting, we re-run the models from Table 2, this time excluding the church political homogeneity variable. Regression results are presented in Table 3. Even so, racial homogeneity within Asian Americans' churches has no statistically discernible effect on turnout (p = 0.51 in full regression model in the fourth column of Table 3). We expected to find a positive association between racial homogeneity and turnout, albeit one weaker than the association between church political homogeneity and turnout (H4). Yet contrary to our expectations and findings from prior studies, we find no such positive association. We find no evidence that attending churches with high concentrations of other Asian Americans facilitates voting.

Table 3. Racial homogeneity and voter turnout among Asian Americans

Note: Logistic regression coefficients. Standard errors are reported in parentheses. *p < 0.1, **p < 0.5, ***p < 0.01.

Previous studies of bonding social capital have generally focused on its relationship to voting. We broaden the scope to analyze its effect on various conventional and unconventional forms of political participation. Tables 4 and 5 report negative binomial regression coefficients and standard errors from models predicting the effect of church political homogeneity on the indices of conventional and unconventional participation, respectively.

Table 4. Church political homogeneity and conventional participation among Asian Americans

Note: Negative binomial regression coefficients. Standard errors are reported in parentheses. *p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

Table 5. Church political homogeneity and unconventional participation among Asian Americans

Note: Negative binomial regression coefficients. Standard errors are reported in parentheses. *p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

Across different specifications of the negative binomial models in Table 4, church political homogeneity remains a statistically significant predictor for conventional modes of political participation. As shown in Model 1 in the leftmost column in Table 4, which controls for sociodemographic variables, for every unit increase in the degree of political homophily, the rate of conventional political participation increases by a multiplicative factor of 1.27. That is, Asian Americans who attend politically homogeneous churches elevate their predicted number of conventional political activities by 27.5 (100 × [e0.243−1] = 27.5)%. The fourth column of Table 4, which controls for the full slate of sociodemographic, psychological engagement, recruitment, civic involvement, linked fate, and other religious-oriented variables, indicates that as the degree of one's church political homogeneity increases by one unit, the rate of conventional political participation increases by a multiplicative factor of 1.08, or an increase in the predicted number of conventional activities by about 8 (100 × [e0.076−1] = 7.8)%. This positive relationship between political homogeneity and non-voting forms of electoral participation supports hypothesis 2.

Comparisons of the first two rows of Table 4 indicate once again that the bonding capital from ideological similarity within the church is a more consistent predictor of electoral Asian American participation than racial homogeneity, supporting hypothesis 5. Across all four model specifications, the coefficient effect for church racial homogeneity is negative and does not reach standard significance in three of four models. Whereas we expected a weakly positive relationship between racial homogeneity and participation (H5), we find this factor to be associated with less activity. As Asian Americans attend churches with congregations comprised of increasingly larger proportions of their racial in-group, they may be less likely to participate in electoral action.

The negative binomial regression results in Table 5 indicate church political homogeneity exerts a much less robust effect on Asian Americans in the domain of contentious forms of political action. This set of findings largely support our third hypothesis. They also comport with previous studies that suggest the influence of religious orientation on Asian American is generally limited to electoral actions (Cherry Reference Cherry2009; Wong et al. Reference Wong, Karthick Ramakrishnan, Lee and Junn2011).Footnote 4

Our final hypothesis is that church political homogeneity will more effectively facilitate a politically salient identity among Asian American churchgoers than church racial homogeneity. To test this, we examine the respective relationships between each of these factors and AAPI respondents' linked fate. Table 6 presents results regressing each form of homogeneity on linked fate. These results support hypothesis 6. There is a positive association between church political homogeneity and linked fate (p = 0.06). In contrast, the relationship between church racial homogeneity and linked fate is null (p = 0.14).

Table 6. Church racial and political homogeneity on Asian American linked fate

Note: OLS regression coefficients. Standard errors are reported in parentheses. *p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

That Asian Americans' reports of racial group linked fate appear to be more strongly linked to their churches' political homogeneity than racial homogeneity may appear counterintuitive. However, this trend is consistent with our account that perceptions of shared ideological views among parishioners can cultivate strong and salient identity ties among Asian Americans. This is a group comprised of a multiplicity of national origins and significant proportions of people still acquiring familiarity with the U.S. racial order. A higher concentration of Asian American parishioners, therefore, should not necessarily translate to either greater adherence to pan-ethnic Asian identity or greater incentive to advance the racial group's interests through political action. In contrast, the perception that other churchgoers share one's political leanings entails the processes of political learning, establishment of shared experiences, and fostering of lateral relationships across parishioners that entail mutual reciprocity and trust. These are all critical elements of Han's (Reference Han2016) relational organizational model of political behavior cultivated through civic institutions. Consistent with this approach, we find the bonding capital forged from the perceptions of political homogeneity within the church augments Asian Americans' sense of racial identity. We also find this homogeneity fostering more voting and electoral participation. The bonding capital forged from the perceptions of shared ideological views is an effective animator of identity and action for Asian Americans.

DISCUSSION

In essence, our findings comport with the scholarship pointing to a more tenuous association between racial group identity and Asian American political behavior. A church's racial composition is less than critical for influencing Asian Americans toward greater participation in politics than the composition of political views held by its members. The unique role of church political homogeneity in influencing political participation among Asian Americans is robust to various model specifications. Yet, we remain cognizant of the challenges and limitations of this research.

One such challenge was to determine whether the influence of church political homogeneity was present across the diverse range of national origin groups comprising the AAPI sample. Running models disaggregated by national origin greatly limited their statistical power. We were left to make confident inferences about the positive effect of political homogeneity on political participation only for Chinese American respondents (the effect is positive and significant at the p < 0.05 level for voting and conventional modes of action). When groups by other national origin are disaggregated, sample sizes range from only about 25 to 110 individuals who report a Christian religious affiliation. Given the sample size issue, future work should seek to examine how the phenomenon revealed here holds across the wide spectrum of Asian Americans' national origin groups.

We also note again that our theoretical account and findings are limited to the political behavior of Asian American Christians. We do not claim that affiliates of more traditionally Eastern religions are not active in politics. We simply recognize that churches operate differently from other religious institutions, with which large numbers of Asian Americans also have contact with one another—such as in temples or mosques (see the work of Bao Reference Bao2015; Chang Reference Chang2010).

We also acknowledge the limits of utilizing cross-sectional survey data to corroborate claims regarding the directionality of the causal arrow between learning that other churchgoers share one's political leanings and motivating one's political behavior. We contend that churches are a site for Asian Americans to learn about the ideological leanings of others, which in turn can cultivate a bonding social capital that can facilitate political action. It is important to note that work by scholars such as Margolis (Reference Margolis2018) argues that individuals can develop meaningful political orientations and practices before they engage in behaviors within their religious institutions. Our current study does not make ironclad empirical claims about the direction of causality between respondents' perceptions of church political homogeneity and their political behavior. Yet, we maintain our account is both intuitive and in line with extant scholarship in positing that Asian Americans—especially due to the large proportion of immigrants among the population—join churches before their habits of political participation in the host system are formed. Asian Americans consequently learn how to translate their involvement in religious institutions toward greater involvement in the political realm. Future work can gain precision on the directional arrow by employing either time series data or experimental designs.

Future research should also seek to address whether or not this bonding form of social capital can also motivate other racial/ethnic minority groups to become more active in politics. Does this phenomenon hold when considering African Americans and Latina/os? Preliminary analysis utilizing the African American and Latina/o samples of the 2016 CMPS show that this bonding social developed in the church is fairly unique to Asian Americans. African Americans who attend a church with other politically like-minded individuals are slightly more likely to take conventional action such as attending political meetings but not more likely to vote or protest. Latina/os attending such religious institutions are not more likely to participate in any mode of political activity. The influence of church political homogeneity may be more unclear when considering Latina/os, given the group's general propensity to identify more with Catholicism than Protestantism. Differences in religious institutional frameworks may have differential spillover consequences for political behavior (Verba, Schlozman, and Brady Reference Verba, Lehman Schlozman and Brady1995; Jones-Correa and Leal Reference Jones-Correa and Leal2001). If the Catholic Church is a bit more hierarchical compared to Protestant churches, bonding social capital might not have as great of a facilitating influence on Latina/o participation relative to groups that generally affiliate as Protestant Christians.

CONCLUSION

Bonding social capital appears to motivate Asian Americans' democratic participation in political affairs; however, not through the mechanism emphasized by previous scholarship. Utilizing a more robust measure and current data set among Asian Americans, we find that church racial homogeneity cannot confidently predict voter turnout. On the contrary, perceptions that one's political views are generally shared by many of one's fellow churchgoers have a strong and positive relationship to a wide range of electoral activities.

Viewing churches as schools of democracy highlights their role in cultivating a community for Asian American congregants, via offering opportunities to engage in substantive interactions on a regular basis. Within the church, Asian Americans can realize their ideological similarities with others. This recognition facilitates the development of mutually reciprocal relationships with fellow parishioners. Politically like-minded individuals then use political participation as an outlet to prove, solidify, and strengthen their reciprocal commitment to their political allies found in the church. We find the bonding social capital cultivated among this minority group on the basis of perceived shared political views explains their higher propensity to take action. We believe future work can also press further by considering the manner in which the content of political messaging within the Asian American church may also work to influence the political participation of congregants.Footnote 5, Footnote 6

Religious orientations had major implications for the 2016 presidential campaign. For instance, vote choice between Trump and Clinton was more polarized along religious orientations compared to previous elections (Smith and Martinez Reference Smith and Martinez2016; Sides, Tesler, and Vavreck Reference Sides, Tesler and Vavreck2019). While much emphasis was placed on how religious affiliation influenced the political decisions of White voters, less attention was paid to this relationship among minority groups such as Asian Americans. Analyzing national survey data collected in the immediate aftermath of the 2016 election, we confirm the contemporary relevance of religion to Asian American politics. As recent work indicates that adherence to a religious identity shapes people of color's politics in manners distinct from Whites (Wong Reference Wong2018), it is all the more paramount to explore the racial variation in how churches socialize and influence their members politically.

The differences within the Asian American population, ranging from national origin to acculturation to language, can pose challenges to the development of pan-ethnic ties among members of the group. Here we have provided a pathway through which Asian Americans can develop politically fruitful bonds on the basis of shared ideological beliefs. This type of bonding social capital, which we demonstrated to be an effective facilitator to Asian Americans' political activity, underscores the important role of the church as a site for incorporation of the group within U.S. politics. Following a wide body of research, we view religion as central to understanding Asian American politics, while highlighting a novel manner in which religious institutions shape the political behavior of the group. By identifying the participation outcomes as a function of this bonding social capital, we uncover the political potential that can be generated from the pews.

Data Access

The 2016 Wave of The Collaborative Multi-Racial Post-Election Survey is embargoed to contributors and their co-authors until 2021. At that time, the data will be made public through The Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research (ICPSR).