Debates about religious symbols in public places and the post-9/11 controversies about the compatibility of Islam and democracy within and beyond Europe indicate a new age of religious diversity and of a major new conflict area in liberal democrcacies.Footnote 1 However, in conventional public policy research, religion has been largely neglected as a relevant factor and with the exception of a few welfare and social policy studies, there is little knowledge and empirical evidence for its policy implications. This is even more astounding in the field of comparative politics of immigration and integration in liberal democracies and the resulting fundamental questions regarding the governance of cultural pluralism, which to a large extent stems from immigration and growing immigrant communities in Western societies (see Bader Reference Bader2007).

This article asks what role religious patterns in general and major churches (both Catholic and Protestant) in particular, play in shaping particular immigration policies. It follows the “family of nations” concept in comparative policy research (Castles Reference Castles1993; Reference Castles1998) and argues that the interplay of nation building, religious traditions, and church-state-relations affect churches' role in the making of immigration policy. The working hypothesis is that the humanitarian mission of Christian churches is often subordinate to national policy concerns and that Catholic churches opt for more restrictive policies than Protestant ones. On particular human rights issues such as asylum, churches may also risk conflict with the state. The following provides some reasoning for this hypothesis.

As Tomas Hammar reminds us, citizenship in the pre-modern past was closely connected to religion and modern citizenship can be seen as one of the results of secularization (Hammar Reference Hammar1990, 49–51). Still, until today, in many countries, national identity and the logic — if not code — of nationality are tied to cultural and in some cases (e.g., Poland, Ireland, Grecce), explicitly religious criteria (see Bruce Reference Bruce2003; Mavrogordatos Reference Mavrogordatos, Madeley and Enyedi2003). In general, therefore, we should expect religious legacies to somehow inform modern concepts of membership in political communities. Also, trajectories of nation-building and patterns of nationhood should play a major role in explaining cross-national variations in immigration policies (see Brubaker Reference Brubaker1992). Hence, one of the central questions of this article is: to what extent does religion, here defined in terms of religious traditions and institutions, affect the politics of immigration, here defined as the regulation of access to territory and citizenship? More specifically, we ask whether particular religious traditions and institutions provide constraints for more liberal immigration and integration policies. For example, a recent study of religious freedom and pluralism in transitional societies in Southern and Eastern Europe found that “holistic visions” of society, as found in Christian Orthodoxy or Islam tend to result in restrictions of minority rights (Anderson Reference Anderson2003, 195f.). In this light, one might hypothesize that cultural heritage in Western democracies (i.e., Catholicism vs. Protestantism) is a significant predictor for variation in immigration and integration policies, especially when closely intertwined with concepts of nationhood, as has been found for other policy areas as well (see Minkenberg Reference Minkenberg2002; Reference Minkenberg, Madeley and Zolt2003a). This, however, needs to be tested in comparison with other dimensions of the religious factor (for example, religiously oriented political parties, degree of secularization, etc.). In general, it is assumed that religion's influence on public policy is culturally path-dependent. Depending on the degree of secularization as “disenchantment” (Weber), one might expect some kind of convergence. However, the confessional legacy is postulated to maintain a policy effect beyond the actual beliefs and practices, and churches' behavior in actual conflicts over immigration and multiculturalism may diverge from the overall cultural path, due to political rather than strictly religious (theological) considerations.

For the analysis in this article, a fundamental distinction is made, following Hammar (Reference Hammar1985, 7–9) between the politics of immigration control, which aims at the selection and admission of foreign citizens, and immigrant policy, which includes aspects of integration and management of cultural pluralism. Another distinction concerns the concentration on policy output, i.e., official governmental policies and legislation, as opposed to policy outcomes, i.e., the implementation of the policies and their societal consequences, for example, immigration rates or (xenophobic) reactions (see Almond and Powell Reference Almond and Powell1978). The group of countries analyzed includes all larger Western democracies with a Latin-Christian religious heritage and stable economic wealth, the time frame concerns immigration policies after the fall of the Berlin wall (see also Minkenberg Reference Minkenberg2002; Reference Minkenberg2004).

IMMIGRATION, PLURALIZATION, AND PUBLIC POLICIES IN THE MODERN WORLD: THE RELEVANCE OF RELIGION

Most comparative public policy literature ignores religious or cultural variables and tends to concentrate instead on the question of whether politics or economics matter (see Nelson Reference Nelson, Goodin and Klingemann1998, 574–77). Three traditions stand out that touch upon religious policy effects. One is the group of modernization theorists who argue that socio-economic modernization brings about a convergence in policy outputs. In this view, religion matters to the degree that its doctrines are reflected in party platforms, or the general difference between Social Democratic and Christian Democratic parties (see Wilensky Reference Wilensky2002). Another group consists of democratic theorists and party researchers who argue it is primarily structures like corporatism, the institutional set-up of democratic regimes, and patterns of party competition, including the role of the religious cleavage, that matter for the output (see Lijphart Reference Lijphart1999). A third group makes the most direct reference to religion as an input factor by grouping countries according to their geographical and/or cultural proximities and arguing that similar outputs are shaped by similarities in these countries' political as well as non-political make-up, including religious traditions (Castles Reference Castles1993; Reference Castles1998; Esping-Andersen Reference Esping-Andersen1990).

Over the last few decades, the importance of “culturally sensitive” policies, i.e., regulatory and symbolic or, more generally, nonmaterial policies as opposed to the typical distributive policies (see Almond and Powell Reference Almond and Powell1978, 283–314), has increased as a result of various trends in Western democracies. They include both socio-economic changes such as urbanization and post-industrialization and socio-cultural changes such as the spread of mass education and the phenomenon of “value change” (see Inglehart Reference Inglehart1997). They signify an era that elsewhere has been characterized as “post-modernity” or as “reflexive modernity,” defined not as an opposite to modernity but an increasingly self-reflecting, self-critical modernity in which cultural orientations, a heightened awareness of crises, the primacy of the Lebenswelt, and the central role of education, language, and communication dominate, in short processes of further individualization, pluralization, and loss of authority (see Beck Reference Beck1986; Inglehart Reference Inglehart1997). In this context, quality of life issues and related policies, such as education policy, gender issues, and other aspects of family policy gain importance. In other words, in the context of “post-modernity,” personal concerns are increasingly public, and thus public policy, concerns (see Castles Reference Castles1998, 248).

Moreover, immigration to Western countries takes on an increasingly salient role, resulting in ongoing cultural and religious pluralization in the receiving countries, and increasing pressures toward political regulation. These processes put religion back on the agenda of both policy makers and policy research. However, rather little empirical research exists that goes beyond the issue of the immigrants' religion, i.e., mostly Islam, and addresses the role of religion more broadly, i.e., the religious (Christian) legacies of Western societies, their interaction with immigrants and their religion (see e.g., Fetzer and Soper Reference Fetzer and Soper2005; Mooney Reference Mooney2006). This is even more surprising given the fact that the issues of immigration and asylum play a prominent part in Christian theology, going back all the way to the Holy Family's flight to Egypt (see Matthew 2: 13–23) or even the Old Testament (Moses 3: 33–4). This topic has also entered Catholic social teaching and plays a very prominent role at least at the European Bishops Conferences (see Table 1).

Table 1. Six Major Themes at Episcopal Conferences, Ranked in Order of Frequency, by Region (1891–1998)

Source: McGoldrick (Reference McGoldrick1998, 26).

While bishops almost all over the world are preoccupied by, among other things, more general human rights issues and humanitarian questions that may (or may not) be related to the domain of immigration and asylum, it is obvious that European bishops also perceive immigration, including labor migration, as a particular concern (see McGoldrick Reference McGoldrick1998, 28). Due to record immigration numbers in the United States in the era after World War II, this concern is now also shared by United States Catholic bishops (see Mooney Reference Mooney2006, 1460). However, there is a dilemma in this position. As is well known, the Catholic Church came to accept human rights as a universal value in the 1960s (Vatican II), but all the same, the Vatican continued to adhere to the principle of national sovereignty. The tension between these two principles was to be resolved by John Paul II when he declared that the inviolability of borders meets its limits in the violation of human rights. In 1963, John XXIII declared in his “Pacem in terris” that nation states are obliged not only to host refugees and immigrants, but also to care for and integrate them (see Christiansen Reference Christiansen1996, 10–12).

More than 40 years after Vatican II and almost 20 years after the end of the Cold War, this concern has acquired extraordinary significance as the pressure on the nation state to address issues of immigration and integration, and the interaction of immigration and religion has gained new urgency and policy-relevance in Western democracies. In Europe, more than anywhere else, many signs have pointed to a receding political impact of organized religion since the 1960s, such as church attendance rates, the number of priests per population, the participation of the young, the knowledge of the faiths (see Bruce Reference Bruce2002; Davie Reference Davie2000). Yet, mostly due to immigration, the pluralization and increasing heterogeneity of the religious map leads to a growing number and intensity of conflicts at the intersection of politics and religion. First, one of the most visible examples is the immigration and growth of non-Christian minorities, in particular, Muslims. They are at the center of current controversies about multiculturalism, integration of ethnic and religious minorities, and transnational identities (see Kastoryano Reference Kastoryano2002). But we must also not overlook those immigrant minorities, which are Christian but of a rather different theological background of Eastern European Orthodoxy or Christianity in the developing countries. Nor should we, third, forget the increasing number of atheists and unaffiliated that also add to the new religious pluralism, and cannot simply be taken as a measure of “secularity” (see Taylor Reference Taylor2007). The data in Table 2 summarize the most important trends in the 19 countries under review.

Table 2. Trends in Religious Pluralism in 19 Western Democracies, ca. 1980–2000 (letters in parenthesis indicate sources)

Sources: (a) Australian Census of 2001 in Cahill et al. (Reference Cahill, Bouma, Dellal and Leahy2004, 46). (b) Bowden (Reference Bowden2005, 32, 94, 404) on the basis of Barrett, Kurian, and Johnson (Reference Barrett, Kurian and Johnson2001). The Protestant group includes independent Christian groups which do not belong to an organized denomination. In some countries such as Australia, Great Britain, Canada, but also Norway and the Netherlands, the size of this group varies between 3% and 4%. In the USA this groups counts ca. 28%, more than 80% of whom are Evangelical Christians, according to survey data (see Wald Reference Wald2003, 161). (c) Census data and other government statistics around 2000 in Weltalmanach (Reference Weltalmanach2004). Estimates by Maréchal and Dassetto (Reference Maréchal, Dassetto, Maréchal, Allievi, Dassetto and Jørgen2003, Tables 1 and 2) for Muslims in various European countries diverge somewhat from Census data, in some countries even significantly (Muslims in France: 7.0%, in Norway 0.5%, in Austria 2.6%, in Switzerland 3.0%). (d) Estimate by Maréchal and Dassetto (Reference Maréchal, Dassetto, Maréchal, Allievi, Dassetto and Jørgen2003, Tables 1 and 2) for the late 1990s (Census data, corrected by expert opinion). (e) For the year 2000 according to Noll (Reference Noll2002, 282f.) (f) According to New Zealand census of 2001 (http://www.stats.govt.nz/people/default.htm, Accessed on February 7, 2006)

* These values indicate the degree of religious fragmentation, measured by 1 – H (Value of the Herfindahl Index): the smaller H, the higher the degree of pluralism. H is defined as the probability that two randomly drawn persons belong to the same religious denomination (Iannaccone Reference Iannaccone1991, 166). Data for ca. 1980 from Chaves and Cann (Reference Chaves and Cann1992, 278), data for ca. 2000 from Alesina et al. (Reference Alesina, Devleeschauwer, Easterly, Kurlat and Wacziarg2003).

Most importantly, in 14 Western democracies, Islam is the third or even second largest religious community (see Table 2). The countries where Islam is second are among those that are traditionally very homogenous in denominational terms, two Lutheran cases in Scandinavia (DK, N), and two Catholic cases (B, F) located in the West of Europe. In Spain, as in Austria, Muslims are on the verge of leaving Protestants behind. Somewhat mirroring this pattern, is the group of Protestant immigrant countries Australia, Canada, and the United States, plus Finland, in which the Orthodox church takes third or second place. Moreover, from around 1980 until around 2000, religious pluralism has increased in all Western democracies, except for Sweden and the United States. In traditional immigration countries such as Australia, Canada, and New Zealand — along with the Netherlands — religious pluralism has increased from an already high level. In other countries like Austria, France, Italy, and Spain — all Catholic — the jump started from a much lower level and has been particularly pronounced, thus challenging the dominant religion and its actor, the Catholic church, as well as the established mechanisms in the relationship between the church and the state in a fundamental way. If it is true, as some argue (e.g., Castles Reference Castles1993; Reference Castles1998; Martin Reference Martin1978; van Kersbergen Reference Van Kersbergen1995), that within Western democracies religious traditions, in particular Catholicism, assume a particular role in shaping politics and policies, hence constituting distinct “families of nations,” we should expect that in these nations the growth of religious pluralism and the increasing weight of Islam will provoke distinct responses by political and religious actors in the field of immigration and multiculturalism.

All these developments push in the same direction: the established institutional and political arrangements to regulate the relationship between religion and politics in the framework of liberal democracies, long seen to have been solved, are challenged fundamentally and require new justifications. Even without 9/11, the multicultural facts of modern Western society raise new (and very old) questions about the political regulation of religion. Accordingly, we see some major shifts in the debate between two groups of Western democracies, the ones with a more or less established church structure, and those with a more or less clear separation between church and state (see Minkenberg Reference Minkenberg, Madeley and Zolt2003a; Reference Minkenberg, Minkenberg and Willems2003b).

In the first group (Great Britain, the Federal Republic of Germany, as well as some Scandinavian countries), we witness increasingly conflictual processes of realigning religion in the public sphere, for example, with regard to the role of religious education (an increasingly controversial topic in Germany), the presence of headscarves, and Christian symbols in the public, the fight for religious freedom for non-Christian churches (e.g., the debate in Great Britain regarding the recognition of Muslim communities and the torn position of the established Church of England, the controversies around Mosque building in Denmark, or the steps toward disestablishment of the state church in Sweden in 2000; see Gustafsson Reference Gustafsson, Madeley and Enyedi2003; Modood Reference Modood1997). But also in the “separationist group” (the United States and France, but Turkey as well), the governance of religion is experiencing increasing pressures from actors who interpret the neutrality and indifference of the state in religious matters as an adoption of particular political positions at the expense of religion. Secularism is seen not as a guarantee for state neutrality and a balance between all religious forces, but as a political program equivalent to a secularist state religion (see Kymlicka and Norman Reference Kymlicka and Norman2000; Wald Reference Wald2003).

Moreover, these developments in various parts of the world are accelerated by and interwoven with economic and cultural globalization processes (see Beyer and Beaman Reference Beyer and Beaman2007; Haynes Reference Haynes1998; Robertson and Garrett Reference Robertson and Garrett1991). The weakening of state institutions and national identities by these processes, which are even more dramatically highlighted by internal conflicts in the developing world, result in an ideological vacuum. This provides an opportunity for religious traditions, or their “re-inventions,” to gel into cores of cultural identities, projects of transnational unities, and of loyalties. It is this scenario where the argument of a “clash of civilization” unfolds its most persuasive power and where processes and policies of immigration redefine the intersection of religion and politics.

THE COMPARATIVE STUDY OF IMMIGRATION POLICIES: TOWARDS AN OPERATIONALIZATION

Some might argue that on a global scale, differences in immigration policies are fading, at least among Western democracies, due to above-mentioned processes of globalization and the emergence of transnational actors and approaches, particularly in the context of European integration and harmonization (see Geddes Reference Geddes, Geddes and Favell1999; Soysal Reference Soysal1994). This would render a comparative analysis among Western states difficult, if not obsolete. But I hold, in this article, despite some processes of convergence and like reactions of Western nations to new waves of immigration, and despite the influence of the European Union (EU) on member states regulations, nation states still remain the principal actors in establishing boundaries of territory and citizenship and controlling access (Hollifield Reference Hollifield1997; Reference Hollifield1998; Joppke Reference Joppke1999; Thränhardt Reference Thränhardt, Thränhardt and Hunger2003). These differences, the argument goes further, are determined not in the least by the religious-political configurations in each nation state and underlying historical path dependencies. So far, only a few projects have attempted to collect in a systematic manner data on immigration and integration policies, or aspects thereof on a large or even worldwide scale, which are useful for such comparisons, such as the “Comparative Citizen Project” (Aleinikoff and Klusmeyer Reference Aleinikoff and Klusmeyer2000; Reference Aleinikoff and Klusmeyer2001; Reference Aleinikoff and Klusmeyer2002; Weil Reference Weil, Conrad and Kocka2001; see also Minkenberg Reference Minkenberg2004).

In order to measure the degree of openness of particular immigration policies and to compare them to other democracies, a scale of immigration policies is constructed based on some criteria and data from the “Comparative Citizenship Project,” and of other literature. Following the distinction between immigration policies and integration policies made above, the emphasis is on the former only, and models of integration and multiculturalism are left out (for this, see Enzinger Reference Enzinger, Koopmans and Statham2000; Hollifield Reference Hollifield1997; see also Minkenberg Reference Minkenberg and d'Appolonia2008). Next to the data collection problem, the selection of relevant criteria for the classification of immigration policies poses another challenge (see Heinelt Reference Heinelt and Heinelt1994, 10f.). As a starting point, the core aspect of any immigration policy rests in the attempt to control access and membership, and this is reflected in most of the comparative literature (see e.g., Cornelius et al. Reference Cornelius, Martin and Hollifield1994). But Hammar (Reference Hammar1985, 9) rightly stresses that immigration policy basically comprises two dimensions, control of admission (from strict to liberal), and guarantees of permanent status (from secure to vulnerable) ( see also Thränhardt Reference Thränhardt, Thränhardt and Hunger2003, 21–7).

This article follows above reasoning and translates it into two basic categories with three values each, ranging from restricted (−1) to open (+1): the logic for the selection of immigrants (from zero-immigration with the possibility of a guest-worker system and/or ethnic quota to a general openness with point system), and the modes of family reunification (from restricted to conditional to easy) (see also Hammar Reference Hammar1985, chap. 9).Footnote 2 The points are given to each country reflecting the dominant mode in the 1990s. In this list, the category of the selection of immigrants is somewhat problematic because of the various dimensions (and exceptions to the rules) involved. For example, ethnic quotas for Germans may look like an equivalent to post-colonial immigration in other countries. But because of the ethnic restriction (however loose in practice) and the underlying ideology of an ethnic people (the logic of a “homecoming”), it is clearly more restricted than a “color-blind” admission of citizens from former or existing colonies. Post-colonial admission policies are therefore rated as in-between an ethnic quota approach and a more open point-system. Moreover, the European dimension, although far from a uniform standard of immigration policies among EU member states, eases some of the restrictions in labor migration as a result of the principle of free movement. Therefore, all other things being equal, EU membership results in an “upgrading” by 0.5 of the rating in the selection category. This does not apply, however, to the family unification category because the EU directive on family unification was issued after the time frame for the selection of data. This is also true for the new German nationality code of 2000, which does not inform the points Germany receives here. This procedure results in a distribution of the 19 countries under consideration from very restricted immigration policies in Switzerland and Finland to very open policies in Australia and Canada. The results are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3. A Scale of Openness of Immigration Policies in Western Democracies (1990s)

Note: The “Openness Scalce” is based on a country's position in two dimensions: the logic for the selection of immigrants (from zero-immigration with the possibility of a guest-worker system and/or ethnic quota to a general openness with point system), and the modes of family reunification (from restricted to easy; for details see appendix in Minkenberg Reference Minkenberg2004).

Sources: author's research based on Joppke (Reference Joppke1999), Thränhardt and Hunger (Reference Thränhardt and Hunger2003), Weil (Reference Weil1991; Reference Weil2002), Winkelmann (Reference Winkelmann and Djajić2001) and others as well as governmental sources (see also Minkenberg Reference Minkenberg2004).

The distribution of countries in Table 3 reflects, by and large, the classification of countries in much of the comparative literature (see e.g., Castles Reference Castles1998; Esping-Andersen Reference Esping-Andersen1990), with the settler countries (Australia, Canada, New Zealand, but also the Netherlands) on one end of the scale, and central and northern European countries on the other. In the middle range, there appears a mix of a Mediterranean type and the British Isles. The following section turns to the question to what extent this distribution of countries can be accounted for by religions factors, in particular, the role of religious legacies and politico-religious actors.

IMMIGRATION POLICIES AND THE RELIGIOUS FACTOR: A CATHOLIC CULTURAL EFFECT?

The introduction of the religious dimension into the analysis will help to decide whether the prominent “family of nations” model is more appropriate than the other approaches in analyzing variations in immigration policy. In this model, Castles (Reference Castles1993; Reference Castles1998) groups countries according to geographical, historical, cultural, and political similarities and establishes four “families of nations” plus one residual category: the English speaking world (UK, Ireland, and North America), Continental Europe, Scandinavia, the Antipodean family (Australia, New Zealand) and the “odd couple” of Switzerland and Japan. He shows that countries in the same group produce similar policy outputs. Moreover, he recognizes that “since religion defines both the cultural appropriateness of beliefs and behavior, religious differences are clearly relevant to policies concerning education and personal conduct” (Castles Reference Castles1998, 53). But these “religious differences” are identified only by a narrow range of variables: Christian Democratic incumbency, Catholicism, and Catholic cultural impact, the last being a dichotomous summary measure of the first two. This operationalization is problematic because Castles groups France, Germany, and Greece, along with Italy and Austria, in the same category of nations with a Catholic cultural impact.

Departing from Castles' approach, religion in this article is not reduced to the confessional heritage or role of Catholic parties. Instead, following the reasoning in the first section of this article, the religious factor is decomposed into a historico-cultural dimension, i.e., the role of confessional patterns, and a socio-cultural dimension of religiosity, as measured in church-going rates, further an institutional dimension of patterns of church-state relations, and finally an actor-oriented dimension of religious parties and movements.

The first step involves the cultural legacy of religion. In order to measure this legacy, two dimensions are considered: the confessional composition of a country that, if at all, is the standard variable of religion's input in comparative public policy research, and the level of religiosity as a measure of a country's “embeddedness” in religious practice (see Bruce Reference Bruce2000, 3). In terms of the secularization argument, the first might be seen as an indicator of a country's cultural “differentiation,” or cultural pluralism, whereas the second points to the country's path of secularization as “disenchantment.” Most texts that emphasize the role of confessional patterns in a nation's history classify countries as Catholic, Protestant, or confessionally mixed, and most of them, as well as some of the public policy literature (see above), assert a long-lasting influence of these cultural patterns on current policy and politics (see Bruce Reference Bruce1996; Inglehart Reference Inglehart1997; Inglehart and Baker Reference Inglehart and Baker2000; Martin Reference Martin1978). Following David Martin and his distinction between “crucial events” (such as the success or failure of the Reformation and the outcome of civil wars and revolutions) on the one hand, and “resultant patterns” on the other (e.g., the British, American, Russian, Calvinist, and Lutheran patterns), three categories will be used for the countries under consideration: (1) cultures with a Protestant dominance, resulting either from a lack of Catholics (the Scandinavian countries) or because Catholic minorities arrived after the pattern had been set (England, the United States); (2) cultures with a Protestant majority and substantial Catholic minorities according to the historic ratio of 60–40 (the Netherlands, Germany, Switzerland)Footnote 3 where a cultural rather than a mere political bipolarity has emerged along with subcultural segregation; (3) cultures with a Catholic dominance and democratic regimes (France, Italy, Belgium, Austria, Ireland) that are characterized by large political and social fissures, organic opposition, and secularist dogmas (119).Footnote 4

The second component of the cultural legacy is the actual degree of attachment to established religion. This is important because high levels of religiosity assure churches high legitimacy as political actors. Moreover, religiosity may be a better predictor for public policy than confessional composition alone, if the question whether a country is Catholic or Protestant is held to be less important than whether Catholics or Protestants actually attend church, or believe the teachings of the church. In this analysis, religiosity is measured by frequency of church-going rather than by religious beliefs, because it ties religiosity to existing institutions instead of more abstract religious concepts and values. Data on church-going in the 19 countries analyzed here are taken from the 1980s and 1990s waves of the World Values Survey (see Inglehart and Baker Reference Inglehart and Baker2000; Inglehart and Minkenberg Reference Inglehart, Minkenberg, Meyer, Minkenberg and Ostner2000). The data for the 1980s and 1990s are then averaged and the countries are grouped according to the frequency of church-going with ranging from low (less than 20% who go at least once a month), to medium (20–40%), to high (above 40%) (see Minkenberg Reference Minkenberg2002, 238).

The relationship between the religious legacies of the 19 countries and their immigration policies is presented in Table 4. The overall picture is far from clear. Neither confessions nor church-going rates correlate with the degree of openness of the countries' immigration policies. There is a “Catholic effect” in that none of the Catholic countries has implemented an open immigration policy. This is significant because this effect cannot be reduced to the difference between (Catholic) Europe and Protestant non-European countries: the group of countries with an open immigration policy consists of a mix of classical (non-European) and new (European) immigration countries. The suggestion to identify a special Southern or “Mediterranean” type of countries with regard to their public policies (see Baldwin-Edwards Reference Baldwin-Edwards1992; Castles Reference Castles1998, 8f) is somewhat supported by the distribution in Table 4 with the group of Mediterranean countries (France and Italy, Portugal and Spain) clustering in the category of moderate immigration policies. But in part, there is a misconception that results from mixing up immigration trends and immigration policies.

Table 4. Religious Legacy: Confessions, Religiosity, and Immigration Policies

Note: Countries in bold are those with high religiosity; countries in italics with low religiosity.

While Mediterranean countries share the common fate of being late-comers as receiving countries, their approach to controlling immigration is shared by other, non-Mediterranean countries as well (Belgium, Great Britain). Our analysis suggests that what this group has in common is their religiosity, not their geography. This is also true with regard to the growing proportion of Muslims in these countries. Among the four countries where Islam is the second religion (see Table 1), two employ a restrictive immigration policy (Denmark, Norway) whereas the other two, with significantly larger Muslim communities, employ a moderate immigration policy (Belgium, France). Catholicism, even though its doctrine of society is more “holistic” than Protestantism, does not lend itself to a closing of the doors, even in the face of a large and growing non-Christian minority (see also below).

Some other patterns stand out in Table 4, as well. With the exception of Great Britain, the two Protestant groups divide up into opposite camps of immigration policies. As the Scandinavian group demonstrates (with the exception of Sweden), secularization does not result in a more liberal immigration policy, although a declining significance of established churches might facilitate a country's departure from its exclusionist traditions, and its dealing with increasing cultural diversity. Generally, church-going rates seem less telling than confessional legacies when it comes to immigration policies. In the welfare state debate, it has been argued that Protestant countries need to be distinguished according to the type of Protestantism that dominates: Lutheran or Reformed/free church Protestantism. The more encompassing and egalitarian welfare regime have been introduced in Lutheran Protestant countries whereas those where Reformed Protestantism or Calvinism dominated, welfare systems were introduced later and emphasized individualism and a restrained role of the state (see Manow Reference Manow2002). This distinction can help explain that the Lutheran Protestant countries share a restricted immigration policy despite diverging rates of immigration flows in Denmark and Norway/Finland although it does not explain why Sweden has strayed all the way into the opposite camp, as it does not explain why Switzerland and the Netherlands diverge with regard to immigration policies.

Hence, when looking for a common religious denominator for the group with open immigration policies, one must go beyond confessional legacies and church-going rates. As some analyses suggest (see Fetzer and Soper Reference Fetzer and Soper2005; Minkenberg Reference Minkenberg2002; Reference Minkenberg, Madeley and Zolt2003a; Monsma and Soper Reference Monsma and Soper1997), the regime of church-state relations can also claim a certain explanatory power for variations in particular public policies. This institutional dimension of religious legacies is measured by the degree of deregulation of churches in financial, political and legal respects, and applies a six-point scale as developed by Chaves and Cann (Reference Chaves and Cann1992). In a critique of the supply-siders' market-based argumentation, they argue with de Tocqueville that the theoretical focus of state-church relations needs to be adjusted toward political aspects: “Like Smith, [de Tocqueville] focused on the separation of church and state, but he highlighted the political rather than the economic aspect of that separation: the advantage that religion enjoys when it is not identified with a particular set of political interests” (Chaves and Cann Reference Chaves and Cann1992, 275; emphasis in original). Moreover, regardless of the official relationship between church and state, Catholic societies are almost by definition much less pluralistic in religious terms than Protestant societies. But as the data in Table 1 demonstrate, this historical inequality is already in the process of revision.

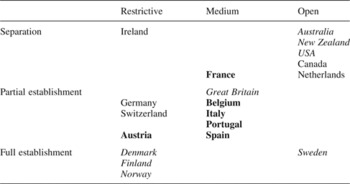

For the purpose of the analysis here, the church-state scale is operationalized by eight indicators covering political, legal, and financial dimensions and summarized into a three-fold typology: countries with full establishment (such as the Scandinavian countries), countries with partial establishment (such as Germany but also Italy and Great Britain), and countries with a clear separation of church and state (such as the United States and France) (for details see Minkenberg Reference Minkenberg, Madeley and Zolt2003a; Reference Minkenberg, Minkenberg and Willems2003b).

Table 5 shows that more so than in the case of Catholicism or secularization (as disenchantment), institutional differentiation of church and state corresponds rather clearly with the type of immigration policy. That is, the more state and church are separated, the more open the immigration policy. The two outliers are Ireland and Sweden. In the former, the separation of church and state corresponds with a high societal relevance of Catholicism that counters — so far — the effects of differentiation. In the latter, a disestablishment process has set in the late 1990s in part as a response to increasing immigration (see Gustafsson Reference Gustafsson, Madeley and Enyedi2003). Another deviating case is France, which is, however, closer to the country group with open immigration policies than to the opposite group (see Table 3). More specifically and discounting the Swedish exception, the pattern is that non-Lutheran Protestantism, in conjunction with a separationist regime, correlates with open immigration policies. This finding points to the particular role of path-dependencies and the interrelationship between a nation's political and religious histories.

Table 5. Church-State Relations and Immigration Policies

Note: Countries in bold are Catholic, countries in italics are predominantly Protestant countries.

There exists a close relationship between the histories of nation-building, democratization, and the respective religious (confessional) histories and church-state regimes. The patterns in Tables 4 and 5 indicate a close link between processes of nation-building and secularization on the one hand, and the respective dominance of Lutheranism, Calvinism, Anglicanism, and Catholicism on the other. With the exception of the Netherlands with its particular Calvinist trajectory, all countries in the upper right field are former British colonies and countries of immigration. As such, they are characterized by an early plurality of religions and a separationist model of church-state relations in distinct opposition to their former “mother country” Great Britain, and its traditional Anglican state church. The Australian history is a case in point. When the country was faced with an increasing denominational pluralization, the initial adoption of the British model of establishment gave way to the American model of separation. This took place already during colonial times, initiated by the New South Wales Church Act of 1836 and was completed, by and large, at the end of the 19th century (see Bouma Reference Bouma2006; Breward Reference Breward2001). Put differently: in the course of the process of these countries' separation from Great Britain, nation-building was intertwined with the process of separating church and state, while keeping the Westminster model of parliamentary democracy. In contrast to this pattern, the Scandinavian countries experienced nation-building along with parliamentarization, and maintenance of the Lutheran state church model (see von Beyme Reference Von Beyme1999, chap 2).

Again, this finding points at the necessity to modify the “family of nations” concept proposed by Castles. While there is some support for the existence of a Scandinavian family even in terms of immigration policies, the other groups break up. With regard to this policy area, the Catholic family shrinks to a core group excluding the bi-confessional countries Germany, Switzerland, and Netherlands. Along with Austria, these countries constitute a type of democracy — labeled “consensus democracies” by Lijjphart (1999) as opposed to the Westminster or majoritarian model — in which early historical conflicts between confessions resulted in a particular emphasis on consensus in decision-making in order to integrate different groups, mostly religious or lingual, into the political process. As the cases of Switzerland and the Netherlands show, doctrinal similarities — here the historical dominance of Reformed Protestantism and Calvinism — recede in the face of divergent processes of nation-building and post-colonialism, they do not play the same role as in the area of social policies (see above). Also, the English speaking family disintegrates into various groups along mostly religious lines. On the one hand, there are the British Isles with a higher level of religious homogeneity and the historically very close association between the major or established church and the nation; here we find a moderate immigration policy. On the other hand, the former British colonies or settler countries are united in their open immigration policies, as they are by their early separation of church and state and high levels of religious pluralism (with a current pluralism value larger than 0.70, see Table 1).

CHRISTIAN PARTIES: A CATHOLIC POLITICAL EFFECT?

The final step in the analysis of religious factors in variation of immigration policies concerns the role of religiously oriented parties. In analogy to the studies of strong left-wing parties and generous welfare states, one might expect a relationship between the presence of these parties and a restrictive output in immigration policies. In fact, the most direct link between religion and politics at the intersection of the electoral and policy-making levels exists where explicitly religious parties, most notably Christian Democratic ones, play a role in the party system. Moreover, the relevance of religious cleavages in the contemporary Western world has been demonstrated by a variety of election studies. While the class cleavage has undergone a steady decline in significance, the religious cleavage in terms of the relationship between religiosity (as measured by church attendance) and voting behavior has stayed rather stable. In the United States, there was even a slight but steady increase of religious voting, which can be attributed to the growing mobilization efforts of the New Christian Right (see Dalton Reference Dalton1996, 176–85; see also Inglehart Reference Inglehart1997; Minkenberg Reference Minkenberg1990).

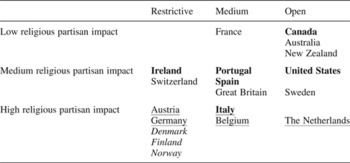

Instead of focusing on classical Christian Democratic parties alone, I recognize the variety of the confessional party landscape with at least four versions of Christian parties in Western democracies after World War II: political Catholicism in homogeneously Catholic countries with a high level of system support (Austria, Belgium); political Catholicism in mixed confessional countries representing Catholic minorities and exhibiting initially — low levels of system support (Germany, the Netherland, Switzerland); the special case of Italy where 99% of the population is Catholic, yet Catholics feel suppressed; Protestant Christian parties in predominantly Lutheran Scandinavia (Denmark, Finland, Norway, Sweden). In the four non-European democracies, specifically Christian parties did not emerge (see von Beyme Reference Von Beyme1984, 121–27; see also Hanley Reference Hanley, Minkenberg and Willems2003; Whyte Reference Whyte1981). In order to arrive at a measure that captures a Christian party impact, the 19 countries are classified according to the role of religion in these parties' identity and program, their relationship to religious groups, the salience of the religious cleavage in voting behavior, and the length of these parties' participation in national governments (for details see Minkenberg Reference Minkenberg2002). The resulting six-points-scale was summarized in three categories, ranging from low to medium to high religious impact (see Table 6). This categorization shows a striking similarity between the ranking of these nations and the ranking of the salience of religious voting, with the Netherlands, Belgium, and Denmark at the top, the United Kingdom, Canada and the United States at the bottom of the scale. There is an obvious relationship between the cleavage factor on the voters' side (see Dalton Reference Dalton1996, 185) and these parties' orientation at the party system and government side. It also shows that with regard to the partisan variable, these countries cannot be ranked according to their confessional composition.Footnote 5

Table 6. Immigration Policies, Religious Partisan Impact, and Religiosity

Note: Countries in bold are those with a high level of religiosity; countries in italics are those with a low religiosity. Countries that are underlined are those with strong Christian Democratic elements in the party system.

Table 6 depicts an interesting role of these parties. What has been shown with regard to other social policies (see Minkenberg Reference Minkenberg, Minkenberg and Willems2003b; van Kersbergen Reference Van Kersbergen1995), i.e., that a strong Christian Democracy corresponds with a moderate abortion ruling and family policies, and reflects a particular policy profile of Christian Democracy in association with a larger and distinct vision of society, disappears. Instead, a more general correlation occurs: again with a notable exception (here: the Netherlands), the higher the religious partisan impact, the more restrictive the immigration regimes.

Interestingly, the group with strong Christian Democratic parties spreads across the scale of immigration policies, and again, the Scandinavian group (without Sweden) stands out as a distinct type of country also with regard to religious partisan impact. In these countries, as in Germany and Austria, the traditional concept of a homogeneous nation seemed to have informed also party politics, especially on the political right. This is not the case with the Netherlands and their Christian Democrats, who unlike their Eastern neighbor faced a history of post-colonial immigration and subscribed to a view of Dutch culture, which was less determined by notions of ethnicity and closeness (see Koopmans et al. Reference Koopmans, Statham, Giugni and Passy2005; van Amersfoort and van Niekerk Reference Van Amersfoort, van Niekerk, Thränhardt and Hunger2003).

So far, the particular involvement of churches as actors in the immigration policy field has been ignored due to the rather structural approach in the comparative analysis presented here. As a complement to this analysis, the final section turns to the positions and policy relevance of churches in a more case oriented design. The question to be answered is: do churches' activities in the field of immigration policies fall in line with the patterns outlined above or do national policy concerns or traditions outweigh the churches' effort to shape the policies? And are there notable differences between the Catholic Church and Protestant churches? These questions shall be addressed with a closer look at the country cases of the United States, Great Britain, France, and Germany.

CASE STUDIES: CHURCHES IN THE STRUGGLE OVER IMMIGRATION POLICIES

In the United States, the Catholic church has a long history of engaging on behalf of immigrants and refuges, not in the least because the church immigrated into the country with a large quantity of Catholic immigrants: “immigration and American Catholicism present an inseparable relationship” (Gillis Reference Gillis, Yazbeck Haddad, Smith and Esposito2003, 35). Whereas in the first half of the 20th century, the bulk of Catholic immigrants came from Europe, nowadays this group stems largely from Central and Latin America. Since the 1940s, the church therefore has established lobby activities in Washington, DC through the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB) and the national office of Migration and Refugee Services (MRS) (see Mooney Reference Mooney2006, 1461; also Gimpel and Edwards Reference Gimpel and Edwards1999). Interestingly, whereas in social, family, and educational issues, the Catholic church is much closer to the Republicans than to the Democrats, it finds more in common with the Democrats when it comes to immigration issues and it also is able to form cross-party coalitions in this policy field. When in 1996, Democrats and Republicans were deeply divided over the reform of the illegal and legal immigration (H.R. 2202), a USCCB lobbyist managed to bring together Democratic and Republican representatives, and to work out a compromise by separating the issues of legal and illegal immigration in the bill (see Mooney Reference Mooney2006, 255; see also Wong Reference Wong2006, 138). In general, the position of the Catholic church and its affiliates such as the Catholic Legal Immigration Network (or CLINIC, established 1988) on issues of immigration are primarily directed at immigrants that are already in the country and need financial, legal, educational, and other support (see Burdick and Chenoweth Reference Burdick and Chenoweth2007, ii). CLINIC criticizes the current immigration policy as outdated. With other Catholic organizations as well as non-Catholic religious organizations, in the Interfaith Statement in Support of Comprehensive Immigration Reform, they pledge for an easing of the naturalization procedure, a shortening of waiting periods in family reunifications, the introduction of a guest worker program that allows better access to the labor market, and more federal money for the counsel of immigrants (Burdick and Chenoweth Reference Burdick and Chenoweth2007, vii–x; World Relief 2005). Similar demands can be found in policy positions of the MRS (see Mooney Reference Mooney2006, 1462). In some cases, representatives of the Catholic Church go beyond lobbing activities. When in 2006 a bill was introduced in Congress that declared any assistance to illegal immigrants as a federal crime (H.R. 4437), Los Angeles Bishop Roger Mahony called upon Catholic Priests “to disobey [the] proposed law that would subject [catholic priests], as well as other church and humanitarian workers, to criminal penalties” should the law be enacted (Mahony Reference Mahony2006; see also Fetzer Reference Fetzer2006).

On the non-Catholic side, the Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Service, also a signatory of the Interfaith Statement on immigration reform of 2005, is one of the largest Protestant organizations directed at immigration but outside the Midwest where many voters belong to the Lutheran church, its influence seems limited and it usually joins pro-immigration coalitions to pressure policy makers (see Gimpel and Edwards Reference Gimpel and Edwards1999, 52). In the camp of Protestant fundamentalism, a split has emerged over immigration between those who advocate a more open immigration policy and those who are in favor of a more restricted approach. This split can be detected in the National Association of Evangelicals, which in 1995 issued a statement addressing immigrants' concerns in general, asking government officials “to maintain reasonable and just admission policies for refugees and immigrants” while by 2000, their declarations were directed only at refugees (National Association of Evangelicals 1995; 2000). Also NAE did not sign the 2005 Interfaith Statement on immigration reform; only a branch of NAE did (see Cooperman Reference Cooperman2006).

Overall, church activities in the field of immigration policy in the United States fall in line with the general national pattern of an open immigration policy. Whereas among Protestant fundamentalists, a significant current seems to turn toward a more restrictive approach, both Lutherans and Catholics are found siding with those who criticize current policies and advocate an even more open policy — to the point of calling for civil disobedience if laws violate church representatives' sense of fairness.

In the British case, the Church of England has direct policy relevance due to the two archbishops' and 24 diocesan bishops' seats in the House of Lords. In addition, the Church has established in 1970 a Board for Social Responsibility, which is a major advisory body for the Church's general synod, which makes the Board the Church's prime instrument to place its positions on immigration and integration before the public (see Ecclestone Reference Ecclestone and Moyser1985, 111). Following its traditional and biblically based responsibility for immigrants, asylum seekers and refugees, one of the Church's primary concerns for public advocacy is the situation of asylum seekers in Great Britain, and the fight against misperceptions of this situation (Church of England, Mission and Public Affairs Council 2005). On the other hand, the Church refrains from attempting to directly influence British immigration policy. Its criticism of political officials' language relating to immigrants and its letter to the parliamentary parties in October 2000 was meant to fight discriminatory remarks in political rhetoric rather than a comment on current policies of immigration (Church of England 2000). When the Church issues statements on immigration policy, it is usually at the invitation of policy makers, as was the case in February 2002 when the Home Secretary asked for a contribution to the White Paper “Secure Borders, Safe Haven — Integration with Diversity in Modern Britain” or the bishops' positive feedback in the House of Lords to the Home Secretary's proposal for a reform of immigration and refugee policies (see Church of England, Board for Social Responsibility 2002, 6; Church of England 2001). In specific policy issues such as naturalization procedures and asylum, the Church usually advocates a more liberal rather than a restrictive approach. Overall, the British case demonstrates the state church's typical restraint in the field of policy making (see also Minkenberg Reference Minkenberg, Minkenberg and Willems2003b).

The two large German churches have been active in immigration and integration issues for several decades. Their primary concern in the field of immigration policy is with charity issues but they also participate in public debates. Interestingly, both churches collaborate in the forming of public statements and activities, such as the “week of the foreign co-citizens” that had been inaugurated by the Evangelical Church of Germany (EKD) in 1975, but is carried today by both churches. There are also numerous joint statements by the Council of the EKD and the German Bishops' Conference of the Catholic Church. In 1993, they established an ecumenical working group on migration issues that makes it hard to identify a distinct Protestant or Catholic involvement in immigration policy (see Rat der EKD et al. Reference Rat der1998: para. 97).

The existence of a strong Christian Democracy in Germany (see Table 6) suggests a particular closeness of the Christian churches to party politics and policy making. While that may have been the case in the foundational era of the Federal Republic (see Minkenberg Reference Minkenberg, Minkenberg and Willems2003b), there is a puzzling distance between Christian Democrats and Christian churches particularly on immigration issues (see Sandersfeld Reference Sandersfeld2002, 492). In the debate about the new immigration law in the early years of the Schröder government, the Catholic Church insisted on bringing into congruence the new law and the principles of fundamental Christian values of solidarity and human rights. However, the Christian Democrats emphasized the need to limit significantly the level of immigration, already low in international comparison (Sandersfeld Reference Sandersfeld2002, 493; see also Minkenberg Reference Minkenberg, Kitschelt and Streeck2003c). The largest difference emerged with regard to the issue of family reunification that was strongly advocated by the Catholic church whereas the CDU and the CSU asked for a particularly rigid handling. It is also noteworthy that the Christian Democrats asked not to invite the churches and other interest groups to the hearing of the parliamentary committee on the reform of the nationality code in April 1999; the churches participated in these hearings nonetheless due to the invitation by the Greens (see Barwig Reference Barwig1999, 347). There are several instances when the German churches tried to influence immigration policy making in the 1990s, the most noteworthy of which is the reform of the asylum law in 1993, when the right to asylum was severely restricted and the churches formulated minimal standards to protect asylum seekers (e.g., an open access to the territory of the Federal Republic and an effective protection against deportation) — with little success (see Rat der EKD et al. Reference Rat der1998, para. 172).Footnote 6

In specific policy areas, the churches often produced positions that were more pro-immigrant than those of the CDU/CSU, for example, the acceptance of the principle of “ius soli” in the new nationality code of 2000 and of dual citizenship (Rat der EKD et al. Reference Rat der1998: para. 174) and the call for an easing of the rigid stipulations of the family reunification regulation for admitted refugees in the foreigners law (see Huber Reference Huber2001; see also Kock Reference Kock2001). In asylum issues, the churches have been at odds with government policies in the 1990s when they occasionally provided shelter for asylum seekers who were not admitted by the courts according to the new asylum law, the so-called “church asylum” (“Kirchenasyl”). In fact, when they did so, they violated the law in the name of Christian charity, not unlike the American Catholic bishop who called for acts of civil disobedience by church officials in case an unfair law was to be enacted (see above).

The Catholic Church in France has also participated vividly in the immigration debates since 1946 by calling on political officials as well as the general public to take seriously their responsibility toward immigrants (see Costes Reference Costes1988). At times, the church asks the general public to resist unfair immigration policies with civil disobedience (see Gaulmyn Reference Gaulmyn2004). Several authors testify that the Catholic Church has experienced declining rates of church-going and church membership notwithstanding, a specific moral role in the context of immigration debates (see Mooney Reference Mooney2006, 1460). After all, Catholic Charities in France has a wide network at the grassroots level in the entire country and receives more than one million immigrant clients annually who, Catholic or not, approach the church rather than the state because of their precarious legal status (Mooney Reference Mooney2006, 1464). Officially, church officials such as Bishop Brunin, the chair of the Comité épiscopal des migrations et des gens du voyage, reject however the idea that the Church should be directly involved in law-making or unmaking (see Gaulmyn Reference Gaulmyn2004).

A particular moment of church activity occurred in the spring of 1993 when hard-line Gaullist Minister of Interior Charles Pasqua pushed for a reform of the immigration law that was intended to curtail the social and civil rights of foreigners, labor migrants, and asylum seekers (in part modeled after the Californian Proposition 187) and a more restrictive nationality code (the so-called “lois Pasqua”). These measures were heavily criticized by the church and its official, Bishop Pierre Jatton who at the time was president of the Commission épiscopale des migrations. He issued an open letter declaring his solidarity with the migrants in France who in his view were instrumentalized as scapegoats for all the ills in French society (see Mallmann Reference Mallmann2004). Hearings were postponed to give the Catholic as well as the Protestant churches a chance to be heard, and meetings were arranged between the Minister of Justice and representatives of the churches (L'Humanité, June 2, 1993). The law however, went into effect at the end of 1993, only to be revoked partially by the Constitutional Council.Footnote 7

On the other hand, the church displayed a more ambiguous position when it came to the issue of “church asylum,” i.e., the squatting of churches by asylum seekers facing deportation. One such incidence occurred in the Parisian church St. Ambroise when 300 Africans sought shelter in the church in the absence of the priest (L'Humanité, April 24, 1996). While humanitarian and charity organizations supported the asylum seekers, the priest of the parish when notified asked the police to clear the church, thus triggering a protest wave against the Catholic Church. A similar event happened in June 1996 in another church involving 228 Africans. Here the priest, who also wanted the church to be cleared by police, was persuaded by his superiors to refrain from such a measure.

More recently, at a bishops conference on the asylum law in February 2002 the presidents of the three church-related organizations Comité Episcopal des Migrations, the Commission sociale de l'Episcopat and of Justice et Paix, affirmed the biblical foundations of the right to asylum and appealed to the political class to improve the conditions of asylum seekers (in particular, to shorten the waiting period, and to allow them to work while their application was processed) (Conférence des évêques de France, Commission sociale des Evêques 2002). However, this position was undermined when in September of the same year, the bishops criticized in a public declaration the practice of church squatting, and argued that these activities ran counter to the interests of illegal immigrants (Buos Reference Buos2004). In 2004, this inconsistency led the bishop's conference to issue a statement in which they reminded the faithful of their obligation to defend human dignity and in which the bishops accepted an “occasional legitimation” of civil disobedience in cases when the law fails to protect the human person (Buos Reference Buos2004). The Chirac government and its minister of interior Sarkozy met with repeated criticism by the churches in its increasingly hard-line approach toward illegal immigration and asylum seekers (see Tassel Reference Tassel2006).

In sum, these cases demonstrate that in general, the churches add critical voices in the respective countries' immigration debate and are usually to be found on the pro-immigration side vis-à-vis their national governments or party allies (such as the CDU/CSU in Germany). Hence, while long-lasting religious traditions may have informed national policy approaches or established some cultural path dependencies, in the actual debates and struggles over immigration policies, churches — with the exception of the Protestant fundamentalists in the United States — push for a more open regime than the official government policies. It is particularly noteworthy, that the three Catholic churches under consideration all explicitly (in the United States and in France) or implicitly (in Germany) call for or even manifest acts of civil disobedience in the face of laws or policies that are considered blatantly unjust. This has not been observed in the Protestant camp in these countries and reflects a greater distance between Catholic churches and state power compared to Protestant churches in Europe which have historically been tied to the respective nation state.

CONCLUSIONS

Western democracies are undergoing a process of extraordinary religious and cultural pluralization that is largely a result of an intensified immigration over the last decades. Immigration policies shape these processes, as they are in turn shaped not only by socio-economic and political factors but also by religious factors. Religion as a policy factor can be identified as the respective Christian legacies of these countries and the role of the major churches and religious communities in the political process. In this vein, this article analyzed in a structural and an actor-oriented perspective, the way in which religion affects the immigration policies in 19 Western democracies.

I have argued that despite some convergence of Western nations in their policies and reactions to the challenges of globalization and immigration, nation states still remain the principal actors in establishing boundaries of territory and citizenship and controlling access. These differences, the argument goes further, are determined not in the least by the religious-political configurations in each nation state and underlying historical path dependencies. Adding the religious factor to the analysis of immigration can shed some light on cross-country diversities and patterns in this policy field. The differences are not only due to the particular welfare regimes in these countries or to their economies, but also to the religious, or more precisely Christian heritage. This heritage, however, needs to be disentangled, as it makes a difference whether countries are impregnated with particular strands of Protestantism (Lutheranism, Anglicanism, and Reformism) or Catholicism, whether there was an early or late decline of attachment to the major religious traditions and institutions, whether there exists a separationist regime of state-church relations or an established state or national church. In the course of all these countries' political histories, nation-building and democratization processes were intertwined with these particular religious histories, where national identities were closely related to established or dominant churches, as in the case of Scandinavia and the British Isles among the Protestant countries, and in the Mediterranean countries in the Catholic camp. Outside Europe, the former British colonies' nation-building was accompanied by the process of separating church and state while keeping the Westminster model of parliamentary democracy, with the exception of the United States. Early on, these nations as settler colonies and immigration countries have exhibited a high level of religious and cultural pluralism, and still today are the most pluralistic in the Western world.

Against this backdrop, the article's findings point to the necessity to modify the “family of nations” concept as developed by Francis Castles (Reference Castles1993; Reference Castles1998). While there is sufficient evidence for the existence of a Scandinavian family in the domain of immigration policies (as in many others), the other groups break up. The Catholic family is reduced to a core group that excludes the traditional bi-confessional countries (Germany, Switzerland, the Netherlands). Along with Austria, these countries constitute “consensus democracies” (Lijphart Reference Lijphart1999) in which deep-seated confessional conflicts resulted in a consensual mode of decision-making in order to prevent the exclusion of different, mostly religious groups. As the cases of Switzerland and the Netherlands with immigration policies at opposite ends of the spectrum show, doctrinal similarities (Reformed Protestantism) recede in the face of divergent processes of nation-building and post-colonialism; in contrast to their parallel effects in the establishment of social policies (see Manow Reference Manow2002). The English speaking family disintegrates as well, with the British Isles exhibiting a moderately open immigration policy on the one hand, and the former British colonies or settler countries, being united in their open immigration policies, on the other. These are joined by the Netherlands and Sweden with very few similarities to the settler countries but a similarly strong tradition of tolerance toward difference. Moreover, the uniformity of Christian Democracy as a party family with a distinctive approach to public policies (see van Kersbergen Reference Van Kersbergen1995) dissolves as well in the realm of immigration policies. These parties' effect seemed to be superseded by the countries' national cultural traditions (Catholicism or varieties of Protestantism, state-church separation or establishment).

Finally, I have shown that with regard to immigration policies, the major churches in these countries deserve a closer look on their own. They are not only, or not any more, the “natural allies” of Christian Democracy or other religious parties. Their role in some countries' more recent immigration debates and policies demonstrates a disjuncture between the countries' general patterns of religious traditions and immigration policies on the one hand, and the actual policy positions and effects of churches on the other (see Mooney Reference Mooney2006). Catholic churches seem to develop a rather critical distance to national policy makers to the point that they advocate occasional civil disobedience in cases of unjust policies. Here, state-church regimes provide effective opportunity structures. In the two countries under consideration, where there is a rather strict separation of church and state, i.e., the United States and France, the Catholic churches are the most critical of government policies. In Great Britain and in Germany, where there is a traditional intimacy between church and state, the churches are more reluctant to criticize government openly but even in Germany, the cases of church asylum in the 1990s demonstrate an occasional willingness to undermine the state's authority in asylum matters. The humanitarian mission of churches and its policy implication is mediated by the historical pattern of a country's church-state relationship.