Prior to the 2016 election, New York magazine claimed that, “the most powerful voter this year, who in her rapidly increasing numbers has become an entirely new citizen is the Single American woman” (Traister Reference Traister2016). Together, pundits and Democratic activists focused on these women because their numbers were large and growing. As of 2016, 59 million single women (i.e., defined as women who never married or who were divorced, separated, or widowed, regardless of parental status) accounted for 24% of eligible voters (US Census 2017; Voter Participation Center 2018). Their numbers were also rapidly increasing. As The Voter Participation Center (2018) noted, “Between 2000 and 2014, the number of unmarried women in the United States increased by over 12 million.” Though pundits and activists acknowledged that single women vote at lower rates than their married counterparts, they focused on single women because they believed that single women had the potential to change American policy and politics (Traister Reference Traister2016; The Voter Participation Center 2018). For example, they posited that single women, who generally face higher levels of economic instability than married women do, would lead the charge for a new progressive agenda focused on equal pay, paid family leave, increasing the minimum wage, universal pre-K, affordable college education, affordable healthcare, and broadly accessible reproductive rights and that their increasing numbers meant that they could provide crucial margins of victory in elections if they could just be convinced to turn out to vote (Traister Reference Traister2016; The Voter Participation Center 2018). Despite this enthusiasm, the new single women's constituency did not materialize as predicted in 2016: only 53.1% of them voted, compared to 70.0% of their married counterparts (Current Population Survey [CPS] 2017e).

Single women's comparatively low turnout rates raise questions about why they are not a large, active, and powerful political constituency. One possibility is that although Democratic activists and pundits are enthusiastic about single women, they simply assume that large numbers of them will flock to support progressive organizations, causes, and candidates even if they do not explicitly lobby for them during policy debates. In this article, I examine whether women's organizations explicitly advocate for single women, during debates about women's interests when they submit comments to government agencies during the rule-making process. How often do they discuss single women explicitly, and which single women do they focus on?

To answer these questions and to determine how effectively women's organizations represent this developing constituency, this article provides one of the first systematic examinations of whether and how women's organizations represent single women when they lobby federal level policy makers. For this analysis, I rely on an original dataset of 1,021 comments that women's organizations submitted to federal agencies during the rule-making process between 2007 and 2013 to answer three questions about how women's organizations represent single women during rule making. First, how often do women's organizations explicitly refer to single women in the comments they submit to rule makers? Second, how often do they discuss the diversity of single women's experiences, and which types of single women do they discuss the most often? Third, are women's organizations more likely to explicitly focus on single women in some policy-making contexts rather than others?

As I answer these questions, I expect to find that women's organizations only rarely refer to single women and the diversity of their experiences due to their long history of advocating on behalf of mothers (who they often assume are married), pressures posed by policy feedback and the gendered assumptions built into many American welfare state programs, and a desire to avoid being seen as advocates for single women, a group that has traditionally been negatively stereotyped and stigmatized in American politics. On the rare occasions that they do mention single women, I expect that women's organizations will only address their concerns in policy-making contexts where the public's attention is low and/or there is an opportunity to mobilize single women during a presidential election. I also expect that they will make fewer references to single women when they comment on rules that target wives and/or mothers or rules that address moral issues.

Although rule making is a somewhat unknown and unconventional site for examining women's organizations’ lobbying strategies and women's representation, I focus on the comments that women's organizations submit during the rule-making process because rule making provides women's organizations with a unique opportunity to address the nuanced ways that policies can have unique effects on single women. Rule making is dominated by policy insiders with technical expertise (Golden Reference Golden1998; West Reference West2004; Yackee and Yackee Reference Yackee and Yackee2006). Therefore, when women's organizations submit comments during the process, they have a rare chance to use their expertise about women's issues to cite empirical data and/or provide a nuanced analysis of how policies influence women differently based on their marital statuses, parental statuses, and/or other identities. Rule making also typically occurs covertly, which means that it could also allow women's organizations to focus on single women, who the public has long stigmatized as lonely, miserable, selfish, immoral, and/or threatening, without the risk of creating a large public backlash (Abramovitz Reference Abramovitz1996, Reference Abramovitz2000; Bell and Kaufmann Reference Bell and Kaufmann2015; DePaulo Reference DePaulo2006; Hancock Reference Hancock2004; Klinenberg Reference Klinenberg2012; Mink Reference Mink2001; Stalsburg Reference Stalsburg2010).

Using the comments that women's organizations submit to rule makers to answer the questions described in the preceding section, I provide critical new information about the degree to which the diversity of single women's experiences are represented during regulatory policy debates. Although the number of single women is increasing, their concerns are largely absent from the comments that women's organizations submit to rule makers. Instead, women's organizations tend to focus on mothers (whom they often assume are married) 71.6% of the time, obscuring single women's unique policy interests and concerns, and denying them the opportunity to debate and discuss the ways that different policies affect different types of single women in unique ways. My results also unexpectedly show that the policy-making context has little relationship to whether or not women's organizations mention single women during rule-making debates.

WHY SHOULD WOMEN'S ORGANIZATIONS DISCUSS SINGLE WOMEN'S INTERESTS AND EXPERIENCES?

Although the single women's constituency did not turnout as many had hoped they would in 2016, women's organizations should still attempt to address their concerns because they are a large, growing, and important portion of the American population with unique policy interests. As of 2016, 49.2% of women were single, up from only 38.1% in 1970 (CPS 2017b). Many of these women are also now marrying and becoming mothers (single or married) later in life. The median age of first marriage increased from 20.8 years old in 1970 to 27.4 in 2016, and the number of childless women between the ages of 15 and 44 increased from 35.1% in 1976 to 48.6% in 2016 (CPS 2017c; 2017d). Thus, women are increasingly spending large periods of their lives living alone (Klinenberg Reference Klinenberg2012), and they are developing new policy interests and concerns based on their experiences in those years. For example, many single women share some broad interests in economic security, particularly because women, on average earn only 80.5 cents for every dollar their male counterparts make (IWPR 2019); and 25.7% of households headed by single mothers and 23.2% of women living alone outside of families are in poverty, compared with 12.2 of male-headed households, and 4.9% of married couple families (US Census 2016–2017a). Single living is also often more expensive because singles do not benefit from many of the economies of scale that help keep costs of living down for couples and families unless they are willing and able to live with others (DePaulo Reference DePaulo2006; Klinenberg Reference Klinenberg2012). Plus, many single women do not benefit from thousands of federal policies that direct material benefits toward married couples (DePaulo Reference DePaulo2006). Thus, single women, who are forced to rely on their own, often smaller incomes, do have some shared interests in issues such as pay equity, affordable housing, health care, and education (DePaulo Reference DePaulo2006). However, not all single women experience this economic insecurity in the same ways. Some, such as women of color and/or single mothers, experience greater wage gaps and higher levels of poverty than their white and/or married counterparts (IWPR 2019; US Census 2016–2017a, 2016–2017b). Similarly, young, never-married women may be more willing to live with roommates, and older widows may be able to live with adult children, making it clear that different types of single women have different types of options available to them as they navigate these economic pressures.

Moving beyond economic issues, some single women benefit from the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) or other policies that allow women to better balance their working lives with their personal lives or their care responsibilities. In theory, these policies could benefit single and married women alike, by providing them the time and the space they need to develop their own relationships, care for their children (if they are mothers), or care for themselves. However, some single women, particularly those who are childfree, often face unique challenges when they confront the issues these policies are meant to address. For example, the FMLA does not provide job-protected leave for many of the people, such as “chosen families” of other adult friends or siblings, that a childfree adult single woman would need to rely on for care if she had a major health issue because it only provides leave to care for a spouse, a child under 18, or a parent who has a serious health condition (DePaulo Reference DePaulo2006; US Department of Labor 2018). Moreover, some single, childfree women have reported that though they value policies that provide them with greater work–life balance, those policies can have negative consequences for them when some of their married or parenting coworkers assume they do not have personal lives outside of work, so single women can work longer or more inconvenient hours (Klinenberg Reference Klinenberg2012). As a result, some single women may actually resent their married or parenting counterparts when they feel like work–life policies are designed for their married or parenting counterparts, not for them (Klinenberg Reference Klinenberg2012).

Some women's organizations and activists also assume that single women are uniquely interested in reproductive rights issues, likely because younger, unmarried women experience higher rates of unintended pregnancy than their married counterparts (Guttmacher Institute 2019). Although it is likely that many women, both single and married, would benefit from policies that expand access to contraception and/or abortion, discussions about these issues also often obscure many of the differences that exist between young unmarried women and other women on these issues. For example, during the 2004 election, the media and many campaigns equated all single women with a group of young, attractive, sexually available, upscale, white single women that they deemed “Sex and the City Voters (SATC),” and they tried to appeal to them by selling them underwear with political slogans or equating voting with a “hair appointment they could not miss” (Anderson and Stewart Reference Anderson and Stewart2005; DePaulo Reference DePaulo2006). More recently, young, single women have been denigrated as “Beyoncé Voters” who “depend on the government because they're not depending on their husbands” and who “need things like contraception” (Watters Reference Watters2014, quoted in Valenti Reference Valenti2014). As a result, many discussions about “single women's” interests in reproductive rights have failed to recognize that many women experience this issue in different ways. For instance, they do not address how reproductive rights issues likely take on a unique significance for single mothers, and women of color in particular, who have long been demonized for being lazy, dependent, and promiscuous “Welfare Queens” (Abramovitz Reference Abramovitz1996, Reference Abramovitz2000; Hancock Reference Hancock2004; Mink Reference Mink2001). Narrowly focusing on young, single women also obscures the fact that older, unmarried women who have not yet found partners may actually want to become pregnant, rather than preventing pregnancy, but they have been unable to do so because of the high costs associated with egg freezing and/or in vitro fertilization (Carbone and Cahn Reference Carbone and Cahn2013). It also hides the fact that many postmenopausal single women or single women in same-sex relationships may not be highly concerned about preventing pregnancy.

Even though all of the examples in the preceding section suggest that single women and married women, all have the potential to benefit from policies designed to improve women's economic security, work–life balance, and/or access to reproductive rights, they also reveal that single women, and different types of single women, may experience these issues differently. However, when activists discuss these issues, they often paper over the differences that exist between women based on their marital statuses, whether or not they have children, their ages, their races or ethnicities, and/or their sexual orientations. Thus, I argue that although single women have some shared policy concerns, they will fail to emerge as a powerful political constituency until women's organizations help them debate and discuss their unique policy interests by explicitly mentioning their concerns during policy debates.

In this study, I posit that women's organizations have a critical role to play in articulating single women's interests because they are the political actors who are best positioned to represent single women during the rule-making process. Though bureaucratic officials and individual women also participate in rule making, women's organizations exist specifically to represent women and to articulate their interests during policy debates (Goss Reference Goss2013; Katzenstein Reference Katzenstein1998; Kenney Reference Kenney2003; Strolovitch Reference Strolovitch2007; Weldon Reference Weldon2011). Moreover, in recent years, the community of women's organizations has also become increasingly professionalized and diversified as many new organizations have formed to participate in insider forms of lobbying (e.g., rule making), and to represent women (e.g., women of color and LGBTQ women), who have long been excluded from the mainstream women's movements’ lobbying campaigns (Banaszak Reference Banaszak2010; Goss Reference Goss2013; Strolovitch Reference Strolovitch2007). Thus, contemporary women's organizations should have the experience needed to provide information about how proposed rules affect women differently based on their marital and parental statuses (as well as on differences based on race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, gender identity, and/or socioeconomic status) and to submit high-quality comments that rulemakers find convincing (English Reference English2018; Furlong and Kerwin Reference Furlong and Kerwin2005; Golden Reference Golden1998; Yackee and Yackee Reference Yackee and Yackee2006).

Women's organizations’ comments also play a crucially important role in representing women during rule making by contributing to ongoing debates about what women's policy interests are or should be (Celis et al. Reference Celis, Childs, Kantola and Krook2014; Escobar-Lemmon and Taylor Robinson Reference Escobar-Lemmon, Taylor-Robinson, Escobar-Lemmon and Taylor-Robinson2014). For example, if 10 different women's organizations submit comments during the rule-making process and those comments provide 10 different perspectives about how a proposed rule will affect different groups of women, those organizations contribute to women's representation by debating and discussing the different ways that policies will influence different women. Thus, just by providing different perspectives on women's policy interests, women's organizations’ comments play an important role in the process of women's representation and the construction of women's interests from the ground up (Celis et al. Reference Celis, Childs, Kantola and Krook2014; Escobar-Lemmon and Taylor-Robinson Reference Escobar-Lemmon, Taylor-Robinson, Escobar-Lemmon and Taylor-Robinson2014).

WHY WON'T WOMEN'S ORGANIZATIONS DISCUSS SINGLE WOMEN?

Despite increases in the number of single women and the important role that women's organizations play in representing the diversity of women's experiences during rule making, my first hypothesis states:

H1(Limited Attention Hypothesis):

Women's organizations’ comments will rarely explicitly mention single women (defined as “single women,” “divorced women,” “never-married women, “separated women,” “single mothers,” “unmarried women,” and widows”).

This hypothesis draws on previous research on women's organizations’ legacies of maternal activism, policy feedback, gendered assumptions of the American welfare state, and persistent stigmas against single women to argue that women's organizations face many barriers in their attempts to advocate for women during rule-making debates.

Women's Organizations’ Legacy of Maternal Activism

First, women's organizations may downplay the concerns of single women because they have long used women's traditional roles as wives and mothers to justify their advocacy efforts. For example, nineteenth-century women's activists reconciled their advocacy work with the doctrine of separate spheres and beliefs that women should primarily be responsible for caretaking and nurturing both inside and outside of the home with a logic of maternalism that highlighted women's unique moral authority based on their caretaking roles (Mettler Reference Mettler1998; Skocpol Reference Skocpol1992). Often, these maternal appeals were successful because they did not threaten assumptions that families consisted of a male breadwinner married to a female homemaker and they did not challenge established male political, business, or labor interests (Skocpol Reference Skocpol1992).

Even as late as the 1960s and 1970s, the agendas of many large, national women's organizations, such as the National Organization for Women (NOW), remained focused on the concerns of a relatively narrow group of upper- and middle-class, heterosexual, white, married women (Moran Reference Moran2004). For instance, NOW's founding charter emphasized the idea that married women should no longer have to choose between their careers and their home lives (NOW 1966), but it did not acknowledge that some women, most notably women of color, had long been forced to combine work in unglamorous, domestic service jobs (often for white families) with their family lives (Rosen Reference Rosen2006). Thus, unlike their upper-middle class, white counterparts many black women, “often dreamed of spending more time, not less with their families” (Rosen Reference Rosen2006, 276). Similarly, lesbian women were explicitly excluded from NOW after Betty Friedan characterized them as a “lavender menance” that would allow feminists’ critics to portray them as “man-hating dykes” (Rosen Reference Rosen2006, 166). Although NOW and other Second Wave organizations have long been critiqued for these exclusions, less attention has been given to how they also excluded unmarried women. Not only did Betty Friedan see lesbians as a lavender menace, she also saw never-married women as lonely and devastated by their failure to marry and have children, preventing her from addressing many of their unique experiences with work and family issues (Moran Reference Moran2004). Putting all of these exclusions together reveals that while leading Second Wave organizations like NOW promoted policies, such as equal rights at work and reproductive rights that theoretically benefitted all women, their early intensive focus on work–life balance for upper-middle-class, married, heterosexual women and the lack of attention they gave to women's differences based on race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, gender identity, and class made it difficult for Second Wavers to discuss single women's experiences or the differences that existed between different groups of women (Moran Reference Moran2004: Rosen Reference Rosen2006).

Maternalism and an emphasis on heterosexual two-parent families still persists in women's advocacy efforts today. In the 1980s, candidates from both political parties attempted to appeal to all women by advocating for women who played traditional caregiving roles in two-parent middle-class families, giving rise to a new form of politicized motherhood (Deason, Greenlee, and Langer Reference Deason, Greenlee and Langner2015). This politicized motherhood created new pressures for women to “place family roles front and center in order to appear competent, well-balanced, or sufficiently feminine” (Deason, Greenlee, and Langer Reference Deason, Greenlee and Langner2015, 143). As a result, it elevated (married) mothers’ concerns while sending the subtle message that single, childfree women are deviant (Deason, Greenlee, and Langer Reference Deason, Greenlee and Langner2015). Similarly, though the “soccer moms” that were prominent during the 1996 presidential election accounted for less than 10% of the population, newspaper articles that mentioned them never mentioned any other subgroup of women, suggesting that focusing on soccer moms allowed campaigns to “appear to be responsive to the concerns of women voters while actually ignoring the vast majority of women” (Carroll Reference Carroll1999, 7). Altogether, this history of maternal activism suggests that even as women's roles have changed a great deal, it may be difficult for today's women's organizations to broaden their agendas to focus on the increasingly large number of single women, particularly if they are not mothers.

Policy Feedback and Gendered Assumptions in American Welfare State Programs

Many American social welfare programs also have a long history of distributing benefits based on the assumption that a “family” consists of a female caregiver who works in the home that is married to a male breadwinner who works in the labor market (Abramovitz Reference Abramovitz1996; Esping-Anderson Reference Esping-Anderson2009; Gordon Reference Gordon and Gordon1990; O'Connor, Orloff, and Shaver Reference O'Connor, Orloff and Shaver1999; Orloff Reference Orloff1996; Pateman Reference Pateman1988; Sainsbury Reference Sainsbury and Sainsbury1994; Sapiro Reference Sapiro and Gordon1990). Thus, marriage remains a crucial factor in terms of how many policies distribute benefits, rights, and privileges, and as of 2004, there were 1,138 federal policy provisions that used marriage to determine benefits or eligibility (DePaulo Reference DePaulo2006). For example, if a married woman applies for Social Security benefits, she has two options: she can receive benefits based on her own work record or she can apply for retirement benefits based on her spouse's record instead and married women often claim their (male) spouses’ benefits because they tend to be higher (Hartmann and English Reference Hartmann and English2009; Social Security Administration 2018). In contrast, women who never married or who were married for less than 10 years, have no such option to increase their retirement benefits, suggesting that their work histories and/or relationships are not as valuable.

Policy feedback related to these gendered assumptions about the family may further discourage women's organizations from advocating for single women. Policy feedback occurs when the ways that government policies distribute benefits shape what members of the public believe they want and how they participate in politics (Mettler and Soss Reference Mettler and Soss2004; Pierson Reference Pierson1993). Thus, when single women encounter a large number of social policies that provide married couples with benefits, but that do not help them, they may choose not to participate in politics, and women's organizations may focus on their more politically active married counterparts instead. Single women may also participate less than married women because policies provide them with fewer resources they can use to facilitate political action (Campbell Reference Campbell2003).

Persistent Stigmas and Myths about Single Women

Single women are also still a stigmatized, politically unpopular, and misunderstood constituency. For example, people still believe that single women are miserable, they do not have social lives outside of work, they are single-mindedly focused on finding a partner, and they are worried about dying alone (DePaulo Reference DePaulo2006). Single women have also reported that their friends and families consistently ask them about their dating status, they frequently encounter advice about how to make themselves more sexually attractive, and they even receive advice from doctors about how they should not have children at an advanced maternal age (Klinenberg Reference Klinenberg2012). Some have also been warned that they should not focus too much on jobs that will not “love them back” (DePaulo Reference DePaulo2006; Klinenberg Reference Klinenberg2012). Consequently, some single women may be hesitant to claim their singleness as part of their political identities. For instance, a single 40-year-old woman who runs a website for singles explained that she does not like to identify as single because “It makes me think of desperate unhappy people who can't get a date and that's never been who I am” (Klinenberg Reference Klinenberg2012, 135–136).

Members of the broader public also hold negative attitudes toward single women. For instance, voters rate childfree female candidates lower than childless male candidates, candidates who were mothers, and candidates who were fathers (Stalsburg Reference Stalsburg2010). Therefore, childfree women often experience “more whispers and sideways glances” than do childless men (Stalsburg Reference Stalsburg2010, 395). Similarly, single female candidates receive dramatically lower evaluations than candidates who are married mothers particularly among conservatives, implying that single female candidates are seen as threatening to the “identity and values of some men and women” (Bell and Kaufmann Reference Bell and Kaufmann2015, 6). Together, these studies imply that voters see single women as a political constituency that is socially deviant and weak. As a result, it is likely that voters and members of the broader public will prefer policies that punish them (Schneider and Ingram Reference Schneider and Ingram1993). Thus, women's organizations may also avoid mentioning single women to avoid triggering a public backlash against single women.

WHEN WILL WOMEN'S ORGANIZATIONS DISCUSS SINGLE WOMEN?

I expect that women's organizations will rarely explicitly advocate for single women; however, I also expect that they will strategically lobby for this growing constituency in contexts where they believe that they will be able to avoid triggering a public backlash against single women or in contexts where they believe that mobilizing large numbers of single women will help them achieve their goals. Thus, my second hypothesis states that:

H2 (Opportunity Hypothesis):

Women's organizations’ comments will include more references to single women when they comment on rules that did not receive media attention and/or when they comment on rules that were proposed during presidential elections.

When the media covers the rule-making process, more members of the public should follow the process and scrutinize the comments that women's organizations submit. Therefore, in those contexts, women's organizations should make fewer references to the stigmatized group of single women that the public may want to punish (Schneider and Ingram Reference Schneider and Ingram1993). In contrast, when the media does not cover the process and public scrutiny is low, they may feel like they can include more references to single women.

Because the literature suggests that presidential campaigns and the media have focused more attention on some single women, such as SATC voters, during presidential elections (Anderson and Stewart Reference Anderson and Stewart2005; DePaulo Reference DePaulo2006), I expect that women's organizations’ comments will contain more references to single women when they respond to rules that were proposed in presidential election years. In those cases, women's advocacy organizations could use their comments to attempt to mobilize single women to turnout for the upcoming election.

I also expect that some contexts will encourage women's organizations to downplay single women's concerns. Thus, my third hypothesis states that:

H3 (Exclusion Hypothesis):

Women's organizations’ comments will include fewer references to single women when they comment on rules that target wives or mothers and/or address moral issues.

When women's organizations submit comments to federal rule makers, they must respond to the proposed rules that bureaucrats developed first, and bureaucrats are more likely to respond to comments that provide support for their proposals (English Reference English2016; Golden Reference Golden1998; Kerwin and Furlong Reference Kerwin and Furlong2011; West Reference West2004). Thus, women's organizations’ comments should echo the ways that the bureaucrats referred to women's marital and parental statuses when they described the target populations of their proposed rules, meaning that they should include relatively few references to single women when the proposed rules define the target population as wives and/or mothers. Similarly, I expect that the type of policy that the rule implements should have an influence on whether women's organizations discuss single women. When women's organizations comment on rules related to moral issues, such as reproductive rights, the definition of families, or protections for the religious community (Meier Reference Meier1999; Mooney Reference Mooney1999; Reference Mooney and Mooney2001), they should make relatively few references to single women who live outside of traditional families and traditional gender norms. Ignoring single women in those cases should help them avoid triggering the public's negative stereotypes about the immorality of single women and/or single mothers (Abramovitz Reference Abramovitz1996; Hancock Reference Hancock2004; Mettler Reference Mettler1998; Mink Reference Mink2001; Schneider and Ingram Reference Schneider and Ingram1993).

DATA AND METHODS

Why Rule Making?

To test my hypotheses, I collected all of the comments that women's organizations submitted to rule makers using the website www.regulations.gov between 2007 and 2013.Footnote 1 Rule-making comments are a somewhat unknown and unconventional choice for examining questions about which women are represented in policy debates, but I used them for this analysis because rule making provides women's organizations with a unique opportunity to lobby for single women who have historically been stigmatized by the broader public. Rule making occurs after Congress passes a law and it allows bureaucrats who work in federal agencies to “fill-in” the technical details that policies need to operate that legislators left out (Kerwin and Furlong Reference Kerwin and Furlong2011). The process has three legally required steps. First, federal agencies are required to publish a draft of their proposed rule in the Federal Register and to collect comments from interested citizens or organizations during a public comment period that typically lasts 1–2 months (Office of the Federal Register 2011). Second, the agency must review all of the comments it received and determine whether to make changes to its proposed rule. Third, the agency publishes its proposed rule and its responses to the comments in the Federal Register and the rule goes into effect.

During the rule-making process, agencies have considerable discretion to respond to the comments as they see fit. They are the most likely to respond to comments and incorporate suggestions from organized interest groups when they submit large numbers of comments, when they submit high-quality comments that rely on sophisticated empirical data analyses or legal arguments, when they submit comments that generally support the agency's proposed rule, and when a group of commenters (e.g., women's organizations) indicates that they have reached a consensus on the issue (English Reference English2016; Furlong and Kerwin Reference Furlong and Kerwin2005; Golden Reference Golden1998; West Reference West2004; Yackee and Yackee Reference Yackee and Yackee2006). Thus, bureaucrats may ignore the comments that women's organizations submit during the process, but even when they do that, participating in rule making still allows women's organizations to contribute to women's representation and to highlight the concerns of single women. Typically, rule making is a technical and detail-oriented process that is rarely covered in the media and often dominated by policy experts (Golden Reference Golden1998; West Reference West2004; Yackee and Yackee Reference Yackee and Yackee2006). Consequently, it often occurs under the public's radar, so it provides women's organizations an opportunity to lobby for constituencies, such as single women, that the public sees as deviant, weak, or undeserving (Schneider and Ingram Reference Schneider and Ingram1993). Second, women's organizations’ comments help women, and women's organizations debate which policies best serve women's interests by posting their comments on www.regulations.gov. After they post those comments, other women's organizations and interested individual women can read the comments and submit their own comments indicating that they either agree or disagree with the comments from the initial women's organizations. As this process occurs over and over, it contributes to the construction of women's policy interests from the ground up (Celis et al. Reference Celis, Childs, Kantola and Krook2014; Escobar-Lemmon and Taylor-Robinson Reference Escobar-Lemmon, Taylor-Robinson, Escobar-Lemmon and Taylor-Robinson2014).

Unit of Analysis and Dependent Variable

Because rule-making comments contribute to the construction of women's interests, my unit of analysis was an individual comment. Collecting and analyzing those comments was a multistage process. First, following the literature on interest groups and rule making (Furlong and Kerwin Reference Furlong and Kerwin2005; Strolovitch Reference Strolovitch2007), I compiled a comprehensive list of 471 women's organizations using three published directories of women's advocacy organizations (the National Council of Women's Organizations Directory, Congressional Quarterly's Washington Directory, and the Women of Color Organizations and National Projects Directory) and the literature on conservative women's organizations (Schreiber Reference Schreiber2008). I then searched www.regulations.gov for all of the comments that those organizations submitted between January 1, 2007 and December 31, 2013, and I identified 1,021 comments that women's organizations submitted in response to 264 different rules, or 1.35% of the 19,562 rules that agencies implemented between 2007 and 2013 (US GAO 2017).Footnote 2 Although those 264 rules only account for a small number of rules that the agencies implemented in this period, they provide insight into which women women's organizations discussed during rule making on a relevant set of rules that women's organizations considered to be of interest to women. Third, after I identified all of those comments, I used NVivo's automated text search feature to determine how many times they referred to single women (e.g., “divorced women,” “never-married women,” “separated women,” “single women,” “single mothers/moms,” “unmarried women,” and “widows”), married women (e.g. “wives” and “married women”), and mothers (e.g. “mothers” and “moms”). Then, I performed a qualitative analysis of how women's organizations discussed each of those different types of single women. I also created one aggregated measure for references to single women by adding up the number of times each comment mentioned “divorced women,” “never-married women,” “separated women,” “single women,” “single mothers/moms,” “unmarried women,” and “widows.” This raw aggregate count of references to single women serves as the dependent variable for my statistical analyses.

Independent Variables and Controls

My dataset also includes five independent variables related to my hypotheses and three controls. Media coverage indicates whether each comment responded to a rule that was covered in American newspapers during its public comment period. To code this variable, I conducted a LexisNexis search for newspaper articles using key words from the summaries of each rule. When the LexisNexis identified articles that explicitly mentioned the proposed rule or the rule-making process, the comment was coded “1,” indicating it responded to a rule that received coverage. All other comments were coded “0” for no coverage. Presidential election year was coded “1” for comments that were submitted in response to a rule that was proposed during a presidential election year, prior to Election Day. Targets wives and targets mothers account for whether or not the proposed rule targeted women based on their roles as wives or mothers. To code these variables, I used www.regulations.gov to download all of the proposed rules that the comments responded to, and then I used NVivo's automatic text search feature to search each of those documents for references to married women and mothers. Using those data, I coded the targets wives dummy variable “1” when the proposed rule the comment responded to included at least one reference to married women or wives. All other comments were coded “0.” I also coded the targets mothers variable “1” when the proposed rule the comment addressed included at least one reference to mothers or moms, and I coded all other comments “0.” I coded the proposed rules for references to wives and mothers, rather than for references to single women because none of the proposed rules explicitly mentioned single women. The final variable was used to account for whether or not the comment responded to a rule on a moral issue. I used the summaries of each rule to determine whether the proposed rule was a moral issue. Following the literature on morality politics, comments were coded “1” when they responded to rules that discussed “morality or sin” issues such as religious freedom, the definition of the religious community, sex, and/or sexuality (Meier Reference Meier1999; Mooney Reference Mooney1999, Reference Mooney and Mooney2001). Examples of rules in this category included rules on abortion and contraception, religious and moral conscience protections for healthcare workers, hospital visitation rights for LGBTQ families and friends, prostitution, HIV/AIDS funding, and housing programs for LGBTQ families.

Lastly, I included three control variables in my analyses. Conservative organization was used to identify comments that were submitted by women's organizations focused on promoting conservative values and/or challenging feminist groups. I controlled for conservative ideology because I expected that conservative organizations, which generally focus on promoting traditional families and gender roles (Deckman Reference Deckman2016; Schreiber Reference Schreiber2008), would be particularly unlikely to focus on single women's concerns. This variable was coded “1” when the organization's mission or vision statement indicated that it was focused on promoting traditional, conservative values and/or challenging liberal feminist groups. For example, comments from the Concerned Women for America (CWA) were coded “1” because CWA's website states that their mission is to “protect and promote Biblical values and Constitutional principles through prayer, education, and advocacy” (CWA 2018).

The variable Obama identifies which presidential administration proposed the rule that each comment addressed. It is coded “1” for comments that responded to rules that the Democratic Barack Obama administration proposed and it is coded “0” for comments on rules that the Republican George W. Bush administration proposed. I include this control variable because Democratic administrations have been more sympathetic to women since the early 1980s (Kaufmann and Petrocik Reference Kaufmann and Petrocik1999; Sanbonmatsu Reference Sanbonmatsu2004); thus, I expect that Democratic administrations are more receptive to comments that address single women's concerns. Lastly, I control for the number of words in each comment because longer comments provide women's organizations with more opportunities to refer to single women.

After I compiled the dataset, I ran a series of χ2 tests to examine whether each of the five contextual variables was associated with whether women's organizations’ comments included references to single women. Next, I used a negative binomial regression model to determine whether there was a relationship between the number of references the comments made to single women and the five contextual variables, controlling for all other factors. Following Long and Freese (Reference Long and Freese2006) and Wilson (Reference Wilson2015), I chose a negative binomial model because the likelihood ratio test indicated that the data were overdispersed, and the Akaike information criterion (AIC) and Bayesian information criterion (BIC) tests preferred the negative binomial model.

REFERENCES TO SINGLE WOMEN

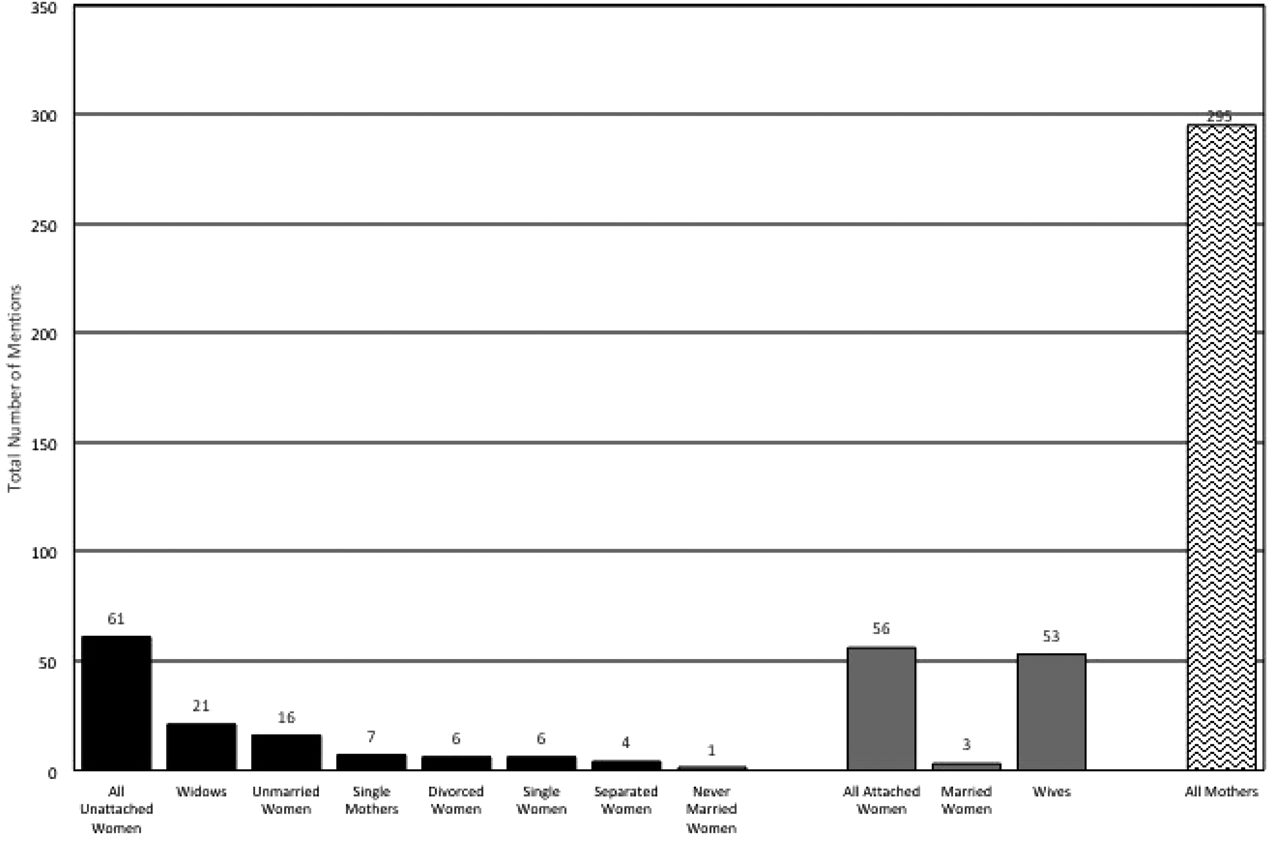

My limited attention hypothesis (H1) stated that women's organizations’ comments should only rarely refer to single women, and Figure 1 indicates that this expectation was met. Single women were only mentioned 61 times in 1,021 comments, or approximately 0.06 times per comment on average. The comments mentioned “widows” the most, followed by “unmarried women,” “single mothers,” “single women” and “divorced women,” “separated women,” and “never-married women.” Together, widows, divorced women, and separated women accounted for 50.8% of the comments’ references to women based on their marital statuses, showing that women's organizations devoted more attention to single women who were once married. “Married women” and “wives” were also only mentioned 56 times, indicating that women's organizations devote little attention to how policies affect women based on their marital status, regardless of whether they are married or single. However, women's organizations do focus on women's parental statuses in their comments; they mentioned “mothers” 295 times, or approximately 4.8 times as often as they referred to single women. Moreover, only 7 (2.4%) of those references to mothers were references to “single mothers,” indicating that many women's organizations assume married mothers are the norm.

Figure 1. Number of reverences to women by marital status and parental status in women's organizations’ comments, 2007–2013.

To get a better sense of what women's organizations felt constituted single women's policy interests, I also examined what they said about single women (and different types of single women) in their comments. They discussed widows’ concerns most often, and they raised their concerns during rule making on Tri-Care Health Plans (i.e., health plans for military service members and their families), family visitation rights in hospitals, survivor's annuities in retirement plans covered by the Employment Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA), and income verification procedures for widows who apply for the Department of Housing and Urban Development's (HUD) housing programs.

Women's organizations discussed “unmarried women” the next most often, and all of their references to them responded to rules about reproductive rights. The Guttmacher Institute encouraged the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) to rescind a rule that allowed healthcare workers to refuse to participate in medical procedures that they felt violated their religious beliefs or moral convictions because they that rule might allow healthcare workers to refuse to provide information or counseling about Pap tests or sexually transmitted infections (STIs) to “unmarried women they believed should be sexually abstinent.” The Center for Reproductive Rights and the Guttmacher Institute also submitted comments that indicated unmarried women would benefit from the Obama administration's contraception mandate (a rule that required all employer-sponsored group health insurance plans to provide women with access to all Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved conception methods without a copayment) because they tend to experience higher rates of unplanned pregnancy than other women, and improved access to contraception lowers their unintended pregnancy and abortion rates.

Women's organizations discussed single mothers’ concerns the next most often; they specifically discussed the importance of five policies for single mothers. First, a coalition of organizations explained that the Affordable Care Act's (ACA's) high-risk insurance pools are critically important for single mothers with pre-existing conditions. Another coalition highlighted the importance of the FMLA for single mothers who need to leave work to take care of their sick children. Legal Momentum explained that Immigration and Custom Enforcement's (ICE) policy for handling “no-match” letters for employment verification could increase the dangers that battered single mothers face when they try to leave their abusive marriages. Equal Rights Advocates noted that gender wage discrimination harms single mothers who are the sole breadwinners for their families to lobby for a rule that would require federal contractors to collect data on wage discrimination. Finally, the National Women's Law Center explained that the ACA's healthcare exchanges needed to provide a variety of payment options for single mothers because they are less likely to have bank accounts than others.

Next, women's organizations primarily discussed divorced women's interests in response to rules related to retirement. For example, a comment from a coalition of women's organizations explained that divorced women are economically vulnerable in retirement in response to a proposal to change the regulations for ERISA retirement plans.

Women's organizations also referred to “single women” six times, but many of those references drew attention to other groups of women. For example, Catholics for Choice explained that if the courts determined that it was unconstitutional to prevent single women from accessing contraception, then it was also unconstitutional to prevent women who work at certain religiously affiliated organizations from acquiring birth control. The Maryland Women's Coalition for Healthcare Reform also explained that separated women face challenges that other single women do not encounter when they have to jointly file taxes to claim the ACA's health insurance credit.

Finally, women's organizations devoted the lowest level of attention to never-married women, mentioning them just once in 1,021 comments to explain that “never-married women, are especially vulnerable in retirement … and 18% of never-married elderly women lived in poverty.” Given that 96% of never-married women are between the ages of 18 and 64 (CPS 2017a), it is remarkable that the only time they were mentioned in seven years of women's organizations’ comments was in response to a rule about ERISA retirement policies!

OPPORTUNITIES AND EXCLUSIONS

I also expected that women's organizations would be more likely to focus on single women when they commented on rules that did not receive media attention and when they commented on rules that were proposed during presidential election years. Also, they should be less likely to mention single women when they commented on moral rules or rules that targeted wives and mothers. The five insignificant χ2 tests in Table 1 indicate that at the bivariate level, these five contextual factors were not related to whether or not women's organizations’ comments mentioned single women. Similarly, the hypothesis tests on the coefficients for all five contextual variables in the model displayed in Table 2 were insignificant, indicating that the policy-making context was not related to how often women's organizations mentioned single women. Together, the insignificant results displayed in Table 1 and Table 2 disprove my opportunity (H2) and exclusion (H3) hypotheses.

Table 1. Context and references to all single women

DF, degrees of freedom

***P ≤ 0.01; **P ≤ 0.05; *P ≤ 0.10.

Table 2. Contextual effects on references to single women

***P ≤ 0.01; **P ≤ 0.05; *P ≤ 0.10.

DISCUSSION

Despite recent enthusiasm about the constituency of single women, I have shown they are often excluded from women's organizations’ rule-making comments, while also providing some new information about why women's organizations exclude them. First, women's organizations discussed married mothers five times as often as single women, underscoring the consequences of recent forms of politicized motherhood for single women. Thus, like Deason, Greenlee, and Langner (Reference Deason, Greenlee and Langner2015), I have shown that politicized motherhood has the potential to make single, childless women invisible, and my findings suggest that women's organizations, like political candidates, feel pressure to advocate for women by focusing on two-parent families.

Further research, including interviews with women's organizations’ staffers, is needed to understand the strategic decisions underlying women's organizations’ focus on mothers. However, previous research suggests that contemporary feminist organizations focus on mothers rather than single women to proactively defend their organizations against criticisms that they are antifamily (Deason, Greenlee, and Langner Reference Deason, Greenlee and Langner2015; DePaulo Reference DePaulo2006; Moran Reference Moran2004; Rosen Reference Rosen2006). It is also possible that they believe that most women will benefit from their advocacy efforts focused on mothers because many single women have benefitted from policy changes, like efforts to end wage discrimination or efforts to provide better work–life balance that also help married women (Moran Reference Moran2004). Perhaps they also believe that efforts to advocate for mothers will resonate with the many single women who plan to marry and have children one day (Klinenberg Reference Klinenberg2012).

My findings also provide some additional hypotheses and clues about why women's organizations rarely focus on single women. First, my qualitative results demonstrate that women's organizations have a relatively narrow understanding of single women's policy interests. Although they recognize that many different types of single women are economically vulnerable, they often only discuss how economic vulnerability affects women when they retire, seek health care, or try to secure public housing. Given that the ACA was high on the national agenda when this study was conducted, their focus on single women's health care makes sense. However, it is somewhat surprising that they did not consider how single women's economic insecurity was also connected to other issues that were on the rule-making agenda, including policies related to student loans and financial reforms related to the Great Recession. Likewise, single women often lack access to other adults who can take care of them when they are sick or otherwise incapacitated, but only one comment explicitly addressed this issue, and it only focused on the importance of hospital visitation rights for childless widows. Thus, the commenters failed to acknowledge that broader definitions of the family that could help other single women too. For example, broadening the definition of family members under the FMLA could also allow younger, never-married women to identify people who could take job-projected leave to care for them. Interestingly, the comments did not address these issues, even as the United States v. Windsor (2013) case raised many questions about how the government would reconsider marital status in determining eligibility for benefits and programs.

Women's organizations’ comments also suggested that “unmarried women” were primarily, if not exclusively, interested in abortion and contraception. Once again, this focus is understandable given the ACA's prominent role on the national agenda and the highly salient debate about contraceptive coverage under the ACA. However, it is likely that unmarried women have policy interests beyond reproductive rights, and this narrow focus on unmarried women's sex lives risks reinscribing negative stereotypes that unmarried women are selfish and/or promiscuous, raising questions about why their interests were not described more broadly. Once again, interviews with staff members at women's organizations could help flesh out this issue.

Finally, I unexpectedly showed that key features of the policy-making context, including the rule's target population, its focus on morality, the level of media coverage it received, and whether or not it was a presidential election year, were not related to how often women's organizations referred to single women. This lack of contextual effects is remarkable given that previous research has found that the rule's target population, level of media coverage it received, and focus on morality were significantly related to how often women's organizations referred to women's sexual orientations, gender identities, and socioeconomic statuses in their comments (English Reference English2018). More research is needed on this point, but the lack of contextual effects could be due to the fact that women's organizations simply make too few references to single women for the context to matter.

Women's organizations’ lack of attention to single women could also be driven by another factor, the very small number of women's organizations that exist to lobby for single women based on their marital status. In a previous study, English (Reference English2018) also found that there was a significant relationship between the presence of women's organizations dedicated to sexual orientation, gender identity, and socioeconomic status, and the number of times that women's organizations mentioned women's sexual orientations, gender identities, and socioeconomic statuses in women's organizations' comments. In contrast, none of the organizations included in this study explicitly represented single women. Thus, women's organizations may not focus on single women because they have not yet formed niche organizations that would force their issues onto broader women's movement's agenda. Such organizations may not yet exist because many women still hesitate to identify as single (Klinenberg Reference Klinenberg2012).

CONCLUSIONS

Single women have long been stigmatized and marginalized by members of the public, the broader women's movement, and American social policy, and my findings indicate that they are still excluded from the women's movement's rule-making comments, despite their rising numbers and the unique opportunities rule making provides to focus on them. Because women's organizations devote a great deal of attention to married mothers, my findings suggest that these exclusions can be partially attributed to the recent trend toward politicized motherhood. They also indicate that the path ahead for single women is difficult given the narrow depictions of their interests, the lack of political contexts that encourage women's organizations to focus on their concerns, and a lack of niche organizations devoted to them. Until women's organizations overcome some of those challenges and take political risks to advocate for this group and single women start to claim this political identity, it is likely that single women will continue to participate in politics at lower rates, limiting their potential to transform American politics, however large their numbers.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X1900028X.