The sociodemographic representativeness of political institutions constitutes a topic that is high on the political agenda in a large number of countries across the globe. The underrepresentation of specific groups in political institutions is increasingly considered a democratic problem (Phillips Reference Phillips1995); therefore, many countries have undertaken action such as implementing quota systems (Dahlerup Reference Dahlerup2007). The underrepresentation of women in parliaments has also been a topic of academic scrutiny for several decades. Pippa Norris (Reference Norris, LeDuc, Niemi and Norris1996) made an important contribution to this literature by developing a common framework to examine the presence of women in parliaments. This framework focuses on three levels of analysis: the recruitment environment, the recruitment structures, and the recruitment process.

Previous research has shown that the electoral system, an essential element of the recruitment environment, has a large effect on the presence of women in parliaments (Norris Reference Norris, LeDuc, Niemi and Norris1996; Matland and Montgomery Reference Matland and Montgomery2003). There seems to be a consensus among scholars that a system of proportional representation (PR) is more favorable for the election of women than a majority system (Norris Reference Norris, LeDuc, Niemi and Norris1996; Caul Reference Caul1999; Matland and Montgomery Reference Matland and Montgomery2003). However, there is a large variety in the gender equality of the outcomes of PR systems and in the ways actors use the institutional provisions of these electoral systems (Tremblay Reference Tremblay2008). To gain a better understanding of the effect of the recruitment environment on the presence of women, we study preferential voting and how the use of preference votes influences the descriptive representation of women.

Studies on how many preference votes female candidates obtain and what kind of voters are more likely to vote for them (and under which conditions) have mainly focused on the context of majority systems, in particular on the U.S. context with a two-party system (e.g., Brians Reference Brians2005; Dolan Reference Dolan2008; McDermott Reference McDermott1997; Paolino Reference Paolino1995; Sanbonmatsu Reference Sanbonmatsu2002; Smith and Fox Reference Smith and Fox2001). Only recently have some studies on voting for women in more proportional systems appeared (Giger et al. Reference Giger, Holli, Lefkofridi and Wass2014; McElroy and Marsh Reference McElroy and Marsh2010, Reference McElroy and Marsh2011). The aim of this study is to contribute to this recent literature by investigating another type of PR system—Belgium's flexible list system. In this electoral system voters can cast a vote for one or more candidates within one list or they can cast no preference vote but support the list as a whole (i.e. a list vote). Hence, voters can use their preference votes to influence the presence of women in parliament in multiple ways: they can choose to vote for one or more female candidates, one or more male candidates or both female and male candidates.

In addition to the specific nature of the preferential system, the 2012 local elections in Belgium are particularly interesting for yet three other reasons. First of all, quota legislation stipulates that in every municipality the number of female candidates is equal to that of male candidates. Hence, an important contextual variable (the number of female candidates in an electoral district) is held constant (McElroy and Marsh Reference McElroy and Marsh2010). Moreover, in previous research a strong relation between the presence of female candidates and the ideology of a political party was found, making it difficult to assess whether voters deliberately choose to vote for women or whether the candidate of their preferred party just happened to be a woman (Dolan Reference Dolan2008). Given the equal (and large) supply of female candidates in Belgium, we are better able to disentangle the effect of sex and ideology on voting for female candidates. Second, Belgian voters are allowed to cast several preference votes; thereby the competitiveness between candidates tends to be lower. This is likely to increase the chances of women candidates, as voters will be less likely to cast a strategic vote for men to increase the chances of gaining a seat for their preferred party. Likewise, we expect the number of seats available in a district (i.e. district magnitude) to be less important than in previous studies investigating electoral systems where voters are allowed to cast only one preference vote (Giger et al. Reference Giger, Holli, Lefkofridi and Wass2014). Finally, contrary to most research on gender-based voting that focuses on low information contexts, this study investigates voting behavior in a high information context given that voters are often familiar with the candidates in the Belgian local elections (Deschouwer Reference Deschouwer2009). As a result, we expect information shortcuts that are important when information costs are high, such as the sex of the candidate, to be used less (McDermott Reference McDermott1997).

In this article, we present the results of a thorough investigation of how preferential voting influences the descriptive representation of women in representative assemblies. In particular, we map the frequency and analyze the determinants of voting for male, female, or both male and female candidates. We study the characteristics of the voters (such as sex and ideology) as well as the characteristics of the electoral context (such as district magnitude). The analysis is based on the results of the 2012 PARTIREP Exit Poll survey that was conducted in a random sample of 40 local municipalities in Belgium at the occasion of the 2012 local elections (Dassonneville et al. Reference Dassonneville, Marien and Hooghe2012). Voters were interviewed face-to-face right after they left the polling booth. After this interview, they were asked to cast their (preference) vote(s) again on a “mock ballot” (self-administered). This research design results in a unique dataset that contains extensive information on the preference votes of the respondents.

In subsequent sections, we give an overview of the literature on gender-based voting, which leads to five hypotheses. Next, we discuss in greater detail why Belgium is an interesting case to test these hypotheses. Subsequently, we describe the data and methodology and present the findings of this study. We close with a discussion of the main results.

POLITICAL REPRESENTATION OF WOMEN AND ELECTORAL SYSTEMS

An inclusive society, where the interests of all citizens receive equal consideration in the political process, serves as an important normative ideal for social scientists and policymakers. Inclusive legislatures are perceived as more legitimate (Thomas Reference Thomas, Thomas and Wilcox1998) and also the quality of public policy increases when all relevant perspectives and interests are taken up in the debate (Habermas Reference Habermas1989). The descriptive representativeness of political institutions decreases the possibility that some interests or issues are overlooked (Paolino Reference Paolino1995; Mansbridge Reference Mansbridge1999). In effect, empirical research has shown that different groups put different issues on the parliamentary agenda supporting the idea that descriptive representation fosters substantive representation (Erzeel Reference Erzeel2012; Mansbridge Reference Mansbridge1999; Schwindt-Bayer Reference Schwindt-Bayer2006). In addition, inclusive legislatures are also of symbolic importance, as they foster the belief that the political process is open to all groups in society. In effect, the presence of female role models fosters the belief of women in their ability to run and increases their political engagement (Alexander Reference Alexander2012; Wolbrecht and Campbell Reference Wolbrecht and Campbell2007; but see Studlar and McAllister Reference Studlar and McAllister2002).

However, contemporary societies rarely live up to this ideal. Gender inequality is even, as Kenworthy and Malami (Reference Kenworthy and Malami1999, 235) note, perhaps most pronounced within the political arena. Female presidents and prime ministers remain rare; Paxton, Kunovich and Hughes (Reference Paxton, Kunovich and Hughes2007) counted worldwide only 30 women who were elected to this top position in their country. The percentage of women in legislatures, too, is disproportionally low in regard to the share of women in the population. At the beginning of the 21st century, less than 30% of the legislature consisted of women in the overall majority of the countries leading to a worldwide average of 10% of women in legislatures (Kenworthy and Malami Reference Kenworthy and Malami1999, 235–36). In recent years, this pattern has not changed all that much (Paxton, Kunovich, and Hughes Reference Paxton, Kunovich and Hughes2007).

Several studies showed that the political representation of women is strongly influenced by the electoral system (Matland and Montgomery Reference Matland and Montgomery2003; Norris Reference Norris, LeDuc, Niemi and Norris1996). In general, a system of proportional representation is found to be more favorable for gender equality in legislatures than a majority system (e.g., Norris Reference Norris, LeDuc, Niemi and Norris1996; Matland and Montgomery Reference Matland and Montgomery2003; Leijenaar Reference Leijenaar, Meier and Celis2004). In addition to institutional arrangements, the ways in which actors, such as voters and parties, use the institutional provisions of the electoral system influence gender equality in legislatures (Tremblay Reference Tremblay2008). Studying voting behavior can further our understanding of the underrepresentation of women in representative assemblies. To date, the results of empirical studies on the effect of voting behavior on the election of women to representative assemblies are mixed. Some studies provide evidence that female candidates obtain fewer votes than their male counterparts, while other studies find women to obtain more votes (Leijenaar Reference Leijenaar, Meier and Celis2004; Sanbonmatsu Reference Sanbonmatsu2002; Smith and Fox Reference Smith and Fox2001). As a result, Ballmer-Cao and Tremblay (Reference Ballmer-Cao and Tremblay2008) even stated that a system of preferential voting renders the outcome of the elections in terms of representation of women only more unpredictable.

FACTORS INFLUENCING VOTING FOR WOMEN

The aim of this study is to investigate the determinants of voting for female and male candidates. We begin the investigation by describing the voter and context characteristics that were found to influence voting for female or male candidates in previous research. A first important determinant is the sex of the voter. Women are theorized to be more likely to vote for women candidates. There are several causal mechanisms that underlie this claim. First, Dolan (Reference Dolan2008) theorizes that women are more likely to vote for female than male candidates because of a “gender affinity effect.” Gender identity can indeed be considered an important voting motive (Banducci and Karp Reference Banducci and Karp2000). It is argued that a vote is cast based on solidarity to candidates of one's own group rather than partisan affiliation, ideological stances, or an evaluation of the capacities of the candidate. A condition for such a group identity vote is the clear delineation of the group in society (objective membership) and its correspondence to a subjective identification translated in a form of group solidarity and consciousness (Gurin, Miller, and Gurin Reference Gurin, Miller and Gurin1980).

A second reason why women vote for female candidates is that the sex of a candidate can be considered as an important voting cue. Politics and elections are complex to many citizens. In order to make a deliberate choice at the polls, citizens often have to rely on voting cues, especially in elections with limited information. The most used cue is party affiliation (Plutzer and Zipp Reference Plutzer and Zipp1996). By running for a particular party, the candidate communicates to the voter where he or she stands. A voter expects, for instance, that a candidate of a social-democratic party will advocate the maintenance and further development of social services. By making this kind of generalization, it becomes easier and less time-consuming for voters to make an electoral choice. Associative cues can also be used by voters—that is, based on the group candidates belong to, voters can make inferences about candidates (Cutler Reference Cutler2002; McDermott Reference McDermott1997, Reference McDermott2009). A possible inference could be that female candidates will defend women's interests. The presence of female representatives is indeed found to be crucial in order to ensure that gender-salient issues are not overlooked (Erzeel Reference Erzeel2012). Yet we should note that defining and measuring women's interests is challenging. There is an ongoing debate within the literature about what these interests include (Paxton, Kunovich, and Hughes Reference Paxton, Kunovich and Hughes2007).

Sanbonmatsu (Reference Sanbonmatsu2002) discusses a third reason why the sex of a candidate can have an impact on the decision of voters. She argues that voters have a “gender baseline preference” that is based upon the gender stereotypes they have. The reasoning is that stereotypes that consider women as less suited for political careers lead to fewer votes for female candidates and, as a result, to fewer elected female politicians. This implies that an associative cue can also be used in a negative sense: voters refrain from voting for female candidates because they think that women in general are not as capable of a political function as their male counterparts.

Empirical studies resulted in mixed evidence on the occurrence of women voting more for women candidates. In the United States several studies indeed document that women are more likely to vote for female candidates than male candidates (Brians Reference Brians2005; Dolan Reference Dolan1998, Reference Dolan2008; Paolino Reference Paolino1995; Plutzer and Zipp Reference Plutzer and Zipp1996). Women were even found to be willing to shift political party in order to vote for a female candidate (Cook Reference Cook, Cook, Thomas and Wilcox1994). In Belgium, previous research on the national elections found an effect of sex and education with higher-educated women being more likely to vote for women (Carton Reference Carton, Swyngedouw, Billiet, Carton and Beerten1998). However, in other studies women were not more likely to vote on female candidates (McDermott Reference McDermott2009; King and Matland Reference King and Matland2003). Especially, outside the U.S. context, evidence of a gender affinity effect is rather limited to date (Goodyear-Grant and Croskill Reference Goodyear-Grant and Croskill2011; Holli and Wass Reference Holli and Wass2010; McElroy and Marsh Reference McElroy and Marsh2010, Reference McElroy and Marsh2011).

H1:

Women are more likely to vote for female candidates than men.

The use of associative cues is particularly relevant for voters that are not very politically sophisticated and accordingly lack the cognitive skills or motivation to become politically informed. Based on the reasoning behind associative cues, it could be expected that less politically sophisticated voters are more likely to vote for candidates of the same sex. Therefore, choosing women candidates can be expected to be a function of political sophistication.

H2:

Women with a lower level of political sophistication are more likely to cast a vote for female candidates than women with a higher level of political sophistication (same-sex vote).

In addition, it is argued that voters supporting left-wing parties are more likely to vote for female candidates than voters supporting right-wing parties (Dolan Reference Dolan2008; Matland Reference Matland1994). On the one hand, we can argue that left ideologies emphasize egalitarian values and support for subordinated groups and thereby increase the odds of voters with a left-wing orientation to support female candidates. On the other hand, political parties that are situated at the left of the ideological spectrum—such as social-democratic and green parties—are generally more in support of egalitarian ideologies and put equality issues on the political agenda more often. This openness can be translated into recruiting more women, giving them better positions on the list, and giving them more support in the election campaign (Matland and Studlar Reference Matland and Studlar1996). In effect, in majority systems political parties at the left of the ideological spectrum are more likely to select a female candidate than right-wing parties. However, in PR systems, too, the supply of female candidates is often unequally distributed among political parties (Dolan Reference Dolan2008; McElroy and Marsh Reference McElroy and Marsh2010). Hence, it might be that voters with a left-wing orientation are not more likely to vote for female candidates but that their preferred left-wing party just happens to have more female candidates at elections (Dolan Reference Dolan2008). This “party/sex overlap” that exists in several countries makes it difficult to assess whether left-wing voters are more likely to vote for female candidates or whether their preferred party just has more female candidates. Given the Belgian quota regulation, all political parties have an equal supply of candidates from both sexes. Consequently, the “party/sex overlap” is less salient in Belgium. Therefore, we are better able to investigate whether the ideology of the respondent influences the likelihood of voting for female candidates.

H3:

Voters with a left-wing orientation are more likely to vote for female candidates than voters with a right-wing orientation.

Recently, it has been argued that voting for women is not (so much) driven by individual variables (voter bias), but by the context in which elections are held (Wauters, Weekers, and Maddens Reference Wauters, Weekers and Maddens2010; Giger et al. Reference Giger, Holli, Lefkofridi and Wass2014). Although important, individual-level variables can explain only a part of the story. Therefore, context-related factors should be included in the analysis. In the literature three different contexts are considered relevant for voting for women: the political system, the electoral district, and the political party. As the political system (including electoral system, quota regulations, attitudes toward women in society, etc.) remains constant in this single-country study, we will focus on the electoral district and the political party.

The characteristics of the district in which the elections are held are considered to be of crucial importance for voting for women (Giger et al. Reference Giger, Holli, Lefkofridi and Wass2014). Given that elections in small districts tend to be more competitive, political parties more often select candidates with a broad appeal, and voters tend to vote only for candidates who have a real chance to become elected. As a result, women are likely to encounter more difficulties in small districts (especially when voters are allowed only to cast a single vote). This phenomenon is apparent in majority systems but also in PR systems with small district magnitude. Related, women are less likely to be selected in highly competitive elections (i.e., the closeness of the contest) (Giger et al. Reference Giger, Holli, Lefkofridi and Wass2014).

Another important context variable is the ratio of male and female candidates running (McElroy and Marsh Reference McElroy and Marsh2010). The supply of female candidates is important: the more (valuable) female candidates, the higher the chance to cast a vote for a woman (McElroy and Marsh Reference McElroy and Marsh2010). In general, female candidates are underrepresented on the ballot. Moreover, not only the ratio of male and female candidates is important, but also the position of a candidate on the list affects the number of votes he/she attracts. In effect, the first candidate on the ballot list is the most visible candidate position, which, due to the ballot layout effect (Geys and Heyndels Reference Geys and Heyndels2003; Lutz Reference Lutz2010; Wauters, Weekers, and Maddens Reference Wauters, Weekers and Maddens2010), quite automatically obtains a higher number of preference votes (Marissal and Hansen Reference Marissal and Hansen2001). Political parties play a crucial role as they determine the rank order of the list. In practice, women are seldom given this top position of the list (Wauters, Weekers, and Maddens Reference Wauters, Weekers and Maddens2010).

Before formulating hypotheses on the influence of the context on voting for female candidates, we describe the characteristics of the Belgian local election context more in greater depth given that these characteristics have an impact on these hypotheses.

BELGIUM AS AN INTERESTING CASE

Participation in elections is compulsory at all levels of governance in Belgium, which resulted in the 2012 municipal elections in a turnout rate of 89.7%. At all levels of electoral competition a PR system with rather large districts and flexible lists is used in Belgium: voters can either vote for a party list or for one or more candidates (on a single-party list). Candidates receiving sufficient preference votes to pass the election threshold are automatically elected. The other candidates can make use of the list votes in order to reach the threshold. These list votes are distributed to candidates according to their order on the list offering a substantial advantage to candidates at the top of the list. Consequently, the system used to function as a de facto closed-list system. This changed recently as a result of an increasing number of preference votes at the expense of list votes as well as an electoral reform that decreased the impact of list votes on the allocation of seats to candidates (by dividing the number of list votes by three before distributing them) (André, Wauters, and Pilet Reference André, Wauters and Pilet2012). As a result, more low-ranked candidates have managed to get elected at the expense of higher-ranked candidates. Consequently, the present Belgian electoral system can be characterized as a de facto semi open-list PR system. In practice, the local electoral system has been more open compared to the other levels as more voters cast preference votes and more candidates are elected in defiance of the party's ranking at the local level. For instance, even before the electoral reform, more than two-thirds of the local councilors were elected without using any list votes (Wauters Reference Wauters2000).

Within the elections in Belgium voters do not necessarily have to make a choice between voting for male or female candidates: they can vote for both (mixed-gender vote) or for the party list as a whole (list vote). Moreover, a vote for a male candidate does not preclude a vote for a female candidate, or, in other words, voting for women is not at the expense of voting for men. We expect this particular element to break down the barriers to vote for female candidates. In the literature, it is argued that in small districts or in highly competitive electoral contests voters are more likely to cast a strategic vote for men in order to increase the chances of gaining a seat for their preferred party rather than for the person of their preferred sex (Giger et al. Reference Giger, Holli, Lefkofridi and Wass2014). Given that voting for male and female candidates can easily be combined in Belgium, we do not expect that district magnitude has an effect on voting for female candidates. In line with this expectation, a study of the Belgian local elections in 2000 described the correlation between district magnitude and preference votes for women to be weak (Marissal and Hansen Reference Marissal and Hansen2001).

H4:

District magnitude has no effect on the likelihood to vote for female candidates.

The long-existing and far-reaching quota system is another element that makes Belgium an interesting case to analyze. Legislation aimed at increasing the proportion of women on candidate lists was introduced rather early in Belgium (Celis and Meier Reference Celis and Meier2006; Meier Reference Meier2004). In 1994, a first quota law was introduced at the national level stating that a maximum of two-thirds of the candidates on a list could be of the same sex. In 2002 this was changed into the requirement that electoral lists should contain an equal number of male and female candidates (or differing by one in the case of an odd number of candidates). In addition, one of the two highest (often safe, eligible) positions on the list should be reserved for a female candidate. In 2005, a similar quota regulation was adopted at the municipal level and—after some transitional measures—the regulation is applied in full force in the 2012 local elections.

As a result, the presence of women on the list cannot influence the propensity to cast a vote for women. This does not mean, however, that the composition of the list does not matter. The number of women at the first position of the list is not guaranteed, and research has shown that this top position is mostly granted to a man (Wauters, Weekers, and Maddens Reference Wauters, Weekers and Maddens2010; de Moor, Marien, and Hooghe Reference de Moor, Marien and Hooghe2013). At all levels of electoral competition this candidate has the largest chance of being elected because he/she is the first in line to use the list votes to reach the threshold. The position itself increases the number of preference votes, too, because of the ballot layout, the amount of media exposure, and the amount of campaign funding received from the political party—as well as the party finance regulations that allow this candidate to spend more money on his/her campaign than other lower-ranked candidates (Wauters, Weekers, and Maddens Reference Wauters, Weekers and Maddens2010). The first candidates are most likely to obtain the most important executive functions (e.g., it is a standard practice that the first candidate of the largest political party becomes the mayor of the municipality) (de Moor, Marien, and Hooghe Reference de Moor, Marien and Hooghe2013). Hence it is important that women also obtain this key position. Given that this top position almost automatically guarantees a large number of preference votes, we expect the likelihood to vote for a female candidate to be larger when more women occupy the top position of the list in the electoral district.

H5:

In electoral districts with a high percentage of lists that have a woman at the top of the list, voters are more likely to vote for a female candidate.

In sum, the PR system and quota regulations are implemented at all levels of electoral competition in Belgium, and these are also the core of this study. The institutional provision of multiple preference votes allows us to gain an insight into how the use of voters of such provisions affects gender equality in legislative office. The quota regulations enable us to distinguish better between the ideology of the voter and the supply of women by the political party in the voters’ choice to vote for women. Given that these two characteristics are similar at the local and national level, we would expect similar results at the national level. Moreover, as a result of increased professionalization, national political parties take part in the elections in the overall majority of the municipalities (Wayenberg et al. Reference Wayenberg, De Rynck, Steyvers, Pilet, Hendriks, Lindström and Loughlin2010). Therefore, the electoral context is to a great extent similar at the local and national level.

Yet the local elections also have unique characteristics that make it an interesting case to study. It has been argued that women face more difficulties to become elected when the perceived importance of political office is higher (“law of minority attrition”) (Borisyuk, Rallings, and Thrasher Reference Borisyuk, Rallings and Thrasher2007). In this regard, local elections could offer a more favorable environment for the election of women (Borisyuk, Rallings, Thrasher Reference Borisyuk, Rallings and Thrasher2007). The stakes at local elections can be considered lower, as the local level of governance has only limited authority compared to the competences situated at the regional or national level (Deschouwer Reference Deschouwer2009). Therefore, local elections have been labeled second order elections (Heath et al. Reference Heath, McLean, Taylor and Curtice1999). However, in Belgium the local level elections are considered important and cannot be categorized as “second-order” (Marien, Dassonneville, and Hooghe Reference Marien, Dassonneville and Hooghe2015). In effect, voters use local voting motives and give similar importance scores to the local and national level (Lefevere Reference Lefevere, Dassonneville, Hooghe, Marien and Pilet2013). The closeness and visibility of the municipal level increases the importance of this level—with municipal competences such as town planning and the maintenance of road infrastructure or public order affecting everyday life of its residents. Therefore, we do not expect that differences in competences will strongly influence the likelihood to vote for women.

Descriptive figures on the representativeness of legislatures and voting behavior corroborate this reasoning. The representativeness of men and women in the local and national legislatures are of a similar magnitude with 36% female elected representatives in the 2012 municipal election compared to 39% at the 2010 national elections (See http://www.ipu.org). In addition, the number of voters casting a preference vote for at least one woman is similar at different levels of governance in Belgium with approximately 54% of the voters casting at least one preference vote for a woman at the municipal elections compared to approximately 55% of the voters at the regional elections (2012 Exit Poll data; Caluwaerts, Erzeel, and Meier, Reference Caluwaerts, Erzeel and Meier2013). Hence, there is no clear evidence that local elections would be a substantially better or worse context to gain office for women.

Yet we might theorize that the likelihood of same-sex voting differs between the local and national elections. The closeness of the local level to everyday life and the local candidates make the local elections a higher information context than the national elections. In effect, at the local level more preference votes are cast than at other levels of governance in Belgium (Wauters, Verlet, and Ackaert Reference Wauters, Verlet and Ackaert2012). Moreover, within the 2012 local elections the majority of the voters indicated that they voted for a candidate they personally knew (Marien, Dassonneville, and Hooghe Reference Marien, Dassonneville and Hooghe2015). This high-information context might decrease the use of same-sex voting as a voting cue. The context of personal contacts might also influence the electoral chances of women. Therefore, it is important to investigate same-sex voting in the local elections and to gain an insight in the effect of knowing a candidate personally on voting behavior.

DATA AND METHODS

Several Belgian universities (KU Leuven, ULB, UAntwerpen, Vrije Universiteit Brussel, UHasselt, UGent) collaborated in the organization of an exit poll in the context of the municipal elections in Belgium that resulted in the 2012 PARTIREP Exit Poll dataset (Dassonneville et al. Reference Dassonneville, Marien and Hooghe2012). Face-to face interviews were followed by a self-administered mock-ballot on which respondents were asked to cast their (preference) votes again. This innovative method of surveying vote choices was previously also employed in the Irish National Election Studies (Marsh and Sinnott Reference Marsh and Sinnott2008; McElroy and Marsh Reference McElroy and Marsh2010). This methodology is a particularly useful tool to record voting behavior including detailed information on preferential voting in an open list electoral system with a high number of preference votes. By means of these mock-ballots we gathered information on party choice and preference votes of the respondents. Moreover, these responses are not biased by media reports on the election outcome or by gaps in the memory of the respondents.

A multistage stratified sampling procedure was used. First, a random sample of municipalities was drawn based on region and on socioeconomic indicators of the municipalities.Footnote 1 Subsequently, a random sample of polling stations within the 40 selected municipalities was drawn. The number of polling stations in each municipality was determined by the number of inhabitants, while ensuring that all municipalities were covered by at least one team of interviewers. Interview teams (consisting of two students of the participating institutions who had received intensive training) were allotted to each polling station. In order to randomize the selection of respondents, interviewers were instructed to approach every fifth voter leaving the polling station and ask him/her to participate. The total response rate was 37.9% and 84.4% of these respondents also indicated their voting behavior on the mock ballot (N = 3,846). Within this sample, 973 voters indicated they casted a list vote. As the main interest of this study is on those respondents who have cast one or more preference votes, the respondents who have cast a list vote are not investigated.Footnote 2 As a result, the sample used in the analyses includes 2,873 respondents. In order to correct for small biases in the representativeness of the dataset, we weigh the respondents according to age groups, sex, and region.

Dependent Variable

Voters can use their preference votes in various ways in the Belgian flexible list system. They can choose to cast none, one, or multiple preference votes on candidates of one or both sex(es) within one party list. Given that the first position on the list is a highly visible position, it is also interesting to distinguish between casting one preference vote on the first candidate of the list and casting a preference vote for another candidate lower down the list. These options of preference voting result in a dependent variable with seven categories: Voting for only women included the options of (1) casting one preference vote on the first candidate on the list; (2) voting for one woman, not the first candidate on the list; and (3) voting for multiple women. Voting for only men included the options of (4) casting one preference vote on the first candidate on the list; (5) voting for one man, not the first candidate on the list, and (6) voting for multiple men. The final option was (7) voting for both men and women. This will allow us to sketch a rich and multifaceted picture of voting for women in Belgium, taking into account the complexity of this voting behavior.

Independent Variables

A first independent variable we include in the analysis is the sex of the respondent. In line with H 1 , we expect female voters to be more likely to vote for women than male voters (Dolan Reference Dolan1998). Next, political sophistication is expected to affect voting for women ( H 2 ). In the literature, political sophistication generally has two components: a cognitive component and a motivational component (Luskin Reference Luskin1990). We operationalize the cognitive component of political sophistication as the highest level of education a respondent completed. This variable includes three categories, namely lower education (i.e., completed primary education or lower secondary), middle education (i.e., completed higher secondary education), and higher education (i.e., completed tertiary education). We operationalize the motivation to get politically informed by including political interest in the local level in the analysis. This variable was measured on a scale from 0 (“no interest at all”) to 10 (“a lot of interest”). In line with H 3 , we include the ideology of the respondent measured on an 11-point scale with a value of 0 indicating a left-wing ideology and a value of 10 indicating a right-wing ideology.

At the voter level, we also include a number of control variables. Firstly, we include the age of the respondent in line with previous research (McElroy and Marsh Reference McElroy and Marsh2010; Holli and Wass Reference Holli and Wass2010). The results of previous studies are mixed documenting younger people to be more likely to vote for candidates of their own sex or finding no effect of age on gender-based voting behavior (McElroy and Marsh Reference McElroy and Marsh2010; Holli and Wass Reference Holli and Wass2010). We also control for the region in which the respondent lives (Flanders, Wallonia, or Brussels). This is a general control variable, controlling for differences between Belgian regions in degree of urbanization, particular electoral rules, and party system. It is also likely that casting a preference vote is influenced by whether one knows a candidate on the list personally, especially in municipal elections. Respondents were asked whether it was important that they knew a candidate personally in the decision to cast their preference vote(s) on an 11-point scale with a value of 0 indicating this was not important at all and a value of 10 indicating this was very important.

At the context level, we include district magnitude in line with H 4 . Given the PR system with rather large districts, and the possibility to vote for more than one candidate of the same list, we do not expect an effect of district magnitude on voting for female candidates. Finally, in line with H 5 , we include the percentage of lists in the electoral district that have a woman on the first place.

We conducted a multinomial multilevel logistic regression given that the dependent variable consists of seven categories that are nominal. Multilevel regression techniques are required given the hierarchical structure of the data (individuals nested in the electoral district) and the inclusion of individual and electoral district level variables (Hox Reference Hox2010).

RESULTS

First, we describe the frequency of voting for female and male candidates in the 2012 municipal elections in Belgium. We investigate whether there is a difference in the frequency of voting for male and female candidates and whether this can be explained by the characteristics of the voter (i.e., sex, political sophistication, ideological orientation). Next, we investigate the effect of the party on gender equality by investigating the amount of women taking the first place on the list. Subsequently, we present the results of a multilevel multinomial regression in which we try to explain voting for male and female candidates taking into account individual as well as context variables.

Descriptive Results

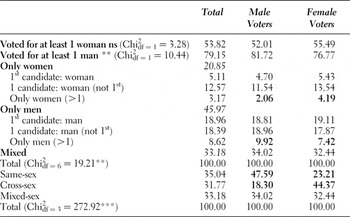

In the subsequent analyses, we focus on the respondents who voted for one or more candidates and analyze the distribution in preference votes for male and female candidates. The results of this analysis show that fewer respondents voted for female candidates than male candidates (Table 1). While 79.2% of the respondents voted for at least one male candidate, only 53.8% of the respondents voted for at least one female candidate. Despite the equal supply of male and female candidates resulting from the strict quota regulation, female candidates receive less preference votes than their male counterparts. There is no significant difference between female and male voters in the frequency of voting for female candidates. However, male voters vote significantly more for male candidates than female voters. Of the male respondents, 81.7% voted for at least one male candidate compared to 76.8% of the female respondents. We can conclude that same-sex voting is more common among male voters than among female voters, contrary to the emphasis in the theory on women supporting women at elections. This finding is not unique to the Belgian case, as previous research on the Finnish elections led to the same conclusion (Holli and Wass Reference Holli and Wass2010). It adds to the empirical evidence that calls attention to same-sex voting—not in terms of a gender affinity effect for women but in terms of men supporting men at elections, reinforcing their overrepresentation in legislatures. Voting for “at least one female candidate” is a broad category that can include voting for one female candidate, multiple female candidates, or female and male candidates. The results in Table 1 allow us to disentangle between these various options: one-third of the respondents voted for both male and female candidates (“mixed vote”), whereas two third of the respondents voted only for candidates of one sex. We can observe that it is much more common to vote for only male candidates than to vote for only female candidates. In effect, almost half of the respondents voted only for male candidates, while only one-fifth of the respondents casted their preference votes for only female candidates. Voters can choose how many preference votes they cast (within one list), and the results show that many voters cast only one preference vote. Approximately 20% of the respondents voted on one female candidate, whereas approximately 40% of the respondents voted on one male candidate (i.e., half of them on the first candidate on the list, half on another candidate on the list). Only 3.2% of the respondents casted multiple preference votes on female voters, whereas 8.6% of the respondents casted multiple preference votes exclusively on male candidates. There are significant differences between men and women in their voting behavior. Women are more likely to cast multiple preference votes on women candidates, while the amount of men engaging in this behavior is below average (contributing most to the chi2 value, respectively 24.1% and 22.6%). Likewise, male voters are more likely than female voters to cast multiple preference votes only on men (contributing 12.5% to the chi2 value). There appears to be a gender effect, but only for voters casting more than one vote.

Table 1. Frequency of voting for female and male candidates

Source: 2012 PARTIREP Exit Poll (n = 2,873; 40 municipalities).

Notes: Cells in bold contribute most to the Chi2. Only respondents who have cast at least one preference vote are included. Weight applied to correct for small differences in age, sex, and region. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

If we turn to the figures on “same-sex voting” (i.e., women voting for women; men voting for men), “cross-sex voting” (i.e., women voting for men; men voting for women) and “mixed-voting” (i.e., voting for male and female candidates), we see that the distribution of the different voting types in the total sample is relatively equal. There are some interesting differences with male respondents voting significantly more for candidates of the same sex and female respondents voting significantly more for candidates of a different sex. We can conclude that same-sex voting is more common among male voters than among female voters despite the emphasis in the literature on female voters supporting women. Despite the equal supply of male and female candidates, male as well as female respondents cast more often one or more preference votes on male than on female candidates.

Next to the sex of the voter, we also expect a relation between political sophistication and same-sex voting. We present the relation between voting behavior and education (Table 2) and political interest in the local level (Table 3). The results in Table 2 show that higher educated respondents are less likely to cast a vote on a candidate of the same sex and more likely to cast a mixed vote. This is in line with our expectation that respondents with lower levels of political sophistication are more likely to cast a same-sex vote. The number of respondents with higher education that casts a mixed vote is higher than expected if all groups had been equally likely to cast a mixed vote (contributing about 24% to the chi2 value). The number of respondents with secondary education casting a mixed vote is less than expected if all groups had been equally likely to cast a mixed vote (contributing about 23% to the chi2 value). We do not have specific expectations regarding the relation between political sophistication and voting for women in general. The results show that higher educated respondents are less likely to vote on only male candidates than respondents with secondary education (contributing approximately 10.5% to the chi2 value).

Table 2. Voting for women according to education

Source: 2012 PARTIREP Exit Poll.

Notes: Cells in bold contribute most to the Chi2. Weight applied to correct for small differences in age, sex, and region. *p < 0.001.

Table 3. Voting for women according to political interest

Source: 2012 PARTIREP Exit Poll.

Notes: Weight applied to correct for small differences in age, sex, and region. In the last column the results from Bonferroni post hoc tests are presented. Categories displayed in bold = level of political interest is higher among those voters; categories not in bold = level of political interest is lower among these voters.

Turning to political interest, the results in Table 3 are in line with expectations that voters with lower levels of political interest more frequently vote on candidates of the same sex. Respondents with a higher level of political interest vote more often on both male and female candidates (mixed vote) than respondents with lower levels of political interest. In effect, respondents that voted for candidates of both sexes have a mean value of 6.86 on the 0–10 point political interest scale, whereas respondents who voted only for women have a mean value of 5.48. Respondents who voted only on male candidates have a mean value of 5.66. Political interest in the local level relates to the number of preference votes too. Respondents who voted on multiple candidates (mixed or only one sex) have higher levels of political interest than respondents who voted for only one candidate. Nevertheless, the highest level of political interest is found among respondents who voted for both female and male candidates (mixed vote).

Turning to the ideological orientation of the voter, the results in Table 4 show no significant difference between the ideological orientation of the respondents and the likelihood to vote for women. Against our expectation, left-wing voters do not seem to be more inclined to vote for female candidates than right-wing voters.

Table 4. Voting for women according to ideological orientation

Source: 2012 PARTIREP Exit Poll.

Notes: Weight applied to correct for small differences in age, sex, and region. There are no significant differences between the categories.

Turning to the context level, we find that the gender distribution of the list is indeed biased with 25% of the first candidates in the sample being women. This is in line with the official statistics in Flanders that show that 20% of the first candidates were women. The quota regulations lead to an equal representation of women on the list and within the top two positions. Yet political parties predominantly implement the quota regulations by giving the first position to a male candidate and the second position to a female candidate. The results in Table 5 clearly show that women do not have the same chances as men to become elected. Additional analyses show that there are no substantial differences between left-wing and right-wing parties. Men—even within left-wing parties—predominantly take up the first key position of the list.

Table 5. Gender distribution of list positions and success rates in Flanders

Source: Official statistics 2012 local elections (307 municipalities). Authors’ calculations.

Multilevel Analysis

After investigating the bivariate relations for the individual variables, we turn to a multivariate analysis in which we include both individual variables and context variables (at the level of the electoral district). In Table 6 the results of the multinomial multilevel regression analyses are presented. The intraclass correlation of the baseline empty model is approximately 4%. Hence, most variation in voting for male and female candidates is situated at the individual level, not at the level of the electoral districts. Therefore, the context variables can offer only a limited explanation for the individual differences documented in voting for female candidates. By including the independent variables, our ability to predict voting behavior accurately improves as the log likelihood value decreases significantly compared to the empty baseline model. Moreover, we are able to explain a large part of the variance between the electoral districts as the intraclass correlation drops to 0.05%.

Table 6. Multilevel multinomial regression explaining voting for women

Source: 2012 PARTIREP Exit Poll (n = 2,581; 40 municipalities).

Notes: Only respondents who have cast at least one preference vote are included. Results of a multilevel multinomial logistic regression analysis. Reference category = mixed vote. Unstandardized coefficients are presented with standard errors between brackets. Information empty baseline model: Log likelihood = −4,435.589. Variancebaseline = 0.138 (0.055) ICC in % = 4.04. *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001. aNot the first on the list.

In line with the bivariate results, we see that women are more likely to cast multiple preference votes for female candidates than men but are less likely to cast multiple preference votes for male candidates. Further, political sophistication (both the cognitive and the motivational component) influences voting for female candidates. Respondents with tertiary education are less likely to vote only for male candidates than respondents with higher secondary education. More highly educated respondents are more likely to vote for female and male candidates than for only male candidates. In addition, respondents with tertiary education are also less likely to vote only for the first (male or female) candidate on the list compared to respondents with higher secondary education. In line with the bivariate results, we see that respondents with high levels of political interest are more likely to vote for both male and female candidates than to vote for candidates of one sex. Only voting for multiple women does not significantly differ from mixed voting.

To test whether women with lower levels of political sophistication vote more for women candidates (same-sex voting), we ran additional models taking same-sex voting as the dependent variable. These results, too, confirm the hypothesis that respondents with lower levels of political interest are more likely to vote for candidates of the same-sex even within this high-information context of the local elections. There is no difference between male and female voters: both sexes vote for candidates of the same sex when they have a lower level of political interest (confirming H 2 ). (See supplementary materials for results of the additional tests.)

To test H 3 , we added the ideological orientation of the respondents to the analysis. As indicated above, as a result of the quota regulation party differences in the number of female candidates are nonexistent. Therefore, we are better able than previous studies to investigate the effect of the ideological orientations of voters on the likelihood to vote for women keeping the supply of female candidates by left-wing and right-wing parties constant. The results show that respondents with a right-wing ideology are more likely to vote for the man who is the first candidate on the list than to vote for male and female candidates, yet there is no significant relation between ideology and other possible voting choices. We can conclude that the ideological orientation of individual voters does not impact (largely) the likelihood to vote for women. In general, left-wing voters counter the expectation that they are more likely to vote for women than right-wing voters.Footnote 3 Further, we see that respondents who indicate that knowing a candidate personally is an important voting motive are less likely to vote only for the first candidate on the list. In addition, they are less likely to vote only for women while there is no effect of knowing a candidate personally on voting only on men.

At the electoral district level, we find that district magnitude has no uniform effect on voting for female candidates. In electoral districts with a larger district magnitude, respondents are more likely to vote for one female candidate than to cast a mixed vote. Yet respondents are also more likely to vote for one male candidate (the first or another man on the list) than to cast a mixed vote. We can conclude that district magnitude rather affects the number of preference votes than the sex of the preferred candidate(s). This latter element is at odds with earlier findings in Finland (Giger et al. Reference Giger, Holli, Lefkofridi and Wass2014), but for logical reasons: the possibility in Belgium to cast multiple preference votes lowers competitiveness, which is considered the driving force behind the district magnitude effect on gender-based voting.

Finally, the more women who hold the first place of the list in an electoral district, the more likely voters will be to vote for a woman at the top of the list and the less likely they are to vote on a man at the top of the list. Even in quota systems, the supply of candidates proves to be important—not so much the number, but the position of women on the list matters. However, a larger supply of female candidates on the first position of the list neither increases the likelihood of voting for multiple women, nor decrease the likelihood of voting for only men.

CONCLUSIONS

The underrepresentation of women in representative assemblies is increasingly considered a problem in contemporary societies because of normative, substantive, symbolic, and efficiency reasons. The presence of women in representative assemblies is strongly influenced by the electoral system with proportional representation systems being more beneficial to the election of women than majority systems. However, the gender equality of the outcomes of various proportional systems also differs. A crucial factor in the analyses of the underrepresentation of women in legislatures is the study of voting behavior. Studying the provisions for preferential voting and how voters can (and effectively) use these provisions furthers our understanding of the descriptive representation of women.

We focused in this study on characteristics of the voter and the context that facilitate or hinder preference votes for female candidates. We rely on the results of a large-scale exit poll survey in which face-to-face interviews were combined with mock ballots. This innovative methodology is particularly useful to gain a better insight in the nature of preference votes in a flexible list system. As voters can cast multiple preference votes within one party list in Belgium, the use of a mock ballot during an exit poll allows the collection of extensive information on preference votes that is unbiased by gaps in the memory of the respondents and media reports on the election outcome.

We find a strong disparity in voting for female and male candidates: about one out of two respondents voted for at least one female candidate, whereas about eight out of ten respondents voted for at least one male candidate. We expected female voters to be more likely than male voters to vote for female candidates, yet same-sex voting appeared to be more common among male voters than female voters. This is in line with a recent study on the Finnish national elections (Holli and Wass Reference Holli and Wass2010) indicating that, despite the strong focus in the literature on women supporting women, men support men more in elections. Nevertheless, women voters are still more likely than men to cast preference votes exclusively for several female candidates.

Given that the local level is a very visible policy level close to the citizen, we expected the use of voting cues, such as the sex of the candidate, to be less relevant in this context. However, the results show that same-sex voting is more common among voters with lower levels of political sophistication. Women with lower levels of political interest were more likely to vote for women candidates while men with lower levels of political interest were also more likely to cast a vote for male candidates. Further, highly educated voters, compared to less educated respondents, are more likely to vote for both male and female candidates than for male candidates only. Respondents with higher levels of political interest are also more likely to cast this type of mixed vote than respondents with lower levels of political interest. Hence, the most sophisticated behavior seems not to limit oneself to candidates of one sex but to vote for multiple candidates of both sexes.

Further, this study of the Belgian case enabled us to better disentangle the ideology of the voter and the supply of female candidates. The quota regulations obligate all political parties to have an equal number of male and female candidates, making the party/sex overlap less problematic in Belgium. We find no evidence that ideology of individual voters is strongly related to voting for female candidates. Hence, the effect of ideology on voting for women might be the result of the unequal supply by parties (with left-wing parties presenting more female candidates) rather than the choice of left-wing voters to support female candidates more than voters with a right-wing orientation.

Personal contacts also affected voting behavior, as it proved to be able to foster support to candidates on less prominent positions on the list and increase the number of preference votes a voter casts. Yet the results seem to suggest that these personal contacts mainly relate to male candidates as knowing a candidate personally increases the likelihood of casting a mixed rather than an “all female ballot” but not than an “all male ticket.” We have no information on the sex of these personally known candidates, so this reasoning cannot be tested. Yet it is clear that the local context in which candidates are well known and in which these contacts serve as an important voting motive does not increase gender equality in legislatures.

Not only individual factors are expected to influence voting for women, but the context is also likely to affect the likelihood to vote for women (Giger et al. Reference Giger, Holli, Lefkofridi and Wass2014). As expected, district magnitude has a limited effect on the likelihood of voting for a female candidate in Belgium given that intraparty competition tends to be low as voters can cast multiple preference votes. Rather than the sex of the preferred candidate(s), district magnitude mainly affects the number of candidates one supports. Finally, the supply of female candidates plays an important role even in Belgium where the number of female candidates has to equal that of male candidates. Unlike previous research, the number of female candidates is not important (McElroy and Marsh Reference McElroy and Marsh2010), but their position on the ballot list has an effect on the propensity to vote for a woman. We find that when more women take the first place, voters are more likely to vote for the woman that holds this first position and less likely to vote on a man that holds this position. Yet, there is no spill-over effect: the likelihood of voting only for men does not decrease, nor does the likelihood of a mixed vote or a vote for multiple women increase in electoral districts with more women holding the first position of the list. Moreover, when looking at the lists, there is no clear difference between left-wing and right-wing parties: all parties predominantly put male candidates at the top of their lists. We can conclude that ideological orientation might influence gender equality on numerous aspects (e.g., proposing equality policies and quota regulations, etc.); it does not seem to be of great importance for the election of women in the Belgian PR flexible list system.

We can conclude that preferential voting can affect the descriptive representation of women substantially. By supporting female candidates, voters can further more gender equality in election outcomes. Moreover, the results of this study show that 55% of all preference voters cast only a vote for one candidate and that 24% of all preference voters cast only a vote for the candidate at the top of the list. Hence, voters can use the ability to cast preference votes even more to influence the election of female candidates. Further, political parties are also able to influence the election of women: by granting women (more and) better positions on the ballot list, including the top position, they can incite more voters to cast a vote for a female candidate. Though we found only limited differences between voting for female candidates in the different electoral districts, this does not mean that context factors are not important. Rather, the similarities between the different electoral districts are the likely result of the similarities between political parties in granting only a few women the top position on the list. While Belgium has strict quota regulations, this does not prevent the top of list from remaining male-dominated. It is exactly this position that is crucial for obtaining a large number of preference votes and gaining a seat in representative assemblies and the executives.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X16000404