Activism against youth involvement in the US sex trade has spanned the modern industrial era. In the early twentieth century, moral reformers campaigned against the “white slave trade.” Later, activists campaigned against “juvenile prostitution” in the 1970s and “commercial sexual exploitation of children” in the 1990s. In the early twenty-first century, campaigns against “domestic minor sex trafficking” attempted to reshape societal responses to youth involved in the sex trade by reframing young people as victims of exploitation rather than delinquents. These contemporary campaigns have resulted in new laws and public policies as well as new programs to assist youth exiting the sex trade. The success of these campaigns was due in large part to an ideologically diverse coalition of people supporting these changes, including feminists and evangelicals, conservatives and liberals. Participants in these campaigns also had disparate backgrounds, including social workers, those working in family courts, and self-identified survivors. Despite differing motivations, constituencies, and strategies, these varied actors formed a collaborative movement to fight for shared goals, such as safe-harbor laws intended to divert youth out of the criminal justice system and into social services (Baker Reference Baker2018). Critics, however, have argued that these reforms have created a social service bureaucracy that has mired youth in systems of restriction, regulation, and surveillance that are not responsive to their real needs (Lutnick Reference Lutnick2017; Musto Reference Musto2016; Showden and Majic Reference Showden and Majic2018).

In this article, I argue that across the waves of activism against youth involvement in the US sex trade from the 1970s to today, a common narrative has recurred, one that has drawn upon gendered and racialized notions of victimization. In the 1970s, the 1990s, and the 2000s, activists, politicians, and the media framed youth involvement in the sex trade as an “urban” problem invading suburban and rural communities, suggesting a racial subtext, and portrayals of the issue often focused on rescuing white girls victimized by black men. Echoing the nineteenth-century “white slave trade” narratives of foreign men luring white girls into prostitution and tapping into white supremacist narratives of black male sexual predation that fueled lynching in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, this narrative frame deployed gendered assumptions about the importance of (white) girls’ sexual innocence and racialized threats to their sexual purity. This frame was explicit in 1970s activism against juvenile prostitution, but it continued in a racially coded way in public discourses around commercial sexual exploitation and trafficking of youth in the 1990s and 2000s. In the 1970s, activists also exploited antigay sentiment in their campaigns against boys’ involvement in the sex trade, although attention to boys was almost entirely lacking in the later periods.

These racialized and gendered frames successfully gained public attention by exploiting white people's anxieties at historical moments when social change was threatening white male dominance and traditional sexual norms. They appealed to people anxious about social changes occurring in society: racial integration and immigration, youth rebellion, changing sexual norms, and increased female independence. They used neoliberal logics to justify building up the criminal justice system while neglecting the social conditions that made youth vulnerable to the sex trade. These narratives portrayed youth, particularly white girls, as helpless victims needing to be saved, not knowing any better, or not being able to help themselves. This narrative frame obscured state violence toward young people, especially youth of color. Instead, it appealed to the state for a stronger criminal justice response to trafficking and ignored the racist, sexist and heterosexist systems that made young people vulnerable to sexual exploitation. It also exacerbated the negative effects of the prison industrial complex on communities of color. Meanwhile, these narrative perspectives ignored the disproportionate representation and criminalization of black and brown girls in the sex trade, including trans girls and the large number of sex-trade–involved boys (Swaner et al. Reference Swaner, Labriola, Rempel, Walker and Spadafore2016, 61). Although it challenged male privilege in some ways, this activism largely recuperated white male dominance through gendered and racialized rescue narratives.

In this article, I begin by describing the history of racialized and gendered rescue narratives and the social conditions out of which these narratives arose in relation to youth involvement in the sex trade in the 1970s. I then provide examples of how these narratives manifested in each period. Using intersectional feminist theory, I argue that dominant rhetoric opposing the youth sex trade worked largely within neoliberal logics, ignoring histories of dispossession and structural violence and reinforcing individualistic notions of personhood and normative ideas about subjectivity and agency. Finally, I argue that this discourse has been part of ongoing racial and gender formation in American society that has been mobilized to obscure state violence against people of color and to bolster neoliberal economic systems and the prison industrial complex, systems that, in fact, make people more vulnerable to commercial sexual exploitation.

RACIALIZED AND GENDERED RESCUE NARRATIVES

Rescue narratives have a long history, articulated in a range of contexts. In “Two European Images of Non-European Rule” (Reference Asad and Asad1973), Talal Asad argued that colonizers used discourses centered on rescuing colonized people from themselves to justify colonial rule in Middle Eastern and African societies. Encapsulated in Gayatri Spivak's famous quotation, “White men are saving brown women from brown men” (Reference Spivak, Nelson and Grossberg1988), this paternalistic rescue narrative presumes to be acting in the best interests of the less powerful by restricting their freedoms and responsibilities, but it has, in fact, often been used to effectively mobilize and justify interventions by dominant populations into the lives of less powerful peoples and nations. More recently, Lila Abu-Lughod (Reference Abu-Lughod2002) and Ann Russo (Reference Russo2006) have shown how rhetoric about saving oppressed Afghani women was used to justify the invasion of Afghanistan. Critics of the current global antitrafficking movement have argued that movement discourses rely on white savior narratives and civilizing missions (Baker Reference Baker2013, Reference Baker2014; Hua Reference Hua2011; Kempadoo Reference Kempadoo2015).

The narrative of white men saving white women from brown men has been just as common. This rescue narrative has constructed notions of sex and race (i.e., heroic white men as protectors of vulnerable white femininity from violent men of color), and it has been used to justify oppressive gender, racial, economic, and political systems. Imperial captivity narratives about interracial sexual assault by men of color against white women justified white men's conquest of indigenous lands, their harsh measures of rule, and the suppression of revolt (Woollacott Reference Woollacott2006). Historically in the United States, white people used this narrative in the nineteenth-century to justify as white men protecting white women from black men, but it was really about maintaining political and economic dominance (Giddings 2008). In the late nineteenth-century “white slavery” narrative, white men and women framed themselves as protectors of (usually) white girls from immigrant men and men of color (Doezema Reference Doezema2000). The term “white slavery” was used by policy makers, advocates, and the media in stories about white women allegedly being forced into prostitution by immigrant men or men of color. This discourse generated a moral panic growing out of anxieties about female sexuality and autonomy, as well as race and immigration, and resulted in laws restricting women's mobility in the interest of protecting them (Doezema Reference Doezema2000). In the United States, Congress passed the White Slave Traffic Act of 1910, otherwise known as the Mann Act, which prohibited the interstate transportation of women for “immoral purposes” but was in fact used to criminalize nonnormative, particularly interracial, consensual sexual behavior (Langum 1994).

The 1970s revival of activism against youth involvement in the sex trade was fueled by similar social and political changes that destabilized white male power. The civil rights movement, the sexual revolution, the women's movement, and the gay liberation movement challenged racial segregation as well as traditional sexual and gender norms. New laws such as Title IX, which prohibited sex discrimination in education, knocked down barriers to women entering traditionally male-dominated fields such as law and medicine, and federal affirmative action initiatives opened doors to women in male dominated blue-collar trades such as construction and mining. Meanwhile, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the birth control pill in 1960, and the Supreme Court declared a fundamental right to contraception and abortion, which for the first time ensured women a modicum of control over their reproductive lives, bolstering their access to education and employment. Rates of premarital sex by teenagers increased significantly in the 1970s, while young people were more likely to believe that sex before marriage was a legitimate choice. Conservatives and feminists expressed anxiety about the increasing sexualization of women and girls in popular culture. Members of the feminist group Women Against Pornography dubbed the “eroticized images of little girls which now flourish in every form of the media” as the “Lolita syndrome,” referencing Vladimir Nabokov's book Lolita about a prepubescent girl who seduces an adult man, which at the time was being produced as a Broadway play (Women Against Pornography n.d.). Meanwhile, the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act greatly increased the number of immigrants coming into the United States, particularly from Latin America and Asia. Social anxieties growing out of these seismic changes and the destabilization of white male dominance likely contributed to the revival of a racialized and gendered rescue narrative about juvenile prostitution in the 1970s.

In subsequent decades, with the rise of the Internet, increased single parenthood, the successes of the LGBT rights movement, and spikes in racism and xenophobia stoked by 9/11, racialized and gendered antitrafficking narratives became a mechanism for recuperating white male dominance and traditional sexual norms. This discourse has used stories of racialized threats to girls’ sexual innocence to justify increased law enforcement funding and criminal prosecutions that have disproportionately harmed communities of color. In the following sections, I trace how racialized and gendered rescue narratives permeated public discourse on US youth involvement in the sex trade in the 1970s, the 1990s, and the 2000s.

1970s “MINNESOTA PIPELINE” NARRATIVE

In the 1970s, news stories galvanized concern about the increasingly visible phenomena of juvenile prostitution by presenting a racialized narrative of exploitation. Echoing a deeply entrenched historical narrative of dangerous black masculinity and white female vulnerability, juvenile prostitution was framed as an “urban” problem that was invading white, middle-class communities in suburban and rural areas—black men from cities luring young, innocent and naïve white girls to the city and then forcing them to become prostitutes. News articles often focused on white, middle-class runaway girls from suburban and rural areas, who were portrayed as sexually innocent and naïve girls duped by black pimps. This narrative frame obscured the fact that black and brown girls, including trans girls, were disproportionately involved in the sex trade and were more likely than white cisgender girls to be arrested and jailed (Swaner et al. Reference Swaner, Labriola, Rempel, Walker and Spadafore2016; Curtis et al. Reference Curtis, Terry, Dank, Dombrowski and Khan2008). Through the media and political discourse, the problem of juvenile prostitution was socially constructed using racist, sexist, and heterosexist stereotypes to stoke moral outrage.

The media and antiprostitution activists argued that pimps were forcibly transporting girls from the Midwest to New York City to be sold in sex trade; this narrative was dubbed the “Minnesota pipeline.” The racialized framing of juvenile prostitution was explicit in many articles in the 1970s. A 1972 front-page article in the Tribune, for example, quoted a local police officer commenting on shifts in the composition of prostitutes in Minneapolis over time: “In 1967, a negligible percentage of those arrested for prostitution were minors. So far this year, more than 25% of the prostitutes arrested have been juveniles. … Young, white runaways may have become a bigger target for pimps, most of whom are black, because fewer black women are going into prostitution … the racial composition of prostitutes in Minneapolis has gone from being 60% to 70% black to being 80% white” (Schmidt 1972). A 1976 WNBC news documentary, Requiem for Tina Sanchez, focused on the “Minnesota strip,” a section of Eighth Avenue between 40th and 50th streets described as a “tawdry section of New York City where pimps make money exploiting the bodies of the young … hundreds of mid-western middle-class girls, mostly white, many under 16, runaways,” which the narrator describes as “a new breed of prostitutes” (Lynch Reference Lynch1976, 1:40 minutes). The film described the girls as coming from small, out-of-state towns, as it panned down a street past a church building (2:13 minutes). The film portrayed black men pimping young, naïve, and vulnerable white girls, who left home because of neglectful mothers, while middle-aged white men tried to save the girls. Noting that “nearly all the pimps are black; nearly all the out-of-town [girls] are white,” a 1975 New York Times article quoted a New York City police officer Warren McGinniss saying, “The kid has been brought up not to have any racial bias and she's bending over backward to show she's not prejudiced when she's accosted by this nicely dressed, sweet-talking, perfumed black man; she's so conscious that she shouldn't put him down that she forgets she's being picked up by a street hustler” (Morgan Reference Morgan1975, 34). Contrary to the claims of the “Minnesota pipeline” narrative, research at the time concluded that the issue was overblown and that there was little evidence of the transportation of girls from Midwest to New York City (The Enablers 1978; Illinois Legislative Investigating Committee 1980).

Activists, policy makers, and the media in the 1970s sometimes used the explicitly racialized language of “white slavery” from the early twentieth century. For example, a 1972 Time magazine article was titled “White Slavery, 1972.” In a 1979 press release announcing the creation of a shelter for prostituted youth, the New York City-based Odyssey Institute, quoted its founder Judianne Densen-Gerber describing the men who exploit children in prostitution as “true white slavers.” A 1980 report by the Illinois Legislative Investigating Commission also used the phrase “white slavery activist” in referencing juvenile prostitution (Illinois Legislative Investigating Commission 1980, 2). These narrative frames reveal how racial anxieties may have fueled some of the concern about juvenile prostitution in the 1970s.

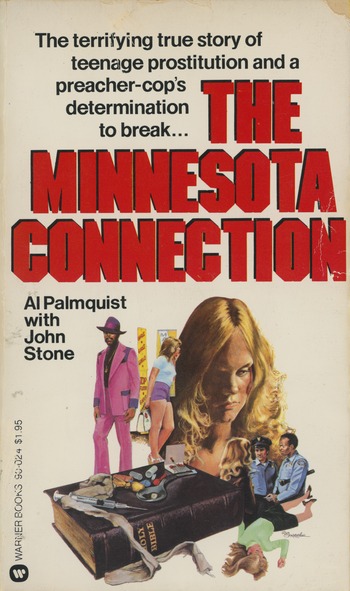

The most extreme version of this narrative appeared in a book called Minnesota Connection, written by a former Minnesota police officer and minister named Al Palmquist and published in Reference Palmquist and Stone1978. The book was a first-person account of Palmquist's campaign to stop the transportation of teenage girls from Minnesota to New York's commercial sex trade. The book claimed to tell the story of the “white slave trade between the midwestern cities and New York” and how one preacher/cop was “winning the fight against teenage white slavery” (Palmquist 1978). Palmquist focused on young white girls, as young as 14, exploited by African American pimps. The cover drawing as well as photographs within the book made these racial dynamics clear. On the front of the book, a collage depicted the bowed head of a girl with long blond hair and a sad facial expression, the figure of a black man in a pink suit with a brimmed hat, the girl scantily clad next to a sign reading “Girls Girls Girls,” a syringe and drugs on top of a Bible, the girl speaking to two police officers, and the girl splayed out on ground, passed out or dead (Figure 1). Inside the book were photographs of girls murdered by pimps.

Figure 1. Cover of Al Palmquist's 1978 book The Minnesota Connection (New York: Warner Books).

Palmquist repeatedly described the girls as blonde or Scandinavian (Palmquist 1978, 37, 46, 47, 89, 90, 91). Ironically, he called black men's alleged exploitation of white girls “slavery” and “bondage” (11, 50, 52, 92). Several scenes of graphic sexualized violence portrayed pimps beating and torturing girls (52, 57). Palmquist argued that the “average prostitute” was an unwilling participant: “Trapped, forced and threatened with torture or death, she has little chance to escape” (50), a claim disproved by research at the time (The Enablers, 1978). Palmquist repeatedly described the girls as coming from “fatherless” homes, as having weak or inattentive fathers, and as being in need of “discipline” and responsible male control over their lives (11, 45, 53, 55, 68), which solicited nostalgia for traditional patriarchy. Palmquist portrayed himself as very macho, “strapping on a gun,” driving a “fast sports car,” and crashing in the door of a pimp (112, 114). He declared that his mission was to “search and expose, rescue and restore” (49). He gave a detailed narrative of traveling to New York twice to find girls on the “Minnesota strip” to return home, but when he found few girls and none willing to go with him, he blamed police corruption, media publicity, and discomfort with his religious orientation (133–135, 145).

Palmquist's exploits received extensive media coverage (Kohl Reference Kohl1978; Rawson Reference Rawson1977; “Teenaged Harlots Get Help” 1977). He and two young survivors spoke at many community forums in the Midwest and made television appearances on the Phil Donahue Show and the P.T.L. Club. The Minnesota pipeline narrative reverberated broadly across the culture. In 1978, there was a Broadway musical—Runaways—about juvenile prostitution, with a song titled, “The Minnesota Strip: Song of a Child Prostitute” (Swados Reference Swados1978). On May 2, 1980, ABC aired a television movie, Off the Minnesota Strip, about a teenage runaway's struggles to readjust to home and family life after living as a prostitute in New York City (Johnson, Reference Johnson1980). This racialized rescue narrative appealed to a white population anxious about changing race, gender, and sexual norms in society.

Although most concern at the time focused on girls in the sex trade, concern about boys emerged as well, against a backdrop of an increasingly visible gay rights movement at the time (Kaye Reference Kaye2003, 42–46). In fact, homophobia infused public discourses relating to the prostitution of boys. Media coverage and political discussions of child pornography involving boys in the late 1970s often linked “homosexuality” with child sexual abuse and targeted the gay community more generally. William Kelly of the Illinois Gay Rights Task Force, in written testimony submitted to Congress in 1977, objected to the “repeated insinuations and sometimes overt allegations by some of the news media and some state and local officials that gayness is in any way synonymous with any form of child abuse” (United States Senate Judiciary Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency 1977, 68). Absent, however, was the focus on nonwhite aggressors that characterized stories involving girls. The harm to white girls was racialized (i.e., they were targeted by black men), whereas the harm to boys was sexual (i.e., they were targeted by gay men). Both narratives mobilized dominant racial, gender, and sexual social norms to define the harm done. To address concerns about boys, Congress unanimously passed the Protection of Children Against Sexual Exploitation Act of 1977, which made child pornography a federal crime and expanded the Mann Act, which outlawed the interstate transport of minors for prostitution, to boys.

Activism against juvenile prostitution in the 1970s spurred the development of social services for youth in the sex trade, which were cut back in the 1980s when Ronald Reagan came into office as part of his attempts to shrink government and lower taxes. At the same time, Reagan escalated the war on drugs and built up the prison industrial complex, which increasingly ensnared young people involved in the sex trade. By the mid-1990s, the large number of young people incarcerated for prostitution spurred a new movement against the US youth sex trade, which sought to reframe young people as victims rather than delinquents (Baker Reference Baker2018, 66, 110). Concern about boys was absent, but a racialized and gendered discourse of girls involved in prostitution was revived, this time reframed as “commercial sexual exploitation of children.” This discourse continued to obscure the disproportionate victimization and criminalization of black and brown girls involved in the US sex trade.

INVADING “AMERICA'S HEARTLAND” IN THE 1990s

In contrast to the 1970s, public discourse on juvenile prostitution in the 1990s focused on the exploitation of youth in Southeast Asia, not on juvenile prostitution in the United States. Newspapers and magazines reported dramatic stories about Cambodian parents selling their young daughters for money to buy television sets or young boys servicing Western tourists on Thai beaches (see, e.g., Branigin Reference Branigin1993). Politicians and activists working to create a federal antitrafficking law focused mainly on international sex trafficking outside and into the United States. The first iteration of the TVPA in 2000 referenced only foreign migrants to the United States (perhaps reacting to the large number of immigrants in the United States as a result of immigration reform that began with the 1965 Immigration and Naturalization Act). This led to numerous raids of “Asian massage parlors” to find trafficking victims. However, very few individuals were certified as victims, and most women detained were simply deported. In 2005, the TVPA was amended to include “domestic minor sex trafficking,” which led to increased policing efforts against black male “pimps” (Brennan Reference Brennan2008).

When the media did cover child prostitution involving American youth, it was framed in ways similar to how it had been framed in the 1970s. The issue received the most attention when it was portrayed as impacting white, middle-class girls from the suburbs. Activists, police, policy makers, and journalists decried a “new trend”: “the movement of organized prostitution into smaller cities and suburbs” and into “America's heartland” (Clayton Reference Clayton1996b; Johnson Reference Johnson1992; Knickerbocker Reference Knickerbocker1996). Activists warned that the problem was growing and that girls in prostitution were getting younger and younger. Similar to the 1970s concern about girls being trafficked along the “Minnesota pipeline,” concern in the 1990s centered on girls being trafficked along the “Pacific circuit,” from Vancouver to Los Angeles (Clayton Reference Clayton1996d). This concern was linked to the advent of the Internet and the growing availability of pornography at the click of a button. Conservatives and some feminists condemned the increasing sexual objectification of women and girls in American popular culture and worried about the vulnerability of girls to sexual exploitation. Concern about the “Lolita syndrome” of the 1970s evolved in the 1990s into concern about the “Pretty Woman syndrome”—young girls lured by glamorized images of prostitution in the media, such as Julia Roberts’ portrayal of a prostitute who wins over a millionaire john and marries him in the 1990 movie Pretty Woman (Clayton Reference Clayton1996a).

A Christian Science Monitor series in 1996 that ran right before the First World Congress on the Commercial Sexual Exploitation of Children in Stockholm reported that child prostitution in the United States was spreading from big cities to suburbs and small towns. For example, a 1996 Christian Science Monitor article quoted Lois Lee of the Los Angeles-based organization Children of the Night saying “The circuit used to be the big cities… Now the circuit has switched to the suburbs. The prostitution subculture has become very, very mobile” (Knickerbocker Reference Knickerbocker1996). An August 30 article titled “Sex Trade Lures Kids From Burbs” quoted antiprostitution activist Frank Barnaba saying, “Pimps used to recruit in the city. But they discovered it's much easier to work the burbs. The kids are naïve, materialistic, and vulnerable to the pimp's message” (Clayton Reference Clayton1996c). Barnaba described working with youths recruited from “the shopping malls and fast-food restaurants of the Midwest—heartland places like San Antonio, Cleveland, or Wichita, Kansas” (Clayton Reference Clayton1996d), and several articles quoted him saying that girls came to New York from Connecticut, Florida, Massachusetts, Texas, Oklahoma, California, and from Cleveland, Minneapolis, Poughkeepsie, and Westchester County, Long Island. Ericka Moses of Minneapolis-based feminist antiprostitution organization PRIDE was quoted saying, “A lot of the time naïve suburban girls come to the city to hang out and have fun, and within six months they're on the streets prostituting” (Clayton Reference Clayton1996c). These characterizations of the issue were strikingly similar to those in media coverage of the issue in the 1970s.

Other newspaper coverage in the 1990s followed the more explicitly racialized tropes that appeared in mainstream coverage of the issue in the 1970s. Several stories focused on blonde, midwestern girls. For example, a 1992 New York Times story about the Paul and Lisa Program began with a story of a “blonde Mid-westerner” whom the program had successfully transformed from a girl dressed in a “miniskirt, fishnet stockings and six-inch heels” into a girl described as having a “shy polite manner” and who “could have easily passed for a cheerleader” (Weizel Reference Weizel1992). An August 19, 1999 Minneapolis Star Tribune article reported that the Midwest was a “major recruiting center” because “blue-eyed, blonde girls are considered valuable,” according to one police sergeant, and because midwestern girls “have a higher degree of vulnerability” and are “a little more naïve” than girls elsewhere, according to a social worker (Bentley and Meryhew Reference Bentley and Meryhew1999). This article repeated the stereotypical portrayal of female vulnerability and abuse: “Recruitment involved a predictable interplay of a young girl's vulnerability, a pimp's smooth talking and then, physical and emotional abuse” (Bentley and Meryhew Reference Bentley and Meryhew1999). These narratives repeated those that circulated in the 1970s, except that boys were largely absent from the 1990s media stories.

By the end of the decade, a powerful antitrafficking movement was pushing for federal legislation to address international sex trafficking. Advocates for youth in the sex trade supported this legislation in the hope that the law would also help US youth. The proposed legislation defined sex trafficking to include inducing anyone under the age of 18 to engage in a commercial sex act, without regard to whether there was force, fraud, or coercion. These advocates lobbied members of Congress by bringing youth to the Capital to talk with them. But according to Laura Barnitz, who as part of Youth Advocates Program organized the US Campaign Against the Commercial Sexual Exploitation of Children to lobby for the antitrafficking law, advocates for US youth had a hard time convincing members of Congress that US youth in the sex trade were victims, which she believed was due at least in part to race. As a result, when advocates were attempting to convince conservative members of Congress of the importance of this issue, they deliberately selected young white women to talk about their experiences of exploitation.Footnote 1 The Trafficking Victims Protection Act (TVPA) became law in 2000 and, while the Act defined trafficking to include US youth in the sex trade, the funding authorized by the law to address trafficking was only available to groups working with international victims of sex trafficking, primarily abroad. Calling attention to this double standard soon became a central tactic of activists seeking to expand the TVPA in the 2000s to provide funding to organizations working to help US youth in the sex trade (Baker Reference Baker2018).

THE “OUR GIRLS” NARRATIVE IN THE 2000s

At a congressional hearing in 2005 titled, Exploiting Americans on American Soil: Domestic Trafficking Exposed, a major theme was the spread of the commercial sexual exploitation of youth from poor kids in the city to wealthy, white children in the suburbs and rural areas. Class was addressed more explicitly than race, but both were driving themes of the hearing. The survivor chosen to testify, Leisa B., was a young white woman who described herself as coming from an upper-middle-class family in Atlanta. Citing a Reference Estes and Weiner2002 study on juvenile prostitution in the United States by Estes and Weiner of the University of Pennsylvania, conservative Representative Christopher Smith (Republican, New Jersey), who convened the hearing, noted that while children from poor families were at higher risk of commercial sexual exploitation, he emphasized that “most of the street children encountered in the [Estes and Weiner] study were Caucasian youths who had run away from middle-class families” (Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe, 2005, 3). Frank Barnaba explicitly emphasized how the problem was spreading from the city into the wealthy suburbs. He testified, “Traffickers are no longer demons of the big city. They are infiltrating the small towns of America,” then explained that 75% of youth served by his program were from “upper-middle-class families living in rural areas,” whom he described as “more vulnerable to exploitation and less streetwise than their city peers” (33–34). He told the story of working with a “valedictorian from a very, very prominent Connecticut town” and warned that “pimps [are] coming right into their homes” (33–34). Several of the speakers, including Representative Smith and antiprostitution activist Norma Hotaling, emphasized that it was “our citizens” and “our girls” who were being exploited. Hotaling described how pimps lured girls, emphasizing that “it's any girl, it's our girls” (33–34). References to race were more oblique than in the 1970s and 1990s but still strongly present. There was a racial subtext to Barnaba's depiction of domestic sex trafficking as originating in the city and spreading to the wealthy suburbs. The survivor who testified, Leisa B., did not identify the race of her “pimp,” as she described him, but referenced him hiring a drug dealer to drive her and four other girls around because “it would look hot if there was five white girls and a black man driving a nice truck” (23). Several speakers acknowledged that girls from all racial and ethnic backgrounds were targeted by pimps, yet the hearings focused on white, upper-middle-class girls.

The racialized themes that trafficking was targeting “our children” and the fear of “lost innocence” continued to reverberate in congressional hearings, media coverage, and activist discourses later in the decade. Coded racial appeals were repeated throughout a congressional hearing in September of 2010. Representative Smith emphasized in his testimony, “These are our daughters. These are our children” (US House Judiciary Subcommittee on Crime, Terrorism and Homeland Security 2010, 21). Representative Mike Quigley (Democrat, Illinois) repeated the common refrain that child sex trafficking not only happened in “third-world countries” or to poor people but that it affected “the nicest neighborhoods”:

Child sex slavery, child sex trafficking, prostitution of children … you would like to think or unfortunately imagine this would be in some Third World country, or at least not in nice neighborhoods. But I will tell you, you can go out in Lakeview, one of the nicest communities in the city of Chicago and the nicest areas that you would ever want to live in, you will see the vans out there of social service agencies trying to find the kids, runaway kids who are exposed to—who are vulnerable to these offenses right there in some of the nicest neighborhoods … the people who are committing these offenses … are not far away. (4)

Quigley's testimony made explicit the concern for the sexual exploitation of middle-class and upper-middle-class youth.

The reactionary tone of this hearing was expressed in repeated calls for extreme punishment for traffickers. Representative Ted Poe (Republican, Texas) suggested that lynching might be an appropriate response to trafficking when he said, “The traffickers are the filth of humanity and they are criminals. And as one Texas Ranger friend of mine called these individuals, he said, when you see one, Judge, get a rope” (16). Before serving in Congress, Poe had been a district judge in Harris County Texas. Poe repeated this threat to “get a rope” later in the hearing in response to the testimony of African American survivor and service provider Tina Frundt (217). Representative Smith emphasized the “huge and escalating crisis of child sex trafficking in the United States” and called for “very long prison sentences, including up to life imprisonment itself” for traffickers (21). Another witness, activist Linda Smith of the antitrafficking organization Shared Hope International, condemned the “men who buy [children's] innocence,” calling for the “full penalty called for in the law,” reflecting her organization's position that the government should prosecute men who buy sex from minors with sex trafficking.

Ironically, considering this racialized discourse, speakers throughout the hearing repeatedly described child sex trafficking as slavery, including National Center for Missing and Exploited Children's CEO Ernie Allen, who said, “This is truly 21st century slavery” (2, 4, 6, 9, 138). Nicholas Sensley, Chief of Police, Truckee Police Department, Truckee, California, made an explicit parallel to the transatlantic slave trade: “From the street level we can attest that what is going on in this domestic minor sex trafficking is, in fact, an act of slavery. Where the problem exists is that there is not the emphasis in responding to this problem of slavery that we saw some 200 years ago” (145). He characterized domestic minor sex trafficking as “an atrocity that is being perpetrated against our children” (145). Scholars have criticized this appropriation of black suffering for “reducing the memory and imagery of slavery to objects that are compatible with the anti-trafficking narrative, without regard for the ongoing black liberation struggle” and in fact “articulated in the logics that underpinned racial chattel slavery in the first place” (Beutin Reference Beutin2017; see also Bravo 2007). Despite using the language of slavery, many activists and policy makers have ignored the disproportionate victimization and criminalization of youth of color in the sex trade.

The media in the 2000s echoed this racialized discourse. For example, in 2003, Newsweek ran a story titled, “This Could Be Your Kid,” by Suzanne Smalley about suburban “teen prostitutes” who sold sex for designer clothes. The story featured a “cute, blond and chatty” teenage girl named Stacey from Minnesota, who was lured from the Mall of America where she liked to hang out after school. Stacey, described as living with her parents in an “upscale neighborhood” with “good grades in high school and plans to try out for the tennis team,” was typical of a growing number of “teen prostitutes,” warned Smalley (Reference Smalley2003). The article characterized the problem as mainly involving girls, who were getting younger, were increasingly likely to come from middle-class homes, and were subjected to increasing violence from “pimps.” The story quotes a Minneapolis detective, saying, “‘Everyone thinks they are runaways with drug problems from the inner city. It's not true. This could be your kid.’” Smalley quoted a counselor from the Paul and Lisa Program (a Connecticut-based organization providing services to youth in the sex trade), who said, “People say, ‘We're not from the ghetto.’ The shame the parents feel is incredible.” The racially coded language of “inner city” and “ghetto” was similar to language from the 1970s.

This narrative also appeared in documentary films and survivor memoirs. The most widely distributed films about the prostitution of youth were three feature-length documentary films: Very Young Girls in Reference Schisgall and Alvarez2007 (Schisgall and Alvarez), Playground in Reference Spears2009 (Spears), and Tricked in 2013 (Wells and Wasson Reference Wells and Wasson2013). Very Young Girls, produced by Girls Educational and Mentoring Services (a New York City-based organization providing services to girls in the sex trade), circulated widely with community groups and at colleges, as well as playing on Showtime. Playground and Tricked were available on Netflix. These three films foregrounded the stories of survivors. While race was not discussed explicitly in any of the films, Playground and Tricked focused primarily on the stories of white girls, whereas Very Young Girls focused mostly on black girls. The “pimps” portrayed in all three films were African American. The “rescuers” were largely white people. Very Young Girls’ focus on voices and experiences of girls of color challenged the dominant narrative of victimized white girls, but otherwise the film conformed to the story of black men violating girls’ innocence.

Similarly, many widely circulated survivor memoirs portrayed the issue in racialized and gendered ways. For example, Theresa Flores’ The Slave Across the Street in Reference Flores and Wells2010, Holly Austin Smith's Walking Prey in Reference Smith2014, and Barbara Amaya's Nobody's Girl in Reference Amaya2015 echoed the dominant narrative of sex trafficking with stories of middle-class or upper-middle-class white girls from “intact” families lured into the sex trade by men of color. These stories deployed the racialized notion of white female innocence threated by men of color. Activists, politicians, and the media often portrayed the issue in terms of protecting the innocence of young girls. For example, Congress held a hearing in 2014 titled “Innocence for Sale: Domestic Minor Sex Trafficking” and the FBI called its campaign to target the youth sex trade “Innocence Lost National Initiative” and used a promotional image of a pigtailed white girl (see Figure 2). In these ways, a racialized and gendered rescue narrative lived on well into the 2000s.

Figure 2. Promotional image from the Federal Bureau of Investigation's “Innocence Lost” national initiative.

COUNTERNARRATIVES

While gendered and racialized rescue narratives persisted over time, some counternarratives emerged in the 2000s. Advocacy groups such as Girls Educational and Mentoring Services, the Human Rights Project for Girls, Young Women's Empowerment Project, and Minnesota Native Women's Research Center resisted mainstream discourses of white girls lured into prostitution by black men, albeit in very different ways. These counternarratives focused on the victimization of girls of color in prostitution, and they raised attention to the role of white men as buyers of sex from youth. Rather than calling for rescue, they called for empowerment of youth and for addressing the systemic factors that made youth vulnerable to sexual exploitation.

In 2010, for example, Rachel Lloyd, the founder and director of Girls Educational and Mentoring Services (GEMS), called out the racial dynamics of domestic minor sex trafficking while testifying at a congressional hearing before the US Senate Judiciary Subcommittee on Human Rights and Law. At the hearing, titled In Our Own Backyard: Child Prostitution and Sex Trafficking in the United States, Lloyd drew attention to the disparity between how US and international victims of trafficking were treated, suggesting that race may be a factor:

As a nation, we've graded and rated other countries on how they address trafficking within their borders and yet have effectively ignored the sale of our own children within our own borders. We created a dichotomy of acceptable and unacceptable victims, wherein Katya from the Ukraine will be seen as a real victim and provided with services and support, but Keisha from the Bronx will be seen as a ‘willing participant,’ someone who's out there because she ‘likes it’ and who is criminalized and thrown in detention or jail. (US Senate Judiciary Subcommittee on Human Rights and Law 2010, 15)

Lloyd contrasted law enforcement's sympathetic treatment of the presumably white Katya from the Ukraine with the judgmental and punitive treatment of the presumably African American Keisha from the Bronx, condemning this double standard. In a book, Girls Like Us (Lloyd Reference Lloyd2011), about her own experience in prostitution and her work with girls in prostitution at GEMS, Lloyd delved into the structural vulnerabilities of youth of color such as poverty, failing schools and child sex abuse, and the need to address these vulnerabilities to end youth involvement in prostitution. On the other hand, Lloyd did not apply this structural analysis to the behavior of the black men involved in facilitating youth involvement in the sex trade (e.g., the pimp depicted in Very Young Girls). Furthermore, despite raising up the voices and experiences of girls of color, GEMS in other ways reinforced dominant gendered narratives of girlhood innocence, as in the promotional image for the film Very Young Girls (Figure 3). The film featured teenagers, despite the title of “very young girls” and the promotional image portraying a young child's legs with Mickey Mouse sneakers.

Figure 3. Promotional image for Girls Educational and Mentoring Services (GEMS) film Very Young Girls.

Another advocate for exploited youth, Withelma T. Ortiz Walker Pettigrew of the Human Rights Project for Girls (HRPG), raised the issue of race at a 2014 congressional hearing before the House Judiciary Subcommittee on Crime, Terrorism and Homeland Security titled Innocence for Sale: Domestic Minor Sex Trafficking in 2014. Herself a survivor and African American, Pettigrew testified about the harsh treatment she received in the criminal justice system. At one point in her testimony, she suggested the role that race may have played in how she was treated. The police, she testified, “always wanted to detain me and my pimp, both people of color, instead of focusing on the buyers who were adults and primarily White. No one seemed to care about them” (US House Judiciary Subcommittee on Crime, Terrorism, and Homeland Security 2014, 17–18). Pettigrew called on Congress to provide services to youth trafficking survivors and to end the criminal prosecution of youth for prostitution. With the Georgetown Law Center on Poverty and Inequality and Ms. Foundation for Women, the HRPG produced an important report that focused in part on girls incarcerated for prostitution titled The Sexual Abuse to Prison Pipeline: The Girls’ Story (Saar et al. Reference Saar, Epstein, Rosenthal and Vafa2015). The report argued that girls in the juvenile justice system, especially girls of color, were disproportionately victims of sexual violence, that girls’ behavioral reaction to sexual abuse and trauma was criminalized, and that the juvenile justice system typically failed to address, and often exacerbated, the trauma that caused girls to be there. The jailing of victims of sex trafficking was a prime example. The report argued that the juvenile justice system was ill-equipped to identify and treat violence and trauma at the root of victimized girls’ arrests and recommended better mechanisms for identifying and treating trauma in the child welfare system.

Native American girls were the focus of another important advocacy group, the Minnesota Native Women's Research Center (MNWRC), which conducted research into the commercial sexual exploitation of Native American women and girls in Minnesota and published a report in 2009 titled Shattered Hearts, documenting the prevalence and patterns of commercial sexual exploitation of Native American women and girls in Minnesota, as well as the factors that facilitated entry and the barriers to exiting the sex trade. The report highlighted how the Native American history of colonization, including anti-Indian attitudes and stereotypes, the boarding schools, assimilation policies, involuntary sterilization, the Indian adoption policy, and generational trauma made Native American females particularly vulnerable to entering the sex trade (Pierce Reference Pierce2009, 5–13).

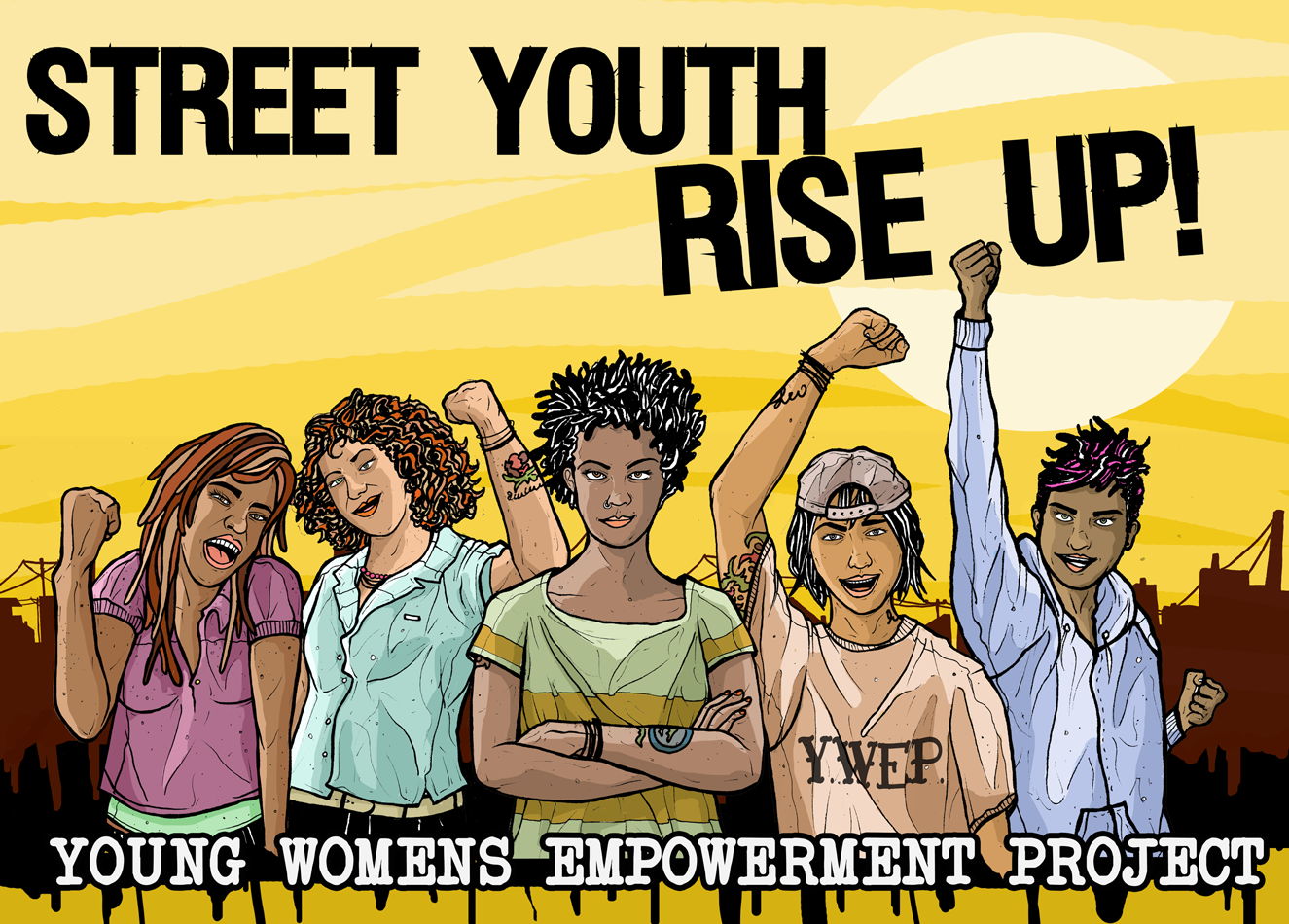

While GEMS, the HRPG, and the MNWRC all promoted the voices and perspectives of girls of color with experience in the sex trade, these organizations have collaborated with people in the criminal justice and social welfare systems, hoping to improve the treatment of girls, but likely contributing to the ongoing criminalization of black men. In contrast to these reformist approaches, the Chicago-based Young Women's Empowerment Project (YWEP) pursued a liberation politics focused on supporting youth outside of mainstream institutions. Run by young people engaged in the street economy, YWEP conducted participatory action research revealing that adults in the criminal justice, foster care, and health-care systems abused and neglected these youth (2012). YWEP resisted the pathologization of youth involved in the sex trades, and instead focused on the failures of the systems that were supposed to be serving them. They used a harm reduction approach, which assumed that youth know what is best for themselves, arguing that youth are not helpless victims and that “girls do what they have to do to survive” (2009). YWEP's “Street Youth Rise Up” campaign included participatory action research into the negative experiences youth have with institutions and a street march and speak out in Chicago on September 30, 2011, to announce the report with 75 youth and 15 adult allies. YWEP also formed the Chicago Street Youth in Motion, a city-wide task force for street-based youth that developed a “Street Youth Bill of Rights” outlining youth rights in four areas: health care, education, police, and social services. Finally, YWEP launched a “Healing in Action” campaign that taught girls how to take care of themselves outside of institutional health care through workshops and a magazine. The image used in publicity for their “Street Youth Rise Up!” campaign shows how YWEP embraced an empowerment narrative of youth agency and strength (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Image from the Young Women's Empowerment Project's (YWEP's) “Street Youth Rise Up!” campaign.

Moreover, GEMS, HRPG, MNWRC, and YWEP all had very different approaches to the issue of youth involvement in the sex trade. While GEMS was a service-based organization that worked closely with the criminal justice system and other social service providers, YWEP was a youth collective that worked to expose police and healthcare provider abuse of youth and to empower youth to take care of themselves outside of these systems. HRPG was a national advocacy organization based in Washington, DC, whereas MNWRC was a service provider working closely with Native American women and girls in the Midwest. All of these organizations resisted racialized rescue narratives and called attention to the systemic failures that made youth vulnerable to entering the youth sex trade in the United States, but these organizations varied in the degree to which they worked within mainstream systems and utilized dominant narratives of victimization (Baker Reference Baker2018, 102).

Current research is revealing that young people in the sex trade are much more heterogeneous than the dominant racialized rescue narrative suggests. Many are LBGTQ youth and cisgender males (Dank, Yahner et al. Reference Dank, Yahner, Madden, Bañuelos, Yu, Ritchie, Mora and Conner2015). Many do not have facilitators and are not directly forced to participate in trading sex (Lutnick Reference Lutnick2016). A study by scholars at the Center for Court Innovation and John Jay College found that only 16% of youth involved in prostitution in New York City had a facilitator (Curtis et al. Reference Curtis, Terry, Dank, Dombrowski and Khan2008). As a result, policies that respond to the dominant racialized rescue narrative by focusing on law and order criminal justice system responses to the youth sex trade are unlikely to be effective. Senior research scientist at Research Triangle Institute International Alexandra Lutnick argues that the needs of youth forced into prostitution by third parties are very different than the needs of youth engaging in survival sex, and that antitrafficking laws often focus on the former group, even though the latter group is likely larger. Programs that require identification of a facilitator to receive assistance, she argues, fail to serve the latter group. Lutnick illustrates the racialized rescue narrative in her critique of a California police training video that focused “exclusively on young cisgender women who have a third party forcing them to trade sex” and “where the young cisgender women are provocatively dressed and are being exploited by a person of color until police officers come in and save them” (Lutnick Reference Lutnick2016, 91–92). This contextual frame, which she calls “rescue porn,” can be harmful by reinforcing the stereotypes that make many victims invisible such as LBGTQ young people, young cisgender men, or young people who are not in an exploitative dynamic with a third party.

Furthermore, the policing practices and expanded services available because of the TVPA and the antitrafficking movement do not always benefit youth, argues Jennifer Musto (2016). The public–private antitrafficking collaborations among law enforcement and advocates, private social service organizations, and faith-based groups facilitate punitive treatment, surveillance, and social control of youth seen as vulnerable to trafficking, says Musto. Law enforcement officers engage in a “switch-up” (i.e., treating girls as offenders, then victims, or some a combination of both) to achieve their priority goal, which is to criminally prosecute adults who facilitate youth involvement in the sex trade (Conner Reference Conner2016; Musto Reference Musto2016). Enhanced police efforts to fight trafficking has also had a negative impact on men of color. Concern about domestic minor sex trafficking has resulted in heightened policing of men of color and longer prison sentences, contributing to the expansion of the criminal justice system in the United States, with all its attendant harms to communities of color (Alexander Reference Alexander2012; Brennan 2016).

CONCLUSION

Across the decades of the late twentieth century and into the twenty-first century, racialized and gendered rescue narratives recurred in strikingly similar ways, functioning as a racial dog whistle. Scholar Ian Haney López has defined dog whistle politics as “coded racial appeals that carefully manipulate hostility toward nonwhites,” such as “blasts about criminals and welfare cheats, illegal aliens and sharia law in the heartland” (López Reference López2014, ix). These appeals communicate messages to a targeted audience about threatening nonwhites, although the cloaked language hides the racial character of the overture to some listeners, argues López (5). In the 1970s, the 1990s, and in the 2000s, condemnations of the youth sex trade were framed as an “urban” problem invading white middle-class communities and the “heartland” and affecting “our daughters,” suggesting a racial subtext. Portrayals of the issue often focused on white girls victimized by African American men, echoing nineteenth century “white slave trade” stories and lynching narratives. These frames appealed to whites anxious about social change and justified the build-up of the criminal justice system and the neglect of poor communities of color (Alexander Reference Alexander2012). The bitter irony was that these frames often occurred side by side with the characterization of the youth sex trade as a form of “modern-day slavery” (Maynard Reference Maynard2015). Furthermore, they obscured the disproportionate victimization and criminalization of youth of color in the sex trade.

This dominant racialized and gendered rescue narrative deploys neoliberal logics that individualize social problems and obscure state responsibility for perpetuating structural inequities that make youth vulnerable to involvement in the sex trade. The youth sex trade is framed as a criminal justice problem, and the state, particularly the criminal justice system, is framed as the rescuer of youth. Congress provides generous funding to government initiatives such as the FBI's Innocence Lost National Initiative, which conducts cross-country raids to arrest pimps and traffickers, and to local law enforcement for training, investigation, and prosecution, while only modest funding is provided for direct services to youth and nothing is done to address the social conditions that perpetuate the youth sex trade such as high rates of child poverty, failing schools, and lack of living wage jobs for youth. The dominant narrative of “slaves, sinners and saviors” (Baker Reference Baker2013; Davidson Reference Davidson2005, 4) leaves little room for addressing the complex reality of youth involvement in the sex trade. Instead, this discourse is part of the ongoing project of racial and gender formation in US society that has been mobilized to obscure state violence against people of color, bolster neoliberal economic systems, and expand the prison industrial complex to reinforce white male supremacy in US society.