On February 12, 2018, the National Portrait Gallery unveiled the official portraits of Barack and Michelle Obama. The event provided a national opportunity to reflect on the historic nature of the Obamas’ tenure in office and what their status as the first African American first family meant for the American public. In her remarks, Michelle Obama emphasized the symbolism of her presence for young African American women, stating, “I'm also thinking about all the … girls and girls of color, who in the years ahead will come to this place, and they will look up, and they will see an image of someone who looks like them hanging on the wall of this great American institution.”Footnote 1 This was not the first time Michelle Obama had commented on the symbolic importance of her family's presence in the White House. In an interview for Essence magazine shortly before departing the White House, she noted, “I think when it comes to black kids, it means something for them to have spent most of their life seeing the family in the White House look like them … It matters” (Lewis Reference Lewis2016).

Others have also evoked the language of symbolism and empowerment when speaking about Michelle Obama's tenure as first lady. Speaking at the 2012 BET Honors, Maya Angelou commented, “She is a lady, and by that I do not mean in money or education, or even power, but she has grace. She is meaningful to all women” (Thompson Reference Thompson2012). Political commentator and political scientist Melissa Harris-Parry noted, “Every time she flawlessly performs her role as first lady, just by being who she is, she shows how extraordinary and exceptional we [African American women] are” (Thompson Reference Thompson2012).

The foregoing comments are notable for their invocation of Michelle Obama as a political symbol. The common theme throughout these statements is that Michelle Obama was an important symbol in American politics and that beyond any of her activities as first lady, her presence provided meaning to particular groups of Americans. As these quotes also illustrate, various commentators have argued that Michelle Obama held special meaning for multiple groups and subgroups in American politics. The quotes we select are but a small sample of the commentary surrounding Michelle Obama during her time as first lady and beyond, yet they are illustrative of a broader point. Much of the commentary surrounding Michelle Obama used the language of symbolism, arguing that her presence was politically meaningful for women, African Americans, and/or African American women, depending on the context. Commentary surrounding the meaning of Obama's first ladyship was especially potent given her status as the nation's first African American first lady. Indeed, the legacy of Michelle Obama will no doubt be tied to her unique status in American history, and the language of symbolic representation will likely continue to be used in discussions of her legacy.

Yet in order to fully evaluate this legacy and Michelle Obama's capacity to serve as an empowering political symbol, a systematic examination of public opinion toward the first lady must occur. In this article, we evaluate public opinion toward Michelle Obama, specifically asking whether and how she was able to provide symbolic representation to women, African Americans, and African American women. While previous studies have examined the role of gender and race in evaluations of the first ladies generally, and of Michelle Obama more specifically, an understanding of how the intersection of Michelle Obama's race and gender influenced evaluations of her as first lady is lacking (Elder and Frederick Reference Elder and Frederick2017; Knuckey and Kim Reference Knuckey and Kim2016). In this article, we address not only the extent to which race and gender influenced evaluations of the first lady but also how the intersection of these descriptive identities influenced public opinion more broadly. Drawing on the literature on intersectionality, we argue that in order to fully understand public opinion toward Michelle Obama, the intersection of her race and gender must be taken into account, along with the intersection of race and gender among members of the public. In doing so, we also contribute to the growing body of literature analyzing public opinion toward presidential and presidential candidate spouses, as well as the literature on public opinion toward minority women.

Using data from the Black Women in America survey, we examine how race, gender, and the intersection of race and gender influenced opinion toward Michelle Obama. Using this data source allows us to examine facets of public opinion not found in previous research on the first ladies. Specifically, we are able to examine public response to Michelle Obama's signature initiative, the “Let's Move” campaign. Further, we are able to examine the degree to which survey respondents believed that Obama improved perceptions of African American women in America. Though we also use traditional favorability ratings found in most studies of presidential spouses, we believe the inclusion of these additional dependent variables sheds additional light on public opinion toward Michelle Obama and helps contextualize her ability to serve as a meaningful political symbol for the American public. We find that, like other first ladies, Obama generally enjoyed high levels of public approval during her time in the White House, and she was generally insulated from the politics of the administration, though baseline evaluations of Michelle Obama were influenced by individual partisanship and ideology.

Using a wider range of indicators than previous studies on public opinion toward the first ladies, we provide a more nuanced understanding of public opinion toward Michelle Obama. We find that while African Americans viewed Michelle Obama more favorably than white Americans, there were no significant differences in favorability based on gender for either racial group. When we shift emphasis to issues related to policy, specifically Michelle Obama's Let's Move campaign, we find that African Americans were more attentive to the policy than whites, but also that white women were more attentive than white men. Finally, we find that Michelle Obama was uniquely positioned to serve as a symbol for African American women and that her presence in the White House inspired African American women to view their group identity more positively. As we note in our conclusion, these improvements in group affect may have potential downstream effects for participation, efficacy, and political ambition among African American women.

Previous studies on public opinion and the first ladies that have included Michelle Obama are notable for their lack of attention to the intersection of race and gender. Similarly, because of the severe underrepresentation of African American women in American politics, studies of public opinion toward African American women in politics have been necessarily limited in their scope and context. As a high-profile political figure, Michelle Obama represents a particularly salient case to test how the intersection of race and gender influences public opinion toward political actors. Thus, understanding how the intersection of race and gender shaped evaluations of Michelle Obama represents an important advance in the literatures on the first ladies, public opinion, and our understanding of public reactions to prominent black women in American politics.

FIRST LADIES AND POLITICAL REPRESENTATION

In order to fully understand the legacy of Obama's first ladyship and her ability to serve as a political symbol, she must be understood in the broader context of the first ladies. Popular narratives and media accounts often describe first ladies as apolitical actors. Indeed, most first ladies attempt to stay above partisan politics, often choosing to emphasize noncontroversial valence issues (Eksterowicz and Sulfaro Reference Eksterowicz and Sulfaro2002). To some degree, it has become an informal expectation that the first lady will promote a cause and that this cause will be noncontroversial (Knickrehm and Teske Reference Knickrehm, Teske, Watson and Eksterowicz2003; Parry-Giles and Blair Reference Parry-Giles and Blair2002; Sulfaro Reference Sulfaro2001). When first ladies do engage in inherently partisan activities or take policy stances on nonvalence issues, they often incur backlash from the American public (Mughan and Burden Reference Mughan, Burden and Weisberg1995) and receive higher levels of negative press coverage (Erickson and Thomson Reference Erickson and Thomson2012; Scharrer and Bissell Reference Scharrer and Bissell2000; Zeldes Reference Zeldes2009). Michelle Obama's Let's Move campaign, which was aimed at eradicating childhood obesity, and her advocacy for greater access to higher education are emblematic of the type of noncontroversial valence issues associated with a traditional view of the first ladyship.

As objects of public opinion, first ladies generally enjoy a fair amount of insulation from public reaction to the actions undertaken by presidential administrations. Cohen (Reference Cohen2000), for example, finds no evidence that public approval of the first lady is influenced by presidential approval ratings, nor does approval of the first lady influence public favorability toward the president (see also Mughan and Burden Reference Mughan, Burden and Weisberg1995; but see Simonton Reference Simonton1996). On the campaign trail, numerous studies have found that candidate spouses can play an important role in shaping public affect toward candidates and that candidate spouses exert some influence on vote choice (Burrell Reference Burrell2001; Mughan and Burden Reference Mughan, Burden and Weisberg1995, Reference Mughan, Burden, Weisberg and Box-Steffensmeier1998).

In general, the spouses of presidential hopefuls enjoy a positive relationship with the American public, and this relationship is increasingly pronounced once a candidate spouse assumes the role of first lady. As Burrell, Elder, and Frederick (Reference Burrell, Elder and Frederick2011, 165) note, “as the public came to know them better, most spouses experienced a general increase in the percentage of Americans who viewed them favorably.”Footnote 2 Though greater familiarity also leads to increases in the number of Americans who disapprove of candidate spouses and first ladies, typically more Americans approve of the first lady than disapprove of her (Burrell Reference Burrell2000; Burrell, Elder, and Frederick Reference Burrell, Elder and Frederick2011; Cohen Reference Cohen2000; Elder and Frederick Reference Elder and Frederick2017). The widespread popularity and support enjoyed by many first ladies seems to suggest that first ladies have the potential to rise above partisan politics and to serve as a unifying symbol for the American public.

Despite the temptation to view the first lady as an apolitical actor, some scholars argue that the office itself is inherently political and that the politicization of the office of the first lady has increased over time. Parry-Giles and Blair (Reference Parry-Giles and Blair2002) argue that the first lady is a political figure because the activities she undertakes—no matter how neutral they appear on their face—occur in a political space. Over time, first ladies have evolved into increasingly political actors, particularly on the campaign trail. In recent elections, MacManus and Quecan (Reference MacManus and Quecan2008) observe, first ladies are often strategically sent to battleground states for campaign rallies, and they are used in a manner not dissimilar to vice presidential candidates.

Though first ladies often enjoy high levels of support from the public, research suggests that Americans filter their opinions of the first lady through a partisan lens (e.g., Campbell et al. Reference Campbell, Converse, Miller and Stokes1966). While studies on individual opinions toward first ladies are sparse, most empirical examinations reveal that partisanship is a significant predictor of attitudes toward the first ladies—with Democrats being more favorable to Democratic first ladies and Republicans being more favorable to Republican first ladies (Burrell Reference Burrell2001; Burrell, Elder, and Frederick Reference Burrell, Elder and Frederick2011; Elder and Frederick Reference Elder and Frederick2017; Knuckey and Kim Reference Knuckey and Kim2016; Mughan and Burden Reference Mughan, Burden and Weisberg1995; Sulfaro Reference Sulfaro2001; Tien and Miller Reference Tien, Checchia, Miller and Whitaker1999), though the effects of partisanship are less pronounced for first ladies than they are for approval of presidents (Mughan and Burden Reference Mughan, Burden and Weisberg1995). As Sulfaro (Reference Sulfaro2007, 498) succinctly notes, “First Ladies are not, in fact, removed from partisan politics, despite occasional claims to the contrary.” Indeed, Knuckey and Kim (Reference Knuckey and Kim2016) note that opinion toward the first lady has become increasingly divided along partisan lines, consistent with increases in political polarization.

Taking the view that first ladies are political figures, the question becomes, to what extent are first ladies able to provide representation to the American public? Though first ladies may have the potential to influence policy outcomes and priorities, they are vested with no formal policy-making power. In this sense, their ability to provide substantive policy representation is limited. Despite these limitations, first ladies may be able to provide symbolic representation to many Americans. Pitkin (Reference Pitkin1967, 92) defines symbolic representation as the extent to which a representative “stands for” those they represent. In order for a representative to “stand for” others, as Pitkin defines the concept, the represented must assign some meaning to the representation they receive. This meaning may be captured by observing the attitudes and behaviors that representatives evoke from the represented. Schwindt-Bayer and Mishler (Reference Schwindt-Bayer and Mishler2005) conceptualize symbolic representation as the “feeling of being fairly and effectively represented.” Research on gender and politics and on race and ethnicity politics has measured symbolic representation in myriad ways, including political trust, feelings of efficacy, approval, and favorability. For scholars in this vein, typically the question is whether political figures who share a gender, race, or ethnicity with those they represent are better able to evoke these feelings than political actors who do not share these descriptive characteristics.

Though the descriptive-symbolic link is frequently examined in the context of elected officials and the constituencies that elect them, the relationship between descriptive and symbolic representation can manifest outside of an electoral context. Though not selected by the public, nonelected officials can nonetheless provide meaningful symbolic representation to individuals. In a cross-national study, Liu and Banaszak (Reference Liu and Banaszak2017) find that women's presence in executive cabinets can provide symbolic benefits and stimulate women's political participation. Morgan and Buice (Reference Morgan and Buice2013) suggest that women's presence in nonelected executive positions can help to shape broader attitudes about women's political roles. In the U.S. context, Badas and Stauffer (Reference Badas and Stauffer2018) find that in the absence of ideological congruence, U.S. Supreme Court nominees are able to elicit support from Americans who share a nominee's gender, race, or ethnicity.

This body of research suggests that the ability for political actors to “stand for” others extends far beyond electoral contexts. Just as nonelected officials are able to provide symbolic representation, so, too, should first ladies. The increasing political nature of the position, coupled with the political lens through which first ladies are often viewed, makes it increasingly likely that first ladies will be able to evoke political feelings from the American public. The tenure of Michelle Obama as first lady provides an especially compelling context to examine this question, given her status as the first African American first lady. This makes it possible for us to examine the degree to which the first lady served as a political symbol for women, racial minorities, and minority women.

GENDER AND EVALUATIONS OF FIRST LADIES

The office of the first lady is an inherently gendered political space (Duerst-Lahti Reference Duerst-Lahti, Borrelli and Martin1997; Winter Reference Winter2000). Gendered expectations for presidential spouses, coupled with institutional constraints and structures, have created expectations in the minds of many Americans about how the first lady should behave within the administration. Indeed, Americans express higher levels of support for first ladies who embody more traditionally feminine traits and adhere to a more supportive rather than active role in their husbands’ administrations (Burrell, Elder, and Frederick Reference Burrell, Elder and Frederick2011). Hillary Clinton, for example, faced severe backlash and public scrutiny when she took an active role in health care policy. While some studies have examined how the public reacts to first ladies who do or do not embrace a traditional role and themes (e.g., Burrell, Elder, and Frederick Reference Burrell, Elder and Frederick2011), others have examined the extent to which public opinion toward the first ladies differs based on the gender of survey respondents (Sulfaro Reference Sulfaro2001).

Though the literature on public evaluations of first ladies is sparse, scholars who have studied public opinion toward presidential spouses have found that first ladies may have the potential to provide symbolic benefits to American women. Sulfaro (Reference Sulfaro2007) finds that, in general, women exhibit higher levels of support for first ladies than men. Burrell, Elder, and Frederick (Reference Burrell, Elder and Frederick2011) find mixed evidence for the idea that first ladies serve as meaningful symbols to women. In their analysis of affect toward the spouses of presidential candidates, they find that women were more likely to support Tipper Gore and Michelle Obama. For all other candidate spouses in the period analyzed (2000–2012), the authors find no evidence of similar gender affinity effects. In a follow-up study, Elder and Frederick (Reference Elder and Frederick2017) again find evidence of gender affinity effects in the case of Michelle Obama, but they do not find a similar relationship between gender and Ann Romney's favorability. The effects of gender on approval for potential first ladies is emblematic of some form of symbolic representation, as some candidate spouses are able to elicit positive reactions from potential constituents. Sulfaro (Reference Sulfaro2007) alludes to the potential that first ladies serve as a political symbol for American women, but few studies examine this proposition in depth.

To some degree, the link between gender and support for the spouses of presidents and presidential candidates may be rooted in partisanship. As noted earlier, Burrell, Elder, and Frederick (Reference Burrell, Elder and Frederick2011) find effects in the context of Democrats Gore and Obama but find that gender has no effect on support for other candidate spouses (see also Elder and Frederick Reference Elder and Frederick2017). Scholars have long observed a gender gap in partisan affiliation, with women being more likely to belong to the Democratic Party and men to the Republican Party (Box-Steffensmeier, De Boef, and Lin Reference Box-Steffensmeier, De Boef and Lin2004; Kaufmann and Petrocik Reference Kaufmann and Petrocik1999; Norrander Reference Norrander1999). To some extent, the propensity of women to view Democratic first ladies more favorably may be rooted in a shared partisanship. Yet even after controlling for factors such as ideology and partisanship, Elder and Frederick (Reference Elder and Frederick2017) find that women continue to be more likely to view Michelle Obama favorably, suggesting that gender effects are not solely the product of shared partisanship. While Republican first ladies—and potential first ladies—such as Barbara Bush, Laura Bush, and Ann Romney do not similarly enjoy higher levels of support among women, Elder and Frederick (Reference Elder and Frederick2017) suggest that their gender may nonetheless be insulating them from negative evaluations they might otherwise incur from women because of their partisanship.

Though the link between women's support for first ladies may be partially due to shared sex, first ladies—and candidate spouses more generally—are often used by administrations and campaigns in gendered ways. First ladies often discuss their husbands in the context of family and tend to emphasize familial themes in their speeches and appearances (Duerst-Lahti Reference Duerst-Lahti, Carroll and Fox2014; Elder and Frederick Reference Elder and Frederick2017; Elder and Greene Reference Elder and Greene2016). Events such as Family Circle’s cookie recipe contest have become traditions of modern presidential elections, further associating themes of domesticity with presidential spouses. Further, first ladies are often the ones dispatched to meet with women's groups (Wright Reference Wright2016). Campaigns clearly see gendered opportunities to deploy candidate spouses. Laura Bush, for example, was used heavily by the Bush campaign as part of its “The ‘W’ Stands for Women” initiative during the 2000 campaign (Carroll Reference Carroll, Carroll and Fox2005). Michelle Obama similarly made appeals to women rooted in her experiences as a wife and mother (Elder and Frederick Reference Elder and Frederick2017). These examples suggest that campaigns and administrations see utility in deploying the first ladies to engage women constituents. Perhaps because of their appeal to a shared sex and a common set of group interests, the first ladies may be seen as an especially important position in attempts to engage with, and win, the votes of women.

While not all first ladies have embraced a traditional role or made explicit appeals to women, Michelle Obama certainly did. During her 2008 Democratic National Convention speech, Michelle Obama emphasized her gender and familial themes, stating, “I come here as a sister … I come here as a wife … I come her as a mom … and I come here as a daughter.”Footnote 3 On the campaign trail, and later as first lady, Obama was quick to talk about issues related to family and often talked about the struggles to maintain some semblance of normalcy for her daughters in the White House (Elder and Frederick Reference Elder and Frederick2017). In her 2012 convention speech, she referred to herself as “mom-in-chief” and noted that she viewed her role as mother as her most important job (Duerst-Lahti Reference Duerst-Lahti, Carroll and Fox2014; Elder and Frederick Reference Elder and Frederick2017; Elder and Greene Reference Elder and Greene2016).

Beyond her emphasis on family and motherhood in speeches and campaign activities, Michelle Obama embraced a traditional role as first lady (Burrell, Elder, and Frederick Reference Burrell, Elder and Frederick2011; Elder and Frederick Reference Elder and Frederick2017). During her time in the White House, Michelle Obama championed causes related to healthy living and combating childhood obesity. These efforts were most pronounced through her creation of the White House organic vegetable garden and the Let's Move campaign. When promoting Let's Move, she often spoke from her perspective as a mother and talked about future generations of American children. As Wright (Reference Wright2016) notes, “Michelle Obama always approached the topic of healthcare from the perspective of a mom, of a family, of someone who cares about the generation of kids.” Beyond her initiatives related to healthy living, Michelle Obama engaged in other traditionally feminine issue areas such as education, including holding a celebratory gathering for the nation's high school counselor of the year. These activities, coupled with Michelle Obama's emphasis on her gendered roles as wife and mother, may make her an especially appealing political figure to American women. In the sections that follow, we examine the extent to which Michelle Obama was able to engender support from American women and the extent to which this support differed from that of men.

RACE AND EVALUATIONS OF FIRST LADIES

While public evaluations of first ladies are clearly shaped by gender and gendered considerations, race also plays an important role in understanding how Americans evaluate first ladies. Indeed, in the case of Michelle Obama, race is a particularly salient factor to consider. Previous scholarship suggests that race can significantly shape evaluations of potential first ladies in some contexts. Burrell, Elder, and Frederick (Reference Burrell, Elder and Frederick2011), for example, find that African Americans held significantly lower evaluations of Laura Bush than comparable whites, and Hillary Clinton enjoyed relatively high levels of support among black Americans (Sulfaro Reference Sulfaro2007). Clinton's popularity among the African American community may have been partly attributable to her husband's moniker as the “first black president.” These findings suggest that in some contexts, public attitudes toward the first lady can be racialized.

While race can play a role in public opinion toward the first lady in general terms, we expect this will be especially true in the case of Michelle Obama. As the nation's first African American first lady, Obama served as an important symbol for the African American community. Scholars of public opinion and political behavior have long noted displays of in-group loyalty among African Americans, with black Americans being particularly supportive of candidates and elected officials who share their racial identity (Dawson Reference Dawson1994; Huddy and Carey Reference Huddy and Carey2009; Philpot and Walton Reference Philpot and Walton2007; Reese and Brown Reference Reese and Brown1995; Sigelman and Welch Reference Sigelman and Welch1984; Tate Reference Tate1994). This trend is most commonly ascribed to feelings of linked fate (e.g., Dawson Reference Dawson1994) among racial minorities and the perception of a common set of group interests. Though exceptions can exist in cases of black officials who are perceived to be undercutting black interests, in general, African Americans tend to provide particularly high levels of support to black candidates and officials (Huddy and Carey Reference Huddy and Carey2009).

Though group interests no doubt play a role in African American support for African American candidates and officials, to some extent, this support is also likely rooted in feelings of group pride. This pride is particularly likely to manifest when candidates or public officials represent historic firsts for African Americans. Huddy and Carey (Reference Huddy and Carey2009) point to the historic nature of Barack Obama's nomination and black support during the Democratic primaries in 2008. Mansbridge and Tate (Reference Mansbridge and Tate1992) similarly point to the high profile and historic nature of Clarence Thomas's nomination to the U.S. Supreme Court in their discussion of black support for Thomas.Footnote 4 Michelle Obama similarly represents a historic first for the African American community, as the nation's first presidential spouse of color. Indeed, Elder and Frederick (Reference Elder and Greene2016) find that African Americans had significantly higher positive views of Michelle Obama in 2012 than whites did, and these levels of favorability far surpassed African American favorability ratings for Ann Romney.

The historic nature of the Obama family was often commented on during the 2008 and 2012 presidential campaigns, as well as throughout the Obama administration. During the 2012 reelection campaign, Michelle Obama commented on her historic first ladyship, saying, “You know what, I think that because Barack and I are here[,] I do think kids today see a bigger world and understand, and it's not so threatening” (Thompson Reference Thompson2012). Given the historic nature of the Obama presidency, and the salience of race in discussions related to Michelle, we expect that African Americans will be especially likely to view Michelle Obama favorably, to follow her activities and policy initiatives, and to view her as a positive symbol for the African American community. While previous studies have examined the role of race in public evaluations of Michelle Obama (e.g., Elder and Frederick Reference Elder and Frederick2017; Knuckey and Kim Reference Knuckey and Kim2016), these studies have been largely confined to the context of the 2008 and 2012 elections, and they have focused only on favorability ratings. We expand this research by examining the role that race plays in public evaluations of Michelle Obama in nonelection years and by considering a wider array of outcomes that tap into the concept of symbolic representation.

MICHELLE OBAMA AND THE INTERSECTION OF RACE AND GENDER

Though the literature on public opinion toward first ladies is sparse, scholars studying the topic have found that both gender and race play a role in public opinion formation toward the first lady. In the case of Michelle Obama specifically, previous scholarship has found that women tended to be more favorable toward the first lady than men during both the 2008 and 2012 election cycles and that African Americans had much stronger evaluations of Michelle Obama than comparable whites. Yet research analyzing public opinion toward Michelle Obama has often neglected to examine how the intersection of her race and gender might have influenced public opinion. In other words, Michelle Obama's status as both an African American and a woman may have meaningfully shaped public opinion toward her, and this may be distinct from the gendered and racialized effects found in other studies.

Understanding the intersection of race and gender as it relates to public opinion toward Michelle Obama is especially important given her role as the nation's first African American first lady. During the 2008 campaign, Michelle Obama often faced harsh criticism that drew on negative stereotypes associated with black women, including dominance, anger, and a lack of femininity. These narratives were especially harmful because they run counter to themes of warmth, beauty, motherhood, and other symbols representing “feminine respectability.”Footnote 5As Block and Haynes (Reference Block, Haynes, Mitchell and Covin2017) aptly note, these symbols—and how African American women are judged by them—play and important role in shaping the ability of African American women to organize politically and to promote legislative agendas. In the case of Michelle Obama, these symbols were likely especially potent, as the symbols of feminine respectability to a large degree dovetail with the characteristics associated with “traditional” first ladies, and those who deviate from these characteristics often face public backlash (Burrell, Elder, and Frederick Reference Burrell, Elder and Frederick2011). The incongruence between narratives surrounding Obama and views of a traditional view of the first lady created a uniquely raced-gendered terrain for her first ladyship.

Upon entering the office of the first lady, Obama embraced the symbols of traditional first ladies, choosing to emphasize her status as a wife and mother (Duerst-Lahti Reference Duerst-Lahti, Carroll and Fox2014; Elder and Frederick Reference Elder and Frederick2017). The issues she chose to emphasize, related to children's health and education, reinforced traditional views of the first ladyship and softened her image considerably among the public. Yet Obama still faced a uniquely raced-gendered terrain during her time as first lady. As Block and Haynes (Reference Block, Haynes, Mitchell and Covin2017, 99) note, Michelle Obama “has the unenviable task of advocating for … minority group inclusion while simultaneously modeling White, middle to upper-class, heterosexist, and patriarchic [symbols].” In other words, as a woman of color (and as the first presidential candidate spouse of color), Michelle Obama was forced to navigate the gendered terrain inherent in the first ladyship in an inherently racialized way.

Thus, Michelle Obama's race and gender were inextricably linked and jointly influenced her experiences on the campaign trail and as first lady, and they jointly shaped public response to her. This is not unique to Obama. Indeed, research on minority women contends that race and gender are inextricably linked: an individual's racial experience is shaped by their gender and vice versa (Gay and Tate Reference Gay and Tate1998; Mansbridge and Tate Reference Mansbridge and Tate1992). In this sense, to understand public opinion toward Michelle Obama, we must consider her race through the prism of gender and, likewise, consider her gender through the prism of race. Further, we must consider how race and gender intersected for members of the public and how these intersections influenced public reaction to Michelle Obama. Accounting for this intersectionality allows us to create a more accurate and nuanced picture of public opinion toward the first lady.

As a concept, intersectionality allows scholars to understand and explore the ways that race and gender interact to shape the political experiences of minority women (see Brown Reference Brown2014b; Junn and Brown Reference Junn, Brown, Wolbrecht, Beckwith and Baldez2008). As Crenshaw (Reference Crenshaw1989, Reference Crenshaw1991) conceived the concept, intersectionality refers to overlapping systems of oppression and the consequences these systems have for black women. Other scholars have referred to what is called the “double bind,” or the notion that women of color are disadvantaged within their racial or ethnic group on the basis of gender and are likewise disadvantaged in their gender group because of their race or ethnicity (Brown Reference Brown2014b; Cassese, Barnes, and Branton Reference Cassese, Barnes and Branton2015; Githens and Prestage Reference Githens and Prestage1977; King Reference King1988). Though some scholars note the general lack of intersectionality in mainstream political science (Alexander-Floyd Reference Alexander-Floyd, Mitchell and Covin2017), research on minority women has certainly increased over the last decade.Footnote 6 As Smooth (Reference Smooth2016, 513) notes, intersectionality “forces scholars to engage complexity by recognizing the differences that exist within groups—a recognition that moves beyond simply the differences between groups.” Applied to public opinion, this research points to the potential for heterogeneity in public opinion toward Michelle Obama, with African American women differing from African American men and from white women.

The broader literature on minority women does indeed suggest that race and gender fuse to create unique experiences for women of color. As legislators, Orey et al. (Reference Orey, Smooth, Adams and Harris-Clark2007) find, African American women are distinct in their promotion of progressive policies. Brown (Reference Brown2014a) finds that black women legislators interpret their own experiences through an intersectional lens, discussing their priorities and experiences in distinctly raced-gendered ways. In electoral politics, research suggests that while overall levels of women's representation in state politics have stagnated, African American women have continued to make gains (Smooth Reference Smooth2006). At the mass level, numerous scholars have documented important differences in women's participation patterns based on race and have noted that traditional factors thought to influence women's participation do not equally apply to all women (Holman Reference Holman, Brown and Gershon2016; Junn Reference Junn1997; Smooth Reference Smooth2006). In terms of public opinion, gender has been shown to meaningfully influence black attitudes toward sexual harassment and other issues related to women (Gay and Tate Reference Gay and Tate1998; Mansbridge and Tate Reference Mansbridge and Tate1992).

The distinctiveness of the minority woman experience has led some scholars to argue that women of color have developed their own group identity. The intersection of race and gender creates an identity that is distinct and more than the sum of an individual's race or gender (Philpot and Walton Reference Philpot and Walton2007). This group identity should lead African American women to be especially supportive of political figures who share their status as minority women. Indeed, Philpot and Walton (Reference Philpot and Walton2007) find evidence that this is the case in their analysis of support for black female candidates. In their analysis, the authors find that black women were the most likely to support candidates when those candidates shared both their race and their gender. Stokes-Brown and Dolan (Reference Stokes-Brown and Dolan2010) likewise find that African American women candidates mobilize African American women in the electorate, making them more likely to vote and to participate in proselytizing activities. Together, these studies suggest that as public officials, African American women may hold special meaning for African American women in the general public. We would expect that similar findings in the context of nonelected officials and that African American women would be more supportive of Michelle Obama than both African American men and white women.

While both women and African Americans remain underrepresented in politics, women of color are especially disadvantaged, holding just 7% of seats in Congress and 6% of seats in state legislatures (CAWP 2018). Thus, the presence of a high-profile African American woman in politics, as Michelle Obama was, should be especially likely to elicit a positive response from black women. Because of their uniquely disadvantaged status in American politics, black women may be especially likely to respond favorably to Michelle Obama and to view her as a salient political symbol. Indeed, Michelle Obama was consistently the most highly visible African American woman in American politics during her time in the White House, perhaps making her especially likely to be a politically relevant figure for other African American women. Yet to date, research on how race and gender jointly influenced public opinion toward Michelle Obama is limited. We view this as an unfortunate omission in the literature on first ladies and candidate spouses. As one of few nationally prominent women of color in American politics, Michelle Obama presents an especially salient case in which to examine how race and gender jointly shape public opinion toward political figures.

While we expect African American women to be Michelle Obama's strongest base of support, we expect that she still enjoyed higher levels of support from African American men (relative to white men) and white women (relative to white men). In the sections that follow, we examine public opinion toward Michelle Obama and how opinion differed across four groups: black women, black men, white women, and white men. In doing so, we offer a nuanced analysis of how Obama's race, gender, and the intersection of her race and gender influenced the formation of public opinion toward the first lady. Further, we use a wide array of indicators rather than relying simply on the favorability ratings frequently used in prior studies of public opinion toward the first lady.

TRENDS IN MICHELLE OBAMA'S FAVORABILITY: 2008–17

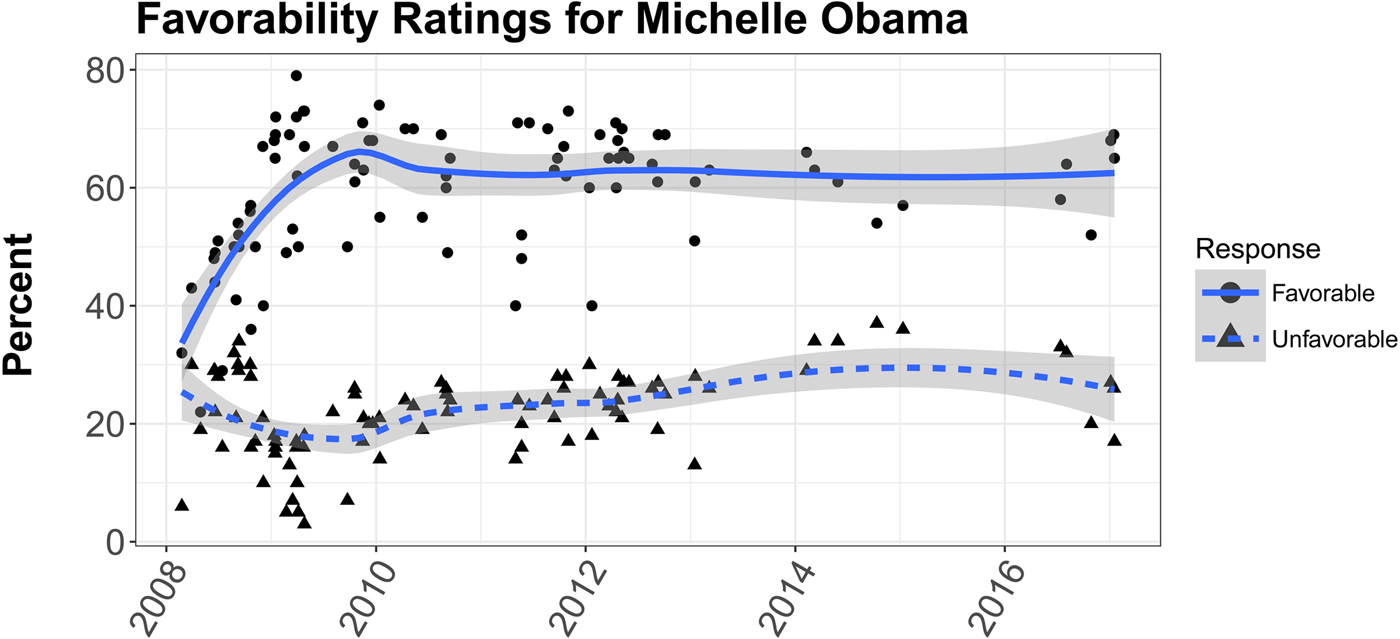

We begin our analysis by examining trends in Michelle Obama's favorability and unfavorability ratings between 2008 to 2017. To find relevant polls, we searched the archives of the Roper Center for Public Opinion Research for polls on Michelle Obama. To maintain comparability across polls, we only include polls that asked about favorability and excluded those with different question wording, such as those asking about support or confidence.Footnote 7 Further, to ensure consistency in response options, we only include polls that either (1) used binary favorable or unfavorable indicators or (2) initially used a binary favorable or unfavorable indicator and then branched into multiple response options (e.g., strongly, somewhat strongly, weakly). For questions that included branching options, we collapse responses to either favorable or unfavorable.Footnote 8 This approach left us with a total of 91 polls between 2008 and 2017.

The 91 polls we collected are plotted in Figure 1. The circles represent Michelle Obama's favorability ratings, while the triangles represent her unfavorability ratings, with the solid and dashed lines representing a loess trend for each series, respectively. Michelle Obama's favorability was initially somewhat low, averaging 45% in 2008. We find that this is not due to the fact that Michelle Obama was unpopular (during this time, Michelle Obama's average unfavorability rating was just 25%) but to many people responding “don't know” when asked. This makes sense, as during this time frame, Michelle Obama was just being introduced to the public. As the public became more aware of Michelle Obama, those who responded “don't know” decreased, favorability increased, and unfavorability ratings stabilized. Through the entire series, Michelle Obama had an average favorability of 59.65% and an average unfavorability of 22%. At no point did more individuals view Michelle Obama unfavorably than favorably, and Michelle Obama maintained a high net favorability, which averaged 37.6%.

Figure 1. Favorable and Unfavorable Ratings of Michelle Obama 2008–2017.

These trends are consistent with previous research examining public opinion toward first ladies and would-be first ladies. Burrell, Elder, and Frederick (Reference Burrell, Elder and Frederick2011) find that spouses of presidential hopefuls generally enjoy much higher levels of favorable than unfavorable attitudes. Other studies have similarly noted that first ladies tend to be liked by larger portions of the public than those expressing dislike (Burrell Reference Burrell2001; Burrell, Elder, and Frederick Reference Burrell, Elder and Frederick2011; Cohen Reference Cohen2000; Sulfaro Reference Sulfaro2007). Further, the sharp increase in favorability between 2008 and 2010 supports Burrell, Elder, and Frederick's assertion that the more the public comes to know presidential spouses, the more they tend to like them. Finally, the relative stability of Michelle Obama's favorability post 2010 supports the notion that the first lady is relatively insulated from political developments that engulf presidential administrations.

In short, in terms of general favorability trends, opinion toward Michelle Obama seems to follow patterns that are consistent with the literature on first ladies. After an initial period of becoming more familiar with Michelle Obama, the American public seems to have embraced her, allowing Michelle Obama to enjoy consistently high favorability ratings. Further, this consistency underscores that Michelle Obama was somewhat insulated from political tumultuous developments and that her favorability ratings were able to stay above the fray of partisan politics.

THE BLACK WOMEN IN AMERICA SURVEY

To further examine how the public viewed Michelle Obama, we use survey data from the Black Women in America survey, which was conducted by the Washington Post and Kaiser Family Foundation in October and November 2011. As Cohen (Reference Cohen and Carroll2003) notes, studying the intersection of race and gender using survey data can be challenging because nationally representative polls often do not include a large enough subsample of African American women to make meaningful inferences. The survey we employ in our analysis was conducted by telephone using random-digit dialing and included an oversampling of African American respondents. This oversampling of African Americans provides us with a significant advantage and gives us with the leverage necessary to test how the intersection of racial and gender identities influenced perceptions of Michelle Obama. The survey included 1,936 respondents. In addition to including a large number of African American respondents, the survey also included a number of novel survey items that allow us to test public response to Michelle Obama beyond the typical favorability/approval rating found in most studies of public opinion and first ladies.

We analyze how the public viewed Michelle Obama on three dimensions: (1) general favorability, (2) attention to her policy initiatives, and (3) how her presence influenced attitudes toward African American women more generally. To measure favorability, we use a question that asked respondents whether they had a favorable or unfavorable impression of Michelle Obama and included a follow-up about whether their favorable or unfavorable impression was strongly held or not. In all, 63.7% had strongly held favorable views, 23.2% had somewhat favorable views, 7.7% had unfavorable views, and 5.4% had strongly held unfavorable views toward Michelle Obama.

To measure attention to Michelle Obama's policy initiatives, we use a question that asked respondents how much they have heard about her Let's Move campaign against childhood obesity. The Let's Move campaign, which was launched in February 2010, was one of Michelle Obama's signature policy initiatives. The goal of Let's Move was to reduce childhood obesity by encouraging physical activity and healthy eating habits. The response set included three categories: “a lot,” “a little,” and “nothing at all.” Among the respondents, 43.3% had heard a lot, 41% had heard a little, and 16% had heard nothing at all about Let's Move.

To capture how Michelle Obama's status as the first African American first lady influenced respondents’ perceptions of African America women, we use a question that asked respondents whether having Michelle Obama as the country's first African American first lady changed their overall impression of black women in America. Respondents could reply yes or no and then were asked a follow-up to determine whether their change in impression was better or worse. In total, 30% replied that Michelle Obama changed their perception of black women in American, and of those, 95% said the change was for the better. Because there is little variation in the direction in which Michelle Obama changed respondents’ perceptions of black women in America, we collapse the responses into a binary that is coded 1 if the respondent reported a positive change in impression and 0 otherwise.

RESULTS

Two binary variables are used to capture survey respondents’ race. African American takes the value 1 if the respondent identified as African American and 0 otherwise. Latino takes the value 1 if the respondent identified as Latino and 0 otherwise. This leaves white respondents as the excluded baseline. The female variable takes the value 1 if the respondent identified as a female and 0 otherwise. Since we are interested in how perceptions of Michelle Obama varied at the intersection of race and gender, we include an interaction between the African American and female variables. Beyond these characteristics, we control for respondents’ age, education, ideology, partisanship, and whether they voted for President Obama in the 2008 election.

Because the response sets for favorability and attention to Let's Move are ordered categorical variables, we estimated two ordered logistic regression models to examine which factors best explain these concepts. Since the improves perception of black women variable is binary, we estimate a logistic regression model to explain these attitudes. The results of our three models are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Regression Models: Attitudes toward Michelle Obama

Models 1 and 2 are ordered logistic regressions, model 3 is a binary logistic regression

Standard errors in parentheses

* p <0.05, ** p <0.01, *** p <0.001

The first column of Table 1 presents the results of the ordered logistic regression, which estimate a respondent's favorability toward Michelle Obama. Because we are interested in determining the effect of descriptive identities and the intersections of those identities with favorability toward Michelle Obama, we are mainly interested in interpreting the coefficients for the African American and female variables as well as the interaction term. To facilitate the interpretation of the model, we present the predicted probabilities of each group selecting each response option in Figure 2. The results demonstrate that African Americans were more likely to view Michelle Obama as strongly favorable than white respondents. Specifically, the probability that an African American would strongly favor Michelle Obama was .74, while the probability of a white respondent being in the strongly favor response category was .56. We also observe that African Americans were significantly less likely to view Michelle Obama unfavorably or strongly unfavorably (p < .05 in all instances). We observe no gender differences among whites or African Americans.

Figure 2. Results to Model 1 in Table 1. Points represent best estimate and bands represent 67% intervals to show statistically significant differences at p < .05.

This contrasts with previous studies, which have found that women are more likely to support the first lady than men and that women were more likely to support Michelle Obama in particular (Burrell, Elder, and Frederick Reference Burrell, Elder and Frederick2011; Elder and Frederick Reference Elder and Frederick2017; Knuckey and Kim Reference Knuckey and Kim2016). Our findings on race, however, are consistent with previous research on public opinion toward Michelle Obama (Elder and Frederick Reference Elder and Frederick2017). A potential implication of our findings is that gendered effects on public opinion toward Michelle Obama may have faded outside an electoral context, while racial effects may have been more enduring over the course of the administration.

The second model in Table 3 presents the results of the ordered logistic regression predicting how much information respondents reported having about Michelle Obama's Let's Move campaign. Figure 3 presents the predicted probabilities of each identity group selecting each response option. The results indicate that race was a strong predictor of attentiveness to the Let's Move campaign. The probability of an African American respondent having “a lot” of information about the campaign was .48, compared with a probability of .39 for white respondents. Further, whites had a significantly higher probability—.152—of reporting hearing nothing about Let's Move, as opposed to .112 for African American respondents.

Figure 3. Results to Model 2 in Table 1. Points represent best estimate and bands represent 67% intervals to show statistically significant differences at p < .05.

Unlike evaluations of favorability, we do observe some gender differences in attentiveness to the Let's Move campaign. The probability of a white women reporting that she had heard “a lot” about Let's Move was .418, compared to .352 for a white man. Further, the predicted probability that a white man had heard nothing about Let's Move—.178—was significantly higher than that of a white woman—.140—not having heard anything about Let's Move (p < .05 in all instances). However, we observe no differences in the attentiveness to Let's Move between African American women and men. These findings suggest that, as with favorability, race is the dominant determinant of awareness for Michelle Obama's policy agenda. However, unlike our results for favorability, the results of this model indicate there is room for gender to play a role in policy awareness. Thus, while white women may not have liked Michelle Obama better than white men, they were nonetheless more attentive to her policy actions and more likely to be aware of developments related to her activities as first lady.

The third column in Table 1 presents the results of the logistic regression predicting whether Michelle Obama improved the respondent's perception of black women. The results are presented as predicted probabilities for each group in Figure 4. Here, our results are not best explained by race but are more nuanced and align with theories of intersectionality. African American women were significantly more likely to update their attitudes about African American women because of Michelle Obama's presence as first lady than white men or women (p < .05). African American women had a predicted probability of .32 of replying that Michelle Obama improved their perception of black women, while white men and white women had predicted probabilities of .219 and .198, respectively. However, African American men were no more likely than white men and women to view African American women more favorably because of Michelle Obama's presence as first lady. In other words, Michelle Obama's tenure as first lady uniquely impacted African American women's assessments of their own race-gender group. This suggests that Michelle Obama served as a unique role model for other African American women and that her prominence served as a rallying point for the group to increase feelings of pride and group affect. This suggests not only that race and gender influenced public opinion toward Michelle Obama but also that her presence influenced how African American women viewed themselves collectively. Thus, it appears that in the context of African American women, Michelle Obama served as an important representative figure for African American women and that her presence was a uniquely empowering force for this group.

Figure 4. Results to Model 3 in Table 1. Points represent best estimate and bands represent 67% intervals to show statistically significant differences at p < .05.

Finally, we note that across each of our three models, political factors, such as partisanship, vote choice, and in some cases ideology, all predict attitudes toward Michelle Obama. Specifically, Democrats, liberals, and those who voted for her husband viewed Michelle Obama as more favorable, had heard more about her Let's Move initiative, and believed she improved the perception of black women in American when compared with Republicans, conservatives, and those who voted for other candidates in 2008. These findings are consistent with previous research on how partisanship influences public opinion formation toward first ladies (Burrell Reference Burrell2001; Burrell, Elder, and Frederick Reference Burrell, Elder and Frederick2011; Knuckey and Kim Reference Knuckey and Kim2016; Mughan and Burden Reference Mughan, Burden and Weisberg1995; Sulfaro Reference Sulfaro2001; Tien and Miller Reference Tien, Checchia, Miller and Whitaker1999).

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

Public opinion toward the first lady remains an underdeveloped subject in the political science literature. While scholars have begun to focus some attention on the relationship between the public and the first lady, more research is needed to fully evaluate the political implications of presidential spouses. The present study contributes to this literature while also helping broaden our understanding of how various subgroups in the American public respond to black women who serve in prominent political roles. As one of few high-profile African American women in American politics, Michelle Obama represents a compelling case to examine the extent to which the intersection of race and gender meaningfully contributes to public opinion toward political actors. Though not an elected official, Michelle Obama was a prominent figure in the Obama administration, and the language of symbolic politics was often evoked in discussions of her legacy as first lady. While previous studies have accounted for race and gender in understanding evaluations of Michelle Obama, our research examines how the intersection of these descriptive identities influenced public opinion toward Michelle Obama.

Our analysis suggests that, like other first ladies, Obama enjoyed a generally positive relationship with the American public. An examination of public opinion polls from 2008 to 2017 reveals that more Americans viewed Michelle Obama favorably than unfavorably, and that over the course of her time in the White House, there was never a time when Michelle Obama did not enjoy a net favorable evaluation from the American public. Indeed, Michelle Obama's overall favorability was relatively stable across the time period, with the exception of 2008–10, when public opinion steadily increased before ultimately stabilizing. This suggests that much of Michelle Obama's favorability had more to do with who she was, rather than political developments within the administration. If Michelle Obama's favorability was tied to political events and developments, we would expect to see noticeable shifts across the series, rather than the stable trends we observe.

Using the Black Women in America study, we were able to further examine public opinion toward Michelle Obama and to expand our analysis beyond favorability ratings. This expansion allowed us to more fully examine how the public reacted to Michelle Obama and the extent to which she was able to provide symbolic representation to women, African Americans, and African American women. Like previous studies, we found that there was a significant racial component to opinion toward Michelle Obama. African Americans were significantly more favorable toward Michelle Obama than whites and more likely to report having information on the Let's Move campaign. Unlike previous studies, we do not observe differences in favorability rooted in the respondent's gender. However, we did observe that white women were more likely to report having information about Let's Move than white men. This suggests that while gender did not necessarily play a role in how women evaluated Michelle Obama personally, it did play a role in the extent to which women were aware of her policy activities.

Finally, our results on perceptions of black women suggest that the intersection of Michelle Obama's race and gender uniquely positioned her to serve as an empowering symbol for other black women in the United States. When asked whether Michelle Obama had increased perceptions of black women collectively, the group most likely to agree were black women themselves. This suggests that Michelle Obama's performance in her role as first lady increased feelings of group pride among African American women, and that their own perceptions of self were enhanced by seeing someone like them on the national political stage. These improvements in group affect could have downstream benefits for African American women and lead to higher levels of political efficacy, participation, and political ambition. Though further research is needed to assess the relationship between Michelle Obama's first ladyship and these outcomes, we view these areas as promising extensions of the research presented here. Further, we note that while we are unable to speak to these questions directly in the present study, we feel that our finding regarding Michelle Obama and African American women's group perceptions is important in its own right and speaks to the potential power of first ladies to provide representation to various constituencies.

The analysis presented in this article has implications for the literatures on the first ladies; public opinion; and gender, race, and ethnicity politics. First, our findings underscore that future analyses of the first ladies must take into account Michelle Obama's unique status as an African American woman in order to fully understand who supported the first lady and why. Second, our findings highlight that to fully understand how the public reacts to the first lady, scholars should use a wider array of indicators than the favorability ratings typically used. Finally, our study represents an important new contribution to our understanding of public reactions to African American women in politics. Studies on affect toward minority women in politics have been relatively limited (see Philpot and Walton Reference Philpot and Walton2007; Stokes-Brown and Dolan Reference Stokes-Brown and Dolan2010 for notable exceptions). This is largely due to the dearth of prominent African American women in American politics, making it difficult to study how the public reacts to such figures. Though nonelected, Michelle Obama was a highly visible figure in American politics over the course of her husband's administration, and understanding her role as a political symbol helps us better understand how descriptive representation influences feelings of symbolic representation among minority women.