Government policy frameworks for gender equality are critical in the sense that they affect all domestic laws, regulations, and practices. These frameworks, called “Blueprint policies” by Mazur (Reference Mazur2002), refer to the general formal frameworks that establish principles of gender equality and promote women's rights in government actions (Mazur Reference Mazur2002). These policies include a range of constitutional provisions, legislation, action plans, reports, and policy machinery that governments use to establish general feminist principles for action at the national and subnational levels (Mazur Reference Mazur2002).

A number of actors and factors can help drive successful government action to adopt better policy frameworks for gender equality. A closer look at these might shed some light on the adoption of gender equality policies (Mazur Reference Mazur2002). Espousing Mazur's argument that the “determinants of feminist policy formation are highly complex” (Reference Mazur2002, 175), this study aims to discover whether regional international parliaments play an important role in the development of more gender-equal policy frameworks by controlling for a variety of factors. Accordingly, the primary research question is: What is the impact of regional international parliaments on the adoption of government policy frameworks for gender equality?

The internationalization of gender norms is an important factor that pressures national governments to adopt better policy frameworks for gender equality. The United Nations (UN) has played a particular role in the development of a global framework for gender equality, especially since the adoption of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) in 1979. Besides a global gender regime driven by UN agencies, one can also assume that there are other gender regimes around the world. Bose (Reference Bose2015) demonstrates that there are three different gender regimes across the regions, challenging generalizations about the global South and global North. In East Asia and the Pacific and South Asia, political-economic structures and gendered institutions have no significant impact on inequality, whereas political-economic variables play a significant role in Europe, Latin America, and the Middle East and North Africa (Bose Reference Bose2015). One of the best-known examples of such pressure is the European Union (EU). The EU has a particular interest in and a distinctive power to push its members to adopt better gender equality policies. Gender inequality in sub-Saharan Africa, as a third pattern, is affected by both gendered institutions and political-economic inputs (Bose Reference Bose2015).

Supporting the arguments regarding the existence of multiple gender regimes, one might question the role that regional international parliaments play in the construction of policy frameworks for gender equality. Regional international parliaments around the world are continuously developing mechanisms and structures to achieve gender sensitivity among their member states. Regional international parliaments at both the national and international levels play an innovative role in supporting the interests of minorities, including women (Celis and Woodward Reference Celis, Woodward and Magone2003). They continue to develop regional gender regimes and tools for gender mainstreaming in all operational infrastructures and institutional cultures as a means to ensure gender equality between men and women (IPU 2016). These efforts might focus on different areas, such as equal representation and recruitment, stronger policy frameworks including legal documents and their implications, or the creation of gender-sensitive political infrastructure and culture in both parliaments and political parties (IPU 2016). Although regional international parliaments have the potential to develop such mechanisms, it is also known that not all regional international parliaments have such aims or, if they have the power, the intention and the political will to do so.

This article aims to analyze the impact of regional international parliaments on government policy frameworks for gender equality, asking whether being a member of a regional international parliament significantly increases the degree to which a national gender equality policy framework has been developed in a country. The article is organized into four sections: The first section focuses on the theoretical background on the effect of regional international parliaments on gender equality policies. The second section presents the operationalization of variables and methodological explanations. The third section maps the components of government policy frameworks for gender equality. The fourth section present the results of the analyses and the findings of this research.

THE ASSOCIATION BETWEEN REGIONAL INTERNATIONAL PARLIAMENTS AND NATIONAL GENDER EQUALITY POLICY FRAMEWORKS

In a rapidly globalizing world, the effect of international actors on gender equality policies cannot be disregarded. International legal mechanisms can push for gender equality by encouraging and even requiring nation-states to actively promote gender equality (Sweeney Reference Sweeney2004, Reference Sweeney, Hertel and Minkler2007). The UN is one of the most important international actors pushing national governments to take action on issues such as violence against women and gender equality. CEDAW was an important step by the UN General Assembly, as it recognized discrimination against women and established an agenda for national action to fight such discrimination as a means to achieve gender equality. The Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action, adopted by 189 countries, is also considered a turning point in the global agenda for gender equality in the sense that it is a global political agreement. However, the UN system has proven to be largely ineffective at ensuring that governments comply with its gender equality policies (Kardam Reference Kardam2002).

As a result, besides the UN's global efforts, regional efforts and mechanisms have become important tools for ending discrimination against women and fostering gender equality. Such successful governing mechanisms were also developed by regional international forums such as Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC). APEC has developed and implemented gender mainstreaming in organizational processes and operational outputs by implementing a gender-integration framework (True Reference True, Rai and Waylen2008).

Another notable example of the establishment of regional gender equality mechanisms was developed by the EU. Since the 1970s, the EU has been widely regarded as one of the most important nonstate actors in the creation of gender equality policies (Macrae Reference Macrae2006; Walby Reference Walby2004). The European Parliament, a key institutional body of the EU, functions as the core actor and the main gender equality policy machinery through the Network of Members on Gender Mainstreaming (Ahrens Reference Ahrens2016). The Council of Europe, another international parliament, is a pioneer in initiating gender equality policies under its constituency and combats violence against women through the Istanbul Convention (Verloo Reference Verloo2005).

According to Walby (Reference Walby2004), the EU has two key powers related to gender equality that are applied to national governments. First, the EU has the power to regulate the economies of national governments, although its effect on gender relations remains limited because decisions are made mostly at the local level (Walby Reference Walby2004). The second power that the EU holds over member states relates to the processes of convergence and homogenization, which can be explained by two arguments. One is that the homogenization of political and social structures hinders justice and equity policies because of the decreased power of individual nation-states as a result of globalization; the other is that there is a diffusion of gender equality norms among emerging-world polities (Walby Reference Walby2004). The European Parliament has been shown to have considerably greater powers than regional international parliaments (Cofelice and Stravridis Reference Cofelice and Stavridis2014).

Cofelice and Stravridis (Reference Cofelice and Stavridis2014) identify 23 regional international parliaments, which are also referred to as interparliamentary institutions, interparliamentary organs, or interparliamentary associations.Footnote 1 Thus, I can say that the world governance system includes such parliamentary networks in which national governments participate. The impact of these regional international parliaments on national governments differs across regions, as they might be considered by some countries attempts to transfer the parliamentary control of governments to another institution at the international level (Finizio, Levi, and Vallinoto Reference Finizio, Levi and Vallinoto2011).

Even though international laws and regulations can have an important impact on countries’ gender equality policies, the implementation of those international regulations at the national level is often uncertain. Often, a lack of forceful sanctions and the weakness of enforcement mechanisms result in a low level of compliance with international organization's gender equality requirements (Landman Reference Landman2005; Sweeney Reference Sweeney2004, Reference Sweeney, Hertel and Minkler2007; Wangari, Kamau, and Kinyau Reference Wangari, Kamau and Kinyau2005). Therefore, the strength of the international institutions and their enforcement mechanisms often play a crucial role in the implementation of international gender norms. Cofelice and Stravridis (Reference Cofelice and Stavridis2014), in comparing regional interparliamentary institutions, demonstrate that every regional international parliament has different levels of power of enforcement. For example, the European Parliament has a unique impact on national governments because of its power of consultancy, oversight, budgeting, and legislation (Cofelice and Stravridis Reference Cofelice and Stavridis2014). On the other hand, regional international parliaments such as the Benelux Interparliamentary Consultative Council, the European Free Trade Association's Parliamentary Committee, or the Consultative Council of the Arab Maghreb Union only have some degree of consultative power.

Although regional international parliaments’ effect on democracy is widely discussed in the literature (e.g., Cofelice and Stravridis Reference Cofelice and Stavridis2014; Sabic Reference Sabic2008; Slaughter Reference Slaughter2004), few studies focus on their impact on the gender equality policy frameworks of national governments. The literature largely confines itself to EU institutions (e.g., Celis and Woodward Reference Celis, Woodward and Magone2003; Kantola Reference Kantola2010; Pascall and Lewis Reference Pascall and Lewis2004; Pollack and Hafner-Burton Reference Pollack and Hafner-Burton2000; Walby Reference Walby2004), leaving the effects of other regional international parliaments unexplored. Therefore, this study contributes to the literature by focusing on the impact not only of the EU but also of other regional international parliaments. In doing so, it questions whether a stronger regional international parliament correlates with better government policy frameworks for gender equality. This leads to another query concerning the extent to which regional international parliaments contribute to gender equality in their member nations.

Regional international parliaments may adopt diverse measurements, mechanisms, and tools to strengthen gender equality. First, regional international parliaments may pioneer the creation of women's policy agencies to promote gender equality and gender mainstreaming. These agencies may be responsible for different duties such as management, implementation, or research. For example, the Gender Equality Commission of the Council of Europe is also a women's policy agency and has a comprehensive mission to ensure gender mainstreaming in all policies and to ensure that international-level commitments have been implemented in Europe (Council of Europe 2019). The European Institute for Gender Equality is a research agency affiliated with both the Council of Europe and the European Parliament.

Second, regional international parliaments and women's policy agencies may adopt policy documents and legislation that pressure governments to take up gender equality policies at the national level. The Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) adopted a gender policy to achieve the goal of gender equality in 2004 that was improved by a Supplementary Act in 2015 (ECOWAS 2015; EGDC 2019). Another striking example is the ratification of the Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights on the Rights of Women in Africa in 2005, also known as the Maputo Protocol. The Maputo Protocol is a product of the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights of the African Union and consists of many articles to prevent violence against women and discrimination against women and to promote gender equality (African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights 2003).

Third, regional institutions may promote the development of regional strategic plans, action plans, and agendas, as well as the settlement of development goals. For example, the Southern Common Market (MERCOSUR) Parliament set a regional gender agenda, and the Parliamentary Women's Bloc prepared a detailed Institutional Strategic Plan for the years 2013–17, aiming to promote gender equality both in institutional designs and through the actions of the Central American Parliament (PARLACEN) (Parliamentary Women's Bloc 2013). Another noteworthy example is the Council of Europe's Gender Equality Strategy (covering the periods 2014–20 and 2018–23), which has been a constant and dynamic process committed to achieving gender equality within member states and the organization. Another way of setting an agenda is to outline gender equality provisions in the development goals of regional institutions, such as the Millennium Development Goals 1990–2013 of the Central African Economic and Monetary Community (CEMAC), which include an item to promote gender equality and empower women.

Fourth, regional international parliaments may organize forums and meetings to discuss gender equality and the empowerment of women. One noteworthy example is the Eurasian Women's Forum organized by the Interparliamentary Assembly of Member Nations of the Commonwealth of Independent States. The First Forum was held in 2015 and included approximately 1,000 participants from 80 countries. The Second Forum was held in 2018 with around 2,000 participants from 110 countries, also attended by representatives of international organizations such as the UN, the World Health Organization, and the International Labour Organization (Eurasian Women's Forum 2018). Both forums were particularly productive in terms of their outcomes, since after each forum, an Outcome Resolution was released. In addition, a Joint Declaration on Trade and Women's Economic Empowerment was published after the World Trade Organization's Ministerial Conference in Buenos Aires in December 2017 (Eurasian Women's Forum 2018). The Pan-African Parliament (PAP) also organizes Annual Women's Conferences to discuss different issues such as female genital mutilation, corruption, or reproductive health, all of which are crucial problems in Africa. The Annual Conferences are established not only as a forum to discuss women's issues but also as a control mechanism that tracks the process and monitors the implementation of PAP's gender equality and women's empowerment policies (Nassir Reference Nassir, Matlosa, Musabayana, Abdulmelik and Nyoyo2016).

Fifth, regional international parliaments and the women's policy agencies within them may produce data and initiate reports and research projects. The best example of such data production is Eurostat, which provides a wide range of statistical data. Providing data and information on gender equality indicators is an important way to raise awareness of the issue of gender inequality and develop some solutions. Therefore, the research activities of regional parliamentary institutions possess a great deal of power in policy-making processes. An example of such a project is the Nordic Gender Effect at Work, supported by the Scandinavian prime ministers, which aims to promote gender equality as a precondition for decent work and economic growth (Nordic Cooperation 2019).Footnote 2 In addition, CEMAC launched a Gender Project in June 2016, aiming to develop a strategy for the promotion of gender equality. This project analyzes various approaches to gender equality, comparing structural differences among countries and subregions of the community to develop the best gender policy for the community (CEMAC 2012, 34).

Lastly, regional international parliaments and women's policy agencies might offer some training programs for different target groups. For instance, the Parliamentary Women's Bloc (2019) in PARLACEN provided several training sessions on gender equality issues to deputies and technical and administrative staff of the Central American Parliament Headquarters. These forms of training are crucial in that they educate officials and policy makers in regional institutions on how to tackle gender inequality and raise awareness of the issue at the same time. Thus, it can be argued that training of this kind can foster institutional-level understanding of gender equality and gender mainstreaming in regional international parliaments.

The wide range of institutions and activities presented here demonstrates that international regional international parliaments may pressure national governments to the degree that they become more proactive on gender equality issues. Thus, this article aims to examine the linkage between regional international parliaments and government policy frameworks for gender equality.

METHOD AND OPERATIONALIZATION OF VARIABLES

Dependent Variable: Government Policy Framework for Gender Equality

In this study, the government policy framework for gender equality is considered to be a multidimensional phenomenon.Footnote 3 For the aim of this study, the Blueprint Scale (scaled for 2010) created by Ertan (Reference Ertan2016) was revised and updated in 2016, and the country coverage was expanded from 84 to 176 countries with populations greater than 200,000 by 2015. However, because of a high degree of missing data in the control variables, Palestine was dropped from the statistical analyses.

The scale is designed to be multidimensional, using three indicators that identify the degree to which a general policy framework for feminist government action exists within a country: (1) a legal declaration of gender equality; (2) the existence of a gender equality action plan; and (3) a commitment to the international gender equality regulation (CEDAW). These three indicators aim to capture the legislative, practical, and international dimensions of the gender equality policy framework of a country. These three subscales together produce a composite scale ranging from 0 (weak policies) to 7 (strong policies).

First Dimension: Legal Declaration of Gender Equality

This subscale seeks to determine whether and the degree to which the state has codified gender equality in law, either in its constitution or through legislation. This subscale is coded as follows:

2 = The country has a clause on gender equality and nondiscrimination in its constitution, or it has specific gender equality and nondiscrimination legislation (such as a gender equality law or sex discrimination act) and customary law is not considered valid if it contradicts or violates that clause.

1 = The country does not have either a gender equality clause or a nondiscrimination clause in the constitution. It does not have specific gender equality legislation, but it may have nondiscrimination legislation. Even so, customary law is not considered valid when it contradicts or violates gender equality and/or the nondiscrimination principle.

0 = The country does not have either a gender equality clause in the constitution or gender equality legislation, and it does not have a nondiscrimination clause or legislation. However, a country is coded 0 when it has gender equality or nondiscrimination clauses or legislation but customary law is considered valid even if it contradicts or violates these.

Second Dimension: Gender Equality Action Plan

This subscale determines whether the country has a comprehensive and current national gender equality action plan. This subscale is coded as follows:

2 = The country has a comprehensive and current national gender equality action plan that tackles the gender issue as a multidimensional phenomenon, such as a gender equality action plan, gender action plan, or women's empowerment action plan.

1 = The country has a national program, but it is not comprehensive or it has lapsed (e.g., equal employment action plan, national action plans on women peace and security, or national action plan on domestic violence).

0 = The country has no national action plan for gender equality and its other, more limited gender equality programs, if they exist, are very weak.

Third Dimension: Commitment to the International Gender Equality Framework

This subscale ranks the degree to which the nation has committed itself to CEDAW:

3 = Ratified, no reservation, signed Optional Protocol

2 = Ratified, no reservations, did not sign Optional Protocol

1 = Ratified, but with reservations

0 = Did not ratify

Added together, these three subscales establish a composite measurement ranging from 0 (weak policies) to 7 (strong policies).

Explanatory Variable: Strength of Membership in Regional International Parliaments

Cofelice and Stravridis (Reference Cofelice and Stavridis2014) developed a scale measuring the strength of legislative powers, budgetary powers, appointment powers, oversight powers, and consultative powers in 23 international parliaments. This study uses Cofelice and Stravridis's data and measures the strength of the international parliaments to which each country belongs. A combination of the various types of powers that international parliaments possess demonstrates the degree of actual involvement that international parliaments have in a government's policy production. This Index of Parliamentary Powers measures the strength of each type of power—legislative, budgetary, appointment, oversight, and consultative powers—on a scale from 0 to 5. For instance, a moderate level of power corresponds to a score of 2, whereas no power corresponds to a score of 0. (For more information on the index, see Cofelice and Stravridis Reference Cofelice and Stavridis2014, 155–56.)

The five scales seen in Table 1 are used to create an index called parliamentary powers, ranging from 0 to 1, according to the following formula (Cofelice and Stravridis Reference Cofelice and Stavridis2014):

$$\matrix{ {PP = \displaystyle{{{\rm \alpha} C + {\rm \beta} O + {\rm \gamma} A + {\rm \delta} B + {\rm \varepsilon} L} \over {5( {{\rm \alpha} + {\rm \beta} + {\rm \gamma} + {\rm \delta} + {\rm \varepsilon}} ) }}} & {{\rm where}} & {0{\rm} \le C \le {\rm} 5\;{\rm weight} \;\alpha = {\rm} 1} \cr {} & {} & {0{\rm} \le O \le {\rm} 5\;{\rm weight}\;\beta = {\rm} 2} \cr {} & {} & {0{\rm} \le A \le {\rm} 5\;{\rm weight}\;\gamma = {\rm} 2} \cr {} & {} & {0{\rm} \le B \le {\rm} 5\;{\rm weight}\;\delta = {\rm} 2} \cr {} & {} & {0{\rm} \le L \le {\rm} 5\;{\rm weight}\;\varepsilon {\rm} = {\rm} 2} \cr} $$

$$\matrix{ {PP = \displaystyle{{{\rm \alpha} C + {\rm \beta} O + {\rm \gamma} A + {\rm \delta} B + {\rm \varepsilon} L} \over {5( {{\rm \alpha} + {\rm \beta} + {\rm \gamma} + {\rm \delta} + {\rm \varepsilon}} ) }}} & {{\rm where}} & {0{\rm} \le C \le {\rm} 5\;{\rm weight} \;\alpha = {\rm} 1} \cr {} & {} & {0{\rm} \le O \le {\rm} 5\;{\rm weight}\;\beta = {\rm} 2} \cr {} & {} & {0{\rm} \le A \le {\rm} 5\;{\rm weight}\;\gamma = {\rm} 2} \cr {} & {} & {0{\rm} \le B \le {\rm} 5\;{\rm weight}\;\delta = {\rm} 2} \cr {} & {} & {0{\rm} \le L \le {\rm} 5\;{\rm weight}\;\varepsilon {\rm} = {\rm} 2} \cr} $$It is a normalized weighted mean (0 ≤ PP ≤ 1), where C stands for consultative, O for oversight of institutional activities, A for oversight of appointments, B for budgetary, and L for legislative. C has a different weight than O, A, B, and L because all of the latter powers can be considered binding powers, whereas the consultative function of a regional international parliament, by definition, cannot exert binding power on national decision-making bodies (Cofelice and Stravridis Reference Cofelice and Stavridis2014).

Table 1. Components of the Index of Parliamentary Powers

As the units of analysis in this study are countries, for each of the 175 countries, I calculate a sum of the index values of each international parliament to which that country claims membership. This allows me to calculate the impact of multiple memberships. The country with the highest number of memberships is Russia, with six parliamentary memberships (see Table 2). Another 35 countries have no parliamentary memberships; these countries get a score of 0. However, having six memberships does not guarantee the highest score on the scale, because the parliaments of membership might not be very strong on the Index of Parliamentary Powers. For example, although Russia has six memberships, Finland, Denmark, and Sweden have the highest scores in the measurement used here, with four parliamentary memberships each.

Table 2. Distribution of cases according to the number of memberships in ınternational regional parliaments

The rationale for using an additive scale is to capture the absolute additive strength of each parliament, given that there is a wide range of variation in the strength of each parliament. Alternative methods, such as an average or weighted average, would not directly reflect the absolute strength of parliamentary membership but, on the contrary, would reflect an average impact that ignores how many parliamentary memberships the country has. Thus, I avoid using the strategy of taking averages, as it would significantly disadvantage those countries with higher numbers of parliamentary memberships. An additive strategy allows me to treat each parliament at its absolute level of strength—thus, the more parliamentary memberships, the higher the score that a country might get—rather than limiting the upper level of impact of the strength of parliaments. Thus, an additive scaling strategy is chosen as the most suitable method, given that absolute differences in the values are of more interest and importance for this study. As a result, I calculate the strength of memberships in regional international parliaments using a scale ranging from 0 to 1.8; after normalizing, the scale ranges from 0 to 1 with a mean score of .29.

Control Variables

Women's Representation

In the feminist literature, women's representation in national parliaments has often been discussed in terms of the relationship between descriptive and substantive representation. While the former refers to the number of representatives (e.g., the percentage of women in parliaments), the latter is concerned with whether representatives act for the represented (e.g., the adoption of gender equality policies). There are strong arguments supporting the notion that when women are elected to office, they tend to act in the interest of their female constituents (Saint-Germain Reference Saint-Germain1989). Thus, there is a positive impact of descriptive representation on the substantive representation of women (e.g., Atchinson and Down Reference Atchinson and Down2009; Bratton and Ray Reference Bratton and Ray2002; Caiazza Reference Caiazza2002; Chaney Reference Chaney2008; Childs and Withey Reference Childs and Withey2004; Saint-Germain Reference Saint-Germain1989). The literature demonstrates that the increasing representation of women in politics has a positive impact on the adoption of gender equality policies (Atchinson and Down Reference Atchinson and Down2009; Caiazza Reference Caiazza2002; Chaney Reference Chaney2008; Grey Reference Grey2001; Saint-Germain Reference Saint-Germain1989). It makes sense, then, to use the percentage of women's parliamentary representation as a control variable in this study.

Women's representation is measured as the percentage of women in the lower house of parliament as of June 2015. For two countries—Suriname and Ethiopia—data were not available for the month of June, as the elections were newly held. Therefore, for those two countries, I used the data from December 2015. Five countries—Taiwan, Kosovo, Egypt, Central African Republic, and Brunei—were not included in the Inter-Parliamentary Union Database (IPU 2015). Thus, the most recent election results presented by the Gender Quotas Database were used to avoid the missing cases (IDEA 2019b).Footnote 4

Left Party Politics

Numerous studies provide evidence that leftist parties facilitate gender equality to a greater degree than other parties. Strong left-wing parties are considered favorable political structures for gender equality policy creation (Beckwith and Cowell-Meyers Reference Beckwith and Cowell-Meyers2007), while political parties, parliamentary groups, and caucuses with a leftist ideology tend to produce policies in favor of the reconciliation of women's work and home duties, social justice, and gender equality (Caul Reference Caul1999; Kenworthy and Malami Reference Kenworthy and Malami1999; Tripp and Kang Reference Tripp and Kang2008). Reinforcing these arguments, many studies have found that more women are nominated and elected by left-wing parties than by right-wing parties (Beckwith and Cowell-Meyers Reference Beckwith and Cowell-Meyers2007; Duverger Reference Duverger1955; Kenworthy and Malami Reference Kenworthy and Malami1999; Paxton Reference Paxton1997).

That is not to say, however, that gender equality policy occurs exclusively under left-wing party governance. Caul (Reference Caul1999) asserts that support for gender equality policy extends across the “ideological spectrum” and is not exclusively a concern of left-leaning groups and parties. In line with this body of research, it makes sense to include a measure of the degree to which left parties control the government in the analysis of the strength of international regional international parliaments.

The left party variable uses the political orientation of the chief executive's party in 2015, as documented in the Database of Political Institutions 2017 (Cruz, Keefer, and Scartascini Reference Cruz, Keefer and Scartascini2018). In this database, values are assigned on a scale of 0 to 3: 1 represents right-wing affiliation, 2 represents centrist parties, 3 represents left-wing affiliation, and 0 is assigned if there is no information or no party affiliation can be determined. By using these data, a dummy variable is created that gives all 3's a value of 1 and the rest 0. Twelve missing cases were calculated by the author using information for 2015 from the PARLINE Database on National Parliaments (IPU 2019).Footnote 5

Electoral System: Proportional Representation

Electoral systems have an impact on social conditions and women's status, since electoral arrangements are a means to include groups of people in governance (Rule Reference Rule1994). It has been demonstrated that in comparison with plurality-majority systems, proportional representation (PR) is more women friendly in terms of both representation and gender equality policy adoption (Kenworthy and Malami Reference Kenworthy and Malami1999; Matland Reference Matland1998; Paxton Reference Paxton1997; Paxton, Hughes, and Painter, Reference Paxton, Hughes and Painter2010; Reynolds Reference Reynolds1999; Rule Reference Rule1987). The primary argument is that political parties in PR systems have a larger number of seats per district, also referred to as multimember districts, and that increases women's chances of obtaining seats (Kenworthy and Malami Reference Kenworthy and Malami1999; Tripp and Kang Reference Tripp and Kang2008). Plurality-majority systems, on the other hand, tend to have single-member districts, which place an important barrier on female representation (Reynolds Reference Reynolds1999). Moreover, Schwindt-Bayer and Mischler (Reference Schwindt-Bayer and Mishler2005) identify an indirect impact of PR systems on the adoption of women's policies besides its direct impact on women's representation.

The main source for the PR electoral system variable is the IDEA Electoral System Design Database (IDEA 2019a) for 2015. The database has detailed classifications for electoral systems, including different forms of plurality-majority systems, PR systems, mixed systems, and other systems. In this research, a country gets a score of 1 if its national legislature is elected through one of the following systems: list PR, single transferable vote, or mixed-member PR system. This is a dummy variable ranging from 0 (non-PR system) to 1 (PR system).

Economic Development

The relationship between the economy and gender equality policy continues to be the subject of much debate, as it is one of the factors affecting state capacity to adopt and implement gender equality polices, particularly those needing state funding such as violence against women, parental leave, child care, and social security. Economic development, the economic climate of a country, and the economic philosophies dominant in a country all affect policy makers’ tendency to promote gender equality policies (Meehan Reference Meehan1992). Thus, many scholars find that economic development has a positive impact on gender equality policies (Fish Reference Fish2002; Poe, Wendel-Blunt, and Ho Reference Poe, Wendel-Blunt and Ho1997; Sweeney Reference Sweeney2004, Reference Sweeney, Hertel and Minkler2007), while other bodies of literature determine that economic development is linked to women's representation in national parliaments (Hughes Reference Hughes2007; Matland Reference Matland1998; Tripp and Kang Reference Tripp and Kang2008; Viterna, Fallon, and Beckfield Reference Viterna, Fallon and Beckfield2008). Inglehart and Norris (Reference Inglehart and Norris2003) claim that a nation's degree of economic development is critical in explaining gender inequality cross-nationally because modernization processes, accompanied by economic development, shift a society's value of traditional gender roles toward gender equality.

However, it is also argued that “fast-paced, foreign capital-led growth” does not necessarily lead to gender equality, since resources are concentrated on quick growth rather than the “well-being for the most vulnerable” (Fodor and Horn Reference Fodor and Horn2015, 303). Eastin and Prakash (Reference Eastin and Prakash2013) provide evidence that economic development and gender equality are related in a curvilinear fashion—that is, gender equality both improves and deteriorates throughout the process of economic development, rather than improving in a monotonic, unidirectional fashion. In a different vein, Vickers (Reference Vickers2006) argues that certain highly developed countries spend a significant amount of their gross domestic product (GDP) on building military power instead of investing in public health, education, or other social policies that could benefit gender equality. This complex discussion leads us to probe the associations here by including a measure of economic wealth in the multivariate modeling.

The GDP per capita variable (current international dollars) uses 2015 data from the World Bank World Development Indicators Database (World Bank 2015). To account for factors such as population size, I use GDP per capita as opposed to GDP to gauge a country's economic climate. In the database, information for Eritrea, Syria, and Venezuela was not available for 2015. Therefore, the latest available data point is taken for those countries: 2011 for Eritrea, 2007 for Syria, and 2014 for Venezuela. Moreover, data were unavailable for North Korea and Taiwan. For these two countries, CIA World Factbook 2015 estimates are used to avoid missing cases. By using these data, this variable is calculated as a natural logarithm of GDP per capita for each country.

Level of Democracy

Research strongly suggests that democratic states are consistently more likely to support women's rights. Although democracy does not imply the protection of human rights automatically, modern democratic states with political and civil freedoms, including an active civil society as well as free and fair elections, are more likely than any other type of political regime to support and promote women's rights and gender equality (Sweeney Reference Sweeney2004, 14). In their examination of the success of women's rights, Eastin and Prakash (Reference Eastin and Prakash2013) point to the significant relationship between democracy and gender equality. Furthermore, some studies demonstrate that involvement of enhanced pluralist civil society during transitions to democracy prompted the adoption of gender-sensitive policies (Guzman, Seibert, and Staab Reference Guzmán, Seibert and Staab2010; Waylen Reference Waylen2008).

Furthermore, marginalized groups, including women or ethnic minorities, have more opportunities to participate in the governance of democratic countries, as their political systems and institutions allow civil society movements. Therefore, democracy is considered a precondition for the adoption of gender equality policies and for the implementation of those policies. Some large-N comparative studies investigating the effect of women's political representation on democracy were not able to show such a positive statistical association but, on the contrary, weak, negative, or statistically insignificant results (Kenworthy and Malami Reference Kenworthy and Malami1999; Paxton Reference Paxton1997; Tripp and Kang Reference Tripp and Kang2008). Given the mixed picture, I include a measure of democracy in the multivariate modeling.

To measure each country's degree of democracy, Freedom House's indicator of democratic political rights is adopted. These scores are derived by combining various indicators. Using Freedom House's 2015 data, the variable is measured on a scale of 1 to 7, where 1 is the most free and 7 is the least free.

Religion

The relationship between women's rights and the separation of state and religion has been frequently investigated. The incorporation of religious norms into law results in the institutionalization of patriarchal religious norms within the government apparatus, thus affecting the manner in which a state frames its legislation, policies, and actions toward women (Spierings, Smits, and Verloo Reference Spierings, Smits and Verloo2008). Furthermore, governments that see religion as an intimate component of the policy-making process are less likely to protect women's rights and, in fact, more likely to introduce oppressive practices against women (Sweeney Reference Sweeney2006, vi, 5). In a later study, Sweeney (Reference Sweeney2014) again found that institutional secularism is a significant predictor of women's rights.

At the same time, many studies challenge this relationship. Looking at Islam as an example, Price (Reference Price2002) finds that Islamic dictators do not necessarily violate human rights—including women's rights—more than non-Islamic or secular Muslim dictators. Weldon (Reference Weldon2002) provides the example of Ireland's government, a body deeply intertwined with Catholicism, which reacted to domestic violence issues with a much more responsive policy than Italy's secular government. Furthermore, Bernstein and Jakobsen (Reference Bernstein and Jakobsen2010) argue that in the case of the United States, the forces that promote gender equality are both secular and religious—therefore, it is unwise to immediately conclude that the religious impact on women's rights is always negative and conservative.

Nonetheless, religious institutions are particularly disposed to regulate issues of sexuality and reproduction, family and kinship relations, and marriage (Jamal and Langohr Reference Jamal and Langohr2010; Razavi and Jenichen Reference Razavi and Jenichen2010), all of which are tied closely to the rights of women. Thus, in this study, it is expected that the degree of secularist or Islamic influence on a country's government will affect gender equality policies.

To measure secularism, I use the indicator official support for religion, which measures the degree of hostility or support a government displays for religion. This is a 14-point scale ranging from 0 to 13, where 0 represents “specific hostility” toward religion with “overt persecution,” 4 represents a neutral “accommodation” of religion, and 13 represents “mandatory religion for all” (Fox Reference Fox2017). Data were pulled from the Religion and State Project Round 3 and come from 2014 or the latest possible time point.

A dummy variable was created for Muslim-majority countries. The data for this variable derive from the most recent data points in the CIA World Factbook (CIA 2015).

DESCRIPTION OF GOVERNMENT POLICY FRAMEWORK FOR GENDER EQUALITY SCALE

Table 3 presents descriptive statistics on the components of the government policy framework for gender equality scale. The results for all components include 176 countries. The mean for the first component, legal declaration of gender equality, is 1.04. The mean for the second component is 1.49, indicating that countries adopt a greater number of action plans than legal declarations. The mean for the third component, commitment to the international gender equality regulation, CEDAW, is 2.03 on a 3-point scale, indicating a positive trend in ratifying CEDAW.

Table 3. Descriptive statistics for government framework for gender equality scale

Note: N = 176.

Table 4 demonstrates the association between the three components of the scale. The standard methods of performing Pearson's correlations assume that the analysis is run with continuous variables that follow a multivariate normal distribution. A polychoric correlation can also be used with ordinal variables. Thus, a polychoric correlation was run to see the relationship between the three components. The correlations between the three components are between .23 and .31, indicating a positive correlation between the three indicators.

Table 4. Polychoric correlation matrix for government policy framework for gender equality indicators

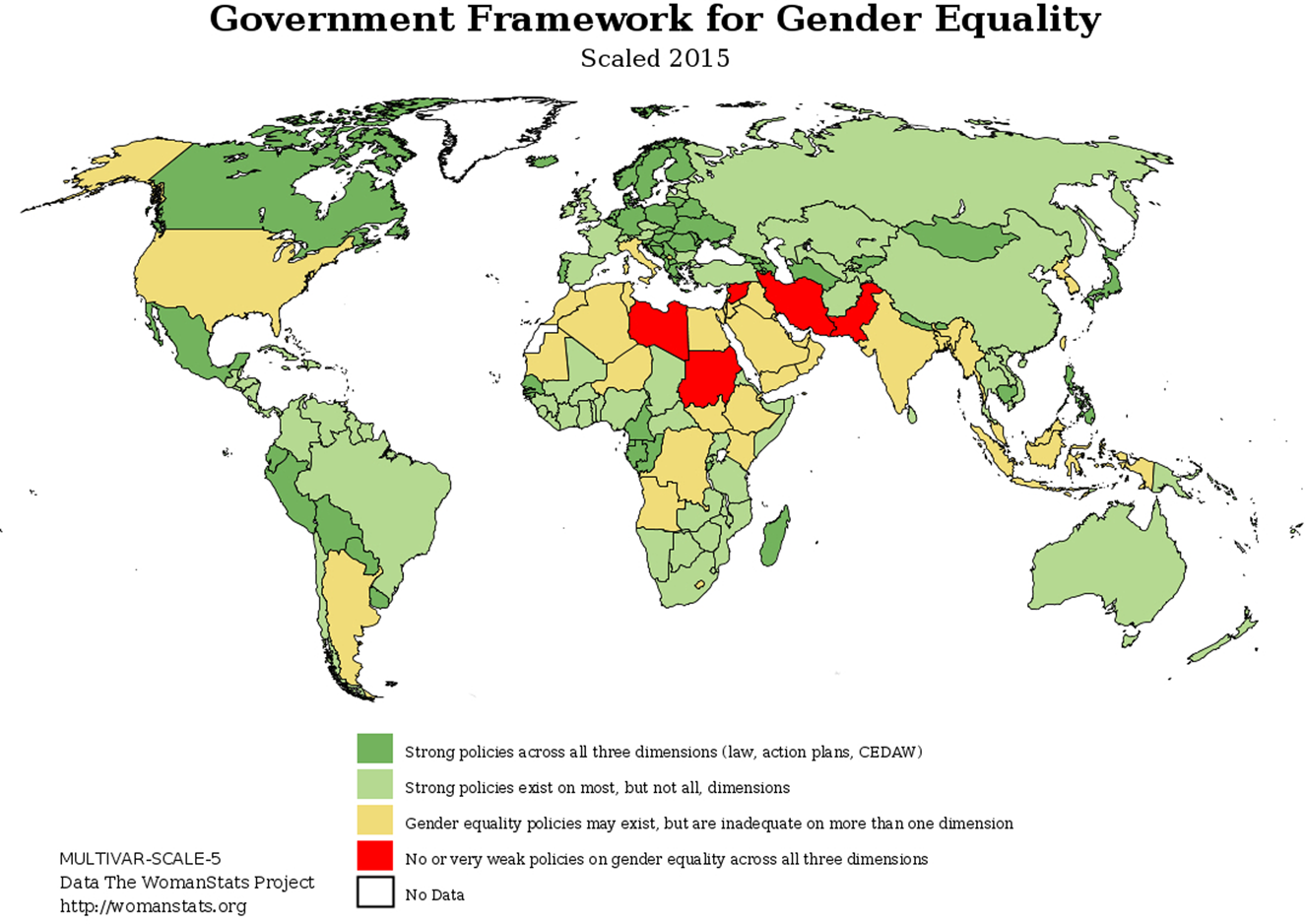

Figure 1 presents country results for the government policy framework for gender equality scale. As the map demonstrates, five African and Middle Eastern countries are scaled as having very weak policies: Syria, Iran, Pakistan, Libya and Sudan. Countries from Europe as well as Latin America and Africa are adopting strong Blueprint policies. Fifty-four countries achieved the highest rank, indicating good country performance on Blueprint policies. The mean level for the government policy framework for gender equality scale for all countries is 4.57 with a maximum of 7 points, indicating that countries on average adopted strong policies across the world. However, one should keep in mind that “governments adopt Blueprint policies far from the public view and do little, if anything, to implement them” (Mazur Reference Mazur2002, 47). Thus, even though the map suggests many countries are performing well in adopting policy frameworks for gender equality, this is not always the case when looking at specific issues of gender equality.

Figure 1. Government framework for gender equality scale (scaled 2015). Source: Reprinted with permission from the WomanStats Project, http://www.womanstats.org/maps.html.

An interesting point to note from the map is that the United States and Italy are represented as adopting inadequate government policy frameworks for gender equality. The United States tends to perform poorly, as CEDAW was not ratified by its government. Italy also earns a score of 1 from the CEDAW indicator, as Italy has reservations regarding CEDAW. Looking at the scale points in Table 5, I can state that the scale is positively skewed, showing that more countries have medium or high scores.

Table 5. Score distribution of government policy framework for gender equality scale

RESULTS

Table 6 presents the results of the ordinary least squares (OLS) and ordered logistic regressions. In Model 1, OLS regression was run, as the dependent variable of the analysis is measured using a continuous scale. However, OLS regression analyses are problematic when the dependent variable has an ordinal measurement, because the OLS method cannot produce the best linear unbiased estimator (Lu Reference Lu1999). Ordinal logistic regression is one of the most widely used methods for ordinal-level dependent variables (Park Reference Park2009). Ordinal logistic analysis is applied in Models 2, 3, and 4 because of the ordinal-scale characteristics of the dependent variables.

Table 6. OLS and ordered logistic regression results of the impact of international parliaments on government policy framework for gender equality

Notes: Coefficients are presented and t-statistics are in parentheses. Palestine was dropped from the model because of a high degree of missing data in the control variables.

*p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001.

Model 1 was run with the dependent variable of the composite scale for government policy framework for gender equality. The model indicates that three variables have a significant impact (p < .05 or lower) on the government policy framework for gender equality: the strength of membership in regional international parliaments, the level of economic development, and the level of Islamic influence on a country's society and politics. The statistically significant positive coefficient for membership in and strength of regional international parliaments shows a positive association between the strength of membership in regional international parliaments and the government policy framework for gender equality. The influence of Muslim culture on a country's society and political environment has a strong negative impact on the adoption of a government policy framework for gender equality, meaning that Muslim-majority countries are less keen on adopting legal frameworks and supporting CEDAW. On the other hand, the negative coefficient for economic development shows that the level of wealth in a country significantly reduces the adoption of a government policy framework for gender equality. This result might be due to higher GDP per capita levels of rentier and oil-producing countries, which are mostly Muslim-majority countries and have poor records on government policy frameworks for gender equality, such as Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, and Kuwait. In addition, wealthier countries might attach less importance on international pressures to improve their government policy framework for gender equality and thus, do not hesitate to reject ratification of CEDAW, such as the United States, or made significant reservations, such as Switzerland or United Kingdom.

Model 2 presents the results of the ordered logistic analysis of the first component, legal declaration of gender equality. The positive coefficient for the strength of regional international parliaments indicates that stronger regional international parliaments increase the likelihood of having a legal declaration of gender equality. On the other hand, the negative coefficient for predominantly Muslim country demonstrates that being a Muslim country significantly reduces the likelihood of adopting a legal declaration for gender equality. This empirical finding might demonstrate that Muslim culture somehow has a detrimental impact on declarations of gender equality and sex discrimination in legal systems.

Model 3's only significant variable in determining the adoption of action policies is the variable concerning the strength of membership in regional international parliaments. This is an important finding, as it is the only significant variable that has an impact on the policy action variable. This indicates that regional international parliaments have a significant impact on the adoption of gender equality action plans and, consequently, serve as important tools in the improvement of gender equality. As previously mentioned, many regional international parliaments develop regional strategic plans, action plans, and agendas and set gender equality as an important part of their development goals. Moreover, they organize meetings and forums to develop such plans and seek ways to implement gender equality policies. These strategies put pressure on national governments to adopt national action plans that improve gender equality.

In Model 4, only three statistically significant variables—the strength of the regional international parliaments a country belongs to, the country's level of economic development, and being a predominantly Muslim country—affect commitment to the international gender equality framework. The negative coefficient for GDP per capita demonstrates that many countries that put reservations on CEDAW have higher levels of economic development. This finding is not surprising because many countries with high levels of GDP per capita, such as the United States, Ireland, Italy, and Switzerland, and rentier states, such as Qatar, United Arab Emirates, and Brunei, either have not signed CEDAW or have put reservations on it. In addition, the negative coefficient for predominantly Muslim country variable demonstrates that being a Muslim country significantly reduces the likelihood of adopting international standards for gender equality. The Muslim-majority states particularly prefer to put reservations on CEDAW articles, as their constitutions, customary laws, or cultural norms might not allow the implication of some of the international gender equality norms. I argue that those norms that are related to the private sphere of life would face more resistance in Muslim societies than public issues (Jamal and Langohr Reference Jamal and Langohr2010).

In short, the variable of strength of membership in regional international parliaments is the only robust factor that impacts the composite scale as well as its components. This confirms that regional international parliaments have a positive impact on national governments, pushing them to adopt better government policy frameworks for gender equality.

CONCLUSION

This article has probed whether the strength of membership in regional international parliaments to which a country belongs plays a significant role in its developing a successful government policy framework for gender equality. An empirical analysis of 175 countries demonstrated that regional international parliaments are crucial actors in the adoption of government policy frameworks for gender equality. Both in the composite scale and the components of the government policy framework for gender equality scale, the impact of international regional parliament membership appears to be robust. Thus, the main implication of this study is that regional international parliaments impose different types of gender equality regulations on national governments to improve their policy frameworks for gender equality. They can apply a variety of effective mechanisms and tools, such as establishing women's policy agencies, organizing forums and trainings, issuing written reports, preparing strategy documents and actions plans, and/or publishing gender-sensitive data and statistics.

This study demonstrates that these mechanisms are important tools when regional governments have stronger legislative, budgetary, appointment, oversight, and consultative powers. These findings are significant because, in our current and increasingly globalized world, it is necessary to acknowledge that international parliaments and the international community can pressure national governments, leading them to actively address gender equality issues and adopt better policy framework for gender equality. Internationalization might be an important first step in creating a gender-equal governance system and women-friendly legal statutes. Therefore, strengthening the powers of existing international parliaments may benefit the relevant governments’ policy frameworks for gender equality.

However, as discussed in Ertan (Reference Ertan2016) and Kabeer (Reference Kabeer2005), gender inequalities are multidimensional, and improvement in one dimension does not guarantee improvement in another dimension. Thus, I argue that improving government policy frameworks is just the first step in the improvement of gender equality and women's empowerment. Application of the government policy frameworks for gender equality to other legal frameworks and to domestic legislation is also crucial to the implementation of those policy frameworks. Even once a state completes gender equality in the legislative area, this does not ensure de jure changes in women's lives and real empowerment of women. Thus, real empowerment of women, although affected by government policy frameworks and laws, only occurs with the internalization of gender equality norms by the majority of society. In Kabeer's words, “Empowerment is rooted in how people see themselves—their sense of self-worth. This in turn is critically bound up with how they are seen by those around them and by their society” (Reference Kabeer2005, 15).

This study also demonstrates that being a Muslim-majority country significantly reduces the likelihood of having a government policy framework for gender equality. As far as secularity does not appear to be a significant factor, one can argue that cultural norms accepted in Muslim societies seems to be the main factor that is detrimental on government policy frameworks for gender equality. Besides cultural norms, in some of the Islamic states, such as Iran and Saudi Arabia, there might be a negative impact of the Islamic and customary law systems, which might not allow the adoption of universal women's rights norms and gender equality principles. Therefore, those who advocate for gender equality within Muslim societies will need to find appropriate ways to incorporate gender equality principles into government action.

Economic development, on the other hand adversely, affects gender equality, as higher economic development decreases the likelihood of developing a successful government policy framework for gender equality. Development level, as measured by GDP per capita, has a negative impact on the adoption of CEDAW. This may be because many countries that put reservations on CEDAW have high GDP per capita levels, such as Luxembourg, Monaco, Qatar, Brunei, United Arab Emirates, and Singapore.