As the first country in the world to legislate candidate gender quotas in 1991, Argentina provides a compelling case for re–examining the relationship between women's descriptive representation (women's presence in politics) and women's substantive representation (the promotion of women's interests). Although the comparative literature on gender quotas has grown substantially in recent years, the main focus has been on quotas’ adoption, namely why countries choose quotas and how quotas improve women's election.Footnote 1 Fewer studies have explored the impact of quotas on the representation of women's interests, or, more precisely, whether quotas enable or encourage female politicians to promote women's rights. Conversely, the literature on women's substantive representation has not taken into account the global diffusion of legislated candidate gender quotas, now in place in 42 countries worldwide.

Gender quotas take a number of forms. Party quotas are voluntary measures adopted by political parties to increase female candidates, reserved seats set aside a certain number of seats for women, and legislated candidate gender quotas require all political parties to nominate a minimum percentage of female candidates. Political parties and national legislatures in at least a hundred countries worldwide have either adopted or debated the adoption of some form of gender quotas (Krook Reference Krook2007, 367). In this article, we use “gender quota” or “quota” to mean legislated candidate gender quotas.

Gender quotas are explicit measures that target gender bias in the candidate selection process, with the goal of increasing women's descriptive representation. Embedded in most quota campaigns is the consequentialist argument that quotas will improve the representation of women's interests. Theoretical defenses of gender quotas thus assume a link between descriptive and substantive representation. It is therefore important to explore how gender quotas, once incorporated into political institutions, mediate the relationship among women's presence, their likelihood to act for women, and their success. We suggest that ballots that legally require women's presence create both opportunities for and potential obstacles to women's substantive representation. Quotas create what we call a “mandate effect,” whereby female legislators perceive an obligation to act on the behalf of women. More problematically, quotas may also encourage beliefs that women elected under quota systems are less experienced and less autonomous. While not necessarily factually accurate, these beliefs nonetheless generate stereotypes about “quota women” that negatively affect how female legislators are received and regarded by their colleagues. We term this phenomenon a “label effect.”

Our analysis of the Argentine case is rooted in the comparative literature on women's representation, with the goal of theory building about how descriptive and substantive representation connect in practice. In our view, much of the existing literature conflates two distinct aspects of substantive representation: the process of acting for women and the fact of changing policy outcomes. Acting for women occurs when female legislators introduce bills that advance women's interests, bring gender perspectives into legislative debates, and network with women inside and outside of the Argentine Congress. These actions do not always bring about dramatic policy changes. In this article, our goal is to analyze how gender quotas, by creating mandates and labels, interact with the institutional environment to affect how and why women act for women, and also how and why women's actions succeed or fail.

The article is divided into three sections. First, we offer both an overview of the existing literature and an account of why scholars have reached different conclusions about the link between women's descriptive and substantive representation. We argue that the absence of scholarly consensus has developed because researchers 1) use different operationalizations of the variables and 2) place different weight on the institutional environment. Second, we draw on the existing literature about quotas to generate some hypotheses about the ways in which gender quotas may influence women's substantive representation. Third, we explore the Argentine case, where legislation adopted in 1991 requires that women hold at least 30% of electable spots on all party lists. This law (Ley de Cupos) has been effective: As we discuss in more detail later, women now hold more than 35% of seats in both chambers.

We show that gender quotas in Argentina have affected women's substantive representation in contradictory ways. The quotas did give female legislators a mandate to change policy. Mandates developed through quota campaigns; although advocates justified quotas by referencing gender equality and democratic fairness, many arguments also invoked beliefs about women's sociocultural roles that reinforce notions of women's difference. More problematically, however, quotas also generated a perception that “quota women” needed special treatment. We argue that female legislators’ response to labels and mandates varies, and that this variation shapes how substantive representation occurs both as process and as outcome. We find that quotas in Argentina have improved women's substantive representation as process. There has been a significant increase in the number of women's rights bills introduced into the Argentine Congress, with the vast majority introduced by women. In terms of changing outcomes, we find that legislative success depends on action (that women engage in a process of substantive representation) and context (the environment in which the process unfolds). We find that quotas do not change the institutional features and gender bias in the legislative environment, and therefore do not enhance women's ability to transform policy outcomes.

DEBATING THE DESCRIPTIVE-SUBSTANTIVE LINK IN WOMEN'S REPRESENTATION

Most scholars take Hanna Pitkin's (Reference Pitkin1967) classic work on representation as a starting point, distinguishing between legislators who are descriptively similar and therefore “stand for” their constituents, and those who substantively “act for” constituents by promoting issues of concern to that group. For some theorists, the problem with linking descriptive and substantive representation is the flawed assumption that descriptive similarity, that is, sharing ascriptive features, leads automatically to substantive similarity, that is, sharing perspectives and interests. In other words, the idea that female politicians are needed to represent women's interests assumes a homogeneity among women that reinforces essentialist notions of an exogenously given, universally shared, fixed female identity.

Contemporary scholars sidestep these charges by conceptualizing the articulation of women's interests as a fluid process. First, women's identities are multiple, constituted not only by gender but also by ethnicity, race, class, and sexual orientation. Second, women can share a female perspective independent of, and not reliant upon, any essential female identity (Young Reference Young2000). Third, sociohistorical patterns of marginalization suggest that male perspectives are generally those heard in public: A range of experiences by women-as-group and women-as-differentiated-individuals have been denied political weight. Indeed, Virginia Sapiro (1995), Anne Phillips (Reference Phillips1995), and Jane Mansbridge (Reference Mansbridge1999, Reference Mansbridge2005) all argue that instances where the group's interests are unclear, unformed, or contested are precisely those instances where descriptive representation becomes necessary. Shared perspectives increase the likelihood that some shared interests can be articulated by group members.

We can thus analyze women's representation without falling into the essentialist trap of claiming that group interests derive automatically from identity. This formulation addresses concerns that individuals cannot speak for groups. Laurel Weldon explains, for instance, that “[i]f she is a white, straight, middle-class mother, she cannot speak for African-American women, or poor women, or lesbian women on the basis of her own experience any more than men can speak for women merely on the basis of theirs” (2002, 1156). She further claims that, even if a representative could speak for the group—meaning that the representative participated and shared in group life—the representative would still only articulate one “puzzle piece” of group interests. Weldon worries that individual representatives can never understand the whole picture of group interests (2002, 1156–59). Yet the link between descriptive and substantive representation does not require a one-to-one correlation between being like and speaking for. Shared interests simply broaden the agenda. Consequently, representatives need not invoke whole pictures: Puzzle pieces alone make it likely that matters of concern to multiple and diverse groups of women are heard.

We thus distinguish between the process-oriented and outcome-oriented aspects of representation. Women's substantive representation as process occurs when legislators undertake activity on behalf of some or many women. These actions include introducing and/or supporting bills that address women's issues, establishing connections to female constituents or women's organizations, networking with like-minded colleagues, or putting women's issues on the agenda within committees or party delegations.Footnote 2 Substantive representation thus requires that legislators have certain attitudes and preferences when acting as representatives; these activities then increase the likelihood that transformative outcomes to institutions and policies occur. Essentially, substantive representation as process may appear without resulting in substantive representation as outcome. Transforming political practices and winning new policies are certainly commendable instances of substantive representation as outcome, though they are not necessary for representation itself to occur.

This twofold conceptualization of women's substantive representation encourages researchers to look beyond mere numbers. Indeed, “critical mass” theories are problematic: The assumption that there exists a threshold percentage, which, when reached, allows female legislators to transform politics has been strongly criticized in recent years. Some have noted that critical mass theories, by expecting female legislators to collectively transform policies, place an undue burden on newly elected women (Trimble Reference Trimble, Sawer, Tremblay and Trimble2006, 127). Others have emphasized the myriad intervening variables that determine whether, when, and how women can achieve policy change that benefits women as a group (Beckwith Reference Beckwith2007; Childs and Krook Reference Childs and Krook2006; Dahlerup Reference Dahlerup2006b).

Testing critical mass empirically is also problematic. While much of the research on women in legislatures is quite optimistic, finding that female legislators act for women (Carroll Reference Carroll and Carroll2001; Poggione Reference Poggione2004; Tamerius Reference Tamerius, Duerst-Lahti and Kelly1995; Taylor-Robinson and Heath, Reference Taylor-Robinson and Heath2003; Thomas Reference Thomas1994; Vega and Firestone Reference Vega and Firestone1995; Wängnerud Reference Wängnerud2005; Wolbrecht Reference Wolbrecht and Rosenthal2002), other recent research findings are skeptical about an automatic link between descriptive and substantive representation (Childs Reference Childs2004; Dodson Reference Dodson2006; Grey Reference Grey, Sawer, Tremblay and Trimble2006; Htun and Power Reference Htun and Timothy2006; Reingold Reference Reingold2000; Schwindt-Bayer Reference Schwindt-Bayer2006; Tremblay and Pelletier Reference Tremblay and Pelletier2000; Vincent Reference Vincent2004; Weldon Reference Weldon2002). We argue that variation in research findings is due to two factors.

First, much of the variation occurs because researchers define women's substantive representation in dissimilar ways, and employ different indicators to measure the link between descriptive and substantive representation. Too many studies conflate women's substantive representation as a process, that is, women acting for women, with substantive representation as an outcome, that is, women changing policy. Process-focused studies ask whether gender differences in legislators’ attitudes and activities change the issues represented in the chamber. Outcome-focused studies capture different dependent variables, looking either to changes in political practice (for example, decreasing gender discrimination in politics) or to changes in public policies (adopting women-friendly legislation) (cf. Dahlerup Reference Dahlerup2006b). While studies of legislator attitudes and behavior often find that there are differences between male and female legislators, scholars focusing on outcomes often find that women's presence has neither empowered women as political actors nor dramatically transformed public policy. Thus, a focus on legislator behavior often yields more optimistic conclusions than does a focus on legislative outcomes.

Second, not only are scholars focusing on different variables, but they are also using different indicators to measure substantive representation. Most of the “optimists” use bill introduction and cosponsorship to operationalize gender differences in legislator behavior. Studies from the United States, Latin America, and Africa find that female legislators are more likely than their male counterparts to introduce and cosponsor legislation that deals with women's rights and children and families (Bratton Reference Bratton2005; Bratton and Ray Reference Bratton and Ray2002; Carroll Reference Carroll and Carroll2001; Jones Reference Jones1997; Schwindt-Bayer Reference Schwindt-Bayer2006; Swers Reference Swers2005; Tamerius Reference Tamerius, Duerst-Lahti and Kelly1995; Taylor-Robinson and Heath Reference Taylor-Robinson and Heath2003; Thomas Reference Thomas1994; Vega and Firestone Reference Vega and Firestone1995; Wolbrecht Reference Wolbrecht and Rosenthal2002). Yet bill introduction only captures the procedural aspects of substantive representation; it reveals nothing about policy outcomes. While the findings tend to be positive—female and male legislators often manifest different legislative priorities—we caution against conflating such differences with women's substantive representation as outcome.

Other scholars use survey data to assess legislator attitudes and beliefs: Again, the assumption is that different preferences will yield different outcomes. These studies produce mixed findings. Some find that party membership is a better predictor of support for women's rights policies than legislators’ sex (Poggione Reference Poggione2004; Tremblay and Pelletier Reference Tremblay and Pelletier2000). Using survey data from Brazil, Mala Htun and Timothy Powers (2006) conclude that those hoping for progressive gender policy change should focus their efforts on electing left-leaning parties, because leftists (rather than female legislators) have feminist attitudes. Susan Carroll (Reference Carroll and Carroll2001, 13) likewise concedes that party membership trumps sex when determining legislator attitudes, but adds that women in conservative parties are still generally more progressive on gender issues than their male counterparts. Optimistic or skeptical findings notwithstanding, legislator attitudes are problematic measures of substantive representation: Beliefs do not translate automatically into action, and actions do not translate into policy change. Legislators’ attempts to represent women will be mediated by the norms and procedures that shape the institutional environment, a contextual effect addressed later.

Another problem occurs when scholars believe they can capture substantive representation with just one indicator. Studies that measure policy attitudes or bill introduction are conflating differences between male and female legislators with women's substantive representation (Dahlerup Reference Dahlerup2006b; Dodson Reference Dodson2006, 27). Single indicators are problematic for two reasons: First, the measurement divorces legislator behavior from its institutional context, and second, substantive representation is far too complex to be captured by a single variable. Looking only at bill introduction means that we cannot know whether women's actions were successful. Looking only at policy outcomes tells us little about why these outcomes fail to change: We do not know whether female legislators took no action, or whether they sought change but were unsuccessful. Demanding that female legislators guarantee a connection between substantive representation as process (action) and substantive representation as outcome (change) holds these women, often political newcomers, to unrealistically high standards of success. Sarah Childs (Reference Childs2006, 9) usefully distinguishes between the “feminization of the political agenda (where women's concerns and perspectives are articulated) and a feminization of legislation (where output has been transformed).” It is important to note that women may feminize legislative agendas within institutional environments that undermine their effectiveness. Hence, researchers should ask why female legislators experience success as well as defeat.

Exploring the disconnect between legislators’ actions and policy outcomes requires a closer look at context. Institutions govern actors’ decisions by establishing norms and rewarding certain behaviors. The practices in political institutions have functionally adapted to men. Professional networks, bargaining rules, and meeting times and locations presume that politicians are “one of the boys”: loyal, forceful, and without domestic responsibilities (Htun forthcoming). Lyn Kathlene (Reference Kathlene1994) argues, for instance, that male legislators are verbally aggressive and domineering in committee debates, thereby reducing congresswomen's spoken participation. Overall, the gender-biased legislature means that women are not equal players in the policymaking game (Duerst-Lahti Reference Duerst-Lahti, Thomas and Wilcox2005). Power accumulation for women further entails gender biases: Women embracing masculine norms and male policy domains are accused of failing to represent women, while women remaining feminine or female-focused lose the status required to legislate successfully. Female legislators can thus substantively represent women in contexts where some, or even all, of their transformative efforts fail.

This interaction between gender norms, on the one hand, and institutional rules, on the other, leads many scholars to be skeptical about the link between descriptive and substantive representation. Analyzing the South African case, Louise Vincent argues that “[p]recisely those features of society which lead to the distortion [of numerical representation] in the first place, make it impossible for the presence of women, in the absence of other far-reaching measures, to make much difference at all” (2004, 73). Likewise, Rosemary Whip (Reference Whip1991), commenting on the Australian case, argues that male-defined priorities are so deeply engrained in legislative institutions that ambitious women will rationally avoid legislating in low-prestige policy areas, such as women or family issues.Footnote 3 These contextual details are often obscured by empirical studies that take single indicators, such as attitudes or bill introduction, as a measure of substantive representation. Acknowledging and analyzing gender biases are critical if we want to know how institutions affect representation. The diffusion of gender quotas around the world creates further complexity: As the Argentine case shows, gender quotas influence the relationship between women's presence and substantive representation.

GENDER QUOTAS AND THE LINK BETWEEN DESCRIPTIVE AND SUBSTANTIVE REPRESENTATION

Candidate gender quotas, when legislated at the national level, obligate party leaders to nominate certain percentages of women, in some cases mandating specific placement on party lists. When candidate selection is centralized in the hands of party leaders, as in many proportional representation systems, legislators’ need for future resources ensures party discipline, thereby undermining legislator autonomy (Jones Reference Jones2004). The existence of quotas further affects legislators’ maneuverability: Party leaders may begrudge the women their ballot positions, male colleagues may perceive special treatment, and female constituents may develop high expectations. On the other hand, the greater presence of women might lead, over time, to a greater acceptance of women's changing social roles. As we will discuss, these effects are contradictory and (paradoxically) occur simultaneously.

While the literature on quotas has not looked specifically at the impact of quotas on women's substantive representation, existing research does discuss some of their general effects (Dahlerup Reference Dahlerup2006a). As Mansbridge notes, “[q]uotas tend to reinforce the existing human cognitive tendencies to see the members of the group as more similar than they are and more different from members of other groups” (2005, 632). We believe that the re-inscription of group difference has consequences for women's substantive representation. First, quotas contribute to the perception that female representatives are needed because of their distinctly feminine perspectives. Female legislators may thus feel an obligation to act for women; we identify this perception as a mandate effect. Second, and in contrast, women may reject this mandate, especially those who reject quotas’ implications of special treatment in the first place.Footnote 4 Much of the comparative literature on quotas makes reference to the potential for quotas to create a demeaning belief that “quota women” are undeserving or underqualified (Chowdhury Reference Chowdhury2002; Dahlerup 2006a; Nanivadekar Reference Nanivadekar2006; Tripp Reference Tripp2003; Zetterberg, forthcoming). We identify this stereotype as a label effect. Mandates are created during campaigns for quota adoption, and their strength depends on activists’ justifications for, and degree of mobilization around, quotas. Labels emerge out of adoption and implementation processes and depend on perceptions about political actors’ responses to the new legal requirements.

The success of quotas—in terms of empowering female officeholders—has often varied according to the degree of adoption pressure applied by international actors and domestic advocates (Krook Reference Krook2007). Since the Fourth World Conference for Women in Beijing in 1995, the international community has encouraged new democracies to pass gender equity laws and policies, which include legislated, national-level gender quotas. For postconflict states and young democracies, quota laws—in proclaiming gender equality—signal the countries’ commitment to modernity and stability (Baldez Reference Baldez2006; Dahlerup Reference Dahlerup2006a; Towns Reference Towns2003). In these top-down instances, where calculating political elites adopt quotas for publicity purposes, the mechanisms are less likely to empower women. Alternatively, in bottom-up instances, where domestic advocates (party militants and women's movements) loudly demand quotas, they are more likely to empower women. In our formulation, the top-down or bottom-up instances can affect how female legislators undertake substantive representation.

Legislated quotas shape substantive representation as process, that is, whether female legislators undertake actions on behalf of women (actions which may or may not lead to transformed policy outcomes). Mandates are one strong predictor of whether female legislators act for women. Mandates depend on 1) pressure for quotas coming from domestic constituencies (rather than from international organizations), and 2) the arguments employed by quota advocates. Where quotas are adopted top down, low domestic mobilization may decrease female legislators’ perceived obligation to represent women as a distinct constituency. In these instances, legislators may develop an attachment to quotas in order to preserve their power, but they will not necessarily develop commitments to women in civil or political society.Footnote 5 Where quotas are adopted through and because of domestic lobbying, however, female legislators may attribute their electoral gains to the collective efforts of female activists. This latter scenario generates stronger mandate effects. Moreover, while some arguments supporting quotas emphasize democracy and modernity (via gender equality), others highlight the transformative consequences of women's increased political presence. Mandate effects are intensified when advocates use the latter arguments. These consequentialist appeals are less gender neutral, for they imply that women will articulate different perspectives and different priorities.

Whereas mandates positively affect women's substantive representation, labels have more ambiguous consequences. How women achieve office shapes perceptions about their capabilities. Elite women initially benefited the most from quotas, as in Mexico (Baldez Reference Baldez2004; Rodríguez Reference Rodríguez2003, 143). Unfortunately, party leaders’ rational strategies of nominating female elites became subject to negative interpretations: Observers feared that women, in being exempted from competition, were receiving special treatment and/or were being rewarded beyond their qualifications. In South Africa, for instance, observers allege that the ruling African National Congress applies a party quota by selecting women whom party leaders believe to be pliable (Vincent Reference Vincent2004, 76). Similar concerns about party leaders’ selection of biddable loyalists have been raised in Argentina (Piscopo Reference Piscopo2006; Waylen Reference Waylen2000), Peru (Schmidt Reference Schmidt2003), and Uganda (Tripp Reference Tripp2003; Reference Tripp, Bauer and Britton2006). In India, Medha Nanivadekar (Reference Nanivadekar2006) claims that women elected under quotas are often stand-ins for male relatives. In all cases, the nomination practices can create the demeaning notion that “quota women” are unnecessarily privileged, less capable, and blindly loyal to male party bosses. Even though many male and female candidates are chosen for their loyalty, we contend that the labeling of “quota women” creates double standards: Women, but not men, must prove capacity while disproving nepotism (cf. Dahlerup Reference Dahlerup2006a). Such double standards reinforce the gender bias in legislative institutions.

The overall acceptance of quotas in political society also shapes label effects. Drude Dahlerup and Lenita Freidenvall (2005) identify two pathways to quotas: the incremental track and the fast track. In Scandinavian countries, the incremental track entailed political leaders’ belief that modernization would gradually correct the problem of women's absence from politics; policymakers merely recruited more women as party militants and applied quotas for party leadership positions. The fast track, by contrast, evinces political leaders’ unwillingness to wait; elites may doubt that modernization will occur, or elites may believe that “historical leaps in women's representation are necessary and possible” (Dahlerup and Freidenvall Reference Dahlerup and Freidenvall2005, 29). Fast-track countries impose quotas overnight (directly legislate equality), rather than allow nondiscrimination policies to evolve over time (wait for cultural change). Latin American and African countries have taken the fast track, seeking to immediately transform the gender distribution of political power. The downside to quotas as fast-track mechanisms, however, is greater resistance among the status quo–oriented factions of the political elite. Greater resistance results from party leaders’ frustration at being legally obligated to change their nomination practices, and may deepen the double standards confronted by women elected under quotas.

Argentina therefore presents a paradox: Although a domestic constituency mobilized to support quotas, quotas were implemented as a fast-track mechanism. Descriptive representation increased rapidly, with the support of women across the political spectrum but without an underlying cultural shift that supported women's accumulation of political power. The post-quota institutional environment in Argentina therefore includes both mandate and label effects. The mandate effect, in emerging from domestic groups’ enthusiasm for quotas, increases the likelihood that female politicians feel obligated to undertake the substantive representation of women. Mandates can affect process, as certain female legislators will—and do—make women's well-being central to their legislative goals. The label effect, by contrast, suggests that female politicians will be treated unequally by their peers; double standards affect beliefs about representatives, and beliefs can affect how substantive representation unfolds. Female legislators distancing themselves from the “quota women” stigma may be less willing to act for women, and may be less willing allies to their female-friendly colleagues.

QUOTAS AND WOMEN'S REPRESENTATION IN ARGENTINA

Argentina offers an opportunity to explore the link between quotas and women's representation. The Ley de Cupos was passed in 1991 and initially applied only to the Chamber of Deputies; in 1993, with the first elections under the new rules, women's seat share increased from 5% to 14%. Since Argentina renews half of the Chamber every two years, the quota's full effects were not realized until 1995, when women's seat share rose to 27%. Women's presence in the lower house has continued to grow, reaching 36% in the 2005 elections. The Ley de Cupos was applied to the Senate in 2001, following a reform of Senate electoral rules. In the 2001 elections, women's presence in the Senate jumped from 5.7% to 37.1% (Marx, Borner, and Caminotti Reference Marx, Borner and Caminotti2007, 81–83).

In this section, we explore the effects of quotas in Argentina using evidence from three data sources: bill introduction, legislative success, and interviews with legislators. This combination allows us to compare legislators’ descriptions and perceptions about their work (gained through interviews) with data that record their actions (bill introduction) and results (bills passed). This method yields a more complete picture than single-indicator studies, in that we begin to understand why (not just whether) sex-differentiated patterns of representation emerge.

To analyze patterns of bill introduction and legislative success since the adoption of the quota law, we use data archived by the Argentine Congress.Footnote 6 Our interview data come from semistructured interviews with 27 legislators (26 women and one male) from five different political parties; we interviewed legislators from the two major parties—the Partido Justicialista (PJ, Peronist party) and the Union Cívica Radical (UCR, Radical Party)—as well as the smaller parties. The majority of the interviews were conducted with deputies and senators serving in the 2003–5 and 2005–7 Congresses, although three were legislators at the subnational level and four were former legislators. Our interviews used open-ended questions to elicit legislators’ responses on the following: their policy priorities, their work, and their thoughts on quotas, representation, party politics, and congressional politics. Our goal was to randomly sample interviewees from the legislative directories, and approximately 30% of interview requests were granted; however, we acknowledge that a selection bias may have occurred, as those granting interviews likely held stronger opinions about women's representation than those refusing interviews. To accompany the legislator interviews, we also interviewed women's movement activists, Argentine researchers, legislative assistants, and federal bureaucrats (who were asked similar questions about quotas, representation, legislative priorities, and party politics). For the noncongressional interviewees, we initially contacted individuals known in the academic and activist communities for their work on women's rights; we then asked these noncongressional interviewees to recommend other colleagues.Footnote 7 Overall, we believe that the interviews offer invaluable insight into how mandates and labels are experienced by legislators, perceptions not available through quantitative indicators. We use these perceptions to complement our quantitative data.

Taken together, the evidence reveals that elected women are successfully gendering the legislative agenda but not successfully gendering legislative outcomes. First, legislators reported a perceived obligation to represent women's concerns. We locate the origins of this mandate effect in the 1991 quota campaign, where the alliance of advocates in civil and political society instilled among activist women a sense of togetherness and of debt. Second, and surprisingly, legislators also reported that Argentine political parties have implemented quotas by nominating “mujeres de” (literally, “women of [a man],” that is, wives or relatives of male party leaders). The quota law gendered the already-common practice of nepotism in Argentina, as reports emerged that political parties complied with the new law by replacing male candidates with a female relative (Piscopo Reference Piscopo2006). Although we cannot document the frequency of these substitutions, interviewees repeatedly remarked on this practice. Politicians’ preoccupation with mujeres de suggests that the problem is perceived to be real, even if its occurrence is less widespread than feared. As we discuss in the following, while interviewees agree that the mujeres de label exists, they disagree about its actual consequences.

Mandates

Consistent with our hypotheses in the previous section domestic mobilization around and political rhetoric about quotas generated a mandate effect in Argentina. First, the mobilization of women in both political and civil society instilled norms of cooperation and collaboration among female politicians and women's movement activists. Quota proponents lobbied male party leaders and members, and raised public awareness through media campaigns and street demonstrations. During the quota bill debate, female supporters filled the observation galleries, cheering for deputies who argued in favor of the quota and booing those who spoke against it.Footnote 8 The Network of Political Women was created, comprised of women from 15 political parties, and it organized sessions with women in both provincial and national legislatures (Archenti and Johnson Reference Archenti and Johnson2006; Lubertino Reference Lubertino2003). From 1991 to 1995, this network remained active in encouraging female party members to seek nominations, monitoring parties’ compliance with placement mandates, and shaming parties who shirked their obligations (Chama Reference Chama2001).

Second, many of the arguments employed by quota proponents focused on the need for women's voices in politics, as articulated in the slogan adopted by the Network of Political Women: “With few women in politics, it's the women who change. With many women in politics, politics changes” (Marx, Borner, and Caminotti Reference Marx, Borner and Caminotti2007, 61). During the debate in the Chamber of Deputies, some advocates did identify quotas as correctives for gender discrimination. Other advocates pointed to women's “difference,” arguing that women would bring distinct perspectives and issues to politics. Three deputies in particular used this consequentialist argument. Gabriela González Gass explained that while women's views have been historically “condemned to the private sphere,” women now find themselves able “to contribute to the construction of a new discourse[;] they can elaborate new policies, attend to the daily realities of the people, and produce a renovation in leadership” (cited in Perceval Reference Perceval2001, 108). Another, María Martín de Nardo, spoke of women's “nourishing presence” and their “distinct ways of seeing.” Likewise, Matilda Quarracino argued that “whether by culture, biology, or education, women are more sensitive to the real needs, daily and concrete, of the people” (cited in Perceval Reference Perceval2001, 111). Two female politicians present during the debate—Deputy Irma Roy and Senator and co-author of the Ley de Cupos Liliana Gurdulich—recalled the “enormous energy and sense of possibility that filled the chamber”; the women were, Gurdulich reflected, “initiating a moment of great change in Argentina.”Footnote 9 By appealing to women's difference and by proclaiming a moment of change, female quota proponents created a mandate for female legislators to be substantive representatives.

Interviews with female legislators reveal the strength of mandates. One deputy said that her obligation to represent women derives from women's collective struggles, beginning with the suffrage movement, so that she could occupy elected office. She added that “if it weren't for the quota law, I may not have been in the second spot on the list.”Footnote 10 Other interviewees made similar statements, attributing their election to quota campaigners’ opening of political spaces for women.Footnote 11 In describing her commitment to women's issues, one legislator referenced the arguments used by quota advocates during the campaign: Because the quota pioneers had emphasized equality, social justice (specifically the feminization of poverty), and women's historical marginalization, she feels that female legislators ought to address these issues.Footnote 12 While interviewees acknowledged that not all women perceive this connection, one activist (and former local officeholder) did explain that the quota campaign strengthened the relationship between the women's movement and political women, and that the Congress has expanded to include record numbers of activist women.Footnote 13 One such militant, a senator known for her feminist advocacy, likewise noted that the quota campaign taught political women and movement activists to work together. She explained that “we constructed a strategic solidarity, activism, and discourse,” adding that women's large-scale mobilization during the quota campaign created high expectations about the impact that women would have in the Congress.Footnote 14 In other words, the quota campaign generated mandates, now felt by many female politicians elected under quotas.

Among the female legislators interviewed, we found widespread agreement that the quota law facilitated the proliferation of women's themes on the legislative agenda. A female senator noted that “the arrival of thirty percent women meant that the Senate began to debate themes that hadn't been discussed before.”Footnote 15 Interviewees also pointed to concrete issues: A senator noted that the quota led to greater attention to “children and adolescence, penal laws, sexual assault laws, and laws on maternity leave and pregnancy,” and a deputy pointed to issues such as “sexual education, surgical methods of contraception [tubal ligation and vasectomy], emergency contraception, and others.”Footnote 16 Outside of the legislature, activist women also noted the agenda change in the Congress.Footnote 17 Congressional and noncongressional interviewees did stress, however, the difference between discussion and outcome: Several observed that while female legislators’ introduction of such topics signaled an important advance for Argentine women, agenda change did not automatically translate into policy change.Footnote 18 These comments highlight the importance of recognizing substantive representation as process as well as outcome: A Socialist legislator stressed that given the previous and long-standing marginalization of women's issues from Argentine politics, having contraception or abortion discussed at all signified a step forward.Footnote 19 Likewise, her colleague explained that “there are certain themes that, if it weren't for the quota law, would not have entered public debate with such richness.”Footnote 20

Bill introduction data supports politicians’ and observers’ perceptions that female legislators are more likely to put women's issues on the legislative agenda. We analyzed patterns of bill introduction in four areas that firmly fall within the classification of women's issues: promoting gender quotas, penalizing sexual harassment, combating violence against women, and protecting and expanding reproductive health and rights. Introducing these women's rights bills is consistent with substantive representation as process, wherein legislators take action on behalf of some or many women constituents.

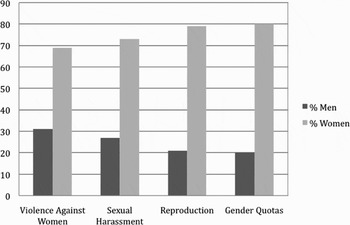

In examining all bills introduced in these areas over a 19-year period (1989–2007), we found that the vast majority were introduced by women (see Figure 1). Women authored 79% of the bills on gender quotas, a category that includes the application of quotas to other bodies, such as the judiciary or the executive, as well as bills to increase the existing congressional quota from 30% to 50%. In the area of reproductive rights, women introduced 80% of the bills to legalize abortion and to expand access to contraception, and to improve reproductive health through education and access. In the area of violence against women, a category that includes all bills to enhance women's protection from violence, female legislators sponsored 69% of all bills. Women also authored 73% of bills aimed at combating sexual harassment.

Figure 1. Percent of bills introduced by sex, 1989–2007. (Source: Authors’ calculations, compiled from data retrieved from the Dirección de Información Parlamentaria [Office of Parliamentary Information]. The database is maintained by the Argentine Chamber of Deputies for both the lower house and the Senate (http://www.hcdn.gov.ar/dependencias/dip/qryproy2.html.)

While much of the existing literature on women and politics finds a positive correlation between gender activism and leftist parties, this finding does not appear in Argentina, where parties are not organized around a left–right cleavage (Coppedge Reference Coppedge1998). Indeed, the two traditional parties, the Peronists and the Radicals, contain progressive and conservative segments. Our data show that in the Argentine Congress, partisan identification does not determine legislators’ actions. Peronist legislators, male and female, introduced the largest proportion of bills across the four policy areas (see Table 1). This dominance does not mean that Peronist legislators care more about women's issues; rather, it reflects the Peronists’ greater proportion of seats in the Argentine Congress in the period under study. Peronists introduced between 45% and 56% of bills in the four areas; legislators from the Radical Party (the main opposition) introduced the second largest proportion of bills, followed by legislators from the smaller parties. In the category of reproductive rights, the difference between Peronists and Radicals decreased, with the parties introducing 31% and 30% of the bills, respectively. The only noticeable legislative concentration among the smaller parties also appears in this area, with the Socialists introducing 11% of the bills from 1989 to 2007 (compared to 0% and 2% in the other bill categories). Socialist legislators perhaps care more about reproductive rights than other women's issues, yet they are not monopolizing the agenda. Legislators from all parties act in this area. Overall, these proportions show that gender activism is not concentrated within one party.

Table 1. Percentage and number of women's rights bills introduced by party, 1989–2007

Note: For sexual assault, gender quotas, and violence against women, total bills are lower than reported elsewhere in the article due to missing observations for legislators’ party affiliation.

Source: Authors’ calculations, compiled from data retrieved from the Dirección de Información Parlamentaria [Office of Parliamentary Information] (http://www.hcdn.gov.ar/dependencias/dip/qryproy2.html).

The data also show that female legislators are introducing the vast majority of their parties’ contributions to each category. Female legislators introduced 79% of gender quota bills; female Peronists introduced 77% of the Peronist-initiated quota bills, and female Radicals introduced 78% of the Radical Party–initiated quota bills. Likewise, women introduced 69% of the total violence-against-women bills; female Peronists introduced 74% of their party's share, and female Radicals introduced 63% of their party's share. Overall, the proportion of women within each party introducing women's interests bills is fairly consistent with the proportion of total women introducing bills. In all cases, female party members are more likely to introduce women's rights bills than are their male colleagues, regardless of party membership.

Even more important, the frequency of women's initiatives has risen with the continued application of quotas, particularly once quotas began to apply to Senate elections (see Figure 2). Adding all the women's rights bills, we divided the years into three periods: 1989–94, 1995–2000, and 2001–7. These periods correspond to when quotas achieved numerical changes: the jumps in 1995 (when the quota applied to the whole Chamber) and in 2001 (when the quota applied to the Senate). Increases in bill introduction are consistent with this periodization. From 1989 to 1994, when women's presence in the lower chamber grew from 5% to 14%, an average of 7.2 women's interests bills were introduced per year. From 1995 to 2000, when women's presence in the lower house jumped to 27.2% and averaged 2.8% in the Senate, an average of 11.3 bills were introduced per year. Between 2001 and 2007, however, when women's presence in both houses jumped to over 30%, an average of 30.3 bills were introduced per year, a 268% increase when compared to 1995–2000. Even more striking, in the category of violence against women, bill introduction increased over 500% from 1995–2000 to 2001–7, moving from an average of 2.8 bills a year to 12.4 bills a year. Bill introduction in the categories of sexual harassment and reproductive rights increased threefold between these two periods, and bill introduction in gender quotas increased twofold. The data also reveal substantial variation in terms of bill authorship, suggesting that the ideological commitments of several feminist legislators are not skewing the yearly counts.Footnote 21

Figure 2. Bill introduction by year. (Source: Authors’ calculations, compiled from data retrieved from the Dirección de Información Parlamentaria [Office of Parliamentary Information]. http://www.hcdn.gov.ar/dependencias/dip/qryproy2.html).

The final conclusion we draw from our data concerns men's legislative activity on women's rights initiatives. Our data show that although male legislators introduced a slightly larger number of bills in the last period when compared to the first, their legislative activity comprises a diminishing proportion of women's rights initiatives (see Figure 3). In the first period, where women's presence was scarce, men introduced over half of the women's rights bills. In the last period, where women hold more than 30% of the seats, male legislators introduced only 21% of the bills in these four areas. Thus, increasing the descriptive representation of women has not had strong diffusion effects on the actions of male legislators; if anything, female legislators have become more responsible for introducing women's rights bills. This finding lends preliminary support to Leslie Schwindt-Bayer's prediction that women's entrance may threaten male dominance: Male leaders may respond to women's presence by establishing a gendered division of labor, wherein female legislators are encouraged (or even pressured) to introduce the less prestigious women's issues bills (2006, 573).

Figure 3. Patterns of bill introduction by sex and year. (Source: Authors’ calculations, compiled from data retrieved from the Dirección de Información Parlamentaria [Office of Parliamentary Information]. http://www.hcdn.gov.ar/dependencias/dip/qryproy2.html).

The bill introduction data overall provide evidence that agenda changes have occurred in Argentina since 1991 and that these changes are not dependent on the activism of women in any particular party. A pro-women's rights legislative agenda has been established by women working individually or cooperatively in small groups; contrary to the expectations of critical mass theorists, female legislators in the Argentine Congress have not united to form a bancada femenina (women's caucus). One interviewee distanced herself from any mandate, stating that women need neither act as women nor in concert with other women; they must act as politicians first.Footnote 22 As further evidence that not all legislators perceive mandates, Nélida Archenti and Niki Johnson (2006) found that between 1994 and 2003, only half of female legislators in Argentina introduced at least one bill with gender content. Shared features (biological sex) guarantee neither shared beliefs nor automatic allegiances among women. Nonetheless, our bill introduction data and interview data provide evidence that enough female legislators perceive mandates, and take action to represent women, to have changed the legislative agenda.

Our interviews also reveal other ways that female legislators — as individuals or in small groups—undertake women's substantive representation as process. One senator discussed the impact that women's presence had on a committee to reform Senate procedures. The committee, composed of five women and one man, improved transparency of Senate activities by opening all meetings to the public. In addition, the female members won a reform that moved all Senate sessions from 6 p.m. to 3 p.m. This latter change addressed a long-standing complaint by political women that political hours, especially evening meetings, reflect masculine norms and preferences.Footnote 23 Additional actions that reflect substantive representation as a process include female legislators’ efforts to consult and communicate with women organized in civil society. One legislator holds weekly office hours wherein female community leaders from Argentina's las villas miserias (shantytowns) meet with her to discuss ongoing problems of sanitation, health care, and child nutrition.Footnote 24 Other legislators likewise noted their efforts to maintain open communications with women's groups, especially those working on domestic violence and reproductive rights. These efforts include keeping organizations abreast of legislative developments (such as committee hearings) and also participating in roundtables and other events organized by women's groups.Footnote 25

The preceding discussion shows how quotas, and the mandates created through the campaign, have positively contributed to women's substantive representation as process in Argentina. In instances where legislative success is achieved, substantive representation as process and substantive representation as outcome occur together. Interviewees highlighted three important women's rights bills passed since the implementation of the quota law in 1991: the Labor Union Quota in 2002, which applies a 30% quota to leadership posts in labor unions; the Sexual Health Law in 2001, which created a national health program for sexual health education and contraception availability; and the Surgical Contraception Law in 2006, which expanded the 2001 Sexual Health Law by legalizing surgical contraceptive methods and making the procedures (including vasectomies) available in public hospitals.Footnote 26

These successes notwithstanding, we argue that three laws constitute neither a dramatic nor wholesale change to policy outcomes in Argentina. The majority of women's rights bills actually do not succeed. Between 1989 and 2007, there were 67 bills introduced to apply gender quotas beyond congressional candidacies or to increase the existing quota beyond 30%; only the 2002 Labor Union Quota succeeded. Of the 93 bills introduced dealing with reproductive rights, only two succeeded (the Sexual Health Law and the Surgical Contraception Law). Although the Argentine legislative process is such that bill failure is common, the success rates for approving women's rights bills is lower than average. Of the women's rights bills analyzed, the three successes constitute a 1.3% success rate between 1999 and 2006. An analysis conducted by an Argentine nongovernmental organization found much higher overall success rates: From 1999 to 2006, 3.73% of all bills introduced in the Chamber of Deputies passed both houses, and 2.15% of all bills introduced in the Senate also succeeded (Barón et al. Reference Barón2007). Women's issues bills therefore fail more often in the Senate, and over twice as frequently in both chambers.Footnote 27 Given that female legislators introduce most women's issues bills, the data indicate that women change policy outcomes in women's issue areas at rates proportionally below the norm in the Argentine Congress.

Legislative success is dependent on institutional rules; formal and informal norms can limit female legislators’ ability to move from bill introduction to bill passage. Formal norms refer to procedures and business practices understood and followed by all legislators. Many interviewees pointed to party discipline as a critical factor reducing the success of women's rights initiatives. While not ideologically organized, Argentine parties are known for being highly disciplined (Jones Reference Jones, Morgenstern and Nacife2002), thus reducing legislators’ opportunities to build cross-partisan consensus on women's rights bills.

Interviewees also cited party leaders’ agenda control and executive dominance as another obstacle, especially for legislators outside of the majority bloc. Women often lack the influence necessary to force a committee or plenary discussion on their women's rights initiatives. One senator explained that “it's totally up to the committee chair [whether a bill advances], and even if there's political will there, someone higher up—the president, for example—will send signals to committee chairs about whether a bill should move or not.”Footnote 28 Another legislator explained that legislative success is contingent upon a range of factors, including the content of the bill, its author, and whether its main proponent is from the majority or minority party.Footnote 29 Ultimately, female-focused legislative initiatives usually die in committees (rather than failing in floor votes); initiatives will not reach the floor without leaders’ support. Several interviewees further noted that legislative success also requires that the president endorse, or at the very least not oppose, a particular policy direction. Our interviewees’ remarks are consistent with existing scholarship on the Argentine Congress. Mark Jones (Reference Jones, Morgenstern and Nacife2002, 182) notes that party presidents perform important gatekeeping functions: leaders can block their colleagues’ legislative initiatives from floor discussions and determine which legislators participate in parliamentary debates.

Formal norms are relatively gender neutral, in that they affect both male and female legislators. Informal norms, by contrast, affect women disproportionately and limit their maneuverability. One legislator emphasized the schedule for parliamentary work: “Legislators work from 9 a.m. to 10 p.m., and at 10 p.m. women go home or phone home while the men begin their planning and strategy sessions. I think they choose that time because they know we won't stay.”Footnote 30 Other female politicians discussed their discomfort with attending nighttime meetings, which are often held off-site in bars. Another noted that political schedules create a double standard for women: If they skip the meeting, they are treated as uncommitted to their work and thus lose professional respect. If they attend, however, they are considered more sexually freewheeling, and thus lose personal respect.Footnote 31 Other women cited difficulties in having their opinions received fairly during discussions and debates. As one young legislator noted, “A man gives his opinion and everyone listens. A woman gives her opinion and she needs boxes of documents and experts waiting outside to back her up.”Footnote 32 Likewise, a legislator's policy assistant noted, “Men just talk even if they know nothing; the women only feel comfortable speaking if they know the topic.”Footnote 33 These comments illustrate how the Congress's informal norms are functionally adapted to male beliefs about women. In practices ranging from bargaining arrangements to exchanging information, female legislators perceive that they are disadvantaged: They are simultaneously subjected to greater criticism and higher standards.

Labels

Essentially, women's entrance into Argentine politics has not precipitated women's greater empowerment (Marx, Borner, and Caminotti Reference Marx, Borner and Caminotti2007). A common sentiment expressed in interviews is that “the quota increased the number of women [in the Congress]; it hasn't increased their power.”Footnote 34 Indeed, many respondents cautioned us against conflating women's presence with women's power—where power means female legislators’ ability to transform policy outcomes. To some extent, women's lack of power results from the formal and informal norms that entrench gender bias. Numerous interviewees also credit the mujeres de phenomenon with reducing women's power: When asked about the quota's impact, women's roles in the Congress, and legislators’ gender consciousness, interviewees spontaneously began to discuss the mujeres de. It is important to point out the term mujeres de was offered by Argentines and not selected by the researchers.

According to interview respondents, an unanticipated effect of the quota was that party leaders met (or resisted) the quota requirements by nominating female relatives or wives to fill in the spots now unavailable to male candidates (Piscopo Reference Piscopo2006). One legislator explained that “because the law obliges the parties to nominate women, the men seek women that they know they can give orders to[;] for example, they seek mujeres de [women of].”Footnote 35 A male party leader admitted that his wife was placed in the second list position (after himself), and commented that “we have complied with the quota through our marriage.”Footnote 36 A number of interviewees were highly critical of these substitutions. One deputy explained that “the women keep the seats warm until the men come back” and that “the women pick up the phone and ask the man, how should I vote, and so they vote.”Footnote 37 Another described the mujeres de as “silent” women who never spoke or acted until instructed by party bosses.Footnote 38 Other legislators implied that mujeres de have lower levels of gender consciousness, thereby mitigating the impact of the gender quota law on women's substantive representation. Overall, these interviewees contribute to and reinforce the label effect, identifying “quota women” as obedient loyalists.

Other respondents expressed frustration with the negative stereotypes resulting from the mujeres de phenomenon. First, some interviewees noted that the problem is probably exaggerated by those who resent the quota. As one legislator explained, while party leaders do sometimes nominate female relatives, the presumption that all nominees are mujeres de is inaccurate; the allegations are most frequently made by quota critics, including some feminists who oppose the quota.Footnote 39 Another legislator cautioned that the phenomenon has contradictory effects: It allows for the inclusion of women onto party lists while simultaneously generating a stereotype that excludes women from the circles of power. This legislator further explained that even when female nominees are related to male party leaders, some of these women do have their own political base. Likewise, a male politician noted the frequency of political couples in Argentina, for many activist men and women meet through university-sponsored party militancy activities.Footnote 40 These respondents offered a more nuanced portrait, for according to an Argentine researcher, “the mujeres de phenomenon is a preconception. There is no definitive quantitative data.”Footnote 41

While nepotism, or the practice of party elites’ relatives receiving nominations, is widespread in Argentina, female politicians appear to sustain greater criticisms for being mujeres de than male politicians sustain for being hombres de (“men of”). Charges of nepotism became particularly acute during the last presidential campaign, when the wife of outgoing President Néstor Kirchner became the leading candidate for his replacement. The Argentine media dwelled heavily on the fact that Cristina Fernández de Kirchner was the First Lady, rather than the fact that she was a two-time national senator who had entered electoral politics prior to her husband's election as president.Footnote 42 Beyond the high-profile case of Fernández de Kirchner, the 2007 elections overall showed numerous instances of nepotism. A national newspaper reported 23 cases of national and local candidates (male and female) having kinship ties to well-known political figures; just over half were mujeres de and just under half were hombres de.Footnote 43 Yet, as one senator explained, women are more vulnerable to attacks in the press.Footnote 44

Label effects also disproportionately affect young women and political newcomers. One interviewee shared her story: “I had been a community organizer in the barrio [neighborhood] for years. The party boss nominated me because of my work as a party militant. Yet the minute I received the nomination they [other party members] said I had slept with him.”Footnote 45 She also noted that she could not disprove the rumors of the affair, despite her husband's own participation in and support for her campaign. Given these difficulties, two interviewees expressed concerns that qualified women may eschew electoral politics altogether, in order to avoid such negative labels.Footnote 46

Interviewees also referenced another variant of the label effect, a demeaning characterization given to those legislators most active on gender issues. One deputy noted that parity advocates in her party, those who push leaders to incorporate more women into committees and delegations, are derided as “las locas del 50–50 [the 50–50 crazies].”Footnote 47 Other respondents echoed similar claims about the lack of respect for women who promote feminist issues; one diputada noted that women with strong opinions were always called locas.Footnote 48 These labels can undermine substantive representation as process. Some women become unwilling to associate themselves with feminist initiatives for fear of being marginalized as a result. As one deputy noted, some women believe that “it limits them to dedicate themselves to women's rights themes, so they prefer a public profile that is more expansive.”Footnote 49 If there are fewer women willing to associate themselves with feminist initiatives, then those legislators who do engage in substantive representation as process may encounter greater difficulties finding allies, thereby making substantive representation as outcome even less likely.

In sum, the bill introduction data, legislative success data, and interview data all support our hypothesis that legislated candidate gender quotas can generate mandate effects under certain conditions. Even those not perceiving a mandate effect recognized that quotas have transformed the legislative agenda. Despite women's success in transforming the legislative agenda, they have not succeeded in transforming legislative outcomes. The main factors inhibiting legislative success are institutional, namely, party leaders’ and executive control of the legislative process and informal norms that entrench gender bias. As a complicating factor, the quota law has also created perceptions about mujeres de as legislators who are less serious about policymaking and less likely to be committed to women's rights. While the data cannot confirm that label effects undermine substantive representation as outcome, many interviewees believe that negative stereotypes about “quota women” reduce women's ability to build solidarities and to accumulate power and influence.

CONCLUSIONS AND DIRECTIONS FOR FUTURE RESEARCH

We have used the Argentine case to explore women's substantive representation. Our main contribution to the theoretical literature is clarifying the concept of substantive representation by analytically separating two aspects that are often conflated: substantive representation as process, wherein legislators change legislative agendas, and substantive representation as outcome, wherein women's rights laws are adopted. As the Argentine case demonstrates, these two aspects of substantive representation do not always occur together. The distinction also allows researchers to determine more precisely the factors that shape both aspects of substantive representation. We show that where quota campaigns generate mandates, improved substantive representation as process is likely. Yet gender quotas cannot change the institutional rules and norms that govern the legislative process, meaning that quotas cannot guarantee improvements in substantive representation as outcome. Legislatures may be unequal playing fields for women, who enter as newcomers and who face higher barriers to empowerment.

Our research provides a number of directions for future research on gender quotas and substantive representation. First, researchers could explore mandate effects in comparative contexts to determine whether the factors we have identified (domestic mobilization and consequentialist arguments) are necessary for mandates to emerge. Second, researchers could test the durability of mandates, exploring whether the increased legislative activism on women's rights is sustained over time. Finally, our findings point to the need for future research into label effects. We showed that many political actors perceive labels to matter, and future studies might investigate whether labels do impact women's legislative roles. Researchers might conduct surveys that explore perceptions of “quota women,” compare rates of legislative success between men and women, or compare male and female legislators’ political backgrounds to determine the accuracy of claims about the low qualifications of “quota women.” Research along these lines would shed even more light on the ways that legislated gender quotas affect women's ability to undertake substantive representation.