A large body of research on democratic attitudes reveals important variation across individuals and across countries in how citizens understand democracy (e.g., Canache, Mondak, and Seligson Reference Canache, Mondak and Seligson2001; Chu et al. Reference Chu, Diamond, Nathan and Shin2008; Crow Reference Crow2010; Schedler and Sarsfield Reference Schedler and Sarsfield2007). This article offers the first systematic exploration of whether men and women harbor different conceptions of democracy. Further, we explore how those differences relate to their overall support for and satisfaction with democracy.

Drawing on Round 6 of the European Social Survey (ESS) (2012), our analyses show that women tend to consider less important for democracy those aspects that privilege male resources and power, such as representative institutions, political parties, and the media. Instead, women assign more importance to those aspects of democracy that are less prone to reproduce gender inequalities, such as those related to direct participation (i.e., referenda), public justification of government decisions, and the protection of social rights. The results also indicate that the gender gap in conceptions of democracy tends to be more pronounced in countries with more robust democratic systems, such as Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, Belgium, and France, and that it is not associated with similar disparities in overall support for democracy between men and women. The differences between men and women are relatively small, although they are comparable in magnitude to the effects of other individual characteristics such as education, satisfaction with the economy, and institutional trust.

By providing initial results for an understudied topic in gendered politics, this article also contributes to the broader literature on democratic attitudes. Building on recent developments in democratic theory (Warren Reference Warren2017), we propose that citizens’ support for democracy derives from their experiences with specific institutions that empower them to participate in political processes, not from well-formed ideas about abstract “models of democracy” (e.g., liberal, deliberative, participatory, social-democratic, etc.) (Canache Reference Canache2012; Ferrín and Kriesi Reference Ferrín and Kriesi2016; Schedler and Sarsfield Reference Schedler and Sarsfield2007). High-quality democracies offer a wider array of institutions for the exercise of political practices. In those settings, citizens from different social groups are more likely to find institutions that politically empower them despite broader asymmetries present in society and, thus, develop higher levels of support for and satisfaction with democracy.

CURRENT RESEARCH ON DEMOCRATIC ATTITUDES AND GENDER

As cross-national comparisons proliferated in the context of the Third Wave of democratization, early research on democratic attitudes encountered two important challenges (Bratton and Mattes Reference Bratton and Mattes2001; Bratton, Mattes, and Gyimah-Boadi Reference Bratton, Mattes and Gyimah-Boadi2005; Carlin Reference Carlin2006, Reference Carlin2011; Carlin and Singer Reference Carlin and Singer2011; Chu et al. Reference Chu, Diamond, Nathan and Shin2008; Dalton, Sin, and Jou Reference Dalton, Sin and Jou2007). First, democracy is an essentially contested and multidimensional concept that scholars and citizens associate with many different things (Collier, LaPorte, and Seawright Reference Collier, LaPorte and Seawright2012; Ferrín and Kriesi Reference Ferrín and Kriesi2016; Ulbricht Reference Ulbricht2018). What exactly people have in mind when they claim to support democracy is difficult to know: a set of political institutions and procedures such as free and fair elections or direct popular participation; certain normative values such as tolerance, individual freedom, or social justice; or concrete social outcomes such as economic growth, material redistribution, or law and order (Dalton, Sin, and Jou Reference Dalton, Sin and Jou2007, 144). Second, the meaning of democracy not only varies across citizens but also across countries and cultures, which questions the validity of overly general measurement instruments (Ariely and Davidov Reference Ariely and Davidov2011; Canache, Mondak, and Seligson Reference Canache, Mondak and Seligson2001; Schedler and Sarsfield Reference Schedler and Sarsfield2007).

Scholars have addressed these challenges by moving down the ladder of generality to measure citizens’ support for specific institutions, ideals, or outcomes that are commonly associated with democracy. They have done this either by asking survey respondents to provide their own definitions of democracy in response to open-ended questions or to scale generic attributes of democracy from a closed list (e.g., Canache Reference Canache2012; Carlin and Singer Reference Carlin and Singer2011; Ferrin and Kriesi Reference Ferrín and Kriesi2016; Schedler and Sarsfield Reference Schedler and Sarsfield2007). The responses are then used to identify the extent to which citizens intuitively support alternative “models of democracy” (Canache Reference Canache2012; Ferrín and Kriesi Reference Ferrín and Kriesi2016; Schedler and Sarsfield Reference Schedler and Sarsfield2007).

Despite this extensive literature, to our knowledge, there has been no systematic effort to examine differences between men and women's understandings of democracy across multiple national contexts. The gap in the literature is surprising given existing research on gender inequalities in political representation (Caul Reference Caul2001; Karp and Banducci Reference Karp and Banducci2008; Koch Reference Koch1997; Krook Reference Krook2009; Norris Reference Norris2004; Paxton Reference Paxton1997; Rosen Reference Rosen2017; Ruedin Reference Ruedin2012; Sommer Reference Sommer2013), policy preferences (Inglehart and Norris Reference Inglehart and Norris2000; Kaufmann and Petrocik Reference Kaufmann and Petrocik1999; Kellstedt, Peterson, and Ramirez Reference Kellstedt, Peterson and Ramirez2010; Schlesinger and Heldman Reference Schlesinger and Heldman2001; Hansen Reference Hansen2019), political engagement, participation and knowledge (Beauregard Reference Beauregard2018; Fraile Reference Fraile2014; Fraile and Gomez Reference Fraile and Gomez2017; Wolak Reference Wolak2015), and satisfaction with democracy (Anderson and Guillory Reference Anderson and Guillory1997).

At the same time, research on democratic attitudes indicates that differences between men and women in overall support for democracy disappear as the quality of democracy improves and citizens from all social groups internalize democratic norms and values (e.g., Andersen Reference Andersen2012; Carnaghan and Bahry Reference Carnaghan and Bahry1990; Gibson, Duch, and Tedin Reference Gibson, Duch and Tedin1992; Konte and Klasen Reference Konte and Klasen2016; Logan and Bratton Reference Logan and Bratton2006; Waldron-Moore Reference Waldron-Moore1999; Walker and Kehoe Reference Walker and Kehoe2013). Indeed, the most recent studies on democratic attitudes in established democracies find no statistically significant differences in support for democracy between men and women (Quaranta Reference Quaranta2018, 872; Ulbricht Reference Ulbricht2018, 30).

A PROBLEM-BASED APPROACH TO THE STUDY OF DEMOCRATIC ATTITUDES

Why do we observe similar levels of support for democracy even if existing democratic institutions disproportionately benefit men and disadvantage women? To answer this question, it is necessary to analyze what it is about democracy that people support. We argue that citizens hold differentiated views about which aspects of democratic politics are most important based on how they benefit from them. Therefore, we expect differences in overall support for democracy between social groups to be smaller where their members have access to a wider array of institutions that empower them despite larger structural inequalities.

Our argument builds on the recent “systemic turn” in democratic theory, especially Mark Warren's “problem-based approach” to democracy (Warren Reference Warren2017). Rather than starting from a practice or institution and then building a model of democracy around it, Warren proposes to begin by asking two questions: “What problems does a political system need to solve if it is to function democratically?” And “what are the strengths and weaknesses of generic political practices as ways and means of addressing these problems” (Reference Warren2017, 39)?

In response to the first of these questions, Warren argues that to count as democratic, political systems need to perform three broad functions (Reference Warren2017, 44–45). First, democracies empower their citizens to participate in political processes (empowered inclusion). Second, democracies form collective agendas “that reflect the interests, perspectives, and values of those included” (collective agenda and will formation). Third, democracies make collective decisions to provide common goods for themselves (collective decision making).

Democracies perform these three functions through a wide array of institutions (e.g., elections, courts, parliaments, referenda, political parties, and the media) that provide citizens with opportunities to exercise key political practices: recognizing, resisting, representing, deliberating, voting, joining, and exiting (Warren Reference Warren2017, 47–50). Through the exercise of these practices, citizens influence political processes, form collective wills, and act collectively as a people. No single institution, no matter how essential, is sufficient to organize all of these practices or to perform any of the broad democratic functions on its own, let alone all three of them. Moreover, every institution interacts with the various power asymmetries of society in ways that privilege certain actors and interests over others. These political inequalities in specific institutions are not a problem for democracy as long as the overall system of institutional complementarities and redundancies cancels out their negative impacts on empowered inclusion, collective agenda and will formation, and collective decision making.

In our view, this understanding of democracy approximates the way citizens intuitively think about and develop normative attachments to democratic politics. Rather than committing to abstract ideals or models of democracy, citizens value concrete institutions and practices that empower them to exercise democratic practices. Because individuals have access to different resources and are affected in different ways by structural inequalities present in society, specific institutions are likely to empower some citizens more than others. Consequently, we broadly expect that members of different social groups emphasize the importance of those parts of the democratic system that effectively empower them, and see those institutions that privilege the influence of other actors as less important for democracy. Based on this argument, we have derived a subsequent set of hypotheses about which institutions are more likely to be deemed important for democracy by women and by men.

First, legislatures and other representative institutions have historically served as a gatekeeping device to limit the political participation of women. Even today, representative institutions continue to be dominated by men (Norris Reference Norris2004; Paxton Reference Paxton1997; Ruedin Reference Ruedin2012), to reward typically male forms of political socialization (Dolan Reference Dolan2005; Galais, Öhberg, and Coller Reference Galais, Öhberg and Coller2016; Lawless and Fox Reference Lawless and Fox2010), and to reproduce power asymmetries from other social spheres, from the gendered division of labor in parliamentary committees (Bäck, Debus, and Müller Reference Bäck, Debus and Müller2014; Baekgaard and Kjaer Reference Baekgaard and Kjaer2012) to gendered differences in access to campaign finance (Burrell Reference Burrell1985; Crespin and Deitz Reference Crespin and Deitz2010; Kitchens and Swers Reference Kitchens and Swers2016). Thus, we posit our first hypothesis:

H 1:

Women place lower importance than men on elections and legislatures.

Second, intermediary bodies that structure political competition (e.g., political parties and interest groups) also tend to be male dominated and are more likely to favor resources, interests, discourses, experiences, behavior, and world views typically associated with or controlled by men (Dolan Reference Dolan2014, Reference Dolan2018; Dolan and Hansen Reference Dolan and Hansen2018; Koenig et al. Reference Koenig, Eagly, Mitchell and Ristikari2011; Sanbonmatsu and Dolan Reference Sanbonmatsu and Dolan2009). Indeed, women are less likely than men to join political associations and parties and to actively participate in politics (Karp and Banducci Reference Karp and Banducci2008; Kittilson and Schwindt-Bayer Reference Kittilson and Schwindt-Bayer2010; Koch Reference Koch1997). These factors lead to our second hypothesis:

H 2:

Women see the functions of political parties as less important for democracy than men.

Conversely, direct participation in political decision making (e.g., through voting in referendums) circumvents the gendered asymmetries that characterize intermediary bodies. Although previous research has shown that direct democracy can hurt ethnic and racial minorities (Hajnal, Gerber and Louch Reference Hajnal, Gerber and Louch2002), women are less vulnerable to majority tyranny because in most normal circumstances they represent at least half of the electorate. Indeed, in some recent studies, women have tended to be more supportive of referendums than men in European countries (Bengtsson and Mattila Reference Bengtsson and Mattila2009, 1042; Leininger Reference Leininger2015, 30). The support may exist for various reasons. First, women may find that referendums are more likely to bring outcomes that are closer to their policy preferences than representative institutions. The enthusiasm around the 2018 referendum for abortion rights in Ireland illustrates this point nicely. Second, women may deem referendums a more important aspect of democracy because they derive other benefits from the process of direct participation, even if their preferred policies do not win, such as higher political engagement, greater political knowledge, or a heightened sense of political efficacy (Kim 2019). Therefore, we have formulated our third hypothesis:

H 3:

Women assign more importance to institutions that facilitate direct participation in political decision making than men.

Similarly, questions of legal and economic recognition have been at the core of feminist movements and remain today among the most important women's issues in the political agenda: abortion rights, protections from sexual harassment, labor market discrimination, equal pay, etc. (Mansbridge Reference Mansbridge1986; Pateman Reference Pateman1988; Phillips Reference Phillips1991, Reference Phillips1998). These social issues underpin our fourth hypothesis:

H 4:

Women see those institutions devoted to the equal protection of civil, political, and social rights as more important aspects of democracy than men.

Finally, we expect to find a more complex picture in the importance that men and women assign to institutions centered around deliberative processes, depending on whether they focused on “interpersonal” or “intrapersonal” deliberation (Goodin Reference Goodin2003; Goodin and Niemeyer Reference Goodin and Niemeyer2003). On one hand, critics of deliberative democracy have pointed out the various ways in which gender inequalities make men more likely to dominate and benefit from interpersonal deliberation (e.g., Karpowitz and Mendelberg Reference Karpowitz and Mendelberg2014; Karpowitz, Mendelberg, and Shaker Reference Karpowitz, Mendelberg and Shaker2012; Mendelberg, Karpowitz, and Oliphant Reference Mendelberg, Karpowitz and Baxter Oliphant2014). Such power asymmetries are present in both the everyday talk of the private sphere and in the political discourse of the public sphere (Beauvais Reference Beauvais2019).

H 5:

Women are less likely than men to see public debate as important for democracy.

On the other hand, one of the normative strengths of deliberation comes from the kind of accountability that public justification of political decisions makes possible. Public justification of political decisions allows voters to engage in processes of intrapersonal deliberation to provide (or withdraw) their reasoned support to those decisions, and in that regard is at the core of any meaningful ideal of self-government.

H 6:

Because intrapersonal deliberation is less exposed to structural inequalities, women are more likely than men to see institutions of public justification as important features of democracy.

How do these differentiated views about the importance of specific institutions affect overall levels of support for democracy? High-quality democracies are those in which the institutional system as a whole performs the core functions of empowered inclusion, collective opinion and will formation, and collective decision making. Thus, high-quality democracies offer multiple opportunities for members of different social groups to exercise various political practices across the different parts of the institutional system. As a result, people develop more differentiated views about which institutions are more important for democracy.

H 7:

Differences in the institutions that men and women consider more important are larger in countries with higher levels of democracy.

Nevertheless, an additional hypothesis follows:

H 8:

Precisely because both men and women can find institutions that politically empower them despite other structural inequalities present in society, equally high levels of support for democracy exist in both groups in high-quality democracies.

EMPIRICAL STRATEGY

Data

To empirically examine these hypotheses, we relied on Round 6 of the ESS, which explored political attitudes across 29 countries (European Social Survey 2012).Footnote 1 The ESS is an ongoing study measuring sociodemographics and attitudes of respondents in European countries since 2002. These surveys represent some of the largest collections of individual-level data related to European political attitudes currently available. Round 6 was fielded in 2012 and included a unique module that explored how citizens understand the concept of democracy, and how they assess specific aspects of democracy in their country.

In the analyses that follow, the main dependent variables of interest are those that measure the importance of each democratic institution for respondents. We analyzed 13 characteristics that respondents rated on a scale from 0 to 10, with 0 being “not at all important” and 10 being “extremely important.” Each variable has been rescaled to run from −5 to 5 for comparability.Footnote 2 The 13 characteristics used in this investigation are represented in the following questionnaire:

Prompt: Using this card, please tell me how important you think each of the following is for a democracy, where 0 is not at all important and 10 is extremely important. How important do you think it is for a democracy that…

1. National elections are free and fair?

2. Different political parties offer clear alternatives to one another?

3. Opposition parties are free to criticize the government?

4. That voters discuss politics with people they know before deciding how to vote?

5. That citizens have the final say on the most important political issues by voting on them directly in referendums?

6. That the media are free to criticize the government?

7. That the media provide citizens with reliable information to judge the government?

8. That the rights of minority groups are protected?

9. That the courts treat everyone the same?

10. That the government protects all citizens against poverty?

11. That the government takes measures to reduce differences in income levels?

12. That governing parties are punished in elections when they have done a bad job?

13. That the government explains its decisions to voters?

As control variables, all the multivariate models included age, education, income, employment status, union membership, and whether the respondent was born in another country. We also included three additional variables to control for other attitudinal factors that could be correlated with both gender and conceptions of democracy: (a) political ideology, which also works as a proxy for party identification in the pooled models; (b) satisfaction with the economy; and (c) institutional distrust. All continuous independent variables were scaled to have a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one to facilitate the interpretation of results.Footnote 3

METHODOLOGY

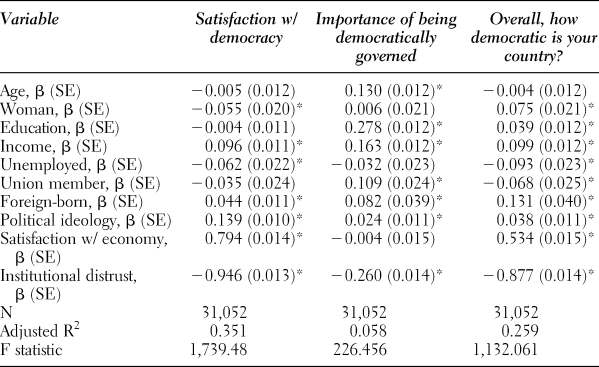

To fully investigate whether a gender gap in attitudes toward democracy exists, the empirical analyses proceed systematically in four parts. In the first part, the common general survey questions are used to explore whether a gender gap exists in attitudes toward democracy. The general survey questions deal with three democratic attitudes: (a) support for democracy: “How important is it for you to live in a democratically governed country?” (b) satisfaction with democracy: “How satisfied are you with the way democracy works in your country?” and (c) evaluation of democracy: “How democratic is your country overall?” All three evaluations were measured on a −5 to 5 scale, where 5 indicates the most positive evaluation. The three linear-regression multivariate models predicting these three indicators were estimated using country-level fixed effects models to account for systematic differences between the 29 countries, and they included poststratification survey weights. The basic model equation is

$$\eqalign{ &General\; Democratic\; Evaluation_i \cr &\quad= a_i + {B}_{1}Woman_{i} + {B}_2Age_i + {B}_3Education_i + {B}_4Income_i \cr &\quad+ {B}_5Unemployed_i + {B}_6Union\; Member_i \cr &\quad + {B}_7Foreign\; Born_i + {B}_8Political\; Ideology_i \cr &\quad+ {B}_9Satisfaction\; With\; Economy_i \cr &\quad+ {B}_{10}Institutional\; Distrust_i + \varepsilon _i} $$

$$\eqalign{ &General\; Democratic\; Evaluation_i \cr &\quad= a_i + {B}_{1}Woman_{i} + {B}_2Age_i + {B}_3Education_i + {B}_4Income_i \cr &\quad+ {B}_5Unemployed_i + {B}_6Union\; Member_i \cr &\quad + {B}_7Foreign\; Born_i + {B}_8Political\; Ideology_i \cr &\quad+ {B}_9Satisfaction\; With\; Economy_i \cr &\quad+ {B}_{10}Institutional\; Distrust_i + \varepsilon _i} $$The second section examines how respondents evaluate each of the specific characteristics in their country to test the claim that women are more critical about how democratic institutions work for them. The third set of analyses examine the main research question, focusing on how respondents rate the importance of each aspect of the democratic system for the 29 countries in the sample. These models follow Equation 1, replacing only the dependent variable with each of the 13 indicators of specific democratic institutions. Finally, we analyzed the relationship between respondents’ gender and their conceptions of democracy separately for each country in our sample. The equation for these 377 multivariate models isFootnote 4

$$\eqalign{ &Importance\; of\; Component\; of\; Democracy \cr &\quad= \alpha + {B}_1Woman_i + {B}_2Age_i + {B}_3Education_i + {B}_4Income_i \cr & \quad+ {B}_5Unemployed_i + {B}_6Union\; Member_i + {B}_7Foreign\; Born_i \cr &\quad + {B}_8Political\; Ideology_i + {B}_9Satisfaction\; With\; Economy_i \cr &\quad + {B}_{10}Institutional\; Distrust_i + \varepsilon _i} $$

$$\eqalign{ &Importance\; of\; Component\; of\; Democracy \cr &\quad= \alpha + {B}_1Woman_i + {B}_2Age_i + {B}_3Education_i + {B}_4Income_i \cr & \quad+ {B}_5Unemployed_i + {B}_6Union\; Member_i + {B}_7Foreign\; Born_i \cr &\quad + {B}_8Political\; Ideology_i + {B}_9Satisfaction\; With\; Economy_i \cr &\quad + {B}_{10}Institutional\; Distrust_i + \varepsilon _i} $$RESULTS

Overall Attitudes Toward Democracy

An initial exploration of descriptive statistics and bivariate fixed effects models suggests that women tend to be slightly less satisfied with democracy and consider their country slightly more democratic than men. However, there is no statistically significant difference between men and women respondents in how important it is for them to live in a democratically governed country. On average for our 29 countries, respondents were slightly dissatisfied with the way democracy works in their country (i.e., the mean scores are −0.53 for men and −0.41 for women in a scale that runs from −5 to 5); they evaluated their countries as fairly democratic (i.e., the mean scores are 1.33 for men and 1.35 for women); and they believed that living in a democratically governed country is very important (i.e., the mean scores are 3.58 for men and 3.55 for women, although this difference is not statistically significant).

The output from multivariate models with country fixed effects is presented in Table 1. The models predicting satisfaction with democracy and the evaluation of the current state of democracy in the country performed rather well. The full models explain 25% or more of the variation in the dependent variable. However, when predicting the more theoretically abstract idea of the importance of being democratically governed, the full model was relatively weak.

Table 1. Overall attitudes toward democracy in fixed-effects models estimated using poststratification weights.

SE, standard error.

*Indicates significance at .05.

The multivariate models painted the same picture as the bivariate regressions and descriptive statistics. First, we observed a negative and statistically significant relationship between being a woman and satisfaction with democracy. Second, women tended to rate their country as being more democratic than men. The result may indicate that women recognize their country as democratic, even to a greater extent than men do, but nonetheless they are less satisfied with how democracy works for them. The size of the coefficients was quite small because experiences with democracy are not solely or primarily determined by gender. It is striking, however, that even after controlling for a host of other factors, women were systematically less satisfied with democratic institutions than men. Finally, we detected no statistically significant difference between women and men in terms of how important it is for them to live in a democracy.

Evaluation of Specific Democratic Institutions

Before analyzing women and men's views about the relative importance of specific aspects of democracy in the following section, we examine in more detail the claim that women are more critical of how democratic institutions perform in their country. Descriptive statistics and bivariate fixed-effects models demonstrated a statistically significant gender gap for 11 of the 13 characteristics when respondents are asked to evaluate how well each of these aspects of democracy work in their country (Table 2).

Table 2. Evaluations of democracy in country by gender—descriptive statistics from country fixed-effects binary models calculated using survey weights

SE, standard error.

Variables are measured from −5 (not at all) to 5 (completely).

*Indicates statistical difference at p < .05.

Table 3 presents the results of multivariate models for the entire sample, including country fixed-effects. Even after controlling for other sociodemographic characteristics and political attitudes, women were more critical concerning 10 of 13 characteristics. Women evaluated only one democratic indicator (the country's use of referendums) more positively than men. If women tend to be less satisfied with democracy and more critical of most democratic institutions in their country, why do they consider it important to live in a democracy as much as men do?

Table 3. Individual level variables predicting respondent evaluation of democracy in respondent's own country in fixed-effects models estimated using poststratification weights

SE, standard error.

*Indicates significance at .05.

Importance of Specific Institutions for Democracy

Table 4 presents descriptive statistics and bivariate models for 13 indicators of citizens’ views about the importance of specific democratic practices. As a reminder, respondents were asked to rate how important each feature is for democracy. The descriptive statistics convey that both women and men viewed most of these practices as highly important aspects of democracy. The lowest rated characteristic was that “voters discuss politics with people before they vote,” with mean values of 2.49 for men and 2.41 for women, on the scale from −5 to 5.

Table 4. Importance of institutions by gender—descriptive statistics calculated using survey weights

SE, standard error.

Variables are measured from −5 (not at all) to 5 (completely).

*Indicates statistical difference at p < .05 through estimation of country fixed-effects bivariate models.

Table 4 shows not only that men and women differed on how important they consider 12 of the 13 characteristics but also that they tended to prioritize different institutions. Both groups agree on the five most important aspects of democracy. However, whereas men tended to see legal equality and free and fair elections as features of democracy that are much more important than any other institution, women were more likely to put as much emphasis on public justification and poverty alleviation. The rest of the indicators show even larger differences. For women, the reduction of income inequality, direct participation, and the protection of minority rights tended to be more important than party competition and freedom to criticize the government, whereas the opposite was true for men.

Table 5 presents the results from multivariate models, including individual-level control variables and country fixed effects. Statistically significant differences emerged between men and women for 11 of the 13 aspects of democracy included in the analysis. Even though the size of the coefficients is relatively small, it is comparable to the effects of other individual-level variables that one would expect to matter for political socialization. For example, for “opposition parties are free to criticize the government,” we calculated a statistically significant coefficient of −0.277 for gender. Thus, on average across all countries in our sample and after controlling for a host of other individual factors, women assigned to this aspect of democracy scores that were almost 3% lower than men's scores. To put this coefficient in perspective, the difference between men and women was similar in magnitude to a change of one standard deviation in the level of education and two standard deviations in the level of income. Similarly, the effect of gender on the importance of government reducing income differences (.25) was equivalent to the impact of being member of a union. Importantly, these coefficients captured average differences between men and women across 29 very different countries. As we show in the following section, the magnitude of this gender gap was much larger when we focused on specific countries.

Table 5. Individual level variables predicting importance of institutions for democracy in country fixed-effects models estimated using poststratification weights

*Indicates significance at .05, standard errors in parentheses.

Women tended to assign lower importance than men to seven aspects of democracy, most of which are related to institutions that enhance power asymmetries associated with gender relations. Conversely, women were more likely to give higher scores to four aspects of democracy that are less exposed to gender inequalities. For the most part, these results confirm H 1 through H 6.

In H 1, we expected women to consider representative institutions less important for democracy than men. Our analyses show a negative and statistically significant coefficient in the model for “free and fair elections.” The difference is relatively small in magnitude, and both women and men see elections among the most important aspects of democracy (i.e., the mean values for men are 3.99 and 3.91 for women). The result is not surprising given the centrality of elections in contemporary democracies for the exercise of several democratic practices. Yet, as mentioned before, for women, the difference between the mean values for free and fair elections and the next most important institution (the government explains decisions) was minimal, whereas it was larger for men (Table 4).

The largest negative coefficients are related to practices that emphasize the conflictual aspects of democratic politics: media and opposition parties are free to criticize the government, and governing parties are punished in elections when they have done a poor job. Moreover, men and women tended to rank these indicators differently in relation to other aspects of democracy (Table 4). As expected by H 2, women tended to see intermediary institutions (political parties), which have been historically dominated by men and that disproportionately benefit men over women, as less important for democracy. However, we did not find a statistically significant difference between men and women in the importance they assign to political parties offering clear alternatives. Both men and women considered it among the least important aspects of democracy included in the ESS survey.

Women respondents also tended to view institutions associated with interpersonal deliberation as less important for democracy, as predicted by H 5. The result is prominent for the role of the media in criticizing the government and in providing reliable information. However, we detected a significant result when exploring the importance of voters discussing politics with people they know.

Women instead tended to place more importance than men on institutions related to direct participation in decision making, supporting H 3. However, regarding H 4, we found mixed results for institutions related to the equal protection of civil, political, and social rights. The models show statistically significant gaps in the expected direction for two indicators: the government protects all citizens against poverty and the government tries to reduce differences in income levels. Interestingly, the coefficient for gender is the largest in a positive direction in the model predicting the importance of reducing income inequality. Clearly, women view democracy as more than just basic electoral institutions and constitutional norms, which is unsurprising given the well-known association between gender and income inequality in countries across all levels of economic development. Whereas the mean score for measures against income inequality is almost the lowest among all 13 indicators for men, women considered it among the most important aspects of democracy. Although most theories of democracy see poverty alleviation and economic redistribution as outcomes of democracy rather than as part of its defining features (although see Marshall Reference Marshall1950 and Somers Reference Somers2008), citizens—especially women—clearly disagree.

Against the predictions of H 4, women placed less importance than men on legal equality (i.e., courts treat everyone the same). Still, they considered it the most important aspect of democracy. The small negative difference in their mean scores for this indicator may be related to women's skepticism toward judicial bodies that have historically been controlled by men and often blocked progress for women's causes (Sommer Reference Somers2008). Similarly, we found no statistically significant difference in how men and women scored the importance of protecting minority rights. However, despite providing similar mean scores as men, women ranked the protection of minority rights above other aspects of democracy that men instead tended to prioritize (see Table 4).

Finally, H 6 predicted that women would assign greater importance to practices of intrapersonal deliberation. Interestingly, both men and women viewed the public justification of political decisions by government officials as one of the most important components of democracy. However, on average, women assigned slightly higher scores than men to this aspect of democracy, and women considered public justification as important as free and fair elections, which is a core component of democracy.

Overall, these models provide empirical support for H 1 through H 6. Women assigned lower importance to those aspects of democracy that are disadvantageous for them (representative institutions, intermediary bodies, and interpersonal deliberation). On the contrary, women prioritized democratic institutions that are either less exposed to gendered power asymmetries (i.e., direct participation and public justification) or that actively try to revert them (i.e., equal protection of civil, political, and social rights). The results for only two of the 13 indicators go partially against the expectations of the theory: equal treatment by the courts and protection of minority rights.

Importance of Specific Institutions by Country

The results from the previous section show significant differences between men and women respondents in terms of which institutions they considered more important for democracy. We now explore how these differences play out in each country in the sample. The statistical models follow the same set up as the models from the previous section, but the effects of gender on respondents’ views about the importance of each democratic component have been estimated separately for each country.

Figure 1 plots the estimated effect of gender for each of the 377 models with confidence intervals. In the left-hand panel, the y-axis sorts the countries in our sample in descending order according to the 2012 values of the Electoral Democracy Index; the y-axis in the right-hand panel maintains the original scale of the index. The Electoral Democracy Index is an expert-based measure of the overall quality of democracy in the country developed by the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project (Lindberg et al. Reference Lindberg, Coppedge, Gerring and Teorell2014). The index ranges from 0 to 1 where a score of 1 means the highest quality of democracy.

Figure 1. Coefficients for predicting importance of characteristics for democracy by country and V-Dem score (woman coefficient shown).

Figure 1 provides some tentative support for H 7. Statistically significant differences in men and women's conceptions of democracy are more frequent in countries with higher scores in the Electoral Democracy Index. These gender gaps are more common and larger in countries like Belgium, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Netherlands, and Norway, all of which have high scores in the Electoral Democracy Index (Tables 6 and 7). Notice also that the size of many of these differences is much larger than in the pooled models. For example, in the United Kingdom and the Scandinavian countries, differences between men and women are as large as 7%.

Table 6. Number of significant gender coefficients for predicting importance of characteristics for democracy by country

Table 7. Democratic attitudes and democratic scores by country—descriptive statistics

As the quality of democracy decreases, gendered differences in conceptions of democracy become smaller and increasingly rare. Notably, in the vast majority of cases, the direction of the statistically significant coefficients in these country-specific models is consistent with the findings of the pooled models in the previous section (see Tables F1 and F2 in the Supplementary Appendix, where we report the coefficient and standard errors for the gender variable for the 377 models).

Finally, H 8 stated that more differentiated views of democracy should be associated with stronger democratic attitudes. Table 7 lists the number of indicators for which we found a statistically significant difference between men and women with the country means of respondents’ support, satisfaction, and evaluations of democracy. Citizens tended to be more satisfied with and less critical of democracy in countries where we found evidence of gendered differences in conceptions of democracy. Countries with more differentiated views tended to have higher means (at least 3.19 in a −5 to 5 scale) for the question about how important it is to live in a democracy, whereas there was more variation among countries with less differentiated conceptions of democracy (ranging from 1.51 in Russia to 4.51 in Cyprus).

To be sure, these are not fully fledged statistical tests of H 7 and H 8. A proper assessment of the mechanisms proposed by these hypotheses would require detailed country-level data on gender asymmetries for each institution. Such a task represents an obvious next step for future work, but it falls outside the scope of this article given the early stages of this research agenda.

CONCLUSION

This article contributes to the literature in gender and democratic attitudes by showing that men and women harbor different views about which institutions are more important for democracy. Our analyses provide evidence that men and women tend to prioritize different aspects of democracy based on how those institutions have typically advantaged or disadvantaged their influence over political processes. The size of the effect of gender on conceptions of democracy is relatively small, although it is not negligible, especially when looking at specific aspects of democracy in particular countries, and it is comparable to the effects of most other sociodemographic characteristics. The fact that we find statistically significant differences in men's and women's understandings of democracy, and that these differences follow a theoretically meaningful pattern even after controlling for other factors, makes a strong case for further research into the topic.

The gender gap in conceptions of democracy is not associated with different levels of democratic support. On the contrary, men and women ESS respondents were more likely to prioritize different aspects of democracy in countries with more robust democratic systems. This result suggests that both groups tend to develop stronger democratic attitudes in countries in which they are able to develop differentiated views about which aspects of democracy are most important for them.

The findings presented here have broader implications for our understanding of how citizens think about democracy in their everyday lives. Rather than committing to abstract “models of democracy,” people value democracy when it provides them with spaces for political agency despite broader power asymmetries present in society. If this argument is correct, political regimes do not need to conform to a particular model of “democracy with adjectives” to foster democratic support among their citizenry; rather, they must develop diverse institutional systems that empower citizens with different positions and endowments to exercise their political agency.

Future research on this topic should examine in more detail the causal mechanisms that foster more differentiated views in high-quality democracies. For instance, extending our analysis to the American context could potentially generate important insights about these mechanisms. On the one hand, despite recent setbacks, the United States has historically been at the top of democracy rankings (e.g., V-Dem's Electoral Democracy Index for 2012 was .93, situating the country at the top of the list in Table 8). On the other hand, the gender gap in political empowerment in the United States is much wider than in most countries with similar levels of democratic quality; the 2012 Global Gender Gap Report ranked the United States in place 55 of 135 countries (Hausmann, Tyson, and Zahidi Reference Hausmann, Tyson and Zahidi2012). To what extent do these gender gaps reflect a rich democratic ecosystem that nonetheless perpetuates gendered inequalities? If so, how does this affect how men and women understand democracy? Extending a gendered lens to the analysis of American political culture may open interesting insights about how the “American ethos” (McCloskey and Zaller Reference McCloskey and Zaller1984) or “America's multiple traditions” (Smith Reference Smith1993) may have shaped different conceptions of democracy among men and women in the United States.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X19000473