Populist radical right parties are generally perceived as Männerparteien—that is, to paraphrase Abraham Lincoln, political parties of men, by men, and for men—in which women play little role. They are led by strong men, who promote a traditional image of hypermasculinity and propagate misogynist and sexist positions. Long-term party leaders such as Jean-Marie Le Pen of the French National Front (Front National, FN) and Umberto Bossi of the Italian Northern League personify this media image with their often boorish and sexist behavior—Bossi infamously said the Lega had a “hard-on” to indicate that the party had staying power. But while men still dominate the leadership of populist radical right parties, as they do all party families, for years the most prominent radical right leader in Europe has been female, Marine Le Pen, and she is not the only woman leading a populist radical right party.

In 2011, Jean-Marie Le Pen passed leadership of the FN on to his youngest daughter, Marine, who has sought to modernize the party's image by declaring a de-demonization (dédiabolisation) strategy. Since her ascension, the FN,Footnote 1 once a political pariah isolated by a so-called cordon sanitaire, has claimed a programmatic transformation and experienced some level of “normalization,” at least compared with the years under her father's leadership. This “electoral rejuvenation” under female leadership has been accompanied by a boost in media coverage presenting the more amenable face of the party and its possible foray into the mainstream (Ivaldi Reference Ivaldi2015, 1; Mayer Reference Mayer2013; Shields Reference Shields2013).

The increasing “mediatization” of politics has made the images of political actors conjured by the mass media an important factor to consider in the electoral process. Media frames can be understood as “interpretive package(s)” that give priority to a certain explanation or narrative of an event (Yarchi Reference Yarchi2014). Framing is defined as the process through which some aspects of reality are selected and made more salient in a text, “in such a way as to promote a particular problem definition, causal interpretation, moral evaluation, and/or treatment recommendation for the item described” (Entman Reference Entman1993, 52). In other words, framing refers to how issues are reported by news media as well as what is emphasized in such reporting. Framing can also affect which considerations the public weighs when digesting political issues, and thus the media can profoundly shape public opinion even without any explicit attempt at persuasion or manipulation (Schlehofer et al. Reference Schlehofer, Casad, Bligh and Grotto2011, 70).

Inevitably, media framing of political phenomena is not gender-neutral. For example, female politicians often face a considerable amount of gender-biased coverage that perpetuates stereotyped narratives. Language choice is a crucial component in establishing frames, and scholars often point to stereotypical language in the media discussing or describing female politicians that indicates subtle (and not so subtle) gender-biased coverage. Interpreting the lens through which a woman is seen in the media (i.e., the quality of her coverage) has proven to be a difficult task for researchers (Carlin and Winfrey Reference Carlin and Winfrey2009; Falk Reference Falk2010).

Nevertheless, media content analyses of female politicians have mostly concluded that the content and tone of coverage of women either in electoral campaigns or in office differs significantly from that of their male counterparts. Specifically, irrespective of whether news media choose to focus on the personality or policy stands of a female politician, they often “portray women in a harsh light with respect to their male counterparts” (Campus Reference Campus2013, 39). Much of the literature on gendered media framing underlines the ways in which women are stereotyped, with female political candidates’ appearance, family status, and personal lives outplaying their politics in almost every instance (Bystrom, Robertson, and Banwart Reference Bystrom, Robertson and Banwart2001; Falk Reference Falk2010; Fridkin and Kenney Reference Fridkin and Kenney2014; Norris Reference Norris and Norris1997).

Assumptions about race, class, and gender consistently underpin media coverage of political candidates, as journalists choose which issues and events to cover, whom to quote, and how to frame the narrative. While scholars have raised concerns regarding the biased news coverage of female politicians, less research addresses the intersectionality of female political actors’ identity in the media context. Intersectionality, a concept introduced by the U.S. critical race theorist Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw (Reference Crenshaw1989), denotes the various ways in which these identities interact to shape the multiple dimensions of marginalization. It describes the ways in which identity categories are “both mutually constituted and mutually constitutive,” thereby rejecting the possibility of universalizing women's experiences (Ward Reference Ward2017, 44). Rather than considering multiple identity axes as cumulative, intersectional research emphasizes that women's experiences are a result of the intersection between these divergent social categories as well as the context in which an interaction takes place (Yuval-Davis Reference Yuval-Davis2007). Not withstanding the growth in intersectional research in recent years, intersectional identities and their impact on political life are rarely explored in political science or in the interdisciplinary subfield of political communication, which limits our understanding of the specific contextual challenges faced by these women in the media context (Hancock Reference Hancock2007).

Global politics is witnessing a rise in the number of female right-wing politicians in leadership roles. While women are often underrepresented in rightist parties, those in leadership positions “have captured significant media attention and given right-wing politics a female face” (Schreiber Reference Schreiber2008, 23). Gender and politics scholars have been increasingly responsive to this, and growing attention has been paid to the heterogeneity of women as political actors (Celis and Childs Reference Celis and Childs2012; Deckman Reference Deckman2016; Schreiber Reference Schreiber2008, Reference Schreiber2010, Reference Schreiber2014). So far, however, no one has researched the specific case of female radical right leaders in the media. We do not argue that this political identity functions in the same way as ascriptive identity axes traditionally used in intersectional analyses. However, we borrow intersectionality's conceptualization of the relationship between identity categories and apply this in our analysis, positing that the effect of the radical right identity causes qualitatively different gendered media framing of female politicians. This article will focus on the case of Marine Le Pen, femme politique and leader of the FN, and the way in which the “harder” frame of her populist radical right ideology interacts with the “softer” frame of her female identity in media coverage.

The article is organized as follows: First, we focus on the often-troubled relationship between female political leaders and the media, highlighting the key ways in which the media either overtly or subtly use gender stereotypes in their depiction of women in politics. This is followed by a review of the literature on the media framing of populist radical right parties. In the third section, we discuss the theoretical framework of intersectionality in general, and with regard to female populist radical right politicians in particular, highlighting the ways in which the gender and populist radical right frames are crosscutting rather than overlapping. We then introduce our data and method, followed by concise overviews of the media coverage of Marine Le Pen in four French and U.S. newspapers and an assessment of the presence of the gender and populist radical right frames in the different media. We end the article with a discussion of the implications of the findings for the study of female politicians in general and populist radical right female politicians in particular, and we suggest some avenues for future research.

GENDER FRAMING IN THE MEDIA

Women face numerous barriers on their path to assuming a political role, including the disjuncture between stereotypically “feminine” traits and predominantly masculine notions of leadership. Since power and leadership have historically been in the hands of men, traits commonly associated with leadership continue to coincide with stereotypical traits of masculinity: ambition, assertiveness, confidence, and dominance. Women, however, are assumed to possess quite different psychological traits: kindness, collaboration, warmth, and gentleness (Eagly and Carli Reference Eagly and Carli2003). As Kellerman and Rhode argue, “one of the most intractable obstacles for women seeking positions of influence is the mismatch between qualities traditionally associated with women and those traditionally associated with leadership” (2007, 6). This phenomenon is commonly referred to as the “femininity-competence double bind,” whereby women who are considered feminine are judged to be incompetent, and women who are considered competent are judged to be unfeminine (Campus Reference Campus2013; Jamieson Reference Jamieson1995). This problem of perceiving women as viable leaders is often maintained and propagated by a mass media that seeks to oversimplify complex issues and overemphasize dichotomous models of conflict.

Although overt expressions of sexism are increasingly uncommon in mainstream media, gender bias permeates press coverage in subtler ways. Research on women and politics has consistently shown that gender stereotypes, such as masculinized leadership styles, influence how female politicians are represented by the media. The stereotype of the incompatibility between femininity and competency is theorized to be a consequence of “benevolent sexism,” whereby ostensibly positive stereotypes, such as being caring and collaborative, may have negative implications for female candidates (Campus Reference Campus2013; Glick and Fiske Reference Glick and Fiske2001). Female politicians must balance the gendered frame, which urges them to be sensitive and gentle, with the masculinized leadership frame, which asks them to appear assertive and unemotional. Since the media is the primary source of the “symbolic material out of which people construct their understanding and evaluation of political actors,” media practices are significant in perpetuating and even emboldening these prejudicial cultural narratives (Wasburn and Wasburn Reference Wasburn and Wasburn2011, 1028).

Scholars have showed that women receive more focus on personality attributes than on political issues. The literature suggests that men often receive greater attention to their experience, accomplishments, and policy positions, while female leaders tend to be described in terms of their “personal characteristics” (e.g., Shepard Reference Shepard2009). Studies of U.S. presidential primary elections support the persistence of this gender bias in the content of coverage. For example, a newspaper study of Elizabeth Dole's 2000 presidential bid found that “readers were more likely to learn about the policy positions of Bush, McCain, and Forbes than they were to discover what Dole stood for and how she planned to govern the country as president” (Aday and Devitt Reference Aday and Devitt2001, 61). Even though female politicians, compared with male politicians, are more likely to make public policy issues a cornerstone of their campaigns, they are less likely to have their positions on these issues featured in the news (Bligh et al. Reference Bligh, Schlehofer, Casad and Gaffney2012). These findings are not unique to the United States, as studies of media in Australia (e.g., Hall and Donaghue Reference Hall and Donaghue2013), Canada (e.g., Gidengil and Everitt Reference Gidengil and Everitt1999), and various European countries (e.g., Garcia-Blanco and Wahl-Jorgenson Reference Garcia-Blanco and Wahl-Jorgensen2012) show.

Research on the content of media messages in the United States also consistently finds that the media link “male issues” (security, foreign affairs, economy) to male politicians and “female issues” (education, welfare, health care) to female politicians (Bystrom, Robertson, and Banwart Reference Bystrom, Robertson and Banwart2001; Campus Reference Campus2013; Kittilson and Fridkin Reference Kittislon and Fridkin2008). As discussed, female politicians face a femininity-competence double bind: if their personality is described in terms such as “warm” or “compassionate,” they may appear to the public as ill suited to tackle more “masculinized” policy arenas, such as the economy and military affairs (Carroll and Fox Reference Carroll, Fox, Carroll and Fox2006; Wasburn and Wasburn Reference Wasburn and Wasburn2011). However, if the media describe them as “competent” or “tough,” female politicians risk alienating (female) voters, who favor more traditional family roles (Huddy and Terkildsen Reference Huddy and Terkildsen1993). The long-held assumption in the United States remains that the political expertise of women is limited to a range of domestic social issues, such as welfare and education policy. While women might benefit from increased media attention to these specific “feminized” issues, they may also have a harder time influencing the media's agenda than their male counterparts do (Kahn Reference Kahn1996; Wasburn and Wasburn Reference Wasburn and Wasburn2011).

Third, female politicians are described and trivialized by the media's use of gender-specific language (Braden Reference Braden1996). For example, Cameron (Reference Cameron1992) theorized that certain linguistic titles, such as “sir,” “mister,” “senator,” or “doctor,” have been developed as recognitions of respect and power status. Women are often stripped of these titles in and out of the media (Carlin and Winfrey Reference Carlin and Winfrey2009; Kahn Reference Kahn1996). Analysis of U.S. congressional races indicates that female politicians are often taken less seriously at the beginning of a campaign and are referred to by their first names, while their male counterparts are not stripped of their title and are mostly called “mister” (Fox Reference Fox1997). In the French 2012 presidential elections, Ségolène Royal, a candidate in the Socialist Party primary, was far more frequently referred to by her first name than her male competitors, which had the effect of “reducing her presidential stature and even infantilizing her” (Murray Reference Murray2012, 49).

Another closely related type of problematic framing of female politicians is the media's undue focus on women's physical appearance. The personalization of politics has resulted in the media's emphasis on the image of candidates, both male and female. However, the media do not present objective descriptions of candidate appearance; rather, the media “highlight, underplay, or diminish particular features of candidates … These media-shaped images conveyed to voters … become powerful symbols that identify and/or define a candidate” (Kotler and Kotler Reference Kotler, Kotler and Newman1999, 5). Research has shown that the physical image of female politicians is overemphasized, often at the expense of other noteworthy aspects, such as her character or political issue positions. In her seminal study of U.S. presidential candidates, Falk (Reference Falk2010) counted the number of physical descriptions of each candidate in press reports. On average, she discovered that women received approximately four physical descriptions for every one applied to men. Importantly, she also underlined that there has been no substantial change since the first female presidential candidate in 1872. Case studies analyzing media attention to female politicians’ appearance validate this finding. For example, Elizabeth Dole's candidacy was framed in terms of her personal and physical traits, with the press giving more attention to these traits than to the same characteristics of her male counterparts. Furthermore, when her appearance was highlighted, the media commentary was mostly negative, which was not the case for her male adversaries (Heldman, Carroll, and Olson Reference Heldman, Carroll and Olson2005). In the 2008 Hillary Clinton campaign, particularly in television and online news and blogs, instances of sexist coverage overemphasizing the appearance of Clinton rose significantly (Carroll Reference Carroll2009; Lawrence and Rose Reference Lawrence and Rose2010).

Studies of U.S. vice presidential candidates indicate that the two women running for vice president, Geraldine Ferraro in 1984 and Sarah Palin in 2008, clearly received more coverage mentioning their dress and physical appearance than male candidates (Carlin and Winfrey Reference Carlin and Winfrey2009; Heldman Reference Heldman2009). The sexism displayed in the media toward Palin was particularly misogynistic, highlighting the fact that, despite claims that media outlets have become more gender conscious, the volume of gender-biased coverage has actually increased dramatically. In Palin's case, sexist portrayals originally stemmed from her beauty queen pageant background, her youthful appearance, her wardrobe, and her “unabashed feminine nonverbal communication such as winking” (Carlin and Winfrey Reference Carlin and Winfrey2009, 330). This overemphasis of the physical appearance of female politicians in the media often deflects discussion of qualities related to governmental office (Heflick and Goldenberg Reference Heflick and Goldenberg2009).

Lastly, the media focus disproportionately on the family lives of female politicians. While the family of a male politician is seldom a primary object of media attention, the fact that female political leaders are wives, mothers, or daughters is intensely scrutinized. Carlin and Winfrey (Reference Carlin and Winfrey2009) detail the mother frame used by the media as a stereotype with several dimensions. First, women are perceived as being caring, understanding, and closer to the average voter, a potential advantage to a campaign (Jost Reference Jost2008). Second, this same frame can also be perceived as a woman's inability to form leadership roles, since her maternal responsibilities take precedence. A third, potentially damaging application of the mother frame involves “images of scolding, punishment, or shrewish behavior” (Carlin and Winfrey Reference Carlin and Winfrey2009, 328). Carlin and Winfrey found that the mother frame was prominently and repeatedly included in news stories on Sarah Palin and Hillary Clinton during their (vice) presidential campaigns. Specifically, both women faced significant scrutiny as to whether they could be successful leaders and mothers. It is important to highlight the fact that these female candidates, as well as others, are agentic in these campaign choices, and they often purposefully contributed to the formation of certain metaphors and stereotypes. Nevertheless, their choices were shaped and constrained by the often-prejudiced norms of the political and media environment.

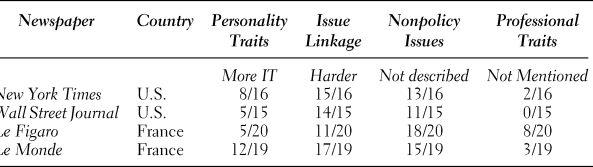

In short, the common gender frame for female political leaders in the news media (1) is less negative; (2) focuses disproportionately on expressive personality traits (warm, collaborative, etc.); (3) rarely mentions prior professional accomplishments and experience; (4) links them mainly to “softer” issues (women's rights, gay rights, welfare); and (5) gives much attention to nonpolicy and/or gender-specific issues, such as physical appearance or family life. However, the media framing of politicians such as Marine Le Pen is not only affected by their (female) gender but also by their (populist radical right) ideology.

POPULIST RADICAL RIGHT FRAMING AND THE MEDIA

As economic and competitive pressures have forced traditional media to search for a larger audience, it has been hypothesized that the quality of the information content has given way to sensationalism and superficiality—news reporting that focuses “more on personalities than on policies” (Ellinas Reference Ellinas2010, 34). This media “simplism” creates an environment conducive to the populist radical right, whose often exaggerated references to “ethnic” crime and tension and its “us vs. them” mentality is “in line with a media appetite for monocausal explanations and for the delivery of easy solutions to complex phenomena” (Ellinas Reference Ellinas2010, 34). Tabloids and commercial television, in particular, share the authoritarian, nativist, and populist sentiments of populist radical right parties and offer oversimplified solutions in line with those of radical right parties (Mudde Reference Mudde2007, 249). Charismatic leaders, whom these parties are often known for, employ a populist style that “shares the key traits of media logic, including personalization, emotionalization, and an anti-establishment attitude,” which can lead in some media sections to more attention (Bos, Van der Brug, and De Vreese Reference Bos, Van der Brug and Vreese2011, 183).

Even though the media may have an affinity toward publicizing and exaggerating the rise of the populist radical right, in most cases, mainstream or “elite media” are unsympathetic, choosing to attack them and label them “extremists” (Mudde Reference Mudde2007). If the media portray a populist radical right party as “antidemocratic” or “outside the main realm of politics,” the result is a decrease in the party's effectiveness and legitimacy (Bos, Van der Brug, and De Vreese Reference Bos, Van der Brug and Vreese2011, 187). Media exposure of the populist radical right comes mostly in the form of denigration, for example, by disproportionate attention to the presence of right-wing extremists, from unreconstructed fascists to neo-Nazis to Holocaust deniers. These criminal or violent members at the fringe of the organization can lead to “intense, and unwanted, media exposure and increased stigmatization” (Art Reference Art2008, 424). Reporters and editors define a newsworthy story as one that has a “level of violence and/or conflict, possibilities for dramatization and personalization, and novelty” (Koopmans and Olzak Reference Koopmans and Olzak2004, 201). Hence, it is not surprising that linking these parties to their (alleged) fascist or Nazi roots and portraying scenes of protest violence is a common practice in traditional media coverage.

A content analysis of three Dutch newspapers from 1986 to 2004 found that coverage of the populist radical right was significant, with the parties often featured as a prominent actor in a headline or body text. However, populist radical right political actors “featured as much in roles in legal conflict as in political actuality, which is the normal every-day role of a political party,” and stigmatizing associations with extremity were used in a quarter of all coverage (Schafraad, Wester, and Scheepers Reference Schafraad, Wester and Scheepers2013, 22). In addition, the media persistently highlight the most controversial aspects of the populist radical right agenda, with xenophobic or exclusionist views being the only ideological standpoints to receive a relatively high level of attention with these parties. Finally, the vast majority of media attitudes toward these parties are negative, portraying the parties as “controversial outsiders” (Schafraad, Wester, and Scheepers 2012, 23). Though their “radicalization of mainstream views” (Mudde Reference Mudde2010) guarantees the populist radical right a consistent spot in the media, this quality also warrants consistent denouncements by the media.

In short, the common frame for populist radical right parties and politicians in the news media (1) is very negative (often including links to historical fascism and Nazism); (2) focuses disproportionately on instrumental personality traits (aggressive, ambitious, etc.); (3) rarely mentions prior professional accomplishments and experience; (4) links them mainly to “harder” issues (e.g., security, immigration, law and order); and (5) gives little attention to nonpolicy issues (particularly aspects that “humanize them,” such as family life).

COMPETING FRAMES? USING INSIGHT FROM INTERSECTIONALITY TO ANALYZE MEDIA FRAMING OF MARINE LE PEN

As a research tool for scholars in women and politics, employing intersectionality avoids the implicit construction of women as a homogenous group with a fixed identity (Crenshaw Reference Crenshaw1989; Hancock Reference Hancock2007). Intersectionality not only guards against essentialism and allows for inclusion of historically underprivileged voices, it also gives researchers a better theoretical tool for assessing gendered stereotypes in the media. Despite the growth in intersectional research, intersectional identities and their impact on political life are less explored in the field of political communication, which limits our understanding of the specific contextual challenges faced by many women in the media context (Gershon Reference Gershon2012; Hancock Reference Hancock2007; Simien Reference Simien2007).

Research on intersectionality in media coverage of political candidates mostly focuses on the combined effects of gender and race, often finding that minority women receive the most negative and infrequent media coverage compared with both white women and minority men (Tolley Reference Tolley2015; Ward Reference Ward2017). In her article examining media coverage of female representatives in the U.S. House of Representatives, Gershon (Reference Gershon2012) confirms previous studies, concluding that the tone and content of minority women's coverage was more negative than that of their white female counterparts. Additionally, Latina congresswomen diverged from their colleagues in the extent of their ethnicity-related issue coverage, specifically receiving significantly more coverage on immigration issues.

As the number of right-wing women participating in democratic politics has grown, and conservative female leaders such as German chancellor Angela Merkel and British prime minister Theresa May have become significant players on the world political stage, gender and politics scholars have realized the necessity of focusing on these female actors’ particular characteristics. Among other contextual differences such as race and class, party and ideological identities are given increasing attention in studies of women in politics (Ackerly and McDermott Reference Ackerly and McDermott2012; Celis and Childs 2014; Deckman Reference Deckman2016; Schreiber Reference Schreiber2008, Reference Schreiber2010, Reference Schreiber2014). Nevertheless, previous studies of rightist female politicians either analyzed the media narratives deployed for these female politicians in tandem with the media narratives used for female politicians generally or compared with their male counterparts (Carlin and Winfrey Reference Carlin and Winfrey2009; Heflick and Goldenberg Reference Heflick and Goldenberg2009; Heldman Reference Heldman2009; Schreiber Reference Schreiber2010; Wasburn and Wasburn Reference Wasburn and Wasburn2011).

More importantly, assumptions about how a woman's right-wing political affiliation may complicate identity categories remain largely unexamined. In that respect, conservative and populist radical right female politicians differ fundamentally. Whereas conservatism is broadly considered to be part of the political mainstream, including by liberals, the populist radical right is not. While it is true that the populist radical right is becoming increasingly mainstreamed throughout Europe (e.g., Akkerman, de Lange, and Rooduijn Reference Akkerman, de Lange and Rooduijn2016) and beyond (e.g., India and United States), this is definitely not the case for Marine Le Pen and the FN in France. Building on intersectionality's conceptualization of the relationship between identity categories, we suggest that the media treatment of the populist radical right as an identity category causes a qualitatively different kind of framing in the media coverage of female politicians, including conservative ones.

While populist radical right ideas are a major source of marginalization of ethnic and sexual minorities, and (though in decreasing ways) of women, too, they are often stigmatized in the mainstream media. Few major media sources are openly populist radical right or treat populist radical right parties as “normal” political actors—some of the few notable exceptions are the Austrian Kronenzeitung (at least for some periods) and, more recently, the British Daily Express (e.g., Art Reference Art2007). What makes the analysis of female populist radical right leaders particularly interesting is that the two media frames are largely juxtaposed with each other (see Table 1). In the case of female populist radical right leaders, the two frames are crosscutting and potentially weakening each other, rather than overlapping and strengthening each other. The only aspect on which media coverage of female and populist radical right politicians overlaps is the downplaying of accomplishments and experience.

Table 1. Gender and populist radical right media frames

Overall, the tone of the media coverage of female politicians is not negative, while that of populist radical right politicians is strongly negative. And when media emphasize expressive personality traits such as collaborativeness and warmth for female leaders, the focus is on instrumental traits such as aggressiveness and ambition for populist radical right leaders. In line with this, media will link female leaders to “soft” issues such as welfare and women's rights, but populist radical right leaders will be linked to “hard” issues such as immigration and security. Finally, while journalists tend to focus disproportionately on nonpolicy issues in stories on female leaders, such as their physical appearance or family, these “humanizing” aspects tend to be ignored in coverage of populist radical right leaders.

This following analysis focuses on how the “harder” frame of a populist radical right identity interacts with the feminine “softer” frame in the case of Marine Le Pen, the most prominent female populist radical right leader in the world. Does her softer, positive female appeal neutralize the harder, negative populist radical right stigma? Or do the two seemingly opposed frames blend together in one new female populist radical right frame?

DATA AND METHOD

To ensure a comprehensive analysis, we selected articles from four newspapers in two countries: Le Figaro and Le Monde in France and the New York Times and Wall Street Journal in the United States. Although all are considered high-quality newspapers (i.e., so-called broadsheets), they differ in many respects, providing us the opportunity to control and contrast in paired comparisons for several factors that media scholars have found to further influence the coverage of news. First, we analyze both French and U.S. newspapers, distinguishing between the coverage of domestic and foreign news and engaging cultural differences in the use of these frames, in line with previous research on cultural differences in news practices (e.g., De Vreese et al. Reference De Vreese, Banducci, Semetko and Boomgaarden2006; Quandt Reference Quandt2008; Semetko et al. Reference Semetko, Blumler, Gurevitch and Weaver1991). Second, we account for ideological bias, having selected both conservative (Le Figaro and Wall Street Journal) and liberal newspapers (Le Monde and New York Times).

The articles are analyzed on the basis of qualitative content analysis, in which the unit of analysis is the whole article (e.g., Kracauer Reference Kracauer1952; Mayring Reference Mayring2000).Footnote 2 Our analysis is deductive and analyzes frames that are defined and operationalized prior to the investigation. With regard to the two U.S. newspapers, we selected all articles with a significant focus on the FN or Marine Le Pen that were published between January 2011 and December 2014. For the two French newspapers, we used a slightly different selection method and period, as they understandably published far more articles on the FN and Marine Le Pen than their U.S. counterparts. Hence, we included only articles that focused on Marine Le Pen in a more in-depth manner and were published in a shorter time period, December 2012 to December 2014. The longer time period covers her takeover of the FN in January 2011, the 2012 French presidential and parliamentary elections, the prospects of the FN in the 2014 European Parliament elections, and the aftermath of its record-breaking score of the vote. The total number of selected articles per newspaper varied from 15 to 20 (see Table 2).Footnote 3

Table 2. Overview of selected news sources

ANALYSIS OF NEWSPAPERS

Before we analyze how the two frames of a female populist radical right leader such as Marine Le Pen interact in the media,Footnote 4 we present short overviews of her overall coverage in the individual newspapers. We start with the two U.S. newspapers, followed by the two French ones.

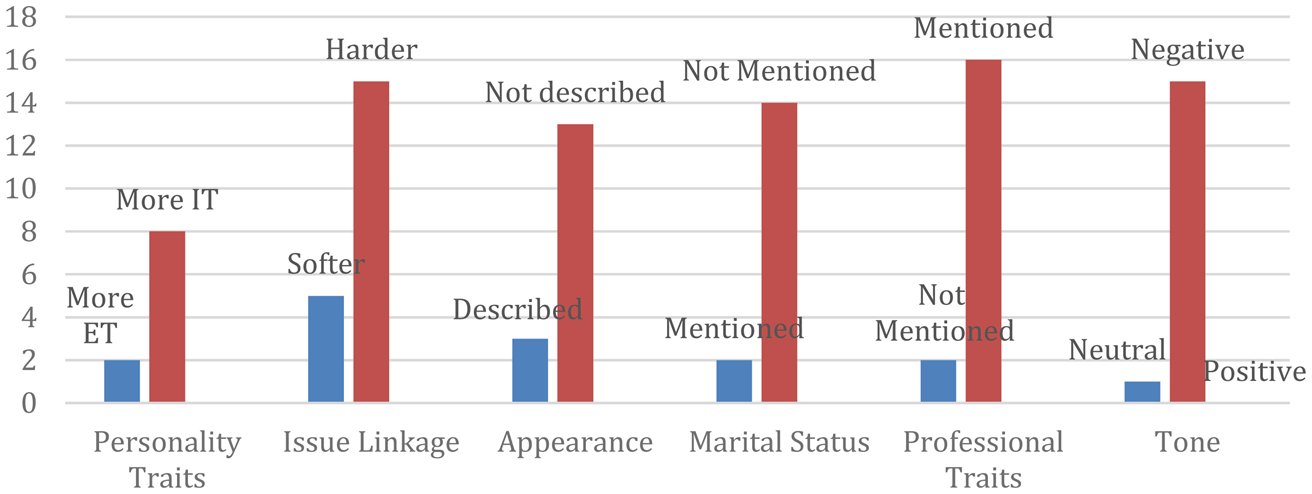

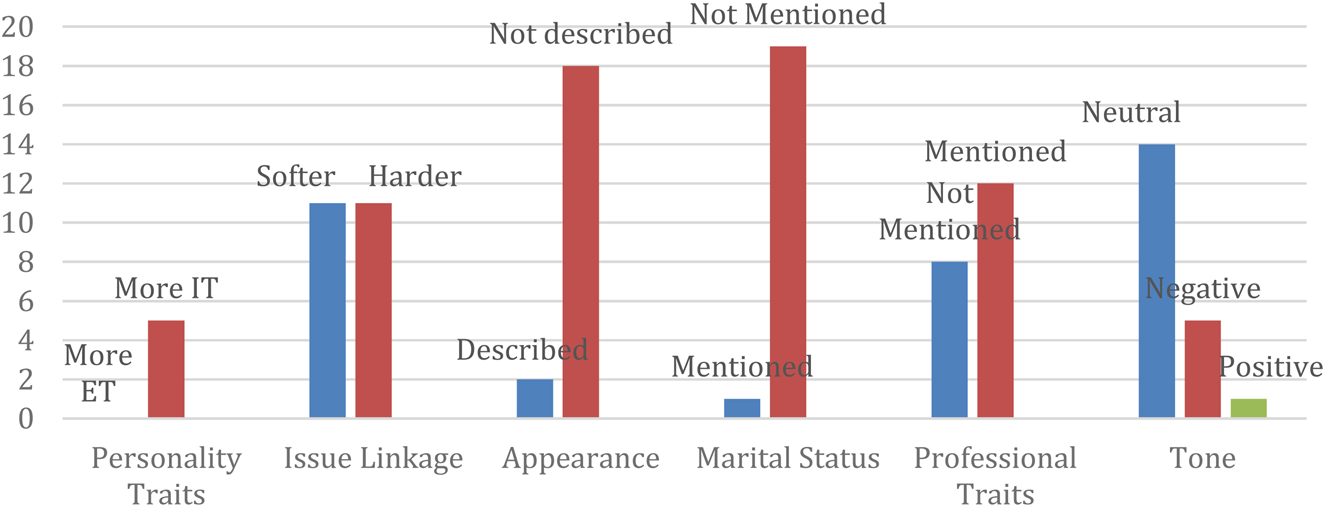

Table 3. Summary: Cross-national biased coverage Percentage of Articles Displaying Gender Bias

Table 4. Summary: Cross-national biased coverage Percentage of Articles Displaying Populist Radical Right Bias

New York Times

The New York Times covers Marine Le Pen and the FN overwhelmingly negatively, with only 1 of the 16 articles written in a neutral tone and none in a positive tone. The party's presence on the political scene is described as “toxic” and unwanted by all other political parties. One April 2012 article describes the FN as “France's grumpy party: they don't like Europe, they don't like bankers, they don't like immigrants.” Every article presents the party as exceptionally anti-immigrant, with a majority attributing its support to the racism of its white French members. The FN is also described as “an extremist threat” to both France and the European Union (EU). This threat is then typically emphasized by a narrow elaboration of characteristic populist radical right policy stances: anti-elitism, anti-EU membership, and anti-immigration are the most heavily cited stances in all the articles. About one-third (6 of the 16) of the articles also include a link to Nazism or fascism.Footnote 5

Describing the radical positions of a party to be warned against, New York Times journalists typically cite the infamous inflammatory rhetoric of Marine's father, Jean-Marie, as evidence of the party's extremism. The FN founder is described as “a racist demagogue,” and his anti-Semitic comments about the Holocaust are often referenced.Footnote 6 But they also consistently use Jean-Marie Le Pen and his incendiary, pejorative public comments as a point of comparison with Marine Le Pen and the FN under her leadership. The suggestion in almost every single article that discusses Marine Le Pen in detail is that liberalization of the FN has occurred, and that it is due to her leadership. One article title provides a particularly strong (and gendered) example of this media frame: “Marine Le Pen: France's (Kinder, Gentler) Extremist” (April 29, 2011). All articles describe her as “jettison[ing]” her father's anti-Semitism and “explicit racism” in efforts to “soften her party's image” by making it appear more moderate and “respectable.” Unlike her father, one article claims, Marine Le Pen is “electable.”

Although the de-demonization of the FN under a female leader is mentioned in nearly every single article, without substantial evidence as to how and why this has occurred, other aspects of gendered media bias are not as present. First, a description of her appearance “only” occurs in 3 of the 16 articles. However, in those articles, the description does serve to soften her presence. For example, one article states that her “commanding presence” is “softened by her husky voice,” while another article juxtaposes her “telegenic” quality with her father's harsher qualities. Second, her family life and marital status is not heavily emphasized. Only two articles note her children, her divorces, or her relationship with Louis Aliot (an FN vice president). Third, Marine Le Pen is mainly described in terms of instrumental personality straits. In the articles that discuss her personality, she is described as “authoritative,” “commanding,” “confident,” “ambitious,” and “strong.” One article describes her as “the daughter with the guts and political skills.” Only two articles make mention of her expressive traits. One does so in its title—the aforementioned “Marine Le Pen, France's (Kinder, Gentler) Extremist”—and the other juxtaposes her with her father by claiming that she is a more “conciliatory” political figure.

In terms of other aspects of gendered media coverage, the results are mixed. Marine Le Pen is primarily linked to softer issues when her policy stances are compared with those of her father. In this case, her support of gay rights, women's rights, and a strong welfare system is mentioned. However, the vast majority of the articles (10 of the 16) link her only to the harder issues associated with her party—mostly immigration, security, and the EU.

Wall Street Journal

The Wall Street Journal displays a higher level of neutrality in its FN coverage than its liberal counterpart, the New York Times. The bulk of the articles (11 of the 15) are neutral in tone, reporting on the FN party platform or the policy goals of Marine Le Pen without provocative remarks or partisan commentary. In addition, fewer articles link the party to fascism or Nazism. Nevertheless, four articles are written in a negative tone, and three allude to fascism or Nazism, suggesting, as articles in the New York Times do, that Nazi apologists “figured among the National Front's founders” and anti-Semitism is still rampant among party members. One of these articles, titled “The Ghosts of Europe” (May 27, 2014), even likens a quote by Marine Le Pen—“Our people demand just one politics. The politics of the French, for the French”—to one of the most-repeated Nazi slogans—“Ein Volk, ein Reich, ein Führer” (one people, one nation, one leader).

The Wall Street Journal consistently juxtaposes the viability of the FN under Marine Le Pen and the extremist controversy of the party's past under Jean-Marie Le Pen. Again, in nearly all articles, a provocative comment by Jean-Marie is referenced, and his daughter's ability to project “a more moderate image” by “dropp[ing] the party's xenophobic tones” is highlighted. However, no articles link Marine Le Pen solely to traditionally feminine or softer issues, such as health care or women's rights. Three articles link her to both hard and soft issues, but two of those articles only mention her support for the French welfare state in reference to her anti-euro economic plan. The third article, detailing an unofficial biography by Fourest and Venner (Reference Fourest and Venner2011), notes that the FN, with the “new spin” of Marine Le Pen, is now “a post-feminist supporter of women and gay rights.” Just one Wall Street Journal article characterizes Marine Le Pen with expressive personality traits, noting her “softer tone,” which (allegedly) allows her to gain a bigger following (May 23, 2014). But, generally, if an article mentions a personality trait, it is to highlight her “strength” as a leader capable of “taking the reins.”Footnote 7

The Wall Street Journal does not strongly express other aspects of gender bias. Marine Le Pen's appearance is described in four articles. The article that features the unauthorized biography recounts that she “was dubbed a tomboy” in her childhood. In addition, her two divorces and three children are mentioned in just 3 of the 15 articles. Finally, her professional accomplishments and experience are mentioned in an overwhelming majority of the articles (15 of the 17). Two articles further mention her career successes outside of politics, although most highlight her political successes after becoming leader of the FN.

Le Monde

In general, Le Monde’s coverage of the FN is much less shallow than the coverage in both U.S. newspapers. It continuously affirms its position that the FN is an “extreme right” party. While Marine Le Pen wages legal battles over the labeling of her party, in an effort to cut semantic ties with parties such as Golden Dawn in Greece, Le Monde journalists decidedly and repeatedly use this term to describe the FN. In one particular editorial titled “The Front National: Extreme Right Party” (October 4, 2013), the journalist writes, “We'll say it again clearly … the Front National is, today as it was in the past, an extreme right movement.” This and another article covering Marine Le Pen's court proceedings over the use of the extreme right label also emphasize the FN's roots: “neo-Fascists of the New Order and Nazi collaborators.”

Coverage of the party and its leader is mostly negative. Fourteen of the 19 articles display a negative bias against both the FN and Marine Le Pen, with three of the articles linking the party to fascist or Nazi ideology. One article even describes the presence of “small groups of skinheads” in attendance at one of her rallies, including that “some of them did not hide their hostility toward researchers and journalists also present at the rally.” An overwhelming majority, 17 of the 19, only note the party's stances on so-called radical right issues—immigration, Euroskepticism, and populist notions of a corrupt political mainstream elite. Only two articles cite the party's stance on other issues, but one of these articles merely focuses on Marine Le Pen's statement to abolish gay marriage if she were to be elected.

Le Monde frequently cites the past outbursts of Jean-Marie Le Pen in articles about Marine Le Pen. However, she is often described as being more similar to her father than different. The de-demonization strategy (dédiabolisation) is described as just that, a strategy. While it is noted that she has been successful in giving the party a “new image” in the eyes of a growing number of the French population, many of the articles contend that Marine Le Pen is an “adept tactician” whose party platform has “already been seen and already been heard” when her father led the party. Another article, titled “Marine Le Pen in the Steps of her Father” (December 11, 2014), admits that she gives the party a “more smooth and less caricatured” appearance, but it also links her statements about the use of torture to those made by her father when he was party leader. A similar article argues that some of her “sensational” (fracassantes) rhetoric undermines her strategy “to appear like a credible and responsible female politician.” An October 2013 editorial, finally, argues that Marine Le Pen has successfully created an image of a respectable party in the eyes of the electorate, but it concludes that “the president of the FN pulls the same strings as her father.”

Overall, gendered media bias is less present in Le Monde. Sixteen of the 19 articles (85%) mention her prior professional accomplishments and experience, and most note some of her past political successes, with the more recent articles at least noting her run for the presidency in 2012. Only one mentions her law degree, however. Additionally, Marine Le Pen is consistently linked to harder issues, most notably immigration, defense, security, economics, and the EU.

While two articles cite shifting political values of the French populace and legitimate FN doctrinal change, the language in other articles is much more accusatory of Marine Le Pen's strategy to “seduce” and convince her electorate of the normalization of the FN. One article labels her “an adept tactician” (fine tacticienne), and the word “strategy” is used repeatedly throughout the articles. Only one article mentions an expressive strength of Marine Le Pen, alluding to her “softer tone.” Instead, they focus on her politically calculated qualities. She is even described with such masculine expressions as “authoritative,” “blustery” (bravache), and “severe.” Only a minority, 4 of the 19, of these articles describe her appearance. Even out of these four articles, her appearance is not described as evidence of a softer party image. While her media-friendliness is acknowledged, other comments on her appearance simply include her smoking habit, and one even claims that she has “a severe face” (un visage sévère).Footnote 8

Le Figaro

The most striking difference found in Le Figaro, in comparison with Le Monde, is the absence of condemnation of the radical right party or its leader. A majority, 15 of the 20 articles, are not negative in their description of Marine Le Pen or her political stances. Fourteen remain neutral, and one article presents a positive perspective on the change of leadership from father to daughter. The article titled “Le Pen Father and Daughter: The Differences” (November 3, 2014) is symbolic of this stance. It argues that while Jean-Marie Le Pen focused solely on the spurring of controversy during his political career, his daughter's ambitions surpass this sort of marginality on the political scene. Le Figaro argues that Marine Le Pen has abandoned his racism and anti-Semitism to “concentrate on France's concrete problems” and “debate the ideas, not look for controversy.” Noting that Marine Le Pen believes that her project of dédiabolisation (de-demonization) has been achieved, the article claims that, for her father, diabolisation (demonization) was a method of existence on the political scene.

While this November 2014 article is the only one that seems to convey a completely positive image of Marine Le Pen, the 14 articles that remain neutral share the same positions on the FN under its female leader. Unlike her father, an article contends, Marine Le Pen “truly wants to get to business.” Interestingly, an equal number of articles link her to softer issues and harder issues. Moreover, 5 of the 11 articles that feature softer issue linkage only discuss those softer issues without also mentioning harder issues. Many articles discuss her economic policy, which features certain traditionally socialist policies, and her more liberal social views as being causes of her rise in power.Footnote 9 Her position on economics is repeatedly discussed as being quite different from her father's stances. Many articles state that her positions have moved to the left, “notably on the role of the state, public services, and the condemnation of ultra-liberalism.” Often, these articles are negative in nature, and this could be due to the fact that the newspaper's editorial stance has traditionally been conservative. One article, for instance, states that “Marine Le Pen today defends an economic plan with dangerous and illusory leftist themes.”Footnote 10

Other aspects of gendered media bias in Le Figaro are not present either. Only two articles in Le Figaro describes Marine's appearance, with one article noting that she “attracts the cameras to her” (March 28, 2014). If her personality is mentioned, her instrumental traits are highlighted. She is consistently described as being “capable,” “strategic,” “ambitious” (more so than her father in comparison), and “successful” as leader of the FN. Her marital status and family life are only mentioned in one article, which asserts that this part of her image is appealing to young people.

The five articles that exhibit a negative tone with regard to Marine Le Pen and her party are similar in content to the negative coverage in the other newspapers. When Marine Le Pen spoke of the acceptability of the use of torture, an article scorned her for acting “in the lineage” of Jean-Marie. Another particularly negative article, titled “Why the Front National Is Not Ready to Govern,” espouses the opposite viewpoint of many other Le Figaro articles, claiming that the party rests on a “cult of personality” and is devoid of intellectual, theoretical, or political foundation. Nevertheless, not a single Le Figaro article makes a link between the FN and fascism or Nazism. In addition, the political topics discussed in the articles are often variable, with seven articles limited to so-called populist radical right issues. Four articles do not mention any issue traditionally owned by the populist radical right.

DOES FRAMING OF THE RADICAL RIGHT NEGATE FEMININE FRAMING?

The analysis of the four individual newspapers uncovered some important differences and similarities. First and foremost, the interaction of bias related to the two categories analyzed here leads to a largely neutralized frame, absent of traditional indicators of implicitly sexist coverage. Expressive personality traits are mainly mentioned in just one or two articles, with a high of 2 out of 16 articles in the New York Times (12.5%). Linkages to “softer” issues are more common, roughly in one-quarter to one-third of the articles in all countries except for Le Figaro, which links Marine Le Pen to softer issues in a majority of its articles. Her physical appearance and marital status are also not that often mentioned, topping at just over 25% for physical appearance in the Wall Street Journal. This is in line with the previous observation that Le Figaro provides the least negative, and even slightly positive, coverage of Marine Le Pen and the FN. Contrary to expectation, all four newspapers mention professional accomplishments and experience in the vast majority of articles, but Le Figaro does so the least often, which goes a bit against its more positive, or neutral, framing.

With regard to the populist radical right frame, the picture looks quite different. Most articles that mention personality traits emphasize instrumental traits over expressive ones. This ranges from one-quarter of the articles in Le Figaro to almost two-thirds in Le Monde. In some 90% of the articles, in all but one newspaper, Marine Le Pen is linked to harder issues such as immigration and security; only in Le Figaro it is “just” in 55% of the articles. The situation is fairly similar with regard to the absence of nonpolicy issues, which ranges from a “low” 73% in the Wall Street Journal to a high 90% in Le Figaro. Again, in contrast to both the populist radical right frame and the gender frame, the presence of references to professional accomplishments and experience in the vast majority of articles (even in Le Figaro) is quite striking.

It is clear that the populist radical right frame is much more dominant in the news coverage of Marine Le Pen than the gender frame. Probably more surprising is that this applies to all newspapers, irrespective of whether they are U.S. or French or conservative or liberal—the only partial exception is the tone of the coverage, which was overwhelmingly negative in the two liberal newspapers but predominantly neutral in the conservative newspapers. Hence, we do not see a clear effect of the more shallow coverage of foreign news or of a strong political bias in coverage of domestic news. Overall, the coverage of Le Figaro is more favorable, or more neutral, than that of Le Monde, but both use primarily a populist radical right frame.

The most interesting finding with regard to gender bias is that the French conservative newspaper Le Figaro stands out in using a stronger gender frame than the liberal Le Monde, but the conservative Wall Street Journal does not have a stronger gender frame than the liberal New York Times. There are three potential explanations for this difference. First, U.S. newspapers use less gendered framing in their political coverage. This has been proven wrong in several earlier studies (e.g. Falk Reference Falk2010; Kittlison and Fridkin Reference Kittislon and Fridkin2008). Second, U.S. newspapers do not employ gendered frames in coverage of far-right politics. Again, studies on the coverage of, most notably, Sarah Palin show that this is not the case (e.g., Meeks Reference Meeks2012; Wasburn and Wasburn Reference Wasburn and Wasburn2011). Third, a gender frame is less prominent in the more shallow coverage of foreign news. As far as we know, this has never been researched more broadly.

CONCLUSION

All female political leaders must navigate well-established public prejudices and stereotyping, not just in politics but also in the media. Gender is a more salient feature of the coverage of female politicians than of their male counterparts, “not only because of the relative scarcity of women in such positions, but also because of the incongruence between cultural stereotypes of women and politicians” (Hall and Donaghue Reference Hall and Donaghue2013, 636). Women in politics thus find themselves in a double bind—when they try to perform “masculine” styles of leadership, they could be perceived as too aggressive, while if they are perceived as (too) feminine, they might be considered unsuited for political leadership. In both cases, they face potential punishment at the polls (Jamieson Reference Jamieson1995).

While women are even more underrepresented in right-wing parties, although not as much as is often assumed, those in leadership positions “have captured significant media attention and given right-wing politics a female face” (Schreiber Reference Schreiber2008, 23). Gender and politics scholars have started to devote more attention to the heterogeneity of women as political actors (Celis and Childs Reference Celis and Childs2012; Deckman Reference Deckman2016; Schreiber Reference Schreiber2008, Reference Schreiber2014). But while many studies have shown the existence of gender bias in the coverage of female politicians across the Western world, none have as yet analyzed the coverage of female politicians of the populist radical right.

Female populist radical right politicians such as Marine Le Pen, the leader of National Rally (previously the National Front) in France, have (at least) two identities that attract quite different media frames. The gender frame presents female politicians in a “soft” frame, in that it is less negative, emphasizes expressive personal traits (e.g., warmth), links to “softer” issues (e.g., welfare), stresses nonpolicy issues (e.g., marital status), and ignores professional traits and experiences (e.g., professional successes). In almost complete contrast, the populist radical right frame portrays populist radical right politicians strongly negatively, emphasizing instrumental personality traits (e.g., ambition), linking to “harder” issues (e.g., security), ignoring nonpolicy issues (e.g., appearance) as well as professional traits and experiences.

We analyzed the use of both the gender and the populist radical right frame in the coverage of Marine Le Pen in four newspapers: the French conservative Le Figaro, the French liberal Le Monde, the U.S. liberal New York Times, and the U.S. conservative Wall Street Journal. Interestingly, the different identity constructions of Marine Le Pen as a populist radical right and a female politician interact in a way that reduces traditional forms of gendered media bias. Several aspects of gender bias found in past studies of media coverage of female politicians were not found in this analysis. For example, the presence of substantial descriptions of her physical appearance is part of only a minority of articles in all four newspapers.

Interestingly, while the New York Times is in line with the other newspapers in terms of the percentage of references to physical descriptions, they are different in nature from those of the other newspapers. The newspaper usually uses the description of her “looks” to support their argument that the party has “softened” its presence. Her appearance, described as much more appealing to the public than that of her father, FN founder Jean-Marie Le Pen, is almost always included in a discussion of liberalization.

Gendered framing was also not particularly strong with regard to the other four features analyzed. Expressive personality traits are mentioned rarely, and much less so than more “masculine” instrumental traits. Similarly, professional accomplishments and experiences are mentioned in the vast majority of articles across all four newspapers. While Marine Le Pen is relatively often linked to “softer” issues such as health and welfare, she is much more linked to “harder” issues such as immigration and security.

In short, the overall news coverage was relatively light on the gender frame and heavy on the populist radical right frame. This holds for the coverage in all four newspapers, irrespective whether they were from France or the United States or had a conservative or liberal slant. The only difference was in terms of tone of coverage, which was overwhelmingly negative in the liberal and predominantly neutral in the conservative newspapers. The only newspaper to use a somewhat stronger gender frame, Le Figaro, also provided the most positive, or perhaps better neutral, coverage of Marine Le Pen and the FN.

Although the choices of all female politicians are shaped and constrained by the often biased norms of the political and media environment, it is important to point out that female candidates are agentic in their own campaign choices and rhetorical styles and have the potential to purposefully contribute to the formation of certain metaphors and stereotypes. Female politicians, including populist radical right female leaders like Marine Le Pen, can be active in constructing images that attempt to straddle the double bind (Meret, Siim, and Pingaud Reference Meret, Siim, Pingaud, Lazardis and Campani2016). With the increasing mediatization of politics, and the rise of celebrity politics, contemporary politicians are surrounded by communication advisers whose savvy lays in branding their politician for further reach in traditional and nontraditional media (Campus Reference Campus2017; Street Reference Street, Corner and Pels2003, Reference Street2004).

Clearly, Marine Le Pen is no exception and has politicized her gender in campaigns. For example, a 2017 New York Times article noted Marine Le Pen's “calculated,” “tactical shift” in the last months of her presidential campaign, as she strategically attempted to appeal to more female voters. It cited, in particular, an FN poster featuring the party leader in a short skirt, which aides spun as “a blow against Islamic fundamentalism, championing women's rights to dress as they choose.” Another example is a four-page electoral leaflet, whose cover featured Marine Le Pen “in a close-up head shot under the logo of the blue rose (a symbol of femininity, as she remarked during its presentation)” and internal pages displaying her with her children and sisters with headlines such as, “A woman of heart. Behind the public woman, the mother, the sister” (Campus Reference Campus2017, 153). For Marine Le Pen, this intentionally gendered representation, portraying herself as more moderate and soft, is not a liability—rather, it could be advantageous (Geva Reference Geva2018; Matonti Reference Matonti2017).

As more women take leadership positions in right-wing parties, gender and politics scholars must continue to expand the focus of their analyses to conservative and populist radical right women (see Celis and Childs Reference Celis and Childs2012). Scholars should also seek to highlight and understand the differences between media coverage of mainstream conservative women leaders and populist radical right women leaders. For example, previous research on the 2008 vice presidential run of Sarah Palin in the United States has noted the particularly blatant sexism displayed in her media coverage. Palin was frequently objectified in the media with lengthy descriptions of her beauty queen pageant background, her youthful appearance, her wardrobe, and her “unabashed feminine nonverbal communication such as winking” (Carlin and Winfrey Reference Carlin and Winfrey2009, 330). This is very different from what we find in our analysis of the media coverage of Marine Le Pen, where this “trivialization effect” was not present (Stevens Reference Stevens and Helms2012).

There are various possible explanations for this difference. First, there could be national differences between coverage in France and the United States. This seems less convincing, as previous studies have noted sexist coverage of other French female politicians (e.g., Ségolène Royal), and we included two U.S. newspapers. Second, this could be explained by the politicians themselves—that is, by the way they and their campaign teams presented the candidate. Agency seems to play a role here, as Palin played into many sexist stereotypes—including describing herself as a “grizzly mom” or “hockey mom” and developing her trademark “wink”—whereas Marine Le Pen presented first and foremost a gender-neutral image, competent and serious, only more recently emphasizing her role as mother. Finally, and most importantly, Palin was a candidate for one of the mainstream parties, even if she was portrayed as on the fringes, while Le Pen is unashamedly outside, and even against, the mainstream. Consequently, whereas Palin faced an (extreme) gender frame, only Le Pen had an intersectional gender-populist radical right media frame.

We want to end our article with three reflections on the broader study of media coverage of female politicians. First, most literature on intersectionality focuses on politicians with two largely overlapping identities, notably gender and race or gender and sexuality, where the different frames tend to strengthen the overall bias. But politicians can also have crosscutting identities, leading to largely juxtaposed media frames; scholars should investigate the complexity that arises when the subject of analysis expands to include multiple dimensions of categories of social life (see McCall Reference McCall2005). In the case of female populist radical right politicians such as Marine Le Pen, the populist radical right frame is clearly much more powerful than the gender frame. Paradoxically, the combination of these two frames actually contributes to an overall less gender biased and less populist radical right biased coverage. The (strong) populist radical right frame provides Marine Le Pen with a (much) “stronger” image in the media than nonpopulist radical right female politicians, while the (weaker) gender frame leads to a (slightly) “softer” image than radical right male politicians. Ironically, this gives female populist radical right leaders more accurate media coverage than both other female leaders and other populist radical right leaders.

Second, and related, this finding has major implications for the double bind thesis. The literature attributes the double bind to all female politicians, but women are not a monolith, and their political representations are a reflection of their overlapping identities. At the very least, not all female politicians risk that the perception of their competency is weakened by an emphasis on their “feminine” characteristics or their “femininity.” As we have seen, for female politicians who face a more dominant additional frame that portrays them as (too) “hard,” their “softer” feminine side does not undermine their perceived competence and actually leads to more balanced media coverage. This again shows that female politicians have agency, and some can even turn their gender into an asset, even if they still operate within the constraints of a biased cultural and political context.

Finally, we believe that the field should not only expand its conceptualization of representations of femininity, but also that of masculinity and of intersectionality. To the extent that much of the literature methodologically dichotomizes female and male experiences and compares female-gendered frames with an empirical norm of masculine constructions of leadership, we want to problematize this binary. A masculine narrative framing should also be conceptualized explicitly as bias, rather than implicitly as the norm. More discussion of what constitutes neutral coverage is necessary in the gender and politics literature to ensure that “male” is not equated, either implicitly or unconsciously, with the norm.

Figure 1. Gender versus populist radical right frame, New York Times

Figure 2. Gender versus populist radical right frame, Wall Street Journal

Figure 3. Gender versus populist radical right frame, Le Monde

Figure 4. Gender versus populist radical right frame, Le Figaro