As many have experienced firsthand, having children is one of the most life altering of experiences. The addition of a costly and emotionally demanding, if not ultimately loving and wonderful, dependent to a family assuredly changes the outlook of both parents in many ways. In addition to the emotional and psychological changes parenthood brings, there are the day-to-day changes dealing with day-care issues, tighter finances, worries about the quality of schools, and less free time. All these factors undoubtedly end up changing how parents look at many facets of daily life. Politics should be no different. The presence of children in one's household should cause parents to view a variety of political issues in new and different ways. Despite widespread recognition that family is one of the strongest agents of political socialization (Campbell et al. 1960; Jennings and Stoker 2000), few political scientists have explored systematically the impact that having children has on political views. The idea that being a parent has a significant political influence on attitudes has been assumed in discussions about “soccer moms” and “Nascar dads”1

For two examples, see Liz Clarke, “In the Sun Belt, Politicians Vie for NASCAR Dads,” Washington Post, August 2, 2003, sec. A1, and Ron Brownstein, “Campaign 2000; Education Surfacing as Key Issue for Bush,” Los Angeles Times, March 24, 2000. See also Clark and Clark 1999.

In this article, we explore whether having a child affects public opinion on social welfare policy, whether the effect of parenthood differs for men and women, and whether that impact has varied over time. In brief, our findings show that having children not only has a significant effect but also affects the views of men and women differently. Women with children under 18 in the home were significantly more liberal on social welfare issues than women without children. For men, the presence of children has no impact at minimum and may have induced greater conservatism in recent years. We also found that the impact of children has grown stronger over time. We argue that the increasing impact of children, as well as the increasingly divergent impact of children on women and men, is the product of two related forces: the changing nature of the American family, particularly the role of mothers, and its politicization. Over the past two decades, the major parties and the media have markedly increased the attention they have given to “family issues,” which in turn has increasingly primed parents to use their familial roles in forming political opinions.

The discovery of the “children gap” on social welfare policy and its increasingly pronounced impact over the past two decades add to a fairly new dimension of public opinion research, the political impact of parenthood. Moreover, this research holds important implications for our understanding of the gender gap. Research has shown that men and women have grown further apart on social welfare issues over the past several decades (Kaufmann and Petrocik 1999; Shapiro and Mahajan 1986). Our findings indicate that having children magnifies this trend. Moreover, our findings highlight the need for future research into the causes of the gender gap to include parental status in their analyses. At the broadest level, our findings underscore the idea that the personal is indeed political. The choices Americans make in their private lives, such as whether or not to have children, have political consequences.

POLITICAL SOCIALIZATION AND THE IMPACT OF CHILDREN

A growing number of studies have shown that the socialization process can occur across the life span and that adult attitudes are capable of significant change as a result of experiences such as entering the workforce or getting married (Andersen and Cook 1985; Jennings and Stoker 2000; Manza and Brooks 1998). Surprisingly, though, there has been minimal research conducted on one of the most critical and life-impacting experiences of many adults: having and raising children.

Intuitively, it seems that having children and the inherent responsibilities, lifestyle changes, and new roles that raising children brings about have the potential to instigate change in people's worldview and political attitudes. Indeed, one vein of feminist literature posits that women's role as mother lies at the root of their more compassionate views (Ruddick 1980; Sapiro 1982). Other work has attempted to explore the political impact of parenthood empirically, finding that parents, particularly mothers, were more likely to participate in political activities related to children's and education issues (Jennings 1979; Schlozman et al. 1995) and that having children slightly depresses the participation and political ambitions of mothers more so than fathers (Sapiro 1982, 1999). Suggesting the intriguing possibility that perhaps parenting has a conservatizing impact, Laura Arnold and Herbert Weisberg (1996) found that married parents of young children were more likely to have voted for George H. W. Bush than Bill Clinton, even when other variables were controlled.

The most relevant finding for this study comes from Susan Howell and Christine Day's (2000) analysis of the factors contributing to the gender gap across a broad spectrum of issues, including social welfare, using 1996 National Election Study data. Their conclusion was that the gender gap is complex, and that social, economic and psychological factors have differing levels of impact on women and men on different issues. They briefly mention that having children produces a particularly pronounced gender gap on social welfare attitudes. In our study, we explicitly build on this finding by more comprehensively exploring the impact of children on the social welfare attitudes of their parents and attempt to unearth the reasons why such a gap has emerged and grown larger.

Attitudes on social welfare are particularly important to examine, for several reasons. First, previous studies have documented that the primary gap in public opinion between women and men occurs on social welfare issues, with men being less supportive of government involvement and spending than women (Andersen 1998; Shapiro and Mahajan 1986). It is therefore important to investigate what role children play in enlarging, minimizing, or complicating this gap. Second, there is widespread agreement that issue attitudes are among the important variables explaining gender differences in voting behavior, with social welfare issues playing a particularly important role (Clark and Clark 1999; Kaufmann and Petrocik 1999; Mattei and Mattei 1998). By isolating the impact of children on social welfare attitudes, we contribute to a fuller understanding of the outcome of presidential and congressional races. Finally, since the 1930s, social welfare issues have remained at the heart of partisan divisions in the United States. Before the terrorist attacks of September 2001, the major parties had been increasingly integrating family policies and pro-family rhetoric into this role of government cleavage. By empirically examining the politicization of the family, this article adds new insights into the evolving cleavages and structure of American politics.

EXPECTATIONS FOR THE IMPACT OF CHILDREN ON PARENTS' SOCIAL WELFARE ATTITUDES

Although having children introduces major change into the lives of both mothers and fathers, we expect having children to have a greater impact on the social welfare attitudes of women. Although many things have changed within American families, women continue to take on a disproportionately high share of the child-rearing and child-care responsibilities (Aldous, Mulligan, and Bjarnason 1998; Burns, Schlozman, and Verba 1997; Spain and Bianchi 1996) and remain more involved in their children's lives (Harris and Morgan 1991). One reason is that many women choose motherhood as a career; nonetheless, research has shown that even when both parents work outside the home, children remain primarily the wife's responsibility (Barnett and Shen 1997; Brines 1994; Gerson 1993; Hayghe and Bianchi 1994).

Not only do we expect children to have a greater impact on women, but we also expect that the presence of children will have a liberalizing impact on women's social welfare attitudes. Having children may make women more aware of the positive role that government social welfare programs play in their lives. Arguably, women with children have a greater interest in better public school education, more expansive health care, public funding for day care, and, overall, a more active government than do women without children. This is particularly true for single mothers, mothers who live below the poverty line, and working mothers, since they need to rely on someone or something else to manage all their children's caregiving. Second, mothers, whether employed or not, are expected to nurture their children emotionally and physically to a greater extent than are fathers (Chodorow 1979; Risman 1998; Sapiro 1983, 1999). According to some, the caretaking and nurturing experiences associated with having and raising children foster greater support for an active government and progressive social welfare and economic policies (Klein 1984; Smeal 1984; Welch and Hibbing 1992).

We also hypothesize that changes in the shape of the American family over the past two decades have heightened the liberalizing impact of children on women's political attitudes. Census results show that birth rates have been dropping and are now below the national average among the highly educated and the wealthy. Parents have become increasingly likely to be struggling economically and in need of government social welfare programs (Bachu and O'Connell 2001). Second, more and more women have been raising children on their own (Amott and Matthaei 1996; Spain and Bianchi 1996). According to the 2000 census results, single parents now maintain 31% of family households with children under 18, and women constitute the vast majority of these single parents (Fields and Casper 2001). Raising children alone may intensify the parenthood experience, leading to greater parenthood effects. Additionally, a disproportionately high number of these single-parent families are living under the poverty level, heightening the need for support from the government (Fields and Casper 2001). Another significant change to the American family is that mothers, both single and married, are more likely to be working now than ever before.2

Robert Pear, “Far More Single Mothers Are Taking Jobs,” New York Times, November 5, 2000, sec. 1, 28.

The expectations about men's response to having and raising children are not as clear. Existing studies have shown that having children has relatively little impact on men's sense of identity, their occupations, their interests, and their political pursuits (Sapiro 1982, 1999). Sociological research has consistently shown that men are significantly less involved with their children than are women, although several studies show men that are slightly more involved when at least one of their children is a boy (Aldous, Mulligan, and Bjarnason 1998; Harris and Morgan 1991). Since men play a lesser role in the child-rearing process—and are expected by society to play a smaller role (Risman 1998)—we would expect having children to have less impact on men overall. In addition, since fathers are expected to be economic providers more than nurturers (Burns, Schlozman, and Verba 1997; Risman 1998), fathers may view active government and generous social welfare policies as an intrusion of big, tax-and-spend government on their ability to provide economically for their children.

THE POLITICIZATION OF THE AMERICAN FAMILY

We expect the impact of parenthood to have become a stronger determinant of social welfare attitudes over time, not only due to changes in the American family highlighted here but also due to the increasing politicization of the American family. Content analyses of media coverage, speeches, and advertisements demonstrate that during the 1980s and 1990s, both parties and the media heavily emphasized the family and family-friendly themes (Carroll 1999; Jamieson, Falk, and Sherr 1999; Plutzer and McBurnett 1991; Weisberg and Kelly 1997).

To assess the extent to which politicians, the parties, and the media have focused on family and children in their rhetoric and political stories, we conducted a systematic content analysis of two major newspapers with national political coverage, the New York Times and the Washington Post, across the 1984–2000 time period. We chose these two newspapers because 1) they have the most extensive coverage of national political affairs, and 2) they are the only major national newspapers fully archived on Lexis/Nexis over this entire time period. We examined New York Times and Washington Post articles for the calendar year of each of the five presidential election years in our analysis. We searched to see how often the key words “children” or “family” were found in the lead paragraph of stories along with “Republican” or “Democrat.” For control purposes, we also conducted parallel searches for key words, including “social security” and “military spending.”

We found that the attention of the parties to issues of children and family increased fairly dramatically over the time period. As Table 1 shows, and Figure 1 depicts graphically, family and children have received increasingly more attention in political stories over the past two decades. In 1984, the New York Times contained 228 political stories (mentioning Democrat or Republican) that mentioned “family” or “children,” and by 1992 that number had increased to 601. The number of stories focused on family and children actually peaked in 1996 with 1127, which is in keeping with the arguments of Susan Carroll (1999) and Kathleen Hall Jamieson, Erika Falk, and Susan Sherr (1999). In the year 2000, the number of political stories focusing on family and children declined from the 1996 high, but remained well above the numbers from the 1980s. The results from the Washington Post almost perfectly mirror those of the Times, but with smaller overall numbers. The over-time nature of the analysis essentially controls for other factors that may be contributing to the number of stories we found (i.e., the presence of stories about the candidate's families and children). Moreover, the results of searches with alternative terms, such as “military spending” and “social security,” did not show a similar increasing pattern. Because issues concerning family policy have been gaining center stage, and a variety of political issues from across the spectrum have been increasingly presented in terms of their impact on the family, we expect to find that the politicizing impact of having children will grow over time.

Mentions of “Democrat” or “Republican” with “family” or “children” in the New York Times and Washington Post, 1984–2000.

Frequency of partisan-oriented family/children stories in the New York Times and the Washington Post, 1984–2000

It is important to note that although the expanded use of the family frame has been bipartisan, the direction of the message coming from the two parties has been different. Republican candidates have emphasized the importance of minimalist government as the best way to support and strengthen the traditional American family. In 1992, Republican vice presidential candidate Dan Quayle said, “We think lower taxes strengthen families.”3

E. J. Dionne, Jr., and Saundra Torry, “Quayle Recasts ‘Family Values' in Terms of Domestic Policy; Vice President Says Democrats’ Approach Differs,” Washington Post, August 28, 1992, sec. A18.

David E. Rosenbaum, “The Nation; In a Debate, It's Themes, Not Facts,” New York Times, October 13, 1996, sec. 4, 4.

John F. Harris, “Clinton Pulls Punches; Ads Land Them; TV Spot Hits Dole on Family Leave as President Pitches Welfare Overhaul,” Washington Post, September 11, 1996, sec. A10.

Maralee Schwartz, “Clinton Proposes 6-Point Program to Aid Families; Candidate Faults Both GOP, Democrats on ‘Family Values,’ ” Washington Post, May 22, 1992, A20.

DATA AND METHODS

We examined the impact of children on public opinion using five presidential election year National Election Studies: 2000, 1996, 1992, 1988, and 1984. We explored the issue longitudinally to see if the impact of children has changed as the gender gap has grown in recent years (Chaney, Alvarez, and Nagler 1998; Pigg and Elder 1997). These NES studies naturally contain a wealth of data on public opinion on major issues, including social welfare policy. Importantly for present purposes, all these NES data sets also determine whether or not there are children under 18 living in the interviewed household. In addition to issue positions on social welfare policies, the presence of children in the home, and gender, we include a variety of demographic and attitudinal variables to serve as controls in multivariate analyses. With a few minor exceptions to be noted, the question wording and coding for each variable are the same for each NES.

Our analyses are rather straightforward. We compare the mean scores on an index of social welfare attitudes for women, with and without children at home, and for men, with and without children at home, in 1984, 1988, 1992, 1996, and 2000. Then, in order to determine the independent impact of children, we use social welfare attitudes as the dependent variable in which children at home is the key independent variable and other demographic and attitudinal variables serve as controls. Since not only parenthood but also other social and demographic variables (e.g., education, marital status, age) may differentially affect the social welfare attitudes of women and men, we follow the logic laid forth in Nancy Burns, Kay Lehman Schlozman, and Sidney Verba's 2001 study (pp. 48–50) and estimate these models separately for men and women in each election year. The advantage of this approach is that it rejects the unwarranted assumption that men's and women's experiences affect their social welfare attitudes in the same ways, and thus allows each independent variable to take on different values for each sex. Our final analysis (presented in Table 4) focuses specifically on the 2000 data. In this analysis, we compare the mean scores on our complete social welfare index of dads versus non-dads and moms and non-moms within various demographic segments of the population. These comparisons provide insight into how parenthood effects interact with demographic factors that our hypotheses indicate are significant, such as income, marital status, and employment.

2000 Social welfare attitudes by gender and children

Variables

The dependent variable in all of our analyses is an index of attitudes toward government social welfare policy. We use a truncated version of the social welfare index featured in Howell and Day (2000). We originally created an index using respondents' self-placement on seven-point scales for the issues of government spending and services, guaranteed job/standard of living, and government involvement in health care, along with all relevant spending items available for each year from among the following: spending on social security, food stamps, public schools, student aid, the homeless, child care, and poor people. In order to have true comparability over the years 1984 to 2000, however, our final index includes only the variables that appear in all five of these data sets—the three seven-point measures, along with spending on social security, food stamps, and public schools. The issues were coded such that higher numbers indicated more liberal positions. In keeping with Howell and Day, each variable was standardized and the index is the mean of these standardized values. For our analyses strictly limited to the year 2000, we used all available data; therefore, our policy index additionally includes the items for spending on welfare, aid to poor, and child care. (Complete descriptions of variables and their coding are available in the appendix.)

Our independent variables can be grouped into three general categories: basic demographics, employment type and status, and attitudes and values. Demographic variables used include household income, age, marital status (married vs. not married), race (white vs. nonwhite), education (highest level completed), and children in the household.7

Although many studies addressing gender gaps restrict the sample to white persons only, we believe that in this study it is most appropriate to include persons of all races. Though minorities will likely start from a more liberal baseline, in many ways having children should have a universal impact, regardless of one's race or ethnicity. Furthermore, when we do conduct analyses on whites only, the results are essentially unchanged.

We include five measures of values and attitudes. Given the pervasiveness of the gender gap in partisanship (e.g., Andersen 1998; Kaufmann and Petrocik 1999), a party identification control variable is included. As surveys have shown that women are more religious than men (Conover 1988; Cook and Wilcox 1991), we include a variable for religious importance. We also include NES indices of both traditional values and egalitarian values. Finally, we include feminist values using an adjusted feeling thermometer toward the women's movement. Since women and men may vary along many of these factors, as well as having children at home, the inclusion of all of these additional factors in a multivariate analysis allows us to determine the independent impact of children on public opinion.

THE GROWING CHILDREN GAP AND THE POLITICIZATION OF AMERICAN PARENTS

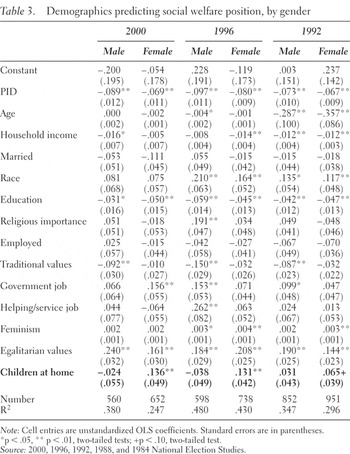

Our first significant findings are that having children does impact the social welfare attitudes of their parents and that this impact is gendered. The effect of children was the most pronounced among women, which fits our expectations since, in the aggregate, children play a much greater role in the lives of their female parents than their male parents. The bivariate comparisons in Table 2 show that women with children under 18 are significantly more liberal than their childless counterparts in every presidential election year from 1984 through 2000. The multivariate analyses in Table 3 demonstrate that even with a thorough set of controls, having children in the household predicts more liberal social welfare attitudes among mothers from 1992 to 2000.8

Although the statistical significance of the children-at-home variable for women is only p < .10 for 1992, we are confident of this result, given that the statistical significance is below p < .05 when using the full index comprising all the available social welfare items in the 1992 data set.

Mean position on social welfare issues by gender and children, 1984–2000

Demographics predicting social welfare position, by gender

Continued.

Our analyses as presented in Tables 2 and 3 also show intriguing trends. The overall impact of having children has been growing, and it appears to be pushing women and men further apart in terms of their attitudes on social welfare policy. Thus, the presence of children reinforces the growing gender gap on social welfare issues noted by others (Kaufmann and Petrocik 1999; Shapiro and Mahajan 1986). We argue that these results are the product of two interrelated processes: the changing American family combined with the “politicization of the family” discussed previously. Over the past two decades (until 9/11), the political debate has moved away from international concerns and has focused more on issues concerning the family—from family values to health care to education. Across the 1980s and 1990s, the parties and their candidates increasingly framed issues in ways that emphasized the benefits for children and the family as illustrated in the media analysis displayed in Table 1. This increased rhetoric about the family appears to have primed parents to think about politics in terms of the family (Carroll 1999). The effect of the “politicization of the family” is perhaps most clearly shown by the correspondence between the data analyses in Table 3 and the media analysis in Table 1. When media and political attention to the family moves to and remains at a consistently higher level, so does the impact of children on the social welfare attitudes of women. There is a very large jump in political news stories about family in 1992, and this is also the first year in which the motherhood effect remains significant in multivariate models. Moreover, the coefficients for the impact of children on women increase significantly in 1996 as the attention to these issues reach an all-time high.

Not only has increased family rhetoric over the 1990s primed people to think about politics in terms of the family, but it also appears to have affected the attitudes of both fathers and mothers in distinct ways. Mothers appear to have responded to the politicization of the family by embracing the Democratic Party's liberal, pro-government message, while fathers show some indications of having shifted toward the conservative, less-government argument of the Republicans.

Women's heightened responsiveness to the Democrats' pro-government family rhetoric makes sense for two reasons. On the most basic level, women are more likely to respond to the liberal social welfare appeals of Democrats because women are a disproportionately liberal and Democratic group. Political appeals by parties are much more likely to reinforce and reinvigorate existing beliefs than to attract new converts (Ansolabehere and Iyengar 1995). Beyond the reinforcing effects of partisanship, Table 4 suggests that the Democratic message may be powerful for mothers because it resonates with the changing reality of their lives. Although, for women, having children at home was associated with more liberal social welfare attitudes across the board, Table 4 shows that the disparity in attitudes between women with and without children is greater among some demographic subgroups than it is in the full sample. The effect is the greatest among unmarried women, women of lower socioeconomic status, and women who are working, precisely the subgroups of mothers who have been increasing in number across the past several decades. In their daily routines, these subgroups of mothers are particularly likely to see firsthand the need for more government spending and services so that they and their children can have access to a good-quality public education, affordable child care, and decent health care, and rely on government programs to support and care for their children (Deitch 1988; Erie and Rein 1988; May and Stephenson 1994; Piven 1985). Additionally, the Republican message of tax cuts so that women can stay home with their children is singularly unsuited—and perhaps offensive—to single moms as well as to two-parent families struggling to stay above the poverty level with two wage earners. As the partisan rhetoric over families has heated up, mothers seem to have been increasingly compelled by the Democratic Party's message (or repelled by that of the Republicans) to embrace more liberal social welfare positions.

Meanwhile, as the parties and media ratcheted up their emphasis on family politics during the 1990s, men may have been moving toward the smaller government message of the Republicans. In the bivariate comparisons in Table 2, men with children and without are not statistically distinct at the p < .05 level in any of the five years. It is worth noting, however, that starting in 1992, the gap between fathers and non-fathers—with fathers being more conservative—grows every year, and that these differences are significant at the p < .10 level in each of these cases. Although not definitive, it appears that in recent years men, in direct contrast to women, may have begun to associate the care of children with the need for less social welfare spending and fewer programs. Since men are a more Republican group in the aggregate, it makes sense that they would be more receptive to the arguments of the Republican Party. Moreover, the message of the Republican Party about family meshes better with the role expectations and realities of male parents. A large and active government, which pursues social welfare spending at the expense of taxpayers, may be seen as an intrusion by men on their ability to support their families financially, a theme the Republican Party increasingly emphasized across the 1990s. Turning once again to Table 4, we see strong, if indirect, evidence for this argument. In 2000, having children under 18 in the home makes men overall more conservative on social welfare issues than are their childless counterparts. However, the men who are particularly pushed in a conservative direction by having children are white, highly educated men who are employed, precisely the group who seems to be the target for the GOP's family-values message.

Despite the suggestive results regarding fatherhood and social welfare attitudes in Table 2 and Table 4, the multivariate models do not support the conclusion that fatherhood makes men more conservative. In only one of the five models, 1988, does the children-at-home variable significantly impact the social welfare attitudes of men, and not in the expected direction.9

As to the interesting anomaly of 1988, we offer little in the way of explanation. A much more thorough analysis of this unique election year context is likely required to explain why 1988 is unique among men with children.

CONCLUSION

Public opinion is supposed to be the great engine of democracy, determining what government does (Page, Shapiro, and Dempsey 1987), but scholars are still far from uncovering all the factors that shape public opinion. In this article, we have examined the political impact of parenthood on adult men and women, an underresearched but potentially fruitful and significant area of study. We found that the increased politicization of the family during the past two decades has been a bipartisan phenomenon, but that the content of the two major parties' messages has acted to polarize male and female parents, creating a significant “children gap” in the American electorate.

Not only do our findings enrich our understanding of public opinion and, more specifically, the gender gap in public opinion, but to some degree they also contribute to a more thorough understanding of the gender gap in voting. Recent studies find that a considerable portion of the gender gap can be explained by the different issue positions of men and women, especially on social welfare issues (e.g., Andersen 1998; Clark and Clark 1999; Kaufmann and Petrocik 1999; Manza and Brooks 1998). Thus, while M. Kent Jennings and Laura Stoker (2000) have shown that marriage plays a role in minimizing the gender gap in policy attitudes as well as voting, having children appears to contribute to a widening of the gap since having children pushes women's attitudes in a distinctively liberal direction.

By showing that the personal is political, and that having children does shape the political views of their parents on social welfare issues, we believe that we have identified an interesting and significant area for further research. We are hopeful that future studies can reveal a fuller and more detailed picture of how having children, certainly one of the most dramatically life-changing experiences, impacts the political worldview of parents. Although this study focused on social welfare issues, we believe that where possible, further studies should explore other issue domains and political experiences where children in the household may impact the opinions of women, men, or both sexes. Moreover, we believe it is important to expand questions about parenting and children on political surveys, that is, including questions to identify the sex of children, the existence of grown children, and the level of parental involvement for respondents, so that we can develop a richer understanding of how the child-rearing experience affects political attitudes.

APPENDIX: VARIABLES AND CODING

Social Welfare Policy Index: Index of responses on issues of the seven-point scales for government spending, government guaranteed job, and government involvement in health care, along with responses to more/less government spending on food stamps, social security, and public schools. For analyses conducted for 2000 only (i.e., Table 4), the index also includes spending on welfare, aid to poor, and child care. Constituent variables are standardized and index is mean of standardized variables. Positive values indicate more liberal responses. Range: −2.98 to 1.20.

Children at home: Dummy variable scored 1 if respondent has child(ren) 18 or under living at home, 0 otherwise.

Household income: NES 24-point scale of income.

Education: NES seven-point scale indicating highest level of education.

Married: Dummy variable scored 1 if respondent is married, 0 otherwise.

Race: Dummy variable scored 1 if respondent is a minority, 0 otherwise.

Age: Age in years.

Religious importance: Scored 1 if respondent indicates that religion is an important part of life, 0 if it is not.

Employment: Scored 1 if respondent is currently employed, 0 otherwise.

Government job: Scored 1 if respondent works or has worked for the government, 0 otherwise.

Helping/service occupation: Scored 1 if respondent is in occupation geared towards helping or service to others, 0 otherwise. Examples are teacher, firefighter, nurse, and so on. Based on collapsed Census occupation codes. Unavailable in 1984 data.

Party identification: NES seven-point scale ranging from 0, Strong Democrat, to 6, Strong Republican.

Feminism: Adjusted feeling thermometer score toward “women's movement.” Similar to measures of feminism and feminist consciousness in earlier research, the thermometer score is adjusted for individual variation in the meaning of the scale by subtracting the mean of all other postelection thermometer measures (i.e., Cook 1999; Cook and Wilcox 1991; Wilcox, Sigelman, and Cook 1989).

Traditional values: Mean of response (strongly disagree to strongly agree) to series of questions about traditional values. 1–5 scale, with 5 being most traditional. Unavailable in 1984 data. Questions include “newer lifestyles are contributing to the breakdown of society”; “the world is always changing and we should adjust our moral views to those changes”; “the country would have fewer problems if there were more emphasis on traditional family ties”; and “we should be more tolerant of people who choose to live by their own moral standards.”

Egalitarian values: Mean of response (strongly disagree to strongly agree) to series of questions about egalitarian values. 1–5 scale, with 5 being most egalitarian. Questions include “Our society should do whatever is necessary to make sure that everyone has an equal opportunity to succeed”; “We have gone too far in pushing equal rights in this country”; “One of the big problems in this country is that we don't give everyone an equal chance”; “This country would be better off if we worried less about how equal people are”; and “If people were treated more equally in this country we would have many fewer problems.”