Japan is seen as an outlier among old liberal democracies in that women's political representation in the House of Representatives has stagnated at approximately 10% for almost two decades. Gender and politics scholars have pointed to strong cultural norms concerning gender roles, the masculine culture of major political parties, weak Leftist parties, lack of quotas, and time-consuming constituency service to account for this phenomenon (e.g., Dalton Reference Dalton2015; Miura, Shin, and Steele Reference Miura, Shin and Steele2018; Ogai Reference Ogai2001; Steel Reference Steel2019; Steel and Kabashima Reference Steel and Kabashima2008).

However, women's political representation in subnational legislatures in Japan, where the gender ratio ranges from zero to parity, shows more diverse trends.Footnote 1 In most local legislatures, the proportion of women began to rise from the late 1980s, and this trend accelerated in the 2000s in many municipal councils (Martin Reference Martin and Steele2019; Oyama and Kunihiro Reference Oyama and Kunihiro2010). During this period, a women's local party named Seikatsusha Nettowa-ku (Netto, hereafter)Footnote 2 appeared in urban areas and spread to several prefectures.

The first Netto organization was formed by women from middle-class backgrounds in Tokyo in the late 1970s. The neighboring prefecture of Kanagawa followed suit, organizing a similar local party with an explicit aim to send its delegates to municipal councils. By the early 1990s, the Netto party had formed in four more prefectures: Chiba, Saitama, Hokkaido, and Fukuoka. It expanded its constituency by claiming to be an alternative to conventional male-centered parties. Its candidates ran for office on the party platform of promoting local citizens’ “everyday life issues” neglected by conventional political parties.

Unlike most women's or feminist parties in other parts of the world, which are short-lived or remain between social movements and political parties, the Netto party in Japan has succeeded in winning seats for nearly four decades. Since its inception, the Netto doubled or even tripled its seats in every election until the mid 2000s, when the electoral success of the party peaked. Although some regional Netto organizations have faced difficulties in winning recent elections, the party continues to contest local elections. In 2018, the Netto boasted 105 deputies in 74 local councils in eight prefectures.Footnote 3

Previous studies on the emergence and success of the Netto party have examined the sociological background of the party members, its relation to women's co-op movements, and the strengths and limits of its urban housewife constituency in transforming gender norms (e.g., Eto Reference Eto2005; Gelb and Estevez-Abe Reference Gelb and Estevez-Abe1998; Lam Reference Lam1999; LeBlanc Reference LeBlanc1999; Ohki Reference Ohki2010; Sato, Amano, and Nasu Reference Sato, Amano and Nasu1995). However, the party's reliance on urban housewives also makes it hard to expand its constituency as more women work outside the home. Since the mid 1990s, the number of the households with a stay-at-home wife has been outstripped by that of dual income earners. Responding to these demographic and cultural changes is a significant challenge for the Netto party, since the middle-class housewife identity has shaped every aspect of the party's activities, from policy agenda to the election campaign.

Previous studies of Netto focused on its gendered nature and viewed urban housewives as core members. However, none has examined Netto as a women's party. They define Netto as one type of green party (Lam Reference Lam1999), or as a local party with bottom-up mobilization as opposed to conventional political parties with national organizations. This article redefines Netto as one type of women's party, a distinct party family that Cowell-Meyers, Evans, and Shin propose (this issue). I examine Netto’s electoral success and the challenges it faces, the aspects in which the Netto party has been different from conventional (male-centered) political parties, the challenges the party has confronted, and the ways it has coped with them (or not).

In the following sections, I first propose a definition of “women's party” using two criteria of women's descriptive and substantive representation that generate six ideal types of political parties. The ideal types can be used as an analytical tool to examine the ways in which political parties are gendered. The second section provides an overview of the electoral performance of the Netto party. The third section analyzes the Netto party as a “proactive women's party” in terms of organization, constituency, platform, and the alternative representation system it employs. The article concludes with a discussion of the electoral challenges the party confronts and the implications for the enhancement of women's political representation.

CONCEPTUALIZING WOMEN'S PARTIES: FEMINIST, PROACTIVE, OR REACTIVE?

Despite the paucity of research on women's parties, women's parties are not rare in the history of party politics, nor are they confined to the European region. Their electoral performances have also varied. Many parties were not successful in winning seats, but some parties, such as the Northern Ireland Women's Coalition and Women of Russia, have won national seats (Cowell-Meyers Reference Cowell-Meyers2014; Ishiyama Reference Ishiyama2003).

Although almost all of the women's parties have been short-lived, new ones have continued to appear. In 2014, Sweden's Feminist Initiative won its first seat in the European Parliament eight years after its inception. In the United Kingdom, the Women's Equality Party was formed in 2015, and it has fielded multiple candidates in local elections (Evans and Kenny, this issue), and The Feminist Party was formed in Finland as recently as 2016.

Despite such recurrence, it is not always obvious which party qualifies as a women's party or how a women's party is different from or similar to a feminist party. If a party claims to be a “women's party,” is that sufficient for it to qualify as a women's party? Conversely, is a party a women's party if women run the party and all candidates are women, but the party does not identify itself as a women's party? A feminist party seems to be more self-evident because of its members’ feminist identities, the party's name, and a clear platform. However, not all parties formed by women utilize feminist platforms. Notably, the Netto party does not identify itself as a “women's party,” let alone a feminist party, even though almost all of the candidates and deputies have been women.

The Netto party challenges the assumption that all women's parties seek to promote feminist platforms. It calls for theoretical elaboration by which women's parties can be classified into conceptually clearer categories. Gender and politics scholars contend that women's parties are distinct parties of or for women whose central and defining purpose is to increase women's political representation (Cowell-Meyers 2016; also see Cowell-Meyers, Evans, and Shin, this issue). To make this definition more specific, I propose to define a women's party by its membership, leadership, candidacy, and platform: a women's party is a political organization, most of whose members are women, that is run by women's leadership and that fields women candidates to run for office on women's practical or feminist platforms. These four elements could create different types of women's parties. Applying the concepts of women's descriptive and substantive representation in politics to these four aspects of the definition of women's parties, this article derives a typology of women's parties.

First, the level of descriptive representation of women indicates whether women constitute a majority of members, candidates, and the party's leadership. These factors divide parties into two groups: “women dominated” and “women mobilized.” Women-mobilized parties are characteristic of most conventional parties, in which women join as rank-and-file members, volunteers in election campaigns, and mobilized voters, yet they remain a minority in party leadership positions. Modern political parties are open and inclusive when it comes to membership. Women are encouraged to join the parties, but women are seen primarily as vote mobilizers rather than as agenda setters and party leaders. The Japanese Communist Party and Komei party fall into this category.

Women-dominated parties, on the other hand, are parties run by female leadership. Women comprise the bulk of party candidates. These parties are grounded on the gendered identity of the members and leaders. They typically use “women,” “mother,” or “feminist” in their party names. Although women can be a majority in both types of parties, it would be valid to suggest that only those parties where women are the majority in all three aspects—membership, candidacy, and leadership—would qualify as women's parties.

The second criterion is women's substantive representation within political parties. Molyneux proposed widely used concepts such as women's “practical interests” and “strategic gender interests” (Molyneux Reference Molyneux1985, Reference Molyneux1988). She conceptualized women's practical interests as seeking satisfaction of those needs arising from their specific location and responsibilities within the sexual division of labor. Women's immediate needs as caretakers of their families, such as maintaining access to safe food or clean water, exemplify this category. On the other hand, strategic gender interests claim to transform social relations that underpin women's subordination, for example, abolition of the sexual division of labor, removal of institutionalized forms of discrimination, establishment of freedom of choice over childbearing, and the adoption of measures preventing male violence and control over women (Molyneux Reference Molyneux1985, 233).

Alvarez (Reference Alvarez1990, 25) extended these concepts of women's practical and strategic gender interests to distinguish “feminine” from “feminist” organizations. Alvarez argued that feminine organizations mobilize to defend women's rights as they are defined by the dominant culture, whereas feminist organizations challenge socially ascribed sex roles on the basis of strategic gender interests. In this formulation, feminist organizations focus primarily on challenging the conventional gender hierarchy, a goal that often puts them in opposition to feminine organizations.

I build on this work to conceptualize women's parties, distinguishing “proactive women's parties” (practical interests, feminine organization) from “feminist parties” (strategic gender interests, feminist organization). For example, the French women's local party Femmes d'Alsace can be defined as a proactive women's party (Murakami Reference Murakami2017), whereas new women's parties that have emerged in Europe such as the Feminist Initiative and Women's Equality Party are typical examples of feminist parties.

To these I add a third category of “reactive women's party” to incorporate antifeminist women's parties or parties with no women's concerns. A reactive women's party might be a rarity in reality. However, given the wide spectrum of women's concerns and actually existing conservative women's organizations, an explicitly antifeminist party formed by a conservative women's group is theoretically and realistically plausible. It is important to recognize women's political agency regardless of what they promote.

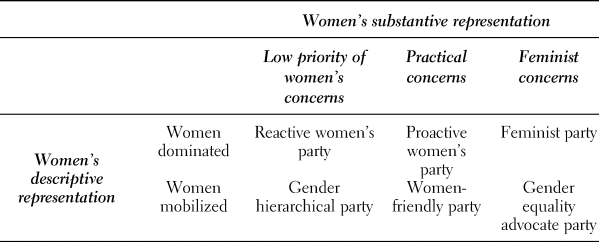

In Table 1, political parties can be classified into six different types defined by the combination of women's descriptive (membership, candidates, leadership) and substantive representation (party platform) within the party. The first row represents three substantively different types of women's parties as defined by the priority of women's concerns in party platforms: reactive, proactive, and feminist. Among parties in which women comprise a simple majority of members or are seen as party voters (i.e., women-mobilized parties in the second row), women's concerns can also be represented within parties to various degrees. For example, parties on the Left and Green parties are often strong supporters of women's policy issues. Those parties can be classified as “women friendly” or “gender equality advocate parties,” but they do not qualify as “women's parties.”

Table 1. Conceptualization of parties by women's substantive and descriptive representation within parties.

These concepts provide an analytical framework to better understand a variety of women's parties. Notably, what constitutes women's practical or feminist concerns is highly contingent on the cultural meaning of particular issues within a given society. Concepts help better characterize women's parties on a large spectrum, but they might not always be applied neatly to existing women's parties. In real politics, women's groups of diverse ideological orientations from different parties often find themselves working in pursuit of the same policy goal.

The boundary between practical and feminist platforms may also be blurred. Just as women's activist organizations often address their constituents not only as women but also in relation to their gender roles as mothers, sisters, or wives, women's parties may also employ fluid organizational strategies and platforms. The process of organizing and participating in women's parties can be seen as a part of mobilizing women to “bring women into political activities, empower women to challenge limitations on their roles and lives, and create networks among women that enhance women's ability to recognize existing gender relations as oppressive and in need of change” (Ferree and Mueller Reference Ferree, Mueller, Snow, Soule and Kriesi2004, 577).

This view is particularly salient in Japan, where women's mobilizations based on culturally ascribed gender roles as housewives and mothers have been very persistent (Eto Reference Eto2005; Shin Reference Shin and Gaunder2011). Although these women's mobilizations have not been identified with the women's movement, they have contributed to the large-scale mobilization of ordinary women into action. Feminists have been rather critical of mobilizations grounded in the role of mother and housewife, given that they have further reinforced, rather than challenged, the inequalities underpinning gender relations in Japanese society (Kanai Reference Kanai1992). However, women's activism based on traditional women's roles is not always opposed to feminist goals. This inclusive understanding of women's activisms suggests that more elaborate categories of women's parties can help capture the dynamic complexities of women's political activism that spans a broader range of issues than is recognized by the conventional definition of the feminist party.

This discussion helps to charaterize the Netto party as a “proactive women's party,” distinct from both feminist and reactionary women's parties but still included in the definition of women's party.

THE ELECTORAL PERFORMANCE OF NETTO

Netto is distinct from women's parties in other regions of the world. Cowell-Meyers (Reference Cowell-Meyers2014) argues that women's parties have a short life cycle and that their strategies are more typical of a social movement than of a political party because many women's parties emerged from social movement organizations to push for particular goals in politics. The purpose of these movement parties is not so much electoral success but increasing women's representation and access to politics.

In contrast, the Netto is exceptional in its practical goals, impressive electoral performance, and long duration. Although it is also a movement party in the sense that it grew out of a successful women's co-op movement, the party has established itself as a separate local party with an explicit electoral platform. It has succeeded in electing candidates to local assemblies for nearly 40 years. Table 2 displays the electoral performance of the Netto since 1979 in the Tokyo metropolitan area, the first regional Netto organization. From the election of the first deputy in 1979, the number of Netto deputies increased dramatically until the early 2000s.

Table 2. The number of the Netto deputy in Tokyo metropolis

Total = 207 as of February 1, 2019. The number in parentheses is the number of the Netto deputy in the Tokyo prefectural assembly.

At its peak in 2003, the Netto elected 63 deputies in special ward, city, and prefectural legislatures in Tokyo, including six members (4.7%) of the Tokyo prefectural assembly. As it grew, whether it should remain a local party or advance to higher-level legislatures became an issue of discussion. After consecutive electoral successes in local elections, some regional Nettos challenged prefectural elections. Tokyo, Kanagawa, and Chiba Nettos were successful in winning seats in the prefectural assemblies at the heart of the Tokyo metropolitan area. In the 2001 Tokyo prefectural election, Netto accomplished a surprising feat of electing all six candidates who ran for office on the Netto platform. Similar outcomes were accomplished in other regional Nettos in the 2000s. In the 2019 local election, the Netto in Saitama prefecture (also in greater Tokyo) joined this group when the first and only male deputy among 105 Netto deputies succeeded in moving up the ladder from the Kosigaya city council to the Saitama prefectural assembly.

After the mid-2000s, however, the regional Netto parties established early on began to stagnate or lose seats. In the 2011, 2015, and 2019 local elections, for example, the Tokyo Netto won 46, 42, and 36 seats.

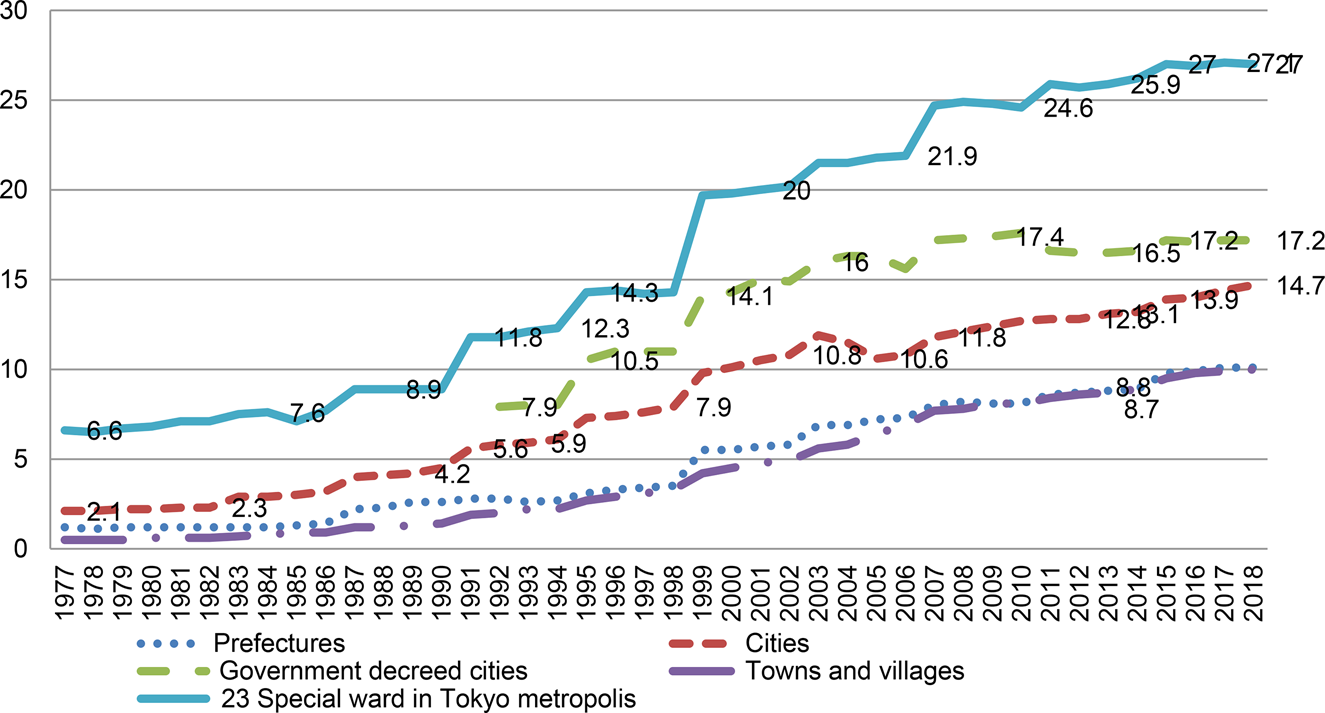

The electoral success of the Netto party until the mid-2000s coincided with a general trend in women's political representation in subnational legislatures in Japan. The top two lines in Figure 1 show sharp increases in the number of women legislators in the 23 special ward assemblies in Tokyo and in the 20 government-decreed city councils.Footnote 4 The share of women in special ward assemblies in Tokyo has exceeded 25% in recent elections without any particular institutional changes or revisions to the electoral law.

Figure 1. Women legislators in local assemblies in Japan (1977–2018, %). Source: White paper on Gender Equality, 2019. The Cabinet Office of Japan, Gender Equality Bureau.

One reason for the electoral success of the Netto party is that it tapped into the urban networks of nonpartisan women. The biggest Netto support base is socially conscious housewives in Tokyo and other large cities. Many of them had work experience in professional jobs before quitting paid work to marry or give birth. Often, they had to move to other cities following their husbands’ job transfers.Footnote 5 The Netto party became a local venue for passionate and savvy middle-class women to participate in public activities.

Another reason for the expansion of the Netto party in cities is the local electoral system. Previous studies have found a positive relationship between large district magnitude (i.e., a large number of seats per district) and female electoral success (Martin Reference Martin and Steele2019; Matland Reference Matland and Karam2002). Japan uses single nontransferable vote (SNTV) multimember district systems for special ward, town, and village councils. In some councils, all members run in a single district. For elections to assemblies in prefectures and government-decreed cities (those with populations exceeding 500,000), legislators are elected through an SNTV system from multiple districts but with smaller district magnitudes. With the SNTV electoral system, especially where district magnitudes are large, local elections are much more open to small parties and independents than national elections to the House of Representatives, where two-thirds of legislators are elected in single-seat districts. The local election system enables a small niche party like Netto to elect its candidates with a relatively small numbers of votes. The special wards in Tokyo each have one large district with 25–50 seats, enabling Netto candidates to win by acquiring as few as several hundred votes.Footnote 6

The success of Netto has inspired other parties to field more women in local elections in urban areas, with mixed impacts on Netto’s electoral performance. Although the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), Japan's long-time ruling party (except for 2009–2012 under the Democratic Party of Japan), has always been passive about recruiting women candidates, minor parties have become more proactive in fielding women candidates in local elections. In particular, the Japanese Communist Party and the Komei Party are leaders in fielding women candidates because they are “women-mobilized parties” in which women comprise a large portion of both the rank and file and candidates for local elections.Footnote 7 In addition, new women-mobilized parties continue to rise and fall in local elections.

These parties often adopt similar platforms and field women candidates to appeal to urban mothers and citizens with antiestablishment sentiments. For instance, Netto lost two of three seats in the 2017 Tokyo metropolitan election when the new Tomin First No Kai under the leadership of the first woman Tokyo governor Yuriko Koike won an overwhelming victory.Footnote 8

THE NETTO PARTY AS A “PROACTIVE WOMEN'S PARTY”

Although Netto was often criticized for having male leadership in its early days, all of my interviewees confirmed that Netto is run by women members.Footnote 9 So far, all Netto deputies elected to local assemblies have been women except for one male deputy in Saitama prefecture. Netto recruits women candidates to run on its platform, and it carries out the entire election campaign with the labor of women volunteers. From the perspective of women's descriptive representation, Netto is a political party in which women dominate the organization in all three criteria: membership, leadership, and candidacy.

However, members of the Netto do not perceive their party as a “women's party,” let alone a feminist party, and the party has not featured women's representation or women's rights issues on its platform (Gelb and Estevez-Abe Reference Gelb and Estevez-Abe1998). These characteristics distinguish Netto from feminist parties and make it a prototype of a proactive women's party.

Organization

Previous studies have shown that women's parties tend to arise when there is already an established tradition of separate political or social organizations for women (Cowell-Meyers Reference Cowell-Meyers2014; Ishimaya Reference Ishiyama2003; Stevens 2007). Netto is also based on an existing women's network, the Seikatsu Kurabu Seikyo (hereafter, the Life Club Co-op or the Co-op), composed overwhelmingly of urban housewives.Footnote 10Netto was founded as a political organization legally separate from the Life Club Co-op with the purpose of sending local co-op deputies directly to municipal councils. This movement was called the “Dairinin (deputy) movement” and was first proposed in 1977 by the organizer of the Life Club Co-op, a former Socialist party activist named Kunio Iwane.Footnote 11 The movement succeeded in electing its first deputy in the 1979 local elections in Tokyo's Nerima ward.

The Life Club Co-op provided the social and ideological base for the Netto’s deputy movement (Amano Reference Amano and Stickland2011; Ogai Reference Ogai2005). The Life Club Co-op began in 1965 in Tokyo's Setagaya ward when a group of housewives under Iwane's leadership created a milk-purchasing cooperative. The Co-op established a unique organization and delivery system with a local unit called han, to which all members in a neighborhood belonged. Each han placed a collective milk order directly with the producers to secure quality products at lower prices by bypassing middlemen. Life Club Co-op quickly grew to hundreds of thousands of members. Most activities were carried out voluntarily by women in each han, including the coordination of orders and arrangement of deliveries.

The Life Club Co-op originated as a response to housewives’ concerns about the harmful effects of industrialization on food safety and the environment. As participants increased, local units of the Life Club Co-op expanded their activities. Moving beyond the initial practical interests, they aimed at the broader goal of establishing an alternative society based on cooperative local communities. Participation in those activities assured women of the relationship between their activities as consumers and larger social problems, such as environmental destruction. Against the backdrop of critiques of the harmful outcomes of capitalism and industrial development, which to them were men's work, women appreciated their wifely and motherly roles as careful consumers, and their unique ability to propose and develop an alternative way of life and engagement with nature (Amano Reference Amano and Stickland2011).

As women came to understand how municipal policies influenced their communities, Co-op members submitted formal petitions and appeals to the local administration to change policies about garbage, chemical detergents, and school food programs. But their petitions were not taken seriously. Such frustrating rejections motivated the Life Club Co-op activists to establish political organizations to send their own deputies to the municipal councils (Igarashi and Schreurs Reference Igarashi and Schreurs2012).

The initial form of the Netto party was a political organization of the Co-op in each region. As the Nettos in Tokyo and neighboring Kanagawa prefecture drew wide public attention, Co-op members in various regions visited and learned from Tokyo or Kanagawa Netto members and started their own Netto parties. By the early 2000s, eight prefectural Netto party organizations had appeared; most were formed in cities. The official association, “Japan People's Political Network,” is nothing more than a loose network, with no national leadership coordinates, candidates, or policies.Footnote 12

The Life Club Co-op has been a major support base for the Netto party as well as an important pipeline for Netto candidates. Co-op members distribute election gazettes or legislative reports when they deliver Co-op information leaflets. In the early days, Netto candidates also attended the Co-op's formal and informal meetings during the campaigns to solicit support. Active Co-op members are potential candidates and a source of volunteers for election campaigns. In contrast, even at its peak, members of Tokyo's Netto never exceeded 2,000, and they have declined significantly since then. On the other hand, the Life Club Co-op boasts a much larger membership, which constitutes a stable support base for the Netto candidates, with 33 local Co-ops in 21 prefectures boasting 400,000 members.Footnote 13

However, laws regulating the political activities of co-ops were reinforced in 2005 to require all co-ops to maintain political neutrality. That change shrank the Life Club Co-op members’ political activities. Recently joined members of the Life Club Co-op are not aware of the history of Netto. Most of them are not as interested in political engagement, like the members of the 1990s.Footnote 14 Over time, the Life Club Co-op itself became just one of the many coops existing in Japan. Many Nettos continue to rely on the aging founding members to run the party and carry out political campaigns, and the size of Netto’s core membership is decreasing, too. This weakening of Netto’s traditionally stable support base constitutes a fundamental challenge.

Constituency and Platform

The most conspicuous keyword that represents the Netto party is Seikatsusha, meaning roughly “life makers” or “ordinary people going about their lives.” Although the meaning of Seikatsusha has changed over time in Japan, its consistent emphasis is on locality, integration of domestic and public spheres, and participation in both production and consumption (Amano Reference Amano and Stickland2011). Here “local” has a particular significance for Seikatsusha, for it is in a specific locale that life issues take place. Seikatsusha emphasizes autonomy and self-governance, but it differs from the Western concept of citizen, which is strongly associated with the public sphere and norms of universality.

Netto adopted the gender-neutral concept of Seikatsusha for the party's idealized constituency. However, due to a strict gender division of labor in Japan, seikatsusha are virtually all full-time housewives. To be more precise, only housewives operating outside the full-time paid labor market can avail themselves of the spare time and free spirit for the cooperative activities that promote alternative living in cities (Iwane Reference Iwane1993). A survey of the Tokyo Netto members in the early 1990s found that most Netto members were unemployed housewives. More than 60% were from high-income households, with their husband's annual salary surpassing eight million yen (~80,000 USD) (Watanabe Reference Watanabe, Sato, Amano and Nasu1995).Footnote 15 They were active housewives who came to voice social concerns that had been neglected by conventional politics, yet whose identities and policy concerns derived from their gendered and classed positions in society.

The practical policy orientation of gendered Seikatsusha is clearly expressed in the party platform. Netto members identified garbage problems, environment, food safety, and children's welfare issues as the primary concerns of the deputy movement, far ahead of human rights and gender equality (Watanabe Reference Watanabe, Sato, Amano and Nasu1995, 203). Netto party members do not deny that they represent “women's concerns” in the legislature, but most of them do not perceive their policy concerns as women's issues, but rather as mothers’ issues. For them, women's issues seem abstract and normative, but child care and food safety are concrete policy issues, directly related to their everyday lives. As mothers of young children, they feel much more comfortable speaking about those issues since they are confident in their expertise and social status as mothers.Footnote 16

This gendered Seikatsusha identity is why Netto has been so successful as a women's local party. As LeBlanc (Reference LeBlanc1999) describes, housewives’ caretaking roles at home and in the neighborhood form a pivotal ground for their claims to be able to represent ordinary people's concerns as “community caretakers.” The Netto deputies brought particular women's concerns to politics, and gradually these issues gained legitimacy and became worthy of policy attention.

These platforms seemed to have contributed to recruiting young mothers of a new generation to the Netto party after the earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear accident that befell Fukushima on March 11, 2011. The triple disaster sensitized mothers with young children and transformed them into civic activists (Hasunuma Reference Hasunuma and Steele2019). It also motivated them to participate in politics. All three Netto deputies interviewed for this article who were elected after 2011 said that the nuclear accident called them to action to protect children's safety and welfare.

Although I agree with the critique that this form of participation is based on motherhood and that it imposes a potential limit on women's activism (Eto Reference Eto2005; Gelb and Estevez-Abe Reference Gelb and Estevez-Abe1998), it is also true that the Netto as a proactive women's party provides a direct channel for those mothers’ voices to be heard in politics. That is why the Netto party is still appealing to young mothers. Through these activities, women with practical interests in food safety and child-rearing transform themselves from family-oriented housewives to fellow-oriented life makers and to community-oriented citizens (Ogai Reference Ogai2005, 146–150).

Alternative Representation System

Would women run a party differently? The Netto party provides significant insights into this question. Because the Netto deputy movement started as a critique of the conventional representation system and the failure of interest-driven politics to respond to women's concerns, one important goal of the Netto was to propose an alternative representation system and to develop a party organization to realize that goal. The Netto members perceived Japanese politics as dominated by professional politicians who serviced economic interest groups and marginalized citizens’ voices (Lam Reference Lam1999; LeBlanc Reference LeBlanc1999). They contend that the distance between citizens and their representatives diverged so greatly in the conventional representation system that politics was no longer capable of taking ordinary citizens’ life issues into account or providing meaningful accountability to ordinary citizens.

Netto claims to correct this problem by treating politics as a tool with which citizens can protect their lives and flourish. To reclaim politics as a space that fosters citizens’ political expression, Netto developed a concept of direct representation, which enables the will of the constituency to direct and circumscribe representatives’ behavior. This preference for a delegate model of representation, as opposed to a trustee or Burkean model, inspired Netto to name its representatives Dairinin (deputies or delegates) rather than the more conventional term Giin (legislators, members of an assembly). Not only are Dairinin direct advocates for their constituencies, but the activities of Dairinin at local councils are meant to be part of a larger Seikatsusha movement for a change of life in local communities.

To fulfill this alternative representation norm in praxis, the Netto employed three unique organizational structures: (1) rotation and term limit of deputies, (2) donation of deputies’ salaries to the organization, and (3) volunteerism in campaigns.Footnote 17 Rotation in office enforced by mandatory term limits is a unique characteristic of Netto, adopted to “avoid overprivilege” of deputies (Tokyo Seikatsusha Network HP). According to these rules, all deputies are expected to quit elected office after serving two to three terms (eight or 12 years) in local councils. The idea is that the former deputies return to their communities to utilize their experiences to assist other citizens. The party replaces them with new candidates in the next election. In that way, the party can be self-sufficient and independent in terms of both resources and finance as well as retain close relations between citizens and deputies.

However, some deputies wish to run even after completing the fixed terms. They believe they can play more influential roles in the policy-making process after they become experienced legislators. In principle, all regional Nettos keep the original rules, but new rules have been added in response to the wishes of Dairinin. For example, the Tokyo Netto adopted a stage system that would allow a deputy to serve a total of six terms if she decides to run for the prefectural election after three terms in the local council. But in reality, changing the stage from local to prefectural office is not easy. Prefectural election requires far more resources, and even if the Netto candidates win seats, they are only a tiny portion of a larger legislature.

Donation of deputies’ remuneration is another defining character of the interdependent relationship between Netto and deputies. Deputies are obliged to donate a significant portion, if not all, of their remuneration to Netto. Each prefectural Netto headquarters collects all Netto deputies’ salary within the prefecture, then distributes to each deputy 200,000 yen (~2,000 USD). The rest is deposited in the headquarters, then redistributed to each regional party unit. These donations are an important part of the revenue to fund everyday activities of the Netto party. The party in turn takes full responsibility for the deputies’ campaign financing and staff. The logic behind this is that the Netto party, not a candidate, remains accountable to its constituency by disclosing the flow of money. It would also facilitate campaigns for office by ordinary citizens with poor resources.

However, there have been discussions on this rule as well. Unless a potential deputy has extra revenue such as a husband's income, she will hesitate to run on Netto’s platform due to the expectation of low income. Some Netto organizations provide child allowances to deputies with children, but nevertheless obligatory donation of salaries it is a significant obstacle for many potential women and men candidates, particularly those who are the main earners of their families.

Finally, Netto values volunteerism and participation. Voluntary participation in activities beyond self-interest is seen as necessary because it can transform citizens from passive recipients of services to proactive agents for change. Amano summarizes these characteristics of the Netto deputy movement as “a practical application of participatory politics by women who hitherto had been said to ‘go no further than voting’ ” (2011, 147). Many volunteers who see themselves as ordinary mothers or residents gain political knowledge and experience through volunteering in campaigns. Many of them later become candidates.

From the candidates’ point of view, voluntarism lowers the hurdles for women candidates who aspire to run for office. Because Netto employs a rotation system for its deputies, many candidates are new to the party. Veteran volunteers who have participated in previous election campaigns work as experienced election managers and help candidates conduct campaigns in their districts. However, the challenge in recent days is to recruit both new candidates and party members. Like most other women's movement organizations in Japan, Netto is also having a hard time in reaching out and recruiting constituents of younger generations.Footnote 18

This emphasis on ordinary people's voluntary “amateur politics” also creates dilemmas. Netto faces a difficult challenge to “avoid creating ‘professional’ politicians without sacrificing its most experienced activists, and balance the advantages of its ‘regular housewife’ volunteer image with the need for devoted activists with the freedom and desire to make movement objectives a priority” (LeBlanc Reference LeBlanc1999, 161). Moreover, Netto’s policy appeal to its main constituency has gradually eroded, partly because women's economic independence is getting valued more than women's role as life maker and partly because other new parties have added life issues to their platforms, making it difficult for Netto to differentiate itself from other major and local parties.

Many regional Nettos have been pressed to reconsider this representation system. They are also conscious of critiques that suggest that their agenda and praxis limit the potential to move beyond the boundary of an overwhelmingly “housewife party.” Although most regional Nettos still retain the original representation rules, including rotation and term limits, the party has been debating how to reach out to citizens beyond the confines of its traditional constituency. Some Nettos have recruited male candidates to expand their appeal and break with their image as a housewife party.Footnote 19 However, such efforts risk diluting the party's identity and losing support from its traditional constituency. Whether or not Netto can successfully expand to a larger women citizens’ party still seems to be an open question.

CONCLUSION

In this article, I have examined the Japanese local party Netto as an example of a distinctive type of women's party. Netto is the longest-lived and most successful party in the global history of women's parties (see Cowell-Meyers, Evans and Shin, this issue). To capture how Netto is different not only from conventional political parties but also from parties organized to promote feminist platforms, I have drawn on two criteria of women's descriptive and substantive representation within parties. I define the Netto party as a proactive women's party in which women dominate party membership, candidacy, and leadership, and which promotes practical women's interest in politics. The gendered characteristics of Netto have facilitated the electoral success of the party in urban areas and made the party appealing to middle-class housewives and mothers, including young mothers who came to be politicized by the threat to their children's health posed by nuclear radiation after the 2011 Fukushima nuclear accident.

At the same time, Netto’s inability to reach out to a broader constituency beyond urban housewives and young mothers has begun to constrain its growth and recent electoral performance. The peak of the Tokyo Netto was 2005, when it obtained 4.1% of total votes for the metropolitan assembly. In the same year, the government issued an administrative guidance requiring the co-ops to comply with the political neutrality clause of the co-op law. Since then, Netto has virtually stopped growing, and struggles to maintain its previous achievements.Footnote 20 In the 2015 election, the Tokyo Netto still sent its deputies to 31 local assemblies among 62 legislative bodies at various levels in metropolitan Tokyo. However, a losing trend continued in the April 2019 election.

To cope with the challenges, some Netto have attempted to expand their support by fielding single women or men candidates. Other Nettos are trying to incorporate a broader range of women's issues. But the biggest deputy candidate pool still seems to be mothers who are active in children's safety issues. This implies that Netto will continue to represent mothers’ concerns over women's rights or labor issues with greater appeal to working mothers or single women.

On the other hand, as mothers’ concerns have begun to draw more political attention, other parties and independent candidates also have incorporated those issues in their platforms. This suggests that some women now have greater voice in politics, whereas other women's concerns remain underrepresented. Of course, Netto does not have to represent all women, and it cannot, because women are not a monolithic group.

However, Netto’s position as a niche women's party has important implications for women's descriptive and substantive representation in Japanese local politics. Netto is often the only party that explicitly speaks for “women” in local legislatures (Yoon and Osawa, Reference Yoon and Osawa2017). Even though local politics is seen as closer to citizens’ life, it has been no less dominated by men. Women have lacked the formal institutional mechanisms to be included in mainstream political parties. Some women, like the members of Netto, responded to this by forming their own local parties, which provide an important institutional channel for the participation of “ordinary” housewives and mothers in politics. This has the potential to blur the boundary between private and public, which is entrenched in the gendered division of life, leading to a transformation of male-dominated electoral politics. Netto proves that not all women's parties compete on a feminist platform, but they are still playing an important role in changing male-dominated electoral politics. In this aspect, women's activism based on traditional women's roles may not always be opposed to feminist goals in the long run.