Valence matters in voting behavior, but how, exactly? A large body of scholarly research concludes that valence adds a second important dimension to the standard policy-based electoral competition. Valence issues have the peculiar property that voters have identical preferences about them. They all prefer more to less of a given valence attribute. For example, they prefer more to less competent politicians, and they prefer more to less honest politicians. Fittingly, Groseclose (Reference Groseclose2007) argues that valence adds “half” a dimension to the standard one-dimensional Downsian model of electoral competition.

Indeed, most formal models of electoral competition add a single and separable valence component to the voters’ utility function (for example, Londregan and Romer Reference Londregan and Romer1993; Ansolabehere and Snyder Jr. Reference Ansolabehere and Snyder2000; Groseclose Reference Groseclose2001; Aragones and Palfrey Reference Aragones and Palfrey2002, Reference Aragones and Palfrey2004; Schofield Reference Schofield2003, Reference Schofield2007; Adams and Merrill Reference Adams and Merrill2009; Castanheira, Crutzen and Sahuguet Reference Castanheira, Crutzen and Sahuguet2010). The utility U i of voter i is therefore represented as:

It is a positive function of the valence δ

c

of candidate C and a negative function of the difference

between x

i

and x

c

, the voter’s and the candidate’s positions along a policy dimension, where

δ

c

,x

i

and

![]() $x_{c} \in {\Bbb R}$

(Groseclose Reference Groseclose2001).

Voters hold homogeneous views with regard to the valence issue, and policy and

valence dimensions have the same saliency. Variants to this standard approach

include uncertainty over the valence advantage (Londregan and Romer Reference Londregan and Romer1993; Adams and Merrill Reference Adams and Merrill2009), multiple policy dimensions and valence

traits (Ansolabehere and Snyder Reference Ansolabehere and Snyder2000;

Adams et al. Reference Adams, Merrill, Simas and Stone2011), and

different types of politicians (Groseclose Reference Groseclose2001; Adams and Merrill Reference Adams and Merrill2009).

$x_{c} \in {\Bbb R}$

(Groseclose Reference Groseclose2001).

Voters hold homogeneous views with regard to the valence issue, and policy and

valence dimensions have the same saliency. Variants to this standard approach

include uncertainty over the valence advantage (Londregan and Romer Reference Londregan and Romer1993; Adams and Merrill Reference Adams and Merrill2009), multiple policy dimensions and valence

traits (Ansolabehere and Snyder Reference Ansolabehere and Snyder2000;

Adams et al. Reference Adams, Merrill, Simas and Stone2011), and

different types of politicians (Groseclose Reference Groseclose2001; Adams and Merrill Reference Adams and Merrill2009).

Only Groseclose (Reference Groseclose2001, Appendix B) takes seriously the possibility that policy and valence components are non-separable. Valence may take what he calls the competency form. He argues:

Suppose valence represents the candidate’s competency for implementing the policy position that he or she announces. Here, it is reasonable to believe that the voter appreciates a candidate’s competency more when the candidate has adopted a policy that he or she likes… That is, the marginal gains from valence is [sic] larger when policy distance is smaller (882).

These models are designed to produce expectations about politicians’ positioning on the policy-valence space. Valence also plays a central role in the literature that conceives elections as screening mechanisms (for example, Besley and Coate Reference Besley and Coate1997; Fearon Reference Fearon1999; Caselli and Morelli Reference Caselli and Morelli2004; Messner and Polborn Reference Messner and Polborn2004; Mattozzi and Merlo Reference Mattozzi and Merlo2008; Galasso and Nannicini Reference Galasso and Nannicini2011). Galasso and Nannicini (Reference Galasso and Nannicini2011), for instance, assume that in a one-dimensional policy space, only centrist voters care about valence, while extreme voters choose their preferred party, regardless of its valence. This is equivalent to assuming that voters do not hold homogeneous views about valence, or that only a subset of voters assigns a saliency weight to valence that is strictly greater than zero. More extremely, Caselli and Morelli (Reference Caselli and Morelli2004) propose a model of citizen-candidates in which valence is the only relevant dimension of competition. These works are primarily concerned with the selection mechanisms of specific types of low- or high-valence politicians.

Regardless of whether the focus is on competition or selection, these models rely on a set of assumptions about voting behavior. But how exactly do voters behave in a multi-dimensional choice setting? How do they choose between candidates who embody more and less likable traits? Empirical studies of voting behavior provide contradicting results. For instance, Green and Hobolt (Reference Green and Hobolt2008) for Britain and Buttice and Stone (Reference Buttice and Stone2012) for the United States find that valence voting plays a greater role as parties and candidates converge ideologically. Cross-country studies suggest otherwise. Pardos-Prado (Reference Pardos-Prado2012) shows that the effect of valence on the propensity to vote for a party increases as ideological polarization intensifies; similarly, Clark and Leiter (Reference Clark and Leiter2014) find that the valence effects on electoral performance increase as parties diverge from the mean voter’s ideological position.Footnote 1

In this article, we employ an experimental technique called conjoint analysis to understand how voters make decisions when faced with multi-dimensional choices. We have designed a so-called stated preference experiment in which participants are asked to choose between candidates who vary along three valence (education, income and honesty) and two ideological (attitudes toward taxation and spending and the rights of same-sex couples) attributes. We administered the experiment to 347 subjects in 2012–13, resulting in 9,352 votes over pairwise compared candidates. Our results indicate that education and integrity, but not income, indeed behave like valence issues in which voters prefer more to less. More interestingly, policy positions and valence attributes are non-separable. They interact, apparently taking the competency form. The impact of higher valence on the likelihood of voting for a candidate is conditional on the candidate’s policy positions: it is higher when the candidate’s positions are closer to those of the respondents. Finally, when push comes to shove, policy trumps valence. Voters are ready to trade a higher-valence candidate, with whom they do not share policy views, for a lower-valence one with whom they share such views.

In the next section, we formalize voters’ choices in a multi-dimensional space employing spatial voting theory, emphasizing the importance of separable and non-separable preferences and of the saliency of the dimensions. We then introduce the design of the experiment, explain the estimation model and discuss the main results.

Voter choice between candidates with multiple attributes

Let C={1, …, C} be a set of candidates,

A={1, …, A} a set of attributes, and

![]() ${\bf v}_{{\bf a}} =(v_{a}^{1} ,\,\,\ldots,v_{a}^{l} )$

an l-tuple of values of attribute

a, where

${\bf v}_{{\bf a}} =(v_{a}^{1} ,\,\,\ldots,v_{a}^{l} )$

an l-tuple of values of attribute

a, where

![]() $v_{a}^{l} $

is the lth value of attribute

a and l≥2 for

$v_{a}^{l} $

is the lth value of attribute

a and l≥2 for

![]() $\forall a$

. V is the set of all attributes’ values, and the

profile of the cth candidate is denoted by a column vector of

attributes’ values

$\forall a$

. V is the set of all attributes’ values, and the

profile of the cth candidate is denoted by a column vector of

attributes’ values

![]() ${\bf P}_{{\bf c}} =[v_{{{\rm 1}c}} \,\,\ldots\,\,v_{{ac}} ]'$

, where v

ac

is the value of attribute a for candidate

c. For example, there may be three relevant attributes—such

as education, integrity and position on taxation and spending—each of which can

take any of three ordered values. The profile of a candidate can be

characterized by low education, high integrity and a pro-spending position.

${\bf P}_{{\bf c}} =[v_{{{\rm 1}c}} \,\,\ldots\,\,v_{{ac}} ]'$

, where v

ac

is the value of attribute a for candidate

c. For example, there may be three relevant attributes—such

as education, integrity and position on taxation and spending—each of which can

take any of three ordered values. The profile of a candidate can be

characterized by low education, high integrity and a pro-spending position.

The ideal candidate of respondent i is represented by the

column vector Θ

i

![]() $=[{\rm \theta }_{{i{\rm 1}}} ,\,\,\ldots\,\,,{\rm \theta }_{{ia}} ]'$

, where θ

ia

is her ideal value of attribute a and

$=[{\rm \theta }_{{i{\rm 1}}} ,\,\,\ldots\,\,,{\rm \theta }_{{ia}} ]'$

, where θ

ia

is her ideal value of attribute a and

![]() $\theta _{{ia}} \in {\bf V}$

. In a pairwise comparison of candidates’ profiles (that is,

c = 2), let

$\theta _{{ia}} \in {\bf V}$

. In a pairwise comparison of candidates’ profiles (that is,

c = 2), let

![]() $Y_{i} ({\bf P}_{{\bf c}} )\in \{ {\rm 0},{\rm 1}\} $

be the potential binary outcome of respondent

i over a candidate with profile P

c

. A value of 1 indicates that the respondent would choose the

cth profile if she got the treatment P

c

, while a value of 0 means that she would not choose such a profile.

Since respondents must choose one profile in each decision,

$Y_{i} ({\bf P}_{{\bf c}} )\in \{ {\rm 0},{\rm 1}\} $

be the potential binary outcome of respondent

i over a candidate with profile P

c

. A value of 1 indicates that the respondent would choose the

cth profile if she got the treatment P

c

, while a value of 0 means that she would not choose such a profile.

Since respondents must choose one profile in each decision,

![]() $\mathop{\sum}\nolimits_{c={\rm 1}}^C {Y_{i} ({\bf P}_{{\bf c}} )={\rm 1}} $

for

$\mathop{\sum}\nolimits_{c={\rm 1}}^C {Y_{i} ({\bf P}_{{\bf c}} )={\rm 1}} $

for

![]() $\forall i$

. Employing the weighted Euclidean distance of spatial voting

theory (Enelow and Hinich Reference Enelow and Hinich1984; Hinich

and Munger Reference Hinich and Munger1997, 80), we

have:

$\forall i$

. Employing the weighted Euclidean distance of spatial voting

theory (Enelow and Hinich Reference Enelow and Hinich1984; Hinich

and Munger Reference Hinich and Munger1997, 80), we

have:

where S i is a symmetric positive-definite matrix of order A.Footnote 2 The diagonal elements in S i measure the salience that respondent i attaches to each attribute, and the off-diagonal elements capture the interaction across attributes. If S i is an identity matrix, respondent i attaches the same weight to each attribute, and preferences are separable across attributes. If the diagonal elements in S i take different values, the respondent assigns more salience to some attributes in her voting decision. For instance, she may consider a candidate’s integrity to be more important than his income. In a bidimensional space, indifference contours take an elliptical rather than a circular shape. If the off-diagonal elements in S i are different from zero, preferences are non-separable and attributes interact along the lines of the competency form discussed by Groseclose (Reference Groseclose2001). Attributes can be positive (negative) complements if a higher level of one attribute makes a respondent want more (less) of another attribute.Footnote 3 For instance, a voter may value a candidate’s level of education more when the candidate shares the voter’s opinions on policy. If a candidate’s reputation is tainted, she may display more conservative attitudes toward taxation and spending.

A conjoint analysis voting experiment

Conjoint analysis is a method that allows us to isolate the aspects that influence a respondent’s choice in a multi-dimensional space. It originates from mathematical psychology (Luce and Tukey Reference Luce and Tukey1964) and has been extensively employed in marketing research and economics to measure consumer preference, forecast demand and develop new products (Green and Rao Reference Green and Rao1971; Green, Krieger and Wind Reference Green, Krieger and Wind2001; Hensher, Rose and Greene Reference Hensher, Rose and Greene2005; Raghavarao, Wiley and Chitturi Reference Raghavarao, Wiley and Chitturi2010). It has been applied only very recently to research questions in political science (Hainmueller and Hopkins Reference Hainmueller and Hopkins2012; Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto Reference Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto2014).

We have designed a conjoint analysis voting experiment to assess how

candidates’ attributes related to valence and ideology affect voters’ choices.

Respondents are subject to K choice tasks in which they have

to choose between two generically labeled candidates A and B.Footnote

4

These candidates are characterized by five attributes, each of which

takes one of three values; hence C={1,2}, A={1, …, 5}

and

![]() ${\bf v}_{{\bf a}} =(v_{a}^{1} ,v_{a}^{2} ,v_{a}^{3} )$

where a=1, … 5.

${\bf v}_{{\bf a}} =(v_{a}^{1} ,v_{a}^{2} ,v_{a}^{3} )$

where a=1, … 5.

The five attributes and their values are described in Table 1; three are meant to be related to valence, and two to ideology or policy. Following Stokes (Reference Stokes1963) seminal contribution, the literature offers a long list of possible valence factors, from the strength of the economy (for example, Butler and Stokes Reference Butler and Stokes1969; Fiorina Reference Fiorina1975; Anderson Reference Anderson2000; Palmer and Whitten Reference Palmer and Whitten2000; Lewis-Beck, Nadeau and Elias Reference Lewis-Beck, Nadeau and Elias2008) to issue ownership (for example, Budge and Farlie Reference Budge and Farlie1983; Clarke et al. Reference Clarke, Sanders, Stewart and Whiteley2004; Bélanger and Meguid Reference Bélanger and Meguid2008; Green and Hobolt Reference Green and Hobolt2008), party unity (Clark Reference Clark2009), incumbency, name recognition and campaigning skills (for example, Fiorina Reference Fiorina1981; Enelow and Hinich Reference Enelow and Hinich1982; Londregan and Romer Reference Londregan and Romer1993; Groseclose Reference Groseclose2001; Stone and Simas Reference Stone and Simas2010; Adams et al. Reference Adams, Merrill, Simas and Stone2011). These factors are not particularly meaningful or useful in pairwise comparisons between generically labeled candidates. They are either context specific or instrumental—and the latter are not valued intrinsically by voters. In light of the models reviewed above, we are interested in candidate-specific and character-based attributes related to competence and integrity (for example, McCurley and Mondak Reference McCurley and Mondak1995; Funk Reference Funk1996; Kulisheck and Mondak Reference Kulisheck and Mondak1996; Funk Reference Funk1999; Mondak and Huckfeldt Reference Mondak and Huckfeldt2006; Clark Reference Clark2009; Stone and Simas Reference Stone and Simas2010; Adams et al. Reference Adams, Merrill, Simas and Stone2011; Clark and Leiter Reference Clark and Leiter2014).

Table 1 Attributes and Attribute Levels

Directly attributing a level of competence to a candidate would make the whole exercise pleonastic. The choice between a competent candidate and an incompetent one is banal. We instead employ education and income, which are considered proxies for competence in several recent models (Caselli and Morelli Reference Caselli and Morelli2004; Messner and Polborn Reference Messner and Polborn2004; Galasso and Nannicini Reference Galasso and Nannicini2011). Higher educational attainment is plausibly related to greater perceived competence, as it indicates (or even determines) higher cognitive and problem-solving skills in policy making. The link between income and competence, or valence more generally, may raise a few eyebrows. Yet citizen-candidate models, which seek to fully endogenize candidacies by removing the distinction between the electorate and the political class, and are particularly concerned with politicians’ qualities (Dewan and Shepsle Reference Dewan and Shepsle2011), unabashedly assign to income a strong connotation of valence as “a measure of market success and ability” (Galasso and Nannicini Reference Galasso and Nannicini2011, 79). For Caselli and Morelli (Reference Caselli and Morelli2004, 775), “voters use [candidates’] market incomes as a signal of their competence” in office. Yet income may signal other features, such as class membership, and therefore display no valence behavior. Our experiment will test these assertions.

The education attribute includes three levels of attainment: junior high school diploma, high school diploma and university degree. In Italy, they are called licenza media, diploma superiore and laurea. The levels of income are low, medium and high. Low income is specified as below €900 a month, which is approximately the second decile of the 2009 income distribution in Italy. High income is specified as above €3,000 a month, approximately the 95th percentile.Footnote 5

The honesty attribute is introduced as additional information, thus avoiding more laden terms such as integrity. Corruption is the most common office-related crime a politician is likely to be charged with. Thus a candidate may have been convicted of corruption, be under investigation for corruption or have a clean sheet.

Candidates also differentiate along policy positions that are derived from well-established cleavages: the liberal-interventionist economic divide and the liberal-conservative social one (for example, Kitschelt Reference Kitschelt1994; Benoit and Laver Reference Benoit and Laver2006, 160). To capture the former, we established that candidates may want to increase the provision of social services, even at the cost of more taxation, to maintain the current levels, or to cut taxes, even at the cost of fewer social services. These are frequently the top priorities of government according to Italian public opinion (European Commission 2010, 24). For the liberal-conservative social dimension, candidates may want to grant no family-related rights to same-sex couples, to grant these couples some rights or even the same rights as traditional families. This is currently the most-debated issue that captures the liberal-conservative social divide in Italy. Others, such as abortion and euthanasia, are less prominent.

Table 2 illustrates an example of a choice task. Note that it does not offer the possibility of abstention. Although including this option would better reflect the true situation in which voters find themselves, we are not interested in participation in this context. Our objective is to assess the impact of candidates’ attributes on voters’ choice. A no-vote alternative is a hindrance for our analysis, because the only information that can be derived from abstention is that the respondent would prefer not to choose. We do not obtain any information about why this is so. As Hensher, Rose and Greene (Reference Hensher, Rose and Greene2005, 176) argue, “by forcing decision makers to make a choice, we oblige decision makers to trade off the attribute levels of the available alternatives and thus obtain information on the relationships that exist between the varying attribute levels and choice.”

Table 2 Example of a Choice Task

Experimental Design Considerations

Which candidate profiles should be included in the conjoint analysis, and

how should they be paired? A full factorial design enumerates all possible

treatment combinations (that is, profiles) (Hensher, Rose and Greene Reference Hensher, Rose and Greene2005, 109). With five attributes and

three levels per attribute, we have 243 (that is, 35) different

profiles. Since we ask respondents to pairwise compare candidates, the full

enumeration of choice tasks amounts to 29,403, that is

![]() $\left( {\matrix{ {{\rm 243}} \cr {\rm 2} \cr } } \right)$

, combinations. Such a design is clearly unfeasible. We

will therefore use only a fraction of these combinations—a so-called

fractional factorial design.

$\left( {\matrix{ {{\rm 243}} \cr {\rm 2} \cr } } \right)$

, combinations. Such a design is clearly unfeasible. We

will therefore use only a fraction of these combinations—a so-called

fractional factorial design.

The minimum number of profiles of a fractional factorial design is determined by the degrees of freedom we need for the subsequent model estimation. Since the alternative candidates are unlabeled, estimating the main effects of five attributes requires at least six degrees of freedom for a linear model and, because each attribute takes three values, at least 11 degrees for a non-linear model. Moreover, testing the competency form entails interactions. Adding an interaction between two attributes requires the estimation of one more parameter (for a linear model) and four more parameters (for a non-linear model). In other words, if we want to estimate the main effects and, say, two interactions, we need at least eight degrees of freedom for a linear model and 19 degrees for a non-linear model.

Additionally, a statistically efficient fractional factorial design must be orthogonal, in which columns display zero correlation (Hensher, Rose and Greene Reference Hensher, Rose and Greene2005, 115). In other words, the levels that an attribute takes across all choice tasks should be statistically independent from the levels other attributes take. Orthogonality may require a number of combinations that exceeds the minimum requirement imposed by the degrees of freedom (in our case, 19 for a non-linear model). However, for unlabeled designs, only within-alternative orthogonality needs to be maintained (Hensher, Rose and Greene Reference Hensher, Rose and Greene2005, 152). Thus the education attribute of candidate A across all the choice tasks does not need to be orthogonal to the education attribute of candidate B. Finally, the design should be balanced. Each level of any given attribute should appear the same number of times.

Since we require only within-alternative orthogonality, we generated a main-effects orthogonal design for five attributes with three levels for each attribute, setting the minimum number of cases (rows) at 27. The design is balanced, because each level of each attribute appears nine times. We have assigned attributes to the columns of the design in order to ensure statistically efficient estimations of the main effects and of the interactions between education and the two policy dimensions (for details on the procedure, see Hensher, Rose and Greene Reference Hensher, Rose and Greene2005, 127–50). Seven of the possible 10 two-way interactions between attributes display zero correlation with the main effects. Several interactive terms are also uncorrelated with each other. In practice, this means that we can efficiently estimate the marginal effects of all 10 pairwise interactions among the five attributes.Footnote 6 We have now 27 orthogonal profiles of candidate A. We have then randomized the sequence of these profiles and assigned them to candidate B, making sure that the randomized combination does not match the original. This procedure ensures within-alternative orthogonality (Hensher, Rose and Greene Reference Hensher, Rose and Greene2005, 152).

The core of the experiment consists of 27 choice tasks (that is, K = 27) in which respondents are requested to choose between two candidates’ profiles. The order of the attributes, as it appears in Table 2, does not change for each respondent in order to ease the cognitive burden, but the sequence of tasks is randomized across respondents in order to minimize primacy and recency effects.

The only applications of conjoint analysis in political science are in the field of public opinion (Hainmueller and Hopkins Reference Hainmueller and Hopkins2012; Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto Reference Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto2014). In light of the formal literature reviewed above, our interest is more circumscribed. We want to analyze how respondents reconcile candidates’ valence and policy features in their voting choices. We are less interested in how different types of respondents prefer different candidates, although trade-offs may differ across types. Given the nature of our inquiry, a set of relatively homogeneous respondents allows us to better control for unobservables that may confound the interaction between attributes (Hensher, Rose and Greene Reference Hensher, Rose and Greene2005). We have therefore involved 155 undergraduate students in the period between February and May 2012, and then repeated the exercise with a further 192 students between January and May 2013. The experiment, structured as an online survey, has been administered by the Opinion Polls Laboratory (Laboratorio Indagini Demoscopiche) of the Università degli Studi di Milano. Clearly, our results are not generalizable to a wider population, but we are nevertheless able to highlight similarities with recent public opinion studies (Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto Reference Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto2014). Future research should consider developing a representative online sample for further corroborating these findings.

Estimation

To estimate how candidates’ attributes influence respondents’ choices, we

employ a binomial model with a conditional logit link function. Voting is

assumed to be generated by a Bernoulli process. The stochastic component of the

model is therefore

![]() $Y_{{ic}} \sim Bernoulli(y_{{ic}} \!\mid\!\pi _{{ic}} ),$

where

$Y_{{ic}} \sim Bernoulli(y_{{ic}} \!\mid\!\pi _{{ic}} ),$

where

![]() $\pi _{{ic}} =Pr(Y_{{ic}} =1\!\mid\!{{\tf="OT8244d044_BI"β} )}$

for respondent i and candidate

c. The systematic component is

$\pi _{{ic}} =Pr(Y_{{ic}} =1\!\mid\!{{\tf="OT8244d044_BI"β} )}$

for respondent i and candidate

c. The systematic component is

$$\pi _{{ic}} ={{\exp \left[ {\left( {\mathop{\sum}\nolimits_{{\rm a=1}}^{\rm 4} {{\it β} _{a} } v_{{ac}} } \right){\,+\,}{\it β} _{{\rm 5}} v_{{{\rm 1}c}} v_{{{\rm 4}c}} {\,+\,}{\it β} _{{\rm 6}} v_{{1c}} v_{{{\rm 5}c}} {\,+\,}({\tf="OT8244d044_BI"β} \circ \bi R_{i} ) \cdot P_{c} } \right]} \over {\mathop{\sum}\nolimits_{c={\rm 1}}^{\rm 2} {\exp } \left[ {\left( {\mathop{\sum}\nolimits_{{\rm a=1}}^{\rm 4} {{\it β} _{a} } v_{{ac}} } \right){\,+\,}{\it β} _{{\rm 5}} v_{{{\rm 1}c}} v_{{{\rm 4}c}} {\,+\,}{\it β} _{{\rm 6}} v_{{1c}} v_{{{\rm 5}c}} {\,+\,}({\tf="OT8244d044_BI"β} \circ \bi R_{i} ) \cdot P_{c} } \right]}}$$

$$\pi _{{ic}} ={{\exp \left[ {\left( {\mathop{\sum}\nolimits_{{\rm a=1}}^{\rm 4} {{\it β} _{a} } v_{{ac}} } \right){\,+\,}{\it β} _{{\rm 5}} v_{{{\rm 1}c}} v_{{{\rm 4}c}} {\,+\,}{\it β} _{{\rm 6}} v_{{1c}} v_{{{\rm 5}c}} {\,+\,}({\tf="OT8244d044_BI"β} \circ \bi R_{i} ) \cdot P_{c} } \right]} \over {\mathop{\sum}\nolimits_{c={\rm 1}}^{\rm 2} {\exp } \left[ {\left( {\mathop{\sum}\nolimits_{{\rm a=1}}^{\rm 4} {{\it β} _{a} } v_{{ac}} } \right){\,+\,}{\it β} _{{\rm 5}} v_{{{\rm 1}c}} v_{{{\rm 4}c}} {\,+\,}{\it β} _{{\rm 6}} v_{{1c}} v_{{{\rm 5}c}} {\,+\,}({\tf="OT8244d044_BI"β} \circ \bi R_{i} ) \cdot P_{c} } \right]}}$$

where v ac is the value of attribute a for candidate c, with the interactions between education (v 1c ) and the two policy dimensions (v 4c, v 5c). β o R i is the Hadamard product of row vectors of betas and socio-demographic and political characteristicsFootnote 7 of respondent i, while P c is the column vector of candidates’ attributes. Respondent characteristics must interact with candidate attributes, because they do not display within-group variance—that is, they do not vary across profiles.

Valence, ideology and voting

The results of the estimation are reported in Appendix Table A1. In this section, we first assess whether the attributes we selected behave as expected. Next, we evaluate whether respondents’ preferences take the competency form. Finally, we analyze how respondents trade off profiles of candidates in their voting decisions. The online appendix includes diagnostic tests.

The Behavior of Valence and Policy Attributes in Voting Decisions

Do the first three attributes indeed behave like valence issues in which voters prefer more to less? Do the last two attributes display the features of policy issues that split voters into different groups? In other words, do the core assumptions underpinning formal models of policy valence-based electoral competition hold? Are the measures of valence used in recent formal and empirical analyses valid?

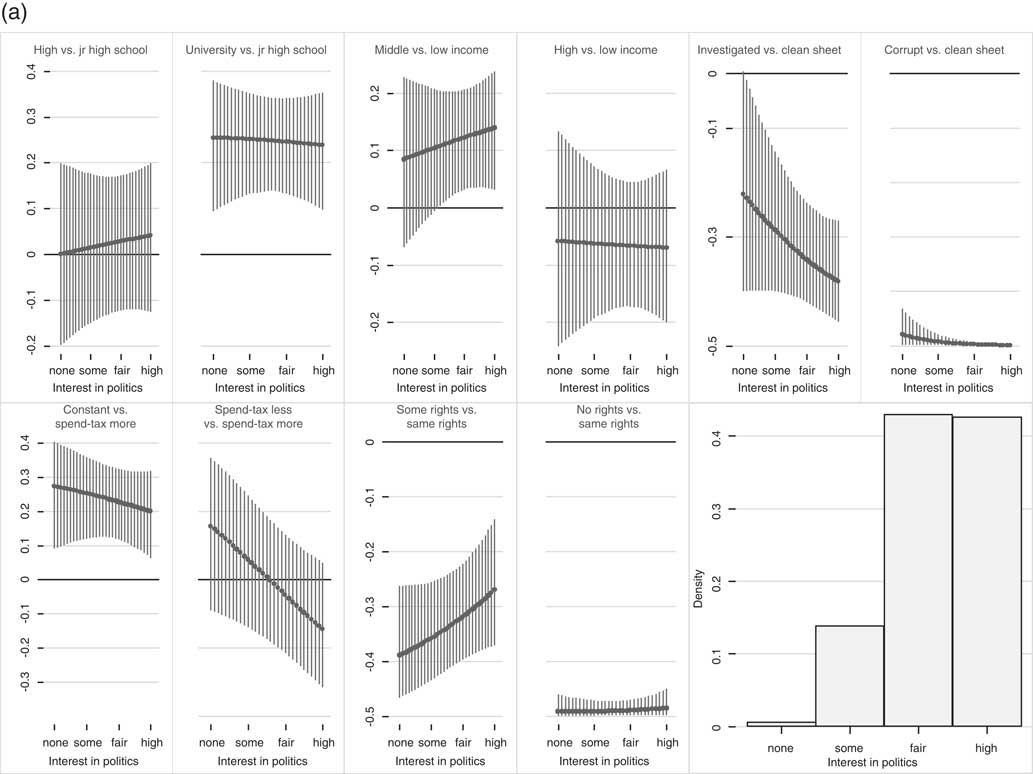

Figures 1a to 1c display the marginal effects of different attributes on the probability that respondents will vote for a particular candidate, at different levels of respondents’ interest in politics, left-right self-placement and issue saliency (see the online appendix for similar figures on the remaining traits).Footnote 8 For instance, the upper-left panel in Figure 1a displays on the vertical axis the marginal effect on the probability that respondents will vote for a candidate with a high school diploma compared to one with a junior high school diploma, at different levels of interest in politics declared by the respondents. The dots indicate the mean predicted probabilities and the lines the 95 percent confidence intervals. The bottom right panel is a histogram of respondents’ traits.

Fig. 1a Marginal effects of candidate attributes at different levels of respondents’ interest in politics Note: non-varying attributes are set at their baseline values (junior high school diploma, low income, clean, more taxation and spending, same rights to same-sex couples).

Fig. 1b Marginal effects of candidate attributes at respondents’ different left-right self-placements Note: non-varying attributes are set at their baseline values (junior high school diploma, low income, clean, more taxation and spending, same rights to same-sex couples).

Fig. 1c Marginal effects of candidate attributes at different levels of respondents’ saliency attached to attribute Note: non-varying attributes are set at their baseline values (junior high school diploma, low income, clean, more taxation and spending, same rights to same-sex couples).

To a large extent, education behaves like a valence attribute. For almost any respondent trait, a university-educated candidate is significantly more likely to be preferred over a candidate with only a junior high school diploma. For instance, assuming intermediate values for other traits,Footnote 9 respondents are between 23.8 and 25.5 percentage points more likely to choose the former profile, for any level of declared interest in politics (with 95 percent confidence intervals ranging from 9.7 to 37.9 percentage points). Right-, center- or left-leaning respondents are between 16.2 and 30.2 percentage points more likely to support such a candidate, with estimates ranging between 1.1 and 39.7 points. If education is considered an important attribute, a candidate with a university degree is between 23.2 and 33.5 percentage points more likely to win support, with the estimate ranging between 11.1 and 41.5 points. Yet, there are some nuances. Better-educated candidates are not significantly preferred over less-educated ones by respondents who are either strongly right-leaning or who attach limited importance to education. These subjects make up 22.8 percent of the respondent pool. Nevertheless, like in the candidate experiment of Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto (Reference Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto2014), the overall valence features of education are evident.

The same cannot be said for income. Middle-income candidates are slightly advantaged over low-income ones, especially if respondents are left-leaning and interested in politics.Footnote 10 But, noticeably, this is also true for subjects who attach limited relevance to this attribute. More importantly, rich candidates are not significantly preferred over poor ones, for any respondent trait. If anything, high income is a liability rather than an asset. Respondents who attribute fair or high importance to income are between 18.9 and 28.2 percentage points less likely to prefer a rich over a poor candidate. These results resonate well with those of Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto (Reference Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto2014), in which middle income matters, slightly, to win contests but high-income candidates are rated lower. Far from being an indicator of ability, or even competence in office (cf. Caselli and Morelli Reference Caselli and Morelli2004, 775; Galasso and Nannicini Reference Galasso and Nannicini2011, 79), respondents view high income quite suspiciously.Footnote 11

The last, somewhat obvious, result is that the valence behavior of the integrity attribute is beyond doubt. For any respondent trait, a clean candidate is significantly more likely to be preferred over a corrupt one. Even nuances are quite minor. Respondents who are either strongly right leaning or who display no interest in politicsFootnote 12 are indifferent between candidates who are clean and those who are under investigation, but these participants make up only 9.5 percent of the respondent pool.

Contrast this with candidates’ opinions on spending and taxation. Figure 1b illustrates that respondents are neatly split along the left-right axis. A candidate proposing to cut spending and taxation is 34.6 percentage points less likely to win support from a left-wing respondent and 40.3 percentage points more likely to win support from a right-wing respondent than a candidate proposing more spending and taxation. Consequently, moderately positioned candidates are favored over extremely positioned ones for most values of respondent traits—of course, with the exception of strongly left- or right-leaning subjects.

The issue of rights for same-sex couples behaves in a similar way, though less neatly. A candidate advocating no rights for same-sex couples is 50 percentage points less likely to win support from a left-wing respondent and 23.4 percentage points more likely to win support from a right-wing respondent than a candidate proposing the same rights as traditional families (the latter value is significant at the 90 percent confidence interval). Still, for most values of respondent traits, except ideology, candidates arguing for equal treatment are preferred to those willing to recognize only some rights. The young age of the respondents most likely explains these liberal views (for example, Bartels Reference Bartels2013). Having established the valence behavior of education and integrity, and the policy behavior of the positions on taxation and spending and on the rights of same-sex couples, we move on to analyze how participants trade off between these attributes.

Evidence of a Competency Form: Interaction among Education and Policy Attributes

Is it plausible to assume that valence is a separable component that is simply added to a standard policy-based dimension, as most formal models of electoral competition do? Or do valence and policy attributes interact, perhaps taking what Groseclose (Reference Groseclose2001) calls a competency form? In other words, do voters attach less value to valence when a candidate’s policy position differs from their own?

Figure 2 illustrates the marginal effects of different levels of educational attainment, our proxy for competence, on the probability that a typical respondentFootnote 13 will vote for a particular candidate policy profile (the online appendix includes the complementary Figures A4 and A5 on the marginal effects of policy positions). For instance, the top three panels display the marginal effects on the probability that a typical respondent will vote for a candidate with a high school diploma, compared to one with a junior high school diploma, across the nine combinations of policy profiles. In this case, higher education does not have much of an effect.

Fig. 2 Competency form: the interaction between education and policy positions Note: non-varying attributes are set at their baseline values (low income, clean).

Consider now the left panels in the second and third rows of Figure 2. Candidates who support spending and at least some rights for same-sex couples are between 20 and 23.4 percentage points more likely to be chosen if they have a university degree, rather than a high school diploma. These figures increase to 26.4 and 42.6 points, respectively, when university education is compared to a junior high school diploma. Conversely, if a candidate opposes the recognition of rights to same-sex couples, there is no level of education that is going to make him more palatable. A policy of opposing same-sex rights is strongly opposed by our typical respondent. Hence, the marginal gains from higher education vanish when policy distance increases—the key trait of Groseclose’s (Reference Groseclose2001) competency form.

As the right panel in the second row of Figure 2 illustrates, higher education can even become a liability. A university-educated candidate is 9.5 percentage points less likely to be chosen than a candidate with a high school diploma if, in addition to opposing rights for same-sex couples, he supports spending cuts as well (the estimate varies between 31 and 0.04 points). These two positions are strongly disliked by our typical respondent,Footnote 14 and higher competence is perceived as worrisome in this case.

For intermediate profiles, our typical respondent trades between candidate attributes, depending on their levels. Consider a candidate supporting full recognition of rights (left column of Figure A4). If he opposes spending, higher education does not increase his chances of being selected. If he supports cuts, and is poorly educated, he is between 30.9 and 35.4 percentage points less likely to be chosen than a pro-spending or pro-status quo candidate.

Take now a candidate supporting partial recognition. In the case of a status quo position on spending, a university education makes a candidate 10.9 percent more likely to be preferred compared to a high school diploma (center panel in Figure 2). In case of a pro-cuts position, a university education gives a 40.9 percentage point increase compared to a junior high school diploma (right panel in the third row).

In other words, the preferences of our typical respondents are finely balanced with intermediate profiles. If a candidate is for partial recognition but has only a junior high school diploma, a pro-status quo fiscal attitude makes him 35.3 percentage points more likely to be chosen than a spendthrift one (top row of Figure A4). Poor education makes our respondents wary of profligacy. But this does not necessarily extend to rights issues. If a candidate is pro-spending but poorly educated, a full-recognition stance still makes him 15.5 percentage points more likely to be chosen than a partial-recognition position (top row of Figure A5).

The trade-offs are indeed quite complicated in these intermediate profiles. The important point is the significant interactions between valence and policy attributes as envisaged by Groseclose’s (Reference Groseclose2001) competency form. This emerges more clearly on the dimension of same-sex couple rights. An F-test for the joint significance of the interaction terms rejects the null hypothesis that the effects of university education are identical across attribute levels (p-value ≈ 0.003). Moreover, the null hypothesis cannot be rejected when comparing candidates that support full and partial recognition (p-value≈0.38), while it is easily rejected when comparing candidates who support full and no recognition (p-value≈0.005). These results appear to indicate positive complementarity, in line with the findings of Green and Hobolt (Reference Green and Hobolt2008) and Buttice and Stone (Reference Buttice and Stone2012). On the spending dimension, since respondents hold a moderate position, this dynamic does not emerge as clearly.

Which attributes ultimately prevail when respondents are confronted with awkward choices? We move to this question in the next section, where we finally pull in integrity—the archetypal valence attribute.

Policy Trumping Valence in Awkward Choices

Candidates with dubious traits frequently win elections. In citizen-candidate models, this outcome results from an oversupply of low-quality candidates due to limited electoral competition or the failure of high-quality citizens to coordinate (for example, Myerson Reference Myerson1993; Caselli and Morelli Reference Caselli and Morelli2004). The ideal candidate of our typical respondent has a university education and a clean sheet, though only a middle income. Respondents also typically prefer full recognition of rights and oppose spending cuts. This candidate profile trumps all the alternatives,Footnote 15 but are respondents more likely to sacrifice valence or policy attributes when confronted with awkward choices? How do voters choose if a high-quality candidate is on offer, but his policy views are far from their ideal?

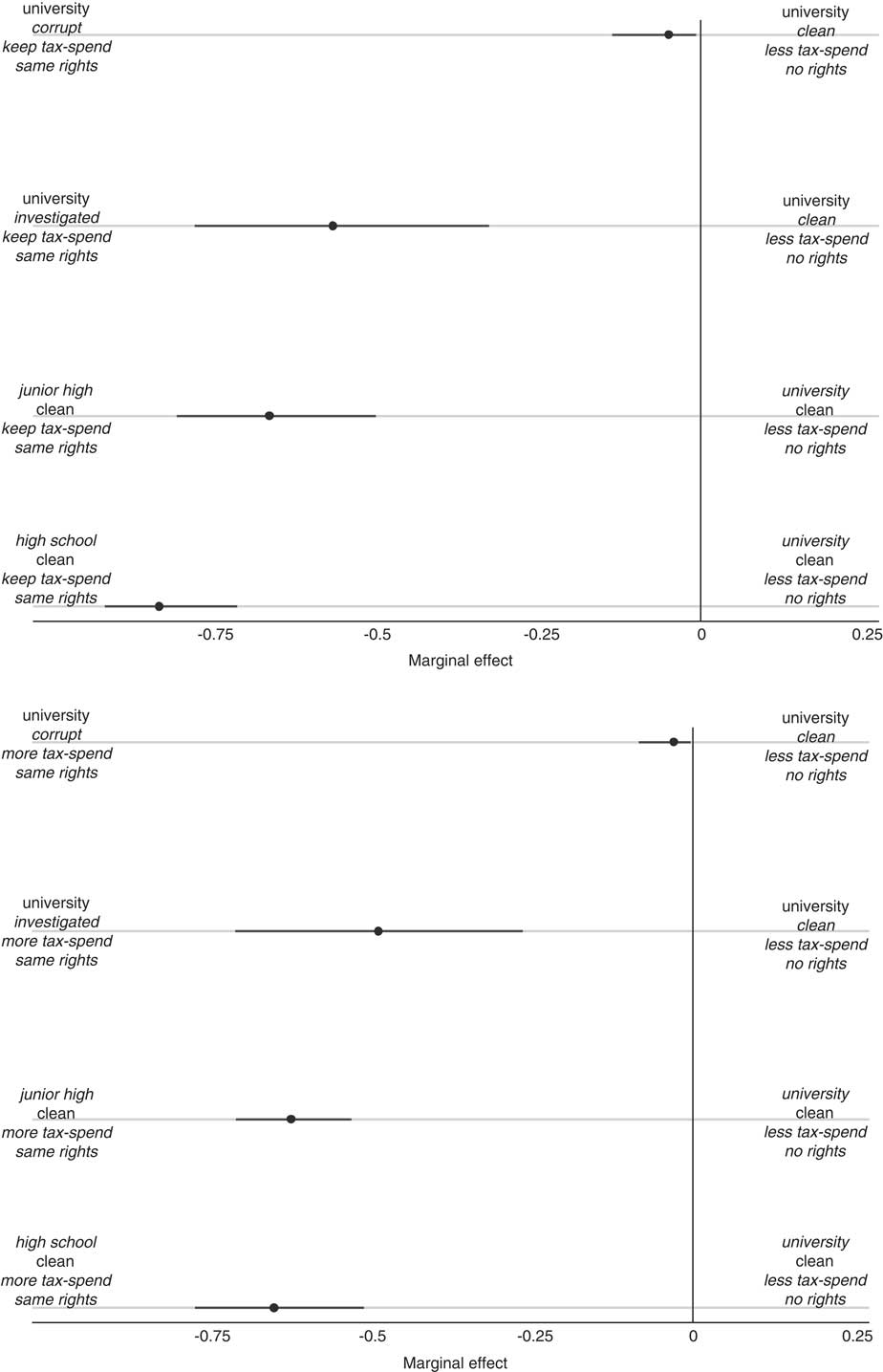

Figure 3 lists, on the left-hand side, profiles of candidates who support full recognition of rights and oppose spending cuts, but fall short in terms of valence (their educational attainment is lower or there are issues concerning their integrity). The candidates on the right-hand side are university educated and honest, but they are pro-cuts and against the recognition of rights. Figure 3 displays the marginal effects of choosing the latter candidates, given the former; in other words, the changes in the probability of preferring a high-valence candidate with different policy views over a lower-valence candidate with ideal policy views. If the marginal effect is lower (higher) than zero, respondents are less (more) likely to prefer the higher-valence candidate.

Fig. 3 Awkward choices Note: respondent with mean or modal traits, all candidates with middle income.

Policy clearly trumps valence in these awkward choices. Even in the most difficult situation of deciding between a corrupt candidate who shares her policy views and a clean one who does not, our typical respondent is between 2.9 and 4.9 percentage points more likely to prefer the corrupt over the honest (despite the fact that the respondent assigns the highest average saliency to integrity, compared to the other four attributes). These figures increase to 48.7 and 56.2 points, respectively, if the candidate is only under investigation.

Better education is even more emphatically disregarded. Respondents are between 62.3 and 82.9 percentage points more likely to prefer less-educated candidates with ideal policy views than better-educated ones with disliked policy positions.

These results hold even with left, center or (more weakly) right-wing respondents, who have political interest and saliency traits at the mode or mean value of their subsets (see Figures A7 to A9 in the online appendix). In awkward choices, centrist voters also trump valence for policy (cf. Galasso and Nannicini Reference Galasso and Nannicini2011).

Conclusion

Valence comes out somewhat tarnished from this exercise. To most scholars, it is not surprising that income is far from being perceived as an indicator of valence. We suspect that this is unrelated to the characteristics of our respondent pool, so more careful thought is required. Because high income is unlikely to be rewarded electorally (and it could even be a liability), Galasso and Nannicini’s (Reference Galasso and Nannicini2011) finding that higher-income candidates are assigned to marginal seats may be related to different selection mechanisms.

Moreover, despite being considered primarily as a simple additive component of voters’ utility, valence influences voting behavior only conditionally. Education—a plausible proxy for competence—interacts with candidates’ policies displaying traits of positive complementary, especially along the same-sex rights dimension, where our respondents hold a strong equal-rights position. In line with recent studies of voting behavior, which have found more extensive valence voting under ideological convergence (Green and Hobolt Reference Green and Hobolt2008; Buttice and Stone Reference Buttice and Stone2012), we show that the effect of university education increases as candidates’ and respondents’ policy opinions converge. Education may even be a liability for profiles that combine particularly disliked policy positions. On the spending dimension, however, our respondents take a moderate position and perhaps there is not enough ideological dispersion to allow positive or negative complementary to materialize.

Further, integrity (the archetypal valence attribute) may be ignored. Our typical respondent prefers a corrupt (but socially and economically progressive) candidate to a clean but conservative one. In other words, policy trumps valence in awkward situations, and this applies across all types of respondents, regardless of their political traits. Integrity, despite being assigned the highest mean saliency across the five attributes by most respondents, is disregarded in awkward settings.

This is not to say that, at the margin, a valence advantage is irrelevant. It may shape both citizens’ incentives to enter the electoral competition and politicians’ positioning in the policy-valence space. However, valence could indeed be relegated to the backstage in countries like Italy, which displays comparatively high levels of public dissensus on social and economic values and an appreciable association between partisan attachment and these values (see Bartels Reference Bartels2013, 50). Polarization could therefore be a fertile breeding ground for low valence politicians. In these settings, the selection of party candidates through primaries may enhance valence-based competition at the expense of policy-based competition, while selection by party elites may produce the opposite.

In conclusion, even though the similarity of some findings with the candidate conjoint experiment of Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto (Reference Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto2014) is of some comfort, these results need corroboration beyond the confined settings of an experiment. This is a worthy objective of future research.

Appendix

TABLE A1 Voting, Valence and Policy Attributes