The United Cities and Local Governments organization reported in 2007 (United Cities and Local Governments 2007) that the share of gross domestic product spent by local governments in countries in sub-Saharan Africa was only 1.8 percent while in the rest of the world it was 6.6 percent. This difference signals that there is less federalism in sub-Saharan African countries. The fact that sub-Saharan African countries score worse on perceived levels of corruption in comparison with the rest of the world is also interesting. According to Transparency International (2014), the average corruption perception index for the countries in sub-Saharan Africa in 2014 was 33 whereas the global average was 43 (the lower the index the worse). These findings are circumstantial evidence that centralization of power is correlated with more corruption.

This article investigates the incentives citizens and leaders have to behave under alternative institutional designs. The first purpose of the study is to observe whether corrupt leaders are replaced more often in federal democracies than in centralized ones. As a byproduct, I find evidence that helps to adjudicate between the somewhat conflicting findings in the literature dealing with naturally occurring data.

I tested in a laboratory setting a variant of Roger Myerson’s theory concerning how different institutional designs affect the behavior of principals and agents; in particular, the replacement of corrupt leaders by voters. However, the theory is also useful to analyze more general contexts in any organization in which power decentralization is paired with extra accountability incentives to promote good behavior. In this sense, federalism can be seen as a special case of a principal-agent model with asymmetrically divided responsibilities among agents.

In the model, two different settings are proposed to investigate how effective electoral incentives are in preventing leaders’ corrupt behavior. The first institutional design emulates a centralized democracy in which the president alone decides on the allocation of a certain amount of money; and the voter decides whether to reelect the president or not. The second design is closer to a federal democracy, in which not only the allocation of power is decentralized—there is a president and a governor—but also the voter has the ability to promote the governor to the presidency.

Different electoral incentives have distinct consequences for the success and failure of democracies. Centralized democracies can have either a good equilibrium in which leaders behave and citizens reelect them, or a bad equilibrium in which leaders are corrupt and citizens reelect them. However, federal democracies cannot have a bad equilibrium in which both the governor and the president are corrupt at the same time and still expect to be reelected. This theoretical result is supported by the data gathered in this study.

Another issue checked in this study is the effect of the language used in the experiment. Is it the case that subjects refrain from corrupt action when an action is labeled as such? Do they behave less responsively when the agency is described in neutral terms? In this study, I used neutral language to describe corrupt behavior in half the sessions and charged language in the other half. I first present the aggregated results for testing the main theory and then discuss the disaggregated findings.

I use laboratory experiments with human subjects to assess the theory. In the laboratory, we can have greater control over confounding variables and also randomly assign subjects to the political environments we investigate. Random assignment is important to equalize, in expectation, possible confounders between groups. Using an experiment allows one to hold culture and preferences constant, so that the differences in behavior can be attributed to differences in institutions, rather than differences in culture or the preferences of individuals acting in the institutions. The study is important to evaluate the differential impact of alternative constitutional designs on the behavior of citizens and leaders. This effect is relevant in determining whether a democracy succeeds or fails in preventing corruption and replacing corrupt leaders. If the behavior of citizens and leaders correlates with democratic instability, then the experimental findings I present here are important to providing a better understanding of the likelihood of democracy surviving under different constitutional designs. Beyond testing the main aspects of the theory, this study investigates certain theoretical points that are left open. For instance, when we have two possible equilibria as rational strategic choices, which one is selected by the players? Also—and in the particular case of comparison between democratic designs—is it the case that we observe less corruption in federal democracies? The theory does not make any predictions about equilibrium selection and level of corruption.

Moreover, the impossibility of running a field experiment randomly assigning constitutional designs to new democracies—or the absence of a natural experiment that does so—makes this research even more valuable. Moving onto a broader context, we can extrapolate the results to situations in which a similar set of incentives determines a principal-agent relationship. The same rational choice structure remains when we remove the substantive context introduced by the wording used in the experiment—which was done in half the sample. The results are then informative for analyzing any phenomena where there is a principal who can replace leaders by promoting others.

Finally, no value judgment between centralized and federal democracies is posited. The study provides evidence favorable to the theory.

Related Literature

This article aims to unravel a possible cause for the survival of democracies. The empirical literature has found that the survival of democracies and nations’ wealth are correlated (Przeworski et al. Reference Przeworski, Alvarez, Cheibub and Limongi2000). Looking at one institutional aspect of this problem, Linz (Reference Linz1990) claims that presidential democracies are less likely to survive than parliamentary democracies; and Cheibub (Reference Cheibub2007) argues that the opposite is true. Offe (Reference Offe2006) states that the first basic design choice of constitutional democracies is the one between federalism versus a unitary form of state. A federal system can have several aspects and serve functions other than a pure quantitative division of attributions. For example, it can serve an ethnic self-government purpose in which minorities at the national level have greater regional control in the places where they are regional majorities (Chandra Reference Chandra2008). This decentralization of power among ethnic—or maybe linguistic—groups that serves the purpose of preventing one group from imposing its way upon another can also be found in Weingast (Reference Weingast1997).

I investigate the accountability problem in the principal-agent relationship between citizens and leaders in different democratic contexts. Specifically, I ask whether extra electoral opportunities and competition brought about by federalism impact the behavior of voters and presidents. Related electoral control models—but with ex ante optimal retention strategies by the voters—can be found in Barro (Reference Barro1973), Ferejohn (Reference Ferejohn1986), and Seabright (Reference Seabright1996). For a non-technical introduction to the principal-agent theory, see Gailmard (Reference Gailmard2014). For a principal-agent theory on the retention of leaders under the context of adverse selection and moral hazard see Banks and Sundaram (Reference Banks and Sundaram1998).

Treisman (Reference Treisman2000), Serra (Reference Serra2006), and Freille and Haque (Reference Freille and Haque2007), all find federalism to be correlated with perception of greater corruption. Chowdhury (Reference Chowdhury2004), however, finds that political competition is associated with less corruption. Keeping corrupt leaders in office would then pose a threat to democratic stability. Myerson (Reference Myerson2006) analyzes the conditions under which a federalist design of the executive branch may enable a democracy to succeed.Footnote 1 He first models a centralized democracy as a benchmark and then proceeds to a federal design. A brief explanation of Myerson’s theory—through a somewhat less technical model—can be found in Myerson (Reference Myerson2011). Finally, Marshfield (Reference Marshfield2011) applies the theory to the case of South Africa.

Theory

In this study federalism means a quantitative division of power. If in a centralized democracy the president allocates a value v, in the federal case she can only allocate a fraction v/a, where a≥1, while a governor allocates the remaining amount v−v/a. I assume that the citizen’s outcome is affected by the president’s action more than by the governor’s action, that is, a<2. We may justify the assumption that the outcomes resulting from the actions taken at the presidential office are more salient to the citizen by noting the much bigger turnout rates observed in presidential elections than in gubernatorial ones.

The theory tested in this paper accounts for both federalism and competition, and unravels when corrupt presidents should have a greater expectation of reelection—under different constitutional designs. I present a variation of Roger Myerson’s game-theoretic model of success and failure of democracies (Myerson Reference Myerson2006) and derive several testable predictions from it. I then design a laboratory experiment to test those predictions. The experimental design accounts for the extra physical constraints imposed by the method. Nevertheless, to have construct validity, the experimental model is produced such that it provides the same theoretical results as the original one.Footnote 2

Myerson uses a repeated game to model the democratic process. There is a unit mass of identical voters who receive a payoff w if the leader acts responsibly and 0 if the leader acts corruptly, and pay a cost x to change the leadership. The leader is randomly selected, extracts a payoff b from office per period, but can gain c per period via corruption. The voters observe the behavior of the president and decide whether to reelect her or not. All actors have the same discount value ρ for the future. A democracy is said to be frustrated if the leader expects to be reelected with probability 1, regardless of her behavior in the office. Myerson then adds a perturbation to the model, by allowing a virtuous politician—who never acts corruptly—to be selected with probability ε>0. Theorem 1 then states that there exists a good equilibrium in which a democracy succeeds, and a bad equilibrium in which the democracy is frustrated and fails.

Theorem 1 (Myerson Reference Myerson2006): Suppose

![]() $${\epsilon}\,\lt\,x(1{\minus}\rho )/w\,\lt\,1$$

and b+c<b/(1−ρ). An equilibrium then exists where unitary democracy succeeds. But there also exists an equilibrium where unitary democracy is frustrated and fails.

$${\epsilon}\,\lt\,x(1{\minus}\rho )/w\,\lt\,1$$

and b+c<b/(1−ρ). An equilibrium then exists where unitary democracy succeeds. But there also exists an equilibrium where unitary democracy is frustrated and fails.

The first inequality is easier to understand if we rewrite it as εw/(1−ρ)<x, that is, the expected benefit from electing a virtuous leader is lower than the cost of replacing the corrupt leader. This condition enables the bad equilibrium. The second and third inequalities enable the good equilibrium by stating that the voter is better off paying the cost of replacement and then definitely having a good leader in office and that the benefit to the leader if she acts responsibly and stays in office forever is greater than the one-shot gain from corruption. A good equilibrium is given by the following strategies by the president and the voters. The voters reelect an honest president and replace a corrupt one; the president acts responsibly whenever she gets to play. No player has an incentive to unilaterally deviate from these strategies. The voters obtain w/(1−ρ), which is a global maximum in this game, and the president obtains b/(1−ρ), which is better than her one-shot deviation payoff given in the second inequality. To construct a bad equilibrium, suppose the president’s strategy is to extract the benefit form office plus the extra rent from corruption, no matter what the voters choose. The best response of the voters is to reelect the leader, given the first inequality. But if the voters are reelecting the president, then because of the third inequality the president’s best response is to extract the extra payoff from corruption.

Myerson captures federalism with a similar model but with a national level and a provincial level with governors elected by the voters. Also, the voters can promote a governor to the presidency. The occupant of the presidential office gains b 1 per period from office and can receive an extra c 1 per period from corruption. The occupant of the gubernatorial office gains b 0 per period from office and can obtain extra b 0 per period from corruption. We assume b 1+c 1<b 1/(1−ρ) and b 0+c 0<b 0/(1−ρ). Furthermore, Myerson assumes that b 1>b 0+c 0, that is, the gain of the presidential office alone is bigger than the gain b 0 from the gubernatorial office plus the c 0 that can be extracted via corruption at this lower office. The voters receive w 0 from having an honest governor in office and w 1 from having an honest president in office. If a leader acts corruptly in office then the voters receive 0 from that office in that period.Footnote 3

Theorem 2 then states that democracy cannot be frustrated at both national and provincial levels. Myerson finds that there are equilibria in which both levels of democracy succeed, and equilibria in which a single level frustrates, but no equilibrium in which both levels are frustrated.

Theorem 2 (Myerson Reference Myerson2006): In any sequential equilibrium of federal democracy, as long as there is a provincial governor who has not yet acted corruptly, democracy cannot be frustrated at both the national and provincial levels.

An intuition behind the proof of the theorem is as follows. Suppose there is a corrupt president and an honest governor who are kept in office by the voters no matter what they do. Democracy is then frustrated at both levels. The best response of the governor, after observing that the voters are not replacing a corrupt leader, is to stop acting responsibly. But if the governor is acting responsibly then the voters know that that governor is a virtuous type of politician. Hence, the voters are better off swapping the president for the governor. But then the president cannot expect to be reelected with probability one regardless of her behavior in office. Therefore, democracy cannot be frustrated at the national level, which is a contradiction as we assumed frustration at both levels.

This interesting result demonstrates the theoretical superiority of a federal democracy design compared with a centralized democracy. We have the impossibility of mutual frustration with the federal constitution. However, we cannot observe expectations and so the aim of this paper is to derive and test a few falsifiable predictions from theory. These predictions are stated in the next section with a description of the experimental design used to generate the data.

It is noteworthy that these games can have many equilibria, but point predictions are not the goal of this study. I am more interested in, first, observing whether the theory’s “impossibility” result about federal democracies is corroborated with experimental data, and second, in which equilibrium emerges, if any, in the centralized democracy.

Experimental Design

The following games are modified versions of Myerson’s models for the centralized and federal democracies. The motivation for these new models is an attempt to assess the theory by designing games that can be implemented in the laboratory. This task is not possible with Myerson’s games due to the physical restrictions imposed by the laboratory, such as limitations on the number of participants. The new models take this restriction into account.

The original models have a continuum of voters and an infinite number of candidates. In the laboratory games, I have one voter and one subject candidate for each office. This solution seems reasonable because the voters and candidates in the original models are representative ones—they all have the same preferences according to their roles in the games.

Even though financial incentives are provided to the subjects, there is always the risk of having the participants playing without worrying about the financial consequences of their choices. Therefore, in the centralized democracy game, the experimental design is such that there are only two subject players, a voter and a candidate. In the federal democracy game there is one candidate for president, one candidate for governor, and one voter.

To make it possible to replace presidents and governors, the experiment uses artificial players, or robots. These robots make particular moves. They always make the same choices according to their type. There is an unlimited number of such “politicians.” The choices the subjects make and the election probabilities of the artificial types are common knowledge, but the voter does not know whether there is a human subject in office or an artificial one.

It is important to recall that the simplification brought about by the model helps the relationship among the variables in the model, holding everything outside the model constant. A model does not say that the variables included are the only ones that matter. A model says little or nothing about the variables external to it. Nevertheless, a model can enlighten the relationship among the variables, and laboratory experiments are well suited to assess deviations from models, as well as to adjudicate between antitheses brought about by models.

Centralized Democracy

The roles subjects can play are a voter and a candidate for president. I also use two kinds of artificial players. These are intrinsically virtuous or corrupt politicians, played by the computer. The presidents played by the participants are called human, to contrast with the artificial players.Footnote 4 For presentation purposes, I use female pronouns for the president and male pronouns for the voter.Footnote 5 The roles remain the same throughout the game, that is, the candidate cannot become the voter and the voter cannot become the candidate.

The timing of the game is as follows: if the human politician has never been previously selected to the office, then she is selected with probability 1−ε and a virtuous politician is selected with probability ε, where ε=0.1. If the human politician was ever selected to the office and then replaced, a virtuous politician is selected with probability ε, and a corrupt politician is selected with probability 1−ε. Note that the human politician who is replaced stays out of the game until it ends. If a virtuous politician is selected then b is chosen. If a corrupt politician is selected then b+c is chosen. Whenever in office, the human president chooses between being honest and being corrupt. If she decides to be honest then she receives solely the payment b=1 from the office. If she chooses to be corrupt, she then extracts a fixed extra rent c=1 from corruption and obtains b+c=2 in that period. The voter observes the choice. If the president acts responsibly, then the voter earns w=1, otherwise he earns 0. If he chooses to replace the president, he pays x=1. If the human president was kept in office, she makes a new choice between b and b+c. The game continues to another period with probability ρ=0.85. All actions are observed by all players.

Federal Democracy

The subject players are a voter, a candidate for governor, and a candidate for president. There are also the virtuous candidates for governor, the virtuous candidates for president, the corrupt candidates for governor, and the corrupt candidates for president. The presidents and governors played by the participants are called human. I use female pronouns for the president and the governor and male pronouns for the voter. The president now chooses between acting responsibly—receiving b 1—and acting corruptly—receiving b 1+c 1—, where b 1=c 1=0.7. The governor chooses between honesty—gaining b 0—and corruption—gaining b 0+c 0—, where b 0=c 0=0.3. The voter can replace one leader, both, or neither and can also promote the governor to presidency. The president and governor replacements cost x 1=0.7 and x 0=0.3, respectively. All actions are observed by all players.

If the human politician—the one played by a participant in the experiment—has never been previously selected to her respective office, then she is selected with probability 1−ε and a virtuous politician is selected with probability ε=0.1. If the human politician was ever selected to her office and then replaced, a virtuous politician is selected with probability ε, and a corrupt politician is selected with probability 1−ε. Note that the human politician who is replaced stays out of the game until it ends. If a virtuous president is selected then b 1 is chosen. If a corrupt president is selected then b 1+c 1 is chosen. If a virtuous governor is selected then b 0 is chosen. If a corrupt governor is selected then b 0+c 0 is chosen. The selected leaders then choose between b and b+c—the president chooses between b 1 and b 1+c 1, and the governor chooses between b 0 and b 0+c 0. The players observe the choices. If the governor acts responsively, then the voter earns w 0=0.3, otherwise he earns 0 from the provincial level. If the president acts responsively, then the voter earns w 1=0.7, otherwise he earns 0 from the national level. If he chooses to replace the governor, he pays x 0=0.3; if he chooses to replace the president he pays x 1=0.7; if he chooses either to replace both or to promote the governor to presidency he pays x 0+x 1=1. If a human president was kept in office then she makes a new choice between b 1 and b 1+c 1. If a human governor was kept in office then she makes a new choice between b 0 and b 0+c 0. The game continues to another period with probability ρ=0.85.

Predictions

Even though the laboratory imposes further restrictions on the theory, with these games Theorems 1 and 2 still hold. The introduction of the corrupt type does not alter the theoretical predictions. The experimental design adopted in this study preserves the premises of Theorems 1 and 2, thus the Bayesian updating for the relevant situations is the same. Supplemental Online Appendix 2 provides two propositions and their respective proofs as a more theoretically rigorous treatment of the issue. The only extra imposition I make on the parameters is that w 1/(1−ρ)>x 0+x 1.

Prediction 1: Voters are going to reelect presidents who act corruptly less often in federal democracies than in centralized democracies.

Prediction 2: Given that the games in the laboratory emulate nascent democracies, the candidates have not yet had time to establish positive reputations, therefore the bad equilibrium in which presidents act corruptly and are reelected is expected to emerge in the centralized democracy.

Prediction 3: In a stable democratic context, the good equilibrium in which presidents act responsibly and are reelected is expected to emerge empirically, even in the centralized design.

Prediction 4: Presidents who act responsively are going to be reelected at the same rate in both institutional designs.

Prediction 5: Governors who act corruptly are going to be replaced less often than corrupt presidents in federal democracies.

Prediction 1 comes straightforwardly from Theorem 2. In federal democracies the voter has the power to promote a governor to the presidency. This ability, together with the occurrence of a good governor, makes the swap rational for the voter. Also, the possibility of being promoted brings an extra incentive for the governor to behave in office. Therefore, it is reasonable to expect the replacement of presidents who act corruptly to be replaced by governors who act honestly, which should make replacing presidents who act corruptly more frequent in the federal design than in the centralized one. In the centralized case, the voter and the president do not have the extra electoral combination of incentives brought about by the existence of a governor.

Predictions 2 and 3 are labeled as predictions solely for the sake of presentation. They are not predictions in the sense that either one of the two is expected to occur. One of the strengths of the use of laboratory experiments is the possibility of adjudicating between competing claims. The theory allows for both good and bad equilibria. In the lab we can find either one to be true or neither to be true, but not both to be true.

Prediction 4 is immediate from theory and helps to check rationality and compliance among subjects.

Prediction 5 is based on the fact that governors do not face the same pressure they themselves impose on the presidents. The voters must face governors as they face presidents in centralized democracies. But it is less costly to replace presidents in federal democracies, in expectation, due to the existence and observation of good governors.

Experimental Sessions

The experiment was conducted at the Center for Experimental Social Science, New York University. There were 17 sessions with a total of 114 undergraduates. This sample produced 2805 data points. The anonymity of the participants’ actions was ensured in the recruitment and in the experiment instructions. As the subjects arrived, their identity was checked and they were assigned to computer terminals. Once everyone was accommodated, they read and signed the consent form. Afterwards, the instructions for the first game were read aloud and the subjects followed with their own instruction sheets. The instructions for the second game were read after the end of the first game. In the first seven sessions subjects played the centralized democracy game first and the federal democracy game second. In last six sessions they played the federal democracy first and the centralized democracy second. Subjects received an $8 show up fee plus the money they earned in both games. On average subjects earned $27. The sessions lasted less than 1 hour each. The entire experiment complied with the Institutional Review Board rules for experiments conducted at the home institution’s laboratory. The games were programmed in z-Tree (Fischbacher Reference Fischbacher2007).

Results

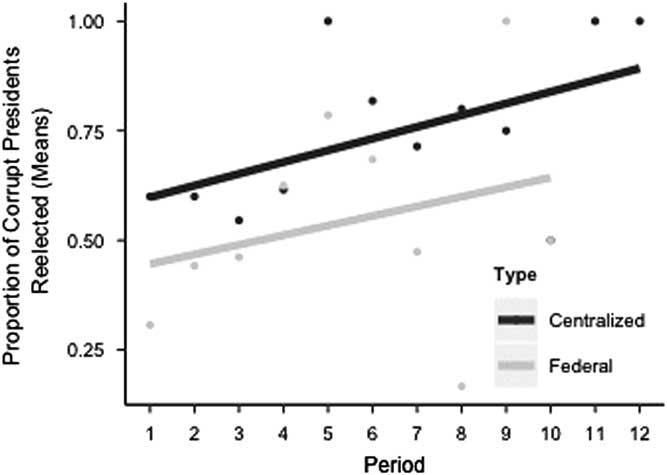

I found support for Prediction 1.Footnote 6 The ratio of reelection of presidents who acted corruptly in centralized democracies is 0.67 against only 0.47 for federal democracies. This difference is significant in substantive and statistical terms. A two-sample test for equality of proportions rejects the null hypothesis that the proportions are equal (χ 2=8.24, df=1, p-value <0.005).Footnote 7 I also estimated a logistic regression of replacement of corrupt presidents on constitutional design. The results can be found in Table 1, column 1. The coefficient of centralized democracies in column 1 indicates that corrupt presidents in centralized democracies are replaced less often than corrupt presidents in federal democracies. This result is statistically significant at the 0.1 percent level. The dynamic relationship between corruption and reelection over time, disaggregated by the type of democratic environment, can be seen in Figure 1. Periods in the experiment are measured along the horizontal axis and the proportions mean of corrupt presidents reelected is measured along the vertical axis. The gray circles indicate federal democracies and the black circles indicate centralized democracies. The lines indicate the linear probability model estimates. The figure shows that the rates of reelection of corrupt presidents are greater in centralized democracies than in federal ones across periods.

Fig. 1 Reelection of corrupt presidents per period

Table 1 Logistic Regressions on Constitutional Design

Note: *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001.

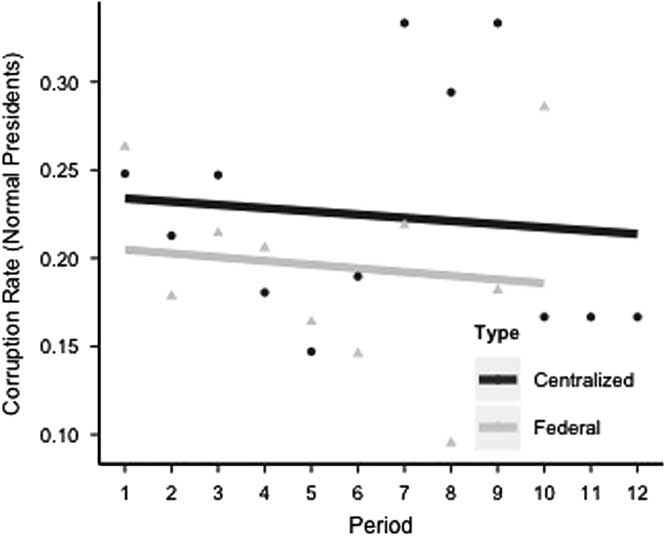

Human presidents in the centralized design acted responsibly 60 percent of time; and human presidents who acted honestly were reelected 99 percent of time. These numbers suggest that the good equilibrium was selected by subjects while playing the centralized democracy game. This result provides evidence in favor of Prediction 3 against Prediction 2. The reelection rate of honest presidents in federal democracies was 97 percent, which confirms the expectation in Prediction 4. A logistic regression of corruption on democracy type can be found in Table 1, column 2. The coefficient’s sign of centralized democracies indicates that presidents in centralized democracies misbehaved more often than presidents in federal democracies in this experiment. Moreover, the coefficient’s size and standard error show that the difference is significant in substantive and statistical terms. Figure 2 shows the rate of human presidents acting corruptly, separated by type of democracy. Periods in the experiment are measured along the horizontal axis and the corruption rates are measured along the vertical axis. The gray circles indicate federal democracies and the black ones indicate centralized democracies. The lines are linear probability model estimates. The figure shows that human presidents in federal democracies were, on average, less corrupt than human presidents in centralized democracies.

Fig. 2 Proportion of human presidents acting corruptly per period

Finally, the data does not support Prediction 5 in statistical terms, but the reelection rates are as expected. The percentage of corrupt presidents replaced in federal democracies is 53 percent while the percentage of corrupt governors replaced is only 45 percent; however, this difference is not statistically significant (χ 2=1.24, df=1, p-value=0.27).

Discussion

This section addresses possible concerns regarding the experimental design choices and their results.

One possible concern with the experimental design in question is the way participants Bayesian update their beliefs during the games and how this could this affect an assessment of the theory. In the theory, there are only two types of politicians: normal and virtuous. In the experiment there are three types of politicians: human, virtuous, and corrupt. The introduction of that third type is necessary due to the fact that a human politician who is replaced stays out of the game for the remaining periods. If there were no corrupt politicians, then the voter would know with certainty that a virtuous politician would follow a human one after the human politician was replaced.

Alternative experimental designs that do not require the use of corrupt types are possible. Designs with multiple subjects playing the role of candidates prevent the necessity of adding that third type. However, arguably worse problems arise with these alternative games. One issue is having subjects not participating at all in the experiment. If there were many candidates it is likely that some of them would never be selected for office. This non-participation is problematic because subjects could become frustrated. As a consequence, subjects’ attention to the experiment could decrease, and when selected to play after a long period of waiting, their behavior could be impacted and the quality of the data would be compromised. Also, that frustration experienced in the experiment could harm the good reputation laboratories must preserve for promoting engaging experiments. Another problem could arise if there were more than on candidate, but not many of them. In that case, the candidate would know that she would be (re)selected to office in a matter of a few periods. This likelihood of repeated participation would create an expectation of the corrupt action being more profitable. Moreover, all these alternative experimental designs depart from the theory, which assumes that there is an infinite number of candidates and that politicians who served and were replaced stay out of the game until the game ends. Finally, in both alternative designs there is a loss of sample size power because there are fewer experimental units per session.

A second issue is the human–computer interaction. Is it the case that voters treat computer and humans differently? Even though the voter’s payoff is not dependent on who is the other player, given the same actions, one could argue that a human would be less willing to make a decision that would cause “harm” to another human, even if this choice comes at a cost. The results show that voters behaved somewhat differently when a robot was playing. In the centralized design corrupt robots were reelected 13 percent of time and human participants who did not played responsively were reelected 63 percent of time. The difference is statistically significant (χ 2=5.01, df=1, p-value=0.02). In the federal case, the reelection percentages after corruption were 11 for robots and 46 for humans; and this difference is marginally statistically significant (χ 2=2.61, df=1, p-value=0.10). It should be noted that in both constitutional designs voters reelected human players more often than robot players, in accordance with the intuition.

In spite of the issues above, note that the main point of the theory relies on the instance where a governor has never been corrupt. In this particular case, the Bayesian update for the citizen is the same regardless of who is playing the incumbent governor—be it another participant or the computer. The voter cannot know whether the governor is a participant or the computer if the same honest decision is always made. The instances where the voter knows whether a human is in office are outside the conditions assumed in Theorem 2. Finally, if we observe a governor who has always acted responsively, the period in which the voter promotes her to the presidency is not important, since the equilibrium concept is that of a sequential one. Whenever the conditions are satisfied, the Bayesian updated belief is only ever the same, regardless of who is playing the governor.

Another reason for concern is the language used in the experiment. One could argue that using a negatively charged word such as “corruption” could induce some behavior that a neutral word might not. This argument makes sense but is not a threat to the experiment because the language was homogeneous across the groups. Note that the purpose of the experiment is to compare two institutional designs, and not measure the level of corruption in a particular type of democracy per se. If the concept of corruption-induced behavior in the centralized democracy it is reasonable to expect that the concept induced the same behavior in the federal democracy. In order to clarify this issue, a neutral language was used in half the sessions. The results show that people do not behave differently according to the language used. In the centralized democracies human presidents acted corruptly 38 percent of time when the language was neutral and 43 percent of time when the word corruption was used to describe their choices. In the federal democracies, human presidents acted corruptly 27 percent of the time in the context-free design and 23 percent of the time in the context-rich case. None of these differences were found to be statistically significant (the respective p-values are 0.63 and 0.56). Two logistic regression models that control for the type of language used were estimated and can be found in Table 1, columns 3 and 4. In column 3 the model controls for the type of language. The coefficient shows that there is no difference regarding the use of neutral or negatively charged language. In column 4, an interaction term of democracy type and language type was added to the previous model. This interaction term, too, is not significant.

One last concern to be dealt with is the fact that in some specific situations the voter in the experiment can be sure about what type of player is in the presidency. For example, if a president who was kept in office makes a decision different from the previous one, then the voter can be positive that it is a human president. Because of that situation, the relative expected cost of replacing a president is lower in federal democracies than in centralized democracies. This issue, however, did not drive the results in the experiment. The cost difference stated above is only $0.015, which should be too small a quantity to be salient in the experiment. In spite of that, I ran one session in which the relative cost of replacing a president in a federal democracy was greater than the replacement in centralized democracies. The reelection rates of corrupt presidents in the main treatment for federal democracy and in the costlier federal democracy are essentially the same. In the main treatment corrupt presidents were reelected 46.9 percent of the time and in the costlier case corrupt presidents were reelected 44.4 percent of the time.

Conclusions

In this paper, I test a theory on decentralization of power among agents and electoral incentives against corruption. In other words, I investigate how a federal democratic institutional design compares with a centralized democratic institutional design. In order to perform this task I borrow a theory from Myerson (Reference Myerson2006) and present a simplified version of the model with some additional assumptions. These impositions are brought about by the method—laboratory experiments—I use to generate the data. The new model nevertheless allows the derivation of the same theorems as in the original one. I then extract falsifiable predictions from it to test against the data.

Taken together, the results provide evidence in favor of the theory with respect to citizens holding leaders accountable. In the data, voters do reelect corrupt leaders more often in centralized democracies than in federal democracies; select the good equilibrium even in centralized democracies; and reelect honest presidents at the same rate in both institutional designs. All these findings are substantive and statistically significant. Voters also replace corrupt governors less often than corrupt presidents in federal democracies, although that difference was not found to be statistically significant. Finally, the federal democracy prevented corrupt behavior more than the centralized democracy did.

One possible avenue for further investigation is to test related models. For example, Svolik (Reference Svolik2013) presents a similar model in which the assumption about perfect observation of corruption is relaxed. In that article, Svolik argues that when voters do not perfectly observe corruption they must be willing to pay an extra cost to acquire information on the leader’s behavior in order for the good equilibrium emerge.

We would rather democracies succeeded than failed. This study tries to help us with this goal. It is an attempt to provide empirical evidence for a theory concerned with institutional design, which might affect the sound continuation of democracies. The investigation about what is the best form of government may inform critical constitutional choices. This research agenda is important, for instance, to inform the everlasting debate about the virtues and vices of federalism. However, the research agenda is also important for two other reasons: (i) over the past two decades some 20 countries have been recognized as sovereign states and (ii) new states in the contemporary world are more likely to have constitutions than not. The decision regarding the decentralization of power is, from the outset, a constitutional one, and one that is likely to influence the success or failure of new democracies. In a world in which wars are redefining states—and killing thousands of civilians in the process—the stability and success of new democracies are our best hope to avoid that path.