There is a large gender disparity in representation among elected officials in Japan. As of 2017, the share of seats held by women in the Diet—the national parliament of Japan—is only 13.7 percent despite the fact that a majority of the population are women. The number of women running for office is increasing rapidly after the introduction of a mixed electoral system in 1994, in response to changes in electoral incentives and party strategies (Gaunder Reference Gaunder2009; Gaunder Reference Gaunder2012).Footnote 1 In the 2017 lower house election, the share of female candidates hit a record high number (17.71 percent) since 1945. Yet, the share of seats held by female parliamentary members is still the lowest among the countries of the Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD), whose average is 28.8 percent.Footnote 2 The gender imbalance among elected officials is an important issue because the under-representation of women in politics may exert a great influence on legislation and policy outcomes (Dollar, Fisman and Gatti Reference Dollar, Fisman and Gatti2001).

To explain such an immense disparity in representation between men and women in Japan, a number of studies have focused on the short supply of female candidates.Footnote 3 Yet, the under-representation of women can be also attributed to the weak demand of voters for female candidates (Kawato Reference Kawato2007; Krook Reference Krook2010). A prominent explanation for this is that Japanese voters have strong norms about the gender roles of men and women in society, which leads them to exhibit strong negative biases against female candidates. Indeed, there exist sharp gender discrepancies in wages, employment status, and occupational roles in Japan (Brinton Reference Brinton1993). While these differences may not be simply the product of a strong gender-role ideology, prevailing gender roles in any given society has a potential to affect voter decisions in elections. For instance, men are frequently seen as having more leadership skills than women, and almost 30 percent of the people in Japan believe that men make better political leaders than women do.Footnote 4 These voters are likely to make inferences based on a candidate’s sex when they evaluate candidates running in elections.

Among scholars of gender and politics, there is a considerable debate about the extent to which gender stereotypes affect voter decision-making. While scholars generally agree that voters view candidates through the perspective of gender stereotypes (Lynch and Dolan Reference Lynch and Dolan2014), it remains an open question whether candidates stand to benefit from behavior or posturing that follows or deviates from their gender stereotypic image. Some scholars argue that gender stereotypes have no effect on voters (Brooks Reference Brooks2013) and that voters are influenced by party and issues cues more than gender stereotypes and candidate sex (Thompson and Steckenrider Reference Thompson and Steckenrider1997; Matland and King Reference Matland and King2002; Anderson, Lewis and Baird Reference Anderson, Lewis and Baird2011; Hayes Reference Hayes2011; Dolan Reference Dolan2014a; Dolan Reference Dolan2014b).Footnote 5 In contrast, others claim that gender stereotypes frequently matter in the evaluation of female candidates among voters, but in two opposite directions. The first line of research argues that feminine traits can be an asset for female candidates because voters punish those who do not play socially expected gender roles (Iyengar et al. Reference Iyengar, Valentino, Ansolabehere and Simon1996; Eagly and Karau Reference Eagly and Karau2002; Herrnson, Lay and Stokes Reference Herrnson, Lay and Stokes2003). The second line of research, on the other hand, argues that female candidates who conform to feminine traits suffer in elections because voters value masculine traits more than feminine traits in elections (Lawless Reference Lawless2004; Ditonto, Hamilton and Redlawsk Reference Ditonto, Hamilton and Redlawsk2013; Dolan, Deckman and Swers Reference Dolan, Deckman and Swers2015). Some even find that female candidates sometimes gain with masculine traits (Holman, Merolla and Zechmeister Reference Holman, Merolla and Zechmeister2011; Holman, Merolla and Zechmeister Reference Holman, Merolla and Zechmeister2016; Bauer Reference Bauer2017), though they can also face a backlash from voters for breaking with masculine stereotypes (Krupnikov and Bauer Reference Krupnikov and Bauer2014).

Our study contributes to the debate about whether candidates are rewarded or punished when they deviate from their gender-based behavioral expectations by conducting a conjoint survey experiment in Japan. This is especially puzzling in the context of Japanese politics given that not only gender stereotypical female politicians but also counter-stereotypical female politicians (such as Tomomi Inada, who served as defense minister under Abe’s administration) are becoming more salient. Yet, few studies have examined the effect of gender stereotypes on voter decisions outside the context of Western institutions and social norms. Moreover, the research methods employed in this study enables us not only to jointly vary many more candidate attributes than have previous experimental studies on gender stereotypes but also to observe the effect of candidate gender interacting with various other candidate attributes, including those with gender-based expectations and stereotypes, such as personality traits, issue specialization, and ideology.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. In the next section, we provide an overview of how gender-based behavioral expectations and stereotypes have been discussed in the literature on women and elective office. Following this, we explain the details of our research methods and treatment components, prior to presenting the results of our conjoint experiment in Japan. Finally, we conclude this paper with discussions for further research.

Gender stereotypes and elective office

Existing research has shown that voters typically view candidates from a gendered perspective (McDermott Reference McDermott1997). Although voters do not necessarily assign feminine attributes to female candidates (Brooks Reference Brooks2013; Dolan Reference Dolan2014a; Dolan Reference Dolan2014b; Schneider and Bos Reference Schneider and Bos2014; Bauer Reference Bauer2015), scholars have identified the existence of several gender-based stereotypes among voters in areas such as personality traits, issue positions, and ideology (Lynch and Dolan Reference Lynch and Dolan2014). First, voters tend to presume that candidates have different personality traits as conditioned by their gender (Fridkin and Kenney Reference Fridkin and Kenney2011). Female candidates are not only viewed as being more compassionate and honest than are male candidates, but they are also perceived to lack masculine personality traits, such as legislative competence and strong leadership, which are viewed as keys to success in politics (Alexander and Andersen Reference Alexander and Andersen1993; Huddy and Terkildsen Reference Huddy and Terkildsen1993a; Huddy and Terkildsen Reference Huddy and Terkildsen1993b; Lawless Reference Lawless2004).

Second, voters are considered to view male and female candidates as having different areas of issue specialization. The literature on gender stereotypes has demonstrated that the public views male candidates as having better abilities to deal with issues such as national defense, foreign policy, crime, and the economy; in contrast, female candidates are thought to be more effective in policy areas such as education, social welfare, and environmental issues (Alexander and Andersen Reference Alexander and Andersen1993; Huddy and Terkildsen Reference Huddy and Terkildsen1993a; Huddy and Terkildsen Reference Huddy and Terkildsen1993b; Koch Reference Koch1999; Sanbonmatsu and Dolan Reference Sanbonmatsu and Dolan2009; Dolan Reference Dolan2010).

Third, gender-based expectations among voters also exist in the ideological placement of political candidates. Not only are female candidates thought to be interested in different policy areas than male candidates, they are also considered to have different attitudes toward policy issues than their male counterparts (Sapiro Reference Sapiro1981; Koch Reference Koch2002). Female candidates, in particular, tend to be viewed as more liberal and progressive than their male counterparts (McDermott Reference McDermott1997; Koch Reference Koch2000; Koch Reference Koch2002). Furthermore, the distinct ideological positions of candidates between men and women are typically observed in their attitudes toward social, economic, and military issues (Jost, Federico and Napier Reference Jost, Federico and Napier2009; Verhulst, Eaves and Hatemi Reference Verhulst, Eaves and Hatemi2012).

The findings of these studies are drawn from the context of American politics. Some might be concerned that gendered perceptions among voters in the United States may not be applicable to other countries, or to Japan in particular. However, similar gendered perceptions to those found in the United States have been identified in Japan. For instance, according to the results of the 2005 national survey on gender roles in the society, Japanese voters are inclined to respond that female politicians are interested in issues such as women’s rights, social welfare, education, and the environment, and that they are more ethically disciplined than male politicians (Aiuchi Reference Aiuchi2007).Footnote 6 These similarities are partly attributed to the political environment shared between the two countries. The cross-national studies on gender stereotypes in non-American contexts demonstrate that prevailing gender stereotypes varies depending on political factors such as the use of gender quotas, the level of women’s legislative representation, and the level of economic development (O’Brien and Rickne Reference O’Brien and Rickne2016; Smith, Warming and Hennings Reference Smith, Warming and Hennings2017). Since Japan shares these important features with the United States, the extent to which Japanese exhibit similar gender stereotypes as Americans can be relatively high.Footnote 7 Thus, the research conducted on gender in politics in the United States is relevant to the context of Japanese politics as well.

Research design

We employ experimental methods in order to assess the effect of candidates’ deviations from gender-based expectations along multiple dimensions on voter evaluation. This is mainly because it is difficult to empirically examine the independent effect of gender stereotypes by using actual election outcomes due to multiple confounding factors that play into election outcomes. For instance, gender stereotypes among voters may affect how candidates formulate their electoral campaign strategies (Kahn Reference Kahn1996; Schaffner Reference Schaffner2007). Similarly, selection bias may also exist to the extent that the quality of emerging female candidates differs from their male counterparts (Lawless and Pearson Reference Lawless and Pearson2008; Fox and Lawless Reference Fox and Lawless2010; Anzia and Berry Reference Anzia and Berry2011). These potential issues make it difficult to construct causal inferences from election outcomes.

Some of the existing studies on gender stereotypes have employed experimental methods to address these concerns. These studies manipulate campaign advertisements (Iyengar et al. Reference Iyengar, Valentino, Ansolabehere and Simon1996; Fridkin, Kenney and Woodall Reference Fridkin, Kenney and Woodall2009) or newspaper articles (Kahn Reference Kahn1994; Brooks Reference Brooks2013) to understand the effect of gender stereotypes on voters’ evaluation of candidates.Footnote 8 They contribute much to our understanding by maintaining a high degree of verisimilitude and using close-to-real campaign advertisements or newspaper articles in a controlled experimental setting, but there still exist some important limitations. For instance, they rely on a small number of treatment components and manipulate only a few candidate attributes at a time, even though multiple dimensions exist in the gender-stereotyped assessments of electoral candidates among voters (Lynch and Dolan Reference Lynch and Dolan2014). As a result, we cannot fully compare the effects of multiple treatment components as well as the interactive effects of these components under their experiment framework.

In this study, we specifically conduct a conjoint survey experiment that asks respondents to review the profiles of two hypothetical candidates that are randomly generated from the set of attributes and then to choose between them. Multiple attributes of those candidate profiles are jointly varied in the experiment. This design has numerous advantages (see Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto Reference Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto2014) and desirable properties for making causal inferences about the effects of candidate sex on voter evaluation (see the Appendix). For this study, it is particularly important that conjoint experiments allow us to estimate the interaction effects of multiple treatment components in candidate evaluation, because we are interested in whether the same traits could have different effects on voter choice depending on candidate sex.

In our conjoint experiment, we focus on seven attributes of candidates for the House of Representatives in the Diet. These attributes used to describe their profiles include a candidate’s sex, education level, personality traits, issue specialization, ideological placement on social issues, ideological placement on economic issues, and ideological placement on military issues. We, however, did not include a candidate’s party label in our candidate profiles in order to minimize the possibility of creating implausible combinations, even though partisan cues may also interact with other attributes related to gender stereotypes (Sanbonmatsu and Dolan Reference Sanbonmatsu and Dolan2009; Schreiber Reference Schreiber2014). In Japan, more than four major parties field their candidates to compete for seats at the national level. If we employ a candidate’s party label as well as policy positions, many profiles become implausible. For instance, in the context of Japanese politics, it is highly unrealistic for a communist party’s candidate to hold a very conservative position on military issues. To avoid such cases while, at the same time, controlling for the effect of partisan cues, we instead asked our respondents to assume that each pair of hypothetical candidates is running with the nomination of the same party (without specifying any party’s name) in the upcoming election.

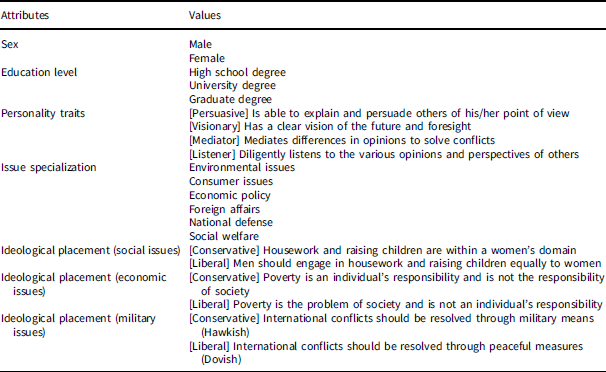

There are multiple values in each candidate attribute, and candidate profiles are created by taking one of these values, respectively. Table 1 summarizes the values of these seven varying attributes. Among these seven attributes of candidates, the first two describe a candidate’s background: sex (male or female) and education level (high school, undergraduate, or post graduate). The latter five attributes—personality traits, issue specialization, and three dimensions of ideological placements—are created in line with the existing literature on gender stereotypes and the findings from the Japanese case. In the following, we explain the values for each of these gender-stereotyped attributes in candidate profiles.

Table 1 Attributes for Candidate Profiles in Conjoint Experiment

Note: This table shows the attributes and attribute values that are used to generate the candidate profiles for our conjoint experiment.

First, to examine the interaction effects between candidate sex and personality traits, we use the following four types of personality traits about leadership styles that reflect gender role stereotypes in the decision-making process: visionary, persuasive, mediator, and listener. The first two represent masculine traits, and the latter two represent feminine traits. According to psychological studies, people are inclined to think of male leaders as having a task-oriented style that focuses on the achievement of their own goals, while female leaders hold a relationship-oriented style that emphasizes the importance of participatory decision-making processes (Eagly and Johnson Reference Eagly and Johnson1990; Konrad, Kramer and Erkut Reference Konrad, Kramer and Erkut2008). The results of a survey of nearly a thousand local politicians in Japan shows that male politicians indeed tend to rank the first two task-oriented traits—visionary and persuasive—more highly as being important for being successful politicians than do female politicians; in contrast, female politicians are prone to value the latter two relationship-oriented traits—mediator and listener—more highly than do their male counterparts (see Ono and Yamada Reference Ono and Yamada2015).Footnote 9

Second, to examine the effects of gender-stereotyped issue specializations among candidates on vote choice, we employ the following six policy areas as varying values in a candidate attribute that describes his or her issue specialization: national defense, foreign policy, economic policy, social welfare, environmental issues, and consumer issues. For each candidate, we randomly select one of the six areas and present it as the candidate’s area of focus and expertise in the profile without mentioning his or her specific position on that issue. In the context of Japanese politics, the first three are so called “traditionally male” issues, and the latter three represent “traditionally female” issues. The choice of these six policy areas is based on a pre-election survey of candidates running for the Japanese National Election in 2009 (UTokyo-Asahi Survey). According to the results of this survey, female candidates, in contrast to their male counterparts, are found to be less likely to consider foreign affairs and economic issues as important; they instead value education and environmental issues more than their male counterparts (Ono Reference Ono2015). Furthermore, one of the most politically successful women’s groups in Japan is indeed the Seikatsusha Network, which evolved from a consumer-oriented social movement (Gelb and Estevez-Abe Reference Gelb and Estevez-Abe1998).

Third, we vary a candidate’s ideological placement on social, economic, and military issues. On each issue, we present either one of the two sides to describe the ideological position of a candidate in our conjoint experiment. The descriptions were prepared by modifying the statements used in some survey questions that asked Japanese voters and candidates to reveal their attitudes on these issues. Two distinct positions on gender roles is employed to describe the political spectrum on social issues—(1) men should engage in housework and raising children equally to women and (2) housework and raising children are part of a women’s domain. We include this issue because a traditional norm about the gender-based division of labor is persistent in Japanese society (Yamamoto and Ran Reference Yamamoto and Ran2014). As the political spectrum on economic issues, we use two positions on social welfare—(1) poverty alleviation should be treated as a societal responsibility rather than an individual’s personal responsibility and (2) poverty alleviation should be treated as an individual’s personal responsibility and not the responsibility of society. The political spectrum on military issues is described by two opposite positions on the use of military—(1) international conflicts should be resolved through peaceful means and (2) international conflicts should be resolved through military force. The latter side of each issue indicates a traditional or conservative position (associated with a masculine image) on the ideological dimension. Indeed, some evidence suggests that systematic and consistent differences exist in Japan between male and female candidates in their attitudes on these issues; and the differences remain significant even when controlling for partisanship, personal attributes, and district-level characteristics (Ono Reference Ono2015).

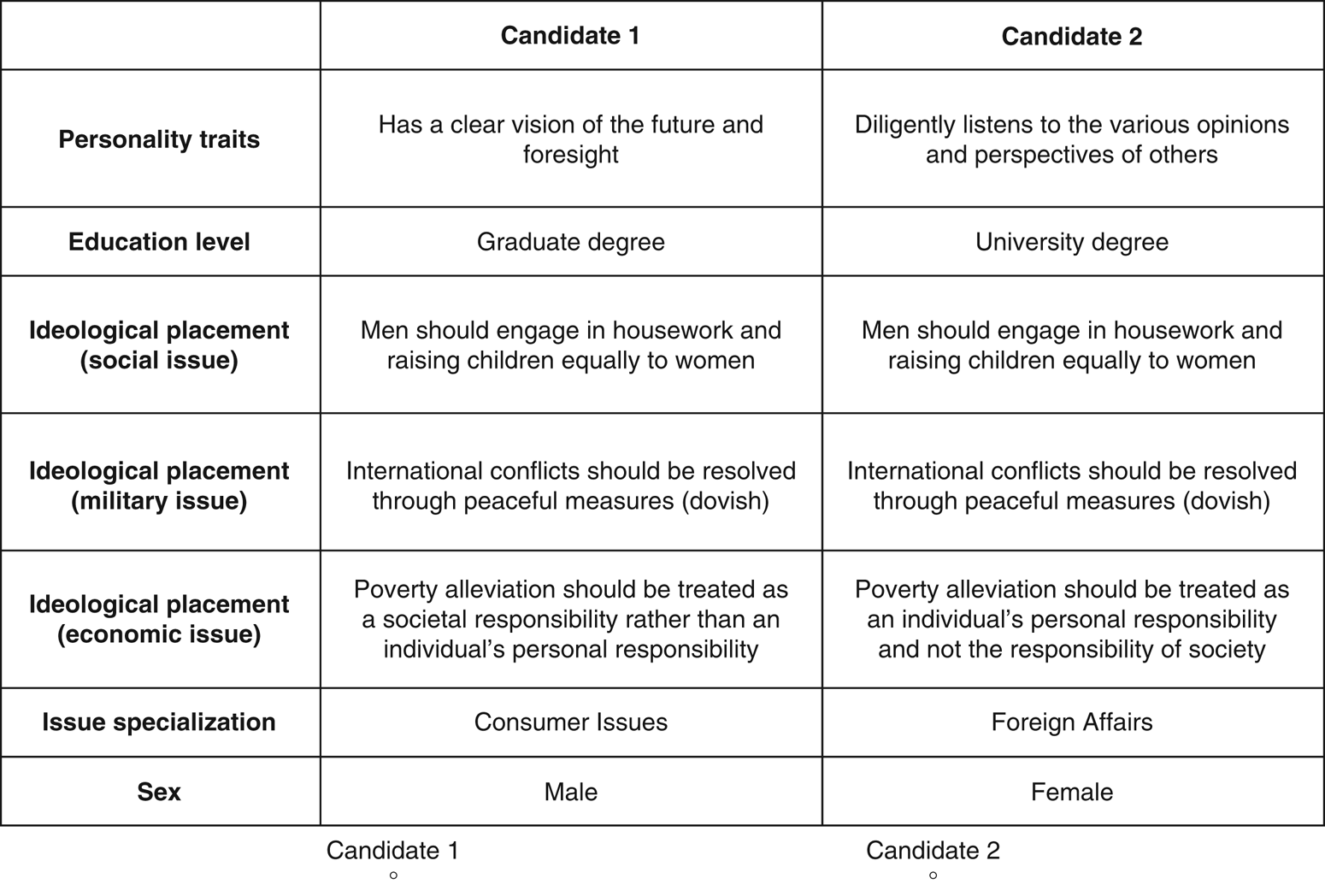

Figure 1 presents one pair of candidate profiles that was shown to a respondent in our experiment (the original design written in Japanese is presented in the Appendix). This research design yields 1152 possible combinations of candidate profiles.Footnote 10 This evaluation task is repeated four times (each pair is displayed on a new screen) so that we are able to obtain a large number of observations to test our hypotheses. The categories of candidate attributes are presented in randomized order across respondents, but the order is fixed across the four pairings for each respondent to minimize his or her cognitive burden. Because so many attributes are varied at a time, it is highly unlikely for our respondents to observe the same combination of attributes in a series of candidate profiles more than once.

Figure 1 Experimental design. Note: This figure shows an example of one set of candidate profiles that was presented to a respondent in our conjoint experiment. The content has been translated from Japanese to English for the reader’s convenience. The original written in Japanese can be found in the Appendix.

Data and Results

We conducted our survey experiment in November 2015. The survey was carried out online with the sample of Japanese adults in the center of the second largest metropolitan area of Japan (Osaka Prefecture), where we could draw samples from people with diverse backgrounds and political views.Footnote 11 The sample was drawn by one of the major survey research companies in Japan – Rakuten Research Inc. In collecting the data, we randomly selected our samples from this survey company’s subject pool after adjusting their demographics to be matched with the population census on age and sex.Footnote 12 A total of 3022 people were invited to our survey, and 2686 people among them completed our conjoint experiment tasks (a completion rate of 88.9 percent). A detailed description of the demographics of the sample is provided in the Appendix. Because each of our respondents evaluated four pairs of candidates, our data have 21,488 evaluated profiles, or 10,744 pairings.

The outcome variables of interest are the choices made by our survey respondents. We coded their responses to our candidate preference question as a binary variable, where a value of one indicates that a respondent supported the candidate and zero otherwise. We also collected personal information from our respondents, including their sex, age, education, annual household income, and partisanship.Footnote 13 The collected data were analyzed following the statistical approach developed in Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto (Reference Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto2014) to estimate the average marginal component effect (AMCE) of each attribute on the probability that the candidate will be chosen, where the average is taken over all possible combinations of the other candidate attributes.Footnote 14

Effects of candidate attributes on electoral support

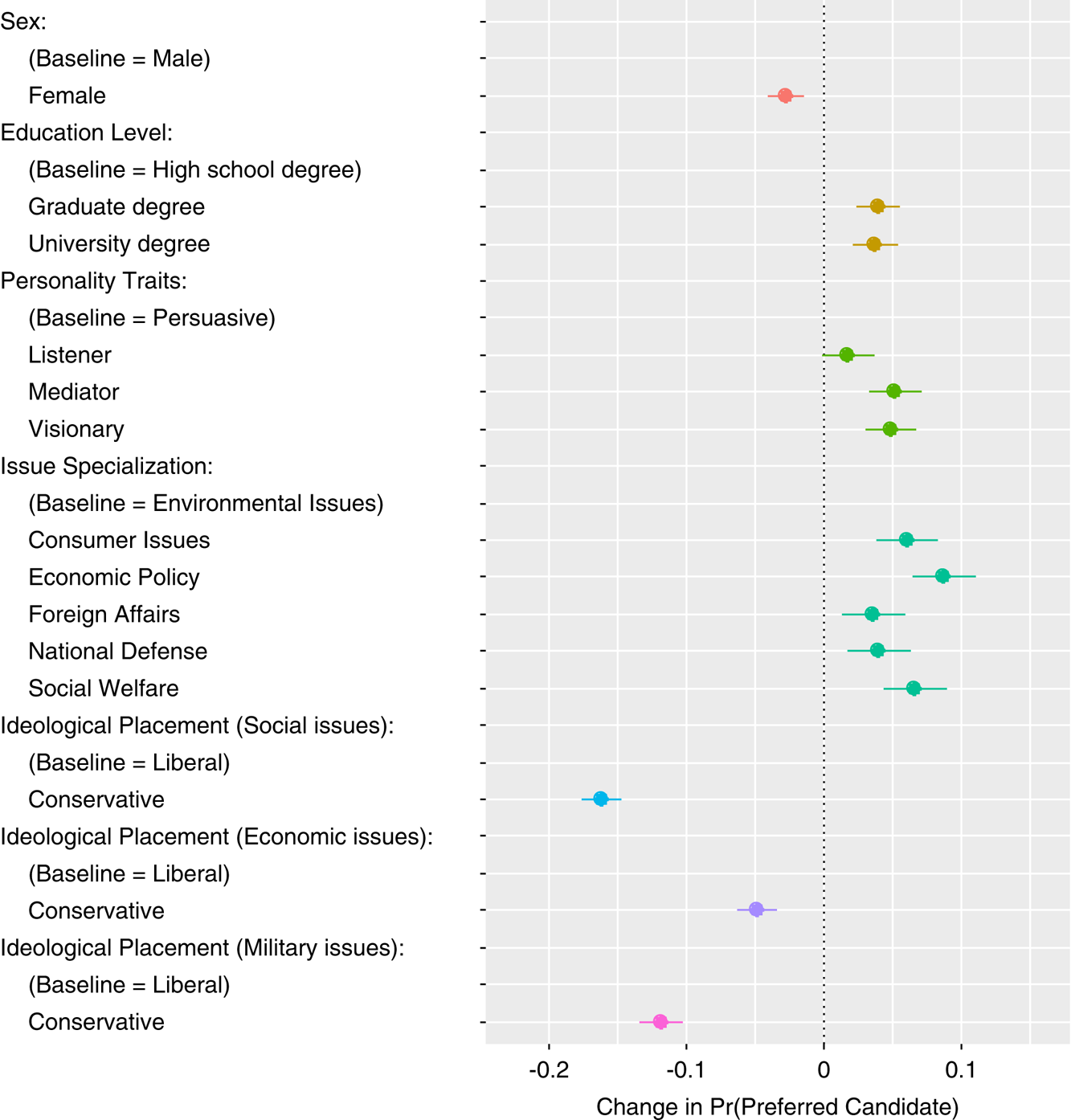

Before presenting the effects of deviations from gender-based expectations on vote choice, we show the relative importance of candidate attributes on electoral support to ascertain whether respondents exhibit any bias against female candidates. Figure 2 presents the results for all respondents. The dots denote point estimates for the AMCE of each attribute value, and the horizontal bars indicate 95 percent confidence intervals. The figure illustrates which attributes of candidates are more (or less) influential when respondents evaluate candidates.

Figure 2 Effects of candidate attributes on voting decisions. Note: Plots show the estimated average effects of the randomly assigned candidate attributes on the probability of being supported by voters. Bars represent 95 percent confidence intervals.

The results of our conjoint experiment demonstrate that a candidate’s personality traits, issue competence, and ideological positions have greater effects on voter decisions than do candidate sex. Among those three factors, the ideological positions have the greatest effect. Candidates with conservative views on social, economic, and military issues are significantly penalized by respondents, compared to candidates with liberal views (their effects are −16.2, −4.8, −11.9 percentage points, respectively). However, such a great negative bias toward conservative views among our respondents is not necessarily a surprising finding, because we purposefully employed extreme conservative positions in our experiment to investigate the effect on voter evaluation when candidates deviate from their gender-based ideological position, which is our main interest in this study. In terms of issue competence, our results show that candidates who specialize in environmental issues have the least electoral advantage compared to those with expertise in other policy areas presented in our experiment. Importantly, however, other “traditional women’s issues” such as social welfare and consumer affairs are almost as equally valued as “traditional men’s issues” such as economic policy, foreign affairs, and national defense. The results also show that respondents value candidates with visionary and mediator traits greater than those with other personality traits, such as persuasive and listener traits. Thus, our respondents do not necessarily value feminine attributes themselves unequally with masculine attributes when evaluating candidates beyond sex.

Our main concern here is the relative importance of a candidate’s sex on voter decisions. The results in Figure 2 show that, while candidate sex does not appear to have much influence on the consideration of respondents in comparison with other candidate attributes, female candidates are clearly disadvantaged compared to the identical male candidates. That is, holding all else constant, our respondents are less likely to vote for female candidates than for male candidates. Compared to male candidates, female candidates have a lower probability of winning support from respondents by 2.7 percentage points (SE=0.69) simply because they are women. This effect of candidate sex appears minimal, but is not negligible in electoral competition, where candidates often win or lose by a narrow margin. Moreover, the bias against female candidates shown in Figure 2 may have been under-estimated, because some randomly generated pairs of candidates have the same sex attribute between them (e.g., some electoral competitions evaluated in our experiment are assumed to be held between two male candidates or two female candidates). Among 12,244 evaluated candidate pairings in our data, 5303 pairings (43.3 percent) have such a same-sex attribute. When we exclude those same-sex pairings and focus only on competitions between different-sex candidates, we find that the bias against female candidates becomes greater than the average one including all the candidate pairings and that respondents are 5.47 percentage points (SE=1.35) less likely to choose a female candidate (this outcome is shown more closely in the Appendix).

To figure out who exhibits a greater bias against female candidates among voters, we further examine the interactions between candidates’ attributes and respondents’ characteristics, such as sex, age, education, income level, and partisanship. Figure 3 compares the estimated

Figure 3 Effects of candidate sex on voting decisions by respondent attributes Note: Plots show the estimated average effects of the randomly assigned candidate sex (female) on the probability of being supported by respondents. Bars represent 95 percent confidence intervals.

marginal effects of candidate sex on voter decision for these subgroups of respondents. The results show that the negative bias against female candidates is greater among male respondents (−3.87, SE=0.98) than female respondents (−1.75, SE=0.98). This finding appears consistent with the existing studies which suggest that women vote for women more than men do (Rosenthal Reference Rosenthal1995; Plutzer and Zipp Reference Plutzer and Zipp1996; Dolan Reference Dolan1997; Seltzer, Newman and Leighton Reference Seltzer, Newman and Leighton1997; Dolan Reference Dolan1998). Yet, the coefficient estimate is not positive for female respondents, suggesting that women are not more likely to vote for female candidates than for male candidates. In other words, voters do not necessarily support candidates who are similar to themselves in terms of sex. Figure 3 further shows that, while middle-aged (30–49 years old) respondents do not exhibit any bias against female candidates, both young (20–29 years old) and elderly (above 50 years old) respondents tend to punish female candidates. The effects of candidate sex also vary across respondents by their household income and partisanship. However, the education levels of respondents do not make any difference in the extent to which they have a negative bias against female candidates.

Effects of deviations from gender-based expectations on electoral support

In the above section, we illustrated the relative importance of candidate attributes on electoral support, showing that respondents exhibit a negative bias against female candidates. What if female candidates downplay their feminine traits? Do voters still punish them at the polls? Respondents might evaluate candidate attributes differently depending on candidate sex; and the same attributes could have different effects between male and female candidates. In order to examine the effects of a candidate’s deviations from his or her gender-based expectations on electoral support, we next analyze the results of interactions between a candidate’s sex and other attributes.

Figure 4 presents the plots of average component interaction effect (ACIE) estimators (with 95 percent confidence intervals) when the candidate is female. The ACIE estimates here represent the percentage point differences in the AMCEs of attributes between a male candidate and a female candidate. Each value indicates the extent to which our respondents reward or punish female candidates with a certain attribute. In the Appendix, we show the ACIE estimates for male candidates, which are all symmetric (or identical mirror images) to those estimates for female candidates shown in this figure.

Figure 4 Effects of candidate attributes on voting decisions conditional on candidate sex Note: Plots show the difference between male and female candidates in their estimated average effects of the randomly assigned candidate attributes on the probability of being supported by voters. Bars represent 95 percent confidence intervals. ACIE= average component interaction effect.

Our results demonstrate that female candidates are neither rewarded nor punished for deviating from gender-based expectations in terms of personality traits and ideological positions. Regardless of whether female candidates show masculine personality traits or take conservative positions on policy issues, our respondents evaluate them as equal to male candidates holding identical personality traits and ideological positions. Interestingly, however, female candidates are rewarded when they show interest and expertise in policy areas that are congruent with a feminine image. Conversely, they are punished when they fail to do so. For instance, environmental concerns have been seen in Japan and elsewhere as being more of a female issue domain (Alexander and Andersen Reference Alexander and Andersen1993; Aiuchi Reference Aiuchi2007). Our results show that, for female candidates, specializing in foreign affairs or economic policy is less advantageous than focusing on environmental issues in gaining electoral support; and that they actually reduce votes by 4.84 and 6.22 percentage points, respectively. In other words, female candidates who specialize in foreign affairs or economic policies do not perform well at the polls, compared to those who emphasize competence in environmental issues. The opposite is true for male candidates. Having feminine traits on issue specialization could negatively affect their vote prospects; and those who show competence in “traditional male issues” (foreign affairs and economic policy) perform better at the polls than those who demonstrate competence in “traditional female issues” (environmental issues).

These results appear to suggest, consistent with the findings by Iyengar et al. (Reference Iyengar, Valentino, Ansolabehere and Simon1996), that female candidates (and male candidates) should play on their “own turf” in their electoral campaigns rather than downplaying their “feminine” traits (or “masculine” traits) in terms of policy specialization. That said, we need to be cautious in interpreting the results shown in Figure 4, because other outcomes are contradictory to our hypotheses. First, although national security is considered as men’s territory, we find no statistically significant difference between being national security experts and environmental issue experts. That is, female candidates who prioritize national security may not fare less well at the polls than those who emphasize environmental issues. Second, we also find that respondents do not necessarily punish female candidates whose policy expertise deviates from other women’s issues, such as social welfare and consumer issues. For female candidates, specializing in foreign affairs or economic policy is equally rewarded as focusing on social welfare and consumer issues in electoral competition. In summary, a female candidate’s policy expertise changes how respondents evaluate the candidate, but only in some limited cases. While female candidates get punished by voters when their issue expertise deviates from environmental issues to foreign affairs or economic policies, they do not necessarily get punished when their expertise deviates from either consumer issues or welfare policies towards foreign affairs or economic policies.Footnote 15

Conclusion and discussion

The number of female representatives is gradually increasing in Japan, but there remains a significant disparity in the share of seats in the Diet between men and women. The striking under-representation of women in politics has been partly attributed to gender stereotypes and prejudice toward female leadership among voters. Since the requirements and qualities of effective leadership are often incompatible with the traditional female gender-role expectations prevailing in Japanese society, there is concern that voters, who perceive such incongruences, may evaluate female candidates unfavorably in elections. Furthermore, this, in turn, may impose a serious dilemma in terms of election strategy for office-seeking women. While female candidates can avoid general biases by embracing more “masculine” traits and policy commitments, they could lose more in doing so by invoking the ire of more traditionally minded voters who shun deviations from gender role expectations. Thus far the literature has not provided a resolution but here we begin to tease out some nuances in the answer to this question.

In order to make precise causal inferences about the effect of gender stereotypes on candidate evaluation among voters, our study employed a conjoint experiment that varied seven attributes of hypothetical candidates, including the ones that have been discussed in the literature on gender stereotypes. Our findings demonstrate that candidate sex has an independent effect on candidate evaluation. Japanese voters overall lean away from female candidates simply because the candidate is a woman. Furthermore, male voters are particularly prone to harbor greater negative biases against female candidates than women voters.Footnote 16 The results of our conjoint experiment also show that deviations from gender-based behavioral expectations never reward female candidates and in some cases even harm their electoral prospects. Although Japanese voters exhibit certain preferences over the personality traits of candidates, they seem to judge female and male candidates equally on these dimensions. Similarly, while Japanese voters tend to associate female candidates with liberal and progressive ideologies, they are tolerant of female candidates who take policy positions that are inconsistent with these ideologies. However, such a tolerance for deviation from gender-based expectations does not extend to the area of issue specialization. Female candidates sometimes perform better when they emphasize their interest and expertise on women’s issues than they do from ignoring such issues. In other words, gender-based behavioral expectations among voters bias their assessment of candidates only in some limited areas, yet it is always better for female candidates not to break with gender stereotypes in maximizing their vote share.

This study has some limitations that are common to experimental settings. For instance, our findings of voters’ behavior are limited to what our respondents do in the experiment, and actual voting behavior could deviate in some ways from that found in the experimental environment. The concerns of a social desirability bias have been minimized in our conjoint experiment by providing respondents with multiple reasons to justify their choices. Yet there still exists a possibility that the gender bias found in our experiment may have been overstated (or understated) due to the lack of verisimilitude. While realism has been enhanced to some extent in our conjoint experiment by presenting respondents with multiple pieces of information at a time, our experiment does not comprehensively cover all the pieces of information and political conditions that might influence voters’ candidate evaluation. Candidates who take counter-stereotypical positions may be more frequently covered by mass media and journalist than those who take stereotypical positions.Footnote 17 The campaign context may also affect how voters evaluate female candidates who deviated from their gender-based expectations (see Krupnikov and Bauer Reference Krupnikov and Bauer2014). More research needs to be conducted to further clarify the nuances and impact of gender bias among voters.

Future research can build upon this work and deepen our understanding of this topic in several ways. First, issues such as education, childcare, crime, and taxes have not been included in our experiment. Because the association between candidate sex and issue specialization varies across policy areas, researchers need to further examine the effects of other issues in order to complete our understanding of how gender-linked issue specialization exerts influence on candidate evaluation. Second, partisan cues have been excluded from our candidate profiles so as to control for the effect of candidate partisanship. This is especially important when considering gender stereotypes in the context of Japanese politics, where candidates of numerous parties compete in elections. Since policy positions of candidates are closely correlated with their party affiliation under multiparty systems like the one in Japan, many candidate profiles become highly implausible when we include a partisan cue. However, withholding a partisanship cue may have inflated the effect of candidate sex in our results (see Kirkland and Coppock Reference Kirkland and Coppock2018). It would be useful to further examine how the information of candidate partisanship interacts with voters’ gender-based candidate assessments. Third, and finally, assuming the electoral competition for the national-level office may have inflated the negative effect of candidate sex in our results. The gender-office congruency theory suggests that female candidates are likely to face a greater challenge as they run for a higher level of office due to gendered leadership stereotypes (Huddy and Terkildsen Reference Huddy and Terkildsen1993a; Huddy and Terkildsen Reference Huddy and Terkildsen1993b; Rose Reference Rose2013; Lawrence and Rose Reference Lawrence and Rose2014). Further research is needed to understand how gender bias might be shifted by the level of office which candidates are seeking.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2018.41

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank the editor and reviewers, Barry C. Burden, Yusaku Horiuchi, Jonson Porteux, Justin Reeves, Daniel M. Smith, and participants of the Contemporary Japanese Politics Study Group at Harvard University, the Center for Political Studies Interdisciplinary Workshop at the University of Michigan, the Terasaki Center for Japanese Studies Colloquium at UCLA, Chicago Area Political and Social Behavior Workshop at Northwestern University, and Discussion Paper Seminar at the Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry (RIETI) for their helpful comments on earlier drafts. The authors also appreciate the assistance of Masahiro Zenkyo with the data collection process. This research was financially supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (17K03523; 26285036; 26780078) and the Kwansei Gakuin University Research Grant. Y.O. also received the JSPS Postdoctoral Fellowship for Research Abroad.