“Our openness is part of who we are…we must never give in to those who would throw away our values, with the appalling prospect of repatriating migrants who are here totally legally and have lived here for years. We are Great Britain because of immigration, not in spite of it.” (David Cameron, UK Prime Minister, 28 November 2014)Footnote 1

“For more than 200 years, our tradition of welcoming immigrants from around the world has given us a tremendous advantage over other nations. It's kept us youthful, dynamic, and entrepreneurial.” (Barack Obama, US President, 20 November 2014)Footnote 2

“My story is really not much different from millions of other Americans. Immigrants have been coming to our shores for generations to live the dream that is America. They wanted better for their children than for themselves. That remains the dream of all of us, and in this country we have seen time and again that that dream is achievable.” (Nikki Haley, Governor of South Carolina, 12 January 2016)Footnote 3

Politicians devote significant attention to the issue of immigration. Some demonize immigrants and use this issue to enflame xenophobia, often reaping electoral rewards in the process (Brader et al., Reference Brader, Valentino and Suhay2008; Ivarsflaten, Reference Ivarsflaten2008; Ford et al., Reference Ford, Goodwin and Cutts2012). However, politicians also regularly champion immigration, as the opening quotations illustrate. Whether these pro-immigration appeals raise tolerance of immigrants remains unexplored.

The frequency with which politicians endorse immigration makes the lack of scholarly attention to these appeals a striking omission. Between 1998 and 2013, party manifestos in Western Europe and North America spoke positively about immigration more often than negatively (Lehmann and Zobel, Reference Lehmann and Zobel2018). Although the success of the radical right has made some mainstream parties skeptical toward immigration (Abou-Chadi and Krause, Reference Abou-Chadi and Krause2020), most have not radicalized their stance (Alonso and Fonseca, Reference Alonso and d. Fonseca2012; Mudde, Reference Mudde2013; Akkerman, Reference Akkerman2015). In the USA, Democrats firmly support immigration (Wong, Reference Wong2017), and Republicans, despite their party's general hardline stance on this issue, have described the country as “…a melting pot with room for those who dare to dream,”Footnote 4 stressed that “…people from everywhere have made America great,”Footnote 5 and said that “America's immigrant history made of us who we are.”Footnote 6

Building on Zaller's (Reference Zaller1992) groundbreaking research on the influence of elite discourse in shaping public opinion, we systematically study whether and how pro-immigrant political speech increases tolerance toward immigrants in native populations.Footnote 7 We explore three types of positive speech about non-natives commonly used by politicians: (1) stressing common humanity, (2) reinforcing norms of inclusivity and acceptance of diversity, and (3) countering negative stereotypes. Tolerance toward out-groups is based on in- and out-group conceptions (Allport, Reference Allport1954; Tajfel and Turner, Reference Tajfel, Turner, Austin and Worchel1979; Citrin et al., Reference Citrin, Reingold and Green1990), and we argue that these types of speech have the potential to shift natives’ perceptions of immigrants as an out-group. More specifically, we posit that stressing common humanity promotes tolerance because it invokes empathy and extends conceptions of in-group membership to former out-group members (Broockman and Kalla, Reference Broockman and Kalla2016; Robinson, Reference Robinson2016; Simonovits et al., Reference Simonovits, Kezdi and Kardos2018). Reinforcing inclusivity and acceptance of diversity as in-group norms increases tolerance by framing tolerant attitudes and behavior as characteristics of in-group members (see Paluck and Green, Reference Paluck and Green2009; Blinder et al., Reference Blinder, Ford and Ivarsflaten2013; Tankard and Paluck, Reference Tankard and Paluck2016). Countering negative stereotypes fosters tolerance by providing accurate information about out-groups and thereby undermining perceptions of out-group threat, which are often based on invalid negative information about those groups (Tversky and Kahneman, Reference Tversky and Kahneman1973; Blinder, Reference Blinder2015).

Our empirical design relies on real political speech by national leaders and we conducted two separate experimental studies: a main study that was embedded over three waves of a national survey ($N\approx 3000$![]() ), and a replication on Amazon's Mechanical Turk (MTurk, $N\approx 2000$

), and a replication on Amazon's Mechanical Turk (MTurk, $N\approx 2000$![]() ). The experiments randomly assigned respondents to one of the three political speech treatments (i.e., stressing common humanity, reinforcing norms of tolerance, or countering stereotypes) or a control condition before measuring attitudes and behavior toward immigrants. We find that the norms and countering stereotypes treatments manipulated in- and out-group perceptions as intended, and increased tolerant attitudes (but not behavior), although these effects were small and detectable only in sufficiently large samples. The common humanity treatment consistently failed to alter in- and out-group perceptions, attitudes and behavior. To summarize, the pro-immigrant political speech in our experiments had some, albeit limited, power to increase attitudinal tolerance toward immigrants. This result is important because it clarifies the scope for politicians to shift attitudes against the background of a broad literature that explores the persistence and stability of inter-group attitudes (Allport, Reference Allport1954; Katz, Reference Katz1976; Kinder and Sears, Reference Kinder and Sears1981; Henry and Sears, Reference Henry and Sears2009) and anti-immigrant predispositions (Fielding, Reference Fielding2018).

). The experiments randomly assigned respondents to one of the three political speech treatments (i.e., stressing common humanity, reinforcing norms of tolerance, or countering stereotypes) or a control condition before measuring attitudes and behavior toward immigrants. We find that the norms and countering stereotypes treatments manipulated in- and out-group perceptions as intended, and increased tolerant attitudes (but not behavior), although these effects were small and detectable only in sufficiently large samples. The common humanity treatment consistently failed to alter in- and out-group perceptions, attitudes and behavior. To summarize, the pro-immigrant political speech in our experiments had some, albeit limited, power to increase attitudinal tolerance toward immigrants. This result is important because it clarifies the scope for politicians to shift attitudes against the background of a broad literature that explores the persistence and stability of inter-group attitudes (Allport, Reference Allport1954; Katz, Reference Katz1976; Kinder and Sears, Reference Kinder and Sears1981; Henry and Sears, Reference Henry and Sears2009) and anti-immigrant predispositions (Fielding, Reference Fielding2018).

Our study has three distinct strengths that contribute to a better understanding of what does and does not work in enhancing tolerance toward immigrants. We offer the first investigation of the effects of real political speech on expanding attitudinal and behavioral tolerance toward immigrants. This improves on prior research that has either looked at the positive framing of the immigration issue in other contexts (Haynes et al., Reference Haynes, Merolla and Ramakrishnan2016; Voss et al., Reference Voss, Silva and Bloemraad2019) or used artificial political speech (Flores, Reference Flores2018). Our focus on real political speech has particular practical importance because politicians’ messages are amplified by the media in a way that other messages are not (see, e.g., Azari, Reference Azari2016). Second, our study directly evaluates three clearly specified and theoretically derived mechanisms, while prior research often uses complex treatments that do not clearly isolate the mechanism (see, e.g., Simonovits et al., Reference Simonovits, Kezdi and Kardos2018). Third, we consider both attitudes and behavior, thereby establishing the scope of the political speech effects. We elaborate on our contributions in the conclusion.

1. Political speech and fostering tolerance of immigrants: theory

Tolerance of immigrants and foreigners—a “friendly and trustful attitude that one person may have toward another, regardless of the groups to which either belongs” in Allport's (Reference Allport1954, p. 425) formulation—is based on generalized beliefs and opinions about them as a group (Harding et al., Reference Harding, Proshansky, Kutner, Chein and Lindzey1954). Reduced tolerance, resulting from negative beliefs and opinions of immigrants, shapes policy preferences (see, e.g., Burns and Gimpel, Reference Burns and Gimpel2000; McLaren, Reference McLaren2003; Ivarsflaten, Reference Ivarsflaten2005), fuels anti-immigrant violence, inspires protests, and swells the ranks of nativist political movements (Ivarsflaten, Reference Ivarsflaten2008; Merolla et al., Reference Merolla, Pantoja, Cargile and Mora2013; Benček and Strasheim, Reference Benček and Strasheim2016). Moreover, elites condition mass opinion (Zaller, Reference Zaller1992). Elite discussions of immigration influence tolerance: negative and threatening frames of the issue raise the prevalence of exclusionary attitudes toward immigrants (Hopkins, Reference Hopkins2010; Albertson and Gadarian, Reference Albertson, Gadarian, Freeman, Hansen and Leal2013; Haynes et al., Reference Haynes, Merolla and Ramakrishnan2016), enhance opposition to immigration (Brader et al., Reference Brader, Valentino and Suhay2008; Blinder, Reference Blinder2015), and amplify the influence of ethnic identity in politics (Pérez, Reference Pérez2015). However, little is known about the effects of pro-immigrant political speech on tolerance of this group.

We argue that pro-immigrant political speech can foster tolerance by altering perceptions of in- and out-groups. Our argument proceeds in two steps. First, we build on insights from social identity theory (SIT; Tajfel and Turner, Reference Tajfel, Turner, Austin and Worchel1979) to identify the mechanisms that account for the reduced tolerance of out-groups. We then discuss how counteracting each of the mechanisms can increase tolerance.

According to SIT, beliefs and opinions about groups derive from conceptions of group identities (Citrin et al., Reference Citrin, Reingold and Green1990; Kalkan et al., Reference Kalkan, Layman and Uslaner2009; Wright, Reference Wright2011). Three inter-connected processes are relevant. First, individuals self-categorize as members of a specific social group, leading to identification with that group and giving rise to a social identity (Tajfel and Turner, Reference Tajfel, Turner, Austin and Worchel1979). Simultaneously, an individual categorizes others as either sharing their identity (members of the in-group), or as being different (members of the out-group). Second, individuals’ psychological needs to maintain in-group membership require adherence to in-group norms that describe and prescribe the attitudes and behavior of group members (Hogg and Reid, Reference Hogg and Reid2006). Third, due to a need for positive self-esteem, individuals extend positive regard, cooperation, and empathy to in-group members, but negatively evaluate the out-group (Tajfel and Turner, Reference Tajfel, Turner, Austin and Worchel1979; Turner and Reynolds, Reference Turner, Reynolds, Van Lange, Kruglanski and Higgins2012). As a result, out-group members are perceived as threatening the positive distinctiveness of the in-group (Quillian, Reference Quillian1995; Hewstone et al., Reference Hewstone, Rubin and Willis2002; Dancygier, Reference Dancygier2010). Together, these three mechanisms—categorization, maintaining membership of a favored in-group, and out-group threat perceptions—reduce the tolerance that in-group members exhibit in their attitudes and actions toward out-group members (see, e.g., Tajfel and Turner, Reference Tajfel, Turner, Austin and Worchel1979).

We argue that interrupting each of these three mechanisms can increase tolerance. We discuss possible interventions corresponding to each mechanism in turn and apply them to political speech.

1.1 Common humanity: expanding the in-group

Interventions that extend conceptions of in-group membership to former out-group members can be effective at fostering tolerance. Such interventions invoke empathy by drawing on shared experiences of in- and out-group members (perspective taking) or by directly appealing to a shared superordinate identity (common humanity). As Gaertner and Dovidio (Reference Gaertner and Dovidio2005, p. 625) note, “if members of different groups are induced to conceive of themselves as a single group rather than as two completely separate groups, attitudes toward former out-group members will become more positive through the cognitive and motivational forces that result from in-group formation.”

Evidence from a wide range of contexts indicates the effectiveness of in-group expanding interventions (see, e.g., Broockman and Kalla, Reference Broockman and Kalla2016; Robinson, Reference Robinson2016; Simonovits et al., Reference Simonovits, Kezdi and Kardos2018). Specifically in relation to non-natives, Lazarev and Sharma (Reference Lazarev and Sharma2017) study relations between Turks and Syrian refugees and find that appealing to a shared religious Muslim or Sunni identity reduces exclusionary behavior and attitudes (see also Haynes et al., Reference Haynes, Merolla and Ramakrishnan2016). Applying the common humanity intervention to pro-immigrant political speech, we anticipate that:

Hypothesis 1 (Common Humanity): Political speech that extends conceptions of in-group membership to immigrants increases tolerance.

1.2 Norms: introducing inclusiveness and acceptance of diversity as in-group norms

Interventions that promote acceptance of diversity and inclusiveness as normative for the in-group can also impact tolerance toward out-groups. These interventions build on individuals’ psychological need to maintain group membership (e.g., Tajfel and Turner, Reference Tajfel, Turner, Austin and Worchel1979), which requires following in-group norms that delineate the attitudes, behaviors, and traits of the in-group from those of out-groups (Hogg and Reid, Reference Hogg and Reid2006). Interventions that emphasize in-group norms of inclusiveness and acceptance may therefore cause individuals to adjust their attitudes and behaviors to match these norms.

Empirical research indicates that efforts that target perceptions of social norms are highly effective (see, e.g., Stangor et al., Reference Stangor, Sechrist and Jost2001; Paluck and Green, Reference Paluck and Green2009). Regarding immigrants in particular, Blinder et al. (Reference Blinder, Ford and Ivarsflaten2013) show that highlighting anti-prejudice in-group norms increases support for the equal treatment of asylum seekers. In the context of political speech, this discussion leads to the following expectation:

Hypothesis 2 (Norms): Political speech that introduces inclusiveness and acceptance of diversity as normative for the native in-group increases tolerance.

1.3 Countering stereotypes: providing accurate information about immigrants

Interventions that target negative stereotypes, i.e., invalid generalized associations between immigrants and a series of social and economic problems, by providing accurate information about the out-group, can reduce threat perceptions and increase tolerance. Perceptions of immigrants often significantly diverge from reality in ways that exacerbate perceptions of threat (Blinder, Reference Blinder2015). For example, members of the public tend to overestimate the number of immigrants in the population and this innumeracy correlates strongly with threat perceptions from immigrants and with restrictive immigration policy preferences (Citrin and Sides, Reference Citrin and Sides2008; Herda, Reference Herda2015).

Information that corrects misperceptions and counters stereotypes can change attitudes and preferences. For example, a recent study shows that, out of 17 interventions tested, providing counter-stereotypical information about racial groups (e.g., linking blacks with positivity) was most effective at reducing implicit racial bias (Lai et al., Reference Lai, Marini, Lehr, Cerruti, Shin, Joy-Gaba, Ho, Teachman, Wojcik, Koleva, Frazier, Heiphetz, Chen, Turner, Haidt, Kesebir, Hawkins, Schaefer, Rubichi, Sartori, Dial, Sriram, Banaji and Nosek2014; see also Finnegan et al., Reference Finnegan, Oakhill and Garnham2015). In the immigration context, Facchini et al. (Reference Facchini, Margalit and Nakata2016) performed a large-scale experimental study in Japan and found that information regarding the potential social and economic benefits from immigration increased support for a more open immigration policy. Information that focuses on the sociotropic benefits of immigration appears critical: just providing correct information about the scope of immigration has no effect on attitudes (Hopkins and Citrin, Reference Hopkins, Sides and Citrin2019). In the context of political speech, this implies:

Hypothesis 3 (Countering Stereotypes): Political speech that provides information about the sociotropic benefits of immigration increases tolerance.

2. Research design

We test our hypotheses with two survey experiments (a Main Study and a Replication), which randomly assigned respondents to read one of four short texts: three composed of actual statements from US politicians on immigration and one non-political control text. The survey experiments have two important advantages compared to observational studies of the effects of pro-immigration political speech. First, randomization allows us to rule out confounding and reverse causality between tolerance toward immigrants and exposure to pro-immigrant political speech. Second, we can tailor treatments that use real political speech but emphasize one of the three mechanisms described above.

We fielded our Main Study as part of Qualtrics’ online omnibus survey over three waves: October 2018, November 2018, and December 2018–January 2019. The omnibus survey includes approximately 1000 respondents per wave, with the target population comprising adult US citizens.Footnote 8 Qualtrics uses quotas for gender, age, ethnicity, household income, and US Census regions to produce samples that are approximately nationally representative. We ran our questionnaire in three waves to (a) achieve sufficiently large sample size, and (b) ensure that the data do not represent a single (and potentially unusual) timepoint and that the results have some generalizability over time. The final sample includes close to 3000 respondents. More information on the survey and sample can be found in Supplementary Information (SI) 1. We pre-registered an analysis plan for our survey results (available in SI 2); all results reported below follow that plan unless otherwise indicated. We ran our Replication Study in December 2019 on Amazon MTurk with a sample of roughly 2000 respondents (see SI 3 for more information on the Replication).Footnote 9

2.1 Treatments

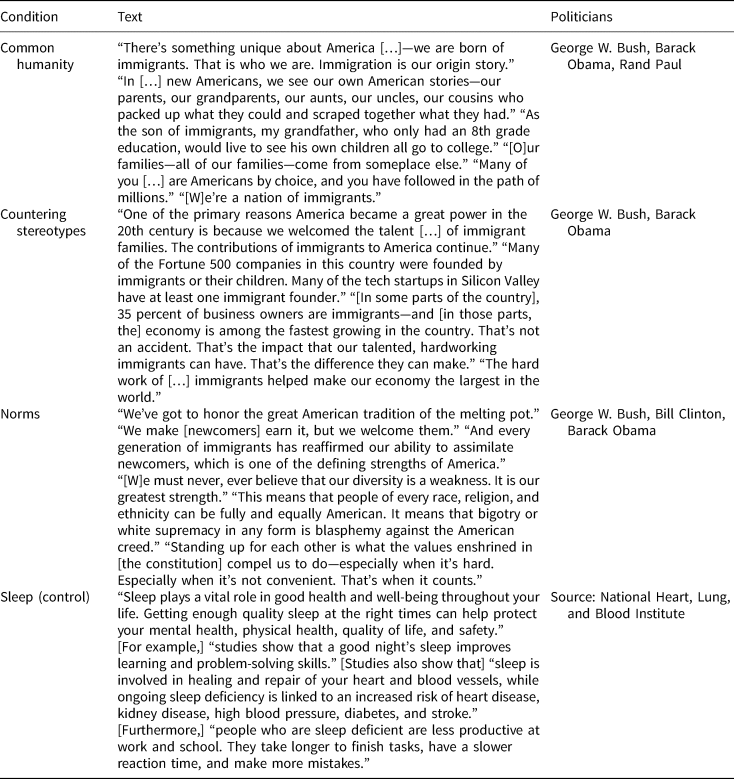

Respondents were randomly assigned to read one of four short texts, which we label Common Humanity, Countering Stereotypes, Norms, and Control. We constructed the treatment texts using statements on immigration from US politicians—both Republicans and Democrats. The control text explained the benefits of sleep. We introduced the treatment texts with the following preamble: “Please carefully read the following excerpts from speeches made by prominent politicians in the U.S. about immigration. Once you have read the text, we will ask you a few questions about them.”Footnote 10 The Common Humanity text focuses on quotes that extend conceptions of in-group membership (e.g., phrases that remind readers that “we are all immigrants”) and tests H1. The Norms text contains quotes that call on Americans to uphold in-group norms of inclusiveness and acceptance of diversity; we use it to test H2. Similarly, we test H3 with the Countering Stereotypes text, which presents information about the positive contribution of immigrants to the American economy. Table 1 presents each of the four texts in full.

Table 1. Treatment information

We subjected our treatments to pre-tests, which asked respondents to what extent they thought each vignette represented its intended theme. Pre-tests used samples of university undergraduates or MTurkers. Results of the final pre-test, which used an MTurk sample and tested vignettes that closely match those used in the main study and pilots, are available in SI 7 (see also Table S.17) and confirm that our treatments largely work as intended. That is, among the three texts, the one on Common Humanity was the most effective at conveying the message that immigrants and Americans share a common humanity. Similarly, the messages that American norms include tolerance toward immigrants and that immigrants are good for the economy were best communicated by the Norms and Countering Stereotypes texts, respectively.

Our treatment design aims to maximize realism, retain respondent attention and minimize confounding by factors other than the themes contained in the quotes. To maximize realism we construct our treatments from actual pro-immigrant speech by politicians. We also calibrated the length of our quotes to represent a reasonable amount of exposure to political speech: our quotes are longer than newspaper headlines but shorter than full-length articles. Pre-test respondents spent roughly 80 seconds reading the treatments, which resembles the average amount of time that an individual stays engaged with a news article.Footnote 11 As prior research has found significant treatment effects of one- to three-sentence xenophobic messages (e.g., Pérez, Reference Pérez2015), we believe that our treatments are long enough that respondents can absorb the intended messages yet short enough that respondents do not lose attention. Furthermore, restricting the treatment to text, rather than audio or video, eliminates the possibility that a speaker's style and persuasiveness influence responses to treatment.

We did not inform respondents of who delivered the statements on immigration. This approach follows other research on xenophobia (Pérez, Reference Pérez2015) and provides a clean test of the effects of the message content, independent of any extraneous factors such as the identity of the messenger. It is important to first establish the baseline effect of pro-immigrant messages as we do here. Only then can one start exploring possible messenger effects, which are likely to vary across time and political contexts with party attachment and partisan conflict (Slothuus and De Vreese, Reference Slothuus and De Vreese2010). Pre-test results reported in SI 7 show that 72 percent of respondents attributed the quotes to Democrats, 8 percent to Republicans, and 19 percent to politicians from both parties. To the extent that pro-immigrant messages from Democrats have smaller effects, given Democrats’ general support for immigration, these perceptions work against finding an effect for our treatments, which contain roughly equal numbers of statements from both parties.Footnote 12 In SI 4, we therefore also examine whether the effects of our message themes differ by respondent partisanship and find no systematic differences between Democrats and Republicans, and weak evidence of a larger effect among independents.

2.2 Attitudinal outcomes

Our survey included two sets of outcomes: attitudinal and behavioral. Attitudinally, we capture tolerance of immigrants with two items. First, we asked if respondents would “…welcome it or object if a couple who has come to live in the US from another country moved in as your neighbors?” Answers to this question use a seven-point scale that ranges from “Welcome a lot” to “Object a lot.” This item, labeled Immigrant Neighbors, relies on prior research (e.g., Ward, Reference Ward2019) and directly measures a key component of tolerance: an openness to the presence of out-group members in a respondent's community (Bobo and Zubrinsky, Reference Bobo and Zubrinsky1996).

Second, we asked respondents whether they think “that the USA should reduce or increase opportunities for people from other countries to come and live here?” Again, we provided seven response categories, ranging from “Should reduce opportunities” to “Should increase opportunities.” This question appears frequently in studies of immigration attitudes and on large-scale surveys such as the European Social Survey. The measure, labeled Increase Immigration, gauges the disposition to welcome immigrants into the country, and thereby again directly captures tolerance.

We combine these two items using scores from the first dimension of a principal component analysis to create Immigration Index.Footnote 13 Combining responses to our items minimizes variance due to random measurement error, affording us greater statistical precision. As this increased precision comes at the cost of interpretability, we present results for the individual items as well. We did not pre-register analyses with Immigration Index.

2.3 Behavioral outcome

If pro-immigrant political speech increases tolerance, we would expect to see this reflected not only in natives’ attitudes, but also in their behavior. Tolerance of out-groups often finds expression in increased trust (see, e.g., Borgonovi, Reference Borgonovi2012; Stolle and Harell, Reference Stolle and Harell2013). To systematically measure how much natives trust immigrants in interactions, we follow previous research by including a behavioral game in our survey (e.g., Habyarimana et al., Reference Habyarimana, Humphreys, Posner and Weinstein2007; Whitt and Wilson, Reference Whitt and Wilson2007).

After reading the treatment vignette, but prior to the attitudinal items, respondents participated in four rounds of a trust game, which we modeled on prior studies (e.g., LeVeck et al., Reference LeVeck, Hughes, Fowler, Hafner-Burton and Victor2014). In each round of the game, respondents were given an endowment of ten tokens and told that their payoff depended on the number of tokens they had at the end of the game. Respondents played the game by passing some, all, or none of their tokens to their partner. We told respondents that we would triple the number of tokens sent to the partner, who would then return some, all, or none of the tokens.

The instructions to the game stated that respondents would play with other survey participants. In reality, the partners were fictitious; we explained this to respondents during debriefing. We provided four pieces of information about partners in each round: the partner's age, state of residence, gender, and whether he or she was born in the USA. We did not randomize age and state of residence; these changed from round to round but were the same for all respondents in a given round. In contrast, we randomized gender and country of birth across rounds and respondents.

If respondents expected their partner to return more than one-third of the tokens, they could increase their final payoff by sending more tokens. Otherwise, they maximized their payoff by keeping all of the tokens. Hence, the greater a respondent's trust in their partner to return more than one-third of the tokens, the higher the expected payoff from sending more tokens. To induce serious play, we informed respondents that one randomly chosen participant would receive a payment of $10 per token in their possession at the end of the game. Prior to the start of the game, we presented respondents with detailed instructions and examples of how to play; SI 1.4 presents this text, which closely follows LeVeck et al. (Reference LeVeck, Hughes, Fowler, Hafner-Burton and Victor2014).

From the trust game, we measure the number of Tokens Given to the second player in each round, which varied from 0 to 10. Because we randomized the partner's national origin (country of birth: USA, other), we can measure whether respondents shared fewer tokens with immigrants than with natives (i.e., reduced out-group trust) and test whether exposure to pro-immigrant political speech increases this trust.

2.4 Empirical methods

We estimate treatment effects with linear regression. For the attitudinal outcomes, the regressions adjust for all the covariates collected as part of our study (Age, Education, Race, Gender, Region, Partisanship, News Consumption, Survey Wave). As higher values indicate greater tolerance of immigrants for all three attitudinal outcomes, we expect the coefficients on our treatments to be positive and significant: consuming the pro-immigration messages contained in the treatment texts should increase tolerant attitudes.

For Tokens Given, we use a difference-in-differences type specification, in which we interact each treatment with partner origin, include respondent fixed effects, round fixed effects, controls for partner gender and origin, and cluster standard errors at the respondent level. We expect the pro-immigrant speech treatments to increase trust and shrink the gap in Tokens Given between native and foreign-born partners compared to the control group. In terms of regression coefficients, we expect positive effects on the interactions between treatment and partner origin. All empirical specifications follow our pre-analysis plan (which includes formal regression equations; see SI 2).

3. Results

We present our results in two steps. First, we explore whether the manipulation worked as intended, i.e., whether respondents understood the treatment vignettes and adjusted their perceptions of the in-group, out-group, and social norms to match the messages conveyed in the treatments. After that, we estimate the effects of our treatments on immigration attitudes and trust game behavior.

3.1 Comprehension of vignette themes and manipulation check

Three conditions must be met for the political speech contained in our treatments to impact attitudes and behavior. First, the speech must convey the intended messages. Our pre-tests confirm that this condition is met (see above, SI 7 and Table S.17). Second, respondents must understand the content of our vignettes. Third, if the treatments impact attitudes according to the mechanisms we propose, respondents’ beliefs about in-group and out-group membership, norms, and immigrants’ economic contributions must shift based on the treatment they received. We test the second and third conditions below in our Main Study (see Table S.5 for the corresponding estimates from the Replication).

We assess treatment comprehension with three yes-or-no questions that required respondents to recall the content and arguments of the text that they read. To prevent respondents from “straight-lining” through these questions, two questions had “yes” as the correct answer, one “no” (for question wording, see SI 1.3). These questions appeared in randomized order immediately after our treatment texts.

Respondent comprehension of treatments was generally high: on average, respondents answered 2.27 (out of 3) questions correctly.Footnote 14 Split by treatment, the average numbers of correct answers in the Common Humanity, Norms, and Countering Stereotypes groups were 2.30, 2.19, and 2.31, respectively. The low variation in correct answer rates across treatments indicates that vignette comprehensibility was similar.

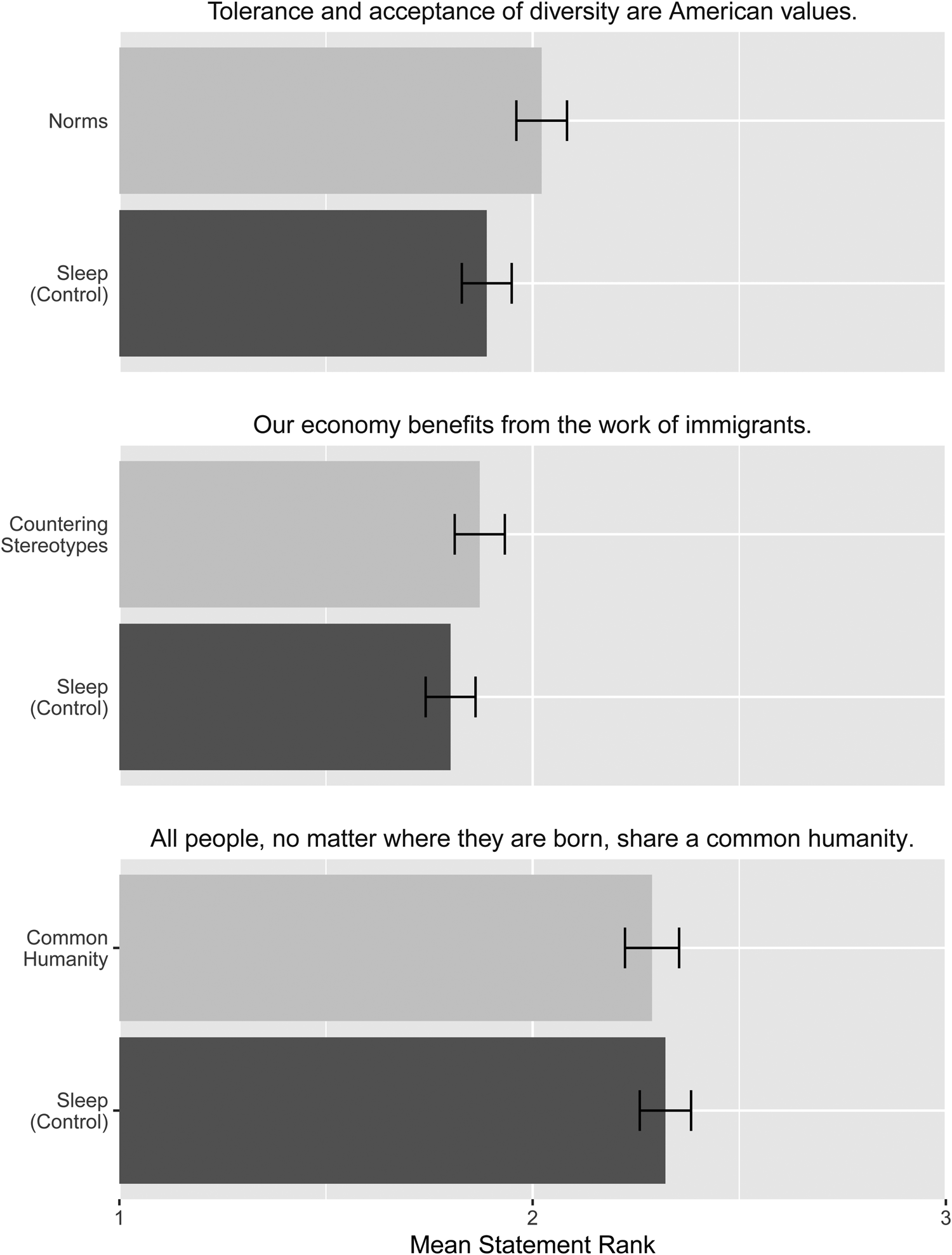

We now assess whether our treatments affected perceptions of in-group membership, in-group norms, and out-group contributions as intended. This serves as a manipulation check. Specifically, we presented respondents with the following three statements (in random order and after treatment): “All people, no matter where they are born, share a common humanity”; “Tolerance and acceptance of diversity are American values”; and “Our economy benefits from the work of people who have come to live here from other countries.” These statements capture the perceptions we intended to manipulate with the Common Humanity, Norms, and Countering Stereotypes treatments, respectively. We then asked respondents to “rank them in the order in which you agree with them, from 1 = you agree with the most to 3 = you agree with the least.” From these rankings, we created the variable Statement Ranking for each statement, reversing the scale so that higher values indicate greater agreement.

Figure 1 reports the average of Statement Ranking for each statement. The top panel presents rankings for the Norms statement, the middle and bottom panels for the Countering Stereotypes and the Common Humanity statements. Each panel contrasts the average for respondents whose treatment matches the statement with the average for the control group. If respondents adjusted their perceptions to match the arguments that they read, then we should find higher values when the treatment and statement match. We formalize these differences with regression estimates that adjust for covariates (see Table S.4). Respondents in the Norms group ranked this statement 0.13 points higher than the control group, on average ($\rm {p}< 0.01$![]() ; all p-values represent two-sided tests), while Countering Stereotypes respondents placed that statement 0.07 points higher than the control group, on average ($\rm {p} < 0.10$

; all p-values represent two-sided tests), while Countering Stereotypes respondents placed that statement 0.07 points higher than the control group, on average ($\rm {p} < 0.10$![]() ). In contrast, respondents who read the Common Humanity treatment had lower levels of agreement with the corresponding statement than control respondents (difference $= -0.02$

). In contrast, respondents who read the Common Humanity treatment had lower levels of agreement with the corresponding statement than control respondents (difference $= -0.02$![]() , $\rm {p} = 0.61$

, $\rm {p} = 0.61$![]() ). Additionally, Figure S.4 compares the treatment groups to each other and shows that each statement is ranked highest by the group that received the corresponding treatment. Again, however, the differences are larger with respect to Norms and Countering Stereotypes than Common Humanity.

). Additionally, Figure S.4 compares the treatment groups to each other and shows that each statement is ranked highest by the group that received the corresponding treatment. Again, however, the differences are larger with respect to Norms and Countering Stereotypes than Common Humanity.

Fig. 1. Manipulation check: respondents’ perceptions based on treatment assignment.

Note: Bars represent within-group averages with 95 percent confidence intervals.

In sum, these tests show that respondents understood our treatments, but that uptake of the intended messages was mixed. Respondents clearly absorbed the Norms message, and to a lesser extent, the Countering Stereotypes message increased agreement with the corresponding theme. The Common Humanity treatment did not increase agreement that “All people, no matter where they are born, share a common humanity.” This null result may reflect a ceiling effect: as Figure 1 shows, control respondents agreed with the common humanity statement at high levels, meaning that respondents in the Common Humanity group may have received a text that tried to persuade them of something they largely already believed.

3.2 Effects on immigration attitudes

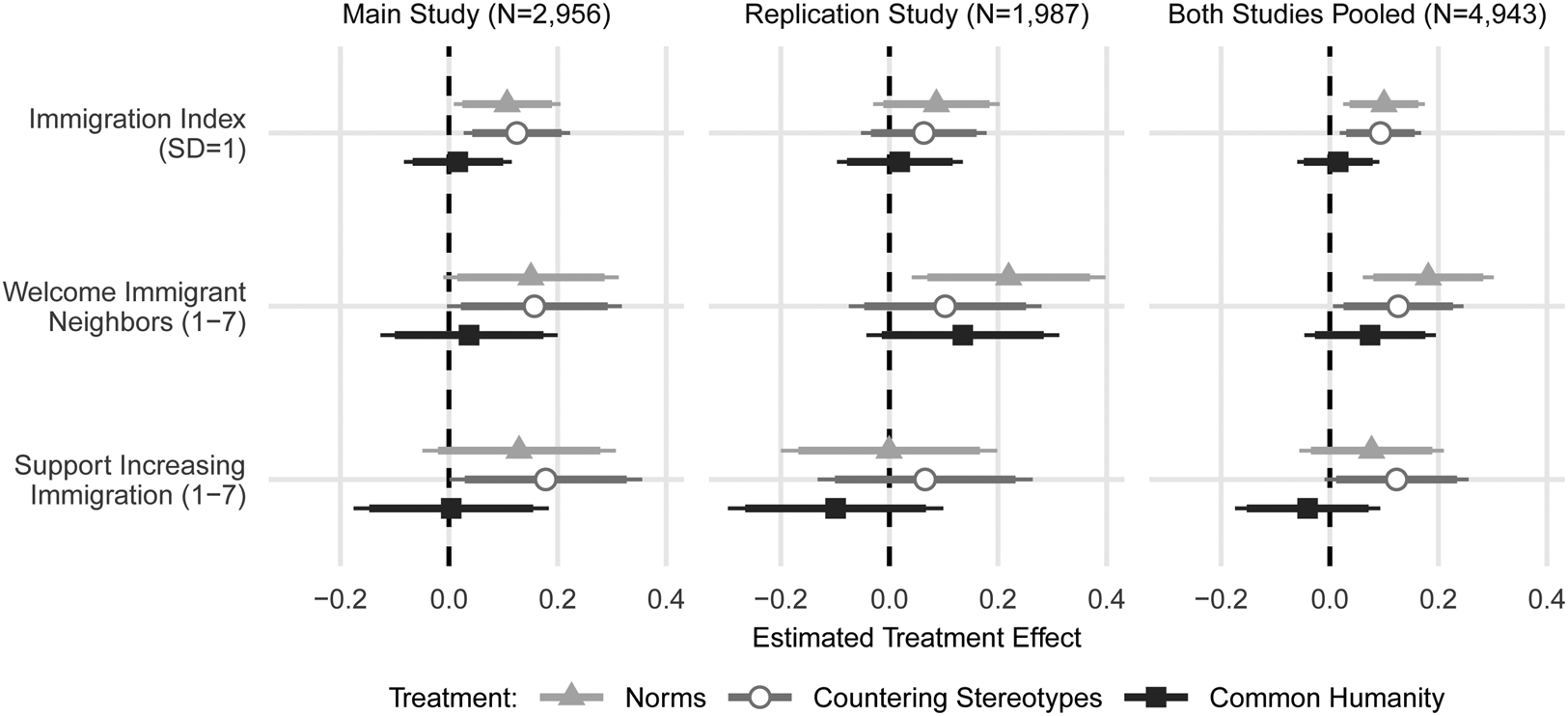

Figure 2 presents the estimated effects of our three political speech treatments on tolerance of immigrants as measured by our attitudinal outcomes: Immigration Index, Immigrant Neighbors, and Increase Immigration.Footnote 15 The left-hand panel focuses on our Main Study, the central panel on the Replication Study, and the right-hand panel uses pooled data from both studies.

Fig. 2. Treatment effects on tolerant attitudes.

Note: Points indicate effect estimates with 95 percent (thin) and 90 percent (thick) confidence intervals. Immigration Index is scaled to have a standard deviation of one and the two outcome variables are measured on seven-point scales.

Turning first to our Main Study, for the index measure (left panel, top), the Norms and Countering Stereotypes treatments produce positive and statistically significant effects. Specifically, the estimated effects are 0.11 ($\rm {p} = 0.03$![]() ) for Norms and 0.12 ($\rm {p} = 0.01$

) for Norms and 0.12 ($\rm {p} = 0.01$![]() ) for Countering Stereotypes. As Immigration Index has a standard deviation of one by design, these effect sizes approximately equal 10 percent of a standard deviation. In contrast, we see no evidence of an effect for the Common Humanity treatment (est. $= 0.02$

) for Countering Stereotypes. As Immigration Index has a standard deviation of one by design, these effect sizes approximately equal 10 percent of a standard deviation. In contrast, we see no evidence of an effect for the Common Humanity treatment (est. $= 0.02$![]() , $\rm {p} = 0.75$

, $\rm {p} = 0.75$![]() ).

).

The disaggregated results for Immigrant Neighbors (left panel, center) and Increase Immigration (left panel, bottom) reinforce these inferences. Openness toward Immigrant Neighbors is increased by the Norms and Countering Stereotypes treatments (effects of 0.15, $\rm {p} = 0.07$![]() and of 0.16, $\rm {p} = 0.06$

and of 0.16, $\rm {p} = 0.06$![]() , respectively). These two treatments also raise tolerance as measured with Increased Immigration by 0.13 ($\rm {p} = 0.16$

, respectively). These two treatments also raise tolerance as measured with Increased Immigration by 0.13 ($\rm {p} = 0.16$![]() , Norms), and 0.18 ($\rm {p} = 0.05$

, Norms), and 0.18 ($\rm {p} = 0.05$![]() , Countering Stereotypes). In each case, these effects approximately equal 10 percent of a standard deviation in our outcome measure, similar to the effect sizes we documented for Immigration Index. As before, the estimated effect of the Common Humanity treatment on both outcomes is far from statistical significance and substantively very small (0.04, $\rm {p} = 0.66$

, Countering Stereotypes). In each case, these effects approximately equal 10 percent of a standard deviation in our outcome measure, similar to the effect sizes we documented for Immigration Index. As before, the estimated effect of the Common Humanity treatment on both outcomes is far from statistical significance and substantively very small (0.04, $\rm {p} = 0.66$![]() ; 0.01, $\rm {p} = 0.97$

; 0.01, $\rm {p} = 0.97$![]() ).

).

To summarize the Main Study's results, we find weak evidence of effects for the Norms and Countering Stereotypes treatments but no evidence for effects of the Common Humanity treatment. These results hold when not adjusting for covariates and when only adjusting for imbalanced covariates (see Table S.7). An additional exploratory analysis produces no evidence of subgroup heterogeneity in our Main Study (see Table S.10): out of 21 interactions between treatments and covariates, only one is significant—roughly what would be expected in the absence of heterogeneity based on the definition of p-values. We also performed in-depth analyses of heterogenous effects along three covariates: partisanship, education, and news attention. We do not find that Democrats and Republicans respond differently to our treatments (see SI 4). We do, however, find weak evidence that independents react more strongly to our treatments. This result may reflect partisans’ tendency to discount messages from sources that they are not sure belong to their party (Taber and Lodge, Reference Taber and Lodge2006). For education, the estimates do not show consistent heterogenous effects, while we do find suggestive evidence that respondents who pay the most attention to the news react most strongly to our treatments (see SI 5).

The central panel of Figure 2 reports the results from the Replication, conducted one year later with roughly 2000 respondents and treatments and outcome measures that exactly match the Main Study.Footnote 16 As in the Main Study, the Norms and Countering Stereotypes treatments tend to increase our three measures of tolerance toward immigrants, while the direction of the effect of the Common Humanity treatment is inconsistent, although never statistically significant. Compared to the Main Study, the Replication's treatment effects are often smaller and less precisely estimated, although there are no statistically significant differences in effect size between the two studies (see Table S.9).

In a final step, we pool responses from both studies (right-hand panel of Figure 2). Pooling maximizes statistical power without affecting the internal validity of our analyses because both studies included exactly the same treatments, outcomes, and covariates. As before, we find that tolerance, as measured by Immigration Index, is increased by the Norms and Countering Stereotypes treatments (est. = 0.10, $\rm {p}< 0.01$![]() and est. = 0.09, $\rm {p}< 0.05$

and est. = 0.09, $\rm {p}< 0.05$![]() , respectively), but not by political speech that stresses Common Humanity (est. $= 0.02$

, respectively), but not by political speech that stresses Common Humanity (est. $= 0.02$![]() , $\rm {p} = 0.69$

, $\rm {p} = 0.69$![]() ). This pattern is repeated for Immigrant Neighbors. The effects here are 0.18 ($\rm {p}< 0.01$

). This pattern is repeated for Immigrant Neighbors. The effects here are 0.18 ($\rm {p}< 0.01$![]() ), 0.14 ($\rm {p}< 0.05$

), 0.14 ($\rm {p}< 0.05$![]() ), and 0.07 ($\rm {p} = 0.22$

), and 0.07 ($\rm {p} = 0.22$![]() ) for Norms, Countering Stereotypes, and Common Humanity, respectively. Finally, Increased Immigration is positively affected by the Countering Stereotypes (est. $= 0.12$

) for Norms, Countering Stereotypes, and Common Humanity, respectively. Finally, Increased Immigration is positively affected by the Countering Stereotypes (est. $= 0.12$![]() , $\rm {p} = 0.07$

, $\rm {p} = 0.07$![]() ) treatment, and the effect of Norms is also positive but less precisely estimated (est. $= 0.08$

) treatment, and the effect of Norms is also positive but less precisely estimated (est. $= 0.08$![]() , $\rm {p} = 0.26$

, $\rm {p} = 0.26$![]() ), while Common Humanity has an imprecisely estimated negative effect (est. $= -0.04$

), while Common Humanity has an imprecisely estimated negative effect (est. $= -0.04$![]() , $\rm {p} = 0.55$

, $\rm {p} = 0.55$![]() ).

).

Overall, we conclude that pro-immigrant political speech stressing Norms and Countering Stereotypes can enhance attitudinal tolerance toward immigrants, but that these effects are small—likely less than 10 percent of a standard deviation—and, consequently, that they can only be reliably detected in larger samples. In contrast, the Common Humanity treatment consistently produced null results, leading us to believe that it cannot expand tolerant attitudes. These differential effects across treatments echo the findings of a recent study, which shows that activists can best increase public support for immigration by appealing to American values (which bears similarities to our norms treatment), while appealing to human rights (similar to our common humanity treatment) does not help and may even be counterproductive (Voss et al., Reference Voss, Silva and Bloemraad2019). Further exploring the reasons behind the divergent effects of different types of pro-immigrant political speech is beyond the scope of our study, but offers an interesting avenue for future research.

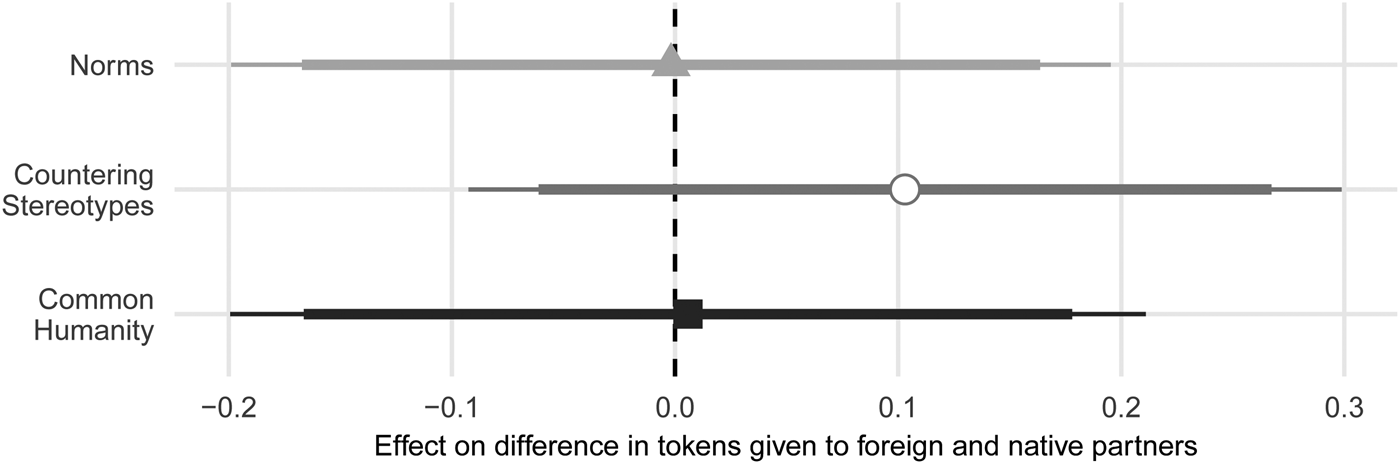

3.3 Effects on behavior toward immigrants

We now turn to the effect of pro-immigrant political rhetoric on behavior toward immigrants in the trust game embedded in the Main Study. Figure 3 reports estimates of our treatments’ effects in reducing the difference in tokens given to native-born and foreign-born partners during the game (full regression results are given in Table S.11). We find no evidence of treatment effects. The estimated coefficients are substantively very small (Countering Stereotypes: 0.10, which suggests that this treatment reduced in-group bias by about one-tenth of a token compared to the control group, Common Humanity: 0.01, and Norms: $-$![]() 0.00). None of these estimates approach statistical significance.

0.00). None of these estimates approach statistical significance.

Fig. 3. Treatment effects on trust game behavior.

Note: Points indicate effect estimates with 95 percent (thin) and 90 percent (thick) confidence intervals. The outcome variable ranges from 0 to 10.

There is no evidence that these null results reflect a failure by respondents to understand the game. They spent an average of 95 seconds reading the instructions, and 70 percent of them changed the number of tokens they gave across rounds. Furthermore, Table S.11 shows a significant effect of playing with a female partner, indicating that respondents did base play on partner characteristics. Since the trust game preceded our attitudinal items, it is also implausible that any treatment effects had “worn off” by the time respondents played it.

Moreover, these null results do not appear to arise from the ex ante absence of a trust differential in native compared to foreign-born partners. Respondents in the control group gave native-born partners an average of 5.32 tokens and foreign-born partners an average of 5.08 tokens, a statistically significant difference of 0.24 tokens ($\rm {p} = 0.03$![]() ). Among this same set of respondents, those who played all four rounds of the trust game with native-born partners gave 5.03 tokens on average, while those who played all rounds against foreign-born partners gave 4.52 tokens on average, a difference of 0.51 tokens ($\rm {p} = 0.09$

). Among this same set of respondents, those who played all four rounds of the trust game with native-born partners gave 5.03 tokens on average, while those who played all rounds against foreign-born partners gave 4.52 tokens on average, a difference of 0.51 tokens ($\rm {p} = 0.09$![]() ).Footnote 17

).Footnote 17

Further analyses in SI 1.6 reinforce the conclusion that the treatments did not promote trust in the behavioral game. As a robustness test, we estimated treatment effects for Tokens Given to foreign-born partners (i.e., only analyzing rounds played with foreign-born partners) and find no effects. We also find no effects in an exploratory analysis of sub-group heterogeneity (analysis not pre-registered) and no evidence that our treatments indirectly influenced behavior by altering perceptions of the acceptability of intolerance. Given these results, we excluded the behavioral game from the Replication.

In sum, we find no evidence that pro-immigrant political speech increased behavioral trust in immigrants. These null results are consistent with evidence that attitudes and behavior toward other, similarly stigmatized out-groups are often only weakly correlated (Talaska et al., Reference Talaska, Fiske and Chaiken2008). Racial stereotypes, for instance, affect interactions with racial minorities even among respondents who endorse equal treatment (Devine and Elliot, Reference Devine and Elliot1995), and recent experimental research shows that employers’ attitudinal support for hiring applicants with criminal records only weakly correlates with their behavioral choices in employment processes (Pager and Quillian, Reference Pager and Quillian2005). This highlights the importance of testing the scope of tolerance-enhancing interventions—political speech alters attitudes, our results suggest, but fails to change behavior.

4. Conclusion

We set out to explore whether political speech can increase tolerance toward immigrants. Our study took care to distinguish the effects of three messages that political speech can contain (i.e., stressing common humanity with immigrants, stressing norms of acceptance of diversity, and countering negative stereotypes), each theorized to foster tolerance by affecting beliefs about in- and out-groups. Our results provide mixed evidence about the ability of these forms of political speech to expand tolerance. With regard to behavior toward non-natives, the results are unambiguously null. For attitudes, we find that speech focusing on norms of tolerance and countering stereotypes can be effective, while speech emphasizing common humanity is not. Even for the former two types of speech, however, the effects are relatively small and only achieve statistical significance in larger samples. Overall, we conclude that political speech has some limited potential to foster tolerance toward immigrants.

A key strength of our study is that our treatments represent realistic exposure to political speech: they use real speech and keep exposure short, replicating the brevity of politicians’ quotes in newspaper articles or news coverage. Our finding that passive consumption of political speech only weakly promotes tolerant attitudes is intuitively plausible in the context of the literature that documents on the relative stability and persistence of anti-immigrant predispositions (Fielding, Reference Fielding2018) and out-group prejudice (Katz, Reference Katz1976; Kinder and Sears, Reference Kinder and Sears1981; Henry and Sears, Reference Henry and Sears2009). It also complements recent research on what works in reducing phenomena like stereotyping, intolerance, and negative attitudes toward another group, which shows large and lasting effects of more intensive interventions involving active participation (Broockman and Kalla, Reference Broockman and Kalla2016; Simonovits et al., Reference Simonovits, Kezdi and Kardos2018). Future research could additionally explore whether “stronger treatment,” i.e., more active engagement with pro-immigrant political speech (e.g., in the context of party conferences, town hall meetings, or political demonstrations), or repeated exposure to this type of political speech more effectively enhances tolerances than our treatments.

Our study also highlights a striking asymmetry: while multiple pieces of research establish that even brief xenophobic appeals increase exclusionary attitudes toward immigrants, our findings suggest that pro-immigrant political speech has a much harder time decreasing such attitudes and—depending on the message—may not succeed at all. This contrast begs further questions. Is negative speech more potent than positive speech? Recent research on the negative versus positive media framing of immigrants suggests that it might be (Haynes et al., Reference Haynes, Merolla and Ramakrishnan2016). Is this asymmetry confined to the immigration context alone or does it apply to other types of intergroup relations? Does positive speech have systematic effects that differ from those that we investigate, for instance, does it affect political mobilization? These questions call for future research.

Rising anti-immigrant speech and waning pro-immigrant speech in the real world enhance this study's relevance. Our results do not suggest that pro-immigrant speech is the silver bullet in tackling exclusionary attitudes, but they do suggest that such speech is not completely toothless either. Appealing to norms of tolerance and countering negative stereotypes about immigrants can contribute to keeping anti-immigrant hostility at bay. Given this, it is possible that the greater presence of pro-immigrant political speech until recently served to as a bulwark for tolerance, and that for politicians to abandon such statements altogether may lead to normatively troubling consequences.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2021.37.