1. Introduction

A significant share of politicians only spend a limited time in office and then exit through the so-called revolving door. They take up jobs as lobbyists or sit on boards of directors, where they earn their legislator salary several times over (e.g., Hillman, Reference Hillman2005; Lester et al., Reference Lester, Hillman, Zardkoohi and Cannella2008; Lazarus et al., Reference Lazarus, McKay and Herbel2016; Palmer and Schneer, Reference Palmer and Schneer2016). Given the increasing importance of the revolving door, a growing literature tries to determine what drives it. The prevailing explanations focus on the human capital of former politicians, in particular on whether they are hired because of their expertise or because of their connections (cf. de Figueiredo and Richter, Reference de Figueiredo and Richter2014). These arguments provide answers to the question why employers want to hire former lawmakers. They therefore focus on the demand-side of the revolving door, taking it as given that there is a supply of politicians who want to leave politics to go into the private sector. One reason for this is that existing studies almost exclusively examine the recent US Congress. While it is true that many legislators in this particular environment are happy to leave electoral politics and go through the revolving door, we know little about the conditions under which this is true in general.

In this paper, I complement the demand-side explanation by demonstrating the importance of the supply-side of the revolving door. Based on a simple cost-benefit framework that outlines the conditions under which politicians are willing to leave office and go into the private sector, I argue that one important institutional factor that influences their decision is campaign finance legislation. Politicians can not only benefit from special interest money by taking up a lucrative job upon exiting office, they can also bolster their chances of staying in office through campaign spending. Better reelection odds affect lawmakers' career decision calculus, making it less attractive to go through the revolving door. This suggests an implicit trade-off at the individual level between special interest money in the form of campaign spending and as a revolving door salary. The boost that campaign spending can provide to lawmakers depends on the regulatory environment they operate in, and in particular on campaign finance legislation. More permissive rules allow them to raise and spend more money, making it more likely that they are able to stay in office. I therefore argue that legislators should be more prone to leave office and go through the revolving door in environments with stringent campaign finance regulation, whereas permissive rules should result in less movement into the private sector.

I test this supply-side mechanism of the revolving door by exploiting a change in campaign finance regulation that was exogenously imposed on legislators. The US Supreme Court's Citizens United ruling in 2010 invalidated existing laws that prevented independent campaign expenditures by corporations and unions, leading to an increase of such spending in subsequent elections (Spencer and Wood, Reference Spencer and Wood2014; Klumpp et al., Reference Klumpp, Mialon and Williams2016; Abdul-Razzak et al., Reference Abdul-Razzak, Prato and Wolton2018; Petrova et al., Reference Petrova, Simonov and Snyder2019). Some states had laws that were affected by the ruling, while others had no such restrictions on their books. This allows me to use a difference-in-differences design to estimate the effect of a change in campaign finance laws on the prevalence of the revolving door. Using information from the states' disclosure agencies, I create new comparative data that track more than 8000 state representatives between 2006 and 2013 and record whether they left office and were subsequently registered as lobbyists.

I show that, consistent with my theoretical argument, the removal of restrictions on independent campaign spending caused a significant drop in the probability that members of state legislatures left politics to become lobbyists. The decrease was driven by fewer incumbents voluntarily leaving office to take up a position in the private sector, while there was no effect on the frequency with which incumbents became lobbyists after a lost election. This suggests that the change came through incumbents' conscious decisions to forgo a lobbyist salary and instead make use of the higher campaign spending.

I also demonstrate that the loosening of campaign finance laws had more pronounced effects on subsets of politicians that can be expected to benefit more from special interest spending. First, the drop in the likelihood of leaving office to go through the revolving door was larger among Republicans, who benefited to a greater degree from the increase in independent campaign spending after Citizens United. Second, existing evidence shows that less influential and connected politicians receive fewer campaign contributions and are also less likely to go through the revolving door. Consistent with this, Citizens United had no effect on the probability that incumbents left office without subsequently taking up a lobbyist job. Finally, I provide evidence that the Supreme Court ruling did not affect the overall demand for lobbyists.

The results demonstrate that the revolving door is not only influenced by demand-side factors such as politicians' expertise or connections, but also by supply-side considerations, which in turn are driven by the institutional environment. This finding makes several contributions. First, it advances the burgeoning literature on the revolving door. The prevalent demand-side approach has provided valuable insights into which lawmakers within a legislature are most likely to go through it. However, it has difficulty explaining differences between legislatures. The revolving door is more common in some countries than in others, and I show below that there are differences between the US states as well. However, it is unlikely that private sector actors need expertise or connections in some countries or states, but not in others. A supply-side approach opens the door to comparative investigations, leading to a better understanding of the conditions under which the practice is common.

Second, the paper adds to the literature on the consequences of campaign finance legislation. Existing research examines the effects of more or less stringent rules on the amount of campaign spending and its effectiveness (Stratmann, Reference Stratmann2006; Spencer and Wood, Reference Spencer and Wood2014) as well as the consequences this has on various outcomes (e.g., Werner, Reference Werner2011; La Raja and Schaffner, Reference La Raja and Schaffner2014, Reference La Raja and Schaffner2015; Potter and Tavits, Reference Potter and Tavits2015; Barber, Reference Barber2016; Hall, Reference Hall2016; Klumpp et al., Reference Klumpp, Mialon and Williams2016). I contribute to this body of research by showing that campaign finance laws also have an effect on other forms of money in politics, such as the revolving door.

This means that, finally, the paper adds to the literature on money in politics more broadly. Most studies focus on a single form of money in isolation. But as I show here, different types of spending are related. By demonstrating that campaign finance laws have an effect on revolving door employment, the paper contributes to a growing literature on the connections between different forms of money in politics (e.g., Issacharoff and Karlan, Reference Issacharoff and Karlan1998; Naoi and Krauss, Reference Naoi and Krauss2009; Harstad and Svensson, Reference Harstad and Svensson2011; La Raja and Schaffner, Reference La Raja and Schaffner2015). It also adds to scholarship addressing the connection between lobbying and campaign money (Bennedsen and Feldmann, Reference Bennedsen and Feldmann2006; Campos and Giovannoni, Reference Campos and Giovannoni2007) and relates work on campaign spending to work on the causes and consequences of political connections (Faccio, Reference Faccio2006; Eggers and Hainmueller, Reference Eggers and Hainmueller2009).

2. Campaign Finance Legislation and the Supply-Side of the Revolving Door

Companies that hire former politicians are more successful in pushing for favorable legislation and have higher firm valuations (Baumgartner et al., Reference Baumgartner, Berry, Hojnacki, Kimball and Leech2009; Luechinger and Moser, Reference Luechinger and Moser2014). It is thus not surprising that there is a demand in the private sector for the services of ex-politicians. Accordingly, most of the literature examines whether they are valuable because of their expertise or because of their connections (e.g., Esterling, Reference Esterling2004; Hillman, Reference Hillman2005; Parker, Reference Parker2008; LaPira and Thomas, Reference LaPira and Thomas III2014).Footnote 1

But there is another side to a revolving door move that is largely ignored: Why are so many politicians willing to leave public service for the private sector? One reason this question has not been answered so far is the literature's focus on single institutional environments where the revolving door exists in the first place, most prominently the contemporary US Congress. But it has not always been the case that there is a ready supply of politicians willing to leave office for a private sector job. Mayhew (Reference Mayhew1974) famously described members of Congress as behaving like single-minded seekers of reelection. And at the time, few lawmakers went through the revolving door (Lazarus et al., Reference Lazarus, McKay and Herbel2016). Contrast this with Tennessee Representative Jim Cooper's view of his colleagues today: “Serving the public used to be considered the highest calling; now, many see it as a stepping stone to lucrative lobbying careers.”Footnote 2 The demand-side approach cannot easily explain why this change occurred, as presumably politicians in the past also possessed expertise and connections of value to the private sector.

The same is true for cross-sectional differences. Besides the United States, the revolving door has been documented in countries such as the United Kingdom or Ireland (Eggers and Hainmueller, Reference Eggers and Hainmueller2009; González-Bailon et al., Reference González-Bailon, Jennings and Lodge2013; Baturo and Arlow, Reference Baturo and Arlow2018). But it is notably absent in many other countries, where politicians instead try to stay in politics for as long as possible, either in the same position or by cycling through different offices (see e.g., Samuels, Reference Samuels2003). What is more, I show below that there are large differences in how prevalent the revolving door is between the US states. Again, it seems unlikely that special interests need expertise or connections in some countries or states, but not in others. Demand-side accounts thus have difficulty explaining differences in the prevalence of the revolving door across time and space. Under what conditions are politicians willing to leave behind a career dedicated to representing the interests of their constituents in favor of one representing the interests of certain companies or industries?

2.1. The Supply-Side of the Revolving Door

To understand why the revolving door is a phenomenon in some contexts but not in others, we need to understand what drives the supply of politicians willing to go through it. A useful starting point are classic accounts of candidacy and reelection decisions (e.g., Rohde, Reference Rohde1979; Groseclose and Krehbiel, Reference Groseclose and Krehbiel1994). A politician is thought to run for office again in the next election if P · B − C > 0, where P is the probability of winning, B is the benefit of holding office, and C is the cost of running. This inequality normalizes the utility of being out of office to zero. We can instead explicitly incorporate the benefits of a revolving door job, expanding the calculus as follows:

If an incumbent runs for reelection, they win with probability P and get office benefits B. They lose with probability 1−P, in which case they can take-up a private sector job which gives them utility S L. If an incumbent does not run for reelection and voluntarily goes through the revolving door, they receive utility S V. S L and S V may be different or the same.

Equation 1 provides a simple framework to guide the study of the revolving door's supply-side. The comparative statics are straightforward: incumbents are more likely to not run for office and instead take up a revolving door job if their chances of winning reelection are low, if the benefits of holding office are low, if the costs of running for reelection are high, and if the benefits from holding a revolving door job are high.

The equation allows us to think about how different institutional environments affect whether incumbents go through the revolving door. This makes it possible to study the phenomenon in a comparative manner and explain how common it is in different places and at different times. In the next section, I lay out the argument for why campaign finance legislation is one important institutional factor that should influence the prevalence of the revolving door.

2.2. Campaign Finance Legislation and the Revolving Door

Because campaign spending improves reelection prospects (cf. Jacobson, Reference Jacobson2015), lawmakers try to gain financial support from special interests. However, the ability to benefit from campaign money is not equally distributed. In many countries, the United States among them, incumbents have a significant advantage (e.g., Krasno et al., Reference Krasno, Green and Cowden1994; Hogan, Reference Hogan2000; Magee, Reference Magee2012; Fouirnaies and Hall, Reference Fouirnaies and Hall2014; Jacobson and Carson, Reference Jacobson and Carson2016). As a consequence, campaign finance legislation that curbs politicians' ability to raise or spend election funds typically constrains officeholders more than challengers, leading to lower reelection rates for the former, both in theUnited States and elsewhere (Hogan, Reference Hogan2000; Milligan and Rekkas, Reference Milligan and Rekkas2008; Avis et al., Reference Avis, Ferraz, Finan and Varjão2017; Fouirnaies, Reference Fouirnaies2018).

One implication of this is that the decision in Equation 1 should be influenced by campaign finance legislation through its effect on P.Footnote 3 An incumbent in an environment in which there are few restrictions can raise a lot of money and benefit from a robust advertising campaign to mobilize potential voters. This gives her a good chance to win another term (high P) and enjoy the benefits she derives from being in office. In contrast, if laws prevent a politician from spending a lot of campaign money, her chances for reelection are diminished (low P). This makes it comparatively less attractive to take on the cost of running another campaign, in particular if there is a lucrative outside option. Lawmakers should thus be more likely to go through the revolving door in environments with stringent campaign finance regulation, whereas permissive rules should result in less movement into the private sector. This implies that campaign finance reforms can have unintended consequences, leading to countervailing movements for other ways in which money enters politics.

Of course, not every incumbent will be equally affected by changes in the legal framework. Some legislators are close to special interests, so restrictive regulations limit their spending and looser laws should lead to a significant shift in their P. By contrast, others are not as much on the radar of moneyed groups and benefit less from campaign spending. More permissive rules will not help them, since they were unlikely to be constrained by the old regulation to begin with.

In summary, I argue that the permissiveness of campaign finance regulation is an important factor determining the supply of politicians going through the revolving door. Looser laws should lead to a slowdown of movement into the private sector, but with significant heterogeneity depending on legislators' importance to special interest groups. In the next section, I describe the empirical setting in which I study this argument and lay out the specific predictions it implies.

3. Empirical Context: Citizens United versus FEC

To identify the effect of the permissiveness of campaign finance laws on the revolving door, I exploit the Supreme Court's 2010 Citizens United decision. The ruling changed campaign finance laws for some states but not for others, in a way that was exogenous to the legislators affected by it. The original lawsuit narrowly challenged some provisions of the 2002 Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act (BCRA). The BCRA extended existing restrictions on “express advocacy” campaign advertisements (which directly campaign for or against the election of a specific candidate and could not be funded by corporate or union contributions) to also apply to “electioneering communication,” which are advertisements that target voters and refer to candidates for office, but do not explicitly advocate for or against their election.

Citizens United, a conservative non-profit organization, had produced a movie critical of Hillary Clinton and wanted to distribute it through TV on demand. Because the movie was electioneering communication and funded by corporate donations, this was prohibited by the BCRA. The group thus legally challenged the ban on corporate and union spending for electioneering communication. After the oral argument, the Supreme Court, in a surprise move, announced that it would rehear the case to scrutinize not just the narrow provisions of the BCRA challenged by Citizens United, but also the ban on independent expenditures for express advocacy (Spencer and Wood, Reference Spencer and Wood2014).

A second oral argument followed, after which the court ruled with a 5-4 majority that restrictions on both electioneering communication and express advocacy were unconstitutional. Corporations and unions were henceforth allowed to spend unlimited amounts of money on campaign advertisements, as long as this was done independently of candidates. In practice, however, the rules prohibiting coordination between the campaigns and the groups that do this independent spending, such as Super PACs or 501(c) organizations, are rather porous. For example, candidates typically endorse “their” Super PAC, which are often run by former staffers (Spencer and Wood, Reference Spencer and Wood2014; Dawood, Reference Dawood2015). The significance of the ruling was enhanced when shortly thereafter, the District Court for the District of Columbia ruled in SpeechNow.org versus FEC that individuals and organizations were allowed to contribute without limits to groups that make independent expenditures.

While the Supreme Court ruling only dealt with federal law, by extension, it also applied to any state regulation that limited or prohibited independent expenditures by corporations or unions. Table 1 lists the states in which laws were in response either directly repealed by the legislatures or invalidated and not enforced by the states' campaign finance bodies. The other states did not have legislation affected by Citizens United. This means that legislators in some states saw themselves subject to looser campaign finance regulation, while for others the laws did not change. I will use this fact to identify the impact of campaign finance legislation on the revolving door. In the Online Appendix, I provide a detailed discussion of the states included in Table 1, consider alternative coding decisions, and demonstrate that all empirical results are robust to them.

Table 1. States affected by Citizens United. See the Online Appendix for a detailed discussion.

3.1. Effects of Citizens United on Campaign Spending and Election Results

Several existing studies examine the direct consequences of Citizens United. The first finding is that independent campaign spending increased. At the federal level, it grew by almost 600 percent from 2008 to 2012 (Hansen et al., Reference Hansen, Rocca and Ortiz2015). At the state level, independent spending increased to a greater degree in states that were affected by the ruling than in states that were not, indicating that the old limits were binding (Spencer and Wood, Reference Spencer and Wood2014; Hamm et al., Reference Hamm, Malbin, Kettler and Glavin2014; Abdul-Razzak et al., Reference Abdul-Razzak, Prato and Wolton2018).Footnote 4

A second finding is that this injection of money affected election outcomes. It had marked partisan effects, as it disproportionately benefited Republicans. In the lower chambers, their probability of getting reelected increased by 3–4 percentage points (Klumpp et al., Reference Klumpp, Mialon and Williams2016; Abdul-Razzak et al., Reference Abdul-Razzak, Prato and Wolton2018). Note that this is the average effect across all races, so it does not mean that only Republicans benefited from increased campaign spending on their behalf. Indeed, outside spending grew to a greater extent in states affected by the Supreme Court ruling for both Democrats and Republicans, only more so for the latter (Abdul-Razzak et al., Reference Abdul-Razzak, Prato and Wolton2018).

Citizens United thus had a direct and visible effect on campaign spending, which in turn improved the chances of being reelected for many legislators. In other words, the Supreme Court ruling had an effect on P in Equation 1. Building on these findings, I now investigate whether Citizens United had knock-on effects on revolving door employment.

3.2. Theoretical Expectations

The argument that I made above suggests that the impact of the change in campaign finance law brought about by Citizens United does not end with its effect on P. The increased chance of winning reelection should make it more attractive to run again, which in turn should decrease the appeal of a revolving door job. The main hypothesis I test is therefore that the Supreme Court ruling led to a decrease in the probability that incumbents left office and went through the revolving door.

I have also argued that not every legislator is equally affected. For some, Citizens United led to a large increase in campaign spending on their behalf, which should boost their P significantly. Other legislators are not as close to special interests, so a change in campaign finance regulation has less of an effect on their P. Unfortunately, this is not empirically observable at the individual level, as pre-ruling campaign spending data are right-censored by the existing restrictions; and post-ruling data are incomplete due to the lack of disclosure laws for independent spending in many states. There are, however, indirect implications that should manifest themselves in two types of heterogeneous effects.

First, we should see different effects by partisanship. Studies consistently show that Republicans benefit more from permissive campaign finance laws, both in general and in the specific case of Citizens United (Hall, Reference Hall2016; Klumpp et al., Reference Klumpp, Mialon and Williams2016; Abdul-Razzak et al., Reference Abdul-Razzak, Prato and Wolton2018). As a consequence, we can expect that a relaxation of campaign finance regulation dampens the propensity of Republican legislators to go through the revolving door to a greater degree than is the case for Democrats.

Second, research shows that influential and well-connected incumbents receive more campaign spending and are also more likely to go through the revolving door (cf. Lazarus et al., Reference Lazarus, McKay and Herbel2016; Fouirnaies and Hall, Reference Fouirnaies and Hall2018). In other words, some legislators engage a lot with special interests, so they benefit from significant campaign contributions while in office and also have a high probability of taking up a revolving door job. Removing restrictive laws should have an effect on the career paths of these politicians. Other legislators benefit less from campaign spending and are also unlikely to go through the revolving door. Restrictive campaign finance laws do not represent much of a constraint on them, so making regulation more permissive is of little consequence. The empirical implication of this argument is that a change in campaign finance regulation should have an effect on the propensity of legislators to leave office and go through the revolving door, but not on the probability that incumbents retire without taking up a revolving door job.

4. Data and Research Design

4.1. Data: The Revolving Door in the US States

So far, data on the revolving door exist at the national level only. I assemble the first dataset that tracks whether state legislators left office and subsequently took up a lobbyist position. Information on legislators comes from Klarner et al. (Reference Klarner, Berry, Carsey, Jewell, Niemi, Powell and Snyder2013) and Klarner (Reference Klarner2013). Existing research shows that Citizens United affected results in state houses only (Klumpp et al., Reference Klumpp, Mialon and Williams2016), so I focus on the lower chambers.Footnote 5 I follow the convention in the literature and exclude members of Nebraska's unicameral, non-partisan legislature. Using the elections from 2006 to 2012, this produces a sample of 8349 state representatives (4050 Democrats, 4299 Republicans).

To determine whether they went through the revolving door, I link the legislator data with a list of all registered state lobbyists for the years 2006–2013. Information comes from the official lobbyist registries, published by the respective state disclosure agencies and compiled by the National Institute on Money in State Politics.Footnote 6 To connect the legislator data with the lobbyist information, I use a two-step procedure designed to minimize both false positives and false negatives. First, I employ an automated name matching algorithm.Footnote 7 I set a low similarity threshold to minimize the number of false negatives. Because this leads to a large number of false positives, in a second step I check all matches manually, using supplementary information from internet searches when necessary. The unit of observation is the legislator–election cycle, and there are four time periods: 2006–07, 2008–09, 2010–11, and 2012–13. For each cycle, I record whether a politician left office and became a registered lobbyist in the state the same or the following calendar year.Footnote 8

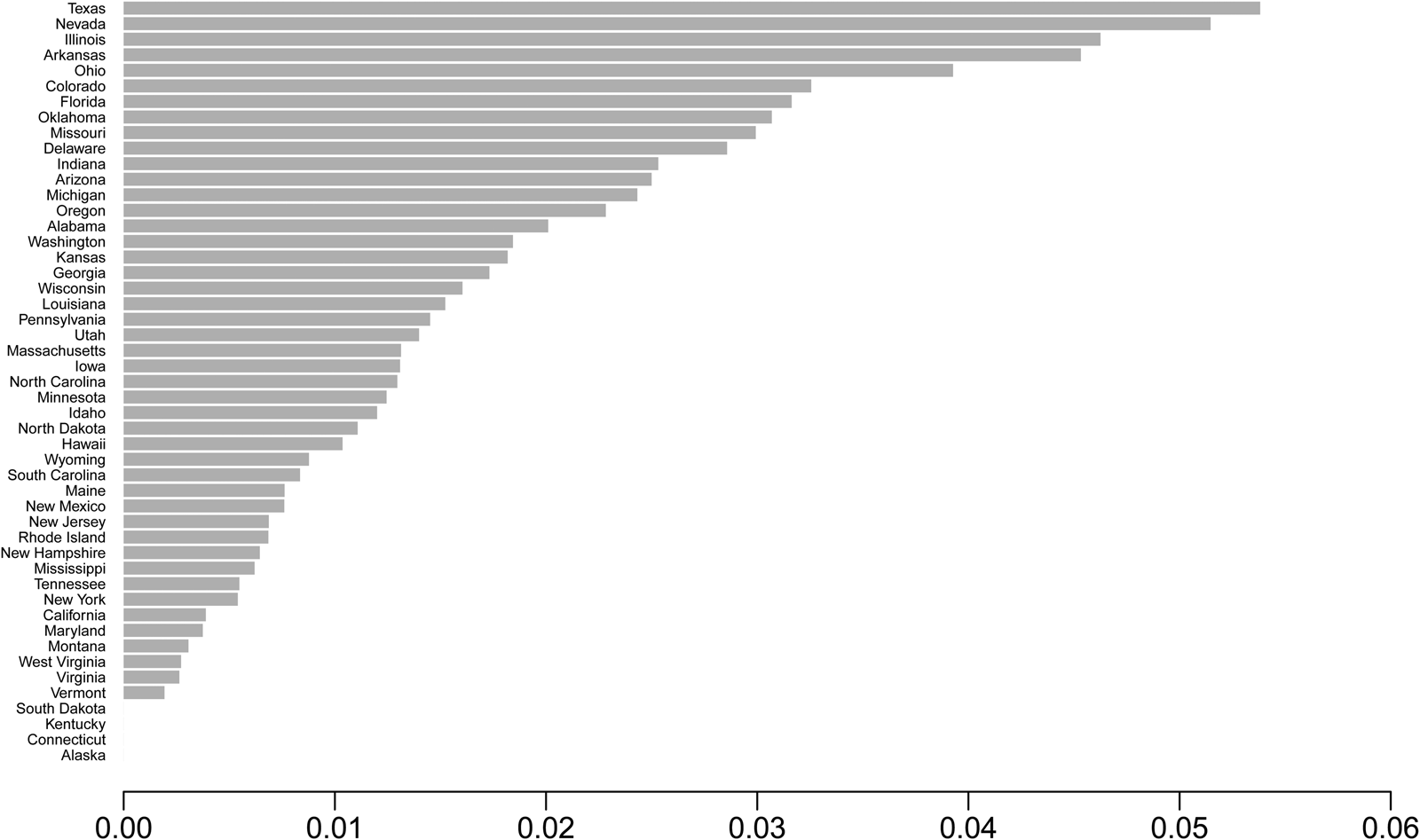

Figure 1 plots the state-wise proportion of representatives per election cycle who leave office and are subsequently registered as lobbyists. It reveals that there are large differences between states. The revolving door is most common in Texas, where on average 5.4 percent of sitting representatives per election cycle go through the revolving door. Other states in which movement from the state house into lobbying positions is common are Nevada (5.1 percent), Illinois (4.6 percent), and Arkansas (4.5 percent). On the other end, there are four states (Alaska, Connecticut, Kentucky, and South Dakota) in which no legislators registered as lobbyists in the year of exiting or the one thereafter. Note that these are probabilities unconditional on leaving office. Other studies and news stories often report the probability of becoming a lobbyist conditional on exiting, which in Congress has been between 30 and 40 percent in recent years (Lazarus et al., Reference Lazarus, McKay and Herbel2016). Given that between 10 and 20 percent of House members depart in a given cycle, this implies unconditional probabilities between 3 and 8 percent, which is comparable to what we observe in many state legislatures.

Figure 1. Share of legislators per election cycle that leave office and are registered as lobbyists in the same or the following year.

4.2. Research Design: Difference-in-Differences

To estimate the effect of Citizens United on the revolving door, I use a difference-in-differences model of the following form:

where i indicates a legislator, s a state, and t an election cycle. To analyze the different ways of leaving office and taking up a revolving door job, I use several dependent variables. In the basic specification, y ist takes the value of one if a legislator leaves office and registers as a lobbyist in the same or following year. This combines taking up a revolving door job after leaving office voluntarily as well as after a lost reelection bid. I also present specifications distinguishing between these two ways. For the “voluntary” route, y ist is one if an incumbent does not run for reelection or resigns during a term and subsequently registers as a lobbyist; for the “insurance” route it is one if an incumbent runs again, loses, and then goes through the revolving door. Finally, I also estimate specifications in which y ist takes the value of one if a legislator leaves office but does not register as a lobbyist within a year.

Because the decision of whether to leave politics and become a lobbyist is most relevant for legislators who are up for reelection, I restrict the main analyses to incumbents who have reached the end of a legislative term and have to run again to stay in office.Footnote 9 This results in a sample of 18,358 legislator–election cycles. Republicans are more likely to go through the revolving door than Democrats, which is consistent with evidence from the federal level.Footnote 10

Bans is a dummy variable indicating whether state s had a ban on independent corporate spending (see Table 1), and Post-CU t is a dummy that takes the value of one for the post-Citizens United election cycles of 2010–11 and 2012–13. The quantity of interest is β. State and election cycle fixed effects are indicated by γs and δt. The former absorb any time-invariant differences between states, such as the size of the legislature or lobbyist registration laws. The latter soak up any common time shocks, for example national trends in partisan support or general economic conditions. Together, the state and year fixed effects absorb the constituent terms of the interaction effect.

Time-variant differences between states are denoted by Z st. They are whether a state had a “cooling off” law that imposes waiting times on elected officials before they can become lobbyists;Footnote 11 whether there were term limits; and whether the state had a public campaign finance system.Footnote 12 A set of individual-level covariates is denoted by X ist. They are the number of years a legislator has spent in office, whether their party controlled the legislature, and whether they were in a speaker or party leadership position.

The assumption required for treatment effect identification in difference-in-differences designs is that of parallel trends. It has to be assumed that had Citizens United not occurred, the difference in the dependent variable between treatment and control states would have been the same as it was before the ruling. To relax this restrictive assumption, I include a set of state-specific linear time trends ξst (Angrist and Pischke, Reference Angrist and Pischke2009), as is standard in studies of the consequences of Citizens United (see Klumpp et al., Reference Klumpp, Mialon and Williams2016; Abdul-Razzak et al., Reference Abdul-Razzak, Prato and Wolton2018; Petrova et al., Reference Petrova, Simonov and Snyder2019). They capture secular trends that differ between states and may affect the dependent variable, for example their partisan composition or economic growth.Footnote 13 Finally, εist is the error term. I use a linear probability model, and parameter estimates are reported with robust standard errors clustered by state.

5. Results

What is the effect of removing campaign finance restrictions on the revolving door? The first column in Table 2 displays the treatment effect of Citizens United for members of state lower houses of both parties combined. Here, the dependent variable is one if a legislator leaves office (voluntarily or after a lost election) and subsequently registers as a lobbyist. Consistent with theoretical expectations, the treatment effect is negative and statistically significant. As a consequence of the court ruling, legislators in the affected states were about 2 percentage points less likely to go through the revolving door than they would have been otherwise. Given the baseline percentages in Figure 1, this is a substantial drop.

Table 2. Treatment effect β of Citizens United on the probability that a legislator will leave office and register as a state lobbyist.

*p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01. Regressions include state-level and individual-level controls, state and year fixed effects, and state-specific time trends. Robust standard errors clustered by state in parentheses.

This provides clear evidence that making campaign finance laws more permissive does not only affect the political landscape through its direct effect on elections. An indirect consequence is that the increase in campaign spending is accompanied by a substantial decrease in the probability that incumbents leave office to work as lobbyists.

5.1. Slowdown is Larger Among Republicans

I have argued that the effect of permissive campaign finance laws on the revolving door is not uniform. Special interests spend more resources on some politicians than on others. The ban on independent campaign spending will have been a greater constraint on incumbents who benefit from a lot of special interest money, and they should be more impacted by its removal. The first way this should manifest itself in the context of Citzens United is in partisan differences. Both Republican and Democratic legislators benefited from increased independent campaign spending after the ruling, but the former more so than the latter.

The second column of Table 2 shows the results of estimating the model for Republican legislators only. The treatment effect is indeed larger than in the sample as a whole. In the states affected by Citizens United, the probability that Republican representatives went through the revolving door was 2.7 percentage points lower post-treatment than it would have been otherwise.

The third column shows results from estimating the model only with Democrats. The point estimate of the treatment effect is negative and significant at conventional levels. Thus, a considerable number of Democrats also reacted to the loosening of campaign finance regulation by not going through the revolving door. However, the magnitude of the effect is only about half as large as for Republican legislators. Citizens United thus had heterogeneous partisan consequences in the way we would theoretically expect.

5.2. Effect is Driven by Voluntary Revolving Door Movement

Before moving on to the second hypothesized way in which the heterogeneous impact of a change in campaign finance legislation should manifest itself, I first examine whether the slowdown of the revolving door I have demonstrated so far is the result of a conscious choice of incumbents, or a mechanical byproduct of better reelection chances. There are two ways in which a change in P brought about by more permissive campaign finance laws could slow down the revolving door: Fewer politicians can voluntarily leave office and register as a lobbyist without running for reelection (S V); or fewer can go through the revolving door after a failed bid for reelection (S L).

If a decline in voluntary revolving door employment is the main mechanism, it suggests that there was a conscious decision by incumbents to forgo a lobbyist position because special interests can spend more campaign money on their behalf. That is, it would be evidence that in response to campaign finance legislation, lawmakers are trading off between the goals of being in office and earning more money. By contrast, if the findings in Table 2 are driven by the fact that fewer incumbents lose their reelection bids and therefore do not need to exercise their “insurance” option, the drop in revolving door employment is merely a mechanical side-effect of the change in legislation.

Table 3 shows the effects of Citizens United on both types of revolving door employment. The first three models examine the voluntary route. The dependent variable takes the value of one if an incumbent did not run for reelection at the end of a term (or resigned during it) and became a registered lobbyist in the year of leaving office or the one thereafter. There is a negative treatment effect for all legislators, and it is again larger for Republicans than for Democrats. The magnitudes of the effects are very similar to the ones in Table 2.

Table 3. Treatment effect β of Citizens United on the probability that a legislator will leave office and register as a state lobbyist after voluntarily leaving office or after losing reelection.

*p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01. Regressions include state-level and individual-level controls, state and year fixed effects, and state-specific time trends. Robust standard errors clustered by state in parentheses.

The other three models in Table 3 analyze the insurance revolving door. The dependent variable takes the value of one if the incumbent ran for reelection at the end of a term and became a registered lobbyist the same year or the year after losing their seat. Citizens United had no effect on the propensity of politicians to become lobbyists after failing to win reelection, neither among Republicans nor among Democrats.

The Supreme Court ruling thus only led to a decrease in the number of politicians who voluntarily and consciously left office and then became lobbyists. This provides support for the argument that less restrictive campaign finance regulation leads to a deliberate decision by incumbents to use the opportunity to benefit from special interest money by enhancing their chances to stay in office rather than through a revolving door job that improves their personal financial situation.

5.3. No Effect on Retirement Not Followed by Revolving Door Employment

Besides heterogeneity between parties in how much a loosening of campaign finance rules affects revolving door employment, there should also be individual differences. In particular, some incumbents are more important for special interests than others. The former benefit from campaign money and are often later employed as lobbyists. The latter benefit less from campaign spending and are also less likely to go through the revolving door. The empirical implication of this is that we should not see a negative effect of Citizens United on the probability that legislators leave office without going through the revolving door.

Table 4 shows the effect of Citizens United on a dependent variable that takes the value of one if a legislator voluntarily leaves office and does not register as a lobbyist in the year of leaving office or the one thereafter. The point estimate for the pooled sample is positive and far from statistical significance. The Supreme Court ruling thus did not have an effect on the career paths of politicians who would not go through the revolving door upon exiting office. This suggests that the looser campaign spending laws did not benefit them in a significant manner.

Table 4. Treatment effect β of Citizens United on the probability that a legislator will leave office but not register as a state lobbyist.

*p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01. Regressions include state-level and individual-level controls, state and year fixed effects, and state-specific time trends. Robust standard errors clustered by state in parentheses.

The finding becomes even clearer when breaking it up by party. The second column in Table 4 shows that while the treatment effect for Republican incumbents is negative, it is nowhere near conventional levels of significance.Footnote 14 Thus even among Republicans, who overall benefited to a greater extent from the increased independent campaign spending than Democrats, many legislators apparently did not expect enough of a shift of their electoral fortunes to warrant a change in their career paths.

Finally, the last column of Table 4 shows that the treatment effect of Citizens United on Democrats was positive and significant at the 10 percent level. A good share of Democratic incumbents seem to have anticipated that the looser campaign finance laws would disadvantage them, that is, lower their P, consistent with the argument that they themselves were not enough on the radar of moneyed special interests to benefit from greater spending. And given the overall partisan imbalance in spending increases, they were also more likely to run against a well-financed Republican (cf. Klumpp et al., Reference Klumpp, Mialon and Williams2016; Abdul-Razzak et al., Reference Abdul-Razzak, Prato and Wolton2018; Petrova et al., Reference Petrova, Simonov and Snyder2019). In response, Democratic incumbents were more prone to voluntarily leave office without going through the revolving door.

In summary, the Supreme Court ruling had heterogeneous effects between as well as within the parties. It affected Republicans more than Democrats, and the ruling only had an impact on legislators who were to go through the revolving door, but did not affect those who were to simply retire.

5.4. Robustness Checks

To ensure the robustness of the results I conduct extensive additional analyses, which are discussed in the Online Appendix. They include permutation tests; models using alternative coding decisions for the treatment variable; separate estimations for states with and without cooling off laws; and estimations using the full sample of legislators rather than just those at the end of their term. All findings are robust to these alternative specifications. As a placebo test, I also show that Citizens United had no effect on the career decisions of term-limited legislators. Finally, I present all analyses for the upper chambers. Consistent with research showing that the ruling had no effect on their election outcomes (Klumpp et al., Reference Klumpp, Mialon and Williams2016), I find no impact on the career decisions of senators.

6. No Effect on Overall Demand for Lobbyists

I have argued that the drop in revolving door employment following Citizens United can be attributed to a change in the supply of politicians willing to leave office and take up a lobbyist job. However, special interests may also have decided that in this new electoral environment, they are less in need of lobbyists that communicate their policy preferences. The drop in revolving door employment could thus be the result of a change in demand. If this is true, we should see that Citizens United not only had a negative effect on the number of revolving door lobbyists, but also on the number of lobbyists overall.

To test this, I estimate difference-in-differences regressions of the ruling's effect on lobbying efforts in state legislatures. I use three different dependent variables: the logged number of lobbyists registered in state s in year t, the logged number of clients who hired a lobbyist in a given state and year; and the logged number of unique lobbyist-client pairs.Footnote 15 The state-level controls are the same as in the models above.

Table 5 shows that there is no evidence that the less restrictive campaign finance rules affected the demand for lobbyists. While the point estimates for all three variables are negative, they are far from statistical significance. This supports the argument that the change in the prevalence of revolving door employment was the consequence of a change in the supply of politicians willing to leave office to represent special interests.

Table 5. Treatment effect β of Citizens United on the log number of lobbyists, clients, and lobbyist-clients.

Regressions include state-level controls, state and year fixed effects, and state-specific time trends. Robust standard errors clustered by state in parentheses.

7. Conclusion

For the revolving door to spin, there need to be employers who hire former politicians, and politicians need to be willing to leave electoral politics behind them. The existing literature focuses almost exclusively on the demand-side. In this paper, I have demonstrated the importance of the supply-side using a change to the institutional environment that was exogenous to legislators. More permissive campaign finance rules led to a drop in politicians voluntarily leaving office to go through the revolving door. The effect was more pronounced among politicians that are likely to benefit from special interest spending to a greater degree.

This paper represents a first step in the examination of the supply-side of the revolving door. As such, it raises many open questions for future research. One concerns the overall impact of campaign finance reform on the influence of moneyed interests. The prevailing notion is that more permissive campaign finance laws lead to an increase in special interest spending and influence. However, I have shown here that the growth in campaign spending causes a countervailing decrease in the revolving door. Is the net effect on the influence of special interests positive, negative, or neutral?

Another open question is whether the shift from revolving door employment to election spending induced by changes to campaign finance legislation affects the distribution of power among special interests. Do the same organizations that employed revolving door lobbyists now spend more on campaigns? Or does the additional campaign spending come from elsewhere, crowding out groups that used to hire former legislators? There is some evidence that the latter was true in the case of Citizens United (Hansen et al., Reference Hansen, Rocca and Ortiz2015), but the lack of transparency for independent campaign expenditures (Hamm et al., Reference Hamm, Malbin, Kettler and Glavin2014) means a systematic study is difficult. Future research could instead analyze the effect of state-level changes that regulate direct, and therefore disclosed, campaign contributions on the revolving door.

More broadly, Figure 1 has shown a lot of variation between states, much of which remains unexplained. The simple cost-benefit analysis laid out in Equation 1 can serve as a guide for further study. In addition to cross-state differences within the United States, there also is cross-national variation in the revolving door to be explained. This means that the literature has to place greater emphasis on taking a comparative approach.

Finally, the fact that spending on campaigns and spending on the revolving door are related raises questions about the connection between different forms of money in politics. Most existing work focuses on a single type, such as campaign contributions (or specific forms thereof), self-enrichment, or the revolving door. Some recent contributions on the endogenous choice between different venues of special interest influence have already hinted that this silo mentality likely leads to an understanding that at best is incomplete (e.g., Campos and Giovannoni, Reference Campos and Giovannoni2007; Nyblade and Reed, Reference Nyblade and Reed2008; Harstad and Svensson, Reference Harstad and Svensson2011; You, Reference You2017). The findings in this paper corroborate this notion. In the future, it will be necessary to draw together the disparate literatures on different forms of money in politics, and to study how they interact with each other. This move from a partial towards a general equilibrium view of money in politics will help us better understand and anticipate what so far have been unintended second-order consequences.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2019.46

Acknowledgments

For their comments and suggestions, I am thankful to Ben Barber, Pablo Beramendi, Pablo Fernández-Vázquez, Daniel Gingerich, Florian Hollenbach, Jan Pierskalla, Karen Remmer, Luis Schiumerini, Alberto Simpser, Danielle Thomsen, Michael Ward, Erik Wibbels, Hye Young You, as well as the PSRM editor Paul Kellstedt and the anonymous reviewers.