Because of the importance of party, considerable attention must be devoted to the way in which the party as an organization intrudes on the relationship between representative and represented – S. H. (Barnes, Reference Barnes1977, 135).

As the above quote shows, several political science classics consider party organization as a key determinant of the failure or success of democratic representation (Ostrogorski, Reference Ostrogorski1902; Michels, Reference Michels1915; Weber, Reference Weber2004). If we conceptualize the quality of representation as the level of congruence between the policy positions of the party and its voters, then the so-called mass party is often portrayed as an organization best able to achieve this congruence (Duverger, Reference Duverger1964; Lawson, Reference Lawson1980; Rohrschneider and Whitefield, Reference Rohrschneider and Whitefield2012; Mair, Reference Mair2013). In particular, organizational features such as a large, committed and homogeneous membership and an intensive and democratic international structure contribute to achieving congruence. But developments such as increased leadership-domination (Michels, Reference Michels1915), adoption of catch-all strategies (Kirchheimer, Reference Kirchheimer, LaPalombara and Weiner1966) and the integration of parties into the state (Katz and Mair, Reference Katz and Mair1995) all point towards a decrease in the quality of representation (i.e., a decrease in congruence). Also, many parties never were mass parties, and their organizations look more like other ideal typical parties such as the elite party, the cartel party or the catch-all party (Katz and Mair, Reference Katz and Mair1995).

In fact, we know very little about the effect of party organization on congruence between parties and voters. This is because most contemporary studies explain variation in representation with differences in the electoral system (e.g., Huber and Powell, Reference Huber and Powell1994; Golder and Stramski, Reference Golder and Stramski2010). Despite calls that there is more variation between parties in terms of congruence than between countries (Holmberg, Reference Holmberg and Miller W.1999; Wessels, Reference Wessels and Miller W.1999), only a few studies analyze this. Rohrschneider and Whitefield (Reference Rohrschneider and Whitefield2012) find that traditional features of mass party organization increase congruence in Western Europe. But Dalton (Reference Dalton1985) reports no differences between mass and non-mass parties, instead he shows a positive effect of centralization of candidate selection (also see Spies and Kaiser, Reference Spies and Kaiser2014), a factor Rohrschneider and Whitefield did not consider. What explains these divergent expectations and findings regarding the effect of party organization on congruence?

The study of congruence between political actors and their constituents has a long tradition in the political science literature and is seen as normatively important (e.g., Dalton, Reference Dalton1985; Belchior, Reference Belchior2013). Substantive representation, that is, a link based on ideology or specific policy issues, is guiding this literature—either explicitly or implicitly—because it touches the core of the concept of representation: democracy should ensure that the representatives reflect the ideological preferences of its citizenry (e.g., Thomassen, Reference Thomassen, Jennings M. and Mann T.1994). Importantly, empirical research suggests that substantive representation or in other words close congruence is valued highly by citizens as well (see e.g., Bengtsson and Wass, Reference Bengtsson and Wass2011). In this contribution, we focus on a central aspect of representation: the linkage between political parties and their voters (see also Dalton, Reference Dalton1985; Thomassen, Reference Thomassen, Jennings M. and Mann T.1994; Adams and Ezrow, Reference Adams and Ezrow2009). Party-voter congruence is an important pre-condition for government-citizen congruence. Itis also valuable by itself as citizens' ideological or policy preferences are represented by political parties and only the party system “makes it possible for citizens to express their preferences” (Powell Jr, Reference Powell2004, 93).

The literature on political parties offers several perspectives that suggest different ways in which parties establish congruence with voters. For our purpose, we discuss two of them. (1) Parties are information channels and function as intermediaries between public opinion and public policy (Duverger, Reference Duverger1964; Epstein, Reference Epstein1967; Katz and Mair, Reference Katz and Mair1995). As such, congruence is a bottom-up process with parties following and transmitting (changes in) public opinion (Downs, Reference Downs1957; Krehbiel, Reference Krehbiel1988; Adams et al., Reference Adams, Merrill and Grofman2005). The function of the party organization is primarily delivering information about the electorate. (2) Parties are institutions that integrate individuals into politics and provide salient social identities. They motivate people to vote, but more importantly, parties provide training, indoctrination and a network that integrate members into political life and groom the ambitious ones into office-holders (Duverger, Reference Duverger1964; Weber, Reference Weber2004). From this perspective, congruence is a top-down process. Voters who strongly identify with a party (Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Converse, Miller and Stokes1960) or a party leader (Lenz, Reference Lenz2012) follow the party if it changes position. Here either the parties' abilities to socialize, integrate and indoctrinate individuals is of central importance or the party leaders' abilities to engage individuals and sway voters with his or her charismatic performance.

Party organizations vary in the degree to which they can make use of these two mechanisms to achieve party-voter congruence. We analyze two key characteristics on which party organizations vary: (1) horizontal integration—the degree to which a party has a significant party membership and (2) vertical integration—the degree to which the leadership or the party members dominate the party (Panebianco, Reference Panebianco1988; Kitschelt, Reference Kitschelt1994). We develop hypotheses regarding the effects of horizontal and vertical integration by building on the existing literature and further developing some of its implications. By doing so, we surprisingly find arguments that posit either a positive or a negative association with congruence for horizontal and vertical integration. To move beyond this unsatisfactory state of art, we classify the arguments as being either about the uncertainty or the bias in the signal of the party electorates that party officials receive. This framework allows getting closer at the mechanism driving close or weak party congruence and thus advancing the theory substantively. We conceive the broad concept of “political representation” as ideological congruence and measure the concept as the actual distance on a left-right scale between representatives and represented, that is, the party position and the current party electorate. We provide several congruence measure that help us disentangling the mechanisms of either information or identification and bottom-up versus top-down paths of congruence formation. The former is captured with a congruence measures focusing on objective party positions while the latter takes into account the subjective positioning of parties by individuals. For the analysis we constructed a party level data set using the Comparative Studies of Electoral Systems (CSES) data with 14 countries and 196 cases included.

1. Developing hypotheses

1.1. Two characteristics of party organizations

We consider two characteristics of party organization: a first dimension which we coin “horizontal integration” concerns the “party on the ground” (Katz and Mair, Reference Katz and Mair1993), that is, the size of its membership base and the organizational differentiation of the party. Here, we differentiate between parties that put a lot of emphasis on their members, which cultivate mass membership and maintain a geographically fine-grained organizational structure on the one hand, that is, for which membership is significant, and a party that does not count on members or does not even embrace formal membership and exists basically only as “party in public office” (Katz and Mair, Reference Katz and Mair1993). However, that parties have large memberships does not mean that the members have much to say about party policy. This is captured by our second dimension, which we label “vertical integration”. This measures leadership domination within political parties (see e.g., Panebianco, Reference Panebianco1988; Kitschelt, Reference Kitschelt1994). According to Panebianco (Reference Panebianco1988) party leaders differ in their degree of freedom of choice. In some parties leaders effectively decide on all aspects of party policy (candidate selection, platform construction, goal definition). In other parties the rank-and-file, mid-level activists, trade unions or other potential veto players inhibit the leadership or even effectively decide on party policy. Schumacher et al. (Reference Schumacher, De Vries and Vis2013) conceptualize this as a scale, with on one side parties that are leadership-dominated and on the other side parties that are activist-dominated.

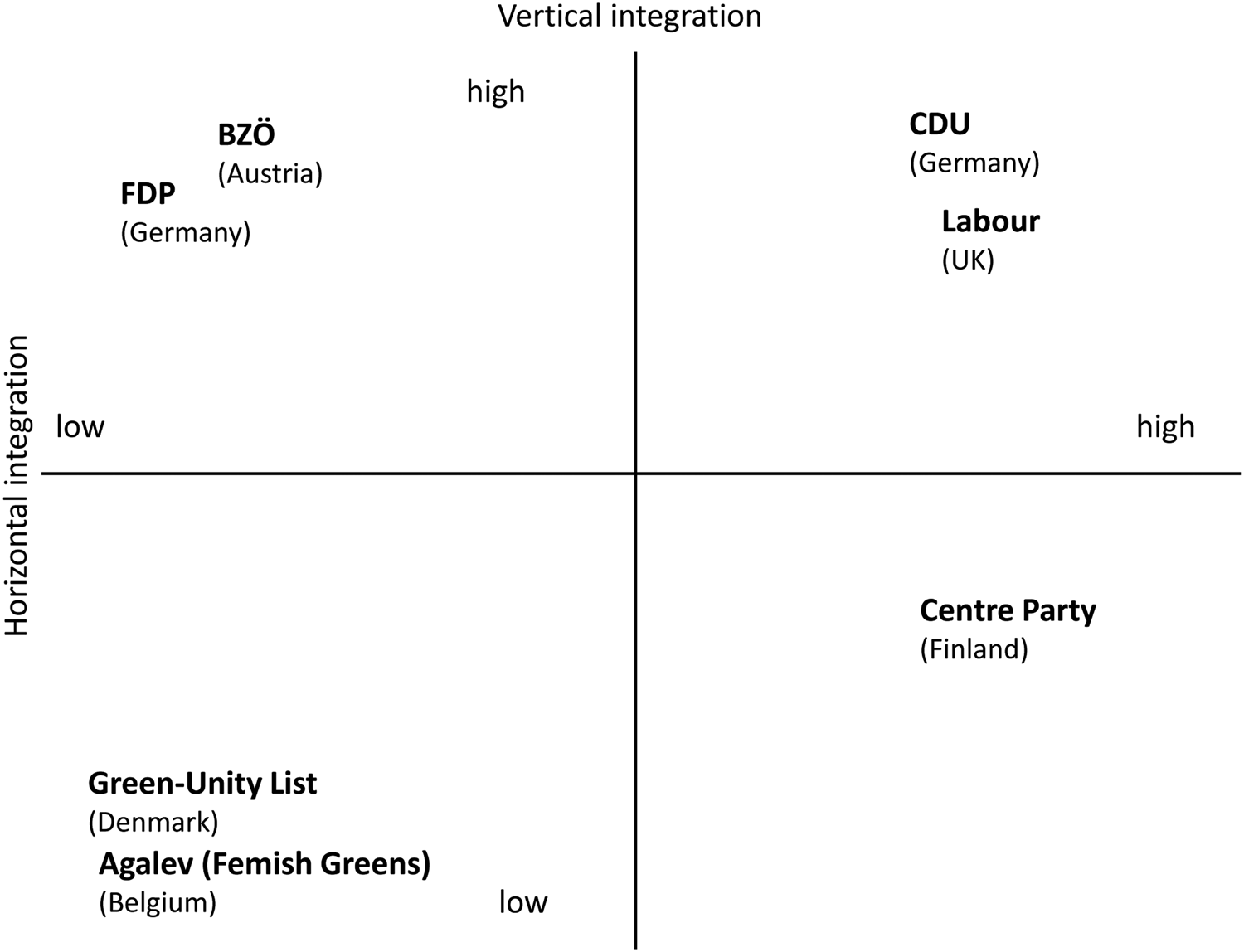

Figure 1 previews these two dimensions of internal party organization; the exact operationalization is discussed in Section 2. The point here is to give examples and demonstrate that the two dimensions are conceptually and empirically independent.Footnote 1 In the top right corner we find parties that combine a mass membership organization with a strong position of the party leader. Examples include the German Christian Democrats (CDU) but also Labour in the UK. In the top left corner, parties without mass membership but again a high concentration of power are located. Here we find younger populist parties such as the BZÖ (Bündnis für Österreich) in Austria but also established parties such as the German liberals (FDP). Turning to the lower part of the figure and thus to parties that have a low degree of leader power, we find in the left lower corner predominantly Green parties which combine weak hierarchies with low membership organization. The final corner of the figure (lower right) features parties that have a low concentration of power but a highly horizontally integrated party organization. An example for this combination is the Centre Party in Finland.

Figure 1. Two dimensions of party organization—an empirical illustration. Note: A version of this figure including all parties in the sample is available in the Supplementary Information.

With our emphasis on these two party organizational characteristics we ignore other aspects of party organizations, for example, the strength of the party apparatus (Pedersen, Reference Pedersen2010; Rohrschneider and Whitefield, Reference Rohrschneider and Whitefield2012), the relationship between (national and sub national) party branches (Thorlakson, Reference Thorlakson2009; Bolleyer, Reference Bolleyer2012; Spies and Kaiser, Reference Spies and Kaiser2014) and party finance (Scarrow, Reference Scarrow2007). Partly, these aspects should be integrated or closely related to the two characteristics in Figure 1. Still, we do not exclude the possibility that they have an independent effect as well. Some studies have taken the formal centralization of candidate or leadership selection (Spies and Kaiser, Reference Spies and Kaiser2014; Cross and Pilet, Reference Cross and Pilet2015) as explanatory variable of inter-party differences in party-voter congruence. These formal rules are used as proxies for the distribution of power within a party. However, formal rules may not describe actual intra-party decision-making processes well. In fact Schumacher and Giger (Reference Schumacher and Giger2017) find only weak correspondence between formal rules of leadership selection and leadership domination. A change in formal rules such as democratization of leadership selection procedures is associated with more leadership-domination (Mair, Reference Mair, Katz R. and Mair1994; Scarrow, Reference Scarrow, Dalton R. and Wattenberg2002) even though it is supposed to distribute power away from the leadership. Also, formal selection rules vary little, and are sometimes determined by law. By consequence, the German Greens should for example be considered as equally leadership-dominated as the German Christian Democrats. This does not match with case study evidence on these parties (see e.g., Kitschelt, Reference Kitschelt1988).

1.2. Party-level congruence

For congruence to be established it takes two actors: political parties, their organization respectively, and the electorate of these parties. Close congruence as the end product of the process is achieved if both actors are positioned closely together. In essence, ideological congruence is thus a static concept that allows for nothing more than an “inventory” of the state of representation without much a priori insights into the mechanisms that generate the alignment. However, by which mechanism congruence is achieved is of crucial relevance for our understanding of the interplay between parties and their constituents. It is our aim to generate insights into the mechanisms that create weak or strong congruence.

We take the party as our departure point. From there, two perspectives can be separated. A first sees party organizations primarily as information channels that facilitate the extraction of relevant policy information about the electorate. As such, congruence is a bottom-up process. A second perspective views parties as identification vehicles that allow individuals to integrate into politics and as such congruence is a top-down process. The specifics of party organization are crucial in both perspectives and we thus develop hypotheses which argue that on the one hand variation in the horizontal integration of parties explains the degree to which parties can extract information about the electorate from their membership. On the other hand, the degree of horizontal integration may facilitate or hinder the identification of members and voters with the party. Vertical integration moderates the incentives of party leaders, and thereby influences how the information and identification mechanisms are employed. Like horizontal integration, vertical integration may have a positive or a negative effect on party congruence. We argue that horizontal integration and vertical integration affect the uncertainty of the estimate of the party electorate's position. At the same time, these party organization characteristics can also produce biased signals from members to party officials, because only a subsection of all members make themselves heard. We will now develop our hypotheses structured along the lines of the two party functions (information versus identification) and according to the distinction between arguments about uncertainty versus bias in the estimate of the electorates' position.

1.3. Horizontal integration

If we assume a bottom-up model of congruence in which parties maximize vote share by choosing popular policy positions, then parties should invest in receiving correct signals about the preferences of the electorate. Party organizations can channel information about public opinion to the leader. If a party has few members, there is much uncertainty about the position of the party's electorate. However, the more members, the more this uncertainty is reduced. Even if members hold positions different from the larger group of party voters, at least with more members there is more certainty about their position. From this party leaders can take cues regarding where they should move in a policy space to optimize their electoral pay-offs. This will increase congruence between the party and its voters. If, however, the leader is uncertain about the position of the members, because there are only a few of them, then she is less likely to achieve congruence. This can be because relevant trends in public opinion are missed, or simply because the wrong position was chosen. In all this suggests that membership size reduces uncertainty and therefore is more likely to produce congruence (H1a).

Assuming a top-down process of congruence, with voters following the leader rather than the other way around, the function of parties is rather different. The goal is not to persuade voters, but to create a followership that adjusts its opinions to the party's position. In other words, what matters from this perspective is the party's ability to integrate voters into the party either as a member or a sympathizer. By organizing activities and offering political schooling parties socialize members and produce pliable followers. These can be used as inexpensive labor during election campaigns. Also, they provide a loyal vote base, directly through their own vote and indirectly by the networks these members bring with them. Because they identify with the party, they are also more likely to claim their ideology is congruent with the party. This way, a party with a sizable party membership can be expected to have congruent policy positions with its voters (H1a). This is not because the party strategically chose that position, but because a sizable portion of the party's voters are sufficiently integrated to indicate that they have the same policy position as the party. Similar to the bottom-up view, party membership size reduces the uncertainty of the position of party voters. But now congruence is the product of party identification. Even though party membership has much declined (Van Biezen et al., Reference Van Biezen, Mair and Poguntke2012), variation between parties remains (Kölln and Polk, Reference Kölln and Polk2017) and therefore it is still plausible that the hypothesized effect is observed.

Hypothesis 1a Horizontal integration is positively linked to party congruence.

The critical assumption in the bottom-up view of the previous section is whether party members are an unbiased sample of party voters and whether the channels through which party elites receive information are unbiased. Within parties only a “zealous minority” (Dalton, Reference Dalton1985, 289) makes itself heard. If the opinions of this minority are not representative of the average member or voter, overall congruence plummets. In fact, the Law of Curvilinear Disparity (May, Reference May1973) argues that the group of sub-leaders will hold the most extreme positions within a party, positions that are neither shared by the non-leaders nor the leaders who both are assumed to have more moderate views. If we assume May's sub-leaders make up this “zealous minority” party elites will receive biased signals about public opinion from its organization. With a large party membership, the leader is more certain about its position, however, that position itself is unrepresentative of the party's electorate.

Following the top-down argument again, size also influences identification. The larger a group, the more apathy among its members (Olson, Reference Olson1965). Indeed, membership participation in party activities declines as party size increases (Scarrow, Reference Scarrow, Dalton R. and Wattenberg2002; Weldon, Reference Weldon2006) and probably makes it more likely that zealots are heard instead of ordinary members. Thus, larger parties may suffer from more biased information regarding public opinion. Also, because apathy increases with size, identification with the party and its policy position may be weaker, even among members and supporters. For example, the Swedish Social Democrats—the largest party in Sweden in terms of membership—has by far the highest level of incongruence with its members (Kölln and Polk, Reference Kölln and Polk2017). In sum, because of biased information and suppressed identification other literatures suggest the hypothesis that membership size has a negative effect on congruence (H1b).

Hypothesis 1b Horizontal integration is negatively linked to party congruence.

1.4. Vertical integration

In a bottom-up perspective, Müller and Strøm (Reference Müller and Strøm1999, 17) argue that the “more leaders decentralize policy decision making, the more policy oriented the party is likely to become at the expense of office- and vote-seeking.” Party organization researchers have extensively reported examples of this (e.g., Wolinetz, Reference Wolinetz1993; Kitschelt, Reference Kitschelt1994; Seyd, Reference Seyd1999; Egle and Henkes, Reference Egle, Henkes, Haseler and Meyer2004). In most of these instances office-seeking strategies of the party leadership were vetoed to the benefit of a policy-pure strategy supported by the membership. Leadership-domination is evidently an important variable here. The more activists have a say over party policy, the more opportunities they have to defend policy purity at the expense of other strategies (Schumacher et al., Reference Schumacher, De Vries and Vis2013). The less activists have a say over party policy, the more the agenda will be set by the party leader. If the core motivation of party leaders is office-seeking, we can assume that he or she chooses policy positions that maximize the probability of obtaining that goal. Winning elections is—also in multi-party systems (Mattila and Raunio, Reference Mattila and Raunio2004)—one road to office, and to do so a leader should choose a position where the average voter is. This should reduce bias. The “zealous minority” from the previous section is simply less influential, that is, has fewer opportunities to exercise veto or amendment rights, and therefore is heard less in parties that are leadership-dominated than in parties that are not. This lifts the potential bias effect and should increase congruence (H2a) (Dalton, Reference Dalton1985). Following this some even say that a hierarchically organized and highly centralized structure serves as prerequisite of the responsible party model (Epstein, Reference Epstein1967; Harmel and Janda, Reference Harmel and Janda1982).

The top-down view produces another reason to expect higher congruence in parties that are leader-dominated. This is because a single dominant leader may be more effective in triggering individuals to identify with the party. For example, the congruency model of political preference predicts that voters support politicians similar to their own personality. Successful politicians thus “speak the language of personality (…) by identifying and conveying those individual characteristics that are most appealing (…) to a particular constituency” (Caprara and Zimbardo, Reference Caprara and Zimbardo2004, 581). In leadership-dominated parties it is easier for voter to identify the leader, the leader is less restrained and there are fewer obvious contenders for the leadership. Therefore leaders in leadership-dominated parties may perform better in striking a personal relationship with voters than leaders who are less in control of their party. With this strong personal relationship a voter is more likely to perceive the party's position to be congruent with his or her own position. At the same time, with a good number of members strongly identifying with the leader, the role of a “zealous minority” is much more limited, because the majority of the party is zealous in defending the leader. In parties with weak leaders, and strong activists, the identification of members with the leader is likely to be weaker, and therefore the members are less likely to defend the leader against the “zealous minority.” In that situation, the bias in the position of the membership emerges, whereas it is suppressed if the leader is dominant in the party. This suggest a positive effect of leadership-domination on congruence (H2a).

Hypothesis 2a Vertical integration is positively linked to party congruence.

Following a bottom-up perspective, we assumed previously that leader-dominated parties pursue office pay-offs more directly than activist-dominated parties. By consequence, they achieve higher congruence. Yet, this is not necessarily the outcome. Schumacher et al. (Reference Schumacher, De Vries and Vis2013) find that leader-dominated parties are more likely to follow policy shifts of the median voter, whereas activist-dominated parties are more likely to follow the policy shifts of the median party voter. This means that leader-dominated parties in fact move more out of sync with their party voter than activist-dominated parties. In other words, and somewhat paradoxically, pursuing vote and office goals, parties produce weaker congruence with their own voters (H2b).

From a top-down perspective we can also turn around the argument about a positive relation between leadership domination and congruence. Parties with more leadership-domination change their policy platform more drastically than parties with less leadership domination (Schumacher et al., Reference Schumacher, van de Wardt, Vis and Klitgaard2015). Some voters may reward ideological rigidity and will therefore closely identify with that party. Because leadership-domination depresses ideological rigidity, one can also expect a negative effect of leadership-domination on congruence. Also, what is the psychological effect of being a leader? Party leaders constantly receive confirmations of their power, the more so if they are dominating their party and have no fear of being unseated or criticized by party members. Experiments demonstrate that individuals primed with power are more likely to be greedy (Rucker et al., Reference Rucker, Dubois and Galinsky2011), less aware of other people (Muscatell et al., Reference Muscatell, Morelli, Falk, Way, Pfeifer, Galinsky, Lieberman, Dapretto and Eisenberger2012), more overconfident and hypocritical (Lammers et al., Reference Lammers, Stapel and Galinsky2010) and in sum become rather intolerable individuals. Assuming that receiving power primes can serve as an experimental analog to actual leader behavior, we can expect that leaders will fail to motivate followers because their behavior is no longer representative for the group and seems out of tune with group interests (Haslam et al., Reference Haslam, Reicher and Platow2011). Reversely, if leaders are forced to share responsibilities for party policies they receive fewer or weaker power primes. By consequence, these leaders are less likely to become estranged from the rest of the party. Following these arguments it is to be expected that leadership domination has a negative effect on congruence, because voters are unwilling to closely identify with the party (2b).

Hypothesis 2b Vertical integration is negatively linked to party congruence.

We summarize our main expectations in Table 1.

Table 1. Summary of hypotheses and arguments

BU: bottom-up perspective, TD: top-down perspective.

Do we expect horizontal and vertical integration to jointly influence congruence? H1a does imply that party leaders indeed take the median position of their party supporters as position. There are some suggestions that the degree of leadership domination in a party may either facilitate or obstruct the degree to which party leaders take the median position of party supporters. Introducing primaries to select a party leader is often seen as a measure of forcing the leader to take the median position (Meirowitz, Reference Meirowitz2005; Adams et al., Reference Adams, Haupt and Stoll2009) and thus the combination of horizontal integration and vertical integration should jointly predict better congruence between the party and its voters. However, it is doubtful whether primaries have this effect because valence aspects of candidates seem more important than ideological aspects (Adams et al., Reference Adams, Haupt and Stoll2009; Serra, Reference Serra2011) and therefore parties that introduce primaries do not become less leader dominated (Schumacher and Giger, Reference Schumacher and Giger2017). Also, low vertical integration is unlikely to lead to parties' taking the median position of their supporters. Parties in which activists were relatively powerful (e.g., left parties in the 1980s such as Dutch and British Labour) did not have intra-party democracy, but had relatively small and influential party councils filled with party militants instrumental in the radicalization of these parties as well as the resistance against moderation (e.g., Schumacher, Reference Schumacher2012). In these cases, activists managed to push the party away from the median of its supporters and suppressed more moderate supporters' influence. In essence, these arguments can be read as predominantly speaking against a close connection between the horizontal and vertical integration axes (see also Footnote 1).

2. Data and methods

In this study we rely on a sample of 79 parties from 14 West European countriesFootnote 2 and 37 elections. Our sample spans the time framefrom 1998 to 2013. In essence, our sample is restricted by the availability of individual level election study data and corresponding party organization information.

We conceive congruence as ideological congruence. In particular, we follow the state-of-the-art as defined by Golder and Stramski (Reference Golder and Stramski2010). We are especially inspired by the concept of relative congruence which controls for the dispersion of citizens attitudes. We believe such a measure net of voters' dispersion is particularly suitable for the context of party level congruence as the differences in constituency dispersion are presumably high and as a consequence adapted this measure for the party level. In this measure C i indicates the party voters' position while MV p denotes the position of the median voter of a party and P is the position of the party.

Relative congruence

To get closer at the mechanisms that generate the observed level of relative congruence, we look at four other measures of linkage between voters and parties. First, we are interested in the distinction between bottom-up and top-down perspectives on congruence. The bottom-up perspective relies on an information argument and sees political parties primarily as information channels while the top-down perspective focuses on the integration aspect of political parties. In essence, the difference boils down to looking at congruence from an individual, citizens point of view versus a more systemic, objective approach. We thus look at subjective congruence which we operationalize as the individual distance of each individuals position (C i) to his or her preferred party position (P i):

Subjective congruence

The objective congruence measure is what has been coined absolute congruence before (Golder and Stramski, Reference Golder and Stramski2010) and simply compares an aggregate-level, objective party position to the dispersion of its constituency:

Objective congruence

Second, we utilize two measures to capture the concepts of “uncertainty (standard error)” versus “bias” in estimates of party electorates directly. We thus calculate the standard error in the distribution of left-right positions of partisans (standard error) and the distance between the party position and the median of citizens' position to capture the bias. Important, to facilitate interpretation, for all dependent variables higher values indicate better congruence.

Our dataset is a combination of individual level mass surveys and party level information. From the CSES dataset we infer information on the ideological positioning of party voters (left-right scale). While not without problems, scholars agree that the left-right dimension captures the ideological position of citizens and parties reasonably well (Holmberg, Reference Holmberg and Miller W.1999; Powell Jr, Reference Powell2004). In addition to the left-right placement of individual voters we extract party positions on thesame left-right scale also from the CSES data. Our measure of party positions is the average perceived position of voters in the CSES data. This procedures carries the advantage that both measures are in the same political space and thus easier to compare and that the measures are time-variant (see Golder and Stramski, Reference Golder and Stramski2010 for a similar approach).Footnote 3 As a last piece of information we code the vote choice in order to match it with party information. Congruence scores are then calculated in the fashion outlined above.

At the party level we combine two data sources: information on party organization comes from Rohrschneider and Whitefield (Reference Rohrschneider and Whitefield2012)Footnote 4 where we use a question about whether the party has a “significant” membership base in terms of members' to get at horizontal integration.Footnote 5 Vertical integration is measured by questions which ask about the policy determining capacities of various of three party branches (party membership, party apparatus, party leadership). We code the difference between the values of the “party leadership” variable minus the capacities of the “party membership” as indicating leadership-domination.

Our models include a number of controls. It is vital to control for government participation as being a member of the cabinet could alter the linkages to the party's constituents. At least in theory, parties in government must recognize and represent other interests in society than simply their party voters (Rohrschneider and Whitefield, Reference Rohrschneider and Whitefield2012). Also, office comes with more chances to communicate your policy positions and thus these parties might be better in attracting “fitting” voters. Opposition parties in contrast have the freedom to take policy positions without bearing the consequences. In addition, long-term government participation can beseen asan indicator for good representation as these parties enjoy the trust of their voters (Dalton, Reference Dalton1985). In a similar vain, we also include a control for vote share as larger parties can be seen as more successful and thus potentially more congruent and also larger parties could have a different ratio of members to voters which potentially impacts their congruence with their voter base. Further, we identify niche parties as they could be advantaged in representing their constituencies. We employ the approach by Somer-Topcu (Reference Somer-Topcu2015) to identify niche parties as single-issue parties (less than the mean minus one standard deviation of the manifesto dedicated to left-right issues). Our final control year of foundation taps into earlier research which shows that older parties are more representative (e.g., Dalton, Reference Dalton1985). All information is coded from Schumacher and Giger (Reference Schumacher and Giger2017).

We estimate multilevel linear regressions to capture the hierarchical structure of the data. For the models shown in this study, we operationalize countries as the second higher level but the results are stable if we take elections instead.Footnote 6

3. Empirical findings

We begin the empirical results section by looking at the variance distribution of the dependent variable between party and country level. A so called “empty” linear multilevel regression model allows estimating how much variance of the dependent variable is located at the various levels of analysis (full modelis given in Supplementary Information). For relative congruence, our main dependent variable, it shows that at the party level about 94 percent of the total variance is situated while the country level is only responsible for around 6 percent of total variance. This substantiates our claim that looking at the party level to explain variation in congruence is promising.

This initial result calls for explanations that are located exactly at the party level. This is what we turn to next. Table 2 provides the results for relative congruence. This measure best captures the concept of party congruence as it emphasizes the optimal position taking of parties vis-à-vis their constituents irrespective of how widespread the voters' distribution is. In the two first models we introduce our two measure of horizontal and vertical party organization separately while the third models features both variables simultaneously. Our results indicate a consistent negative effect of mass membership and a slightly less robust influence of leadership domination on relative congruence. So, parties which rely more heavily on a mass membership structure are less successful in representing their voters. The same applies at least in the tendency to parties dominated by a leader. In other words, large mass membership and high leadership domination are associated with lower levels of congruence. The results therefore corroborate hypotheses 1b and 2b and are stable.Footnote 7 The effects of party organizational measures are not only statistically significant but also substantively important. For relative congruence for example, moving from the minimum to the maximum of our measures means about a standard deviation change of the dependent variable which can be considered sizable changes.

Table 2. Explaining relative congruence

Next we turn to getting closer at the mechanisms that produce these effects. We first set out to get a grip on whether the link between our party organization measures and congruence is due to a information (bottom-up) or identification (top-down) mechanism. If it is the first, we should see the influence of party organization more strongly in models with objective congruence as this captures how parties objectively position themselves vis-à-vis their electorate. If it is the latter, the influence should be stronger for subjective congruence. Here, we capture how individuals see their party being close to them and thus more the identification dimension of congruence. The corresponding results are shown in Table 3, Models 1 and 2. They suggest that the influence of leadership domination works primarily through an identification mechanism. For the negative influence of mass membership the situation is less clear as both models produce coefficients that are equally significant. Given that in Model 1 (objective congruence) the influence of mass membership is rather weak (p = 0.45) (and does disappear in some robustness tests, for example, with party positions estimated from educated respondents only), we would still lean toward an information argument as main explanation.

Table 3. Explaining the mechanisms

In sum, these findings suggest that while we find strong support for the arguments about larger membership bases leading to apathy (H1b, top-down argument) and tentative support for the argument large size producing more biased information on voters preference, for leadership domination the situation is more clear. Here, mainly the arguments about leaders enforcing office-maximizing positions to the detriment of voters (H2b, bottom-up argument) are supported by our data although the data suggest also a psychological, identification path in the sense of a dominant leader to become estranged to have some influence.

Last, we look at substantiating our initial results in favor of H1b and H2b, that is, the negative influence of large membership bases and strong leadership domination. The finding regarding horizontal integration is based on arguments stressing the potential bias in the estimate of party constituency measures, in other words it is about biases in the information that party officials receive from their electorate. We provide additional face-validity for this pathway with a more tailored measure for this biased signal argument: the distance between the party position and the median party electorate. This measure directly compares the two positions and thus gives us a straight-forward measure of the distance, that is, bias, between them.

Table 3, Model 3 provides the corresponding analysis. The effect of mass membership on absolute distance (β = 0.77) demonstrates that the positions of mass membership parties are on average further away from their voters. The fact that these parties do not align more closely with their voters, is, in our view, due to the fact that these parties have received and responded to biased signals about the position of their voters. This is an additional observable implication of the hypothesized argument.

Our second results suggests a negative impact of party leadership domination on congruence. The corresponding arguments in the hypothesis section are about the estimate of party constituencies being more noisy in this situation. In other words, the standard error in the estimate will be larger. This is exactly what we test in Model 4 with the dependent variable being the standard deviation of the party constituents distribution. Again we find confirmation for the hypothesized mechanism: Controlling for a number of covariates, parties with strong leaders have voters with broader distributions of ideological preferences.

Linking the empirical results back to Figure 1 we find that that the parties in the top right corner are the least congruent because they combine a strong horizontally integrative structure (mass-membership based) with high leadership domination.Footnote 8 Besides the parties shown in the figure, we find other examples of established “Volksparteien” with this combination, for example, the Swedish Social Democrats, the French UMP and both the Portuguese Social Democratic and the center-right PSD/PPD. These old and established parties seem especially prone to lose contact with their constituencies.

4. Conclusion

We essentially live in a party democracy (Sartori, Reference Sartori1968), but are parties able to deliver high quality representation? Several theories cast a negative outlook on this question: processes such as oligarchization, cartelization and presidentialization point towards an increasingly narrow representation of interests. Because members have left parties en masse (Van Biezen et al., Reference Van Biezen, Mair and Poguntke2012) and the electorate has stopped identifying with parties (Dalton and Wattenberg, Reference Dalton and Wattenberg2000), parties seem to have lost legitimacy and today only “rule the void” (Mair, Reference Mair2013). Regardless of these developments, our results demonstrate that parties still matters for representation and that the degree to which they fulfill their representational function varies considerably with their organizational structure. According to our findings, parties without significant membership and not dominated by a strong leader are best in achieving congruence with their constituencies. If we follow (Dalton, Reference Dalton1985) and see non-mass parties as catch-all parties, the result that these parties are close to their voters is not surprising as their vote-seeking ambitions force them to pay close attention to what their voters want. At the same time these results also suggest that zealots within the party bias signals from the party constituents and contribute to weak congruence. The result that leadership dominated parties are less congruent with their voters than activist dominated parties is more worrisome as it can be read as a sign of a detachment of party leaders and the public. On the other hand, it also suggests that leadership-dominated parties, more than activist-dominated parties, manage to cobble together a broad coalition of voters with diverse preferences. In total, our prospect for the future of party democracy is mixed: While the development towards more leadership dominated parties (see Schumacher and Giger, Reference Schumacher and Giger2017) will be associated with a decrease in congruence, the decline in mass-membership might serve a counter-trend and outbalance the worsening of congruence through more leadership dominated parties.

We have concluded that activist-dominated parties with small membership numbers produce the highest congruence with their voters. Although their membership is small, it is likely that in these parties the membership is more representative of the party voters. There may be two reasons for this. First, because of the small size there is arguably less apathy and therefore higher participation rates of members. The fact that members have a strong say in party policy should further reduce apathy. Party members matter. It may therefore be more appealing for ordinary party voters to be members. Only zealots take the time and effort to push through their agenda in a party in which their voice is severely limited. People with ordinary opinions are far less likely to go through the trouble. This is all speculative, and leads to new questions about how party structures motivate different behavior from party members.

A challenge to modern parties that we have not addressed in this study is the decline in party identification and the resulting difficulty of parties to represent both loyal partisans and the increasing share of more volatile voters. How are parties with different degrees of party organization able to react to these developments and do we see a systematic advantage for one or the other group according to party organizational features? These are interesting questions that could be pursued in future research.

It remains further to be seen whether and under which conditions ideological closeness pays out electorally. We have deliberately stayed away from making any claims about close congruence being favorable to electoral success as this link is far from obvious. Importantly, close congruence is never the sole achievement of political parties. If the responsible party model is undermined because voters do not base their electoral choice on policy or ideological criteria, the task of representing their constituencies ideologically becomes tremendously difficult for parties of any kind. Taking this dimension of the representation process into account could also be an interesting avenue for future research.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2019.54.