Introduction

In a remote corner of Greenland a battle for information, a fight for weather observations unfolded during the World War II. This conflict culminated in several skirmishes between German and allied forces, and U.S. bombers conducting air strikes on Northeast Greenland from their base in Iceland. The events have since been described in popular prose (Balchen and Ford Reference Balchen, Ford, Balchen, Ford and La Farge1944; Weiß Reference Weiß1949; Howarth Reference Howarth1957; Balchen Reference Balchen1958) as well as in scientific literature (Blyth Reference Blyth1951; Selinger Reference Selinger2001; Dege Reference Dege and Barr2004; Krause Reference Krause2007; Skarstein Reference Skarstein2007). The remains of the bombed and burned-down buildings in Northeast Greenland, however, have remained virtually untouched since the war. Today the dramatic historical events can be analysed by interdisciplinary historical-archaeological studies of the relicts.

In 2007, archaeologists from the National Museum of Denmark conducted the first preliminary documentation of the former allied station at Eskimonæs (Eskimo Point) on Clavering Ø (Clavering Island). Finally in 2008, a detailed historical-archaeological investigation and mapping was conducted on the same site at Eskimonæs, as well as on the site of the former German weather station Holzauge in Hansa Bugt (Hansa Bay), approximately 100 km north of Eskimonæs. In this article we will report on the preliminary results of our field work at these two localities, and recount the historical events in this remote theatre on the basis of our comparative archival studies. The results of the fieldwork have been reported more comprehensively in a report of the National Museum of Denmark (Jensen and Krause Reference Jensen and Krause2009).

War relics in the landscape

At first glance the remains of the burnt weather station at Eskimonæs resemble an untidy scrap heap with rusty chimney pipes, tin cans, broken plates and melted instruments. On closer inspection, however, the scrap heap blurs the outline of a rectangular building (Fig. 1). In a corner where the kitchen was located, a concentration of melted cast iron pots, enamelled plates, knives and forks can be seen, and in the centre of the house, on the same spot where there once stood a cabinet with glassware and dinnerware, lays a large cake of molten glass and broken crockery. In the sand beside the porch at the front of the house, a coir mat is lying quite unharmed! A closer look thus reveals that the apparent scrap heap at Eskimonæs in reality is an exceptionally well preserved fire site from the war, and that most of its items are situated precisely where they hit the ground when the house burned down and collapsed some 65 years ago.

Fig. 1. Tilo Krause drawing the ground plan of the main building at Eskimonæs. Photo: Jens Fog Jensen 2008.

The published testimonies are conflicting or inconclusive as to the history of destruction of the Eskimonæs station. For example, the German chief meteorologist Gottfried Weiß recounts that his own commandant, Lieutenant Hermann Ritter ‘had the beautiful station destroyed, as he deemed it necessary for our security’ (Weiß Reference Weiß1949: 113) [translated from German]. The Norwegian-American aviation pioneer Bernt Balchen, who was in charge of the American bombing raid on Eskimonæs on 14 May 1943, on the other hand reports that: ‘Although we assumed the station was deserted, we carried out our orders, dropped our bombs, strafed the buildings, and left them burning as we headed back to Iceland’ (Balchen and Ford Reference Balchen, Ford, Balchen, Ford and La Farge1944: 28).

Obviously Eskimonæs cannot have been burned twice; yet since the station complex comprised no fewer than six buildings, it is theoretically possible that the different structures could have been destroyed by different war parties. During the archaeological investigation in 2008 at Eskimonæs, we focused on the destruction history of that station. Since the Germans attacked Eskimonæs using ground personnel and the subsequent American attack was conducted by aircraft, we assumed that clues to the incineration of the structures could be found on the preserved fire sites. A direct bomb impact, for example, would destroy and atomize the buildings in a manner different from that of an arson attack by infantry.

Historical background

Modern warfare at the time of the World War II had become more than ever dependent on weather forecasts, not least in light of the considerable advances in aviation during the previous decades. Reliable prediction of the weather over Europe in particular, is heavily dependent on observations from Greenland and the North Atlantic, as the path of the cyclones moving from west to east is more or less dictated by the position of cold Arctic air masses in relation to warmer temperate air masses. At the outbreak of the war, weather observations from stations on allied controlled territory were increasingly transmitted in code, thus denying Germany access to those hitherto internationally accessible weather data. In order to fill this enormous gap, Germany had to create her own network of meteorological stations that could provide weather data (Selinger Reference Selinger2001).

The German military weather services in the Northern Atlantic were organized by both Luftwaffe and Kriegsmarine, conducting weather observations not only via aircraft surveillance and automatic weather stations, but also by establishing manned weather stations in the remote polar regions. In Greenland, manned weather stations were established exclusively by Kriegsmarine, for the first time in the summer of 1942. Yet already in 1940 and again in 1941, British and American coast guard vessels had detected and arrested two German-friendly weather parties sent out to Northeast Greenland from occupied Denmark and Norway, and manned by Danes and Norwegians, respectively (Skarstein Reference Skarstein2007).

Against the background of this obvious threat, the North-East Greenland Sledge Patrol was established in 1941 as an allied joint venture between the Greenland and the American authorities (Odsbjerg Reference Odsbjerg1990). The objective of the patrol was to survey the inaccessible and uninhabited shores of Northeast Greenland by dog sledge, and to report the presence of foreign intruders to the Greenland authorities. The patrol comprised some 10 to 15 Danish and Norwegian trappers who had worked in Northeast Greenland until the outbreak of the war, and thus were familiar with the terrain. Also enrolled were a number of skilled and experienced Greenlandic sledge drivers from the Scoresbysund area. All members of the patrol were given police authority, and it operated from three base stations covering the vast area, with Scoresbysund in the south, Ella Ø in the middle and Eskimonæs (Clavering Ø) in the north. The two latter stations had originally been built as twin stations for the Danish scientific ‘Three-Year Expedition’ in 1931–1934. Thus the main buildings of these two stations were virtually identical houses (Koch Reference Koch1955). Seen in a contemporary perspective, they were modern buildings well equipped with radio and electrical power supply, making them well suited to be used as combined police- and weather stations for the North-East Greenland Sledge Patrol.

The enemy detected

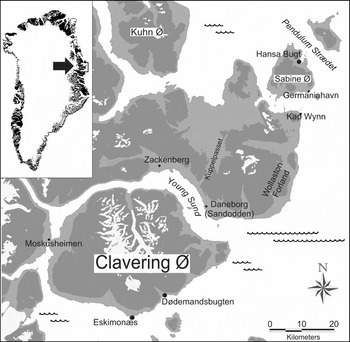

The first confrontation between the Wehrmacht and the North-East Greenland Sledge Patrol took place in early spring 1943, when the patrol was on that year's first northbound survey from Eskimonæs to Sabine Ø (Sabine Island) (Fig. 2). The team consisted of the Danish trapper Marius Jensen and the two Greenlandic sled drivers William Arke and Mikael Kunak. On the afternoon of 11 March they were crossing the frozen strait between Wollaston Forland and Sabine Ø, heading towards the old trapper's hut Germaniahavn at that island's southeastern tip. Upon arrival, the three men spotted two people fleeing from the hut by the beach and into the hills behind. In the abandoned hut they found a German uniform jacket, two sleeping bags and fresh meat from a recently slain polar bear. These unequivocal signs of hostile activity had to be reported back to the base at Eskimonæs immediately, so without hesitation the three men turned their sledges southward to the nearest hut at Kap Wynn in order to spend the night.

Fig. 2. Map of the Clavering Ø/Young Sund area with the localities mentioned in the article.

In the meantime, the two Germans that had fled from the hut at Germaniahavn headed across the island to their base in Hansa Bugt in order to alert their companions that they had been discovered. This base camp in Hansa Bugt was in fact the first German weather station to have wintered undetected in Greenland since the outbreak of the war. The station with the codename Holzauge had a crew of 18 men and had been established in the previous summer and autumn (1942) in the greatest secrecy. Now the German commandant, Hermann Ritter, had to prevent the three Danish sledge drivers from passing on their knowledge about the German presence at all costs. He immediately sent out three patrols on foot to comb the island southward towards Germaniahavn. After finding the whole island and the Germaniahavn hut clear of their opponents, two of the three teams returned to Hansa Bugt. The third, however, consisting of chief meteorologist Gottfried Weiß, radio operator Günther Nawroth and the two young stokers Friedrich Littmann and Heinz Hardt, proceeded and followed the Danish sledge trail back over the sea ice and up to the hut at Kap Wynn.

By that time, the evening darkness had already fallen, and gathered inside the tiny hut at Kap Wynn, Marius, William and Mikael were warned by their barking dogs outside, of the German patrol approaching. The three men had no time to harness their dogs, and on foot they fled into the hinterland hills from their invisible opponents that were closing in. They had to leave all three dog teams behind in front of the hut, and in the hurry, Marius even forgot his diary on the bunk inside. From the hinterland hills he witnessed how the German team occupied the Kap Wynn hut, and a little later he moved southward towards Clavering Ø on foot, following the tracks of his two comrades who had marched off some minutes before him. On 13 March the three men arrived to Eskimonæs, where they reported on the German presence on Sabine Ø.

After the Danish sledge team had fled, Weiß and his three companions had occupied the cabin at Kap Wynn, pleasantly surprised to find their opponents’ abandoned warm dinner and hot coffee left on the table. Even though they had not succeeded in their main task of preventing the Danish team from escaping and spreading news on the German presence, their pursuit expedition had given quite favourable results. Especially Marius's diary represented useful booty providing the Germans with accurate information about their opponents. Furthermore, the seizure of the dog teams resulted in a great improvement in their mobility, as they had not brought dog teams to Greenland themselves. The next morning (12 March 1943), the four Germans returned to their base in Hansa Bugt on the three dog sleds seized from the Danes. None of them had ever travelled by dog sledge before, so the rather short distance from Kap Wynn to Germaniahavn alone took them five hours, and Weiß described this trip with much self-irony (Weiß Reference Weiß1949: 110–112).

Attack on Eskimonæs

After the incidents of 11 March 1943, Ritter informed his superiors at the naval command in Tromsø (occupied Norway) about the confrontation (Fig. 3A). Shortly after, he received orders to attack and neutralize the allied station at Eskimonæs (Fig. 3B). An operation on that remote target had now become possible for the Germans, since Weiß's group had seized the three dog teams at Kap Wynn, thus enhancing the mobility of the garrison. In Hansa Bugt some days were spent on training at dog sledding, and especially the young stoker Friedrich Littmann established a good rapport with the dogs and took pleasure in sledding. On 19 March, ‘Stoßtrupp Eskimonæs’ departed from Hansa Bugt, led by Ritter himself, accompanied by 5 companions. Apart from Nawroth and Littmann, who had already participated in the pursuit and dog seizure at Kap Wynn, the small force consisted of the party's medical officer, Dr. Rudolf Sensse, as well as the young seaman Karl Kaiser and the Czechoslovak engineer Vaclav Novotny.

Fig. 3A. Telegraph message from Ritter to the German naval command in Tromsø (occupied Norway), where he reports the discovery of his secret weather station in Hansa Bugt. Archives: Bundesarchiv-Militärarchiv, Freiburg (Germany).

Fig. 3B. Reply from ‘Marine-Gruppenkommando Nord’, in which Ritter is ordered to neutralise the allied station at Eskimonæs. The priority of the operation is emphasised by the fact that ‘Gruppenkommando’ is willing to accept a temporary interruption of the crucial weather observations in order to accomplish the attack. Archives: Bundesarchiv-Militärarchiv, Freiburg (Germany).

At Eskimonæs, meanwhile, the North-East Greenland Sledge Patrol was on the alert and prepared for a German attack, ever since Marius Jensen, William Arke and Mikael Kunak had reported back from the first confrontation at Kap Wynn. Gun posts, emergency depots and even small bomb shelters had been set up in the surrounding terrain. The commanding officer of the station, Captain Ib Poulsen, had sent out two sled teams in order to warn and assemble the rest of the patrol members still on patrol in the vast area and unaware of the German presence. After those teams had departed, there were still five men left at Eskimonæs; but according to an internal agreement in the patrol, all Greenlandic patrol members were exempted from combat participation. This meant that the two Greenlandic sledge drivers residing at Eskimonæs at that time, William Arke and Evald Simonsen, were to leave the station too, as soon as it would be attacked. With these two men also gone, eventually there would only be three persons left to defend Eskimonæs, until the two teams on patrol returned with the reinforcements. These were Ib Poulsen himself, the young radio operator Kurt Olsen and the old Norwegian trapper in his mid-fifties, Henry Rudi, who had spent nearly his entire life as an Arctic hunter, first on Svalbard and since then in Northeast Greenland.

On the evening of 23 March, after nightfall, Ritter's combat party of six men arrived at Eskimonæs. Unfortunately, at that time, the two sled teams with the reinforcements had not returned yet, which meant that the station now had to be defended by the meagre force of three men. Neither of the combatants ever knew the number of their opponents during this confrontation, as it took place in complete darkness and zero visibility. The description of the skirmishes that followed now is reminiscent of the climactic scenes in a classical western movie, rather than of a genuine military attack. One reason for this is Ritter's personal acquaintanceship with some of his now opponents in the patrol; Henry Rudi in particular, whom he knew from his own years as an Arctic trapper on Svalbard back in the 1930’s. Ritter's general behaviour during the attack on Eskimonæs indicates that his character in many ways was rather one of an adventurer than of a soldier: The confrontation thus starts with an attempt to negotiate, as demonstrated by the following reports from three participants in the incident.

Ib Poulsen, the Danish commandant of Eskimonæs: ‘Immediately when I came out, I heard footsteps nearby, closing in on my position, and I shouted in German: “Halt, who goes there?” [. . .] Instead of a reply, I was asked in broken Danish who I was, which I obviously did not answer either. It was then [. . .] expressed a wish to have a word with Mr. Poulsen. [. . .] I told them still in German that it was not possible to have a word with anyone tonight, and that they had to withdraw’ (Jensen and others Reference Jensen, Olsen, Poulsen, Nielsen and Ziebell1945: 290) [translated from Danish].

Henry Rudi, the Norwegian trapper and subordinate to Poulsen at Eskimonæs: ‘Immediately, Ib Poulsen took command while the rest of us rushed out of the house and to our posts. He shouted: Wer da! – Everything turned silent for a few seconds. – “Die deutsche Wehrmacht”, it was answered. – Poulsen shouted back that one single man might come over to us, but unarmed. The reply came in perfect Norwegian: ‘Is Poulsen present?’ [. . .] That voice sounded familiar to me. It was Ritter. – Ritter whom I knew as a friend, – now he was confronting me with a weapon in his hand. [. . .] I became damned angry’ (Rudi Reference Rudi1958: 229) [translated from Norwegian].

Friedrich Littmann, the German stoker and participant in Ritter's combat party: ‘But now one light after the other was switched off, and shortly after that a voice shouted from the darkness towards us: “What do you want, not a step closer or I'll shoot.” Everything in German. We wanted to storm, but Ritter held us back’ (Littmann Reference Littmann1987:36) [translated from German].

This short exchange of opinions made it clear to both opponents that unless one side deliberately chose to disobey their principal orders, a fire fight was now inevitable. The German group was numerically and technically superior, and with a hail of bullets, the German machine gun completely outperformed the old hunting rifles of the patrol. After less than twenty minutes, the three defending patrol men were forced to flee and abandon the station. Rudi and Olsen walked to the hunting station Moskusheimen some 40 km to the northwest, where Rudi previously had wintered several times as a trapper (Fig. 2). Poulsen chose to stay in the vicinity of Eskimonæs for several hours after the attack, hiding in the cliffs behind the station. From here he observed the Germans’ further movements until the next morning. Then he also marched off and headed for Moskusheimen.

On that day, 24 March, the German team took a day off at Eskimonæs, investigating their opponents’ secret papers, destroying the radio equipment, and enjoying the station's abundant supplies. And as yet another manifestation of Ritter's personal familiarity both with the working conditions of an Arctic trapper on the whole, and with some members of the patrol in particular, he ordered his men to assemble the personal property of the patrol members, including their valuable trapping bag of numerous fox pelts, in a little cabin, which was to be spared from demolition. On the top of the piled furs and saved goods, Ritter placed a written justification for his intended destruction of the station, including a formal complaint about his opponents’ alleged use of soft nosed ammunition, which he had found large quantities of in the station's supplies. He argued that their use was violating the rules of war, referring to the Hague Conventions (Balchen and Ford Reference Balchen, Ford, Balchen, Ford and La Farge1944: 26). On the morning of 25 March, the station was demolished and set on fire, except for the hut with the skins and personal belongings, and the German troop then headed back towards their station in Hansa Bugt. On their return trip they rested at the trapping station Sandodden (now Daneborg) at Young Sund (Fig. 2).

At the same time, and unaware that Eskimonæs had been attacked, Eli Knudsen, Marius Jensen and Peter Nielsen of the patrol were heading south from Kuhn Ø towards Clavering Ø. Being one of the two teams, which Poulsen had sent out for reinforcement, they were now on their way back to Eskimonæs. On the evening of 26 March, they were heading for Sandodden, where they would spend the night, completely unaware that Ritter's party on this very day was staying at the same spot! Eli Knudsen, who had wintered at Sandodden as a trapper several times before, drove ahead of his two comrades, and eventually continued towards the station on his own. When he approached Sandodden on his sled, he was accidentally shot by the Germans, who obviously had misinterpreted his approaching as an attack. Eli Knudsen would remain the North-East Greenland Sledge Patrol's sole casualty in this war. His two comrades were taken prisoner by the Germans, when they arrived to Sandodden the next day. After a few days in German custody at Germaniahavn, however, Peter Nielsen was granted his freedom by a curious decision of Ritter's. Permitted to travel back to Sandodden with the objective of burying Eli Knudsen's corpse, Peter jumped at the chance and made his way directly to the south, where he eventually became reunited with his comrades of the North-East Greenland Sledge Patrol. Marius Jensen, on the other hand, was as a POW taken on a northbound dog sledge journey together with Ritter. It is beyond the scope of this article to deal in depth with the drama and events occurring between Ritter and Jensen on this journey, but shortly after their departure the roles were reversed, and Jensen travelled south with Ritter as the captive. On 14 May, they arrived at Scoresbysund, where Ritter was handed over to the American authorities.

After the Germans had burnt and left Eskimonæs on 25 March, the station lay deserted for seven weeks, while the patrol withdrew southward, assembling at their next base to the south, Ella Ø, and eventually retreating to their southernmost base, Scoresbysund (now Ittoqqortoormiit). Finally on 14 May, Eskimonæs was bombed by the U.S. Army Air Force, as it was believed that the German party had seized and occupied the abandoned station right after the attack back in March.

Investigation of the fire site at Eskimonæs

In 2008, we conducted a detailed mapping of the former main house at Eskimonæs. It was striking that the distribution of artefacts found in this fire ruin still reflected the original ground plan of the building, as published in 1937 by the constructors themselves in the Three Year Expedition's popular account (Seidenfaden Reference Seidenfaden and Thorson1937: 59) (Fig. 4). From this visualisation it becomes apparent that even though some elements, such as the stove, have changed their position, the majority of the objects is still situated where they hit the ground during the fire in 1943. Rust red twisted iron tubes are dominating among the charred rubble. Those are the collapsed chimney flues, with their bases pointing towards the original positions of the main room's stove and heating stove, respectively, and thereby indicating their own original positions above either of these two. In the western part of the ruin, we see a concentration of large rusty cabinets and fittings from the radio installation, which is in perfect accordance with the location of the radio room on the published ground plan. Finally, in the north-western corner, where the workshop used to be, a major power transformer can be spotted. This particular detail matches with the following description of the workshop in the popular account on the station's construction in 1931: ‘Every cubic inch of space is occupied, and even under the table, there was still space enough to set up the large generator, which shall transform the motor's currents into the high voltage required to operate the radio transmitter’ (Seidenfaden Reference Seidenfaden and Thorson1937: 62) [translated from Danish]. This method of comparing the archaeological artefacts with the historical sources made it possible to identify many of the objects found on the site, as their position is often as close to the original as one might expect when a house burns down, and the non-combustible objects drop to the ground.

Fig. 4. The original ground plan of the main building at Eskimonæs as published in 1937, here superimposed on the ground plan of artefacts registered on the fire site in 2008 (compare Fig. 1). Along the front and northern side, the perimeter of the building can be followed by the slightly raised gravel foundation, and in many cases the location of artefacts closely resembles their original place within the building. Most of the radio equipment, for example, is found in the radio operators’ room, and in the main room, a large ‘cake’ of molten glass and crushed china indicates the original place of the cabinet, where most of the dining service was stored.

Even some of the smaller objects mapped on the site in 2008, could be identified, from historical photographs taken at Eskimonæs before its destruction. This applies for example to an ashtray, which is seen on the table in one of the station's six sleeping quarters, appearing on an image in Lauge Koch's report on his 1930's scientific expedition programmes in and around Eskimonæs (Koch Reference Koch1955: 296) (Fig. 5A). In 2008, we found the same ashtray, albeit in a rather splintered condition, in the area of one of the neighbouring quarters in the ruin (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5. A) Personal quarters at Eskimonæs in the 1930’s, with characteristic ashtray on the table. Publication: (Koch Reference Koch1955). B) The same ashtray, found in the area of one of the neighbouring quarters in 2008. Photo: Jens Fog Jensen.

As for the history of destruction of the building in 1943, the archaeological remains at Eskimonæs do not reveal whether the German or the American party was the arsonist. Nevertheless, there are several striking traces of demolition that cannot be attributed to the American air bombardment, and therefore must result from the German ground activities on the site. The radio mast for example has been cut down and lies undisturbed where it has collapsed (Fig. 6A). Since the American party acted solely from the air, this destruction must have been carried out by the German troops. Another obvious feature left by the German attack is a rectangular hole in the door of a rusty safe, found in the fire site. This hole happens to match exactly with a pickaxe that was found nearby (Fig. 6B). The fact that the shaft of the pick is burned off, indicates that this tool must have burned together with the building, thus establishing that it was used on the safe prior to the incineration. Assuming that this indeed is the pick that was used to break up the safe (and what else would it really be?), and of course that the patrol had no reason to break up a safe at their own base station, this tool must have been swung by one of the German soldiers, since they were the last people to visit Eskimonæs on the ground before the incineration of the buildings in 1943.

Fig. 6. Examples of German ground demolitions at Eskimonæs: A) The stub of the radio pole, sawn by German soldiers, with the collapsed pole visible behind it. B) Safe broken up with a pickaxe, where the shaft later burned off. (The pick was originally found outside the ruin, but happened to match the rectangular hole in the lid of the safe, where it was placed by the author for this picture.) Photos: Jens Fog Jensen.

The bombing of Eskimonæs

Traces of the U.S. aerial bombardment and strafing were also recorded. The most conspicuous is a number of cartridge cases from a 50 calibre Browning machine gun, found among the ruins of Eskimonæs, as well as in the surrounding terrain. This particular calibre was not used by the Germans, and in addition, several of the cartridge cases have characteristic stroke marks on their bases, indicating that they have been dropped on the rocks from a great altitude (Fig. 7A). A projectile of the same calibre was found in the sand near the rocks, where the radio mast was located. This projectile must have hit either a snowdrift or the soft sand, as it is not deformed in any way.

Fig. 7. Traces of the American air raid on Eskimonæs: A) Cartridge case from machine gun, calibre 50, with a characteristic stroke mark on the base, indicating that it has been dropped on the rocks from a great altitude. B) Shrapnel from bombs found on the cliff in front of the Eskimonæs station. C) Marks of bomb detonations on the ice-scoured rocks, found in the same area where the shrapnel also was concentrated. Photos: Jens Fog Jensen 2008.

A systematic survey of the terrain also revealed some tangible traces of the American bombs. On the small rocky point to the east of the burnt station, a considerable amount of shrapnel has been recorded (Fig. 7B), and in the generally smooth, ice scoured granite cliffs of this rocky point, we located two areas with swarms of conical grooves, which we believe have been left by the impacts of shrapnel as well. In the centre of each swarm is a distinctive area of crushed and pulverized rock; presumably the points of detonation of the bombs (Fig. 7C).

Finally, the absence of shrapnel penetration among the numerous chimney flues and metal objects in the ruins, together with the fact that all of the ruined houses and huts appear well defined rather than disturbed by detonations, suggests that none of the bombs dropped during the American air raid on 14 May 1943 hit their targets. On the contrary, distinctive marks of bomb impacts are solely found on the aforementioned rocky point to the east of the Eskimonæs houses. This combined evidence establishes the rocky point itself, and most likely the sea ice to the east of the station as the principal areas to have been hit by the American bombs, rather than the station buildings. The principal destruction of Eskimonæs must therefore be attributed to the German ground activities in March 1943, notwithstanding the possibility that some buildings, which the Germans originally may have spared, still might have been set ablaze by the American strafing that ignited flammable liquids as well as timber structures.

The secret German station on Sabine Island

100 km north of Eskimonæs, the German opponents of the North-East Greenland Sledge Patrol had established their base on Sabine Ø (Sabine Island). Here, in the natural harbour at Hansa Bugt (Hansa Bay), we find Wehrmacht fire sites comparable to the ruins of the Allied station at Eskimonæs.

Already in August 1942 and in deep secrecy, this German meteorological expedition codenamed Holzauge [Knot in wood] had crossed the North Atlantic on their vessel Sachsen and established a weather and radio station on this spot. Their primary objective was the daily collection of weather observations and the transmission of those data by radio to their naval command in occupied Norway. As already mentioned earlier, Holzauge was a party consisting of 18 men under the command of the slightly enigmatic mariner and polar adventurer, Lieutenant Hermann Ritter. It was the first regular German weather expedition sent out to Greenland by the Kriegsmarine in this war, and also the first to succeed in wintering undetected on these shores. Unlike the two earlier, unsuccessful German weather expeditions to Greenland in 1940 and 1941 (Skarstein Reference Skarstein2007), this one was, with only two Czechoslovak exceptions, entirely manned by Germans.

The station at Hansa Bugt comprised the expedition vessel Sachsen herself, anchored in the bay and eventually closed in completely by land fast ice, as well as two huts, Alte Hütte and Neue Hütte, which were erected on land by the crew. The icebound ship served as the main station throughout the winter, providing quarters for the majority of the men, and housing the entire weather and radio equipment. Alte Hütte was the first house erected on shore immediately upon arrival in late August. It was originally used as living quarters for those members of the crew, who were not residing on the ship, providing bunk beds for eight men as well as a stove. By March 1943, however, this building took over the functions of the main station from the ship, with the meteorological as well as the radio and transformer equipment collected under its roof, in addition to the living facilities it had already housed up till then. It thus turned into the station's cardinal component and would retain this function for the remaining months until its destruction. Neue Hütte had been built shortly after Alte Hütte in autumn 1942, but was not occupied until March 1943, serving exclusively as living quarters for the crew of the ship. The reason for concentrating crew and equipment on the two huts in March was their safety. The men on board the icebound Sachsen, increasingly exposed with the approach of spring, began to fear the threat of aerial bombardment and did not want to be sitting ducks for American bombing planes (Weiß Reference Weiß1949).

Unlike in the case of Eskimonæs, the historical records on the destruction of these facilities are quite non-conflicting, since it has been recounted by several eyewitnesses of the German garrison that Alte Hütte was strafed and burned down, when the station, not quite unexpectedly, as we have seen, was bombed by the U.S. Army Air Force on 25 May 1943. Neue Hütte on the other hand, had survived the American air strike, but was incinerated by the German soldiers themselves on the day of their evacuation (17 June 1943). At the time of the evacuation, which was carried out by a Dornier flying boat landing in Pendulum Strædet, the ship Sachsen was still stuck in land fast ice in Hansa Bugt, and was therefore sunk by her crew, immediately before they boarded the aircraft and left Greenland. Consequently, this principal component of the German station must be assumed to be comparatively well preserved still today, being situated some 40 m under the surface of the icy Hansa Bugt waters, yet it is inaccessible to our current archaeological efforts. Our focus therefore, naturally, is on the remains of the station's land facilities. The archaeological relicts at the fire sites of Alte Hütte and Neue Hütte are equally well preserved and perhaps still even more spectacular than the debris at Eskimonæs.

Investigation of the fire sites at Hansa Bugt

Both ruins are easy to identify as charred, rectangular areas on the ground, covered with numerous rusty metal objects and molten charred inventory; and in both cases the position of the former outer walls is clearly marked by foundations set in stones along two sides. Alte Hütte, having been the heart of the station for the final months in 1943, appears more monumental than Neue Hütte. Its characteristic enamelled stove, the rusty radio cabinets, scientific measuring equipment and hydrogen productive devices (for weather balloons) can be identified even at distance (Fig. 8). During the American air attack on 25 May 1943, the residents of Alte Hütte had to leave the building and took cover in the surrounding hills. The entire equipment was thus left behind in the burning house, including not only the radio and valuable scientific gear, but also ammunition and spare parts for the firearms. All those objects can be readily identified still today, even though they have turned rusty and are partly blasted by exploding cartridges, such as the machine gun drum magazine shown on Figure 9A.

Fig. 8. Alte Hütte in Hansa Bugt, with Jens Fog Jensen taking pictures of the ground plan. The characteristic, white enamelled stove is seen in the centre of the ruin. Photo: Tilo Krause 2008.

Fig. 9. A) Drum magazine of a German machine gun at Hansa Bugt, exploded during the burning of Alte Hütte. B) A pair of air dropped German supply containers on the beach at Hansa Bugt. Photos: Jens Fog Jensen 2008.

The German garrison, however, had taken precautions against air strike by setting up caches with provisions, tents, fuel and spare radio equipment in the surrounding terrain, so that they could survive and maintain contact with Norway in case the huts were lost. Two hand drafted maps of the station from March 1943, indicating the positions of these caches as well as their original contents, are preserved at Bundesarchiv-Militärarchiv in Freiburg, Germany. With the help of those, we could locate and identify traces of these depots in the vicinity of both Alte Hütte and Neue Hütte. But also further away in the hills and along the southern shore of the bay, some relicts could be registered. Remnants of telephone wires connecting the two cabins as well as the bay (that is the ship), for example, are seen in the landscape, and there are also wires running way up to the plateau in the southwest, where there had been a temporary observation post. Among the rather spectacular objects in the terrain are two air dropped supply containers on the beach (Fig. 9B), as well as a rubber dinghy, which we assume had been used to ferry people and goods back and forth between the shore and the ship in the first weeks after the Germans’ arrival, when the waters of the bay were not yet frozen.

After the American airstrike, the German troop withdrew to an improvised Notlager [emergency camp], situated in a ravine high up in the hills in the southwestern part of the Hansa Bugt area. Well hidden immediately below a vertical cliff, this spot seemed to provide shelter from any further aircraft attacks (Fig. 10). Here, in tents, the men spent the final three weeks of their stay in Greenland, until they were evacuated by flying boat in two phases on 7 and 17 June 1943. Since Notlager was not only functioning as an emergency camp with sleeping and cooking facilities, but also as a small scale fortress and radio station, the ravine reveals quite a variation of objects as well. The location of at least two tents can be identified from two circular clusters of tent pegs with attached pieces of guy rope, and in the areas adjacent to these, we found burnt remains of radios, as well as pots, plates and a number of weapons including a machine gun (Fig. 11A). All these objects appear to have been piled up and incinerated before the last soldiers and weather people of the Holzauge party were evacuated from Hansa Bugt on 17 June 1943.

Fig. 10. Notlager: In this ravine under a cliff in the southwestern part of the Hansa Bugt area, the German garrison established their emergency camp after the American airstrike on 25 May 1943. Note: Tilo Krause barely visible between large rocks in centre of the marked circle. Photo: Jens Fog Jensen 2008.

Fig. 11. A) German machine gun (MG 34) left among the rocks at Notlager in Hansa Bugt. B) Two types of charred pasta from the fire site of Alte Hütte. Photos: Jens Fog Jensen 2008.

By the time Holzauge was evacuated from Greenland, the next Kriegsmarine weather expedition to these remote shores was already in preparation. Operation Bassgeiger [Double-bass player] would become the second and last German war expedition to winter successfully in Northeast Greenland. They established themselves still further north, at Kap Sussi on Shannon Ø, where they ran a meteorological station from autumn 1943 until early summer 1944 (Frederiksen Reference Frederiksen2008). The two final German attempts to establish weather stations in Northeast Greenland during the war, operations Edelweiss and Edelweiss II in autumn 1944, were not successful, as they were captured by the U.S. Coast Guard, before they even became operative.

Perspectives for historical archaeology in the Arctic

The physical remains left by the garrison in Hansa Bugt (Sabine Ø) appear today as largely undisturbed ever since the last occupants left the site back in 1943. At Eskimonæs (Clavering Ø), a similar conclusion can be drawn about the remnants of the allied station, whose buildings originally dated back from the Danish ‘Three Year Expedition’ in 1931–1934.

All those ruins in the Northeast Greenland National Park have since become slightly covered by drifting sand or extremely sparse polar vegetation, but not to such an extent that larger objects are obliterated. The political and military drama between the World War II's global combatants is thus archaeologically imprinted on the ground of these barren and desolate regions, with the ‘battlescapes’ of the western world still virtually untouched and readily visible on the surface. The archaeological objects, like the inanimate scenery of the surrounding landscape itself, appear as if they were caught in a time warp. A microcosm of the war's bloody conflicts is projected into a wilderness populated by a few dozen individuals who most of the time were busy surviving in the harsh climate.

The preserved objects, undisturbed as they are, prove to have great potential for adding new details and odd aspects to the story of the war. For example, they offer a rare opportunity to visualise the dramatic events of combat actions (Fig. 11A) as well as the rather mundane everyday life qualities of the weathermen and soldiers on service in these latitudes in the 1940’s. Noodle soup appears to have been on the menu more than just once in Hansa Bugt (Fig. 11B), but the charred peas and coffee beans found in the ruins of Eskimonæs also indicate that despite the wartime scarcity of these products in Europe, this remote spot in the Arctic could obviously be supplied with quite considerable amounts of these coveted goods; a tiny archaeological detail, which nevertheless illustrates the increased importance of the Arctic weather services for modern warfare in those days.

Historical archaeology in the Arctic, as our investigation shows, is an interdisciplinary approach not only perfectly suitable for this particular historical subject, but also with considerable future potential in the field. The exciting popular narratives of the weather war's participants (Balchen and Ford Reference Balchen, Ford, Balchen, Ford and La Farge1944; Jensen and others Reference Jensen, Olsen, Poulsen, Nielsen and Ziebell1945; Weiß Reference Weiß1949; Howarth Reference Howarth1957) acquire tangible physical confirmation from the exceptionally well-preserved sites and objects on the original locations in Northeast Greenland. The historical sources, in return, provide names and profiles of the protagonists, details of their lives and thus explanations of their lines of action in the conflict, and sometimes pretty detailed information about places, hours and even minutes of the dramatic incidents that have resulted in the post-conflict state of the sites as we see it today. Furthermore, as we have seen, the historical sources can also contribute to the actual discovery of previously unrecorded objects on location, as well as help making sense of the physical distribution of the remnants.

In the course of climate changes, the formerly remote and generally inaccessible arctic regions are currently becoming more and more accessible. Simultaneously, the natural conditions, which hitherto secured the objects’ preservation, such as the annual coverage by snow and ice, are in obvious retreat. Our detailed mapping of the two sites in 2008 has recorded the objects’ current status in this process, thus providing a professional basis for future efforts in the preservation of those exceptional relics from the weather war in the Arctic. We therefore hope that this initial historical-archaeological project will be helpful in future assessments of Greenland's historical remnants and their speed of deterioration, thus enabling specific measurements to be taken for their protection and for the heritage interpretation, similar to some of the measurements already taken on historical monuments in Svalbard (Bjerck and Johannessen Reference Bjerck and Johannesen1999) and Antarctica (Roura Reference Roura2009).