Introduction

To a modern observer, the image of Captain Scott and his men leading a trail of long-haired Siberian ponies across the Antarctic wastes in 1911 appears incongruous. Surely, runs the argument, these men would have known such animals were not well suited to this landscape, and that dogs were preferable? Such an argument fails to understand that on the Discovery Antarctic expedition (1901–1904), Scott had brought dogs for transportation, but these had prematurely failed during the ‘Farthest South’ journey by Scott, Dr Edward A. Wilson and Lieutenant Ernest Shackleton, forcing the three men to rely on man-hauling to return to base.

Modern scholarship judges the dogs’ failure in hindsight as due to poor feeding; however, at the time this gave an impression of dogs’ unreliability to both Scott and Shackleton. In his 1909 memoir The heart of the Antarctic Shackleton states frankly that ‘[d]ogs had not proved satisfactory on the Barrier surface’ (Shackleton Reference Shackleton2000: 13) and ‘I placed little reliance on dogs’ (Shackleton Reference Shackleton2000: 15). This explains Shackleton's decision to bring ponies in addition to dogs on his 1907–1909 Nimrod expedition.

There were already precedents for the use of Yakut or Yakutian breed ponies (commonly known as ‘Siberian ponies’) in the polar regions. They had been used on the 1894–1897 Jackson-Harmsworth Franz Josef Land [Zemlya Frantsa-Iosifa] expedition, and veteran Albert Armitage recommended them during the Discovery expedition as alternative polar transport. Discovery engineer Reginald Skelton wrote on 3 February 1902, ‘from conversations with Armitage, who was in Franz Josef Land & used them, ponies seem to be very fine draft animals over this sort of snow, Siberian ponies’ (Skelton Reference Skelton2004: 51). Five Siberian ponies had been employed in Anthony Fiala's 1901–1902 Arctic expedition, and 30 ponies on the 1903–1905 Fiala-Ziegler Arctic expedition (Fiala Reference Fiala1907: 9, 19). Shackleton himself wrote, ‘I had seen these ponies in Shanghai, and I had heard of the good work they did on the Jackson-Harmsworth expedition. They are accustomed to hauling heavy loads in a very low temperature, and they are hardy, sure footed, and plucky’ (Shackleton Reference Shackleton2000: 14).

On his Nimrod expedition Shackleton used Manchurian ponies (a regional variation of the Yakutian breed), and they proved more reliable than his dogs. As Scott biographer Ranulph Fiennes observes, ‘The dogs [Shackleton] had brought south were left at base when the group set out for the Pole. . . The four ponies that had survived the winter coped infinitely better than the dogs Shackleton had trained and led on Scott's 1903 Southern Journey’ (Fiennes Reference Fiennes2004: 153).

Bringing only four ponies to haul their equipment, Shackleton's polar party (himself and three companions) reached as far as the glacier he would name the Beardmore (approximately 380 nautical miles from their base at Cape Royds). When the last pony died by falling down a crevasse (Shackleton Reference Shackleton2000: 205), Shackleton's party continued to man haul sledges further up the glacier and onto the polar plateau. Shackleton's team reached a ‘Farthest South’ of 97 nautical miles north of the pole, after which they turned for base, man hauling the entire return journey of 700 nautical miles. Thus we see the pattern of using animal transport for part of the way, then man hauling for the remainder, which would be at least partially employed on Scott's Terra Nova expedition of 1910–1913 (although, unlike Shackleton, Scott planned to employ dogs later on for back-up, and left written orders in October 1911 for dog-teams to come out from base to meet the polar party on their return across the Barrier (Evans Reference Evans1949: 186–188), orders which were unfortunately not followed by Scott's men at base (May Reference May2012)).

Given Shackleton's success using only four ponies, the fact that the German explorer Wilhelm Filchner brought seven Siberian ponies on his 1911–1912 Antarctic expedition (Filchner Reference Filchner and Barr1994: 12, 73), and that the Japanese explorer Nobu Shirase also planned to bring ponies for his 1910–1912 Antarctic expedition, and was only prevented from doing so by his ship's size (Turney Reference Turney2012: 149), it is pure modern hindsight to attack Scott for bringing ponies to Antarctica and for not relying exclusively on dogs. In bringing three forms of transport (ponies, dogs and motor sledges) Scott was working within a tradition of scientific experimentation aiming to cover all eventualities.

However, Scott's use of ponies on his Terra Nova expedition is fraught with misunderstandings and ‘red herrings’ in modern polar literature. They were indisputably of poor-quality: Wilson called them ‘a great string of rotten unsound ponies’ (Seaver Reference Seaver1959: 263) and Scott noted on 13 November 1911, ‘I am anxious about these beasts – very anxious, they are not the ponies they ought to have been’ (Scott Reference Scott1913: 319, italics ours). However, certain modern narratives declare that the purchaser, Cecil Meares (Fig. 1), had been forced by Scott into a job for which he was unqualified. Evidence indicates that Meares had better qualifications for the task than previously thought.

Fig. 1. Cecil Meares (left) and Captain Lawrence Oates in the stables, Cape Evans, 26 May 1911. Photo by Herbert Ponting. Image copyright the National Portrait Gallery, London.

Was Meares unqualified to buy the ponies?

In January 1910 Meares was sent by Scott to the city of Vladivostok in Siberia with the mission of buying both dogs and ponies; Meares’ dogs were strong, but his ponies noticeably less so. Apsley Cherry-Garrard wrote in his expedition memoir The worst journey in the world (1922), ‘It must be confessed at once that some of these ponies were very poor material, and it must be conceded that [Captain Lawrence] Oates who was in charge of them started with a very great handicap’ (Cherry-Garrard Reference Cherry-Garrard1994: 117).

A common argument in polar literature goes that Scott was aware that Meares was unqualified, yet still sent him for this vital mission. In the biographer Roland Huntford's words, ‘someone ignorant of horses did the notoriously difficult business of buying them’ (Huntford Reference Huntford1979: 324, Reference Huntford2002: 309). Other polar historians concur (Preston Reference Preston1997: 113; Smith Reference Smith2002: 99; Wheeler Reference Wheeler2002: 78; Riffenburgh and Cruwys Reference Riffenburgh and Cruwys2004: 27; Mills Reference Mills2008: 136; Limb and Cordingley Reference Limb and Cordingley2009: 115; MacPhee Reference MacPhee2010: 24; Riffenburgh Reference Riffenburgh2011: 12). However, the biographer Fiennes counters this:

[Meares] must have appeared as a godsend [to Scott] for here was a man with years of experience at driving dogs in Siberia, who knew the exact areas where not only the best dogs but also the best ponies were to be purchased. On top of that he knew how to horse-trade in the local language and so was unlikely to be fobbed off with cranky beasts (Fiennes Reference Fiennes2004: 168)

Therefore the question is how Meares presented himself to Scott in January 1910. Dramatist Trevor Griffiths’ screenplay of Huntford's book, The last place on earth, presents Meares as a self-confessed equine ignoramus: ‘I simply wanted you to be aware of the limits of my qualifications. Dogs I know. Horses I don’t. If you tell me to buy horses I will buy them and do the best I can’ (Griffiths Reference Griffiths1986: 72). However, it must be remembered that Griffiths is writing a television drama, not history. There is no primary evidence in archives to indicate any confession of limitations from Meares to Scott in January 1910.

Huntford accuses Scott of conflating canine knowledge with equine knowledge in sending Meares: ‘Scott assumed that anyone who knew about dogs was qualified to buy horses’ (Huntford Reference Huntford1979: 324, Reference Huntford2002: 310). Griffiths, following Huntford, gives his fictionalised Scott the dialogue ‘It's my considered view that a man who knows, really knows, any animal, knows all animals to some extent’ (Griffiths Reference Griffiths1986: 72). However, as Huntford cites no evidence, his presentation of Scott's inner motivation must be considered an unsupported hypothesis. The onus is not on the present writers to ‘find evidence’ that Scott did not think this way. It is self-evident that dogs differ from horses: until Huntford produces the necessary archive evidence to support his statement, we must take it that Scott did not hold such an erroneous belief.

That Meares did possess knowledge of horses can be seen from his Boer war service. On 8 November 1901 Meares joined the 1st Scottish Horse regiment, a cavalry regiment (Scottish Horse, nominal roll), and served with them in South Africa until the war ended in May 1902 (Mills Reference Mills2008: 113–114). After only four months Meares was promoted from trooper to lance-corporal (Mills Reference Mills2008: 114). Since an NCO had to possess the ability to lead his fellow cavalrymen, and make parade-style inspections of his men and horses to make them ready for the officer's inspection, Meares’ swift rise in the Scottish Horse indicates that he was familiar with horses.

In addition to his wartime cavalry experience, Meares, somewhat unusually, was a Russian speaker (his spoken Russian was judged first class by the War Office in 1915 (Meares, RNVR service record)) with proclaimed first-hand understanding of the Russian marketplace: his biographer Leif Mills notes that he ‘dabble[d] in fur trading’ in Russia before 1901 (Mills Reference Mills2008: 113) and that he ‘did some trading in furs’ in Siberia in 1903 (Mills Reference Mills2008: 114). Thus Scott's decision to charge Meares with purchasing the expedition's ponies appears to have been based on Meares’ known background. It would have made perfect sense for Scott to trust a Russian-speaking ex-cavalryman (with first-hand knowledge of trading in Siberia) with the purchase of the ponies.

In the next section we shall examine the differing accounts of the ponies’ purchase. In particular we shall concentrate on the problematic nature of the account which has most commonly been taken as factual: that from the 1911 journal of scientist Frank Debenham.

Who bought the ponies, and where: Manchuria or Siberia?

As there are differing narratives of this purchase, both of the location and of the buyer, this section will assess the various narratives to identify the most likely buyer and location. One story relates that the ponies were purchased in Meares’ absence by a third party, Meares’ friend, in Harbin, Manchuria (King, H.G.R. Reference King1972: 255), a version repeated by some polar writers (Huntford Reference Huntford1979: 325, Reference Huntford2002: 311; Lagerbom Reference Lagerbom1999: 52; Smith Reference Smith2002: 113; Mills Reference Mills2008: 136; Barczewski Reference Barczewski2009: 64; MacPhee Reference MacPhee2010: 25; Knopp Reference Knopp2012: 109). This story appears to derive from media reports in 1910 stating that Meares planned to purchase the ponies ‘in the country round Harbin’ (compare The Times, (London) 15 January 1910: 10). However, no evidence exists that the ponies actually were purchased in Harbin.

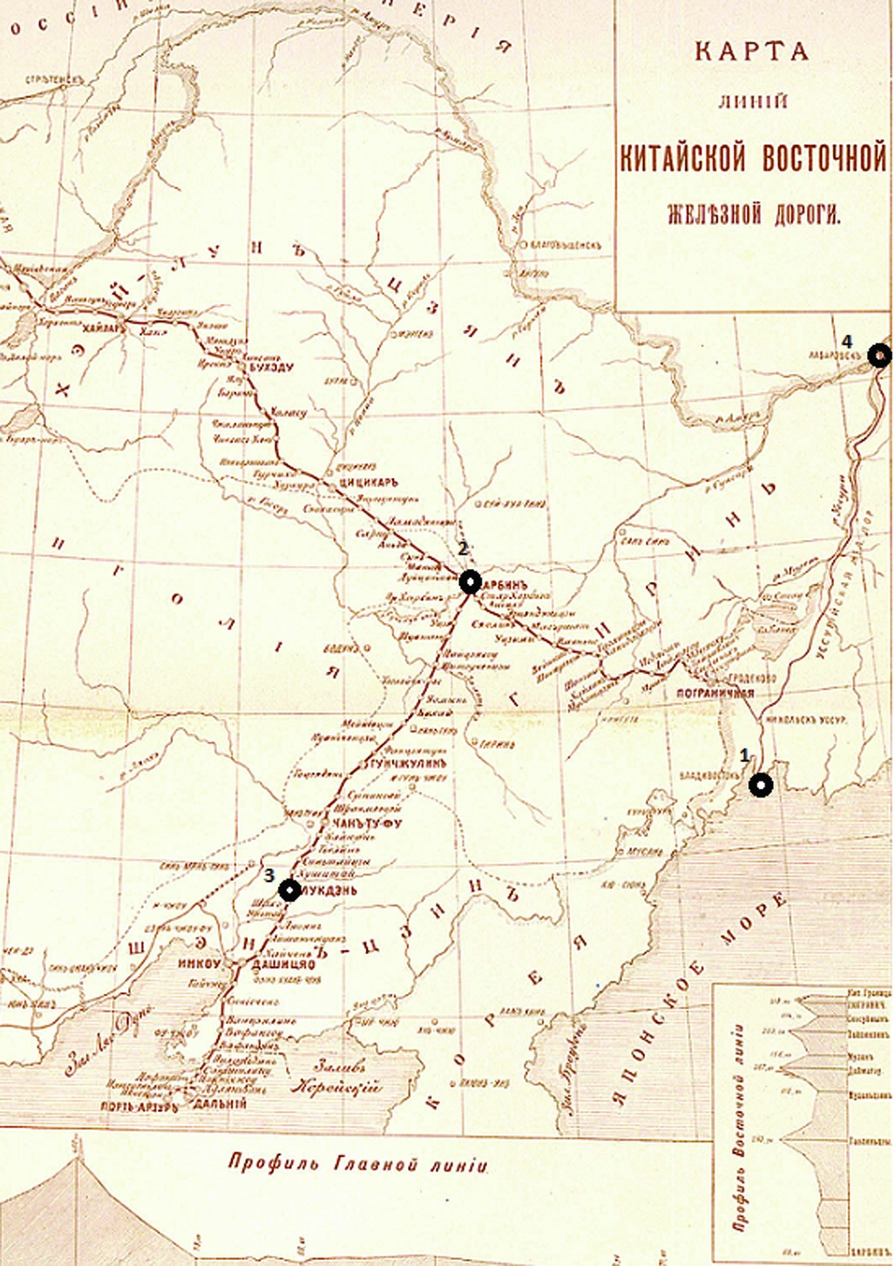

A map of the rail network (Fig. 2), demonstrates that Mukden (the other proposed Manchurian location for the purchase) is not in the region of Harbin. Reaching Mukden entailed travelling a further 347 miles south from Harbin, switching at Chang-Chun to another branch line, the Japanese-owned South Manchurian Railway (Robinson and Yen Reference Robinson and Yen2012: 20). However, it must be emphasised that Frank Debenham's journal entry of 18 June 1911 specifically states that the transaction took place in Mukden, not Harbin. His informant was presumably Meares himself, and Debenham calls the purchase:

Fig. 2. A map of the Chinese Eastern Railway, dated 1900. On this map: Vladivostok (Point 1), Harbin (Point 2: 322 miles northwest of Vladivostok) Mukden (Point 3: 347 miles southwest of Harbin) and Khabarovsk (Point 4: 470 miles north of Vladivostok, on the Trans-Siberian Railway). Nikolaevsk-on-Amur, where Meares purchased his dogs, is located approximately 600 miles northeast of Khabarovsk.

a curious blunder. Capt. Scott, hearing that of Shackleton's ponies the dark ones died and the white ones lived, and in the popular belief that white animals resist cold better, ordered Meares to get only white ones if possible. Meares, who is no judge of horse flesh, got a friend to pick the ponies for him in a fair at Mukden. There were only about 200 to pick from so there was little choice, the white ponies forming about 15–20% of the lot. Anton [Omelchenko] was present at the sale and he says that the seller of the ponies went away with a ‘plenty big smile’ on his face. So I suppose we have been ‘sold a pup’ (Debenham Reference Debenham and Back1992: 109)

Some polar historians (Preston Reference Preston1997: 113; Solomon Reference Solomon2001: 128–129; Raeside Reference Raeside2009: 68) have taken this account as factual, probably because it is supported by the Ukrainian groom Anton Omelchenko, who is quoted by Debenham as having been present at the transaction in Mukden in 1910. However, we must look more closely at Omelchenko's testimony.

As a jockey who had worked with horses since 1893 (King, H.G.R. Reference King1972: 255), Omelchenko would have been used to checking horses closely, to avoid being deceived by ‘ringers’ (substitute horses used to defraud betting systems). He could doubtless observe signs of age and debility. However, Wilson, a zoologist, wrote that ‘several of [the ponies] are as old as the hills’ (King, H.G.R. Reference King1972: 179) and Oates remarked in a letter that the whole batch were ‘very old for a job of this sort’ (Oates Reference Oates1910b; Limb and Cordingley Reference Limb and Cordingley2009: 122). Why, then, did Omelchenko not prevent their purchase?

There are three possible explanations for Omelchenko's declaration that he was present at the purchase. The first is that Omelchenko, despite his 17 years’ equine experience, sincerely confused ancient ponies with sound specimens. The second is that Omelchenko, in giving this account, inadvertently incriminated himself: since he allowed the fraudulent transaction to occur, perhaps he colluded with the horse trader, and passed infirm ponies as sound in order to swindle Meares’ colleague. However, the third explanation is more credible than either of these: namely, that this Mukden incident never happened. We believe that, rather than admit direct responsibility for the purchase when challenged in June 1911, Meares approached Omelchenko and asked him to give eyewitness support to the fiction that, in Meares’ absence, Meares’ ‘friend’ had been swindled in Mukden. It is our hypothesis that Omelchenko told a minor lie to support Meares, the man to whom he owed his job, unaware that his testimony would be recorded by Debenham.

Debenham's account is anomalous, as it is the only source that states explicitly that a third party other than Meares bought the ponies, and that this was because Meares was ‘no judge of horse flesh’. A number of contemporary sources assert that the ponies were in fact purchased by Meares himself, and most of them place the transaction in Siberia, not Manchuria:

[T. Gran, journal entry, 22 February 1911] No, our horses are nothing to boast about: Meares was badly taken in when he bought them in Siberia (Hattersley-Smith Reference Hattersley-Smith1984: 61)

[Oates, letter, 24 October 1911] Meares goes home in the ship he is a very good chap although he did buy all these rotten ponies (Oates Reference Oates1911; Mills Reference Mills2008: 157)

[Oates, journal, 12 November 1911] Meares said he was surprised how well the ponies were going which is rather amusing considering he was responsible for buying the old screws (Limb and Cordingley Reference Limb and Cordingley2009: 177)

[T. Griffith Taylor, With Scott: the silver lining (Reference Taylor1916)] Meares had been collecting dogs and ponies in Manchuria (Taylor Reference Taylor1916: 11)

[E.R.G.R. Evans, South with Scott (1921)] [T]he ponies were collected and brought from up-country in batches. On arrival at [Vladivostok] they were examined by the Government vet., after which Meares and an Australian trainer picked the best, until a score were purchased (Evans Reference Evans1949: 42–43)

[Herbert Ponting, The great white south (1922)] [Meares] took the entire responsibility upon his own shoulders of securing all the transport animals. . . Meares personally found, tried out and purchased the animals that were required (Ponting Reference Ponting1923: 5)

[H.G. Lyons, British (Terra Nova) Antarctic expedition 1910–1913: miscellaneous data (1924)] Those [ponies] used in the Expedition. . . were selected at Vladivostock by C. M. Meares (Lyons Reference Lyons1924: 63).

[W. Bruce, Reminiscences of the Terra Nova in the Antarctic (Reference Bruce1932)] [Meares] took me at once to see the twenty ponies. . . he had collected up country, and with which he was quite pleased (Bruce Reference Bruce1932: 4)

In the light of the disparity between Debenham's journal and these other sources, we must consider what Meares himself is recorded as having stated. In September 1910, Meares gave a media interview in which he makes no reference to any friend, but explicitly claims full responsibility for selecting the ponies in Siberia:

‘I bought the ponies near Vladivostock,’ said Mr. Meares in answer to questions. ‘Word was sent out as to what was wanted, and scores were brought in from the country - some from as far in as 300 miles west of Vladivostock - for me to inspect and try. In selecting them my main consideration was the work they were used to, so as to get animals accustomed in a way to what we are going to use them for. They are all Siberian ponies, except one, and that's a Manchurian, like Shackleton had. Having spent a long time in Siberia, I know the types well, and I prefer the Siberian pony. He is more used to colder weather, is bigger and stronger, and is, I should say, generally better suited to our work than the Manchurian. All the ponies are aged, and the average price I gave for them was about £10’ (Sydney Morning Herald 10 September 1910: 15)

Another interview, dated ‘Wellington, Sept 14’, appeared in the Wanganui Chronicle on 15 September. Though possibly a paraphrase of the previous interview, it is cited below:

‘The ponies came into Vladivostock from miles around for my inspection,’ Mr Meares said. ‘Some of them came from places 300 miles away from port. I wished to see what they could do in the way of work. I have spent a long time in Siberia and other parts of the Russian Empire, and I know the pony of the country pretty well. I prefer the Siberian to the Manchurian, because he is used to colder weather, is bigger and stronger, and, generally speaking, is better for our purpose than the Manchurian.’ (Wanganui Chronicle (Wanganui, New Zealand) 15 September 1910: 8)

Another interview is reported in a Tasmanian newspaper:

‘These ponies,’ Mr. Meares explained, ‘are chosen because they have been accustomed to work in the ice and snow in Siberia. They came 300 miles to Vladivostock from Northern Siberia, and cost from £5 to £10 a piece. Shackleton secured Manchurian ponies for his expedition, but my experience goes to show that these ponies will stand the rigor of an Antarctic winter better than the others; besides they are accustomed to the work for which we want them’ (The Mercury (Hobart, Tasmania) 16 September 1910: 7)

The charge against Scott for the past few decades has been that Meares was out of his depth. Yet in September 1910 Meares stated to the media that he had ‘experience’ of such matters, claimed familiarity with the breeds and demonstrated his equine knowledge with the specific equine technical term ‘aged’ (indicating a pony is nine years or older). Meares here comes across as a confident and capable professional.

For too long Debenham's journal entry, relating the story of Meares’ ‘friend’, has been taken as primary evidence. In fact it is secondary evidence: it is Debenham's innocent repetition of an unlikely tale related to him a year after the ponies’ purchase. There is far more evidence (including Meares’ own testimony) to indicate that Meares himself bought these Siberian ponies in Siberia. Indeed, when one considers the logistics of a purchase in Manchuria (fluency in Manchu or Mandarin Chinese, for negotiations; the problem of trusting an outsider with a large amount of cash; the costs of travel, meals, accommodation, stabling and the customs duties levied upon horses bought in the Chinese Empire and transported across the border into Russia) one can see that Siberia is the most credible location, and Meares the person most likely to have made the purchase.

Cherry-Garrard observed sadly in 1922, ‘[t]here was little [Oates] didn't know about horses, and the pity is that he did not choose our ponies for us in Siberia: we should have had a very different lot’ (Cherry-Garrard Reference Cherry-Garrard1994: 222). From this comment a modern myth has arisen that Oates actively expected to go to Vladivostok in 1910, and that it was somehow Scott's fault that he did not go. The next section demonstrates that, in reality, Scott specifically requested Oates to travel to Vladivostok to assist Meares with the ponies, but Oates refused.

Did Oates expect to buy the ponies himself?

The earliest source we can find for the argument that Oates expected to go to Vladivostok to assist Meares is Huntford, who states of Meares’ purchase: ‘Oates. . . had joined the expedition as a horse expert and so presumed that he would have a hand in their choice’ (Huntford Reference Huntford1979: 324, Reference Huntford2002: 310). Oates biographers Sue Limb and Patrick Cordingley concur (‘[Oates] must have wondered that he was not sent to buy the horses, but he accepted Scott's decision’ (Limb and Cordingley Reference Limb and Cordingley2009: 116)), as does Michael Smith (‘Oates, the expert, fully expected to be sent to the Far East to buy the hardened Siberian or Manchurian ponies on which so much rested’ (Smith Reference Smith2002: 99)).

However, no contemporary evidence is cited by any secondary historian to support the statement that Oates wanted to buy the ponies. All that is stated is the unsubstantiated hypothesis that Oates, as the horse specialist, would have expected to assist with the purchase. In fact, as Fiennes explains, the immediate context must be considered: ‘[Oates] appeared on the scene far too late to help Meares select ponies in Manchuria, since he only obtained leave from his cavalry regiment in India in March 1910 and reached Terra Nova in London in May, three weeks before her voyage began’ (Fiennes Reference Fiennes2004: 168). Since Oates was not granted official leave to join the Terra Nova expedition until March 1910 (Limb and Cordingley Reference Limb and Cordingley2009: 108), he could not have been factored into Scott's expedition plans back in January 1910.

On 18 March 1910, Meares wrote to his father from Nikolievsk (now Nikolaevsk-on-Amur), 1042 miles from Vladivostok, where he was purchasing the dogs: ‘The road here will soon be broken so I will not be able to send or receive any more letters till the spring. I expect to be back in Vladivostock by the middle of June where I will collect the ponies’ (Meares 1910; Mills Reference Mills2008: 135).

This means that even if Oates had travelled to Vladivostok on his leave date of 26 March, he could not have contacted Meares. By April 1910 Meares was 1042 miles from Vladivostok. Had he travelled there immediately upon getting leave, Oates would have had to wait in India for around 3 weeks for Russian and Chinese visas to be approved, then upon arriving in Vladivostok would had to wait there for at least 3 weeks for Meares’ return; he would also have lost his opportunity to revisit Britain, purchase equipment and see his family. It is therefore unreasonable to suggest that Oates should have travelled immediately to Vladivostok from India.

However, there was a clear opportunity for Oates to have gone out to Siberia to assist Meares after returning to Britain. Far from Scott's preventing Oates from joining Meares in Siberia, there is contemporary evidence that Scott specifically asked Oates to travel there to assist Meares. However, Oates refused, so Scott asked his brother-in-law Wilfrid Bruce to go instead. As Bruce wrote in 1932:

I arrived in London on June 13 [1910], and went at once to see Scott. . . [Scott] went on to explain to me that he had tried to stop me on the way home [Bruce had been travelling from China to London on the Trans-Siberian railway], as Cecil Meares, who had been sent to Siberia to collect ponies and dogs for the Expedition, had asked for another man to assist him to transport them from Vladivostok to New Zealand. Captain Lawrence Oates was eventually to take charge of the ponies, and Scott had intended to send him out to Meares. But Oates very much wanted to sail all the way out in the Terra Nova, so Scott asked me if I would mind taking his place (Bruce Reference Bruce1932: 3–4, italics ours)

A letter from expedition member Lieutenant Henry R. Bowers to his mother, dated 22 June 1910, independently corroborates Bruce: ‘Oates wanted to sail in the ship & not go to Siberia. Bruce was willing to go to Vladivostok at his own expense & assist Meares, so the arrangement was settled’ (Bowers Reference Bowers1910, italics ours; Strathie Reference Strathie2012: 75, 205 (endnote 8)).

It should be understood that Oates was not expected to help purchase the ponies. All Bruce states is that Meares had asked for assistance with the animals’ transportation from Vladivostok to New Zealand. Bruce and Oates were the only possible candidates for this task, as the cash-strapped expedition could not fund a third party and both Bruce and Oates could afford to pay their own way. Oates, of the landed gentry, had already donated £1000 (£89,070 in 2013 terms (MeasuringWorth website)) to the expedition, whilst Bruce, according to Bowers’ 22 June letter, ‘had recently made £30,000 in the Rubber Boom’ (Bowers Reference Bowers1910), equivalent to over £2.6 million in 2013 terms (MeasuringWorth website). It was Bruce who helped Meares transport the animals from Vladivostok on 26 July (via Kobe, Japan) to arrive in Sydney, Australia on 9 September: from there they reached Lyttelton, New Zealand on 15 September (Bruce Reference Bruce1932: 4–5).

However, had Oates agreed to Scott's request, he would have been preferable to Bruce. Unlike Bruce, Oates could assess ponies’ defects, as he describes doing so for an equitation course in 1906: ‘They gave me a weed of a troop horse and asked me to pick out its faults’ (Limb and Cordingley Reference Limb and Cordingley2009: 65).

The train journey from London to Vladivostok took ‘thirteen days’ (Bruce Reference Bruce1932: 4) and we know from Bruce's account that by 13 June Scott had already asked Oates to go to Siberia, and had been refused (Bruce Reference Bruce1932: 3). Oates was in Britain until 15 June: on that date Terra Nova sailed from Cardiff on her voyage south. Had Oates agreed to Scott's proposal, he would have needed to wait in Britain a further 3 weeks or so for Russian and German visas, but could have left on the Trans-Siberian railway during late June or the first week of July, to arrive in Vladivostok sometime around 13–20 July. By this time the substandard ponies would probably already have been purchased, but in the period before the departure from Vladivostok Oates would have spotted the problems with these ponies and might have been able to pay for replacements from his own purse.

Even if buying fresh ponies proved impossible, Oates could have sent a telegram to reach Scott in South Africa in August 1910, warning him that many of Meares’ ponies were unfit for purpose; early notice would have given Scott an extra 12 weeks to make alternative transportation arrangements. Objectively, it would have been preferable for Oates to travel to Siberia rather than Bruce.

However, Oates instead chose to stay with the ship from Britain to New Zealand. He had a deeply personal reason for this: the stop-over in Madeira during 23–27 June allowed him to visit his father's grave (Limb and Cordingley Reference Limb and Cordingley2009: 119), a rare opportunity he would have forfeited had he gone to Siberia. The time on board Terra Nova also allowed him to make friends and acquire sailing skills for his free time on his yacht Saunterer, purchased in July 1905 (Limb and Cordingley Reference Limb and Cordingley2009: 61–62). As he wrote to a friend during the voyage, ‘I am signed on as midshipman. . . I enjoy it immensely and am learning a lot of seamanship’ (Oates Reference Oates1910a). Oates therefore had far greater motivation to stay on the Terra Nova than leave for Siberia.

The myth that Oates actively wanted to assist with the ponies’ purchase appears to have originated in an unsubstantiated 1979 presumption by Huntford (‘Oates. . . presumed that he would have a hand in [the ponies’] choice’ (Huntford Reference Huntford1979: 324, Reference Huntford2002: 310)). Huntford consulted Bruce's 1932 article during research (Huntford Reference Huntford1979: 597 (endnote 19)) but evidently overlooked Bruce's observation that Oates had refused Scott's request. In his screenplay, Griffiths’ fictionalised Oates is even given the dialogue, ‘I offered to go along and choose the ponies myself. Was there some particular reason I wasn't asked to?’ (Griffiths Reference Griffiths1986: 95, italics ours). The archive evidence tells a very different story.

One final strand in the myth must be addressed. In 1913 Lieutenant E.R.G.R. Evans wrote an article on Oates stating that, back in 1910:

Lieutenant Campbell and [Evans himself] went to Captain Scott and asked if we might enrol Oates as a midshipman and keep him on the Terra Nova, rather than let him rush across Siberia to help Meares select and purchase ponies and dogs. Captain Scott consented to our acquisition of this very able-bodied ‘seaman’, and on May 31st, 1910, Captain L.E.G. Oates was signed on as a midshipman in the yacht Terra Nova (Evans Reference Evans1913: 616)

This 1913 article appears to be Evans’ gentlemanly post-expedition claim of personal responsibility for Oates’ not travelling to Siberia. However, it must be understood that Oates was not forced to remain on the ship against his will. Just because he had been made a midshipman on 31 May did not mean that he was required to stay on the ship after that date: he was entirely able to leave the ship to fulfil duties on land should the expedition leader ask him to do so. Indeed, Evans’ 1913 article states that Oates had originally applied ‘to serve on the Expedition in any capacity’ (Evans Reference Evans1913: 615, italics ours), hence it was perfectly reasonable for Scott to ask Oates in June to change his plans and go to Siberia rather than stay on the ship. However, since Oates’ £1000 contribution had been accepted, Oates was now irrevocably part of the expedition: Scott could not have threatened him with dismissal for noncompliance, or forced him to do anything he did not want to do. Therefore using Evans’ 1913 article as ‘evidence’ that Oates was somehow prevented from going to Siberia is erroneous. Had Oates independently judged in June 1910 that his proper function was to travel to Siberia to assist Meares, then he would have done so, and with Scott's full support. However, Bruce's and Bowers’ independent accounts both state that Oates himself rejected Scott's request to travel to Siberia. Cherry-Garrard charitably avoided placing blame in 1922 by stating neutrally that it was ‘a pity’ that Oates ‘did not choose’ the ponies in Siberia: however, had it only been stated explicitly in a widely-read expedition narrative that Oates refused Scott's request to go to Siberia, then the modern myth that Oates actively wished to go to Siberia, and that it was somehow Scott's fault that he did not go, would never have had a chance to take root.

In the next section we shall assess the hypothesis that Meares was hindered by the supposed order to buy white ponies only.

Did Scott insist on white ponies only?

In polar literature there has been a conception that Scott insisted that Meares should purchase white ponies. This notion (implicitly arguing that Meares was forced into buying decrepit specimens purely for their colour) has practically hardened into an axiom of polar literature (Huxley Reference Huxley1977: 233; Huntford Reference Huntford1979: 325, Reference Huntford2002: 311; Preston Reference Preston1997: 113, 217; King, P. Reference King1999: 21; Lagerbom Reference Lagerbom1999: 52; Smith Reference Smith2002: 113; Riffenburgh and Cruwys Reference Riffenburgh and Cruwys2004: 26; Barczewski Reference Barczewski2009: 64; Mills Reference Mills2008: 135–136; Limb and Cordingley Reference Limb and Cordingley2009: 115; Raeside Reference Raeside2009: 66; MacPhee Reference MacPhee2010: 25; Ryan 2009: 353; Hooper Reference Hooper2011: 45; Knopp Reference Knopp2012: 109).

The argument that Scott ‘insisted’ on white ponies is a broad exaggeration of events. There is evidence for a recommendation of white ponies in Debenham's and Wilson's journals in 1911, and a September 1910 interview in which Bruce asserts that the white ponies ‘had been specially selected for that reason, as Sir Ernest Shackleton had found that the white ponies. . . had proved the best for work and ability to withstand the privations of the Antarctic’ (The Press (Canterbury, New Zealand) 16 September 1910: 8).

However, in stating that Scott had forced Meares to buy white ponies only, modern commentators have disregarded the following important qualifier in both Debenham's and Wilson's journals:

[Debenham] Capt. Scott. . . ordered Meares to get only white ones if possible (Debenham Reference Debenham and Back1992: 109)

[Wilson] He was. . . told to get white ones if possible (King, H.G.R. Reference King1972: 179)

The caveat ‘if possible’ means that Meares was not limited by a stringent remit. Scott's original written orders have not survived, but any statement from Scott on the preferred colour should have been taken as a recommendation, not as an essential precondition to which all other concerns were secondary.

Wilson discusses the issue in his journal entry for 15 October 1911:

I am afraid the string of ponies which we have were not chosen under the best possible conditions at Vladivostok. The chooser was not very knowledgeable about horses and trusted too much to a dealer and a vet. He was rather handicapped also by being told to get white ones if possible, which must have reduced his selection enormously. This preference for white horses resulted from the fact that in Shackleton's lot down here the white ones survived longest and seemed hardiest, but I doubt whether there was enough in it to warrant the cutting down of a very much larger selection in the Vladivostok market (King, H.G.R. Reference King1972: 179, italics ours)

Most striking here is Wilson's quiet observation that even if ‘the chooser’ had considered himself ‘handicapped’ by ‘being told to get white ones’, the recommendation of white ponies should not have warranted the ‘cutting down’ of the selection. The colour issue should not have outweighed the need for healthy ponies.

The story that Meares believed he had to obey orders to buy ‘white ponies’, regardless of their strength, would only be credible if Meares were a dull-witted character terrified of disobeying his superiors. However, evidence abounds of Meares’ independence and resourcefulness. He had already spent much of his life travelling in remote areas, and he had been engaged in British military intelligence as an ‘observer’ (an intelligence agent) during the 1900 Chinese ‘Boxer Rebellion’ and the Russo-Japanese conflict of 1904–1905. Scott biographer David Crane cites an interview in which Meares hints at his intelligence work (Crane Reference Crane2006: 433). Objective factual evidence exists in Meares’ World War I record: in September 1914 his Army rank on active service was Second Lieutenant (Meares, medals card), yet with his March 1915 transfer to the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) he rose three whole grades to Lieutenant-Commander in the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve (equivalent to an Army Major), and from March 1915–January 1917 he was Intelligence and Transport Officer for the 4th Wing of the RNAS in France (Meares, Conduct certificate, 1917: Mills Reference Mills2008: 175). This accelerated promotion to an important role in military intelligence can only be explained by Meares’ having prior experience of intelligence work.

Judging from his background, Meares was used to improvising in difficult and even dangerous situations, and would have known that men's lives could depend on their transportation animals. Therefore, had the majority of the white ponies for sale been unhealthy, the next logical move should have been, as Wilson hints, to purchase healthy ponies of other colours and explain to Scott that these specimens, whilst not white, were the strongest available. As an ex-cavalryman, Meares had sufficient authority to challenge and adapt the initial remit. Indeed, in his media interviews he states that he independently selected Siberian ponies rather than the Manchurians used to such good effect by Shackleton: ‘I know the types well, and I prefer the Siberian pony. He is. . . better suited to our work than the Manchurian‘ (Sydney Morning Herald 10 September 1910: 15, italics ours).

That Meares evidently felt able to alter his remit concerning the ponies’ type testifies that he was not a dull-witted character who would follow the letter of the law rather than the spirit. Meares knew he could use his independent judgement as circumstances dictated: therefore he should have purchased the strongest available ponies regardless of colour. If Meares had bought strong ponies capable of hauling loads without requiring Oates’ near-constant support, no-one would have cared what colour their coats were. We do not yet know why Meares bought weak ponies, but he must be held responsible for buying them when he demonstrably had the initiative, and opportunities, to buy healthy ones.

In the next section we shall examine another myth (that Meares was a worthy judge of Scott's transportation plans), and propose possible reasons why Meares purchased substandard ponies.

‘Scott ought to buy a shilling book about transport’?

One story in modern accounts has Meares audibly contemptuous of Scott's transport arrangements: ‘At the time, he told Oates that “Scott ought to buy a shilling book about transport”’ (Huntford Reference Huntford1979: 396, Reference Huntford2002: 379). This story has been repeated in various expedition narratives, factual and fictional (Griffiths Reference Griffiths1986: 192; Bainbridge Reference Bainbridge1991: 87; Lagerbom Reference Lagerbom1999: 112; Smith Reference Smith2002: 159; Spufford Reference Spufford2003: 330; Fiennes Reference Fiennes2004: 242; Mills Reference Mills2008: 152; Limb and Cordingley Reference Limb and Cordingley2009: 160; Ryan 2009: 359). Unfortunately Huntford has not yet provided an archive source for Meares’ alleged ‘shilling book on transport’ remark: until a source is provided, this story must be taken as unsubstantiated.

Objectively, Meares had no authority to criticise, as he had contributed significantly to Scott's transportation problems by buying substandard ponies. Evidence abounds of their poor condition: one of the original 20 ponies was infected with glanders and had to be left behind (Bruce Reference Bruce1932: 4); Oates judged 4 of the remaining 19 ponies to be ‘unsound’ in a private letter of November 1910 (Oates Reference Oates1910b); 3 of the 8 ponies on the depot-laying trip of early 1911 were too weak to reach 80° South and had to be sent prematurely back to base, two dying of exhaustion en route; out of the 10 ponies remaining by June 1911, Debenham commented that ‘only 3 or 4 are at all decent’ (Debenham Reference Debenham and Back1992: 109).

Scott wanted Meares to purchase healthy ponies. This is evident from a public speech Scott gave in May 1910, in which he states:

a member of the expedition, Mr Meares, left London several months ago to proceed to Siberia to collect the twenty ponies and thirty dogs which I have decided to take. I have received most satisfactory accounts of his progress, and feel confident that the animals that he will ship from Vladivostock via Kobe and Sydney to our base, will be as good as it is possible to obtain for our purposes (Scott Reference Scott1910: 13).

Not only did Scott expect these animals to be of good quality, but Scott's mention of the ‘accounts of his progress’ indicates that Meares could communicate with Scott in case of emergency. Indeed, Bruce confirms that Meares had been informed of Bruce's arrival in advance: ‘Meares met me in the train when I arrived at Vladivostok on the 22nd’ (Bruce Reference Bruce1932: 4).

Since Meares had access to funds, equine knowledge, contact with the expedition and the intelligence and initiative to buy healthy ponies, we have to ask why he purchased substandard specimens. An incident later in Bruce's narrative may afford some explanation. By the time the ship reached Kobe on 4 August 1910 Meares had announced to Bruce that he had run out of money altogether, compelling Bruce to provide money to fund the rest of the sea voyage to New Zealand: ‘By this time, Meares had emptied his purse, but I was well known here and had no difficulty in obtaining the necessary money to carry us on’ (Bruce Reference Bruce1932: 4). It is strange that Meares only announced this problem mid-voyage, forcing Bruce to find the necessary funds himself. Why had Meares run out of money? Meares does not state that he had been the victim of theft; the evidence indicates that he had not visited Manchuria (as announced in The Times) but had instead stayed in Siberia, which in theory should have given him a surplus of funds. Moreover, Meares (who had previously worked as both a trader and intelligence agent) should have had the foresight to plan his budget and alert the expedition to any problems ahead of time, enabling Bruce to bring funds with him from Britain. A cynic might suspect that, with this sudden announcement of an ‘empty purse’ after Bruce's arrival, Meares took advantage of his new companion's wealth and good nature. Even if we judge charitably that Meares’ unexpected poverty was a wholly honest mistake, his failure to budget for the animals’ transportation could have resulted in his travelling no farther than Kobe, with ruinous consequences for the British expedition: his serious error here hence demonstrates poor management of his funds.

Alternatively, perhaps Meares was so focused on purchasing strong sledge-dogs that he considered the ponies unimportant. Meares wrote to his father on 18 March 1910, ‘I have been kept very busy collecting dogs, trying teams and picking out one or two dogs and making up a team and trying it on a run of 100 miles and throwing out the dogs which do not come up to the mark and collecting others’ (Meares Reference Meares and Meares1910; Mills Reference Mills2008: 134). Meares clearly did not test the ponies so stringently. Evidence that Meares did not consider the ponies’ fitness a high priority lies in an interview of September 1910:

‘We will use these ponies,’ Mr Meares said, ‘to convey camp equipment and stores to the various depots. They will take no part in the dash to the Pole. That is where the dogs come in’ (The Mercury (Hobart, Tasmania) 16 September 1910: 7)

Meares’ emphasis to the media on the ponies’ comparatively minor role may indicate his independent assumption that, because these ponies would ‘take no part in the dash to the Pole’, their strength did not matter.

When Meares told the media in 1910 that the polar dash was ‘where the dogs come in’, he, as chief dog-driver, may have planned on being one of the first men at the South Pole. Why, then, did Scott not take his dogs all the way to the Pole as originally planned? The available evidence suggests that Scott changed his mind about taking dogs the full distance after a near-fatal accident of 21 February 1911, when Meares’ dog-team broke through a snow-lid and plunged into a crevasse. Meares and Scott prevented the sledge from following the harnessed dogs into the abyss, but Scott wrote, ‘If the sledge had gone down Meares and I must have been badly injured, if not killed outright’ (Scott Reference Scott1913: 126). Cherry-Garrard wrote that ‘Scott told Meares to go down and get the dogs [in the crevasse]. Meares refused’ (Cherry-Garrard Reference Cherry–Garrard1914: 125; Fiennes Reference Fiennes2004: 214). Eventually Scott had himself lowered by rope 65 feet into the crevasse to retrieve the last two animals (Scott Reference Scott1913: 125–126). The fact that this dog-team came so close to disaster, and that his chief dog-driver showed himself unwilling to retrieve his animals from a crevasse, may have decided Scott not to drive dogs up the Beardmore Glacier (already known from Shackleton's 1909 account to be ‘over 130 miles of crevassed ice’ (Shackleton Reference Shackleton2000: 219)). Cherry-Garrard wrote that ‘Up to this day Scott had been talking to Meares of how dogs would go to the Pole. After this, I never heard him say that’ (Cherry–Garrard Reference Cherry–Garrard1914: 125; Fiennes Reference Fiennes2004: 214).

There is one final hypothesis for why Meares purchased substandard Siberian ponies, and this concerns his decision to travel to the extremely remote port of Nikolaevsk-on-Amur. This involved Meares’ leaving the Trans-Siberian railway at the station of Khabarovsk (see Fig. 2) and taking a journey by sledge of approximately 600 miles northeast over the frozen interior to Nikolaevsk (Huxley Reference Huxley1977: 189), and once the dogs were purchased these were transported by sea from Nikolaevsk to Vladivostok, a journey of over 1000 miles on ‘a Russian Naval destroyer’ (Bruce Reference Bruce1932: 4). Why did Meares go so far for dog-testing and buying when he could have more conveniently done this in the Vladivostok region, or paused briefly to buy dogs in Khabarovsk and then brought them on by train to Vladivostok? It would appear that Meares had a reason to make a detour of over 1600 miles to visit Nikolaevsk beyond the purchase of dogs.

One theory, suggested by the Editor of this journal (Ian R. Stone, private correspondence, 17 November 2014) is that Meares may have been working as an intelligence agent during this period. His destination, Nikolaevsk in the Amur River region, was a politically-sensitive area in which the Japanese held a particular interest (they would go on to occupy this area immediately after World War I). Stone also points out that the British government would have been interested in why the Russians and Japanese, enemies in 1905, were on better terms by 1910 (Stone, private correspondence, 6 December 2014) and Meares, having been present at the Russo-Japanese battle at Mukden in 1905 (Mills Reference Mills2008: 116), would have been a good candidate to gather information on this. The announcement in the media that Meares was in Siberia purely to purchase animals for Scott's expedition would hence have been an effective ‘cover story’. Interestingly, a closer look at Meares’ proposed itinerary in The Times report of 15 January 1910 reveals an unrealistic list of destinations (Moscow, Vladivostok, the Amur, Yakutsk, Okhotsk, the Verkhoiansk Mountains, Harbin) impossible to cover within the time allotted: ultimately Meares visited only the first three of these during 1910. The publication of this list in the media suggests that Meares wanted to obfuscate his true destination, the Amur region, by placing it within a mass of extraneous detail. Such efforts at misdirection would have been unnecessary for a mere dog-buying trip.

This theory of clandestine intelligence work is at present not substantiated by direct evidence: however, it provides an explanation for Meares’ otherwise puzzling journey to such a remote location, and his sledge-journeys of ‘100 miles’ into the surrounding areas. If Meares were using the purchase of expedition animals as ‘cover’ for British intelligence work in Siberia, Scott would have complied with this (having worked as an Assistant Director in the Admiralty's Naval Intelligence Division for seven months in 1906–1907 (Lewis and May Reference Lewis and May2013: 9), Scott had personal knowledge of intelligence operations). This hypothesis is offered within this article with regard to Meares’ possible priorities during this period: if he had been engaged in intelligence work as well as holding a personal interest in the dogs’ success, he might not have paid sufficient attention to the ponies’ strength.

We will probably never know for sure what was in Meares’ mind during the ponies’ purchase: he seems to have left no documents for guidance. We must focus instead on the consequences of his purchase. These weak ponies failed even to fulfil Meares’ stated basic objective of ‘convey[ing] camp equipment and stores to the various depots’ in early 1911. During the depot-laying of 25 January–6 March 1911 three out of the eight ponies were so weak that they could not be guaranteed to reach the planned destination of 80° South and return safely. Since Scott needed his animals to survive for the polar trek in November, and had already stated in his journal on 9 January 1911, ‘We can't afford to lose animals of any sort’ (Scott Reference Scott1913: 75), Scott ordered One Ton depot to be built at 79°29’S, roughly 30 miles short of expectations, before turning back to base.

Placing the depot 30 miles short would have unfortunate consequences: on their return from the pole Scott, Wilson and Bowers were too weak to reach the depot, and died in their tent in late March at approximately 79°40’S, around 11 miles south of the depot's location at 79°29’S. When one checks the marching-tables (Scott Reference Scott1913: 441–442), one can see that had the depot been placed at 80° South as originally envisaged, the polar party would have been able to pick up food and fuel around 15–17 March. Though Oates could not have been saved without dog-teams to transport him, the other three men could hypothetically have recovered some strength from fresh supplies. Whether they could have marched the final 149 miles to Hut Point unaided is a matter for conjecture: however, it must be stressed that Scott never intended for the polar party to walk that distance unaided, as he had left orders for the dog teams to travel far enough south to meet the polar party on the Barrier in March 1912 (Evans Reference Evans1949: 186–188; May Reference May2012)).

In addition to sabotaging the depot-laying, Meares’ ancient ponies sabotaged the polar journey itself. On 1 March 1911, during the depot journey, Scott observed of the ponies: ‘it is certain they would lose condition badly if caught in [a blizzard], and we cannot afford to lose condition at the beginning of a journey. It makes a late start necessary for next year’ (Scott Reference Scott1913: 133, italics Scott’s). With healthier ponies, Scott could have attempted an earlier start: with these ponies he had to delay the polar journey's departure until 1 November 1911, when temperatures were sufficiently warm. This later start meant that the polar party was still out on the Barrier in March 1912, when temperatures plummeted dramatically.

Indeed, the botched purchase may have prompted Meares’ premature departure from the expedition in 1912 (a move which posed further difficulties, as it necessitated the surgeon E.L. Atkinson, and later Cherry-Garrard, taking charge of the dog-teams). Given the possibility that during the following year the remaining expedition members (including Tryggve Gran, who had been given the ‘Siberia’ story, and Debenham, who had been given the anomalous ‘Mukden’ story) would have compared notes on the ponies’ purchase, one can see why Meares would have preferred not to remain in Antarctica until 1913. In many ways, then, Meares’ provision of poor-quality ponies in 1910 contributed to the expedition's fatal denouement.

Conclusion

This article's conclusions are as follows:

-

1) A myth has arisen that Meares was unqualified to purchase the ponies and reluctant to do so. No archive evidence exists to show Meares’ reluctance. On paper, Meares was an ideal candidate: his previous cavalry, espionage and trading experience, independent nature and confident manner would have all indicated to Scott that the task was safe in his hands.

-

2) Another myth, recorded in Debenham's journal in June 1911, asserts that Meares did not buy the ponies himself, but that a third party did so in Mukden, Manchuria, in a transaction witnessed by Omelchenko. It is not credible that the purchase of Siberian ponies would have necessitated a trip to Manchuria: it appears that in June 1911 Meares was using Omelchenko to help disseminate misinformation. In September 1910 Meares gave confident media interviews stating that he himself purchased the ponies in Siberia.

-

3) Some have excused Meares by arguing that Meares’ options were limited by Scott's insistence on white ponies. The evidence indicates that, whilst white ponies were recommended, Meares knew he had the freedom to change his remit if circumstances dictated (and demonstrated this freedom in choosing Siberian ponies over Manchurian). Meares therefore should have placed priority on the ponies’ health and strength over their colour.

-

4) Finally, a modern myth asserts that Oates actively wished to go to Siberia to purchase the ponies, and that it was Scott's fault that he did not go. This unsubstantiated myth is directly contradicted by the fact that Oates had only a slender chance of purchasing the ponies (due to delays caused by visa applications and travel) and also by Bruce's and Bowers’ independent testimonies, which both demonstrate that in reality Scott did request Oates to go to Siberia in 1910 to assist Meares with the ponies’ transportation, and that Oates refused Scott's request, preferring instead to stay on board Terra Nova.

The most charitable interpretation for Meares’ botched purchase is that Meares was genuinely swindled by a dishonest horse professional, and that for some reason he did not alert the expedition after having discovered that he had been swindled, but instead kept silent. Alternatively, Meares may not have made the effort necessary to ensure the ponies were suitable, or he may have deliberately chosen to purchase specimens that he knew were not the strongest available. Either way, Meares’ failure cannot be considered Scott’s fault.

It would be uncharitable for present commentators to condemn Scott harshly for ‘misjudgement’ of Meares’ character, because to do so would be to condemn the numerous polar historians (operating with the hindsight unavailable to Scott) who have also given trusting credence to Meares. Huntford and his dramatist Griffiths, for example, presented Meares as blameless, and, to the best of our knowledge, of polar historians writing previous to 2014 only Fiennes has made any criticism of Meares, noting Cherry-Garrard’s private criticisms and labelling Meares’ unpleasant comments a ‘malignant tumour’ (Fiennes Reference Fiennes2004: 242, 361). In 2014 it was revealed that, in January 1912, Meares deliberately chose not to restock One Ton depot with supplies, even though this restocking was necessary for the dog-teams’ ‘third journey’ to meet the polar party. Meares subsequently disseminated misinformation to cover for his refusal (May and Airriess Reference May and Airriess2014). The fact that it took over a century for the issue of Meares’ trustworthiness to emerge in scholarly discussion demonstrates how effectively Meares could project an amiable facade.

In conclusion, we hope that Meares’ responsibility for the purchase of poor-quality ponies (and resulting sabotage of expedition transport) will be given due weight in future reassessments of the expedition. When the present article is placed alongside the previous assessment by Karen May and Sarah Airriess (May and Airriess Reference May and Airriess2014) of Meares’ refusal in January 1912 to restock One Ton depot, and the serious consequences of his refusal, one may more clearly see Meares’ role in the loss of four lives in the Terra Nova expedition's polar party.

Acknowledgements

Our thanks to Professor Grahame Budd, Professor Pat Quilty and one other referee for Polar Record; Jonathan Hopkins (www.cavalrytales.co.uk); ‘Trove’ website, National Library of Australia (www.trove.au); ‘PapersPast’ website, National Library of New Zealand (paperspast.natlib.govt.nz); the Scott family for permission to quote from R.F. Scott's writing; the Wilson family, for E.A. Wilson's writings; the Scott Polar Research Institute, Cambridge, and archivist Naomi Boneham for permission to quote from the correspondence of H.R. Bowers; to Hugh Turner, for permission to quote from Apsley Cherry-Garrard's journals; excerpts from The worst journey in the world by Apsley Cherry-Garrard appear by permission of the Scott Polar Research Institute, University of Cambridge. We must also acknowledge Philip E. Robinson and Vasilis Opsimos of the British Society of Russian Philately (BSRP), for kind assistance with the Chinese Eastern Railway/South Manchurian Railway networks; Dr Lorne Hammond and the British Columbia Archives in the Royal British Columbia Museum, Victoria, BC, Canada; Maureen Lewis; Dr Peter May. Thanks also to the National Portrait Gallery for permission to reproduce the photograph of Meares and Oates.