William Lashly was born 150 years ago on Christmas day 1867. He is remembered by Antarctic historians primarily for his remarkable strength and courage in saving the life of Lieutenant E.R.G.R. Evans on Captain Scott's last Antarctic expedition and by polar scientists for the fossil-rich Antarctic mountain range which bears his name. Yet Lashly the man remains a bit of an enigma. Like many of the ordinary seamen who participated in the early 20th century exploration of Antarctica, his life is not well-recorded in contemporary documents. Fortunately, Lashly wrote a simple diary of his experiences on the Discovery expedition (Ellis, Reference Ellis1969) and, on the Terra Nova expedition, he kept a record of the return journey of the last support party, during which he and Tom Crean contrived to disobey the dying Lieutenant Evans’ order to abandon him and save themselves and, instead, hauled him to safety. This event was told in Lashly's unedited words in Cherry-Gerrard's The worst journey in the world (Cherry-Garrard, Reference Cherry-Garrard1937). Lashly received the Albert Medal from the King for his bravery and Teddy Evans’ mother expressed her particular gratitude to Lashly by giving him a framed photograph of herself inscribed ‘. . . in grateful remembrance of a mother for the saving of the life of Commander E R G R Evans, RN’ (Dundee Heritage Trust, K.30).

A small number of Lashly's private letters have also survived, including several written to fellow explorer Reginald Skelton (Lashly Reference Lashly1910), and poet and teacher Robert Gibbings (Lashly Reference Lashly1938). This paper draws on these unpublished letters and also artefacts held by the Dundee Heritage Trust.

Fig. 1. Photograph of Teddy Evans’ mother given by her to Lashly.

Lashly was born into a tenant farmer family in the Hampshire village of Hambledon. He grew up loving the countryside, learning the skills of land husbandry and thatching from his father and the more mechanical techniques of late 19th century farming as a ‘carter’ on the estate. Country life was in his soul. Captain Scott (Reference Scott1905) records how, on 15 December 1903, he was leading a three-man sledging team of himself, Lashly and Seaman Evans across Antarctica's Victoria Land when the sledge began to slide out of control and Scott and Evans disappeared down a crevasse. Lashly's quick thinking and strength saved the sledge and himself from following them and, as he held on to the sledge with one hand, he withdrew their skis with his other and used them to bridge the crevasse and secure the sledge. While Lashly held them secure, Scott was eventually able to clamber up to the sledge and between them he and Lashly hauled up Evans. Scott believed that Lashly had undoubtedly saved their lives (Ellis, Reference Ellis1969, p.91). His diary then tells how after the near disaster the group moved cautiously down a valley towards a moraine of mud. On arrival, Lashly could not help but observe, ‘What a splendid place for growing spuds!’ In 1958, geologist and Antarctic explorer Collin Bull studied the very valley Scott, Seaman Evans and Lashly had explored, the first person to visit it since Scott's expedition. He collected some of the soil and sowed grass seed in it. The grass grew perfectly well, suggesting that Lashly's instinct about potatoes was probably right! (Hutchinson, Reference Hutchinson2003).

Lashly's older brother took up the mantle of their father's trade as a thatcher. His other two brothers left Hambledon to join the Army. Torn, perhaps, between the security of home and the draw of travel Lashly chose the more adventurous option and within days of his 21st birthday set off for nearby Portsmouth to sign up for the Royal Navy. He left behind in Hambledon a clue to his decision. At Christmas 1888 he had presented his friend and future wife, Alice Cox, with a copy of the Book of Common Prayer (Dundee Heritage Trust, ROY.13) inscribed in his simple handwriting with a quote from Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's (Reference Longfellow1839) Hyperion of a motto discovered in a German graveyard:

‘Look not mournfully into the past. It comes not back again. Wisely improve the present. It is thine. Go forth to meet the shadowy future, without fear, and with a manly heart.’

It would have provided a suitable gravestone memorial for Lashly himself, but for his request that his grave in the Hambledon churchyard should be unmarked.

Fig. 2. Book of Common Prayer given by Lashly to Alice Cox.

Lashly took with him to the Royal Navy training ship HMS Asia at Portsmouth the basic skills of reading and writing learnt in the village elementary school, a love of singing acquired from his membership of the village church choir and a private but sustaining faith in God. He was sufficiently fit and strong to be accepted immediately into training for the relatively new rating of ‘stoker’. The title is a little misleading. In a recruiting feature of the time, The Graphic (1890) argued that ‘in these days of machinery the stoker is an almost more important personage on board a war-ship than Jack Tar himself’. Lashly's stoker training was remarkably wide-ranging from the use of firearms and the cutlass to advanced mechanics. At 5 ft 6.5 in (169 cm) he was not a particularly tall man but, according to Scott, ‘of magnificent physique’ (Ellis, Reference Ellis1969, p. 91). A teetotal non-smoker all his life, he took every opportunity to maintain his fitness, even to the extent of playing hockey and soccer on the ice sheets of Antarctica during Scott's expeditions. His letters home often spoke of his love of physical challenges. To his brother Charles he wrote,

‘The best of it is the sledge trips. I don't mean to say it is all honey dragging 200 pounds behind every day for a month or 6 weeks but you are never healthier in your life’ (Lashly Reference Lashly1903).

Lashly's early years learning the stoker's trade were largely uneventful. His first posting was for three years on HMS Terror, a floating barracks in the Royal Naval Dockyard in Bermuda. But soon after his return to Portsmouth he joined the first cohort of men to serve on the state-of-the-art HMS Royal Arthur, a newly constructed steel cruiser launched famously by Queen Victoria in 1891, and made rapid progress to Stoker First Class.

His naval record (The National Archives of the UK, ADM/188/211) describes his character as ‘very good’ at every level of his training and on every ship he served in, something which no doubt brought him to mind when in 1901 Captain Scott asked his fellow officers to recommend men to join the National Antarctic Expedition. Scott's ship, Discovery, was purpose-built, combining the strength of traditional whalers with the power and control of the new steam engines. He chose most of his team for their skills in seamanship and their Royal Navy discipline. The combination of a stoker's strength and contemporary technical skills was an ideal qualification for the expedition and certainly in the case of Lashly proved to be essential, not only on the ship but also in coping with the practical issues of camp construction and the maintenance of skis and other equipment. On the second expedition he proved particularly valuable to Scott as a mechanic for the unreliable motorised sledges, which he had been trained to drive and which featured in his letters to his colleague from the Discovery expedition, Lieutenant Reginald Skelton.

Lashly and Reginald Skelton

Engineer-Lieutenant Reginald Skelton was First Engineer on the Discovery expedition and supervised the construction of the ship in Dundee. He appears to have got on well with Lashly who he described as ‘by far and away the finest man in the ship’ (Crane, Reference Crane2007) and was pleased with a German silver model of a sledge which Lashly made for him (Skelton, Reference Skelton2004). They shared an enthusiasm for Antarctic sport and the same frustration with some of the more eccentric projects imposed on them, not least a windmill generator which had been poorly designed.

In 1909, Captain Scott recruited Skelton for his second expedition and even took him to France to see the trials of motorised sledges, an idea which Skelton had proposed seven years earlier while on the first expedition and which Scott now made an important element of his attempt on the Pole. Skelton anticipated an invitation to become second-in-command but at the last minute Scott did a deal with Lieutenant E.R.G.R. Evans to make him his deputy instead, eventually persuading Skelton to withdraw from the expedition altogether. Although disappointed he got on with developing an outstanding career, initially with the Royal Navy Submarine Service. But he kept in touch with the expedition's progress through correspondence with Lashly who supplied him with detailed information about the largely disappointing performance of the motor sledges.

Fig. 3. Lashly photograph from the Terra Nova expedition.

Fig. 4. Reginald Skelton.

The motor sledges

Lashly received a letter from Skelton in 1910 while waiting at Lyttelton, New Zealand, for the Terra Nova to set out on its final leg to the Antarctic. He replied with news of the preparations for the next leg of the journey. After explaining how busy they had been repairing the ship's engine (‘we have had to have the crank shaft out and bedded and what a scrap lot the brasses were’) and the difficult task of re-loading the ship for its journey to the south (‘we did not get any help from the war ships so we have had it pretty stiff’) he reassured him that two of the three ‘motors’ were safely on-board. Nothing had yet been announced about the role of the motor sledges but he wrote that he anticipated that he, Bernard Day (engineer in charge of motor transport) and biologist Edward Nelson would be leaving on the first motor sledge journey soon after they arrived in the Antarctic.

On 21 October 1911 Lashly (Reference Lashly1910) wrote from ‘winter quarters’ to Skelton to inform him that there were problems with the unreliable sledges. Scott, whose biographer Turley (Reference Turley1914) argued had ‘an intense, almost pathetic, desire that the sledges should be successful’, wrote optimistically in his diary on 24 October that ‘the inevitable little defects cropped up. Day and Lashly spent the afternoon making good these defects in a satisfactory manner’ (Scott, Reference Scott1913, p. 437). In his frank letter to Skelton, Lashly was perhaps more realistic:

‘We have had to make good a lot of defects. . . The water tank at the back of the engine with the exhaust running through, caused the after cylinder to overheat so we have done away with it and fitted some straight pipes to try to overcome the heating.’

They also fitted a bonnet over the engines to create a cooling effect from the draught.

There were other design problems. ‘The aliminun (sic) on the bottom of the runners completely done for the rollers, but we have repaired them and made new ones,’ wrote Lashly. The back axle-casing of Day's sledge broke in half and had to be repaired but Lashly was optimistic that it ‘seems as strong as before. I hope it will get to the Beardmore. If we get there at all with them we shall leave them there as we are only taking petrol for that distance’.

Lashly told him of Scott's proposal to send out the motor sledges first to lay depots for the attempt on the Pole, followed by a group with ponies and another with dogs – ‘and if the motor sledges don't go and the ponies overtakes us Mr Evans and myself leaves the motors and goes with the main party’. In the event they just managed to reach the proposed meeting point before the machines gave out.

Another letter from Skelton was among the post delivered by the Terra Nova when the ship arrived in 1912 to re-supply the expedition. By then, Scott and his four companions were away on their attempt at reaching the South Pole. Lashly, Teddy Evans and Tom Crean, having survived their remarkable return journey as the last support party, arrived at base just in time for Lashly to write a reply before the Terra Nova set off for New Zealand. ‘The motors did not go far as they were not powerful enough to pull the load required of them,’ Lashly explained. They would only manage about a mile before over-heating then, when they had cooled down, the carburettor had to be made warm so they could start the engine again. ‘Mr Day's car only went about 30 miles altogether and mine about 50 from Cape Evans’. He also reported that the ‘big end brasses were also a weak spot as we broke three up completely’. Eventually, as Lashly had anticipated in his previous letter, they had to abandon the motors and began man hauling ‘200 pounds per man’ of supplies to be stashed in depots for use when the Polar party returned.

Fig. 5. The motor sledges team.

After the winter following Scott's journey to the Pole Terra Nova arrived to take the surviving members of the expedition home. Lashly (op cit) wrote a long letter to Skelton using several sheets of official expedition notepaper, the first of which was franked with an expedition stamp and postmarked British Antarctic Expedition, 18 January 1913, part of the last of four lots of mail to be sent from the Victoria Land official post office (of which Captain Scott had been made postmaster!). He wrote at the top, ‘I have sent these – if you would like one or two more I can let you have them’. He reported a little about the events which led up to the discovery of the bodies of the Polar party in the spring, before concluding his letter with some reflections on the motor sledges in which Captain Scott, and even Reginald Skelton, had placed high hopes.

‘I am sorry the motors did not go better, the longest run we could get out of them on the barrier was one mile then we had to stop one hour to cool down before we could move again.’

When the snow was hard and ridged the sledges performed better and Lashly reports that on one occasion he was able to do four miles without a stop, but ‘soft snow was all against us’. The one success he did concede was that they proved useful in moving large quantities of supplies to Corner Camp ‘which was a great deal of help to the ponies’.

More than machines

In some respects these letters are technical reports by a stoker to an Engineer-Lieutenant on practical aspects of a shared project. Lashly always retained an element of formality when he wrote to Lieutenant Skelton, beginning his letters ‘Dear Sir’ and concluding ‘yours faithfully’ or even ‘yours respectfully’. But Skelton's Discovery diaries (Skelton, Reference Skelton2004) suggest that the relationships he had built with his men on that expedition were close and Lashly's letters contain personal material and observations on wider aspects of the expedition. In his letter from Lyttelton, Lashly seems to sense Skelton's disappointment at being left out of the expedition and he begins it with some encouraging comments:

‘I hope you will keep on at the submarine depot for a long time as I am sure you have the submarine service well in hand. I know everybody wants you to stay,’ adding, diplomatically, ‘Capt Scott, Dr Wilson and all the rest wished to be remembered to you sir.’

Lashly always showed interest in Skelton's career. His reply to Skelton's letter delivered by the support ship in 1912 began with Lashly congratulating him on the year's extension he had received to his job at Fort Blockhouse (the pioneering Naval Submarine School at Gosport). When Lashly eventually arrived back in Cardiff a letter from Skelton welcoming him back awaited him. Skelton had already moved out of the submarine service to take up a position on HMS Superb and Lashly in his reply wished him well in his new position, ‘I hope you have got a good staff under you’.

In addition to such personal matters Lashly frequently wrote, sometimes at length, about other aspects of the expedition. In his 1910 letter from Lyttelton he reported how Scott had sacked Lieutenant Riley, the ship's Chief Engineer, no doubt aware that Skelton would have been particularly interested to hear that the ship sailed from New Zealand without a commissioned officer in charge in the engine room! He also commented perceptively on the sacking of Thomas Feather, who had served as Boatswain on the Discovery, over what was explained as a falling out with Lieutenant Renwick, adding ‘but really the truth is too much drink’.

In the letter sent back with the support ship Lashly described the polar journey up to the point at which Scott's team of five set off for the Pole in some detail and, reflecting the general optimism of expedition members at this time, added, ‘which I don't think there should be any doubt about them reaching’. He also summarised the return journey of his own support party providing Skelton with a foretaste of the dramatic adventure which would not be made public in any real detail until Apsley Cherry-Garrard's report in 1922:

‘We on our return experienced very thick weather and blizzards but we reached Mt Darwin depot with very little food. The next depot being 57 miles off and 3½ days provision to do it in. This took us 4½ days to do owing to getting into such bad ice pressure on the glacier. The next day we started for the next depot 51 miles with 3½ days food. Mr Evans being totally blind and on the barrier he began to develop scurvey and looseness of the bowels which gradually got worse and things became rather serious as he could not stand, finally we had to put him on the sledge and make make (sic) the best of our way with him but on arrival at Corner Camp he collapsed and we had to stop.’

At this point Tom Crean set off on his brave, lone journey to raise the alarm at Hut Point.

Lashly concluded this letter on a positive note reassuring Skelton that Lieutenant Evans was well on the way to recovery with rest and fresh food. The arrival of Scott's group was anticipated at any moment and he wrote in a very matter-of-fact way that, ‘the dogs are gone out to meet the last party’, little knowing that Seaman Evans was already dead and within two days Captain Scott (op cit) would be writing in his diary entry for 2 March, ‘we have suffered three distinct blows which have placed us in a bad position’.

Similarly, in his final letter from the Antarctic in 1913, despite beginning by saying he was unable to tell Skelton more than he might have already read in the papers concerning Captain Scott, Lashly nevertheless described the initial attempts to meet up with Scott's party returning from the Pole and the eventual discovery of the bodies seven months later. He explained how dog teams were sent out initially to see if Scott was at One Ton Depot and later how Dr Atkinson with a seaman had taken a week's provisions to Corner Camp depot, but he avoided writing much about the question which was beginning to be discussed widely, especially in the newspapers, whether more could have been done to save the Polar party. Interestingly, in light of more recent discussions about the causes of Scott's demise, he went on to observe:

‘One thing is almost certain, is, that had they reached One Ton Depot they would not have reached Hut Point as the weather was so bad, and although the food and fuel there was ample, it is doubtful whether they were in a fit state to carry enough to take them 120 miles.’

World War I

Lashly was first and foremost a Royal Navy man. He signed up initially for 12 years but had no hesitation about signing for a further ten years in 1901. Terra Nova arrived safely back at Cardiff in June 1913. Lashly was now 45-years-old and had completed his period of service with the Navy so was entitled to retire with a pension, once he had finished a temporary appointment as ship keeper while the ship was renovated in Cardiff Docks. In his ‘welcome home’ letter, Skelton had offered to find him a job. From 30 Sapphire Street, a small terraced boarding house a short walk from the docks, Lashly wrote to Reginald Skelton on 6 June 1913 declining the offer.

‘I shall not apply just yet as I must try to get my leave first. Commander Evans is going to the Admiralty to get what he can for the service men, but I cannot get any further advancement so I might as well leave, and don't feel like going on any further for 5th five.’

He took up a shipping related post as a tape holder with the Board of Trade in Cardiff Docks but also signed up for the Royal Fleet Reserve at Portsmouth in October 1913 – which meant that his adventures and his contribution to naval history had not quite finished. Britain was soon at war and on 2 August 1914 Lashly was back in training on HMS Victory II, the depot ship for the Royal Naval Division. He joined the battleship HMS Irresistible on 1 September 1914 and the following month was at Dover under the command of Admiral Hood. The ship's duties included the bombardment of German army forces along the Belgian coast in support of Allied troops fighting on the front. After other duties nearer to home, Irresistible eventually set sail for the Dardanelles where she was mined while taking part in the bombardment of Turkish forts. The engine room flooded and only three men escaped from it. The water pressure broke down the midship bulkhead, and the port engine room also flooded. Then they came under heavy Turkish fire and the captain ordered the crew to abandon ship. HMS Wear, despite enemy fire, managed to rescue 28 officers and 582 men from Irresistible.

The Captain of the light cruiser HMS Amethyst reported that on the next day,

‘vacancies in our complement filled up by a draft from the crew of Irresistible. They arrived with no kits and very few clothes’ (The Naval Society, 1919).

Among this ‘draft’ was William Lashly. He became an official member of the Amethyst crew for the next ten months before eventually returning to Portsmouth where he remained, attached to the HMS Victory base ship, until his demobilisation on 10 February 1919.

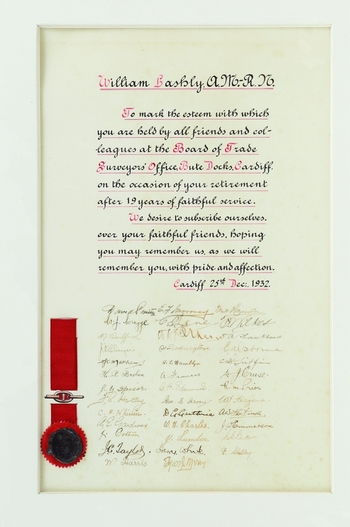

After the war, Lashly returned to his tape holder job in Cardiff where he completed 19 years of service. When he eventually retired on Christmas day 1932, 38 colleagues presented him with a handwritten and signed scroll,

‘to mark the esteem with which you are held by all friends and colleagues at the Board of Trade Surveyors’ Office Bute Docks Cardiff. . . We desire to subscribe ourselves ever your faithful friends, hoping you may remember us as we will remember you with pride and affection’ (Dundee Heritage Trust, ROY.21).

Antarctic enthusiast

In the literature (for example, Ellis Reference Ellis1969, Cherry-Garrard Reference Cherry-Garrard1940) William Lashly is generally portrayed as a reserved and self-effacing man. Yet he was also very proud of what he and his colleagues had achieved and was always happy to share their experiences. He retained an active interest in Antarctic matters in Cardiff where he lived and worked after returning from Scott's last expedition. He was involved with meetings at the Cardiff Naturalists’ Society and gave at least one talk about his experiences to the Junior Branch (Matheson, Reference Matheson1930). When Commander Frank Wild, a veteran of Scott's Discovery expedition, gave a public lecture on 18 December 1919 on The last Shackleton expedition, Lashly was present and later wrote to Cherry-Garrard:

‘I had the pleasure of hearing Wild. . . He is a good chap and did very well.’

He also attended a lecture in January 1920 on How we kept the seas by Captain Evans (Ellis, Reference Ellis1969). In a private letter written in August 1995, Michael Tarver of the Cardiff-based Captain Scott Society reported how ‘Lashly is still remembered by some old residents at Penarth giving lantern slide lectures in church halls’ (Skinner & Skinner, Reference Skinner and Skinner2012, p. 39).

Fig. 6. Retirement scroll created by Lashly's colleagues at Cardiff Docks.

He quietly maintained friendships with expedition members. In 1926, Lashly met up with Tom Crean in Portsmouth when they were principal guests at a celebration of the appointment of Teddy Evans as Captain of the battleship HMS Repulse. Lashly corresponded with Dr Atkinson, the surgeon on the Terra Nova expedition who had named a parasitic worm after him (Campbell & Overstreet, Reference Campbell and Overstreet1994). He was a close friend to Apsley Cherry-Garrard during his difficult years following the return of Terra Nova (Wheeler, Reference Wheeler2001) and visited Gestingthorpe Hall to stay with Captain Oates’ mother to talk with her about her son. He went to the annual social gathering of expedition members in London and travelled to Cambridge to visit the newly established Scott Polar Research Institute.

He also retained links with his home village of Hambledon. In August 1913, after receiving the Albert Medal from King George V, Lashly visited his old school. The school log book records:

A most interesting lecture on the Antarctic expedition was given to 60 of the older children by Chief Stoker W. Lashly, a native of the village and an old school boy – one of the survivors of the ill-fated expedition. The time occupied 2.30 to 3.15 was full of graphic descriptions of a life at high latitudes, and at the close the Medal awarded by the King at Buckingham Palace on the previous Saturday was handed round for inspection.

The whole school then enjoyed an excellent tea, after which Lashly was sent on his way with ‘three hearty cheers’. The pupils continued their celebrations with maypole dancing and games until 7 pm (Skinner & Skinner, Reference Skinner and Skinner2012).

Lashly eventually retired from his tape holder post in Cardiff to a house he had had built in Hambledon. He named it Minna Bluff after a rocky promontory in the Antarctic which was used as a key location for vital supply depots for southern exploration and, perhaps more significantly for Lashly, a critical marker to guide homeward journeys. He was well-known in and around the village for his presentations on Antarctica.

The journey of the last support party

It was at this time that the eccentric illustrator and lecturer Robert Gibbings approached him about using his notes of the last returning party for a student book project.

The story of the return journey of the last of Captain Scott's supporting parties is as remarkable as any of the accounts of adventures experienced on the Terra Nova expedition. The most vivid description may be found in Cherry-Gerrard's (Reference Cherry-Garrard1937) The worst journey in the world in which Lashly's own record is reproduced in full and unedited. Teddy Evan's account appeared in South with Scott, a book he ‘affectionately dedicated’ to Lashly and Tom Crean (Evans, Reference Evans1938, p. iv).

When the time came for the final attempt on the Pole, Captain Scott decided to take an extra man in his group. Lieutenant Evans’ support party was therefore reduced to three men – himself, Tom Crean and William Lashly. Scott was optimistic about the returning party reaching base safely, despite the fact that the sledge-hauling team was a man short and Evans was the only trained navigator. It was only at this point that Lashly began keeping detailed notes. In an entry for 3 January 1912 he wrote of how Captain Scott had explained to them that not everyone could continue to the Pole and that his selection of the men to accompany him was no reflection on the abilities or fitness of the three who were returning. Lashly wrote:

‘We wished them every success and a safe return, and asked each one if there was anything we could do for them when we got back. . .I think we all felt it very much’ (Cherry-Gerrard, Reference Cherry-Garrard1937, p. 384).

At first, Lieutenant Evans’ party made good progress, although not without some early problems with snow blindness, crevasses and blizzards. On the 17 January they had a remarkable escape from ice ridges and crevasses on the glacier. Even the usually unflappable Lashly wrote:

‘We have to-day experienced what we none of us ever wants to be our lot again’ (Cherry-Gerrard, Reference Cherry-Garrard1937, p. 390).

On the 19 January Evans began to have severe problems with his eyes and could no longer lead the group.

On the 22 January he started to have symptoms which Lashly immediately recognised as those of scurvy. Evans soon developed diarrhoea and his general physical condition began to deteriorate. Lashly reports in his diary entry for 8 February, ‘I have now to do nearly everything for him’. A few days later they had no choice but to place him on the sledge and pull him along. Progress was inevitably very slow.

‘This morning,’ writes Lashly, ‘he wished us to leave him, but this we could not think of. We will stand by him to the end one way or other.’

On the 18 January Evans was so ill he could travel no further. Lashly and Crean agreed together that Lashly would remain and nurse him as well as he could while Tom set out alone to try to cover the 30 mile journey to Hut Point and get help. If Crean failed, Lashly would starve to death as there was very little food left.

On the evening of 20 February, Lashly and Lieutenant Evans heard the sound of dogs outside their tent. Tom Crean had made it back to base and, despite appalling weather, Dr Atkinson and the dog driver Dimitri had reached them. Lashly gladly handed over his patient to a medical professional, who later commented on the superb care that had kept him alive (Atkinson, Reference Atkinson and Scott1913, p. 300). Lashly wrote in his diary:

‘It seems to me we are in a new world, a weight is off my mind and I can once more see a bright spot in the sky for us all, the gloom is now removed’ (Cherry-Gerrard, Reference Cherry-Garrard1937, p. 405).

They returned safely to Hut Point and under the expert care of Dr Atkinson, Evans began his slow recovery. He was invalided out on the Terra Nova when the ship returned to Britain after resupplying the expedition. Back in England, Evans made a full recovery and went on to follow a distinguished career in the Royal Navy. After the survivors of the expedition returned to Britain in 1913 Lashly and Crean were invited to meet the King and to be presented with the Albert Medal for their bravery and dedication in saving Lieutenant Evans’ life.

Fig. 7. Photograph of Lashly with his medals.

It is not clear how Gibbings came across Lashly's story but the text of the small book his students produced is identical to the chapter in Cherry-Gerrard's book. When Gibbings wrote to Lashly asking for his permission Lashly was happy to oblige, arguing that the youth of the day needed to hear of the struggle of the explorers. He wrote apologetically:

‘My diary is as I dotted it down after doing a very hard days dragging. I could not bring myself to write more although many little incidents cropped up each day as we trudged along hour after hour, trusting in God to give us strength to fulfil the duty we were entrusted with and to bring back to safety Lieut Evans’ (Lashly, Reference Lashly1938).

The small, 37-page book was designed and produced by young printers’ apprentices and illustrated with engravings by students of Book Production at Reading University in a limited edition of just 75 copies. Even so, Gibbings was able to persuade Evans, by then an Admiral, to provide the foreword. He wrote:

‘This little volume is a chapter from the life of one of those steel-true Englishmen whose example sets us all a-thinking. I owe my life to Lashly's devotion and admirable duty-sense. He is one of those Yeomen of England whose type gave us Drake's men and Nelson's men and Scott's and Shackleton's men, and will do so again’ (Gibbings, Reference Gibbings1939).

Lashly was very pleased with it and wrote to Gibbings asking him to pass on his thanks to all who had a hand in its production.

Fig. 8. Lashly's Terra Nova diary produced by Robert Gibbings and his students.

Lashly's correspondence with Gibbings confirms Lashly's concern that the great adventure should not be forgotten. He was well aware that his generation of explorers was dying out.

‘We are now dwindling down,’ he wrote to Gibbings in March 1939, ‘I am really the only man that did both the Scott expeditions from beginning to the end.’

He was keen that young people should hear about what he and other explorers had achieved in the Antarctic, though he also observed, ‘I wonder will anyone go there again. I don't think so!’ On this point, at least, Lashly's intuition had been quite wrong!

William Lashly died aged 72 on 12 June 1940 in the Royal Hospital Portsmouth, just four months after his wife Alice. Apsley Cherry-Garrard had kept in touch with him over the years and wrote an appreciation for the Scott Polar Research Institute's journal Polar Record, recalling how,

‘behind that kindly smile, that half-filled the engine room hatch on Terra Nova, there were bottled up great reserves of quiet energy.’ He concluded his tribute, ‘so perhaps he is now looking for a good whack of pemmican and still singing that cheery little ditty with which he used to end his day's work on earth’ (Cherry-Garrard, Reference Cherry-Garrard1940).

William Lashly was a fully professional seaman who was deceptively strong.

‘He stripped big and looked small,’ wrote Cherry-Gerrard (Reference Cherry-Garrard1940), ‘and was as tough as nails.’

His practical contributions to Antarctic exploration were not insignificant. His strength and quick-wittedness saved Scott's life on his first expedition, and his courage and determination saved Teddy Evans on the second. But as his letters to Reginald Skelton and Robert Gibbings confirm, he was also a thoughtful and perceptive man with the ability to report and reflect beyond what might have been expected of someone of his background and education.

Acknowledgements

The author is grateful to the Dundee Heritage Trust for the use of archive photographs and to the staff at SPRI Archives for help and advice concerning the letters of William Lashly.

Excerpts appear by permission of the University of Cambridge, Scott Polar Research Institute