The expedition

The Austro-Hungarian north pole expedition of 1872–1874 was the brainchild of the German geographer and promoter of arctic exploration, August Petermann. Immediately prior to that expedition he had been largely responsible for the first and second German north pole expeditions of 1868 and 1869–1870, both aimed at exploring the east coast of Greenland, with a view to trying to reach the pole via that route. In the first case the expedition under Captain Carl Koldewey, in the ketch Grönland was blocked by ice from reaching the Greenland coast, and thereafter had no better luck in trying to reach Gillis Land in Svalbard (Koldewey and Petermann Reference Koldewey and Petermann1871). The latter island (in fact Kvitøya) had been seen from a distance by the Dutch whaler Cornelius Giles in 1707 (Conway Reference Conway1906) but had not been explored. The second German north pole expedition on board Germania and Hansa (Captains Carl Koldewey and Paul Hegemann respectively) managed to reach the east Greenland coast, but had little success in pushing towards the pole (Koldewey Reference Koldewey1874). Germania wintered off Sabine Ø, but Hansa became beset in the ice and was ultimately crushed, although her crew managed to reach the Danish settlements in west Greenland.

Following these failures, Petermann argued that a more promising line of attack, in terms of trying to reach the pole, would be via the area between Svalbard and Novaya Zemlya where, he assumed, the northward flowing waters of the Gulf Stream (or more correctly its continuation, the North Atlantic Drift) would ensure an ice-free embayment extending much farther north than elsewhere (Payer Reference Payer1876 1: 82–83).

Petermann proposed mounting a trial expedition, a reconnaissance in effect, in the summer of 1871, and recruited two individuals to lead it. One of these was Lieutenant Carl Weyprecht (Fig. 1) of the Austro-Hungarian navy (Petermann Reference Petermann, Berger, Besser and Krause1871). Carl Weyprecht was born on 8 September 1838 in Darmstadt, Hesse, in Germany. He wished to pursue a naval career but since Hesse had no navy, in 1856, he enrolled as a sea-cadet in the Austrian naval academy in Trieste (Koerbel Reference Koerbel and Nuttall2005a). During the Austro-Prussian War he served with distinction on board the battleship Drache in the pivotal Battle of Lissa against the Italians, who were allied with the Prussians, in the Adriatic on 20 July 1866, and was awarded the order of the Iron Cross III.

Fig. 1. Carl Weyprecht (Photo: Vienna: Bildarchiv der Österr. Nationalbibliothek).

While in the Caribbean on board the corvette Kaiserin Elisabeth, in connection with plans to rescue Emperor Maximilian of Mexico, Weyprecht contracted malaria at Veracruz. For a time his life was in danger but he made at least a partial recovery in hospital in Havana, Cuba (Berger and others Reference Berger, Besser and Krause2008: 12). But by 2 April 1868 he was back in Vienna.

Prior to Weyprecht's illness Petermann had offered him the position of scientific officer and second-in-command of the first German polar expedition aboard Grönland, planned for the summer of 1868. Carl Koldewey was appointed to the command of the expedition (Koldewey and Petermann Reference Koldewey and Petermann1871) but to Weyprecht's great disappointment, Koldewey countermanded Petermann's offer to Weyprecht to handle the scientific programme, in part on the grounds that he had still not fully recovered his health. Later, Weyprecht was again engaged in discussions with Petermann about becoming involved in the second German polar expedition, on board Germania and Hansa but, unfortunately for Weyprecht, Petermann arguedwith Koldewey (who was also to command this expedition) and with the Bremen Polar Society which was organising the expedition. Hence Weyprecht was again passed over. By the time Petermann again approached him with an invitation to lead his reconnaissance expedition of 1871. Weyprecht's health had improved, and he gladly accepted the invitation.

The other expedition leader was Lieutenant Julius Payer (Fig. 2) of the Austrian army. Born on 2 September 1841 in Schönau near Teplitz (now Teplice in the northwestern part of the Czech Republic), he attended the Theresian Military Academy in Wiener-Neustadt (near Vienna) from 1857 until 1859 (Koerbel Reference Koerbel and Nuttall2005b). He was decorated for his bravery in the Battle of Solferino in 1858 and in the Battle of Custozza in 1866. Between 1864 and 1868 he was also engaged in exploring and mapping the Ortler Alps in what is now northern Italy, making 30 first ascents. On the basis of this experience he was invited by Petermann to take part in the second German north pole expedition, as topographer, on board Germania, and took part in that expedition's main sledge trip north from the winter quarters on Sabine Ø as far as Kap Bismarck on Germania Land (Koldewey Reference Koldewey1874).

Fig. 2. Julius Payer (Photo: Vienna: Bildarchiv der Österr. Nationalbibliothek).

For the reconnaissance expedition of 1871 Petermann made available 2000 taler from funds left over from the second German north pole expedition and Emperor Franz-Josef added a further 500 taler. The bulk of the remaining funding was contributed by government departments and corporations (Berger and others Reference Berger, Besser and Krause2008: 25). Plans were well under way for the reconnaissance expedition when Payer happened to be dining with Count Hans Nepomuk Wilczek, who became extremely enthusiastic about the impending expedition, and offered to sponsor the main expedition the following year, and to provide funding to the tune of 30,000 gulden (Berger and others Reference Berger, Besser and Krause2008: 317), later increased to 52,000 gulden (Slupetzky 1995).

Weyprecht travelled north to Tromsø in May 1871 and chartered a small, new, ice-strengthened schooner, Isbjørn (Weyprecht Reference Weyprecht, Berger, Besser and Krause1871a). He also hired a captain, Captain Johan Kjeldsen and a crew of eight: a harpooner, four sailors, a carpenter, a cook and a ship's boy, all Norwegian (Payer Reference Payer1876 1: 84).

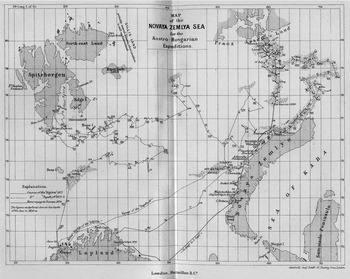

Isbjørn put to sea from Tromsø on 20 June (Fig. 3), and encountered the first ice on 28 June, to the south of Bjørnøya. Two days later the ship became beset for ten days. After working her way east along the ice edge, on 22 July she headed back west to just slightly beyond Sørkapp, on Spitsbergen. Then, unable to make any significant progress northwards in Storfjorden Isbjørn headed back east, repeatedly probing the ice edge, to just beyond Hopen. She made her highest latitude (78° 38′N) on 31 August; Novaya Zemlya was sighted later but foul weather prevented any landings. By 4 October the expedition was back at Tromsø. It had not even come close to reaching Gillis Land [Kvitøya].

Fig. 3. Map of the routes of the Austro-Hungarian expeditions of 1871 (in Isbjørn) and 1872–1874 (in Tegetthoff) and of the retreat by sledge and boat (Payer Reference Payer1876 I: following xxxi).

One of the main conclusions that Weyprecht reached from this experience was that their inability to attain a higher latitude was due to the lack of commitment on the part of the Norwegian crew. As he complained to Petermann:

Our voyage has been a very difficult one for me. You wouldn't believe what tact was required to overcome the difficulties that a Norwegian captain and a lazy crew can place in one's way. Never support such an expedition again, dear Doctor. Nine times out of ten you would be throwing your money into the water to no purpose (Weyprecht Reference Weyprecht, Berger, Besser and Krause1871b: 334–335).

This experience with the Norwegian crew of the Isbjørn led directly to the crew of the expedition vessel for the main expedition in 1872–1874 being entirely Austro-Hungarian.

This was not the only major decision that emerged from the 1871 voyage. It was decided that a steamer was essential for the main expedition and since, through Wilczek's generosity, and Payer's and Weyprecht's diligent fund-raising activities, funding was not a major problem, it was decided to build a specially designed vessel. That vessel, named Admiral Tegetthoff (after the victor of the Battle of Lissa) was ordered from the Tecklenborg yard in Bremerhaven (Berger and others Reference Berger, Besser and Krause2008: 13). Weyprecht spent most of the winter of 1871–1872 in Bremerhaven, supervising the building of the ship. She was launched on 13 April, a bark-rigged steamer of 220 tonnes, with a steam engine of 100 hp. The engines had been built at Stabilimento tecnico Triestino in Trieste (Krisch Reference Krisch1875). She ran her trials on 8 June (Payer Reference Payer1876 I: 122).

Tegetthoff put to sea from Bremerhaven on 13 June 1872 (Payer Reference Payer1876 I: 121). Her complement totaled 24: Schiffsleutnant Carl Weyprecht, Oberleutnant Julius Payer, Schiffsleutnant Gustav Brosch, Schiffsfähnrich Edward Orel, medical officer Dr. Julius Klepes (a Hungarian), engineer Otto Krisch (who had supervised installation of the ship's engines), bosun Pietro Lusina (an Austrian merchant captain who had signed on as bosun, in order to take part in the expedition), a carpenter, a stoker, 11 seamen (all from Fiume (now Rijeka) and area, and two hunters from St. Leonhard in Passeier in the Tyrol (now San Leonardo in Passiria in northern Italy), Johan Haller and Alexander Klotz. Payer had employed Haller during his surveys in the Ortler Alps between June and October 1868. When Payer wrote to Haller to invite him to join the expedition, in February 1872, he asked him to find another suitable jäger. Haller then recruited Klotz (Haller Reference Haller1959). Captain Elling Carlsen would join the ship, as ice-master and harpooner, in Tromsø. The latter had many arctic voyages to his credit, mainly for hunting walrus, and in the previous year he had discovered Barents's wintering site at Ledyanaya Gavan’ (Icy Harbour) in northeastern Novaya Zemlya (Holland Reference Holland1994: 285). Also on board were eight dogs, six from Vienna and two from Lapland. All orders on board were given in Italian (the language of the crew, who spoke a Venetian dialect), but other languages in regular use were English, German, Slovenian and Hungarian.

The ship reached Tromsø on 3 July, but replenishing bunkers and repairing a leak delayed her departure until 13 July, when she headed north into the Barents Sea (Payer Reference Payer1876 I: 125) (Fig. 3). The objective was to round Novaya Zemlya on the north and, if possible, to attempt the northeast passage to Bering Strait. If ice conditions were particularly favourable, an attempt at the north pole was not excluded. The first ice was encountered on 25 July, at 74° 0′ 15″ N, that is less than 170 nautical miles (315 km) north of Nordkapp. This was not a good omen. The ice became steadily closer as Tegetthoff worked her way north, although she was temporarily beset for a few days (29 July until 2 August). By 7 August she was off Poluostrov Admiral'teystva [Admiralty Peninsula], and on 12 August off the Ostrova Pankrateva [Pankratev Islands] encountered a schooner which was flying the Austro-Hungarian flag; this was Isbjørn, again under the command of Captain Kjeldsen. She had been chartered by Count Wilczek (who was on board), and was on her way to establish a depot on the north coast of Novaya Zemlya, to which Tegetthoff's crew would be able to fall back in case of emergency. The two vessels continued north in company, and next day (13 July) Tegetthoff's crew assisted that of Isbjørn in sledging the fuel and provisions ashore across the fast ice and establishing a depot on one of the Ostrova Barentsa (Barents Islands). The site was easily distinguished by three conspicuous rock outcrops known as the ‘Drei Sarge’ [Three Coffins]. On 20 August the two vessels separated and Tegetthoff headed north. But on the very next day (21 August), at 76° 22′N; 63° 3′E, off Russkaya Gavan’(Russian Harbour), she became solidly beset. She would not move under her own steam again.

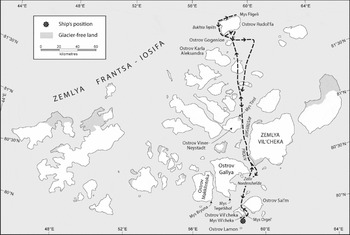

The ship drifted with the ice, initially northeastward until 2 February 1873, when the drift changed to generally westward through the spring and summer. But then on 1 August the drift changed again to generally northward. Then, around noon on 30 August 1873, land was sighted in the distance to the northwest. It was named Zemlya Frantsa-Iosifa (Franz Josef Land). The ship continued to drift, somewhat haphazardly as to direction, until the end of October, when she found herself beset in the fast ice at 79° 58′N, off the south coast of an island that was named Ostrov Vil'cheka [Wilczek Island] (Fig. 4). Several brief trips were made ashore in early November, but then the onset of the winter darkness meant that any longer exploring trips would have to be postponed until the spring of 1874.

Fig. 4. Cape Wilczek, Wilczek Island. Krisch's grave lies at the foot of the cliff. (Photo; Heinz Slupetzky).

Weyprecht, Payer and the officers and men then settled down, no doubt somewhat impatiently, for a second winter. In the spring three sledge trips were mounted to explore as much of the unknown landmass as possible. In each case the sledge parties were led by Payer, while Weyprecht remained in command of the ship. The first sledge trip was quite short, lasting only from 11 until 15 March. The party consisted of Payer and six men (including Haller and Klotz), with three dogs. They sledged past the west side of Ostrov Vil'cheka to Mys Tegetkhof [Cape Tegetthoff], the southern tip of Ostrov Gallya [Hall Island] and explored Zaliv Nordenshel'da [Nordenskiöld Fjord] and, briefly the Lednik Sonklar [Sonnklar Glacier] (Fig. 5 and 6).

Fig. 5. Modern map of Franz-Joseph Land, showing route of Payer's major sledge trip.

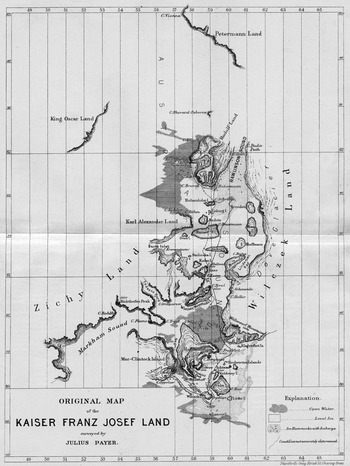

Fig. 6. Payer's map of his sledging journeys on Franz-Joseph Land (Payer Reference Payer1876 II: following xiv).

On the day after they returned to the ship the engineer, Otto Krisch, died. He had displayed the first symptoms of tuberculosis as early as February 1873 (Krisch Reference Krisch1875), and then in early February 1874 he also showed the first signs of scurvy. He had lain in a coma for two weeks prior to his death (Krisch Reference Krisch1875). He was buried in a deep crevice in the rock at Mys Vil'cheka [Cape Vilczek] on the shores of Ostrov Vil'cheka on 19 March (Payer Reference Payer1876 II: 72); a wooden cross with a brass plaque, giving his details, was erected over the grave (Krisch Reference Krisch1875) (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7. Otto Krisch's grave. (Photo: Heinz Slupetzky).

Payer's next sledge trip was remarkable not only for its length (almost a month) but also for the fact that given the relatively late date, and the general ignorance of the ice regime in this area, Payer and his men were constantly haunted by the fear that ice break-up might occur, and that the ship might drift away, before they returned. At the same time, if the ship were still there when they returned, this meant that it would probably remain beset throughout the following summer and that they would be faced with a sledge-and-boat trip south to safety, a daunting prospect. Accompanied by six men (including Haller and Klotz) Payer set off on 26 March and headed north between Ostrov Vil'cheka and Ostrov Sal'm [Salm Island], then on northward between Ostrov Gallya and Zemlya Vil'cheka [Wilczek Land] (not to be confused with the much smaller Ostrov Vil'cheka), into the southern reaches of the major north-south channel, Avstriyskiy Proliv [Austrian Strait], which provides access to the eastern part of the archipelago. Surveying as he went (and climbing to suitable vantage points on various islands for this purpose), Payer pushed steadily north. At Mys Shretter [Cape Schrötter] on Ostrov Gogenloe [Hohenlohe Island], to achieve greater speed he decided to split his party (Haller Reference Haller1959). Leaving Haller, Sussich and Klotz (who had an injured foot), he himself pushed on with Orel and Zaninovich on 9 April. As Payer and party climbed the Lednik Middendorfa [Middendorf Glacier] on Ostrov Rudol'fa [Rudolph Island], an accident occurred which allowed Haller to show his mettle as an experienced alpine climber. Payer and party had been travelling unroped, when Zaninovich, the sledge and the dogs fell down a crevasse. Payer himself barely escaped. He then raced back to Mys Shretter to fetch Haller. The latter brought a climbing rope, abseiled down into the crevasse, and rescued Zaninovich, the dogs and the sledge (Haller Reference Haller1959).

On 12 April Payer and party reached Mys Fligeli [Cape Fligely] at 81° 45′ 59″N, on Ostrov Rudol'fa (Payer 1886 II: 162). This is the northernmost tip of the archipelago, but Payer was convinced that he could see further islands to the northwest (which he named King Oscar Land) and to the north (Petermann Land), that he estimated to lie 60–70 miles (100–115 km) away. These must have been either cloud formations, or miraged hummocks, since no land exists there.

Starting back south on the very next day (13 April), Payer and his men were enormously relieved when, on rounding Mys Orgela [Cape Orgel] on Ostrov Vil'cheka on 22 April, they sighted the ship, still lying beset in the ice where they had left her.

This sledge journey represents a very creditable feat of arctic exploration. In 27 days Payer and his men had sledged a minimum of 230 nautical miles (425 km). Payer had been surveying assiduously throughout, and this inevitably had demanded some quite lengthy halts. The names he bestowed on the islands, headlands, bays, straits etc. represent a permanent memorial to his diligence: names such as Ostrov Viner Neystadt [Wiener Neustadt Island], Mys Tirol [Cape Tyrol], Ostrov Gogenloe [Hohenlohe Island], Bukhta Teplits [Teplitz Bay]and Ostrov Carla Aleksandra [Carl Alexander Island]. He made a significant error in assuming that the islands he could see to the west of his route were simply headlands of a larger landmass, which he named Zichy Land. In addition, given that the visibility was often limited while he was surveying, and since the snow cover on the land made it difficult to distinguish between land and sea ice, the shapes of the islands, and the relative distances between them are in many cases somewhat inaccurate. Nonetheless this was a very commendable effort.

A week after this important sledge trip, Payer set off again on a third, short sledge trip, on 29 April. Accompanied by Brosch and Haller he sledged to Mys Bryuna [Cape Brün] on Ostrov Makklintoka [McClintock Island]. Ascending the Lednik Simony [Simony Glacier] they reached the summit of Mys Bryuna, from where Payer took a round of angles. They were back on board the ship by 3 May (Payer Reference Payer1876 II: 208).

By this point it had been decided that there was no alternative but to abandon the ship and to head south. For the following ten days, the entire focus was on preparations for what clearly would be a very challenging trip. Initially three boats were taken, these being mounted on solidly-constructed, low sleds. Each was hauled by a group of seven men, commanded by Weyprecht, Payer and Brosch. In addition provisions, equipment, clothing etc. were hauled in three separate sledges. The weight on each sledge was approximately 1800 lbs (820 kg), and the amount of provisions and equipment was calculated to last 3–4 months (Carlsen Reference Carlsen1875: 62).

Thus the boat-sledges would be hauled forward for a convenient distance, then the crew would walk back to bring forward their second sledge. Rather than tents that were pitched on the ice every night, tents were rigged on the boats, and the men slept fully clothed, in these somewhat cramped quarters. Later it was decided to relieve the cramped quarters in the boats, by sending a party back to the ship to recover a fourth boat. The group thereafter was divided into four parties, Carlsen being in charge of the fourth one. A small dog sledge was also used, for making short, relatively fast excursions.

Weyprecht's journal of the retreat, 15 May until 3 September 1874

The journal is preserved in the Österreichisches Staatsarchiv in Vienna (Weyprecht Reference Weyprecht1874a) and is reproduced along with much relevant information is available in the book by Berger and others (Reference Berger, Besser and Krause2008).

Plan for the boat voyage. Our route will be straight south, as far as possible. In any deviations from this course in general it will be better to hold to the west rather than to the east, since in the former direction we can expect more broken ice. Our first goal is Wilhelm Island (75° 53′E).Footnote 1 If the boats reach it before the middle of August, and they still have 10 days’ provisions in hand, the provisions depot at the Three CoffinsFootnote 2 will be left untouched and the voyage will be continued along the coast to Matochkin Shar without stopping. If we reach the coast of Novaya Zemlya only after the Norwegian and Russian ships have left it, after renewing our provisions at the Three Coffins, we'll have to follow the coast to Goose Land [Gusinaya Zemlya] (72°) and from there begin the crossing via Kolguev Island [Ostrov Kolguev] to the White Sea. In case of extreme necessity we'll be able to winter on this island which is inhabited by Samoyeds. These plans are also binding, in the event that the boats become separated.

The most careful attention is to be paid to avoiding the latter situation. The normal situation will be that even under favourable circumstances the boats should never be out of hearing range of the signal horn from each other, and the leading boats will always be responsible for adhering to this instruction.

If, despite this the boats become separated, on touching first at the southern tip of Wilhelm Island then at the northern tip of Admiralty Peninsula [Poluostrov Admiral'teystva], messages are to be deposited under a cairn, then each boat is to continue its voyage independently according to these arrangements.

Each morning, provisions will be distributed by Lieutenant Orel, Dr. Kepes and Bosun Lusina for each party for breakfast and supper. Lt. Brosch will make the calculations about provisions. One man from each boat's crew will function daily as cook.

It must be strictly ensured that no disorderliness is allowed to develop in the boats. Every day before starting the men are to wash and to stow their bundles, rolled up with their night things, under the seats.Footnote 3 Only those who have been given permission by the respective boat's commanders will be allowed to shoot. All the shot is to be reserved for the open-sea voyage. All other details will depend on circumstances.Footnote 4

15.5. Fair weather. Observations discontinued; journals wound up and packed.Footnote 5 I'm still continuing my attempts with the oil lamps, but the heat at the wicks is too great; they become charred too far down and then no longer draw up any oil. Orel has not been in the best of health for a few days. Brosch set up a new stake in order to get a longer baseline facing the western mountains. The snow is already very soft; one sinks to halfway up one's calves. It will be heavy going for us with the enormous weights, but we can't set off before 20 May, since otherwise the provisions will run out before the period that is most favourable for the trip with the boats. Today Carlsen was inebriated. From what? From the alcohol in which his zoological collections ought to have been packed.

16.5. Thermometer to +2°. The snow soft. The boats are now fully equipped.

17.5. Mild weather. Sunday rest. Was on shore and deposited under the cairn on Cape Wilczek [Mys Vil'cheka]Footnote 6 a document with the details of our departure and a minimum thermometer. The thermometer is stuck in a wooden case which is tied to the stake standing in the cairn, and covered with about 6 inches of rocks in such a way as to allow air circulation.Footnote 7 The snow is already very soft so that walking is very tiring. Stiglich's injury is completely closed today.

18.5. ENE wind with light drifting snow. Had all 8 sledges and boat-sleds thoroughly polished; the large hatch caulked.

19.5. A stiff ENErly with heavy drifting snow. The boat-sled runners given their last check and polished with soap. Instructions issued for officers and men.Footnote 8

20.5. A bright morning. Finishing touches added to the boats. A short trial trip revealed that both the sledges and the boats can easily be hauled by 7 men. Left the ship at 8.30 in the evening. The flags hoisted on the boats; the ship's flag nailed to the topmast. Only a few paces from the ship the going was already so bad that we had to harness 10 men to each boat, and even then we could advance only with the greatest difficulty. With every step one sank to over one's knees.Footnote 9 The snow is like pure sand; the boat-sleds slide somewhat better, but the sledges dig into the granular snow so badly that in places they have to be partly unloaded. The dogs are of no help at all when harnessed to the sledges; on the other hand, harnessed to their own small sledge they can haul 200 lbs.Footnote 10 To move everything ahead three trips have to be made. Under these circumstances by 3 o'clock (on 21.5) we had covered only ![]() mile,Footnote 11 with a break of 1

mile,Footnote 11 with a break of 1![]() hours. The men have no appetite; they are too thirsty. So nothing but unexpectedly slow progress and problems.

hours. The men have no appetite; they are too thirsty. So nothing but unexpectedly slow progress and problems.

21.5 p.m. Slept or rested with varying degrees of success until 4 p.m. The temperature was very pleasant. Furs and a blanket were quite sufficient.

22.5 a.m. North wind, −5°R.Footnote 12 Broke camp at 6 p.m.; worked till 11 then rested till 1, then hauled again until 5.00. No porter in the world works for 8 hours so strenuously as we. In places the going is atrocious; the sledges often have to be half unloaded. For almost half the time the men have to haul at the word of command, in order to advance in jerks. We are now somewhat beyond the southern end of the baseline; p.m. −5°R. Wakened at 5 p.m. Had slept well, not very hungry but tormented by thirst, mainly while and after working. Melting snow in one's hand and licking up the drops. Payer went back aboard with ZaninovichFootnote 13 and the dogs. Brought back tea to refresh us. Boots frozen and always full of ice. Set off at 7; hauled till 11, then 2 hours’ rest. 1 tin can full of water per man, mixed with the tea that Payer had brought, and a bottle of rum for everyone – a real treat.

23.5. Set off at 1.00; hauled till 4. The boats are moving relatively easily, but the sledges terribly badly. During last night's camp bear No. 62 was shot. Bear soup. (Payer returned from the ship with treats.) The uppers of our boots somewhat too short for this snow, since it gets in from the top. After a short time the leather is frozen hard. Boots and stockings full of ice. Something that is really unpleasant is the total lack of mental activity during the rest breaks. One simply lies huddled together and sleeps or thinks and ponders. Under these circumstances one keeps one's journal much more thoroughly than normal. One becomes obsessed with writing. One's bones have become accustomed to sleeping on the hard surface. After I got up today I felt as well as if I had slept in a bed. We are now somewhat less than 2 miles from the ship. Off at 4 p.m. The dogs are now pulling just the dog sledge, and along with one man are steadily moving 700 lbs. They can haul only a maximum of 200 lbs at one time. The man with them really has to work hard. He constantly has to load and unload, push, shove, swing his stick, and in places even has to pull sledge and dogs. If the sledge sticks on a piece of ice, the brutes calmly lie down, and no power in this world will make them move any further until the obstacle has been overcome by the man driving the sledge. Payer has taken over this dog-driving function.Footnote 14

24 May. Pentecost [Whit], that happy holiday. We started it very cheerlessly. Until 11 p.m. we were making pretty good going, but then we landed among some hummocks, and had to make progress with standing pulls, foot by foot. There is now a long stretch of this miserable going ahead of us. Then we'll reach a fairly open plain, that appears to extend to the group of icebergs, to which we are now heading. Before anything else we have to reach them, in order to get an overview of our route beyond. I expect to make great advances beyond them. The going through the hummocks is abominable. All the intervening areas between the low summits are drifted-in, and frequently the sledges get bogged down and one sinks waist-deep, so that one can't get a solid foothold for pulling. The hummocks here are not nearly as high as they were in our vicinity last spring. The grounded icebergs ahead of us appear to have broken the thrust of the drifting ice during the winter.

There is much more snow lying here, but the pressure ridges don't attain nearly the same massiveness. The change of air is having a good effect on Stiglich and VecerinaFootnote 15 but Kepes can barely tolerate the strain; after a short time his pulling efforts were zero. Yesterday and today he was vomiting from overexertion. On the 21st Lukinovich was fined 50 florins because he was found stealing from the water intended for his boat's crew. The fairness with which I share things out is evident from the fact that today, while sharing out a bottle of rum that Payer had brought, I used the top of a water bottle, that contained about a thimble-full. The contents of the bottle definitely could not have been divided into 23 in any other way. The wisdom of Solomon is often required in order to be absolutely fair to everyone. Water is valued most of all. Anyone who has not suffered from thirst cannot know what a terrible torment it is to be deprived of water while carrying out strenuous work. Lusina is now using his metal spectacles case, in order to produce a few miserable drops of water, by melting snow against his chest. In order to get a good mouthful of water, one has to hold a can full of snow in one's hands for an hour, and to assist the melting process by occasionally blowing on the snow. If I filled my water bottle with snow and stuck it in my sleeping bag at night, it would produce about 2 mouthfuls of water in the morning. And the temperature was only −6 to −7°R.

25 May. Since we left the ship we've had a persistent unpleasant, damp, cold northerly wind with light snow. I had really wanted to stop for a full day of rest on Pentecost [Whit], but sitting in the tents in the boats was so boring that we got under way at midnight and travelled until 4 [a.m.]. We have left the treacherous area of the hummocks and appear to have relatively good going ahead of us. From our today's campsite we could see a flat island to the SW, of whose presence we had previously been unaware.Footnote 16 To the left of it lies a row of icebergs, towards which we are heading. This island appears to be the cause of our having enjoyed such a peaceful winter. The planks on the boat-sleds are becoming somewhat loose; today the two whaleboats had to be taken off in order to rectify the problem. We celebrated Pentecost with warm tea with milk; in my whole life I've never tasted anything as good as that tea. Payer is back on board ship again. Today he will bring us the last luxury items. We are sitting here, blowing on our soup to cool it; here one can see everyone sitting in the boats holding tin cans in both hands, blowing into them, either to melt snow to obtain water, or to melt the icebergs that are floating around in the water.Footnote 17

26 May. A NE wind with snowsqualls. Payer returned at midnight from his last excursion to the ship and brought another small barrel of very strong tea and some rum and alcohol. We set off at 6 p.m. and encountered relatively good going, and, with a 2-hour rest, covered about one mile. The icebergs ahead turned out to be large hummocks. In the forenoon we were surprised by a bear as we were walking back for the sledges without any weapons having taken the boats ahead. It paid a visit to the sledges, but retreated as we approached. In the evening Payer shot bear No. 63, but it was with his last shell, and he wasn't able to kill it, and was too far away from us. Any benefit from using the dogs is basically an illusion. In a day they transport about 600 lbs–seven 85 lb. bags – but require a powerful; man to drive them. If one deducts 100 lbs of dog food from these 600 lbs, this leaves 500 lbs. But the man driving the dogs also has to haul at least 400 lbs. Their main benefit lies in the fact that they lighten the three sledges to the extent that they can negotiate even difficult spots. We are now melting snow for water three times per day: morning, evening, and at our rest-stop; each man then receives about 4 wine-glasses full. This is sufficient, as can be seen from the fact that the men have totally stopped eating snow. Naturally not all of the cooks can be equally economical with the alcohol; on this depends the quantity of water that each boat receives. A pattern of daily activities is now in place. The cooks are called at 4 p.m. and receive their alcohol rations from one of the supply officers, Orel, Kepes and Lusina. At 5 bundles are lashed, and the men eat – 1![]() cans of soup each – then everyone washes himself with snow. At 6 we set off. At 11 we take a 2-hour rest-break, then we keep hauling until 4 a.m. At the rest break each man gets 1

cans of soup each – then everyone washes himself with snow. At 6 we set off. At 11 we take a 2-hour rest-break, then we keep hauling until 4 a.m. At the rest break each man gets 1![]() portions of chocolate and half a can of water. We can't thank Kluge in Prague enough for the chocolate; it is excellent and I can't recommend it enough as a healthy, nourishing change from the eternal, monotonous soup. As soon as we have reached our stopping place the tent is stretched over two sledges and beneath it the stove is lit. Everyone retreats to the boat as quickly as possible, changes his stockings, wraps himself in his furs, and after supper and a mouthful of water stretches out in his sleeping bag. As the sleeping, dressing and dining room for 8 people the boats are somewhat cramped, and one often has to assume the most remarkable positions in order to put on or take off an item of clothing. It is often really bad for me, especially, with my long limbs. The ridge of the tent is only about 4 feet above the keel. I have the worst spot in the entire boat, on a board laid over two seats. My head lies right next to the rear tent door, and a strong draught blows in.

portions of chocolate and half a can of water. We can't thank Kluge in Prague enough for the chocolate; it is excellent and I can't recommend it enough as a healthy, nourishing change from the eternal, monotonous soup. As soon as we have reached our stopping place the tent is stretched over two sledges and beneath it the stove is lit. Everyone retreats to the boat as quickly as possible, changes his stockings, wraps himself in his furs, and after supper and a mouthful of water stretches out in his sleeping bag. As the sleeping, dressing and dining room for 8 people the boats are somewhat cramped, and one often has to assume the most remarkable positions in order to put on or take off an item of clothing. It is often really bad for me, especially, with my long limbs. The ridge of the tent is only about 4 feet above the keel. I have the worst spot in the entire boat, on a board laid over two seats. My head lies right next to the rear tent door, and a strong draught blows in.

Set off at 6 p.m. and travelled until 10.30. Payer began with his old petty jealousies again. He is again in such a rage that I am braced for a serious collision at any moment.Footnote 18 It is all due to the trivial matter of a bag of bread: he insisted that he had had to transport it too often; in front of the men he made suggestive remarks that I could not pass without a reprimand. I told him that in the future he should watch such expressions, since otherwise I would reprimand him publicly. At this he flew into one of his rages and said that he could clearly remember that a year previously I had threatened him with a revolver, and assured me that he would forestall me in this, and even declared quite openly that he would be out to kill me, as soon as he saw that he wasn't going to get back home. Then he reproached me with his stories that he has repeated a hundred times; he accused me of ingratitude because he had always gone back to the ship in the past few days and fetched luxury items. In reality he has done this purely out of selfishness, in order to sleep peacefully on board, and by his own admission in order to be able to feed like a pig. He said he had been hauling a barrel of alcohol behind us, while we were already hauling 60 lbs of alcohol. For two years now Payer has been riding Lusina, for the sole reason that, as bosun, he functions as my executive. Yesterday, as we were hauling he dared to make remarks about him out loud, while I was hauling beside him. A direct censure does no harm, but such remarks are designed only to irritate and to provoke dissatisfaction. And this must be avoided at all costs. However Lusina is not pulling as much as he might do given his great strength, and I have already taken him to task for it. It is a fact that after a day's work he is always dead-tired; he is a particularly poor walker, and moreover he has a defective toe. Raw, frozen bear meat is to be recommended; but it does provoke thirst.

27.5. Hauled until 3 a.m. then pitched camp for the night, since some minor work had to be done on the hauling ropes for the sledges. A fresh NW wind; temperature −6°R; unpleasantly cold once one stopped hauling. Towards the end atrociously bad going; in places had to haul on hands and knees due to the deep snow. Set off again at 6 p.m.; made good progress with moderately good going until 10 p.m.; rest-break from 10 to 12. One can of water and a can of somewhat warmed tea for everyone.

28.5. Worked, with horribly bad going until 4 a.m. Since yesterday evening have advanced a good mile. We are no longer far from the island and close to the large pressure ridge. The latter had formed along a reef that runs northeast from the eastern end of the island. There must have been some terrible ice movements here during the winter. (It has emerged that for 3 days Payer has been hauling over macaroni, etc., i.e. nothing but luxury items. I accepted nothing but a small barrel of alcohol). Payer today was singing a much milder tune. The ship is out of sight today. From last night's camp it lay about 4![]() miles away on a bearing of NE

miles away on a bearing of NE ![]() N.Footnote 19 We are all dead-tired today; such strenuous marches are too much. Set off at 6.30; reached the island at 9.30. It is a bump of snow, from which isolated rocks poke out. Its long axis is aligned roughly SW – NE, about 1

N.Footnote 19 We are all dead-tired today; such strenuous marches are too much. Set off at 6.30; reached the island at 9.30. It is a bump of snow, from which isolated rocks poke out. Its long axis is aligned roughly SW – NE, about 1![]() miles long.Footnote 20 Found a piece of driftwood and made some warm tea. Rested until midnight.

miles long.Footnote 20 Found a piece of driftwood and made some warm tea. Rested until midnight.

29.5. Friday. From midnight till 3.30 p.m. made a steady march across the island with good going. For the first time hauled boats and sledges in 3 parties. Approximate direction SWbW; 2 miles during the day. Found some driftwood and for the first time drank water ad lib. 2 miles southwest of the island there is a fairly large polynya, but it lies too far out of our way. Before midnight we passed the icebergs for which we were heading SSW from the ship. Close up these apparently colossal ‘ice mountains built for eternity’ have shrunk mightily. One is so badly deceived in the ice. What has tired us most recently is thirst. Today we had enough to drink and despite this serious march we are far from being so tired. A biting, cold NNE wind, which we can tolerate only by keeping moving in the open. Due to the vicious wind and the drifting snow we got under way only around midnight.

30.5, Saturday. Hauled until 4.45; fresh N wind; bitterly cold. Froze my left foot and had to have it rubbed with snow for 2 hours.Footnote 21 When I was carrying out this operation in Payer's boat and then was looking for a pair of skaler (Norwegian reindeer-skin shoes), I discovered that Payer is hauling an entire depot of delicacies, pure luxury items, bottles of fruit, cheese, etc. I won't make any use of this accidental discovery, but such selfishness fills me with disgust. Since we left the ship I haven't consumed a single piece of bread more than any of the seamen. This is the apparent self-sacrifice associated with hauling a depot [from the ship].

Set off at 6; initially good going towards the SSW, then we had to clear a route with shovels and picks. We hauled until 11. During the night a bear came near the boats; PekelFootnote 22 kicked up a row, but everyone was so sleepy that nobody paid any attention. Pekel is too alert; he barks at every bird and hence nobody pays any attention to his barking any more.

31.5. Sunday. Set off at 7.30 after some warm tea. Initially the going was good, but later terrible. Many cracks that had drifted up; often sank waist-deep. Wanted to take a rest at 3 to celebrate Sunday, but we stopped only at 4.30. The polynya is not far away, but I intend avoiding it. We still have too much of a load, to be able to launch the boats, and for the time being can't throw away any provisions, since we would miss them in the autumn. Moreover the ice is still lying too close-packed; with our heavily loaded boats we would be in constant danger of being crushed. There must be very much open water to the W; a dark water-sky in that direction. We have now become accustomed to the daily schedule. Initially one never knew whether it was daytime or nighttime. With the fresh NE wind it is still bitterly cold. Especially in the evening before we start work and before we have washed. We've reserved a small box of sample chocolate for Kluge and Co. If it is at all possible I will take it back south; we can't show enough gratitude to those gentlemen. It is remarkable that we are all most tired before midnight and become fresher only after the rest-break. Around 10 I could collapse from fatigue. By 4 I am relatively fresh. The dogs are now quite worn-out. After a day's work, there is almost no help for Jubinal. They get a daily ration of 2![]() lbs of pemmican and 1

lbs of pemmican and 1![]() lbs of bread. Our appetites are increasing frighteningly; earlier there was always soup left over but now it is consumed to the very last drop. (Payer has been giving me an earful of complaints that the soup should not be eaten with pemmican; it is so excellent that we lick the last drops from the can. The only unpleasant aspect is that due to having been sitting for a long time on deck the fat in the pea sausage has become somewhat rancid). To celebrate Sunday we hoisted the flag at 3 p.m. Shot bear No. 64;Footnote 23 wakened at 4. Celebrated Sunday with a bear stew. It is frightening how much I can eat now; I'm never totally replete! Sunday rest until 7, then cleaned the boats. checked over the sledges and their loads etc; set off at 9 o'clock. Sun visible at times. Calm.

lbs of bread. Our appetites are increasing frighteningly; earlier there was always soup left over but now it is consumed to the very last drop. (Payer has been giving me an earful of complaints that the soup should not be eaten with pemmican; it is so excellent that we lick the last drops from the can. The only unpleasant aspect is that due to having been sitting for a long time on deck the fat in the pea sausage has become somewhat rancid). To celebrate Sunday we hoisted the flag at 3 p.m. Shot bear No. 64;Footnote 23 wakened at 4. Celebrated Sunday with a bear stew. It is frightening how much I can eat now; I'm never totally replete! Sunday rest until 7, then cleaned the boats. checked over the sledges and their loads etc; set off at 9 o'clock. Sun visible at times. Calm.

1 June, Monday. Hauled until 11.30 then rested until 1, then hauled again until 4. Latterly terrible going through high hummocks; in total covered about ![]() a mile southwards. At the rest-break there is now always warm tea or grog, until Payer's supplies of alcohol are used up.

a mile southwards. At the rest-break there is now always warm tea or grog, until Payer's supplies of alcohol are used up.

6.30 p.m. set off; fine weather; fog. After crossing a high ice ridge we ran into nothing but shattered ice, the intervals between which are filled with lightly frozen slush. Passable neither on foot nor by boat. This stuff extends uninterrupted from ENE to S and W as far as one can see. Have to go back and attempt to reach the large polynya further west. As the melt begins the conditions will probably become very favourable here. Down here near the island and its reefs it must have been terribly active during the winter. We are now between immense pressure ridges. We would have been in trouble if we'd drifted into this area in the fall; the ship couldn't possibly have survived here. Hauled the boats and sledges back; rested until 10 o'clock.

Made a long reconnaissance.Footnote 24 The solid ice ends towards the west and south in a high ridge, that becomes lower only towards the island, to the extent that we can get the boats over it. Beyond this ridge, from the SE there is nothing but ground-up sludge, but it is too closely packed for the boats to be used. We have to head back close to the island in order to wait for some change on solid ice. Our surroundings are so criss-crossed by cracks that with the first storm it will all open up. We can't risk taking such a chance with the boats; the boats and sledges would not survive together. On the whole conditions are favourable for the immediate future, but for the moment we can only wait. The first persistent melt will produce open water.

2 June, Tuesday. Calm; fog. Backtracking along our old track until 3, then a rest-break. Our daily provisions ration is now set at 11 lbs pea sausage or ground, dried meat, 15 lbs boiled beef, 8 lbs. pemmican, which is never totally consumed, 8 lbs of bread, 1 lb. flour and 35 rations of chocolate.

If there is bear meat, preserved meat is consumed only in small quantities; we consumed the bear from the day before yesterday totally in 48 hours. Generally something is left over from the provisions that are issued, since the kettles are too small and the soup would become too thick.

Fine, warm weather, calm; the sun is shining brightly; much fog to the SW. Set off at 6 p.m., back-tracking. The slush has opened up somewhat, and is forming individual lanes. We will now set up our base a quarter mile from the edge of the solid ice, in order to be able to take advantage of every favourable opportunity. However we are risking drifting away with the ice, if the ice happens to break up fast, but if we were to return to the island we would be too far from the polynya, in order to quickly take advantage of any possible favourable circumstances.

At 9 p.m. we reached a suitable spot and stopped. Shared out the last delicacies, 2 cans of milk.

3 June, midnight. [one line illegible]. My bed is a board that serves as sideboard, dining table and writing desk on one side; turned over it serves as a carving board when bear meat is being prepared for the bear stew, as amputation and bandaging table for the doctor, or as work table for the various improvised workshops. Kepes and Klotz lie forward in the bow, both as motionless as rocks; aft of them Latkovich and Orasch between two benches; the legs of the first two extend above their heads over the rowing bench. As compared to the others Lusina and Vetserina occupy a drawing-room; they occupy the space between two rowing benches. Right aft in the pointed stern of the boat is my palace. During the day I can sit only with my legs pulled right in; at night I withdraw onto my 9-inch-wide plank that is laid over the rowing benches and the sleeping Lusina. My sleeping and living space is not very enviable. My unusually long legs often have to be forced into the most remarkable contortions; at night I hear about their cold, heat and thirst from the others at first hand. In a cold wind I freeze to the bone; in bright sun and calm it's like being under a tin roof. The men's health is good; a few slight cases of diarrhoea have cropped up, but quickly disappeared (Skarpa suffers badly from his incontinentia urinae, as a result of which his entire perineum is eaten away.) Set off after midnight and hauled boats and sledges about 500 paces further away from the edge of the solid ice, clear of any cracks that might rapidly open. We have to stay here now until there is a change in the ice. Nearby there is a disintegrated iceberg; the remnants of it would cost a fortune in Vienna. A midnight altitude gave a latitude of 79° 45′ 50″; according to this we are only 5![]() [nautical miles] from the ship.Footnote 25 During the night I reached the decision to opt to remain lying quietly here, and to wait until conditions are sufficiently favourable that we can risk launching the heavily loaded boats, to return to the ship with a strong crew and to fetch our jolly boat. Then we'll be able to venture among the ice as soon as the first leads open. I'll leave the boats and sledges with Brosch and 11 men on the island, and go back to the ship with10 men.Footnote 26 We can be back in 4 days with the boat, fully equipped. For this purpose everyone was wakened at 12 o'clock; at 2.15 back near the island. Hauled until 6, then rested until 8; then hauled until 11 o'clock.

[nautical miles] from the ship.Footnote 25 During the night I reached the decision to opt to remain lying quietly here, and to wait until conditions are sufficiently favourable that we can risk launching the heavily loaded boats, to return to the ship with a strong crew and to fetch our jolly boat. Then we'll be able to venture among the ice as soon as the first leads open. I'll leave the boats and sledges with Brosch and 11 men on the island, and go back to the ship with10 men.Footnote 26 We can be back in 4 days with the boat, fully equipped. For this purpose everyone was wakened at 12 o'clock; at 2.15 back near the island. Hauled until 6, then rested until 8; then hauled until 11 o'clock.

4 June, Thursday. By 2 a.m. we'd got back to our campsite of the 29th. We had been sweating away for all 5 days in vain. The polynya has closed completely again. Calm; warm in the sun but still 3–4° below zero in the shade. Since yesterday we've been engaged in a real forced march. We covered the distance that took us 12 hours previously, in only 8 hours. The reason that this was possible was that the sledges ran much better on the trail that we had travelled already. Our existence is now that of draught animals. Eating, drinking and sleeping are the brighter aspects of our existence. I constantly have to think of the draught oxen that lie stretched out on the Giuseppi Quay [Molo Giuseppino] in Trieste, contentedly chewing the cud. Almost more unpleasant than the steady pulling is ploughing through knee-deep snow. I find it terribly tiring; at every step one breaks through the surficial hard crust and then forcibly pull one's foot out. This type of progress is much tougher than any mountain climbing, since one has to raise one's foot much higher to clear the snow surface.

By 2.30 p.m. started back on board with 10 men. Reached the ship at 6.30 after a brisk trek. (I found the ship in total disorder. The hold broken open; the lids missing from the provisions boxes, their contents scattered, the cabins full of filth, rags, empty cans, bottles etc., although Payer had left an hour before us with the dogs to tidy things up. All those little delicacies that we had been looking forward to, milk, fruit etc., had been consumed. During his visits to the ship Payer must have enjoyed an unbelievable blow-out, since we had left vast amounts of these things. Despite this, there was still so much on board of what people in our position might consider delicacies, that we soon had all gorged ourselves.) We immediately lowered the white jolly boat to the ice and began to refurbish it. Organizing a canvas roof, caulking some of the hull and sealing it completely occupied us until midnight on Friday. On Saturday afternoon I fitted the boat out, and at 2 a.m. on Sunday 7 June we left the ship again, probably for the last time. During the entire period we had snowsqualls with a fresh NE wind. Our old route, that could be identified on the outward journey only with great difficulty, could now be detected only by paying the closest attention and by applying true Indian tracking skills. One man always had to walk ahead, since if one strayed left or right from the hard-frozen trail one would sink deeply. We often had to wait 15 minutes until our tracks were found again. Despite these impediments we reached the boats at 10 a.m. If we had not found our old trail, it would have taken us at least 20 hours. We were all glad to be back again; our sojourn on board had given us nothing but bloated, upset stomachs. We had even slept badly on board; after I got back to the boats I slept better, despite my cramped position, than during the three nights on board. During our absence Brosch had built a cairnFootnote 27 and had deposited in it one of the documents we had brought with us. The weather had been so persistently bad that they had not been able to get a view. They had found quite a lot of driftwood under the snow, including a good log 30 feet long and 18 inches thick. A bear had appeared but had stayed out of range. The old polynya had stayed fairly stationary. I visited it with Klotz today. We waited in vain at a seal's hole for the occupant to reappear.

8 June, Monday. A beautiful day. Warm in the sun, but still below zero in the shade. (Payer laid up with herpes, with a rash of blisters on his chest).Footnote 28 For our further progressFootnote 29 across the ice the provisions were distributed differently, since the weight of boat no. 4 has been added.Footnote 30 Progress had been so tough earlier, how can we manage now! With a gentle north wind the polynya has widened; but the edge of the solid ice is piled so high everywhere that we can't get the boats and provisions over it. Moreover everywhere there is a stretch of half-frozen stuff that has been driven together, a cable in width, across which one can neither walk nor travel by boat. To the west the solid ice is bordered by a belt of quite young ice, half a mile in width, about 3 inches thick and with a light covering of snow, and the outer fringe of this too is in a hopeless condition. I'm afraid that we won't be able to proceed until a strong westerly gale jams the ice solidly together. Our state of health is excellent. Unfortunately no sign of bears.Footnote 31

9 June. Tuesday. Went out on a reconnaissance after midnight to see where we can launch the boats, but everywhere encountered pressure ridges with thin stuff lying in front of them. Northwest wind. The polynya has widened even more. Conditions were favourable for taking to the boats, but one can't reach the water anywhere. Brosch, Orel and I made a long reconnaissance, but found the same conditions everywhere. The best place is still the one I had found first, before we fetched boat No. 4. And we had to go back to our camp of 3 JuneFootnote 32 to wait. Saw a pod of beluga in the polynya; a favourable sign that the ice is passable by boat.

10 June, Wednesday. After midnight made an attempt to haul the light boat over the pressure ridge to the level surface of young ice and across it to the water. We might have hauled the light boat there empty, but were we to try it with the large boats with their boat-sleds they would certainly disintegrate. The polynya now extends to the grounded iceberg in the SSW. (Orel had to move his quarters from No. 2 since Payer's condition is contagious.) Seeing the open water ahead of us, without being able to reach it, is a real torture. Set off at 6 p.m. Calm; cold, down to −4° by 3 a.m.

11 June, Thursday. Reached our old campsite of 3 June at 3 a.m. The polynya appears to have closed completely. The load from sledge No. 3, on which boat No. 4 travels, has been distributed among the other sledges and boats, without it being very noticeable. (Since Payer's condition is contagious, I have cleared boat No. 4 for him and the doctor. As an experiment I have changed places with the doctor.) A fresh east wind, slackening towards evening; cold; down to −5°R. After we got up, hacked a route to the water.

12 June, Friday. Wanted to launch the boats one after the other and check how they carry their loads, but when we reached the edge of the polynya with boats and sledges everything was covered with slush. Had to go back. ‘We can wait,’ says Schmerling;Footnote 33 ‘We have to wait’ is our version. Carlsen given the instructions in Norwegian. A warm day; in the evening a cold ENE wind that quickly strengthened; bitterly cold. Cut a dock in a floe of young ice and launched boat No. 3 (with its load) in it. It leaked quite a lot, but I think its seams will soon tighten of their own accord. It rides well in the water with 800 lbs of cargo and 5 men, but they have terribly little room. Payer is feeling better.

13 June, Saturday. A strong ENE wind; complete overcast. The ice is drifting with this wind as usual and is ridging-up the solid ice edge. Instead of the brash-ice as earlier, it is now seriously heavy ice. We wanted to place one of the whaleboats in the dock too, but when we got over there it was already destroyed. In order not to miss every opportunity to make progress, I am now sending a man to the ice edge every 4 hours to investigate ice conditions. Now that we would have had plenty of firewood and time to make a decent meal, there was no sign of any bears. The temperature is constantly below zero. It was two years ago today that we left Bremerhaven. Time has passed incredibly fast; it often seems to me that it has been just that same number of months. My writing represents a sort of thermometer: the worse it is, the stiffer my fingers are and hence the more uncomfortable my position at that moment. The last trip back to the ship resulted in so much tobacco for the men, that the present stoppage can be made somewhat more bearable by smoking. My bed-mate, that honest child of nature, Klotz, is constantly blowing smoke from his dubiously smelling and wheezing pipe under my nose. We are now wreaking havoc among the last delicacies that remind one of the ship. For example we still have some metal kegs of rum; I now have them drained into our tea. All that is left now is a keg and 7 bottles for medicinal purposes. After 4 o'clock an ENE gale, which slackened towards evening and swung round to become a fresh SSWerly. Ice closed up. Cut a new dock in the new floe.

14 June, Sunday. After midnight hauled Boat No. 1 into the new dock and loaded it normally. Just as the boat was fully loaded the ice began moving, the young floe was shattered and the dock destroyed. We hauled the boat and its cargo to safety just in time. A fresh SSW wind; −1.5°R. (Klotz is entertaining me with his unsophisticated stories from the Tyrol. His references as to his own life are comical. His breakfast would be: coffee and bread; 2nd breakfast: mug of wine, bread, sausage; lunch: soup, 2 dumplings, roast meat with salad, 2 mugs of wine; supper: meat and bread and a mug of wine. His pay 1 fl. 80 kr. He was simply a slightly superior day-labourer, sometimes a guide, sometimes a poacher, sometimes a prospector, sometimes a logger; he also functioned as doctor, hairdresser, etc. in Passeier.

What comes out of his mouth is true to the last detail. He has a great deal of natural common sense, but it is corrupted by a mountaineer's prejudices. He must be a respected personality in Passeier. At night he snores horribly in my ear. Hoisted the flags; this is the only sign that it is Sunday. 9 a.m., bear No. 65 killed.Footnote 34 It appears that the Wendl carbines are better for bear than the Lefaucheux with a calibre three times greater. Today's is the second bear that was shot with a Wendl and dropped dead with the first shot. Abundance of bear meat. Stew instead of our midnight chocolate and bear instead of boiled beef. Pea sausage and pemmican discontinued. Water sky to the west; the solid ice edge cemented together.

15 June, Monday. Strong SWerly. Lying constantly in the boats; all my bones are aching from lying crooked for too long; in addition bitterly cold, although it is only −2°. To pass the time the bear meat is cut up into the smallest possible pieces for supper and breakfast. It seems that when the bear meat is not fully cooked it produces diarrhoea, and since we don't have enough alcohol to let it cook any longer, we have to cut it up quite finely. Anyone seeing the amount cut up finely for 7 people would be amazed at these mountains of meat. And despite this when the bowls are emptied one still hears the meaningful scraping of spoons that accompanies the search for the last traces of food. During the day the wind swung into the south; melting; a heavy snowsquall; ice situation unchanged.

16 June, Tuesday. In our conversation about FiumeFootnote 35 I realised by chance that I hadn't paid at the hotel. Ice situation unchanged; calm.Footnote 36 In the evening a beautiful, big polynya to the south; to the west to where we are heading, everything is jammed solid.

17 June, Wednesday. Calm. Was reconnoitering for 3 hours, trying to find a route to the polynya to the S. The best route is our old route with a minor deviation towards the end. But to get there we'd have a very tough day's trip, during which time it might close to the south and open again to the west. It is purely a game of chance. But, since we prefer to be moving than resting, I propose that we set off around 9 a.m. along our old route, if conditions have not changed before then. We can't remain in this inactivity any longer. Calm in the forenoon; warm; the polynya is unchanged.

11 a.m. Got under way; at 4 we reached the spot from where we turned back on 1 June. Cooked a meal there and rested for 2 hours. Then broke a route through the ice edge to a floe lying in front of it, and reached the water across it around 8 o'clock. The provisions distributed among the boats. Boats launched.Footnote 37 Sledges placed upon the boat-sleds; hoisted our flags and at 11 o'clock sailed away with a fine NE wind. The boats are heavily laden, but not overloaded; the jolly boat is in the best situation, and could carry a few more centners.Footnote 38 Boat No. 3 is in the worst situation [half a line of text missing here] we're hauling the jolly boat and [text missing]. The sledges and boat-sleds towed by the boats make the latter quite unmanœuvrable. As long as we are towing them, we'll miss numerous good opportunities. But on the very first day I can't discard the sledges and boat-sleds, since we may still have to cover some distance across the ice.

18 June, Thursday; NNE wind. Sailed across the polynya which is about 2 miles wide and then about another mile through loose ice. But then, for the moment we could go no further so we hauled the boats up onto a large floe and pitched camp for the night. At 6 a.m. had a meal. Wakened at 4.30; west wind. Polynyas all around us, but close ice to the south. Hauled the boats to a polynya and launched them. But had to haul them out again immediately, but before they were loaded, because the polynya was closing very rapidly. We still have much too much in the way of provisions, to risk embarking on the narrow leads; before we had unloaded enough to haul the boats out, they might be crushed ten times over, when the ice starts moving. In order for us to be more mobile I've even had the boat-sleds demolished.Footnote 39 We have to retain the sledges for a while longer; but we will load them on the boats instead of towing them. Wind has gone into the SSW. There's quite a lot of life in the water. Seals and birds of every species; yesterday a walrus even hauled out on the ice edge close to the boats, the first we have seen here; it stared at us in astonishment. With the wind freshening, and with a persistent snowsquall, the ice closed up even more; we could go no further. We had to crawl under the tenting, soaking wet. While we slept we were drifted a good distance east and also somewhat north. Now, in the evening Wilczek Headland [Mys Vil'cheka]Footnote 40 bears NbE, about 8 miles away. Today we are again treating the night as our day; it is still too cold at night to sit quietly in the boats.

19 June, Friday. Persistent snowsqualls. Wind slackening; 4 a.m. a light north breeze, slowly freshening; ice broken up everywhere, but no leads. In order to at least be doing something, I got us moving at 6, and crossed to the nearest floe with boats and sledges. South of it, however, everything is so broken [this last paragraph stroked out in the original].

I've missed a single day's entry and have lost count so badly due to the switch from day to night and due to our irregular sleeping, that I have lost an entire day. Only now can I understand how easily the whalers can get confused as to the date. Day and night are indistinguishable, and one very rarely sees the sun. The time therefore means nothing; repeatedly somebody in the boats throws out the question, ‘Is it morning or evening? Persistent snow flurries with a fresh SSW wind. Close ice. Lay the whole day, soaked, in the boats. Wind slackening in the evening, then calm.

20 June, Saturday. A light northerly breeze arose during the night; ice still close. To avoid being completely idle I crossed to the next floe, but found the ice at its southern edge so shattered that we would have been doing nothing but continually ferrying from floe to floe. But this would take too much time without making any significant progress. I prefer to save the men's health and strength until July, when we can really count on truly favourable conditions for the first time. If we ever get completely soaked, our clothes will never dry completely again. Thus far we have found everything as unfavourable as possible. We've been away from the ship for a month, and have not even covered 10 miles. (God grant that it will improve, otherwise we are lost!) Fortunately we have a north wind which has driven us a good distance southwards over the course of the day. To cover the 200 paces from our campsite to the southern end of the next floe, we've laboured for 4 hours. Without the boat-sleds, hauling the boats through the deep snow is really tough; only the jolly-boat can be moved easily. I'm letting each crew haul its own boat, so that each crew learns to be independent of the others. The hazard of ferrying across leads, that are often barely wider than the boat's length, is that one is hazarding the boat each time. If the lead closes while the loaded boat is in the water, it will be crushed. (Payer's herpes has returned; Kepes is lying suffering from a headache and fever. I hope that Payer does not infect others! Otherwise our state of health is excellent.) So as not to miss the slightest opportunity for advancing, I have a man standing watch day and night now, and he is to alert me to any change in the ice. From today I'll issue only 1 cake of chocolate per head, instead of 1![]() .

.

21 June, Sunday. A freshening west wind; ice conditions practically unchanged. (The doctor insists that he and Latkovich, who is also feverish, are suffering from hunger fever. At the same time he can see that the entire crew looks so well-fed and healthy, that it is a real joy. I have bet him that given our present diet hunger fever is an impossibility). Shot a small seal that went straight into the pan. Unfortunately it is so small that each man's share is not very large. The times when one carefully removed the smallest piece of fat, are long gone. Bones and all, with the exception of the intestines and the blubber, go into the pot. We appear to be drifting quite respectably again; Cape Wilczek [Mys Vil'cheka] is now barely visible from the highest hummocks, bearing NbE; the ship is no longer visible. It is pleasant to sleep at night; the day is more enjoyable then; one can see the sun more often, without it becoming a nuisance from excessive heat. During the day the temperatures are fluctuating around zero, while at night the temperature is still dropping to a few degrees below freezing. Have found raw seal blubber with some salt quite tasty; there is scarcely any perceptible fishy taste.

22 June, Monday. A fresh west wind; occasional openings in the ice that quickly become covered with brash, however. Can't make any progress with the boats. Proof that the men are not suffering from hunger is the fact that half a pot of soup was left over from the small seal which perhaps weighed 15 lbs without the blubber. (Kepes well again; he realises that his diagnosis of hunger fever was erroneous.) In order to be ready for anything, I've started eating a respectable portion of raw seal blubber. It goes down quite well with bread. Between 7 a.m. and 3 p.m. waited for seals at a water-hole for 5 hours; fired twice but missed. A seal is difficult to shoot; it shows only its head, and one must shoot it through the head in such a way that it is killed instantly, otherwise it dives. Generally it falls into the trap out of curiosity; any unusual noise will bring it to the surface. I've never seen these small seals lying on the ice; how then can a bear catch one, since it has no breathing holes, but lives in the polynyas? This is a puzzle to me. (Where have the bears vanished to now; there is no sign of any. Are they perhaps hunting nesting birds, or do they avoid the smaller floes among which we are now blundering?)

23 June, Tuesday. Fresh WSW wind; brightening in the afternoon, lulling one into a false sense of optimism. Ice has opened somewhat; occasional polynyas, but they are not interconnecting. 7 p.m., ferried across a short polynya, then across a large floe to a new polynya. Ferried across it, then across a fairly small floe to reach another polynya. While we were hauling across the floe the access to the water on the other side closed. Stopped to cook and rested for 2 hours. Then back again and across another floe into the larger polynya. Crossed it and camped for the night on a fairly large floe; at 8 p.m. the polynya behind us closed. Seal blubber agrees with me extremely well. The going across this floe is significantly better than on the solid ice. The somewhat moist snow is significantly more favourable than the earlier dry snow. The boats are taking a beating from this work.

24 June, Wednesday. A light southeasterly breeze. Almost no polynyas to be seen. Crossed a large floe and at 2 o'clock were forced to stop at its southern end. Before we started Orel shot an unusually large specimen of a Phoca groenlandica. Footnote 41 Roughly dressed it produced over 150 lbs of boneless meat. We could take only a very small portion of the blubber that was a good 4 inches thick. It is astonishing what enormous quantities of blood are possessed by a seal. While the carcass was being skinned the blood spurted out several feet in every direction from a large number of fine veins, although the majority of the blood had run away in small streams from the bullet wound and from the incised stomach. (Since Payer, Kepes, Latkovich and Stiglich are unfit, we had to haul the whaleboats and their provisions with five men.) Fortunately the sledges are hauling easily in the semi-soft snow and on going that is very good in places. The masses of snow such as had accumulated near the land, no longer occur here. In terms of strength, the sledges are excellent; they withstand an enormous amount of punishment.

25 June, Thursday. The ice ahead of us is too shattered and close-packed to allow us to ferry across. Will have to wait for a change. Around noon the wind swung into the NE with heavy snow. Today cooked with blubber for the first time. To save the wicks we threw some wood shavings and some old spun yarn into the blubber and lit it. Since conditions are so extremely unfavourable for boat travel I am bracing myself for reaching Novaya Zemlya only very late in the year, and am even thinking of possibly having to winter at our depot there. For this reason I am watching as meticulously as possible that we save every little thing, as far as possible. Naturally a wintering would be a matter of life and death, but we have to keep the possibility in mind; hauling sledges across the ice floes is hardly worth the effort; the few miles that we thereby gain are quite insignificant in terms of our purpose. The lightest breeze carries us in the direction we want more than the most strenuous day's work. And in so doing the boats take a terrible beating. Hauling them out and launching them a few times ruins them more than a week's sailing. Hence hauling the boats can only be of importance, if it involves getting from one extensive polynya to another. And I expect such conditions only a month from now. Now the ice is lying much too closely-packed. In order to advance one mile we have to ferry across a large number of leads, that are either filled or closed with brash-ice, while both sides are churned up. No channels are to be seen in any direction; the only water we can see are small pools. (Kepes and Latkovich are again seriously off-colour; hunger is still not a problem; today a very thick seal soup was not completely consumed; everyone had enough with his usual 1![]() cans full, even our biggest eater, Orasch.) Several are following my example of eating seal blubber, and find themselves feeling very well as a result. With every passing day I increasingly prefer this food; it seems as if I am eating bread and butter. Either my taste buds are completely dulled, or this really is the case – I can't decide. But as long as the blubber is fresh I can't detect the slightest unpleasant taste; for me the taste is that of a very pure lard.

cans full, even our biggest eater, Orasch.) Several are following my example of eating seal blubber, and find themselves feeling very well as a result. With every passing day I increasingly prefer this food; it seems as if I am eating bread and butter. Either my taste buds are completely dulled, or this really is the case – I can't decide. But as long as the blubber is fresh I can't detect the slightest unpleasant taste; for me the taste is that of a very pure lard.

26 June, Friday. The wind swung into the N, then NW; the ice is opening a little. Got moving at 7 a.m. Launched and hauled out three times. Forced our way for a distance through thick brash. The sledges are such a terrible impediment; if we carry them on the boats we can't row; if we tow them we make little progress and no progress at all through the brash. Stopped for a rest at 3 a.m. on a large floe. For the first time since we left the ship we got a good sun's altitude at noon; this gave a latitude of 79° 41′. Hence we are only 10 miles from the ship, although we've been on the road for 36 days. We haven't seen any land for 6 days; it has been hidden from us by the intervening fog from the large polynya; I think we've been set far to the east. If conditions do not change entirely during the next few months, we are lost. I'm often amazed at myself, in light of the calm with which I contemplate the future; I sometimes feel as if I'm not involved. In the extreme case, my decision is [a line of text missing] sailors, means a lot to me; my entire thoughts and wishes are concentrated on this. I can now appreciate how indifferent a person can become to danger. A bear showed itself during our rest-break, but did not come any closer.Footnote 42 We are now using blubber to heat water for tea; but it takes a dreadfully long time for the water to boil, over 2 hours today. Today we had a demonstration of how changeable conditions are in drifting ice; if we'd waited an hour, a channel would have opened, and we would have saved ourselves two hours of hauling. In the afternoon we got across the last polynya with very little effort. Five minutes later and we would have had to go back. The seal meat has affected my entire boat's crew; Kepes and Latkovich are finally better, but on the other hand Lusina, Palmich and Orasch are suffering from diarrhoea. Very unfortunately, while we were hauling the boats out the last time Palmich was struck by his old knee problem (rheumatoid arthritis). Of the seven only 4 will be able to haul tomorrow.

27 June, Saturday. Strong NE wind; set off at 5.30; crossed a floe, then launched into a polynya, across which we sailed for 2 hours, approximately SbW. At 9.30 we found the ice closed up and stopped for a rest. Sun's noon altitude gave a latitude of 79° 39′; hence since noon yesterday and with favourable conditions we've advanced only 2 miles! I'd counted on at least 5. The northeastFootnote 43 wind must have driven us north. In the afternoon we crossed a water-hole and two floes. At 3.30 cooked our meal. Still occasional polynyas of limited extent in sight, but not interconnected. Today our seal meat is finished; we've been eating it for 4 days and have saved 90 lbs of provisions. Seal meat appears to be very hard to digest; it has to be well cooked. The cases of diarrhoea have ceased since the forced rests have ended. With work like this one could even digest pebbles; today Latkovich was hauling again but ran out of energy; Kepes is like a log of wood, and can't move for weakness. Palmich is working, but I'm allowing him to work only a little. Stiglich's wounds are festering at the surface due to starting to haul prematurely.

28 June, Sunday. Fresh NE wind with snow-showers, but slackening in the evening. Since we left the ship we haven't had a single day without some snowfall. What's the good of this melting weather, when double the amount of fresh snow falls! Got under way at 5.30 a.m. Traversed a small channel, then hauled across a small floe, which took us to a small polynya. As we were crossing the floe, a piece of planking in my boat was stove in. Repaired it immediately. While carrying out this repair, access to the polynya disappeared. Waited for an hour, then ferried across and crossed a fairly large floe. Perhaps a mile of progress southwards during the day. (I have an unpleasant sore that bothers me a lot while I'm working.)