Background

On 19 January 1854, the British Admiralty declared that the officers and crews of the ships comprising the 1845 Franklin North-West Passage Expedition, Erebus and Terror, were considered dead (The London Gazette, 20 January 1854). Amongst their number was Francis Rawdon Moira Crozier, captain of HMS Terror and the Expedition’s Second, to whom command had devolved upon the death of Sir John Franklin on 11 June 1847. Thereafter, Sir James Clark Ross was tasked at short notice by the Royal Society to write a memorandum of Crozier’s services to be printed in its obituary. Ross was Crozier’s closest friend (Ross, Reference Ross1982). They had served together on three out of four of Sir William Edward Parry’s Expeditions, Crozier had been Ross’s first lieutenant aboard HMS Cove in the Arctic in 1836, his Second on Ross’s 1839–1843 Antarctic Expedition, and had acted as best man at his wedding on 18 October 1843 (Ross, Reference Ross1982). In a letter to Sir John Franklin’s daughter, Eleanor Gell, dated 20 March 1855, Ross expressed his frustration at being permitted only 12 lines to set out the services of “one I so truly loved” (Ross, Reference Ross1855, p. 2). He further noted that, but for the short timescale permitted to him, he ideally would have wished to first liaise with Crozier’s family since, “…as it is, I could not tell where or when he was born…” (Ross, Reference Ross1855, pp. 1–2).

In 1856, within the Parish Church where Crozier had worshipped in his native Banbridge, County Down, the survivors of Crozier’s 12 siblings placed a memorial tablet by the celebrated sculptor Joseph Robinson Kirk, R.H.A., which recorded that Crozier was born in September 1796 (no specific date given – The Newry Telegraph, 1 May 1856). Following a public meeting in Banbridge on 13 October 1859, a committee was formed to further the erection, by public subscription, of a memorial to Crozier in the town (The Belfast News-Letter, 14 October 1859). Amongst the Committee’s number were some of those who knew Crozier best – his 41-year-old nephew William; his nephew-in-law and old friend John Henry Loftie, and James Clark Ross (Committee of the Crozier Memorial, 1859a). In the Memoir of Crozier printed by the Committee to further the public subscription (Committee of the Crozier Memorial, 1859b) Crozier’s date of birth was again recorded only as September 1796 and it was this date that later came to be inscribed on the resulting monument itself. Confirmatory evidence for this birth date of September 1796 seems to have come from the youngest of Crozier’s surviving sisters, Charlotte. A short biographical note from her to that effect is now held by the Royal Geographic Society (C. Crozier, n.d.).

A review of the existing evidence

The first biography of Crozier (Fluhmann, Reference Fluhmann1976) proposed that the likely correct date of birth is 17 September 1796 and cited in support an undated note sent by Crozier during the 1839–1843 Antarctic Expedition held in the archives of the Scott Polar Research Institute (F.R.M. Crozier, n.d.a).

Fluhmann (Reference Fluhmann1976, p. 5) found the content of this note to be “almost obliterated” and because it was addressed to “Dear John”, she assumed it was addressed to John Sibbald, at a time in the Expedition when Sibbald was still a lieutenant aboard Erebus (latterly, from August 1842, Sibbald was Crozier’s First Lieutenant aboard Terror) (Ross, 2018).

There the matter rested until, in a contribution to this Journal, Campbell (Reference Campbell2009a) argued that a birthdate for Crozier of 16 August 1796 is far more probable. A contemporaneous reference to Crozier’s birthday was cited in support, namely a journal entry for 16 August 1842 by Crozier’s Royal Marine Sergeant aboard Terror, William Keating Cunningham:

“16th Tuesday Blowing fresh all day. The Captains birth day: all the Officers of both Ships dined with him and Spent the evening. Spliced ‘main brace’.” (Campbell, Reference Campbell2009b, pp. 120–121)

Campbell also re-examined the undated “Dear John” note which Fluhmann had considered and found that it was addressed, on the verso, to “Captain Ross, Erebus”, and was in rather better condition than she had implied. Campbell offered a probable transcription which included the key opening:

“My Dear John I send you D?? Gin and a pound of Pork for my birthday (17th)…”. (Campbell, Reference Campbell2009a, p. 84; Crozier’s emphasis)

From consideration of the overall contents of this note, of Cunningham’s journal as a whole, and from the whereabouts of the ships in each August of the Expedition, Campbell surmised that it had been sent on 14 August 1843. Campbell further mooted:

“The discrepancy in the dates, 16 August according to Cunningham, and 17 of an unstated month, according to the [note], might possibly have been a private joke since the ships had crossed the International Date Line and celebrated 25 November twice in 1841. It is, perhaps, more likely that ‘(17th)’ has nothing to do with the date. Ross and Crozier had first served together in Fury in 1821 and had been firm friends ever since, so Ross was almost certainly well aware of the date of Crozier’s birthday. It might refer to the 17th time they had spent it together… It can only be assumed that ‘My Dear John’ was a mistake on Crozier’s part which he missed in his haste to get the note away. It is difficult to believe the memorials in Banbridge are wrong… since neither gives a date it is not impossible that the actual date of his birth had been forgotten. If it was remembered that he was about a year old when he was baptized, that just might be why September was selected, since he was baptized on 21 September, 1797.”

Ross’s 1855 letter to Eleanor Gell illustrates that, best friend or not, he was uncertain of when Crozier was born. The undated “Dear John” note in which Crozier references his birthday is not an anomaly as Campbell hypothesises but rather is one example of four (F.R.M. Crozier, n.d.a, n.d.b, n.d.c, n.d.d) now held by the Scott Polar Research Institute, none of which bear a date and written by Crozier to “Dear John” during Ross’s Antarctic Expedition. There can be no doubt that the intended recipient of this series of correspondence was James Clark Ross – as we have seen, one item, the undated note referencing his birthday is addressed to Ross on the verso (F.R.M. Crozier, n.d.a). Another can readily be placed in time – a letter in which Crozier (n.d.b) is offering reassurance to the recipient as to his recovery from a sudden, severe illness which befell him on 9 June 1841 at Hobart (Campbell, Reference Campbell2009b, p. 86). It is headed, “Tues. 2 p.m.” and this was most probably Tuesday, 15 June, the same date Crozier’s surgeon aboard Terror; John Robertson (Reference Robertson1841) also wrote to Ross with an update on Crozier’s condition. Due to the reassurance which it offers, its light-hearted tone, and Crozier’s closing remarks, “I am you see getting sentimental. There is however one sentiment on which no change can take place being most faithfully and sincerely yours.” (F.R.M. Crozier, n.d.b., p. 3) it is clear the intended recipient is Ross. “Dear John” was therefore a private, running, joke between them.

The quest for Crozier’s date of birth is further hindered by the fact that no parish register for the key probable period of his own baptism can now be found – unlike that containing those of his elder siblings which remains accessible (PRONI – T2995). The evidence of Crozier’s baptism cited by Campbell (Reference Campbell2009a) is a baptismal certificate filed with the documents lodged in support of Crozier’s Lieutenant examination (TNA – ADM 107/49/116). This certificate was signed by the officiating clergyman, the Reverend Nathaniel Shaw, Presbyterian Minister of Banbridge but it is not contemporaneous, being dated 24 January 1812. Shaw may have been in failing health when he made out the certificate – he died on 3 July of the same year (Linn, Reference Linn1907). He would, however, have known Crozier reasonably well – Crozier attended his Henry Hill School as a boy (Belfast Commercial Chronicle, 24 June 1805; 23 June 1806; 26 December 1807).

The continuing uncertainty as to Crozier’s birthdate is encapsulated by Crozier’s most recent biographer (Smith, Reference Smith2021, p. 24):

“It was at Avonmore House in the early autumn of 1796 that the eleventh child of George and Jane Crozier was born. The precise date of birth is not clear, though it is thought to have been 17 September”.

Further evidence

This note proposes an alternate date for Crozier’s date of birth. Crozier’s father, George, was a solicitor who practised successfully in Banbridge and Dublin. Amongst his clients was Arthur Blundell Sandys Trumbull Hill, 3rd Marquess of Downshire, an Anglo-Irish peer, whose estates in Ireland were vast (PRONI – D671/C/5; Maguire, Reference Maguire1972). In a letter of 14 March 1810, Downshire wrote to George Crozier, evidently in response to an earlier request from Crozier for assistance as to how to go about entering Francis into the Royal Navy (Downshire, 1810). In this letter, Downshire relays that he has spoken to the Earl of St. Vincent (Admiral and former First Lord of the Admiralty), who has agreed to manage the matter. Downshire then asks Crozier to reply immediately, specifically with details of his son’s exact age and his progress in education.

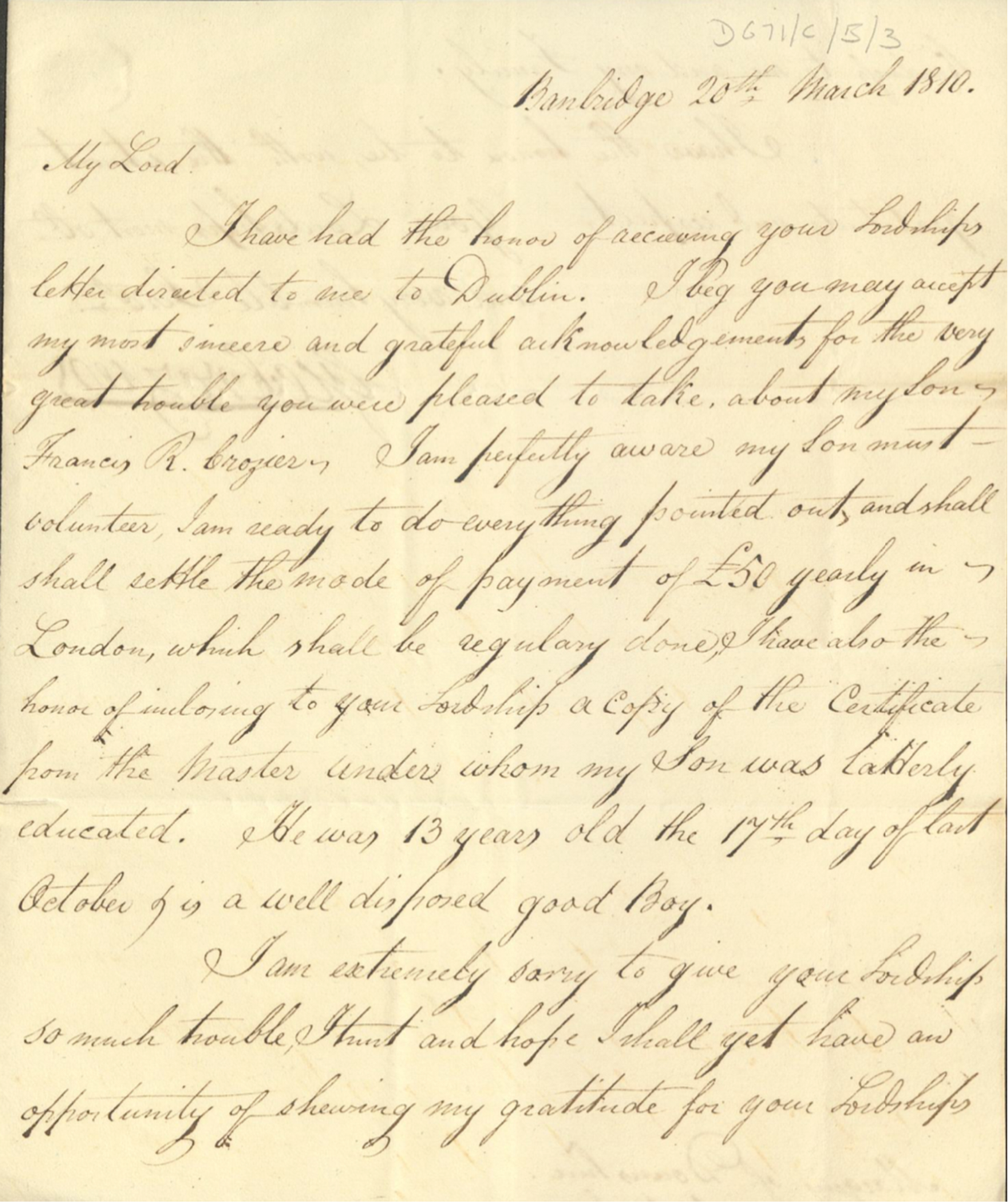

On 20 March 1810, George Crozier sent his response. As bid, he enclosed a copy certificate relating to Francis’s education, and stated “… my son Francis R. Crozier… was 13 years old the 17th day of last October & is a well disposed good Boy…” (G. Crozier, Reference Crozier1810, p. 1 – see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Letter, George Crozier to Downshire, 20 March 1810 (Extract). Reproduced with the kind permission of the Deputy Keeper of the Records, the Public Record Office of Northern Ireland. (PRONI - D671/C/5/3)

Re-assessing the evidence

There are therefore three known possibilities for Crozier’s birthdate – September 1796, 16 August 1796 and 17 October 1796.

The primary source for a date in September 1796 was one or more of Crozier’s surviving siblings, which adds to its credibility. Nevertheless, their recollection was not so precise as to extend to actual identification of the day of birth. Perhaps knowledge of a September baptism was indeed a factor, but the evidence of that baptism – Reverend Shaw’s 1812 certificate – is enigmatic in its own way, having been written almost 15 years after the event, and dating the baptism to the year following Crozier’s birth at a time when more typically only days or weeks would elapse between the two events. It may be that the time lapse and the lack of a contemporaneous baptismal record arise from the political and religious conflict and turmoil which afflicted Ireland (including County Down) at the immediate close of the 18th century (e.g. Pakenham, Reference Pakenham2015; Stewart, Reference Stewart1995).

Cunningham’s journal entry identifying the birthday as the 16 August is of course a contemporaneous record of what was happening aboard Terror. There is, nevertheless, an alternative explanation for the celebration that took place that day in 1842. Immediately following receipt of James Clark Ross’s report of the Expedition’s first 1840–1841 Antarctic Season, and acting upon Ross’s specific request, the Admiralty made a special promotion of Crozier to post-Captain; Edward Joseph Bird, First Lieutenant of Erebus to Commander, and Alexander John Smith, mate of Erebus to Lieutenant (Bell’s Weekly Messenger (London), 9 October 1841). The date of all three promotions was 16 August 1841 (TNA – ADM/196). Subsequently, George Henry Moubray, clerk in charge aboard Terror, was promoted to paymaster and purser at the beginning of September 1841 (TNA – ADM/196). The Expedition did not learn of these promotions until 6 April 1842 when it arrived in the Falkland Islands and the purser of Erebus, having been sent ashore to procure fresh beef and vegetables, returned without mail but with a “Navy List” from which Crozier and his fellows learnt the happy news (Ross, 2018). It can therefore be argued that, on 16 August 1842, Crozier was celebrating not the anniversary of his birth but the first anniversary of his own promotion and that of his colleagues. Accordingly, Cunningham’s journal entries for 16 August 1840 (when Terror was alone in Hobart, Erebus not having yet arrived) and 1841 – that is, the two years before the promotions were known – record no reference to a birthday, an officers’ dinner or any other celebration (Campbell, Reference Campbell2009b, pp. 61; 90). The year after, in contrast (16 August 1843), Cunningham records: “Captain & some of the officers dined onboard the Erebus” (Campbell, Reference Campbell2009b, p. 151) – again no reference to a birthday.

The only known reference by Crozier to his own birthday – the “Dear John” note to Ross cited by Campbell and Fluhmann – gives neither a month nor a year. Since this note is itself undated, any attempt to retrospectively fix when it was written during the Antarctic Expedition must, given its sparse contents, remain speculation.

George Crozier’s letter to Downshire of 20 March 1810, alone amongst the known sources, identifies date, month and year of birth.

Conclusion

Crozier’s contributions to polar exploration and the advancement of science are significant. A Fellow of both the Royal Astronomical Society and the Royal Society, he possessed the greatest polar experience of any Royal Navy officer still on active service at the date of his disappearance. In recent years, his place in the public consciousness has perhaps been more prominent than at any time since the years immediately following his death. He has become a figure of popular culture, a major character in several novels (e.g., Fortier, Reference Fortier2010; McGregor, Reference McGregor2011; O’Loughlin, Reference O’Loughlin2016; Pierce, Reference Pierce2020; Simmons, Reference Simmons2010) – and of a television adaptation of the latter (The Terror – Season 1 – AMC Studios (2018)) – as well as being commemorated in song (Lament for Francis Crozier (Nugent, Reference Nugent2013). In 2022 alone, three scholarly publications address aspects of his life and career (Betts, Reference Betts2022; Knight, forthcoming; Potter, Koellner, Carney & Williamson, forthcoming). The discovery of the wreck of Erebus in 2014 and of Terror in 2016 has only increased interest in him. Amongst the wreck artefacts, observed but as yet unrecovered, perhaps the most tantalising is Crozier’s desk, seemingly intact and undisturbed. Given this significance and resurgent interest, it is important to clarify, if at all possible, the remaining uncertainties of Crozier’s life.

In dealing with the ongoing debate regarding Crozier’s date of birth, George Crozier’s letter merits very serious consideration. It was written only 13 years after the event it dates and, moreover, was written for an official purpose which could not have been of greater importance, specifically in response to the query as to when Crozier was born, and by a person who arguably could not have been better placed to know the truth of the matter.

Conflict of interest

None.