Introduction

It is easy to appreciate how an explorer's hut can provide refuge from an Antarctic storm. Less obvious is the sanctuary that one's own bunk offers from the emotional tumult within such a cabin.

Ten men completed the first over-wintering on the Antarctic continent (17 February 1899–28 January 1900) housed in a hut with internal dimensions of just 5m x 5m. The members of the expedition, with their ages, were as follows:

Louis Bernacchi (24), Australian, astronomer and physicist

William Colbeck (27), British, magnetic observer and cartographer

Kolbein Ellifsen (23), Norwegian, assistant and cook

Hugh Evans (23), British, assistant zoologist

Anton Fougner (30), Norwegian, scientific assistant

Nicolai Hanson (28), Norwegian, zoologist

Herlof Klövstad (30), Norwegian, medical officer

Ole Must (22), Laplander, dog handler

Persen Savio (22) Laplander, dog handler

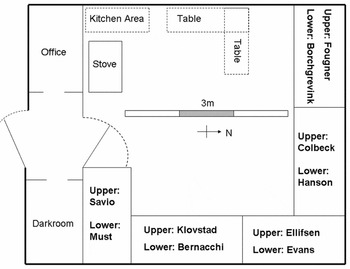

The British Antarctic Expedition was led by Norwegian Carsten Borchgrevink (34), and sailed in Southern Cross. Landing at what became known as Ridley Beach, the team constructed a prefabricated hut, the ‘only example left on any continent of humans’ first dwellings’ (Anon. undated: 9). Fig. 1 shows the arrangement of the hut, and the initial bunk allocations. These bunks, 1.9m long by 0.9m wide, run in two levels along three of the walls, with the stove and the (now lost) communal table taking up the remaining space (Harrowfield Reference Harrowfield2004). It would have been impossible for all ten men to stand in the central space at one time without unintentionally coming into physical contact. As an illustration of how tight this space is, a maximum of four contemporary visitors are permitted inside the hut at one time (Management Plan for Antarctic Specially Protected Area (Anon. 2010: 159).

Fig. 1. Plan of the hut at Cape Adare and initial bunk allocations.

Such visitors are not permitted to lie down in the bunks: but doing so would allow them to stare up at the wooden ceiling of the hut, or to look on the underside of the boards of the bunk above, just as the original residents would have done each night for more than a year. Any rule-breaking visitor would be rewarded with a view of graffiti, notes, bon mots and drawings, written into the woodwork by pencil.

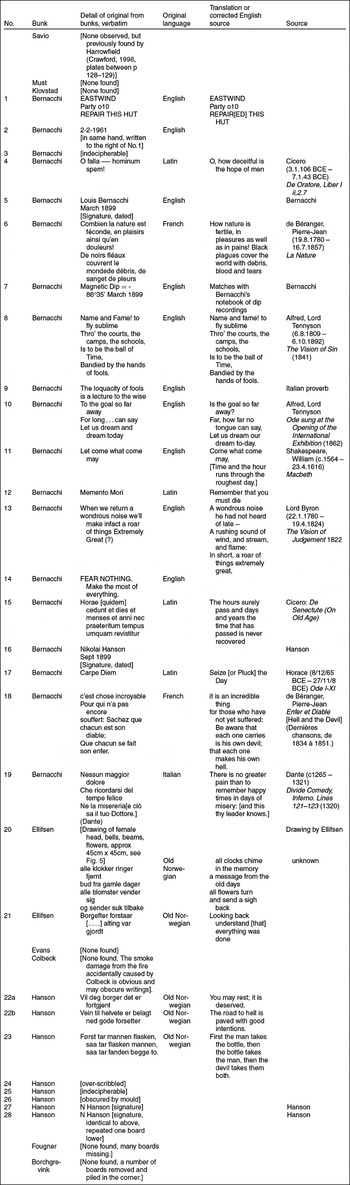

Figs. 2 – 6 show the wood over the bunks of the most prolific writers, Louis Bernacchi, Kolbein Ellifsen and Nicolai Hanson. Each phrase of graffiti is numbered in the figures, and Table 1 displays the detail of each phrase, a translation, and the source. With two exceptions, handwriting above each bunk has been matched by comparison with extant holograph manuscripts (listed below under References) to the owner of the bunk as detailed in Fig. 1. The exceptions are Nos. 1 and 2, written by an unknown US service man, and No. 16, Hanson's signature.

Fig. 2. ‘Eastwind’ markings under Bernacchi's bunk.

Fig. 3. Quotes 3–17, under Bernacchi's bunk.

Fig. 4. Quotes 18–19, under Bernacchi's bunk.

Fig. 5. The remarkable picture by Kolbein Ellifsen.

Fig. 6. Quotes 22–28, under Hanson's bunk.

Table 1. Graffiti Catalogue – working bunk by bunk from south to north, numbers refer to each phrase of graffiti in figures two to six.

These inscriptions, written in the only private place each man enjoyed, provide a glimpse into the minds and moods of the first occupants, who were ‘all packed together in this dirty hut – unable to go out’ as yet another storm swept the bare headland (Crawford Reference Crawford1998: 174). For these men, their bunks became a precious personal space, the wood above their heads became a canvas for drawing and a place for notes that could not be sequestered by their insecure leader.

Such a situation, in which diaries and notes were required to be handed over, was a very real possibility. On 3 February 1899, Bernacchi records in his diary that Borchgrevink openly asserted that, according to contract he could take the diaries of the expedition members (Crawford Reference Crawford1998). Borchgrevink had successfully raised the funds for the expedition by selling the exclusive news and publication rights to Sir George Newnes. In an attempt to prevent leaks, the leader had also banned expedition members from writing letters home, to be taken from Cape Adare by Southern Cross (he later relented). Leaders often reproduce or project forward the way in which they themselves have been led. Hugh Evans, assistant zoologist on the expedition, wrote ‘Sir George Newnes, by the way, showed a lot of interest in his investment, but little interest in Borchgrevink’ (Evans Reference Evans1974: 23). Even before their arrival on the continent, Borchgrevink's discordant leadership style was emerging. The friction and ‘oppressiveness’ (Bernacchi, diary 25 December 1899 in Crawford Reference Crawford1998: 171) that this style of management created are a thread running through the bunk scribblings, which were an important confidential outlet for some of the men.

Not all of the men wrote in their bunks, for example no writings were found in the bunk occupied by Evans, who noted ‘[we] kept ourselves occupied and did not suffer from winter depressions of the Belgica’ (Evans Reference Evans1974: 25). Despite being as young as Bernacchi (both were 22 at the start of the expedition) Evans’ character seems more robust and stoic, although he did share Bernacchi's low opinion of their leader. (It is worth noting that de Gerlache's Belgica was released from her over-wintering in the sea-ice of Antarctica on 14 March 1899, just as Southern Cross team were settling into their new hut at Cape Adare. Thus Borchgrevink's team could not learn from de Gerlache's experiences).

Analysis of selected inscriptions

The pencil writings can be categorised into one of three themes: firstly that most ancient, irresistible and enduring form of graffiti, a statement that ‘I was here’; secondly the leaving behind of a message for future visitors and finally an expression of misery at the situation (with occasional exhortations to help overcome the despair).

‘I was here’ is first seen at Nos. 1 and 2, in the only writings found not to have come from the 1899–1900 expedition. 12 men from the US Coastguard ship Eastwind, a component of Operation Deep Freeze ’61, landed at Ridley Beach on Cape Adare on 3 February 1961, to collect ornithologist Brian Reid and Dr Colin Bailey who had been studying the Adélie penguins. The coastguard team carried out basic repairs to the hut in order to prevent it from re-filling with snow, which had been cleared by Reid and Bailey during their stay, and could not help but to leave their mark (Capelotti Reference Capelotti1994).

No. 5, Bernacchi's signature, dated March 1899, is one of the earliest writings under the bunks, for it was on 1 March 1899 that the flag was raised at Cape Adare, the buildings were completed and Southern Cross sailed north (Borchgrevink, 1900).

It may seem odd that Nicolai Hanson's signature, No.16, should appear in Bernacchi's bunk. Hanson had become ill and at some point in September 1899 (none of the diaries give a specific date) Bernacchi volunteered his less draughty bunk to him, in order to make the bed-ridden Hanson more comfortable (Baughman Reference Baughman1999). Hanson died there on 14 October 1899, of beri-beri (Guly Reference Guly2012) and became the first known burial on the continent.

Nicolai Hanson had married, aged 28, just before the expedition set off. Having previously worked for the British Museum as a specimen collector and taxidermist, he become the expedition's zoologist and was held in high regard by the other members. Evans described him as ‘a fine man’ (Evans Reference Evans1974: 28) and Borchgrevink noted that he was ‘generally up to a practical joke’ and like the best jokers, Hanson smiled when he inevitably became the butt of jokes in return (Borchgrevink Reference Borchgrevink1901: 75).

The most elaborate ‘I was here’ message comes in the form of Kolbein Ellifsen's sketch, No. 22. Ellifsen's unpublished, neatly written-up memoire contains many similar sketches, some of which have been cut from other pages (possibly a rough copy expedition diary) and stuck into the notebook (Ellifsen Reference Ellifsen1900). The sketch on the ceiling of the hut has a breadth of approximately 45cm, and is made of numerous images including a female head, flowers, architectural details and a bell. Ellifsen has clearly taken his time, the intricacy of the piece suggests it was drawn over nine or ten separate sessions. As such it is incoherent: any intended message is lost. Ellifsen escaped an office based working life in Norway to join the expedition as the cook; he was 23 years old at the time. Like Hanson, he also had no previous Antarctic experience.

Messages to future visitors are the second category of graffiti found. Although similar in handwriting, it is possible that No. 22a found in Hanson's bunk was not in fact written by him. The sentiment of the lines makes it much more likely that a team member (may be Bernacchi, a temporary bunk resident) reflecting on Hanson's death, is sending his respected and hard working friend a message ‘You may rest; it is deserved.’

In Ellifsen's bunk, a hard-to-find line reads ‘Looking back understand [that] everything was done’ (No. 21). Could it be that he was seeking to assure us that Hanson's death was not as a result of neglect? Bernacchi's diary for 20 October concurs, ‘[Dr Herlof Klövstad] was indefatigable in his attention to the end, but alas all to no avail’ (Crawford Reference Crawford1998: 153).

Many of Bernacchi's quotation choices, when read with the benefit of hindsight, could appear to be messages to future visitors. However, Bernacchi's writings throughout his journal (and later book) are rooted in the present, therefore his scribblings should be read in the context of the third category, outpourings at the depressing situation he found himself in.

We should review the causes and consequences of the feelings of pitifulness experienced, in particular, by Bernacchi, during the winter at Cape Adare. Bernacchi, educated in the classics (as is amply demonstrated by his selection of quotations) and dedicated to his work as expedition physicist, was disgusted with Borchgrevink's slovenly attitude towards science and what Bernacchi describes as his vulgarity. In addition, Borchgrevink's vacillating, fickle leadership style compounded Bernacchi's feeling that the winter was an ‘incarceration’ (Crawford Reference Crawford1998: 164). For a summary of this difficult situation see Baughman Reference Baughman1999: 90–104.

Whilst Borchgrevink had the skill, charisma and tenacity to create, finance and outfit the expedition, which even attracted the praise of Clements Markham (although the source for this is Borchgrevink's own book of 1900!), it is clear that he did not have the complementary but distinct skill of leadership in the field. It is leadership that has the greatest effect on the mood of a party in these over-winterings, far more so than environmental factors of darkness, isolation or cramped quarters. The following description, from a study of psychological factors amongst male-only groups in the Antarctic, could have been written as a description of Borchgrevink's character: ‘Individuals with high needs for novelty and new sensations, whose thoughts and actions are routinely unconventional, who are emotionally unstable, or who are unconcerned with social approval seem unsuited for work in such environments’ (Biersner and Hogan Reference Biersner and Hogan1984: 495).

However, it must be remembered that this was the first ever over-wintering on the Antarctic continent. The significance of Borchgrevink's achievement, including his pioneering use of primus stoves, kayaks, and sledge-dogs, was overshadowed on his return by a combination of the lingering ill feelings amongst the expedition members, Scott's Discovery expedition and Borchgrevink's own thoroughly dull narrative of the expedition (1900). Combined with the many column inches devoted to the second Boer War, 1899–1902, the result was that this expedition was not afforded the recognition that it really deserved. In 1930 Borchgrevink was eventually rewarded with the Royal Geographical Society's Patron's Medal, with the citation admitting that ‘justice had not been done at the time to the pioneer work of the ‘Southern Cross’ expedition’ (Hinks (editor) Reference Hinks1930).

Louis Bernacchi's reaction to Borchgrevink's management of the expedition, as seen through the graffiti, is influenced by his clearly superior intellect, his young age (only 22), and his thoroughly international upbringing. With an Italian family heritage, Bernacchi was born in Belgium to parents who had lived in England. When he was aged 7 the family moved to Australia, where for bedtime reading his father selected French classics (Crawford Reference Crawford1998). His inscriptions under the bunks range from classical poets to obscure French political commentators, but all with one common theme, that of bemoaning the leadership of the expedition.

Tennyson makes his first of many Antarctic appearances at No.8. A favourite of later explorers such as Scott and Shackleton, the poet even has a rocky point on Ross Island named for him by the members of the Southern Cross expedition. Bernacchi would demonstrate his extensive knowledge of the poet later during the Discovery expedition. He won a debating competition against Ernest Shackleton, by just one vote, to decide who was the greater poet: Tennyson or Robert Browning (Mayer Reference Mayer2014).

Bernacchi may have held back from writing the last line of the quotation from Dante's Divine Comedy (No.19). He scribbles ‘There is no greater pain than to remember happy times in days of misery’ but leaves out the next line ‘and this thy leader knows.’ The subject of Dante was the cause of a quarrel between Borchgrevink and Bernacchi, as noted in the latter's diary on 25 April 1899. Could it be that he wrote on the boards at the same time?

Most damning of all ‘The loquacity of fools is a lecture to the wise’ (No.9). There is no doubting who Bernacchi believed to be the foolish and the wise, describing in his diary how he felt that in Borchgrevink's case ‘sublime ignorance and personal conceit are such factors it is indeed folly to seek intelligence’ (Crawford Reference Crawford1998: 100).

Hanson suggests one of the causes of Borchgrevink's deficiencies, with a traditional verse (No. 23) ‘First the man takes the bottle, then the bottle takes the man, then the devil takes them both.’ Janet Crawford, Bernacchi's niece and editor of his diaries, suggests in her commentary that other members of the expedition were ‘figurines to be moulded to one man's dream’ (Crawford Reference Crawford1998: 90). Borchgrevink's dream of fame and fortune as a result of the expedition was yet to be realised: through that winter, he was biding time before seeking a triumphant return home to claim the laurels, hence his lassitude and a propensity to drink. He was to ‘Drink to heavy ignorance’ as exhorted by the poet from a line in Tennyson's The vision of sin, part of which is also quoted by Bernacchi (No.8).

Conclusion

For as much as Louis Bernacchi, William Colbeck and Nicolai Hanson came to dislike their leader, it must be remembered that Borchgrevink did ‘not present any experiences of his own which might go to lighten the difficulties of Antarctic research’ (Strachey (editor) Spectator, 28 September 1895: 13) for he had only one brief expedition on which to draw any experience, that of a sealing trip with Henrik Johan Bull. Bull (like Newnes) was a poor role model of leadership, honestly describing his own expedition as ‘a series of burlesque performances’ (Bull Reference Bull1984: 90).

If Borchgrevink's leadership was poor, at least his planning was thorough. He ‘made careful preparation’ (Baughman Reference Baughman1999: 81) and had not only thought about the requirements for portable stoves, the benefits of sledge dogs and so on, but he had perceived the importance of exclusive bunk space. ‘The bunks were closed [by a sliding panel] after the plan followed by the sailors on board whaling vessels. . .and, like this, it is private. . .It was by a special recommendation from the doctor that I made this arrangement’ (Borchgrevink Reference Borchgrevink1901: 91).

He was ahead of his time here too, for only later was ‘a perceived need [recognised] among all [over-wintering] crew members to create their own personal space in a confined setting’ (Palinkas Reference Palinkas2003: 13). In commissioning these semi-private spaces, Borchgrevink had provided a canvas on which the expedition members could sketch out their discontent.

These inscriptions represent sincere emotions at the time of writing during their winter confinement, but such feelings would fade in the memories of the explorers once they returned to civilisation's many distractions. For all Bernacchi's seeming misery, and despite pleading ‘may I never pass another twelve months in similar conditions and surroundings’ (Bernacchi 1900) he did return south with Scott on the Discovery (as did Colbeck on Morning), the draw of Antarctica eventually proving stronger than the memory of the discomfort. ‘How nature is fertile, in pleasures as well as in pains!’ (No.6).

Further work

I am bound to have missed some writings. In particular, images appear in That first Antarctic winter, (Crawford Reference Crawford1998), of doodles from within the bunk of Salvo, which I did not find on my visit. Harrowfield reports a cartoon in Salvo's bunk which I also missed (D. Harrowfield, personal communication 3 March 2015). Harrowfield carried out the first systematic inventory of the hut during the 1981–1982 season, when he also noted writings by Colbeck. Crawford mentions lines in William Colbeck's bunk that seem to refer to the loss of Hanson, ‘Money can buy things, good and evil, but all the wealth in the world cannot buy you a friend, nor pay for the loss of one’ Crawford Reference Crawford1998: 225).

The collecting of images used for this paper was possible under the terms of a tourist visit to the hut, including adhering to the ‘no touch’ rule. A follow-up visit (with appropriate permissions in place) should examine the boards that have been removed from the bunks and stacked in the north west corner, the loft (used by Borchgrevink as a bolt hole), office and darkroom spaces.

Financial support

None

Conflicts of interest

None