Introduction

Aroma in rice is an important trait that determines the market price of rice (Giraud, Reference Giraud2013). There are hundreds of volatile compounds causing fragrance of rice. Among them 2-acetyl-1-pyrroline (2AP) is regarded as the major aromatic compound which contributes to the fragrance in Basmati type rice (Sood and Siddiq, Reference Sood and Siddiq1978; Buttery et al., Reference Buttery, Ling and Juliano1982; Buttery et al., Reference Buttery, Ling, Juliano and Turnbaugh1983). From linkage mapping studies Pinson. (Reference Pinson1994); Lorieux et al. (Reference Lorieux, Petrov, Huang, Guiderdoni and Ghesquiere1996); Cordeiro et al. (Reference Cordeiro, Christopher, Henry and Reinke2002) and Bradbury et al. (Reference Bradbury, Fitzgerald, Henry, Jin and Waters2005a) determined that the major gene responsible for fragrance through elevated levels of 2AP is located on chromosome 8. Bradbury et al. (Reference Bradbury, Henry, Jin, Reinke and Waters2005b) reported that the presence of an eight base pair deletion and three single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in exon 7 of the betaine aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 (badh2) gene on Chromosome 8 produces non-functional variant of the BADH2 enzyme leading to the accumulation of 2AP in Basmati type rice. The particular allele containing the eight base pair deletion and three SNPs in exon 7 was named as badh2.1 by Kovach et al. (Reference Kovach, Calingacion, Fitzgerald and McCouch2009) and as badh2-E7 by Bindusree et al. (Reference Bindusree, Natarajan, Kalva and Madasamy2017).

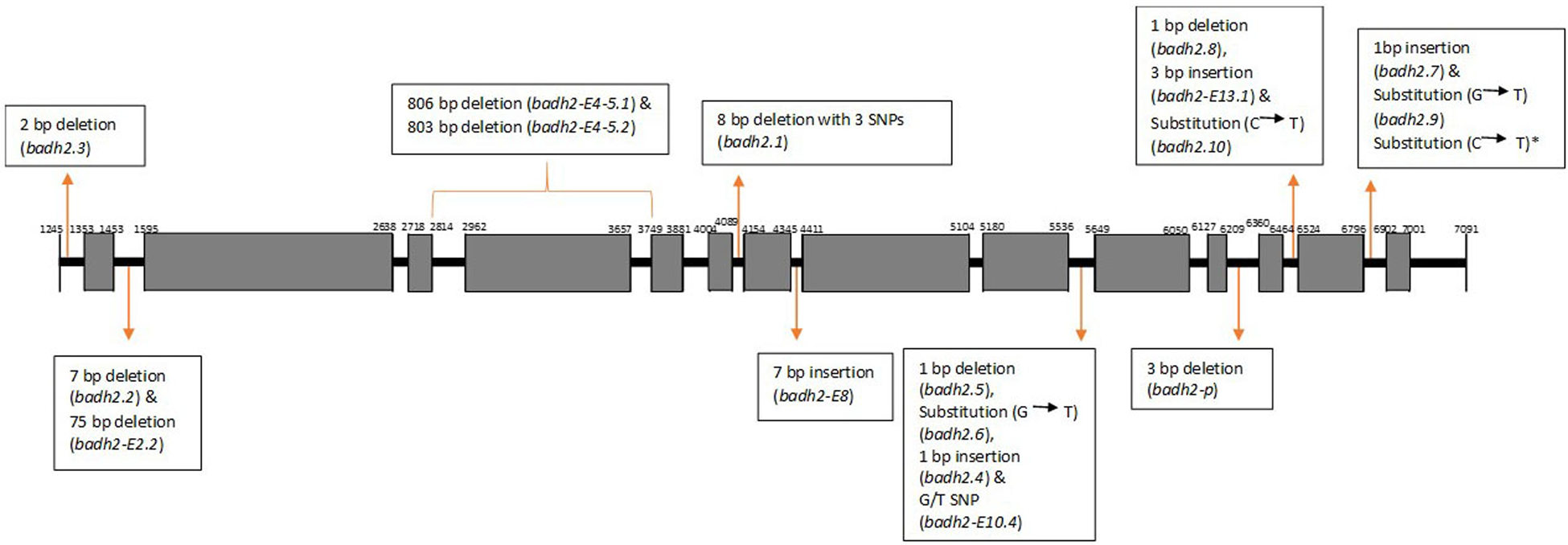

The complete badh2 gene comprising 15 exons and 14 introns encodes 503 amino acids (Kovach et al., Reference Kovach, Calingacion, Fitzgerald and McCouch2009). Kovach et al. (Reference Kovach, Calingacion, Fitzgerald and McCouch2009) have reported that 10 possible allele types (badh2.1 to badh2.10 containing different mutations in exons) that contribute to fragrance in rice (Table 1). In addition, the presence of other several mutations have been reported (Shao et al., Reference Shao, Tang, Tang, Luo, Jiao and Wu2011; Shao et al., Reference Shao, Tang, Chen, Wei, He and Luo2013 and He and Park, Reference He and Park2015) in fragrant rice varieties from different geographical areas (Table 1).

Table 1. Details of the mutations in exons regions of badh2 gene analysed in this study

a Name has not been given for the allele.

Chen et al. (Reference Chen, Yang, Shi, Ji, He, Zhang and Xu2008) and Sakthivel et al. (Reference Sakthivel, Sundaram, Rani, Balachandran and Neeraja2009) have predicted that biosynthesis of 2AP occurs via a polyamine pathway with the involvement of the wildtype BADH2 enzyme. If the BADH2 enzyme is functional gamma-aminobutyric acid is produced giving phenotypes without fragrance, conversely if the BADH2 enzyme is non-functional, the pathway diverts to the production of 2AP. Supporting evidence reported by Hinge et al. (Reference Hinge V, Patil and Nadaf2016) demonstrated that reduced expression of the badh2 gene dose increases 2AP accumulation in rice grains. The badh2.1 allele encodes a truncated non-functional BADH2 protein with 251 amino acids due to a premature stop codon.

Bradbury et al. (Reference Bradbury, Henry, Jin, Reinke and Waters2005b) developed a marker known as frg comprising four primers (ESP, IFAP, INSP and EAP) to differentiate the badh2.1 using multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Dissanayaka et al. (Reference Dissanayaka, Kottearachchi, Weerasena and Peiris2014) developed a cleaved amplified polymorphic sequence (CAPS) marker known as Bad2.7CAPS, to differentiate the badh2.7 allele that possesses ‘G’ insertion in exon 14. There is a need for employing user-friendly DNA markers to detect different functional mutations of badh2 gene to accelerate rice breeding. In this study, we attempted to detect potential fragrance causing mutations, and the respective varieties carrying them, through in-silico analysis using badh2 sequences available at Rice SNP-Seek-Database of International Rice Research Institute (Alexandrov et al., Reference Alexandrov, Tai, Wang, Mansueto, Palis, Fuentes and Mauleon2014). As only a few breeding efforts have been reported on the utilization of badh2.7 allele, we validated the Bad2.7CAPS marker as a functional marker using several traditional varieties and breeding lines.

Materials and methods

Extraction of badh2 sequences from rice SNP-seek database

Sequences of badh2 in rice from Asian countries were obtained from the Rice SNP-Seek Database developed by IRRI (http://snp-seek.irri.org) using the locus number Os08g0424500 located on chromosome 8 (20,379,823–20,385,975 bp). A total of 1878 rice accessions representing 22 countries of Asia were analysed: one from Afghanistan, 170 from Bangladesh, 19 from Butan, 51 from Cambodia, 253 from China, 378 from India, 226 from Indonesia, two from Iran, 34 from Japan, 120 from Laos, 64 from Malaysia, 67 from Myanmar, 42 from Nepal, one from North Korea, 32 from Pakistan, 146 from Philippines, 29 from South Korea, 47 from Sri Lanka, 26 from Taiwan, 134 from Thailand, one from Tibet and 35 from Vietnam.

Mutation identification, multiple sequence alignment and amino acid sequence analysis

All previously reported mutations in badh2 exon sequences (Table 1 and Fig. 1) leading to non-functional BADH2 enzyme were considered in the analysis. Using MEGA 7 sequence analysis software (Kumar et al., Reference Kumar, Stecher and Tamura2016) the sequence of each rice accession was aligned with the complete cDNA of Oryza sativa indica non-fragrant variety Nanjing11 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/eu770319.1). For each accession with a variant mutant sequence the whole predicted coding sequence of badh2 was translated into an amino acid sequence using the ExPASy-Translate tool (https://web.expasy.org/translate/) to check any predicted functional change in amino acid sequence compared to the wild type amino acid sequence translated from GenBank Acc. No. EU770319.1.

Fig. 1. Schematic diagram showing the exon regions of badh2 gene (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/eu770319.1) and their previously reported mutations as indicated in Table 1.

Plant materials used for screening of fragrant alleles

Seven aromatic varieties, two non-aromatic varieties and 19 advanced breeding lines derived from two rice crosses, Iginimitiya × Bg 300 and Suwandel × Bg 360 were obtained from Rice Research and Development Institute (RRDI), Batalagoda, Sri Lanka (Table 3). Phenotyping for fragrance in the advanced lines had been done previously by a sensory evaluation method as reported by Sood and Siddiq (Reference Sood and Siddiq1978). This material was used to examine the applicability of DNA markers for badh2.1 and badh2.7 for detecting fragrance allele types.

Identification of fragrant alleles by DNA markers

Genomic DNA was extracted from 2- week-old rice seedlings using 3 cm long leaf samples according to the method described by Gimhani et al. (Reference Gimhani, Kottearachchi and Samarasinghe2014). The leaf samples were homogenized with 300 μl of DNA extraction buffer (1 M KCl, 1 M Tris HCl, 0.5 M EDTA) and the homogenized samples were incubated at 70°C for 20 min. They were centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 15 min at room temperature and the supernatant retained. DNA was precipitated by adding 100 μl of ice cold iso-propanol to the supernatant followed by incubation at 4°C for 15–30 min. The DNA was pelleted by centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 15 min at room temperature. DNA pellets were washed with 150 μl of 70% ice cold ethanol by centrifuging at 13,000 rpm for 10 min. The supernatants were removed and the air dried pellets dissolved in 200 μl of 1/10 TE buffer (10 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA) were used for the PCR.

For badh2.1 (fgr) genotyping, the PCR was conducted using four primers, namely, ESP (TTGTTTGGAGCTTGCTGATG), IFAP (CATAGGAGCAGCTGAAATATATACC), INSP (CTGGTAAAAAGATTATGGCTTCA) and EAP (AGTGCTTTACAAAGTCCCGC) by multiplexing in a single tube using the method of Bradbury et al. (Reference Bradbury, Henry, Jin, Reinke and Waters2005b). Online Supplementary Fig. S1(a) shows the primer annealing locations and amplification profile expected from badh2.1 and wildtype alleles. For Bad2.7CAPS genotyping, the PCR was performed in a total reaction volume of 15 μl, consisting of 5 × PCR buffer, 2.5 mM dNTPs, 25 mM MgCl2, 0.2 μM Bad2.7 primer (Bad2.7CAPS-Forward: 5′-CAAGTGAAGGGGATTG-3′ and Bad2.7CAPS-Reverse: 5′-CCAAAGGCATGATGTCAGGTCG-3′), 5 u (1 μl) Taq DNA polymerase and 20 ng of genomic DNA. Thermal cycle parameters included the following: an initial denaturation at 95°C for 1 min, 35 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 56.9°C for 30 s and 72°C for 1 min, followed by a final extension at 72°C for 7 min.

The amplified PCR products were digested by BslI restriction enzyme (BioLabs, China), which is a thermostable type II restriction endonuclease with interrupted recognition sequence CCNNNNN/NNGG (/, cleavage position) (Hsieh et al., Reference Hsieh, Xiao, Oloane and Xu2000). The digestion reaction was carried out with 10 μl of PCR product in 16 μl of nuclease free water, 2 μl of 10× buffer and 2 μl of 10 U/μl BslI enzyme at 55°C for 16 h, and the DNA was visualized in 3.0% agarose gel. Online Supplementary Fig. S1(b) shows the primer annealing locations and amplification profile expected from badh2.7 and wildtype alleles.

Results

Prevalence of mutated alleles in exon regions of badh2 gene in Asian rice germplasm

This study searched for sequence variants in exons of the badh2 gene across 1878 accessions (online Supplementary Table S1) in Rice SNP-Seek Database and identified 75 accessions with the predicted loss of function mutations. The badh2.1 allele was the most prevalent mutant allele occurring in 63 accessions while the badh2.7 allele was the second most prevalent allele occurring in nine accessions (Table 2 and Fig. 2). In addition three novel non-functional alleles were observed in one accession each (Table 2).

Fig. 2. Multiple sequence alignment showing badh2 variants for accessions originating from Sri Lanka and India in the rice SNP seek database. (a) Accessions with a G insertion in the 14th exon indicated by * (badh2.7). (b) Accessions with three SNPs and an 8 bp deletion in the 7th exon (badh2.1).

Table 2. Rice accessions detected with mutations in badh2 gene

a Several substitutions in exon 1, 2, 4, 5 and 10.

b Several substitutions in exon 5 and 10.

c T deletion in exon 9.

Chung Yi (IRGC Acc. No. 1427-1) had several sequence mutations including G/C, C/G, T/A and C/G substitutions in exon 1, a C/T substitution in exon 2, A/G, A/T, T/A, T/G, T/G substitutions in exon 4, A/G, A/G, C/T substitutions in exon 5 and C/T, C/A, A/T, A/G, G/T, A/G, G/A, C/A substitutions in exon 10. The cDNA nucleotide sequence for this accession is predicted to generate a truncated 333 amino acid sequence resulting in an incomplete BADH2 protein. Chugoku 68 Hen (IRGC Acc. No.72514-1), a Japanese rice accession contained mutations such as A/W, C/Y, C/Y, A/R, A/R substitutions in exon 5 and C/Y, C/M, A/W, A/R, G/K, A/R, G/R substitutions in exon 10 (R = G or A substitution, Y = T or C substitution, K = G or T substitution, M = A or C substitution, S = G or C substitution, W = A or T substitution). It is predicted to produce a truncated 306 amino acid sequence instead of full length 503 amino acids. The accession, E Pluak (IRGC Acc. No. 64297-1) of Thailand origin had a T deletion in the 9th exon that is predicted to induce premature stop codon giving rise to a BADH2 protein with only 359 amino acids.

Twenty-seven accessions contained synonymous mutations in badh2 exons that were not predicted to cause loss of function of the wild type allele (online Supplementary Table S1). Several substitutions were observed in exon regions such as substitution of C/T in exon 02, C/T in exon 05, A/C in exon 06, A/T in exon 07, G/A and C/A in exon 10, C/T in exon 12, G/A in exon 13, G/A in exon 14 and C/T in exon 14 in nine countries analysed in this study (online Supplementary Table S1). These synonymous silent mutations were not considered of value to breeders.

The badh2.1 allele was present in accessions from Bangladesh, Cambodia, India, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, Nepal, Pakistan, Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam while badh2.7 allele was present only in accessions from India, Bangladesh, Pakistan and Sri Lanka. There are 47 accessions with Sri Lankan origin in the rice SNP-Seek Database, out of which only Kurulu Wee (IRGC Acc. No. 66615-1) can be considered as a fragrant rice variety due to the presence of the badh2.7 allele. Accessions from countries such as Afghanistan, Butan, Iran, North Korea, South Korea, Taiwan and Tibet did not contain any fragrant rice accession that possessed the mutations reported in Table 1.

Variations of intron regions of the badh2 gene

A number of substitutions and Indels were detected in the intron regions of the badh2 fragrance gene in the rice accessions analysed in comparison with GenBank Acc. No. EU770319.1 (data not shown). These are considered to have no effect on the expression of BADH2. We noted at least one mutation in at least one intron in each of 600 accessions tested in this study, however they were unlikely to affect the splicing process as they were present at the middle of the introns.

Identification of germplasm with badh2.1 allele

This study used 28 rice lines (Table 3) including traditional varieties, improved varieties and advance breeding lines to compare fragrance phenotype with genotype using previously reported fragrance allele specific markers.

Table 3. Types of badh2 alleles detected using allele specific markers

*Aromatic lines.

a Advance breeding progeny lines of Iginimitiya × Bg 300.

b Advance breeding progeny lines of Suwandel × Bg 360.

The badh2.1 frg marker originally developed by Bradbury et al. (Reference Bradbury, Henry, Jin, Reinke and Waters2005b) amplified the 257 bp band for fragrant allele in varieties MA2, At 309 and At 311 containing badh2.1 allele (Table 3; selected varieties shown in Fig. 3(a)). None of Sri Lankan traditional rice contained the badh2.1 allele although it is the most predominant allele in the South Asian region. The varieties, MA2, At 309 and At 311 are improved varieties which had been selected from crosses with a Basmati variety which could be the donor of badh2.1 allele. As expected, non-fragrant rice varieties, Bg 300 and Bg 360 produced wild type alleles for the locus. Hence, the badh2.1 (frg) marker comprising ESP, IFAP, INSP and EAP primers is reliable for discrimination of badh2.1 from its wild type, however it clearly is not a definitive test for the fragrant phenotype in all rice.

Fig. 3. Molecular marker profiles for differentiation of fragrant alleles. (a) badh2.1 allele using marker developed by Bradbury et al. (Reference Bradbury, Fitzgerald, Henry, Jin and Waters2005b); (b) badh2.7 allele using Bad2.7CAPS marker; lane 1: Iginimitiya (aromatic); lane 2: Suwandel (aromatic); lane 3: Suwanda samba (aromatic); lane 4: Suduru samba (aromatic); lane 5: Bg 300 (non-aromatic); lane 6: At 311 (aromatic); lane 7: At 309 (aromatic); lane L: 100 bp ladder.

Validation of Bad2.7CAPS marker with fragrant rice germplasm

Dissanayaka et al. (Reference Dissanayaka, Kottearachchi, Weerasena and Peiris2014) developed a CAPS marker that could discriminate badh2.7 allele from its wild type. This is a two-step marker, requiring amplification of the target 457 bp DNA fragment followed by restriction digestion. The digest run on an agarose gel shows two possible patterns depending on the allele present (Fig. 3(b)). Rice accessions that did not have G insertion in 14th exon region (wild type) produced three bands (255, 67 and 121 bp) due to the presence of two BslI restriction sites. Rice accessions which had the badh2.7 allele produced only two visible bands (188 and 255 bp) due to the presence of the G insertion that disrupted the BslI restriction site (in the wild type sequence, the BslI restriction site was present in the 188 bp fragment so it was split into two, 67 and 121 bp). Therefore, rice Inginimitiya, Suwandel and Suwanda samba varieties possessing the fragrant badh2.7 allele exhibited two DNA bands due to nucleotide G insertion that disrupted the BslI site (Fig. 3(b)). Advanced breeding lines of the Suwandel × Bg 360 cross did not show either the mutant badh2.7 allele or the fragrance phenotype while advanced lines of the Iginimitiya × Bg 300 cross exhibited both the fragrance phenotype and the mutant badh2.7 genotype (Table 3) indicating the applicability of the Bad2.7CAPS marker for the selection of fragrant trait in these segregating populations. However, traditional rice variety, Suduru samba did not exhibit either badh2.1 or badh2.7 fragrant alleles in spite of its pleasant fragrance.

Discussion

The present study revealed that 72 rice accessions conserved at the International Rice Germplasm Collection contain either the common badh2.1 allele or the rare badh2.7 allele (Table 2). Kovach et al. (Reference Kovach, Calingacion, Fitzgerald and McCouch2009) and Dissanayaka et al. (Reference Dissanayaka, Kottearachchi, Weerasena and Peiris2014) have shown that badh2.1 and badh2.7 mutant alleles critically affect the three dimensional structure of the BADH2 protein. Therefore, it is likely that aroma in aromatic rice varieties containing badh2.1 and badh2.7 is due to enhanced 2AP levels due to a non-functional BADH2 enzyme. Kovach et al. (Reference Kovach, Calingacion, Fitzgerald and McCouch2009) showed that, rice accessions possessing these two alleles produce 2AP, the major aroma causing compound. Therefore, the 72 accessions revealed in this study could be used in combination with the markers for badh2.1 and badh2.7 as parents in fragrant rice breeding.

Moreover, this study revealed a SNP mutation, T deletion in 09th exon, in the Thai rice variety, E Pluak (IRGC Acc. No. 64297-1), which has not been reported previously and therefore, it can be speculated that E Pluak could be a novel potential fragrant rice variety. Two other novel mutation types were detected in the Chinese variety Chung Yi (IRGC No. 1427-1) and in the Japanese variety Chugoku 68 Hen (IRGC Acc. No. 72514-1). Further studies on sequence verification and phenotype assessment are necessary to confirm these three novel mutation types and the relationship between these alleles and fragrance.

Based on the variants detected in diverse genotypes it can be speculated that the badh2.7 allele is limited only to rice varieties originating in the South Asian region while the badh2.1 allele is found among varieties originating from countries of both Southeast Asia and South Asia. Although the badh2.1 was the most prevalent allele in accessions of Asian origin, none of the 47 Sri Lankan varieties possessed this mutation. This may be due to the fact that those varieties originated at the most southern part of Asia, where gene flow based transfer of badh2.1 might not have occurred. The four countries (Pakistan, India, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka) containing rice germplasm with badh2.7 allele are geographically close to each other, suggesting that one possible route for gene flow for the badh2.7 allele was from a common ancestor that evolved in this region. Our results also support the theory that the badh2.1 allele could have originated in the japonica varietal group while badh2.7 could have originated within the indica varietal group as hypothesized by Kovach et al. (Reference Kovach, Calingacion, Fitzgerald and McCouch2009), due to the geographic distribution pattern of the alleles among countries of origin.

Mutations in intron regions such as a TT deletion in intron 2 and a repeated AT insert in intron 4 have been reported by Chen et al. (Reference Chen, Yang, Shi, Ji, He, Zhang and Xu2008) in Local Chinese fragrant rice varieties. However, whether the particular mutations in introns affected on fragrance was not reported. Mukherjee et al. (Reference Mukherjee, Saha, Acharya, Mukherjee, Chakrabort and Ghosh2018) have observed a high rate of accumulation of SNPs in introns as compared to exons in Arabidopsis thaliana. Moreover, they found a strong negative correlation between total exonic SNP density and intron number indicating that introns may protect the exonic regions against the harmful effects from such mutations. There are few reports illustrating the impact of mutations in intron regions in plants because usually introns do not contribute to protein structure, unless affecting the splicing process. Therefore, further studies are necessary to observe the impact of the variations in intron regions observed in this study on fragrance.

Breeding of fragrant rice consumes much time and needs skilled labour for the evaluation of fragrance. This task can be achieved more easily if a DNA marker that is tightly linked with fragrance is used in marker assisted breeding (MAB) programs. There are many reports of successful use of fragrant allele specific markers in MAB (Shi et al., Reference Shi, Yang, Chen and Xu2008; Hashemi et al., Reference Hashemi, Rafii, Ismail, Mohamed, Rahim, Latif and Aslani2015; He and Park, Reference He and Park2015 and Peng et al., Reference Peng, Zuo, Hao, Peng, Kong, Peng, Nassirou, He, Sun, Liu, Pang, Chen, Li, Zhou, Duan, Song, Song and Yuan2018). We tested local germplasm to detect the badh2.1 fragrant allele using the frg (Bradbury et al., Reference Bradbury, Henry, Jin, Reinke and Waters2005b) DNA marker. The results confirm that this badh2.1 marker is practically convenient to discriminate badh2.1 from its wild type, but that they are not suitable for discrimination of other variants for aroma.

In Sri Lanka, At405, At306, At309, At311 and At373 are improved high yielding fragrant varieties which inherited the pedigree of Basmati or IR 70422-66-5-2 (IRRI variety), both of which contain the badh2.1 fragrant allele. More recently, the Rice Research and Development Institute, Sri Lanka focused on breeding programs with local traditional varieties, targeting pleasant fragrance and adaptability characters which could be obtained from Suwandel and Inginimiiya. However, due to the lack of the availability of DNA markers, Suwandel and Inginimiiya could not be employed with expected rapidity via MAB programs. In the present study we employed the Bad2.7CAPS marker to detect the badh2.7 variant in unexploited traditional aromatic varieties in order to inform the potential in MAB. Three traditional rice germplasm conserved at the genebank of RRDI, Sri Lanka (Iginimitiya, Suwandel and Suwanda samba) were found to have badh2.7 allele at 14th exon (Fig. 3 and Table 3) and screening was continued with progression of MAB. Also, it was observed that traditional rice variety, Suduru samba exhibited neither badh2.1 nor badh2.7 alleles so its fragrance may be due the presence of another unknown allele in its genome – either in badh2 or another gene.

In breeding programs of rice, molecular markers are the preferred method to select for the fragrant trait at the early growth stage to reduce the time and cost of breeding. Although, there are reports of successful developments of aromatic rice by MAB using badh2.1 markers (Shi et al., Reference Shi, Yang, Chen and Xu2008 and Hashemi et al., Reference Hashemi, Rafii, Ismail, Mohamed, Rahim, Latif and Aslani2015), no such breeding efforts have been reported for badh2.7 based DNA markers. As badh2.7 is the second most prevalent allele in the Asian region, this marker has potential to be used in the discovery of unutilized fragrant varieties and accelerate breeding if varieties carrying the allele are used as parents.

The majority of rice consumers prefer fragrant rice over non fragrant if other traits are matched. However, only a few fragrant rice varieties such as the Basmati varieties and Thai Jasmine varieties have become highly popularized and therefore, they are sold at a premium price in the market. If there are more varietal choices for fragrant rice, then farmers and breeders will gain the opportunity to cross them with other suitable parents to develop new fragrant varieties which could ultimately lead to the supply of more fragrant rice varieties at a competitive price. For sustainable rice production, it is necessary to breed varieties that are best suited to the environment of a particular country because when popular varieties such as Basmati are introduced to other regions they can be reported to have poorer growth and yield compared to their maximum yield in their native countries, Pakistan and India. Therefore, novel fragrant germplasm identified using the methods described in this study is likely to have as yet untapped value for breeding or cultivation by rice consuming countries.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study revealed 75 fragrant accessions out of 1878 rice accessions originating from different Asian countries, available at International Rice Germplasm Collection, IRRI. The most prevalent fragrant allele in Asia was badh2.1, present in 63 accessions, while the second most prevalent allele was badh2.7, present in nine accessions. Three accessions that possessed new allelic variations with the potential of causing fragrance have also been found, including one of which had a T deletion in the 9th exon. There is now potential for the development of molecular markers for these novel variants. The presence of nucleotide variants at least in one intron of the badh2 gene was a common feature of all tested accessions. The screening systems of badh2.1 and badh2.7 alleles were validated using Sri Lankan germplasm. The marker, Bad2.7CAPS was confirmed to be capable of discriminating fragrant and non-fragrant phenotypes using traditional and advanced breeding lines of rice.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1479262120000015.

Acknowledgement

The authors acknowledge NRC-09-11 and NRC-16-016 research grants funded by the National Research Council, Sri Lanka.