Introduction

High diversity of crop landraces in farmers' fields reflects their long-term interactions with changing environmental conditions as well as socio-economic and cultural factors that influence farmers' priorities and preferences (Tripp and van der Heide, Reference Tripp and van der Heide1996). Landraces (which loosely include local varieties, traditional varieties and farmers' varieties) constitute a very important part of the world's biocultural heritage (van de Wouw et al., Reference van de Wouw, Kik, van Hintum, van Treuren and Visser2009). Owing to their broad genetic diversity, these landraces can thrive in heterogeneous ecological niches, in increasingly parched and barren fields and despite erratic weather patterns – conditions which typify traditional and subsistence-oriented farming systems. Moreover, these genetically diverse landraces play a significant role in crop improvement programmes while serving as an effective hedge against future challenges to agricultural production.

In a study which spanned 33 years, Ford-Lloyd et al. (Reference Ford-Lloyd, Brar, Khush, Jackson and Virk2008) confirmed the link between the number of rice landraces (RLs) and genetic diversity. Clear association was discovered for the number of RLs extant in farmers' fields and genetic diversity richness, thereby providing a simple proxy indicator for genetic diversity losses. Unfortunately, numerous studies have reported about the dwindling numbers of crop landraces and their wild relatives due to the ingress of modernization, among other factors. A few years back, a group of conservationists retraced Vavilov's iconic journey in the Pamir Highlands of Tajikistan, the Ethiopian Highlands and the Colorado Plateau of Southwestern North America more than a century before. This later study revealed the extinction of numerous crop species previously documented by Vavilov due to ‘significant climatic, environmental and human-caused changes’ which had severely impacted local agriculture in these areas (Hummer, Reference Hummer2015). Known as genetic erosion, these concomitant losses of crop landraces and their wild relatives had been widely reported in the scientific literature (Gao, Reference Gao2003). Recognizing the seriousness and urgency of conserving plant genetic diversity, the convention of biological diversity (CBD) advocated for the reduction of genetic diversity losses by 70% (UNEP, 2010). Furthermore, Frankel (Reference Frankel1974) concurred that ‘urgent action is needed to collect and preserve irreplaceable genetic resources’.

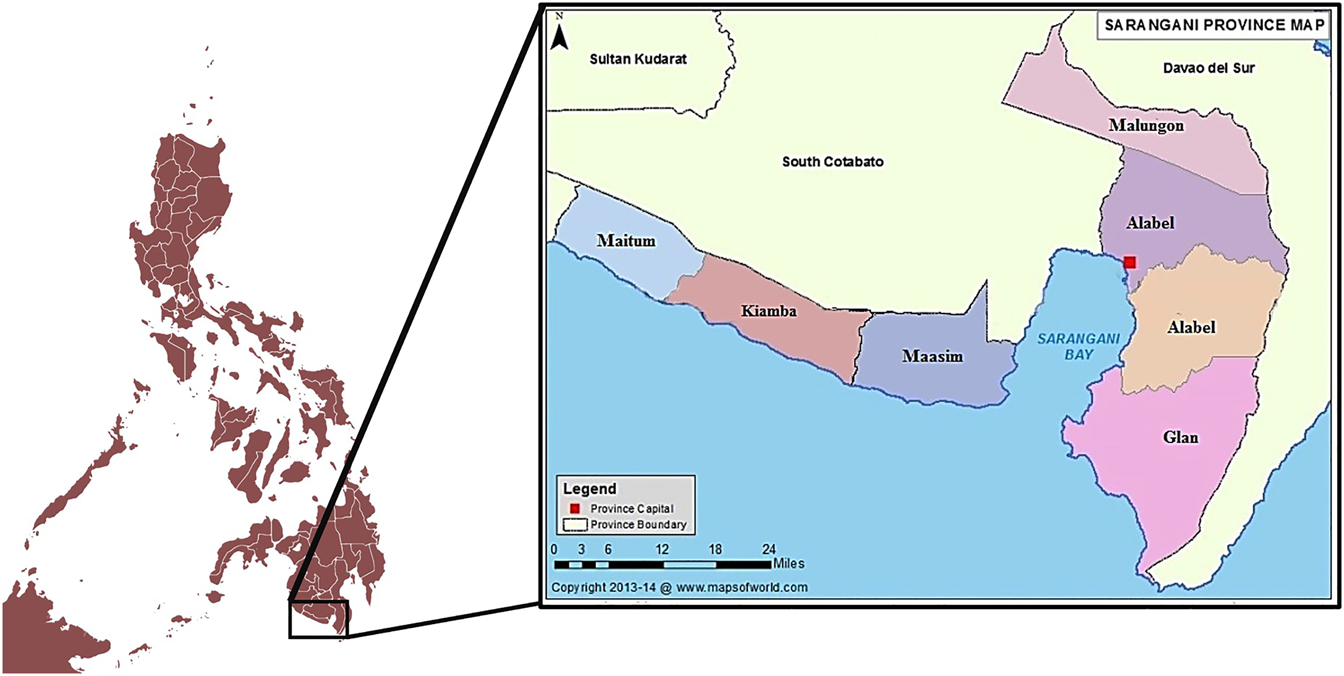

Sarangani, a province located in Southern Philippines, consists of seven municipalities, viz. Malapatan, Alabel, Maitum, Glan, Kiamba, Malungon and Maasim (Fig. 1). In these areas, upland rice is cultivated under rain-fed conditions, at the subsistence level and in the absence of agro-chemical inputs. Zapico et al. (Reference Zapico, Aguilar, Abistano, Carino-Turner and Jacinto-Reyes2015) were able to record high varietal diversity for upland farms after a province-wide inventory. Unfortunately, these premium RLs are gradually diminishing in numbers due to present-day scenarios in these areas. This current study was therefore undertaken to (1) inventory RLs extant in Sarangani upland farms, (2) detect the occurrence of genetic erosion in farmers' fields and (3) identify major driving forces and consequences for this agricultural phenomenon.

Fig. 1. Location Map of Sarangani Province and its seven municipalities. Source: www.mapsoftheworld.com (Accessed on 28 Dec 2019).

Methodology

The study was carried out from in 14 upland sitios (villages) in Sarangani Province in Southern Philippines (viz. Datal Bukay, Small Margus and New Aklan in Glan, sitio Mutu Ladal, Nomoh in Maasim, Kihan and Kinam in Malapatan, sitios Ihan, Cabnis, Glamang in Datal Anggas, Alabel, sitio Lamlifew in Datal Tampal and Malabod in Malungon, sitio Lampong in Upo and Angko in Batian, Maitum and Malayo in Kiamba (Fig. 1).

This current study, which is cross-sectional in nature, utilized the emic (insider's view) approach. Rapid rural appraisal (RRA) techniques (i.e. focus group discussions (FGD), key informant interviews (KIIs), individual surveys using a semi-structured questionnaire, community immersion and field observation) were carried out in the different study sites. The questionnaire was translated into the tribal dialect using a local intermediary for respondents who could only speak their language. Twenty participants consisting of male and female farmers across a wide age spectrum, sitio officials and tribal elders were chosen for the activity. Only farmers who were cultivating rice during the time of the study, who had 10 or more years of farming experience and who gave explicit consent were considered for KII and questionnaire administration. Pertinent information about traditional rice, such as varietal diversity and losses, ethnobotanical information and major pressures to the upland rice resource base were elicited using a participatory approach. Since no information was available, occurrences of past climatic anomalies and natural catastrophes were based on historical references by farmers during FGD and KII. Obtained information was subsequently corroborated by consultations with the local government of Sarangani. Farm profiling and field observations were also undertaken to lend credence to farmers' perceptions and knowledge obtained during FGD.

Results

Farmer profile

Of the 47 Sarangani farmers interviewed, 78.7% were male, 98% were married and had approximately 25.9 years in farming. Having a mean age of 46.9 years, over half (53.1%) of the farmer respondents belonged to the 39–69 years age bracket while 9% elderly farmers had ages ranging from 70 to 80 years. More than half of the farmers (53.5%) had Blaan ancestry with Tboli (30.2%), Kaolo (9.3%), Visayan, Manobo and Kalagan comprising the rest. In terms of education, 46% had primary education, 24% had several years of secondary education and 28% never had formal education at all. Almost all farmers (95.4%) revealed that they derived household income solely from on-farm activities while the remaining few had small retail stores as additional revenue sources. When asked about access to credit, 92% replied in the negative while a small number of farmers revealed that they were able to avail of seed loans. Furthermore, majority (69.8%) of the farmer respondents divulged that they did not have training of any kind while the rest underwent trainings/seminars which were conducted by local agricultural offices and other line agencies.

The Sarangani rice resource base

A total of 80 RLs and two modern varieties (MVs) were documented in Sarangani upland farms during field visits. As can be gleaned from online Supplementary Table S1, majority of the RLs were owned by Blaan farmers with Tboli farmers coming in second at 43 and 35 varieties, respectively. In 2017, the Philippine Department of Agriculture through its local offices implemented the Special Area for Agricultural Development (SAAD) programme which involved distribution of Kasagpi seeds (a rice variety from nearby Sultan Kudarat town) for increased agricultural production. Two MVs, Banay and Sinandomeng, were also documented to grow alongside traditional rice in Maasim and Alabel farms. These MVs were brought by farmers from the lowlands by mid-2018 to try them out. Furthermore, online Supplementary Table S2 also shows that 27 varieties were early maturing, 38 were late maturing while 12 RLs were culturally important to farmers. Twelve of the RLs were both for consumption and for sale during instances of excess or surplus harvests while 56 varieties were solely for family consumption.

Rice varieties with cultural significance

Sarangani farmers claimed that RLs are an integral part of tribal culture (25%), and their lives (18.8%), ensure food security (18.8%), are necessary for long-term survival of the tribes (12.5%), are a tribal staple (12.5%), are a symbol of the tribe (6.3%) and promote good health (6.3%). Bisol, a glutinous variety, is used in making biko (a dessert made from sticky rice, brown sugar and coconut milk) and rice cakes during Tboli festivities. Owing to its sticky texture, this variety symbolizes unity and staying power of married couples. During weddings, Bisol is cooked with chicken and eaten by the couple so that they will have a ‘sticky’ married life and stay together in spite of problems. Tang, another glutinous variety, is also used as a symbol of unity in Tboli marriage ceremonies.

Kanlen or Rice Ancestor, a Blaan variety, means ‘a cut above the rest’ among Sarangani rice varieties. Farmers believe that as the ancestor of all varieties, its origins go all the way back during olden times. Kanlen should be planted first during the planting season so that there will be a bumper crop. For Tbolis, the variety Mal-an or Rice President, is considered as the ‘leader of all rice varieties’. According to farmers, Mal-an should not disappear from the farms or bad luck will befall them. Due to severe pest infestation, however, this variety was no longer found in the visited farms. Mlikat Lagfisan, or Rice Soldier, is special to Blaan farmers and is believed to be endowed with mystical powers. This variety is planted along rice field borders to protect the crop against pestilence. It is also given to babies as first solid food to make them smarter. Like Mal-an, however, Mlikat Lagfisan was not observed in farmers' fields during the study period.

For Kaolo farmers, consumption of variety Amihan (or Rice Medicine) helps in warding off bad luck or death in the family. This variety purportedly helps reconcile conflicting families. Moreover, the variety Tulon is cherished by Tboli farmers due to its pleasant aroma, taste and its valuable use for indigenous pest control. When the crop is ready to harvest, farmers excise the first two panicles and leave them for pests so that the entire crop will be spared from infestation. Upon harvesting, a handful of Tulon seeds is roasted with pandan (Pandanus odoratissimus L.), pounded, mixed with a few metal shavings and cooked. Farmers believe that pandan makes the entire rice harvest aromatic while metal shavings improve quality by making seeds hard, solid, with entire margins and not easily broken (timgas) thereby minimizing the presence of broken grains.

Uyayang, Luwaro and Satiman are likewise considered as special rice by Tboli farmers who serve them to visitors during special occasions. The name of the third variety means ‘one of a kind’ in the Tboli dialect. Sugen, which means beehive, is called as such because of its remarkably large panicles and high yielding potentials. Abtu Kulang, widely known to exhibit high volume expansion, ‘rises when cooked’ and can cause a clay pot to shatter. Farmers further disclosed that Bulawan is very aromatic and should not be given to persons suffering from stomach-related disorders. When ingested, Bulawan makes acid balance in the stomach go awry, causing severe discomfort to a person.

Upland rice genetic erosion: in retrospect

During the 1950s to the 1960s, all areas in the Sarangani uplands had thick forest cover and small populations composed of Lumads. Upland rice farming and the traditional slash and burn (kaingin) started during 1961–1970 in all sites except for New Aklan, Glan and Banlas, Malapatan where these started a decade earlier. During the 1970s to the 1980s, migrants started coming to these areas to establish homes, thereby intensifying upland rice farming along with kaingin activities. Consequently, wide expanses of forests were cleared and trees were cut to build homes and other community structures. The influx of migrants and bustling community activities continued until 1990s up to the early 2000s. Peace and order problems were mostly experienced by early settlers of Malapatan and Alabel who revealed that Muslim atrocities during 1961–1970 caused severe community unrest. Furthermore, sporadic attacks from communist rebels (New People's Army (NPA)) resulted in community displacement in Datal Anggas, Alabel and Kihan, Malapatan from 1981 to 1990. To date, occasional NPA attacks have been still reported in these two areas.

Synergistic effects of extractive human activities and climate change resulted in wide scale environmental degradation in the Sarangani uplands. Earliest incidences of landslides, flood and drought were reported in Banlas, Kihan and New Aklan, Glan. In 2001–2010, the communities of Kinam, Malapatan and Glamang, Alabel experienced more frequent typhoons while New Aklan had monthly landslide events during this period. As for pests, earliest reports of agricultural devastation due to rats and army worms came from Banlas, Kihan, Sitio Angko, Maitum and Lamlifew, Malungon in 1981–1990. Farmers from Kinam and Glamang likewise revealed that rats and army worms come at regular intervals of 3–4 years after 2015. Also emerging recently as a major rice pest is Leptocorisa spp., which attacks rice during the milking stage, causing widespread crop damage.

Also found in the Sarangani uplands is Sige-sige corn which was introduced sometime in 2014, cotton, pineapple and hybrid corn which were introduced in Lamlifew and Malungon from 1981 up to the early 2000s and abaca that was brought to Glamang and Alabel sometime between 2000 and 2010. MVs were also brought to Sitio Angko, Glamang and New Aklan during the early 2000s while Muto Ladal and Maasim reported of cultivating MVs during the early quarter of 2018. Moreover, the introduction of SAAD rice varieties for intensified upland rice production also started in 2017 with farmer beneficiaries reportedly from Kinam and Kihan in Malapatan, Sitio Angko in Maitum and New Aklan in Glan.

All these events that transpired in the study areas, have directly or indirectly contributed to the genetic erosion of traditional rice varieties. Significant reductions of RLs were observed by farmers in New Aklan, Glan as early as 1991–2000 while the rest of the farmers reported that RLs disappeared en masse from 2001–2010 (for Lamlifew and Glamang) and 2011 up to the present time in Banlas, Kinam, Sitio, Angko and Muto Ladal.

Genetic erosion: current pressures

Rice varietal losses: farmers' perspectives

Farmers in Sarangani Province select specific RLs for conservation and planting on the bases of the following preferred traits enumerated according to decreasing levels of importance: seed quality, palatability, aroma, drought resistance, early maturity, hardiness and yield. As can be noticed, yield was not a prime consideration for these farmers who planted rice mainly for household consumption. On the other hand, the 40 RLs shown in online Supplementary Table S2 were discarded by farmers due to myriad reasons. Among these were: late maturity, labour intensiveness, lodging with torrential rains/strong winds, tallness, very long awns, very small grains and because the panicle is almost completely enclosed by leaves (Gunting) making threshing difficult. Some farmers also discarded the varieties Manumbay and Kawayan since the former had a distinct preference for cooler areas close to forests while the latter competed with Sige-sige corn and was deemed inferior to MVs. In contrast, 14 varieties were irreversibly lost due to severe pest infestation (i.e. rats, birds, locust and Leptocorisa spp.). Climate-related disasters (extreme heat and prolonged drought) also caused widespread devastation in Sarangani upland farms, resulting in varietal losses. Occasionally, farmers are forced to consume their seed stocks when rains do not come on time and when their food supplies run out. An elderly farmer from Glan likewise recalled discarding Albaal in 1947 due to its extremely long awns while most landraces were lost during the late 1990s to the early 2000s. The loss of the variety Mal-an, in particular, was recalled by Tboli farmers with a twinge of regret since this variety was culturally important.

Weakening seed supply systems

In the Sarangani farms, seeds are planted, harvested and a portion (made of best quality seeds) is set aside for the next planting season. The rest of the harvest, which is allocated for home consumption, is placed inside a tiral (hollowed out bamboo receptacle) and stored in the fol (traditional rice granary). To regenerate rice seeds stored in the tiral, farmers simultaneously sow several rice varieties in individual plots in the same field or in succession if the land is quite small. Unfortunately, current socio-ecological scenarios have effected changes to the age-old seed supply systems of the Sarangani tribes.

A significant number (64%) of interviewed farmers revealed that seed stocks are presently insufficient for the needs of the community. When seed allocations are lost, they obtain planting materials from exchanges within the community, with other communities, from relatives and friends, between farmer purchase and from government agencies or non-government organizations. Only 42% of the farmer respondents claimed that they are seed secure while the rest revealed that they occasionally obtain planting materials from off-farm sources out of necessity. Furthermore, 95% of farmer respondents revealed that they save left-over seeds for the next planting season using traditional storage methods (Zapico et al., Reference Zapico, Aguilar, Abistano, Carino-Turner and Jacinto-Reyes2015). When asked if they experienced seed losses during storage, 72% of respondents disclosed that they lost stored seed due to rats and improper drying. Some farmers also revealed that their families consumed seeds intended for planting during prolonged dry seasons while some stated that their seed stores were stolen by unknown individuals.

Socio-economic, ecological and institutional pressures

Visits to different upland communities revealed a similar trend – RLs that had been maintained by farmers for many decades are dwindling in numbers because of various external pressures. The introduction and eventual proliferation of alternative cash crops such as recycled Roundup Ready corn (Sige-sige corn) profoundly impacted rice genetic diversity by displacing traditional RLs in Sarangani upland fields. In sitio Lamlifew, Malungon specifically, fields which were previously planted with RLs now have cotton and pineapple maintained in a plantation setting. So too with the tribal community in Malayo, Kiamba which abandoned upland rice farming for commercial abaca production. In this area, no more traditional rice varieties were reported by locals who instead purchased rice from nearest lowland markets.

Sarangani upland communities regularly experience natural calamities, the compounded effects of which tribal communities are still reeling from. Potentially destructive by themselves, these calamities have been observed by Sarangani locals to be increasing in frequency and intensity during recent years. Among these natural calamities are El Nino or prolonged drought (longest recorded was 7 months), typhoons, extremely high temperatures, landslides and flash floods. In Barangays Upo and Batian in Maitum, a very long drought spell in 2016 almost crippled agricultural production. Farmers also divulged that several times in the past, their entire crop was carried downhill by flash floods. Flood waters, rushing from the mountains, dump huge volumes of soil and debris in low-lying areas. In Malapatan, a sitio (village) had to be physically transferred to another location with farmers leaving behind their homes and standing crops in the aftermath of a severe flash flood event. Extreme heat was also reported to have caused scorching of rice plants resulting in crop failure.

Furthermore, farmers disclosed that natural calamities wreak considerable damage to the environment, the extent of which is totally exacerbated by extractive human activities and climate change. In Muto Ladal, Maasim, forest cover was very sparse due to unabated kaingin activities. Consequently, water was scarce and fewer rice varieties were observed when compared to past few years. Extensive deforestation was also observed in Kiamba due to commercial production of abaca, Sige-sige corn and coffee. Moreover, well-intentioned government programmes (i.e. SAAD programme) aimed at ensuring rice sufficiency in the marginal Sarangani uplands also resulted in diminished rice genetic diversity in the uplands. Externally sourced out rice seeds were purchased in bulk and distributed along with livestock such as carabaos, ducks and goats. Unfortunately, this meant intensified kaingin in remaining forests of Maitum and Kiamba. During field work, forest clearing was observed to be proceeding at an alarming rate in these areas.

Still in Maitum, the past 4 years proved to be debilitating for upland agricultural production. Rats, expected by farmers every 3–4 years, were reported to have caused widespread hunger and rice varietal losses during the middle of 2016. Except for the traditional variety, Uyayang, all RLs maintained by farmers in Maitum disappeared during this time due to the devastating effects of pest infestation (birds, army worms, rats and locusts) and long drought. Likewise, in many areas of the province, pests made easy pickings of rice plants heavy with ripened grains. Young children, once paid to drive birds away, had gone to school so Sarangani farmers had to take upon themselves this task in order to save their harvests. Farmers also lamented that mole crickets and Leptocorisa oratorius have recently emerged as major pests specifically in Malapatan and Maitum. Mole crickets (Gryllotalpa orientalis Burmeister), which were reported by Sarangani farmers of late, mostly feed on subterranean/basal parts of the rice plant (such as tillers and roots) causing it to collapse.

Moreover, while the communist insurgency problem had been effectively curbed in many areas in Sarangani due to military presence, it has persisted in Malapatan and Alabel where rebels have managed to establish a stronghold. In Banlas, Malapatan and Datal Anggas, Alabel specifically, sporadic outbreaks of hostility are being reported even up to now. This protracted armed struggle traces its origins to the decades long rebellion of the NPA against the Philippine government. Consequently, the farmers' regular work routines become disrupted and in certain cases, they abandon their communities as well as standing crops in order to evacuate.

Discussion

Cultural traditions: positive and negative impacts on rice genetic diversity

In the Sarangani upland farms, the continued practice of cultural traditions has had an enhancing effect on rice genetic diversity. Diverse utilization of RLs especially in tribal ceremonies (i.e. weddings, healing and thanksgiving), the continued observance of traditional farming rituals, seed keeping by women farmers and the annual observation of harvest festivals promoted the continued cultivation of RLs in the upland farms. Seed exchanges among farmers to replenish depleted seed stocks also enriched the Sarangani rice resource base. That the RLs are passed on by farmers to the next generation ensures that these priceless genetic treasures are conserved for posterity. On the other hand, several pressures which drastically reduced rice genetic diversity in the Sarangani uplands were identified and classified according to the following categories.

Categories of genetic erosion drivers

Data generated across multiple RRA techniques revealed a broad intersection of ecological, cultural, socio-economic and institutional drivers affecting the traditional upland rice resource base of Sarangani. Presented hereunder are the identified drivers contributing to rice varietal losses in the Sarangani uplands.

Ecological

During the early days of Sarangani Province, forest cover was thick and tribal population in the uplands consisted of a few households. Owing to the availability of vast tracts of land on which to plant crops, slash and burn farming was sustainable (and even beneficial) because it allowed for regrowth of ageing forests. Subsistence farmers cleared a small forest patch, planted rice for a few seasons, left it to fallow for a few years and came back to the farm after the soil had sufficiently ‘rested’. With increased migration, extensive environmental devastation and the gradual shift to a cash-based economy, however, slash and burn farming (kaingin) has emerged as one of the foremost causes of farmland degradation in Sarangani Province. While essentially cultural to tribal farmers, unregulated kaingin caused the shrinking of watershed areas and consequently water scarcity in the upland farms. The subsequent harvesting of remaining saplings for commercial charcoal production transformed once verdant forests into unproductive grasslands dominated by cogon (Imperata cylindrica). Additionally, the traditional farming practice of planting rice along steep hillsides with no soil control measures also exacerbated soil-related problems. In the Sarangani upland farms, resulting farmland degradation severely constrained agricultural production, causing rice varietal losses on an unprecedented scale since the early part of the 2000s.

Extreme climatic events, which are inextricably linked with natural disasters, also wrought irreversible rice varietal losses in Sarangani Province. Morin et al. (Reference Morin, Calibo, Garcia-Belen, Pham and Palis2002) reported that a long drought episode in the wake of the 1997 El Nino and the subsequent flooding after two successive super typhoons in Northeastern Philippines in 1998 resulted in massive losses of rice diversity. Poudel et al. (Reference Poudel, Sthapit and Shrestha2015) reported that a heavy hailstorm devastated Nepalese farms resulting in seed deficiencies during the next 2 years. Recurring pest epidemics also led to decimation of entire rice fields in the Sarangani uplands during the past few years. As a consequence of the destruction of their habitats, hordes of rats descended to the upland farms, eating everything in sight. In a study in three Philippine provinces, Litsinger et al. (Reference Litsinger, Canapi, Bandong, Lumaban, Raymundo and Barrion2009) reported the prevalence of soil and seed pests in dryland rice ecosystems. Likewise, Kumar et al. (Reference Kumar, Pradeep, Sridhara and Manjunatha2012) and Arora and Dhaliwal (Reference Arora and Dhaliwal1996) ascribed extensive rice field devastation to recurrent insect pest attacks in India.

Cultural

Cultural changes in the upland communities also contributed significantly to genetic erosion in Sarangani farms. The shift from the traditional sahul (volunteerism) farming type to paid labour made farming a very costly endeavour for the farmers, discouraging many from planting rice. During the time of the study, the daily wage in the upland farms was Php150 (or $3) for both men and women farmers. While quite a pittance when compared to lowland salary rates, this amount was considered exorbitant by Sarangani upland farmers. Similar findings about the whittling of the genetic base of crop landraces due to shifting farmer priorities were put forward by van de Wouw et al. (Reference van de Wouw, Kik, van Hintum, van Treuren and Visser2009) and Aguilar (Reference Aguilar2018).

Weak seed supply systems are also factors to reckon with in rice genetic erosion. Incidentally, the informal seed supply system in the Sarangani uplands is vulnerable to the damaging effects of natural calamities, extreme climatic events, pest infestation, the shift to Sige-Sige corn and outmigration. Rice seeds, when not planted every few years, also lose viability resulting in varietal losses. When the inherent instability of the Sarangani seed supply system becomes heightened by these negative pressures, losses of rice genetic diversity become a foreseeable outcome. Similar studies in the Philippines and Africa by Morin et al. (Reference Morin, Calibo, Garcia-Belen, Pham and Palis2002), Shrestha (Reference Shrestha, Pratap and Sthapit1998) and Erskine and Muehlbauer (Reference Erskine, Muehlbauer, Jackson, Ford-Lloyd and Parry1990), respectively affirmed that weak seed supply systems can have adverse consequences on crop genetic diversity.

Socio-economic

In the Sarangani uplands, farmers' decision to choose cash crops (Sige-sige corn, modern rice varieties, coffee and abaca) over traditional rice and the mindset change among the tribal youth also resulted in the reduction of rice genetic diversity in these areas. With the wholesale shift to cash crops, RLs became unavailable for tribal households who either shifted to the consumption of corn, sweet potato or lowland rice. Furthermore, many tribal youth moved to the lowlands to acquire education, non-farming jobs or to escape the drudgery and tediousness associated with upland rice farming. This tribal diaspora to the lowlands resulted in the abandonment of Sarangani upland farms and in the consequent losses of rice genetic diversity in these areas. Aguilar (Reference Aguilar2018), van de Wouw et al. (Reference van de Wouw, Kik, van Hintum, van Treuren and Visser2009) and Brush (Reference Brush1992) discovered this same propensity of the youth to look for better economic prospects at the expense of their rice farms in their respective studies. Similarly, Hummer (Reference Hummer2015), while ‘following in the footsteps of Vavilov’, also came up with the same findings.

Institutional

Government policies and extension programmes may also directly or indirectly affect rice genetic diversity negatively by altering farmers' decision-making processes. The government's SAAD programme, which promoted wide scale planting of 1–2 varieties (obtained from outside sources) instead of local RLs resulted in significant genetic losses. Furthermore, easy access to chemical inputs (esp. herbicides) convinced rice farmers to shift to Sige-sige corn since it obviated the need for manual weeding which they considered as tedious. Since the past five years, Sige-sige corn has become a conspicuous feature of the Sarangani uplands, with upland rice being cultivated by a handful of farmers. In Maasim, Glan and Malungon, upland rice farms were nowhere to be seen except in the remotest villages. In a study in Northeastern Philippines, Morin et al. (Reference Morin, Calibo, Garcia-Belen, Pham and Palis2002) reported that some policies and programmes instituted by the Department of Agriculture contributed to genetic erosion of local RLs. Moreover, outbreaks of hostilities between government forces and Muslim and communist insurgents in Malapatan and Alabel, also resulted in the evacuation of tribal families who left their homes and rice fields behind. During such skirmishes, farmers either evacuate or hole up in their houses for weeks on end, thereby neglecting their crops and causing massive losses of rice genetic diversity. Vaughan and Chang (Reference Vaughan and Chang1992), van de Wouw et al. (Reference van de Wouw, Kik, van Hintum, van Treuren and Visser2009) and Hammer and Teklu (Reference Hammer and Teklu2008) likewise confirmed that armed conflict disrupts daily activities of traditional communities, among them agricultural production.

Rice traditional knowledge: promise and problems

Intimate knowledge of RLs has enabled Sarangani farmers to survive in such harsh and unforgiving terrains through these years. This resilience to the onslaught of calamities and freak weather events can partly be ascribed to the broad genetic base of Sarangani RLs. For instance, varieties Luwaro, Larangan, Lapinig, Mayaman, Fitam Kwat and Byaan were reported by farmers to thrive well in the fields even under prolonged drought conditions. These claims of drought tolerance were borne out by physiological screening of Byaan, Mayaman, Fitam Kwat and Larangan during the germinative and seedling stages (unpublished). Varieties Katiil, Mlato and Kanadal were likewise reported to survive under laboratory-simulated salinity stress (unpublished). The Maitum variety, Uyayang, was also revealed to thrive well in hardpan soils while Suyod was reported by farmers as being able to thrive under a wide range of conditions. Tabaw, on the other hand, repels birds due to its extremely long awns and allows farmers to bring in ample harvest. These potentially promising RLs which have shown promise against biotic and abiotic stresses were planted by farmers when the need arose. They can therefore be utilized to enhance resilience of local farmers to the devastating effects of climate change and other pressures to this extremely vulnerable agroecosystem.

Furthermore, Sarangani farmers (especially the elderly) are keepers of age-old traditional knowledge relating to rice production. In the rain-fed upland farms of Sarangani, planting season is timed with the onset of the rainy season and starts with slash and burn of a nearby forest patch. Kaingin is widely believed to rid the soil of pests and to make it fertile through the nutrient-rich ash. Sowing of rice seeds by dibbling minimizes soil disturbance and consequently, reduces occurrences of soil erosion in steep areas. Synchronous planting is done by many farmers to disperse pests and minimize infestation. Presently, annual and synchronous rice planting are still widely practiced to avert crop losses due to the lack of rains and pest infestation respectively. In these areas, rice planting is done by default by elderly farmers and those who do not have money to cover labour costs, to purchase Sige-sige corn seeds and chemical inputs. In contrast, some traditional practices had been observed to contribute to existing problems in the Sarangani uplands. The tribal practice of kaingin, although cultural to farmers, worsens problems on environmental degradation, climate change, biodiversity losses and water shortage. Planting rice along steep hillsides with no soil conservation measures also exacerbates soil erosion problems, and consequently rice varietal losses.

Incidentally, TK losses which had been documented in the Sarangani uplands can be ascribed to a farmers' changing preferences, government programmes, ageing population of farmers, outmigration and education of the youth and the integration of hitherto isolated farms to local markets. According to Friis-Hansen and Guarino (Reference Friis-Hansen, Guarino, Guarino, Rao and Reid1995), the entire repertoire of TK which had produced and maintained the present diversity of RLs in farmers' fields actually ‘remain on site and has been rarely recorded’. Moreover, the oral nature of TK transmission makes it prone to loss, a reality that can be considered as damaging as the actual loss of the RLs themselves (Posey, Reference Posey1996; Daoas et al., Reference Daoas, Dela Cruz, Damaso, Paredes and Nahangayan1999).

Rice biocultural erosion: the Sarangani situation and beyond

Overall, these results are reminiscent of the study by Dahl and Nabhan (Reference Dahl and Nabhan1992) in North America which identified the introduction of cash crops, loss of seed saving, death or acculturation of traditional caretakers, change in economic base, land use changes, farmland destruction, herbicide and pesticide impact, environmental contamination, loss of seeds to pests and net reduction in the number of farmers as apparent threats to crop genetic diversity. The introduction of MVs (and Green Revolution), in particular, had been espoused by Mathur (Reference Mathur, Guarino, Ramanatha Rao and Goldberg2011), Morin et al. (Reference Morin, Calibo, Garcia-Belen, Pham and Palis2002), Thrupp (Reference Thrupp1998), Long et al. (Reference Long, Li, Wang, Pei, Pei and Sajise1995), van de Wouw et al. (Reference van de Wouw, Kik, van Hintum, van Treuren and Visser2009), Brush (Reference Brush, Serwinski and Faberová1999), Kjellqvist (Reference Kjellqvist and Frankel1973) and Berg (Reference Berg1996) as the early harbinger of worldwide losses of rice genetic diversity. RLs, which ‘owe their existence to several hundreds or thousands of years of evolution and years or even decades of meticulous selection, crop improvement by farmer ancestors’ (Myers, Reference Myers1994; Hammer, Reference Hammer2004) can be wiped out within just a single generation under very adverse conditions. In Sarangani Province, the planting of MVs constituted more the exception than the norm at this stage. Yet their wide scale adoption can potentially lead to the displacement of RLs in farmers' fields. But again, whether these MVs perform well under upland conditions and without synthetic inputs is a matter of conjecture especially since they were at the vegetative stage when the farms were visited.

Assessing genetic erosion is, however, a controversial undertaking even up to this time. The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO, 1996) drives the point succinctly in its Report on the State of the World's Plant Genetic Resources when it declared that ‘because no one can say exactly how much diversity once existed, no one can say exactly how much has been lost historically’. While present data on crop genetic diversity are available, there are no datasets in the past to compare these with. In agreement with these views, Watson-Jones et al. (Reference Watson-Jones, Maxted and Ford-Lloyd2006) and Keisha et al. (Reference Keisha, Maxted and Ford-Lloyd2008) stated that ‘capturing genetic diversity in situ and assessing genetic diversity losses is difficult due to lack of suitable databases’. Wilson et al. (Reference Wilson, Thomas, Fox, Roy and Kunin2004), Green et al. (Reference Green, Balmford, Crane, Mace, Reynolds and Turner2005) and Donald et al. (Reference Donald, Sanderson, Burfield, Bierman, Gregory and Waliczky2007) envisaged an ideal scenario as having a comprehensive baseline data from the past to compare with present values – a prospect that is highly improbable. To make matters worse, information from the field usually relies on recollections of farmers and some glaring inconsistencies occasionally figure out in their responses. This has invariably caused confusion since vernacular names sometimes vary for obviously similar varieties or conversely, similar tribal names could be given for genetically distinct varieties (Appa Rao et al., Reference Appa Rao, Bounphanousay, Schiller, Alcantara and Jackson2002). Consequently, the absence of written record and inherent unreliability of farmers’ memories conspire against the collection of comprehensive data on past genetic diversity in crops. Ford-Lloyd et al. (Reference Ford-Lloyd, Brar, Khush, Jackson and Virk2008) concluded that the process of assessing genetic diversity and erosion, which is done at a single point in time, has very little scientific basis.

Furthermore, losses of rice varieties in the study sites may not totally mean their extinction since these could be grown elsewhere. Concerted efforts should thus be expended to scour all corners of the Sarangani uplands for remaining RLs in farmers' fields. Collected RLs should then be stored using complementary ex situ and in situ conservation strategies. The most feasible approach is the collection and conservation of as much genetic material as possible in anticipation of future needs. Known as the Principle of Prevention (or the Noah's Ark Principle), this approach underlines the necessity of maintaining a very large collection to insulate against future risks (Hammer and Teklu, Reference Hammer and Teklu2008). A case in point was the genetic transformation of cultivated rice for resistance to grassy stunt virus, the gene for which came from a solitary Oryza nivara accession maintained at International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) (Ling et al., Reference Ling, Aguiero and Lee1970). Finally, it must be emphasized that with genetic erosion, it is not just RLs which are ‘under threat of disappearance but also the TK of selecting, utilizing and conserving these materials that had been accumulated for thousands of years’ (Hammer and Teklu, Reference Hammer and Teklu2008). Studies relating to the epistemological bases of TK and genetic erosion should therefore be undertaken to better understand the current situation unfolding in the Sarangani uplands as a consequence of current socio-cultural and ecological scenarios.

Conclusion

This study unveiled high varietal diversity for upland rice and highlighted its cultural importance to the Sarangani upland peoples. Results of the study, however, revealed erosion of the traditional rice resource base and the stripping of the cultural identity of upland tribes due to identified major pressures. Consequently, these changes have undermined food security, causing hunger and suffering in these marginal areas. Interventions involving multiple disciplines/sectors are thus warranted to avert further biocultural losses in the Sarangani uplands. Among the recommended interventions are: (a) complementary in situ (community-managed genebank and on-farm conservation) and ex situ conservation (off site seed storage) strategies to mitigate further losses of rice varieties. (b) Documentation of indigenous knowledge systems and their incorporation in the curriculum of primary schools in tribal communities for the preservation of tribal culture. (c) Granting of various forms of support (microloans and technical support) and incentivizing of traditional rice farming to motivate upland farmers to remain in the uplands. (d) Rehabilitating the denuded uplands using endemic species, criminalizing slash and burn farming and implementing soil conservation measures for ecological restoration. (e) Regulation of Sige-sige corn planting along steep slopes to address soil erosion problems. (f) Further research about climate-resilient rice varieties to enhance resilience of the upland tribes to problems and perturbations. (g) Improvement of seed management and farmer access to RLs through suitable interventions. (h) Establishment of inter-village marketing cooperatives to preclude exploitation by unscrupulous middlemen. (i) Empowerment of tribal women by underlining their roles in the food production process. (j) Finally, linking upland farms to niche markets and incorporating value-added packaging (i.e. geographic indicators, cultural importance of rice varieties) will make traditional farming a lucrative endeavour and will convince more farmers to plant traditional varieties. This will also induce the younger generation to stay in the fields and choose farming as a future profession, thereby revitalizing agricultural production in the Sarangani uplands.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1479262119000406

Acknowledgements

The authors extend whole-hearted thanks to the Southeast Asian Regional Center for Graduate Study and Research in Agriculture (SEARCA), the Philippine Council for Agriculture, Aquatic, and Natural Resources Research and Development (PCAARRD), the Commission on Higher Education (CHED) and the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) for providing various forms of assistance for this study. Local government, barangay and sitio officials are also gratefully acknowledged as well as the Sarangani upland farmers who provided valuable inputs which contributed significantly to the completion of the study.