Introduction

Ginger (Zingiber officinale Rosc.), originated in the Indo-Malayan region, is now widely distributed across many countries as a spice and medicinal plant (Purseglove et al., Reference Purseglove, Brown, Green and Robbins1981; Burkill, Reference Burkill1996; Park and Pizzuto, Reference Park and Pizzuto2002). Traders took ginger from India to Mediterranean region during the 1st century CE (Current Era). The Arabs introduced ginger to East Africa in the 13th century CE and the Portugese spread it to West Africa and the Pacific islands for commercial cultivation (Ravindran et al., Reference Ravindran, Shiva, Nirmal Babu, Korla, Ravindran, Nirmal Babu, Shiva and Johny2006).

The major ginger growing countries include Australia, Brazil, Bangladesh, Cameroon, China, Costa Rica, Fiji, Ghana, Guatemala, Hawaii, India, Indonesia, Jamaica, Mauritius, Malaysia, Nepal, New Zealand, Nigeria, Philippines, Sierra Leone, Sri Lanka, Taiwan, Thailand, Trinidad and Uganda covering a total area of 387,300 ha with a production of 1,476,900 MT. India is the world's largest producer of ginger at present (Table 1). Export of ginger from India was 7500 MT during 2006–2007. ‘Cochin ginger’, ‘Wayanadan ginger’ (India), ‘Chinese ginger’ (China), ‘Buderim Gold’ (Australia) ‘Jamaican’ (Jamaica) are globally traded products. Ginger in various forms is used as food flavorant, antioxidant and antimicrobial besides as deodorizing agent in food. Chinese, Indian, Tibetan and Arabic systems of medicine recognized the medicinal value of ginger since ancient times (Atman and Marcussen, Reference Atman and Marcussen2001).

Table 1 Area, production and productivity of ginger in the world (2006)

Source: http://faostat.fao.org/site/567/DesktopDefault.aspx?PageID = 567.

This review is intended to provide an overview of the diversity of cultivated ginger, its characterization and utilization.

Antiquity

Ayurveda, the Indian ‘science of life’ of approximately 5000 years of antiquity, documented the medicinal value of ginger in treatises such as Charaka Samhita, Shushrutha Samhita and Ashtangahridaya. In Ayurveda, ginger is known as Mahaoushadhi meaning great medicine. It is Sringavera in Sanskrit, the ancient Indian language, which has given way to the Greek Zingiberi and to the Latin Zingiber (Rosengarten, Reference Rosengarten1969; Purseglove et al., Reference Purseglove, Brown, Green and Robbins1981). Ginger is also mentioned in Koran (76: 15–17) though it does not figure in Bible. Ginger was first documented by van Rheede (Reference van Rheede1692) as inschi (inchi) in ‘Hortus Indicus Malabaricus’ – the first printed account of the plants of Western Coast (Malabar Coast) of India.

Taxonomy

The genus Zingiber belongs to the family Zingiberaceae under the order Zingiberales and the tribe Zingibereae (Holtum, Reference Holtum1950). Zingiberaceae includes three other tribes: Hedychieae, Alpinieae and Globbeae (Petersen, Reference Petersen, Engler and Prant1889; Burtt and Smith, Reference Burtt and Smith1972). The tribe Zingibereae has seven other genera: Boesenbergia, Camptandra, Roscoea, Kaempferia, Amomum, Hedychium and Curcuma (Kress et al., Reference Kress, Prince and Williams2002). Jatoi et al. (Reference Jatoi, Kikuchi, Yi, Naing, Yamanaka, Watanabe and Watanabe2006) using rice microsatellite markers assessed the genetic variability among three genera of the family Zingiberaceae: Zingiber, Alpinia and Curcuma and found the origin of the genera diverse covering eight Asian countries. Zingiber contains 150 species and four sections distributed throughout tropical Asia, China, Japan and tropical Australia besides the subspecies (varieties): Z. officinale var. rubra and Z. officinale var. rubrum (Muda et al., Reference Muda, Halijah and Norzulaani2004). Z. officinale is included in the section II, Lampuzium (Baker, Reference Baker and Hooker1882; Sabu, Reference Sabu2003; Larsen and Larsen, Reference Larsen and Larsen2006).

Diversity

Species level

The genus Zingiber includes many economically important species besides Z. officinale as given in Table 2. The Indian species reported include Z. chrysanthum Rosc., Z. rubens Roxb., Z. roseum Rosc., Z. nimmonii Dalz., Z. wightianum Thw., Z. barbatum Wall., Z. squarrosum Roxb., Z. ligulatum Roxb., Z. cernuum Dalz., Z. panduratum Roxb., Z. pardocheilum Wall., Z. intermedium Baker, Z. officinale Rosc., Z. griffithii Baker, Z. gracile Jack., Z. zerumbet Smith, Z. cylindricum Moon, Z. macrostachyum Dalz., Z. spectabile Griff., Z. casumunar Roxb., Z. parishii Hook., Z. clarkii King, Z. capitatum Roxb., Z. marginatum Roxb. (Baker, Reference Baker and Hooker1882).

Table 2 Some of the economically important Zingiber species

Most of the Zingiber species are diploid (2n = 22) except Z. mioga (2n = 55) and set seed. In cultivated ginger (Z. officinale) 2n = 24 and 22+2B are also reported besides the normal diploid number of 2n = 22 (Ravindran et al., Reference Ravindran, Nirmal Babu, Shiva, Ravindran and Nirmal Babu2005). The species is sterile.

Cultivar level

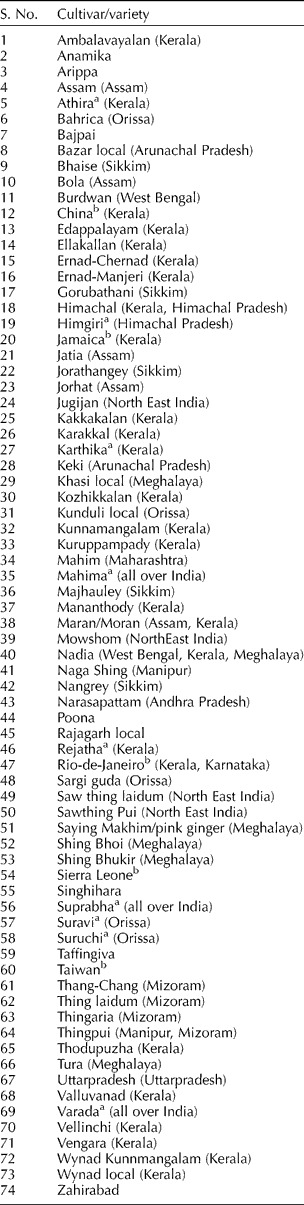

Ginger is a rhizome propagated crop. Cultivar diversity abounds in India and China, which represents the centre of origin of this species, unlike Simmonds (Reference Simmonds1979) observed in many other crops. Geographical spread of ginger clones coupled with mutation and selection are considered to be responsible for the cultivar diversity (Ravindran et al., Reference Ravindran, Sasikumar, George, Ratnambal, Nirmal Babu, Zachariah and Nair1994). About 74 cultivars, most of them with vernacular names, possessing varying levels of quality attributes and yield occur in India (Table 3; Sasikumar et al., Reference Sasikumar, Saji, Ravindran, Peter, Sasikumar, Krishnamurthy, Rema, Ravindren and Peter1999). Major Chinese cultivars include ‘Gandzhou’, ‘Shandong’, ‘Zaoyang’, ‘Zungi big ginger’, ‘Chenggu yellow’, ‘Kintoki’, ‘Sanshu’ and ‘Oshoga’ are three major ginger cultivars from Japan (Ravindran et al., Reference Ravindran, Nirmal Babu, Shiva, Ravindran and Nirmal Babu2005). Ridley (Reference Ridley1912) has reported three types of ginger from Malaysia viz. ‘halyia betle’, ‘halyia udang’, ‘halyia bara’, ‘Native’ and ‘Hawaiin’ are cultivars from the Philippines. Nepal has about 50 cultivars (Sasikumar et al., Reference Sasikumar, Saji, Ravindran, Peter, Sasikumar, Krishnamurthy, Rema, Ravindren and Peter1999). Ginger varieties of Guyana, mainly from the hinterlands of that country, are bold or very bold and lack any varietal names. An obsolete cultivar characterized by very dwarf stature and extremely slender, fibrous rhizome is also grown in Guyana (Sasikumar, Reference Sasikumar2008). ‘Sidda’ and ‘China’ are the cultivars of Sri Lanka (Macloed and Pieris, Reference Macloed and Pieris1984) and Jamaica has only one popular cultivar (Lawrence, Reference Lawrence1984).

Table 3 Cultivar diversity of ginger in India (revised from Sasikumar et al., Reference Sasikumar, Saji, Ravindran, Peter, Sasikumar, Krishnamurthy, Rema, Ravindren and Peter1999)

Words in parenthesis denote important states of cultivation.

a Improved variety

b Exotic.

Varietal improvement in ginger has been limited to germplasm selection for high yield and better quality attributes besides some mutation breeding and ploidy breeding. So far nine improved ginger varieties (‘Varada,’ ‘Mahima’, ‘Rejatha’, ‘Suruchi’, ‘Suravi’, ‘Suprabha’, ‘Himgiri’, ‘Athira’ and ‘Karthika’) were released in India (Sasikumar et al., Reference Sasikumar, Saji, Antony, George, John Zachariah and Eapen2003, Reference Sasikumar, Krishnamurthy, Kandiannan, Srinivasan, Dinesh, Shiva, Prasath, Babu and Parthasarathy2007) and one (‘Buderim Gold’) from Australia (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Hamill, Gogel and Severn-Ellis2004).

Characterization of ginger

Morphological and anatomical characterization

Variability for yield, quality traits and rhizome features has been reported in ginger (Khan, Reference Khan1959; Thomas, Reference Thomas1966; Krishnamurthy et al., Reference Krishnamurthy, Mathew, Nambudiri and Lewis1972; Muralidharan and Kamalam, Reference Muralidharan and Kamalam1973; Mohanty and Sharma, Reference Mohanty and Sharma1979; Nybe and Nair, Reference Nybe and Nair1979; Nybe et al., Reference Nybe, Nair, Mohanakumaran, Nair, Premkumar, Ravindran and Sarma1980; Sreekumar et al., Reference Sreekumar, Indrasenan, Mamman, Nair, Premkumar, Ravindran and Sarma1980; Kumar et al., Reference Kumar, Balasubramanian, Kumar and Mammen1980; Mohanty et al., Reference Mohanty, Das and Sharma1981; Rattan et al., Reference Rattan, Korla, Dohroo, Satyanarayana, Reddy, Rao, Azam and Naidu1988; Arya and Rana, Reference Arya and Rana1990; Sasikumar et al., Reference Sasikumar, Nirmal Babu, Abraham and Ravindran1992; Zachariah et al., Reference Zachariah, Sasikumar and Ravindran1993; Ravindran et al., Reference Ravindran, Sasikumar, George, Ratnambal, Nirmal Babu, Zachariah and Nair1994; Sasikumar et al., Reference Sasikumar, Ravindran and George1994, Reference Sasikumar, Saji, Ravindran, Peter, Sasikumar, Krishnamurthy, Rema, Ravindren and Peter1999, Reference Sasikumar, Saji, Antony, George, John Zachariah and Eapen2003; Aiyadurai, Reference Aiyadurai1996; John and Ferreira, Reference John and Ferreira1997; Chandra and Govind, Reference Chandra and Govind1999; Yadav, Reference Yadav1999; Zachariah et al., Reference Zachariah, Sasikumar, Nirmal Babu, Sasikumar, Krishnamurthy, Rema, Ravindren and Peter1999; Singh et al., Reference Singh, Singh, Singh and Singh1999; Singh et al., Reference Singh, Singh, Singh and Rajan2000; Gowda and Melanta, Reference Gowda, Melanta, Muraleedharan and Rajkumar2000; Mohandas et al., Reference Mohandas, Pradeep Kumar, Mayadevi, Aipe and Kumaran2000; Naidu et al., Reference Naidu, Padma, Yuvaraj and Murty2000; Singh, Reference Singh2001; Tiwari, Reference Tiwari2003; Abraham and Latha, Reference Abraham and Latha2003; Rana and Korla, Reference Rana and Korla2007; Lincy et al., Reference Lincy, Jayarajan and Sasikumar2008) (Fig. 1). Primitive types (obsolete cultivars) in general are characterized by small rhizomes; poor yield and better quality although the cultivars/improved varieties possess attractive bold rhizomes with good yield and mixed quality traits. Ginger cultivars/varieties suited for various end uses are given as Table S1, available online only at http://journals.cambridge.org. However, yield and quality levels in ginger also vary with genotypes, soil types, locations, seasons, cultural practices and climatic conditions.

Fig. 1 Variability for rhizome features in Indian ginger germplasm (a) ‘Varada’, (b) ‘Mahima’, (c) ‘Rejatha’, (d) ‘Suprabha’, (e) ‘Sabarimala’, (f) ‘Kozhikkalan’, (g) ‘Kakakalan’, (h) ‘Ellakallan’, (i) ‘Nadia’, (j) ‘Rio-de-Janeiro’, (k) ‘Silent valley’ and (l) ‘Himachal’.

Ginger (Z. officinale) has distinct anatomical features such as absence of periderm, short lived functional cambium, occurrence of xylem vessels with scalariform thickening in the rhizome compared with Z. zerumbet, Z. roseum and Z. macrostachyum (Ravindran et al., Reference Ravindran, Remasree and Sherlija1998).

Molecular characterization

RAPD (random amplified polymorphic DNA), AFLP (amplified fragment length polymorphism), ISSR (inter simple sequence repeats), simple sequence repeats markers and isozymes have been used to characterize ginger germplasm. Sasikumar et al. (Reference Sasikumar, John and Shamina2000) evaluated 14 accessions of ginger from different regions of India for variations in acid phosphatase, polyphenol oxidase, super oxide dismutase (SOD) and peroxidase (PRX). Among them, acid phosphatase showed maximum number of bands followed by SOD, while PRX had the least bands. Though variability in the population was very low, the accessions from Kerala region (southern India) were distinct from those collected from the north-east Indian states suggesting a geographical bias of the germplasm studied. A total of 28 ginger cultivars from China were compared for PRX isoenzyme patterns by fuzzy cluster analysis (Chengkun et al., Reference Chengkun, Jiashen, Suzhi, Min and Wensheng1995). The cultivars differed in zonal number, activity intensity and isoenzyme pattern, which were related to rhizome size, growth intensity and blast (blight?) (Ralstonia solanacearum) resistance. The cultivars from the Fujian Province were more diverse.

Muda et al. (Reference Muda, Halijah and Norzulaani2004) studied the genetic variation among three Z. officinale cultivars/subspecies i.e. Z. officinale var. officinale, Z. officinale var. rubra (‘halia bara’) and Z. officinale var. rubrum (‘halia padi’) using RAPD analysis and cultivar-specific markers were obtained. Similarly, Nayak et al. (Reference Nayak, Naik, Acharya, Mukherjee, Panda and Das2005) based on their study of 16 ginger cultivars from India showed that RAPD primers OPC02, OPD20 and OPN06 had strong resolving powers and were able to distinguish all cultivars. However, Palai and Rout (Reference Palai and Rout2007) found that of the eight Indian landraces/varieties of ginger (‘Surabhi’, ‘Tura Local’, ‘Jugijan’, ‘Nadia’, ‘S-558’, ‘Gorubathani’, ‘ZO-17’ and ‘Nangrey’) all but one formed a single cluster in the dendrogram. Molecular characterization of seven ginger accessions including primitive, exotic and elite ones using 14 ISSR and 16 RAPD markers by Prem et al. (Reference Prem, Kizhakkayil, Thomas, Dhanya, Syamkumar and Sasikumar2007) also showed that the four primitive gingers (‘Kozhikkalan’, ‘Kakkakalan’, ‘Ellakkallan’ and ‘Sabarimala’) formed one cluster while all others were separately clustered in the dendogram. In another molecular characterization study using 25 RAPD primers Zhen-wei et al. (Reference Zhen-wei, Shou-Jin Fan, De-min GAO, Zhen-wei LIU and Shou-jin FAN2006) reported a narrow genetic base among 20 Chinese cultivars.

AFLP markers were used to study the genetic relationship among three Indonesian type gingers (big ginger, small ginger and red ginger) (Wahyuni et al., Reference Wahyuni, Xu, Bermawie, Tsunematsu and Ban2003). In this analysis, 28 accessions including those from Africa and Japan were used. Red ginger was genetically distinct from the big ginger, but close to some accessions of small ginger. There was no clear genetic differentiation between the small and big types ginger. Lee et al. (Reference Lee, Fai, Zakaria, Ibrahim, Othman, Gwang, Rao and Park2007) isolated and characterized eight polymorphic microsatellite markers. A total of 34 alleles were detected across 20 ginger accessions, with an average of 4.3 alleles per locus. This study revealed the existence of moderate level of genetic diversity among the ginger accessions genotyped.

Recently, Kizhakkayil and Sasikumar (Reference Kizhakkayil and Sasikumar2010) characterized 46 accessions using 30 RAPD and 17 ISSR markers. Unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean dendrograms based on three similarity coefficients (Jaccard's, Sorensen–Dice and Simple Matching) placed the accessions in four similar clusters and revealed less genetic distance among the accessions. Improved varieties/cultivars were grouped together with primitive types. In the clustering pattern of the accessions, a geographical bias was also evident implying that germplasm collected from nearby locations with local identity may not be genetically distinct. The clustering of the accessions was largely independent of its agronomic features.

The different molecular markers in general revealed low level of polymorphism (Figs. 2 and 3) and only moderate variability with some exceptions, among the ginger accessions studied probably due to the confounded effect of the duplicate accessions in the genebank.

Fig. 2 RAPD profile of the DNA isolated from different ginger accessions amplified with primer OPA 07. M-marker; lane 1–46 ‘Varada’, ‘Mahima’, ‘Rejatha’, ‘Suruchi’, ‘Suprabha’, ‘Himachal’, ‘Maran’, ‘Nadia’, ‘Karakkal’, ‘Mananthodi’, ‘Sabarimala’, ‘Kozhikkalan’, ‘Ellakkallan’, ‘Kakakalan’, ‘Pakistan’, ‘Oman’, ‘Brazil’, ‘Jamaica’, ‘Rio-de-Janeiro’, ‘Pink ginger’, ‘Bakthapur’, ‘Kintoki’, ‘Nepal’, ‘China’, ‘Jugijan’, ‘Acc. no. 50’, ‘Pulpally’, ‘Acc. no. 95’, ‘Ambalawayalan’, ‘Kozhikode’, ‘Thodupuzha-1’, ‘Konni local’, ‘Angamali’, ‘Thodupuzha-2’, ‘Kottayam’, ‘Palai’, ‘Silent valley’, ‘Wayanad local’, ‘Vizagapatnam-1’, ‘Vizagapatnam-2’, ‘Fiji’, ‘Gorubathani’, ‘Bhaise’, ‘Naval parasi’, ‘Neyyar’, ‘Jolpaiguri’, respectively.

Fig. 3 ISSR profile of the DNA isolated from different ginger accessions amplified with primer ISSR3. M-marker; lane 1–46 ‘Varada’, ‘Mahima’, ‘Rejatha’, ‘Suruchi’, ‘Suprabha’, ‘Himachal’, ‘Maran’, ‘Nadia’, ‘Karakkal’, ‘Mananthodi’, ‘Sabarimala’, ‘Kozhikkalan’, ‘Ellakkallan’, ‘Kakakalan’, ‘Pakistan’, ‘Oman’, ‘Brazil’, ‘Jamaica’, ‘Rio-de-Janeiro’, ‘Pink ginger’, ‘Bakthapur’, ‘Kintoki’, ‘Nepal’, ‘China’, Jugijan’, ‘Acc. No. 50’, ‘Pulpally’, ‘Acc. No. 95’, ‘Ambalawayalan’, ‘Kozhikode’, ‘Thodupuzha-1’, ‘Konni local’, ‘Angamali’, ‘Thodupuzha-2’, ‘Kottayam’, ‘Palai’, ‘Silent valley’, Wayanad local’, ‘Vizagapatnam-1’, ‘Vizagapatnam-2’, ‘Fiji’, ‘Gorubathani’, ‘Bhaise’, ‘Naval parasi’, ‘Neyyar’, ‘Jolpaiguri’, respectively.

Biochemical characterization

Characterization of ginger for the major biochemical constituents viz. oleoresin, essential oil and crude fibre levels has lead to identification of cultivars rich in one or other of these constituents (Table S1, available online only at http://journals.cambridge.org). Oleoresin content of ginger varied from 3 to 11% depending on the genotype, solvent extraction condition, state of rhizome, place of origin and harvest season (Ratnambal et al., Reference Ratnambal, Gopalam and Nair1987; Vernin and Parkanyl, Reference Vernin, Parkanyl, Ravindran and Nirmal Babu2005).

Crude fibre content of dried ginger ranged from 4.8 to 9% (Natarajan et al., Reference Natarajan, Kuppuswamy, Shankaracharya, Padmabai, Raghavan, Krishnamurthy, Khan, Lewis and Govindarajan1972) although essential oil content of ginger varied from 0.2 to 3%, depending on the origin and state of rhizome (van Beek et al., Reference van Beek, Posthumus, Lelyveld, Hoang and Yen1987; Ekundayo et al., Reference Ekundayo, Laakso and Hiltunen1988). Characterization of 46 ginger accessions revealed that the primitive type gingers such as ‘Sabarimala’, ‘Kozhikkalan’ and ‘Kakakalan’ as well as few landraces have higher levels of oleoresin and essential oil compared with the improved varieties. (Kizhakkayil and Sasikumar, Reference Kizhakkayil and Sasikumar2009). Menon (Reference Menon2007) too has observed that primitive ginger types such as ‘Kozhikkalan’ and ‘Vellinchi’ are rich in essential oil content. Shing Bhukir, a primitive type ginger from Meghalaya, India, is sold at a premium price for its medicinal value (Rahman et al., Reference Rahman, Karuppaiyan, Kishore and Denzongpa2009). ‘Kintoki’, a landrace from Japan, has very low fibre content (Kizhakkayil, Reference Kizhakkayil2008). Indian ginger cultivars are known to vary for the pungent and non-pungent constituents: gingerol and shogaol (Zachariah et al., Reference Zachariah, Sasikumar and Ravindran1993) though lack of variability for gingerol and shogaol has been observed in Australian ginger (Wohlmuth et al., Reference Wohlmuth, Leach, Smith and Myers2005). High levels of ar-curcumene and β-bisabolene with reasonable levels of citral isomers and very low levels of zingiberene were observed in dried Sri Lankan ginger (Macloed and Pieris, Reference Macloed and Pieris1984).

In short, the volatile and/or non-volatile compounds of ginger are affected by the environment and the state of rhizome (Connel and Jordan, Reference Connel and Jordan1971; Macloed and Pieris, Reference Macloed and Pieris1984; Ekundayo et al., Reference Ekundayo, Laakso and Hiltunen1988; Menut et al., Reference Menut, Lamaty, Bessiere and Koudou1994; Vernin and Parkanyl, Reference Vernin, Parkanyl and Charalambous1994; Fakim et al., Reference Fakim, Maudarbaccus, Leach, Doimo and Wohlmuth2002; Wohlmuth et al. Reference Wohlmuth, Smith, Brooks, Myers and Leach2006). However, a wide variability in the essential oil profile of ginger is unseen though there are few odd cultivars/primitive types excelling in one or the other compounds including the pungent constituents.

Characterization against pests

Bacterial wilt (R. solanacearum), soft rot (Pythium spp.) and shoot borer (Conogethes punctiferalis) are three major pests of ginger. No stable bacterial wilt resistant ginger cultivar is known to exist. Consistent with this, 600 accessions screened for bacterial wilt tolerance using soil inoculation method were found susceptible (Kumar and Hayward, Reference Kumar, Hayward, Ravindran and Nirmal Babu2005). However, Shylaja et al. (Reference Shylaja, Paul, Nybe, Abraham, Nazeem, Nazeem, Valsala and Krishnan2010) reported that the ginger clone ‘Athira’ is relatively more tolerant to bacterial wilt and soft rot than its mother clone ‘Maran’. Clones ‘Maran’ ‘Suprabha’ and ‘Himachal’ have been reported to show field tolerance to ginger rot (Pythium aphanidermatum) (Indrasenan and Paily, Reference Indrasenan and Paily1974; Setty et al., Reference Setty, Guruprasad, Mohan and Reddy1995).

Nybe and Nair (Reference Nybe and Nair1979a) while recording shoot borer incidence in 25 ginger cultivars reported cultivar ‘Rio de Janeiro’ with minimum incidence. Devasahayam et al. (Reference Devasahayam, Jacob, Koya and Sasikumar2010) could not find any shoot borer resistant lines in 592 ginger accessions screened though 49 accessions were rated as moderately resistant.

Uses

Products and end uses

Ginger imparts flavour and pungency to food and beverages (Arctangder, Reference Arctangder1960; Pruthy, Reference Pruthy1993; Bakhru, Reference Bakhru1999). Flavour properties of ginger depend on both volatile and non-volatile fractions. Fresh succulent baby pink ginger, salted ginger, crushed fresh ginger, dry ginger, ginger powder, ginger oil, ginger oleoresin, dry soluble ginger, ginger paste and ginger emulsion are used in different preparations. Fresh young ginger, succulent in nature with low fibre content is preferred for products such as ginger candy, preserves, and salted ginger while mature fresh ginger is used for preparing ginger shreds, the ethnic ginger chutney, ginger tea and ginger curry (Inchi puli). Ginger is an indispensable component of curry powder, sauces, ginger bread and ginger flavoured carbonated drinks (Hirara and Takesma, Reference Hirara and Takesma1998) in addition to its use in biscuits, pickles, confectionaries and other dietary preparations.

Ginger in medicine

Ayurveda recommends ginger as a carminative, diaphoretic, antispasmodic, expectorant, peripheral circulatory stimulant, astringent, appetite stimulant, anti-inflammatory agent, diuretic and digestive aid (Warrier, Reference Warrier, George, Sivadasan, Devakaran and Sreekumari1989). Recent pharmacological studies attest this age-old medicinal value of ginger (Aimbire et al., Reference Aimbire, Penna, Rodrigues, Rodrigues, Lopes-Martins and Sertié2007; Ansari and Bhandari, Reference Ansari and Bhandari2008; Morakinyo et al., Reference Morakinyo, Adeniyi and Arikawe2008; Heimes et al., Reference Heimes, Feistel and Verspohl2009; Nammi et al., Reference Nammi, Satyanarayana and Roufogalis2009, Reference Nammi, Kim, Gavande, Li and Roufogalis2010; Lakshmi and Sudhakar, Reference Lakshmi and Sudhakar2010). Ginger is recommended to expecting women as an antenatal medicine as well as to alleviate the ‘morning sickness’ during pregnancy (Ozgoli et al., Reference Ozgoli, Goli and Simbar2009; Broussard et al., Reference Broussard, Louik, Honein and Mitchell2010) and motion sickness. Trikatu is a favourite carminative remedy prepared with equal portions of Z. officinale, Piper nigrum and Piper longum (Anonymous, Reference Raghunathan and Roma Mitra1982). Ginger is the major constituent in formulations including Chatarbhada Kvatha used against fever and respiratory disorders; in antitussive drug Lavangadhichurn and in Hingvastaka churna recommended for indigestion (Singh, Reference Singh1983; Thakur et al., Reference Thakur, Puri and Akhtar Husain1989).

Ginger is also a major ingredient in Unani preparations such as ‘Hub-gul-pista’, an expectorant, ‘Sufuf-shirin’ an anti-dysenteric drug and ‘Majun Izuroqui’ a geriatric tonic as well as in the ginger based carminatives ‘Qurs Pudina’ and ‘Murraba Adrak’ (Singh, Reference Singh1983; Thakur et al., Reference Thakur, Puri and Akhtar Husain1989).

Chinese medicine too value ginger since 4th century BC (Wagner and Hikino, Reference Wagner and Hikino1965). The Chinese administer ginger for a wide variety of medical problems such as stomachache, headache, diarrhoea, nausea, cholera, asthma, heart conditions, respiratory disorders, toothache and rheumatic complaints (Wagner and Hikino, Reference Wagner and Hikino1965; Grant and Lutz, Reference Grant and Lutz2000). Africans and West Indians also use ginger for many ailments (Tyler et al., Reference Tyler, Brady and Robbers1981). Ginger has been used in the Mediterranea for treatment of arthritis, rheumatological problems and muscular discomfort (Langner et al., Reference Langner, Greifenberg and Gruenwald1998; Sharma and Clark, Reference Sharma and Clark1998). It has also been recommended for the treatment of various other conditions including atherosclerosis, migraine, rheumatoid arthritis, high cholesterol, ulcers, depression and impotence (Liang, Reference Liang1992).

In folk/ethnic medicine too ginger is indispensable. Fresh ginger juice is administered to pregnant women just before childbirth for easy delivery (Rao and Jamir, Reference Rao and Jamir1982). Ginger is an ethnic remedy for pain, rheumatism, mad convulsion, collapse, scabies, constipation, indigestion, prolepsis, fistula, cholera, throat pain, tuberculosis, cold, fever and cough (Jain and Tarafder, Reference Jain and Tarafder1970; Anonymous, 1978). Ginger along with P. longum is used as an abortifacient in some tribes (Tarafder, Reference Tarafder1983).

In veterinary medicine too ginger is important against many livestock maladies. Iqbal et al. (Reference Iqbal, Latheef, Akhtar, Ghayur and Gilani2006) reported the anthelmintic activity of crude powder and crude aqueous extract of dried ginger in sheep naturally infected with gastrointestinal nematodes.

Pharmacology

Both the volatile and non-volatile compounds of ginger are credited with medicinal properties besides imparting pungency and aroma to ginger as a spice (Fig. S1, available online only at http://journals.cambridge.org). The main volatile compounds are mono- and sesqui-terpenes, camphene, phellandrene, curcumene, cineole, geranyl acetate, terphineol, terpenes, borneol, geraniol, limonene, linalool, zingiberene, sesqui-phellandrene, bisabolene and farnesene. Many of these compounds are credited with curative properties. (Feng and Lipton, Reference Feng and Lipton1987; Zebovitz, Reference Zebovitz, Keith and Walters1989; Keeler and Tu, Reference Keeler and Tu1991; Yamahara et al., Reference Yamahara, Hatakeyama, Taniguichi, Kawamura and Yoshikawa1992; Hansel et al., Reference Hansel, Keller, Rimpler and Schneider1992; Reddey and Lokesh, Reference Reddey and Lokesh1992; Martin et al., Reference Martin, Padilla, Ocete, Galvez, Jimenez and Zarzuelo1993; Denyer et al., Reference Denyer, Jackson, Loakes, Ellis and Yound1994; Leung and Foster, Reference Leung and Foster1995; Newall et al., Reference Newall, Anderson and Phillipson1996; Obeng-Ofori and Reichmuth, Reference Obeng-Ofori and Reichmuth1997; Blascheck et al., Reference Blascheck, Hansel, Keller, Reichling, Rimpler and Schneider1998; Atsumi et al., Reference Atsumi, Fujisawa, Satoh, Sakagami, Iwakura, Ueha, Sugita and Yokoe2000; Coppen, Reference Coppen2002; Murakami et al., Reference Murakami, Shoji, Hanazawa, Tanaka and Fujisawa2003; Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Tang, Mao and Bian2004; Juergens et al., Reference Juergens, Engelen, Racké, Stöber, Gillissen and Vetter2004; Masuda et al., Reference Masuda, Kikuzaki, Hisamoto and Nakalani2004; Ali et al., Reference Ali, Khan, Ahmed, Musaddiq, Ahmed, Polasa, Rao, Habibullah and Sechi2005; Hsu et al., Reference Hsu, Kuo, Chen, Chung, Lai and Huang2005; Kuo et al., Reference Kuo, Dhamu, Cheng, Teng, Lee and Wu2005; Shin et al., Reference Shin, Kim, Chung and Jeong2005; Rao and Rao, Reference Rao and Rao2005; Riyazi et al., Reference Riyazi, Hensel, Bauer, Geissler, Schaaf and Verspohl2007; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Huang, Wu, Kuo, Ho and Hsiang2007; Shukla and Singh, Reference Shukla and Sing2007; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Kang, Park, Moon, Sim and Kim2009; El-Baroty et al., Reference El-Baroty, El-Baky, Farag and Saleh2010; Hsu et al., Reference Hsu, Chen, Hou, Tsai, Jong, Hung and Kuo2010). β-Phellandrene and zingiberene are the major compounds in Indian commercial gingers. Ginger oil per se is also having antiulcer, antidepressant and anti-inflammatory properties (Sharma et al., Reference Sharma, Ishak, Yusof and Srivastava1997; Khushtar et al., Reference Khushtar, Kumar, Javed and Uma Bhandari2009; Qiang et al., Reference Qiang, Wang, Wang, Pan, Yi, Zhang and Kong2009).

The major non-volatile pungent compounds of ginger, the gingerols and shogaols, too possess analgesic, antipyretic, cardio tonic, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory properties besides suppressing cytokine formation and promoting angiogenesis. (Mascolo et al., Reference Mascolo, Jain, Jain and Capasso1989; Yamahara et al., Reference Yamahara, Rong, Iwamoto, Kobayashi, Matsuda and Fujimura1989; Yamahara and Huang, Reference Yamahara and Huang1990; Huang et al., Reference Huang, Iwamoto, Aoki, Tanaka, Tajima, Yamahara, Takaishi, Yoshida, Tomimatsu and Tamai1991; Mustafa et al., Reference Mustafa, Srivastava and Jensen1993; Lee and Surh, Reference Lee and Surh1998; Surh et al., Reference Surh, Lee and Lee1998; Surh, Reference Surh1999; Bhattarai et al., Reference Bhattarai, Tran and Duke2001; Chung et al., Reference Chung, Jung, Surh, Lee and Park2001; Ficker et al., Reference Ficker, Smith, Akpagana, Gbeassor, Zhang, Durst, Assabgui and Arnason2003; Jolad et al., Reference Jolad, Lantz, Solyom, Chen, Bates and Timmermann2004; Isa et al., Reference Isa, Miyakawa, Yanagisawa, Goto, Kang, Kawada, Morimitsu, Kubota and Tsuda2008; Pan et al., Reference Pan, Hsieh, Kuo, Lai, Wu, Sang and Ho2008; Park et al., Reference Park, Lee, Son and Youn2009; Koh et al., Reference Koh, Kim, So, Choi, Choi, Ryu, Kim, Koh and Park2009; Imm et al., Reference Imm, Zhang, Chan, Nitteranon and Parkin2010). Gingerol, particularly 6-gingerol, has been found to be the most active compound biologically (Yamahara et al., Reference Yamahara, Rong, Iwamoto, Kobayashi, Matsuda and Fujimura1989; Mascolo et al., Reference Mascolo, Jain, Jain and Capasso1989; Huang et al., Reference Huang, Iwamoto, Aoki, Tanaka, Tajima, Yamahara, Takaishi, Yoshida, Tomimatsu and Tamai1991; Mustafa et al., Reference Mustafa, Srivastava and Jensen1993; Aeschbach et al., Reference Aeschbach, Löliger, Scott, Murcia, Butler, Halliwell and Aruoma1994; Agarwal et al., Reference Agarwal, Walia, Dhingra and Khambay2001; Ficker et al., Reference Ficker, Smith, Akpagana, Gbeassor, Zhang, Durst, Assabgui and Arnason2003; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Kundu, Shin, Park, Cho, Kim and Surh2005; Tripathi et al., Reference Tripathi, Tripathi, Maier, Bruch and Kittur2006; Lam et al., Reference Lam, Woo, Leung and Cheng2007; Sjmonatj, Reference Sjmonatj2009; Jeong et al., Reference Jeong, Bode, Pugliese, Cho, Kim, Shim, Jeon, Li, Jiang and Dong2009; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Hsieh, Lo, Liu, Sang, Ho and Pan2010; Yang et al., Reference Yang, Zhong, Jiang, Geng, Cao, Sun and Ma2010).

Biologically active compounds of ginger are given in the Table S2, available online only at http://journals.cambridge.org.

Ginger has strong antibacterial and to some extent antifungal properties too (Kapoor, Reference Kapoor1997; Habsah et al., Reference Habsah, Amran, Mackeen, Lajis, Kikuzaki, Nakatani, Rahman, Ghafar and Ali2000; Srinivasan et al., Reference Srinivasan, Nathan, Suresh and Lakshmana Perumalsamy2001). In vitro studies have shown that active constituents of ginger inhibit multiplication of colon bacteria (Bakhru, Reference Bakhru1999). Ginger also inhibits the growth of Escherichia coli, Proteus spp., Staphylococci, Streptococci and Salmonella (Gugnani and Ezenwanze, Reference Gugnani and Ezenwanze1985; James et al., Reference James, Nannapaneni and Johnson1999). O'Mahony et al. (Reference O'Mahony, Al-Khtheeri, Weerasekera, Fernando, Vaira, Holton and Christelle2005) reported curative effects against Helicobacter pylori. Fresh ginger juice showed inhibitory action against Aspergillus niger, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Mycoderma spp. and Lactobacillus acidophilus at 4, 10, 12 and 14%, respectively, at ambient temperatures (Nanir and Kadu, Reference Nanir and Kadu1987; Meena, Reference Meena1992; Kapoor, Reference Kapoor1997). Martins et al. (Reference Martins, Salgueiro, Goncalves, da Cunha, Vila and Canigueral2001) demonstrated antimicrobial activity of essential oil against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria using agar diffusion method.

Conclusion

Ginger is one of the most important and ancient spices. Though ginger is sterile, plentiful cultivar diversity, recognized mostly by local names exists. However, most of the molecular/biochemical characterization studies attempted so far failed to reveal significant polymorphism commensurating with the observed morphological variability or yield. A geographical bias in the ginger germplasm conserved in the ex situ genebanks, probably due to local (vernacular) identity problems during germplasm collection and the geographical effect on key constituents are the hallmark of most of the germplasm characterization studies. Variability for the essential oil profile as well as the pungent constituents is also not that remarkable though few primitive cultivars with excellent quality traits have been reported from different countries. The primitive types (obsolete cultivars), invariably poor yielders on the verge of extinction, require special attention in long-term conservation strategy especially because convergent improvement or hybridization is rather difficult in a sterile ginger. Pharmacokinetic studies on the long-term effect of the curative compounds are still in infancy. Taxonomic and pharmacological studies on the subspecies of Z. officinale will also be rewarding. In future, there may be premium for tailor-made ginger varieties to meet a specific end use. Thus, research on the effect of environmental factors including the changing climate on quality profile and aroma of ginger, pharmacokinetics of the medicinally important constituents, problem of sterility and above all a comprehensive characterization study on the global germplasm should assume priority.