Introduction

Reduction of genetic variability in many crops is becoming a serious threat to the future of agriculture. Selection pressure exerted by humans during domestication has caused bottlenecks that have led to a progressive narrowing of the genetic base in the most important staple crops (Tanksley and McCouch, Reference Tanksley and McCouch1997; Warburton et al., Reference Warburton, Crossa, Franco, Kazi, Trethowan, Rajaram, Pfeiffer, Zhang, Dreisigacker and van Ginkel2006). Increasing variability is a major objective in plant breeding. Regarding wheat, primitive ancestors or wild relatives reveal themselves to be underutilized sources of genetic variability. Among synthetic wheats (proceeding from crosses between durum wheat and the wild goat grass Aegilops tauschii), several have shown promising combinations resulting in higher yields, larger grains and new resistance or tolerance to abiotic and biotic stresses (van Ginkel and Ogbonnaya, Reference van Ginkel and Ogbonnaya2007). The potential of A. tauschii, the D-genome donor of bread wheat, has also been studied for the improvement of quantitative traits in bread wheat (Börner et al., Reference Börner, Schumann, Fürste, Cöster, Leithold, Röder and Weber2002; Huang et al., Reference Huang, Coster, Ganal and Röder2003, Reference Huang, Kempf, Ganal and Röder2004; Pestsova et al., Reference Pestsova, Börner and Röder2006). Wild species are also potential donors of exotic alleles for specific traits such as the leaf rust resistance in Lophopyrum ponticum (Podp.) Löve (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Lukaszewski, Kolmer, Soria, Goyal and Dubcovsky2005) or the high carotenoid content in Hordeum chilense Roem et Schultz. (Atienza et al., Reference Atienza, Ramirez, Hernandez and Martin2004; Atienza et al., Reference Atienza, Avila and Martín2007a, Reference Atienza, Ballesteros, Martin and Hornero-Mendezb; Rodríguez-Suárez et al., Reference Rodríguez-Suárez, Giménez and Atienza2010).

Durum wheat (Triticum turgidum, 2n = 4x = 28, AABB) can also benefit from ancient wheats and wild species. The interest in so-called ancient wheats such as rivet wheat (T. turgidum L. spp. turgidum) or khorasan wheat (T. turgidum spp. turanicum Jakubz em. A. Löve & D. Löve) has increased in the last few years (Piergiovanni, Reference Piergiovanni2009; Xu et al., Reference Xu, Li, Wei and Zheng2009; Carmona et al., Reference Carmona, Caballero, Martín and Alvarez2010). However, the variability available in the diploid progenitor of durum wheat has been mostly neglected to date. The allotetraploid durum wheat arose by amphiploidization between the wild diploid wheat Triticum urartu (2n = 2x = 14, AuAu) and an unknown diploid member of the Aegilops genus (2n = 2x = 14, BB), T. urartu being the A-genome donor of tetraploid and hexaploid wheats (Chapman et al., Reference Chapman, Miller and Riley1976). Thus, the Au genome is a near relative of the A genome, that may be a source of novel alleles lost during domestication as happens with other crops such as barley and its wild relative Hordeum vulgare subsp. spontaneum (Fetch et al., Reference Fetch, Steffenson and Nevo2003; Yun et al., Reference Yun, Gyenis, Hayes, Matus, Smith, Steffenson and Muehlbauer2005). Unlike barley, where both the wild and the cultivated species are diploid, durum wheat and T. urartu differ in the ploidy level, and, therefore, the variability of the latter cannot be used directly for durum wheat breeding. Hence, T. urartu has not been exploited for durum wheat improvement up to now even though it shows variability for many important agronomical traits such as endosperm storage proteins or resistance to biotic and abiotic stresses (di Pietro et al., Reference di Pietro, Caillaud, Chaubet, Pierre and Trottet1998; Qiu et al., Reference Qiu, Zhou, Kong, Zhang and Jia2005; Martín et al., Reference Martín, Martín and Alvarez2008). T. urartu would be an accessible source of wild variation to durum wheat. However, plant breeders know that agronomic performance suffers when exotic germplasm is introgressed into elite germplasm, which is attributed to epistasis and (or) linkage drag (Young and Tanksley, Reference Young and Tanksley1989; Lee, Reference Lee1998; Brondani et al., Reference Brondani, Rangel, Brondani and Ferreira2002). As proposed by Eshed and Zamir (Reference Eshed and Zamir1994), introgression lines (ILs) are an efficient resource to overcome these problems and to use the genetic potential of wild species in an effective way, allowing the detection of single traits or QTLs and their easy transfer into new materials.

In a previous work, the synthesis of the amphiploid between T. urartu and durum wheat cv. ‘Yavaros’ was reported (Alvarez et al., Reference Alvarez, Caballero, Nadal, Ramirez and Martín2009). Storage endosperm proteins (Glu-A1 locus) were effectively used for selecting towards durum wheat lines carrying T. urartu chromatin, and a subset of 20 pre-ILs was analyzed for some quality characters such as grain colour or gluten strength. However, the precise characterization of the introgression lines requires a wider set of molecular markers evenly distributed across the entire genome. Therefore, the objective of this work was to establish an effective set of molecular markers which would be useful for our pre-breeding programme that aims to use T. urartu for durum wheat breeding.

Material and methods

Plant material

Durum wheat cv. ‘Yavaros’, T. urartu accession MG26992, the amphiploid derived from the cross Yavaros × MG26992 and 98 pre-ILs were used. The strategy followed by Alvarez et al. (Reference Alvarez, Caballero, Nadal, Ramirez and Martín2009) for the development of the pre-ILs is summarized in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1 Development of the amphiploid between T. urartu and durum wheat and construction of the pre-introgression lines, as followed by Alvarez et al. (Reference Alvarez, Caballero, Nadal, Ramirez and Martín2009).

DNA isolation and simple sequence repeats analyses

Leaf tissue of ‘Yavaros’, T. urartu, the amphiploid and the 98 pre-ILs was harvested, frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at − 80°C until DNA extraction. Genomic DNA was extracted according to Murray and Thompson (Reference Murray and Thompson1980).

The amplification of 78 chromosome-specific simple sequence repeats (SSRs) from different sources was analyzed in the parents and in the amphiploid (Röder et al., Reference Röder, Korzun, Wendehake, Plaschke, Tixier, Leroy and Ganal1998; Somers et al., Reference Somers, Isaac and Edwards2004; Sourdille et al., Reference Sourdille, Singh, Cadalen, Brown-Guedira, Gay, Qi, Gill, Dufour, Murigneux and Bernard2004). PCR reactions were performed in a total 25 μl reaction mixture consisting of 50 ng of genomic DNA, 0.6 U of Taq (Biotools B&M Labs, Madrid), 1x PCR buffer, 1.6 mM MgCl2, 0.32 mM dNTPs (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) and 0.6 μM of each primer. PCR amplifications were optimized changing the number of cycles (n) and the annealing temperature using one of these two profiles: (1) an initial step of 94°C for 3 min, and then n cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 1 min at an annealing temperature ranging from 62 to 50°C and 72°C for 2 min, followed by 10 min at 72°C or (2) an initial step of 94°C for 5 min and then n cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 30 s at an annealing temperature ranging from 60 to 50°C and 72°C for 30 s, followed by 10 min at 72°C. PCR products were resolved on 2% agarose gels, stained with ethidium bromide and visualized under UV light.

Results

Selection of SSRs and optimization of PCR amplifications

A set of 78 wheat SSRs uniformly distributed over the A genome was selected for searching for polymorphism between ‘Yavaros’ and T. urartu (Supplementary Table S1, available online only at http://journals.cambridge.org). All markers (except for Xwmc658) are physically mapped to one breakpoint interval of chromosomes 1A to 7A in the Chinese Spring deletion lines (Sourdille et al., Reference Sourdille, Singh, Cadalen, Brown-Guedira, Gay, Qi, Gill, Dufour, Murigneux and Bernard2004). Ten to twelve SSRs were tested for each chromosome. Different PCR profiles were assayed using agarose to find polymorphism between alleles in chromosomes Au and A from T. urartu and ‘Yavaros’, respectively.

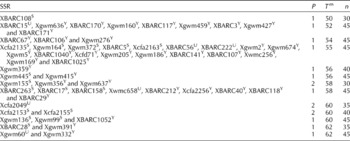

Twelve SSR markers (Xgwm328, Xgwm512, XBARC208, XBARC12, XBARC54, Xgwm32, XBARC1048, XBARC1047, XBARC153, Xcfa2187, XBARC165 and Xcfd82) did not show any clear and reproducible amplification pattern in our materials under different conditions and were not used further. Nine SSR markers (XBARC19, Xgwm480, XBARC78, XBARC186, Xgwm334, XBARC37, XBARC1088, Xcfa2028 and Xcfa2257) were monomorphic between T. urartu and ‘Yavaros’ under different amplification conditions in agarose. Finally, a set of 57 informative and reliable SSRs showing polymorphism between T. urartu and ‘Yavaros’ and covering the whole A genome was selected. Table 1 shows these SSR markers indicating the optimal PCR profile (see material and methods), number of cycles and annealing temperature.

Table 1 A set of 57 selected SSR markersa

a Their optimum profile (P, as detailed in material and methods), annealing temperature (T m) and number of cycles (n) are indicated. For each SSR, it is specified the genotype of the pre-ILs: if the allele of ‘Yavaros’ was present in all pre-ILs (Y), if it was the allele of T. urartu (U) or if the locus was segregating (S).

Molecular characterization of pre-ILs

The utility of the 57 selected SSRs for our marker-assisted selection programme was assessed in the set of 98 pre-ILs previously obtained (Supplementary Table S2, available online only at http://journals.cambridge.org). For six SSRs, the allele from T. urartu was present in all the pre-ILs (see SSR marker Xwmc658 in Fig. 2(d)). The allele from ‘Yavaros’ was present in all the pre-ILs at 35 SSR loci (see Xgwm674 in Fig. 2(c)). The remaining 16 polymorphic SSRs were segregating in the pre-ILs (see XBARC108 and Xgwm136 in Fig. 2(a),(b), respectively). Table 1 shows this information for each of the SSR markers. These results are also summarized in Table 2, where the exotic germplasm introgressed in ‘Yavaros’ is inferred by the presence of T. urartu alleles at each polymorphic loci analyzed. For chromosome 1A, it was possible to identify alleles proceeding from T. urartu for 100% of the SSRs tested within the set of pre-ILs. For chromosomes 2A and 7A, approximately at 50% of the loci (55.6 and 50%, respectively), alleles of T. urartu were identified. Lower rates of introgression were observed in chromosomes 3A and 5A, with 14.3 and 33.3%, respectively. Finally, no introgressions from T. urartu were detected in chromosomes 4A and 6A.

Fig. 2 Amplification of SSR markers XBARC108 (a), Xgwm136 (b), Xgwm674 (c) and Xwmc658 (d) in the following lines: (1) founder line, (2) T. turgidum ssp. durum cv. ‘Yavaros’, (3) T. urartu accession MG26992 and (4–19) pre-ILs 1–31.

Table 2 Exotic germplasm introgressed in durum wheat ‘Yavaros’, estimated by the presence of alleles of T. urartu at each of the polymorphic loci analyzed in chromosomes 1A to 7A within the 98 pre-ILs

a Determined as the ratio: loci with alleles from T. urartu/total polymorphic loci.

The set of SSRs selected for this work are useful for defining eighteen chromosomal reference points (CRPs), where introgressions of T. urartu into durum wheat have occurred in the pre-ILs. Introgressed fragments of T. urartu were identified in chromosomes 1A, 2A, 3A, 5A and 7A (Supplementary Table S2, available online only at http://journals.cambridge.org).

Discussion

In this work, we present a core collection of SSRs which have shown themselves to be very useful for different purposes: (1) Genotyping the pre-ILs: the strategic location of the 57 SSRs gives an overview of the genetic composition of the pre-ILs. Now, this valuable material is well characterized and ready to be used for research purposes by any durum wheat breeder; (2) defining CRPs: the selected SSRs define 18 CRP in chromosomes 1A, 2A, 3A, 5A and 7A (Supplementary Table S2, available online only at http://journals.cambridge.org), targeting the introgressed regions (3) estimating the introgression rates: the exotic germplasm introgressed can also be estimated with the information given by the molecular markers (Table 2). The founder line had been selected according to the presence of variants from T. urartu at Glu-A1 locus (Alvarez et al., Reference Alvarez, Caballero, Nadal, Ramirez and Martín2009), located in chromosome 1A (Payne et al., Reference Payne, Law and Mudd1980; Lawrence and Shepherd, Reference Lawrence and Shepherd1981). The selection pressure exerted has been very effective as revealed by the introgression rates observed in chromosome 1A, where the highest variation derived from T. urartu has been identified (Table 2 and Supplementary Table S2, available online only at http://journals.cambridge.org). Indeed, alleles from T. urartu were detected at all the loci tested in chromosome 1A within the set of pre-ILs. Therefore, a single selection step during the development of the founder line using protein markers was enough to maximize the variation within chromosome 1A, while reducing the variability in the rest of the chromosomes, as expected. For the rest of the chromosomes (where selection has not been exerted), introgressions have occurred at random, and, obviously, the introgressions present in the pre-ILs depend on the genotype of the founder line selected. This results in moderate or low introgression rates (in chromosomes 2A and 3A, respectively) or in no introgressions events at all (the case of chromosome 6A). Regarding chromosome 4A, the absence of introgressions of T. urartu can be explained because, as has been described (Chapman et al., Reference Chapman, Miller and Riley1976; Dvořák, Reference Dvořák1976), neither chromosome 4A nor chromosome 4B of wheat pairs with any of the T. urartu chromosomes; (4) marker-assisted selection: marker-assisted selection will enable the isolation of introgressions from T. urartu to obtain a set of ILs for chromosome 1A. In addition, it would be expectable that repeating the backcross between the amphiploid and durum wheat, selecting for chromosome number and using these SSR markers, the variability found in a specific chromosome would be maximized, while the number of introgressions in the other chromosomes would be reduced. Thus, a single selection step would suffice to increase the efficiency of introgression of any T. urartu chromosome into durum wheat by selecting new founder lines.

There is increasing evidence of the presence of beneficial alleles in the wild relatives which are hidden by other deleterious alleles (Huang et al., Reference Huang, Coster, Ganal and Röder2003; Matus et al., Reference Matus, Corey, Filichkin, Hayes, Vales, Kling, Riera-Lizarazu, Sato, Powell and Waugh2003). This natural variation available in the wild ancestors can be exploited in durum wheat. T. urartu may be useful for durum wheat breeding since it is possible to develop ILs using an amphiploid as a genetic bridge. Considering the success of synthetic wheats, it would seem of interest to develop similar programmes for durum wheat using T. urartu. From the present study, a set of 57 polymorphic A-genome wheat-specific markers have been identified as being useful for T. urartu-wheat marker-assisted introgression breeding. These results would allow a more effective selection of new ILs aiming to maximize variability in other chromosomes for genetic studies.

Acknowledgements

This work has been performed with the financial support of the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (AGL2009-11359) and the Consejería de Economía, Innovación y Ciencia of the Junta de Andalucía (P09-AGR-4817) and FEDER. C. R.-S. acknowledges financial support from CSIC (JAE-Doc program). We are grateful to E. León for her technical assistance.