1 Introduction

Phonological alternations can be conditioned by a number of factors, both phonological and non-phonological. Not all phonological alternations apply across the board in a language, even when the appropriate phonological context is present. For example, English velar softening of /k/ to [s] only applies before certain /ɪ/-initial suffixes (e.g. -ity, -ism), but not others (e.g. -ish, -ing). The identity of the morpheme, not just the phonological context, is relevant for determining whether velar softening applies. Other phonological alternations are sensitive to lexical class, such as nouns vs. verbs (Smith Reference Smith, van Oostendorp, Ewen, Hume and Rice2011), native words vs. loanwords (Kiparsky Reference Kiparsky, van der Hulst and S. H. Smith1982, Itô & Mester Reference Itô, Mester and Goldsmith1995) or seemingly arbitrary lexical items (Lightner Reference Lightner and Worth1972, Pater Reference Pater and Parker2009).

This paper distinguishes phonological conditioning factors from non-phonological ones, and describes a set of phonological alternations that require two non-phonological triggers to be present simultaneously. In each case study, two or more independent triggering morphemes must be present in the same domain of phonological evaluation in order for a particular phonological alternation to apply. For example, in Guébie (Kru, Ivory Coast), full vowel harmony applies only for a subset of lexical items, and only in the presence of a 3rd person object enclitic: /bala3.3==ɛ2/ ‘hit-3sg.acc’ → [bɛlɛ3.2] ‘hit it’. The process fails to apply in the environment of other phonologically identical affixes, and does not affect other roots. Both an alternating root and a triggering morpheme must be present for harmony to surface.

Numerous frameworks have been proposed to model morphologically conditioned phonology – many of which are discussed in §4. These frameworks struggle to account for morphologically conditioned phonology with two triggers. The relevant challenges for any framework of the morphology–phonology interface are to prevent (i) the phonological alternation from applying when just one of the two triggers is present, and (ii) alternation when a domain boundary intervenes between triggers. Here I contrast previous approaches with Cophonologies by Phase (CBP) Theory (Sande & Jenks Reference Sande and Jenks2018, Sande Reference Sande2019a, Sande et al. Reference Sande, Jenks and Inkelas2020), which associates morpheme-specific constraint-weight adjustments with vocabulary items, and assumes that morphology and phonology apply cyclically at syntactic phase boundaries. Cophonologies by Phase is restrictive, making specific predictions about the possible scope of morpheme-specific phonological alternations. In particular, phonological alternations triggered by a morpheme will not affect material introduced in hierarchically higher syntactic phases. There is some debate about the universality of phase boundaries. I rely throughout on language-specific diagnostics for phase boundaries where there is enough data available to do so. When there is not, I adopt the widely accepted view that at least D, Voice and C are phase heads.Footnote 1

Previous work in CBP has shown that it can model a wide range of phenomena, including phrasal or cross-word phonology triggered by specific morphemes, as well as category-specific phonology (Sande & Jenks Reference Sande and Jenks2018, Sande et al. Reference Sande, Jenks and Inkelas2020) and long-distance harmony and tone-spreading processes whose scope is limited by syntactic boundaries (Sande Reference Sande2019a), as well as local morphologically conditioned phonology (Sande Reference Sande2019a, Sande et al. Reference Sande, Jenks and Inkelas2020). Work in progress (Jenks Reference Jenks2018, Baron Reference Baron2019) also shows that Cophonologies by Phase can account for syntax–prosody interaction without requiring a separate step of syntax-to-prosody mapping in the grammar.

I show that CBP can straightforwardly model a range of phonological processes that require at least two morphological triggers. As with phonology across words or in sub-word domains (Sande Reference Sande2019a, Sande et al. Reference Sande, Jenks and Inkelas2020), the domain of morphologically conditioned phonology with two triggers appears to be related to syntactic phase boundaries.

§2.1 and §2.2 present doubly morphologically conditioned phonological alternations in two languages, showing that Cophonologies by Phase (Sande & Jenks Reference Sande and Jenks2018, Sande Reference Sande2019a) straightforwardly accounts for doubly conditioned phonology, while making clear predictions about the locality restrictions and scope of such processes. The locality predictions are borne out across languages, as shown in §3. In §4, doubly conditioned phonology is shown to be difficult to account for in alternative frameworks.

2 Doubly conditioned phonology in Cophonologies by Phase

2.1 Sacapultec Mayan vowel lengthening

This section describes a doubly conditioned alternation of vowel quantity in Sacapultec, based on data from DuBois (Reference DuBois1981, Reference DuBois1985). Sacapultec (also known as Sakapultek and Sacapulteco) is a Mayan language spoken by about 7000 speakers in Guatemala (Lewis et al. Reference Lewis, Simons and Fennig2014).

2.1.1 Sacapultec data

In Sacapultec, some but not all, nouns undergo vowel lengthening when a possessive marker is present. Lengthening fails to occur in the presence of other affixes, and in a subset of lexical items. Both an alternating noun and a possessive suffix must be present in the relevant domain for lengthening to apply. Thus two non-phonological triggers are required in order for lengthening to surface. A similar process applies in other Mayan languages, as described by Bennett (Reference Bennett2016).

Nouns in Sacapultec can be preceded by a possessive prefix: e.g. /ʧaːk/ ‘work’, /ni-ʧaːk/ ‘my work’. For the 1st person singular, the possessive prefix has two allomorphs, /ni-/, which occurs before consonants, and /w-/, which occurs before vowels.

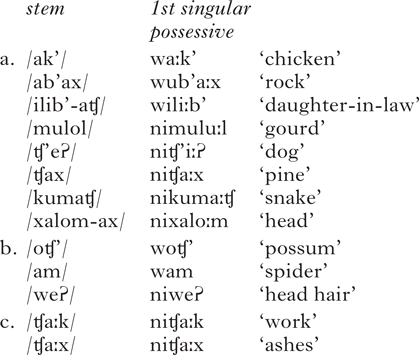

A subset of lexical items shows final vowel lengthening only in the context of a possessive prefix.Footnote 2 The data in (1a) shows a set of nouns that exhibit final vowel lengthening when preceded by a 1st person singular possessive prefix. The forms in (b) show that not all roots are susceptible. Vowel length is contrastive in Sacapultec, and underlying long vowels remain long in possessive forms. (All data is from Dubois Reference DuBois1981: 184–189.)

-

(1)

/ʧax/ ‘pine’ and /ʧaːx/ ‘ashes’ in (1a) and (c) form a minimal pair, distinguished in their bare forms only by vowel length. After a possessive prefix, they neutralise, both surfacing with a long vowel. Inalienable nouns like /xalom/ ‘head’ in (1a) are normally possessed, and in their non-possessed form must take a suffix, /-ax/.

Whether a word falls into the alternating or the non-alternating class does not seem to be predictable on the basis of phonotactics. We see vowel-initial and consonant-initial roots that lengthen, and those that do not, and the same sets of final consonants and final vowels are found in both classes of nouns. It cannot be the case that alternating roots have an underlying long vowel which shortens in the bare form, because there are roots which maintain a long vowel in both environments (1c). DuBois does not explicitly discuss the number of lexical items that fall into the lengthening and non-lengthening classes, but provides more examples of the alternating than the non-alternating type.

Any form that exhibits lengthening in 1st person singular contexts also exhibits lengthening in all possessive contexts, e.g. /tiɁb'al/ ‘stinger’, /ri-tiɁb'aːl/ ‘its stinger’. The possessive paradigm is given in (2).

-

(2)

Almost all possessive prefixes have the same form as transitive subject prefixes on verbs (except 1st singular, which surfaces as [in-, inw-] in transitive subject contexts), but they only trigger lengthening when they serve as possessives.

We have seen that final vowel lengthening in Sacapultec is lexically specific. It is also specific to the possessive prefix, and not to other affixes. The stative predicate prefix, the only other nominal prefix described by DuBois, does not trigger lengthening, as shown in (3).

-

(3)

Sacapultec also has nominal suffixes, for example the plural, which always surfaces with a long vowel in the final syllable, no matter which lexical root is present, or whether the noun is possessed: /ak'aːl/ ‘child’, /ak'al-aːb’/ ‘children’; /b'o:jeʃ/ ‘ox’, /b'o:jiʃ-aːb’/ ‘oxen’.

In sum, Sacapultec has a final vowel lengthening alternation which applies only when both a lexical item of the alternating class and a possessive prefix are present.

2.1.2 A Cophonologies by Phase analysis of Sacapultec lengthening

This section presents an analysis of Sacapultec doubly conditioned final vowel lengthening. Numerous frameworks have been proposed to model morphologically conditioned phonology: Exception features (Chomsky & Halle Reference Chomsky and Halle1968, Lightner Reference Lightner and Worth1972), Lexical Morphology and Phonology (Kiparsky Reference Kiparsky, van der Hulst and S. H. Smith1982, Reference Kiparsky, Elert, Johansson and Strangert1984), Cophonology Theory (Orgun Reference Orgun1996, Inkelas et al. Reference Inkelas, Orhan Orgun, Zoll and Roca1997, Inkelas & Zoll Reference Inkelas and Zoll2005, Reference Inkelas and Zoll2007), Indexed Constraint Theory (Itô & Mester Reference Itô, Mester and Goldsmith1995, Reference Itô, Mester, Kager, van der Hulst and Zonneveld1999, Pater Reference Pater, Bateman, O'Keefe, Reilly and Werle2007, Reference Pater and Parker2009), Stratal OT (Bermúdez-Otero Reference Bermúdez-Otero1999, Reference Bermúdez-Otero and Trommer2012, Kiparsky Reference Kiparsky2000, Reference Kiparsky, Vaux and Nevins2008) and Emergent Phonology (Archangeli & Pulleyblank Reference Archangeli, Pulleyblank, Lee, Kang, Kim, Kim, Kim, Rhee, Kim, Kim, Lee, Kang and Ahn2012, Reference Archangeli, Pulleyblank, Siddiqi and Harley2016, McPherson Reference McPherson2019). However, these approaches have not been used to model phonological alternations that apply only when two (or more) morphological triggers are present, and many are in fact incapable of doing so. Here I show that a CBP analysis (Sande & Jenks Reference Sande and Jenks2018, Sande Reference Sande2019a, Sande et al. Reference Sande, Jenks and Inkelas2020) not only easily models such patterns, but also predicts that such interactions should exist. Alternative analyses are considered in §4.

CBP combines Distributed Morphology operations such as late insertion of vocabulary items (Halle & Marantz Reference Halle, Marantz, Hale and Keyser1993) with phonological evaluation via weighted constraints (Goldsmith Reference Goldsmith1990, Reference Goldsmith and Goldsmith1993, Legendre et al. Reference Legendre, Miyata and Smolensky1990). Crucially, it proposes an enriched notion of vocabulary items (lexical representations).

Vocabulary items in traditional Distributed Morphology map bundles of morphosyntactic features to phonological forms, as in (4) (Embick & Noyer Reference Embick, Noyer, Ramchand and Reiss2007: 298–299).

-

(4)

In CBP, the phonological form associated with each vocabulary item is more than just a string of segments. Vocabulary items contain up to three components: (i) an underlying phonological representation ℱ, (ii) a prosodic subcategorisation frame ℘ and (iii) a constraint-weight readjustment ℛ. This last addition, morpheme-specific constraint-weight readjustment, is the crucial innovation of CBP that is taken advantage of here to account for doubly conditioned phonological effects. Note that even though one of the conditioning factors is the presence of a particular functional morpheme, and another the presence of a particular lexical item, these two conditioning types are handled uniformly in CBP, as constraint reweightings specific to vocabulary items.

Morpheme-specific constraint-weight adjustments add to the default weight of constraints for a given language, and the adjusted weighted constraint grammar applies to the spell-out domain, specifically the syntactic phase, containing that morpheme. Later phases are unaffected by the morpheme-specific constraint weights of material introduced inside earlier phase domains. Morpheme-specific weights only apply during phonological evaluation of the phase containing the triggering morpheme. Phase-based spell-out predicts that morpheme-specific phonology should be coextensive with phase domains, which can be smaller or larger than a single prosodic word. These predictions are shown in Sande (Reference Sande2019a) and Sande et al. (Reference Sande, Jenks and Inkelas2020) to be motivated by sub-word and cross-word morphologically conditioned phonology.

The two constraints relevant for accounting for vowel lengthening in Sacapultec are given in (5).

-

(5)

FinalLength refers to prosodic word edges. Note that prosodic words are still assumed to be part of the phonology in CBP, despite not determining the domain of phonological evaluation. Phonological constraints can refer to prosodic edges, and prosodic structure is built and revised at each instance of spell-out, as laid out in Sande et al. (Reference Sande, Jenks and Inkelas2020).

In the default grammar of Sacapultec, Dep has a weight of 12 and FinalLength a weight of 0.5. Throughout, weights in the default and doubly conditioned grammars are determined using the MaxEnt Grammar Tool (Hayes et al. Reference Hayes, Wilson and George2009), with weights rounded up to the nearest 0.5.

The basic structure of a possessive noun phrase in Sacapultec, exemplified by the root /ak’/ ‘chicken’, is shown in (6).

-

(6)

The tree in (6) is adapted from Coon (Reference Coon2017), where the possessor DP is in the specifier position of n, analogous to transitive subjects in the specifier position of v. I assume that all possessive nouns and pronouns are introduced in the lower DP slot, dominated by a PossP. The noun root moves to n, where it enters into an agreement relationship with the possessor (again analogous to agreement in transitive vPs) (Coon Reference Coon2017). The Poss head itself, rather than the person features associated with the possessive DP, triggers the lengthening phenomenon, since the same set of person markers in transitive subject contexts is not associated with lengthening. This allows transitive and possessive agreement prefixes to be treated uniformly, as a single set of vocabulary items. Nominal roots are the complement to a nominalising head n (Halle & Marantz Reference Halle and Marantz1994). There are different n heads for different classes of nouns (Ferrari Reference Ferrari2005, Lowenstamm Reference Lowenstamm, Hartmann, Hegedüs and van Riemsdijk2008, Acquaviva Reference Acquaviva2009, Kramer Reference Kramer2015). The class of alternating nouns is associated with a particular n head, which introduces the possibility of lengthening.

I take Ds to be phase heads in Sacapultec, as commonly assumed across languages (cf. Chomsky Reference Chomsky and Kenstowicz2001, Marvin Reference Marvin2002). Phase heads are assumed to be spelled out together with their complements, to the exclusion of the specifier (Chomsky Reference Chomsky and Kenstowicz2001). The DP within the PossP will be spelled out initially on its own, and then again upon spell-out of the higher DP domain, which contains both the Poss head and the n head.

I propose the set of vocabulary items in (7).

-

(7)

There are two 1st person singular possessive insertion rules, both inserted in the context of [1sg, poss] features in the morphosyntax. The phonological feature content of (7a) is /w/, inserted only when it can be prefixed to a prosodic word which begins with a vowel, as specified by the prosodic subcategorisation frame ℘. For the second, the feature content is /ni/, inserted before a consonant-initial word. Both are associated with morpheme-specific weights, where the weight of FinalLength is increased and that of Dep decreased when one of these morphemes is present in the spell-out domain.Footnote 4

The possessive prefixes are associated with constraint reweighting, but on its own the possessive reweighting will not trigger lengthening; the weight of Dep (12 ― 3 = 9) still overpowers that of FinalLength (0.5 + 5 = 5.5).

Alternating roots like /ak’/ are associated with an alternating n head, as in (7c), which is also specified for constraint reweighting. The weight of the faithfulness constraint Dep is decreased by 6 (12 ― 6 = 6), and the weight of FinalLength is slightly boosted (0.5 + 2.5 = 3). Non-alternating n in (7d) is not associated with a constraint-weight readjustment.

When either the possessive prefix or alternating n is present without the other, the reweighting will not be enough to motivate final lengthening. However, when both are present in the same phase domain, the weight of FinalLength is increased from 0.5 to 8, and that of Dep decreased from 12 to 3, as in Table I, resulting in a strength reversal. Only in these cumulative reweighting domains is the final lengthening candidate preferred.

Table I Doubly conditioned weights in Sacapultec.

When a possessive prefix is present with a non-alternating root such as /am/ ‘spider’, the adjusted weight of FinalLength is not enough to overpower the faithfulness constraint Dep, as shown in (8) (Dep = 9; FinalLength = 5.5).

-

(8)

This is a Maximum Entropy Harmonic Grammar tableau (Goldwater & Johnson Reference Goldwater, Johnson, Spenader, Eriksson and Dahl2003), where candidates are evaluated based on their harmony scores (Legendre et al. Reference Legendre, Miyata and Smolensky1990, Smolensky & Legendre Reference Smolensky and Legendre2006), and the output is a probability distribution over possible candidates. Harmony is calculated by multiplying the number of violations of a given constraint by its weight, and summing across the tableau. The candidate with the lowest harmony score is the most likely to surface. Predicted and observed surface probabilities are presented in the tableaux for comparison of fit. In this case, the faithful candidate has the lowest harmony score and is predicted to surface almost categorically.

When an alternating root is present, but a possessive prefix is not, the adjusted weight of Dep is not low enough to be overpowered by FinalLength, as in (9) (Dep = 6; FinalLength = 3), where we see a stative prefix rather than a possessive prefix.

-

(9)

Only in the presence of both an alternating root and a possessive D head do we see vowel lengthening, as in (10) (Dep: 12 ― 3 ― 6 = 3; Final Length: 0.5 + 5 + 2.5 = 8).

-

(10)

When neither is present, as in the case of a stative prefix with a non-alternating root in (11), the default grammar applies.

-

(11)

In each of the tableaux above, I assume that there are regular constraints on prosodic structures in the language which simplify the recursive prosodic word structure in the input to a single prosodic word in the output. Because prosody is not the focus of this paper, I do not discuss these prosodic constraints here.

The distribution of final vowel lengthening is summarised in Table II.

Table II Distribution of Sacapultec final vowel lengthening.

We achieve a successful model of double morphological conditioning only in the environment of both an alternating root and possessive prefix by associating a morpheme-specific constraint-weight adjustment with both triggers. Neither trigger on its own is powerful enough to affect the preferred output. Only when both are present is the weighted constraint grammar readjusted so that the lengthening candidate categorically surfaces.

2.2 Guébie vowel harmony

A second example of a doubly conditioned phonological phenomenon comes from Guébie, a Kru language spoken in seven villages in the prefecture of Gagnoa in the Ivory Coast. Guébie full vowel harmony, like Sacapultec lengthening, only surfaces in the presence of two phonology-external triggers: a lexical root of the alternating class and either a 3rd person object enclitic (on verbs) or a plural suffix (on nouns). Harmony fails to apply if either of the triggers is absent. I focus on the verbal context here (the nominal facts mirror the verbal ones). This case study shows that one crucial prediction of CBP is borne out; specifically, the domain of a doubly conditioned alternation can be smaller than a word boundary, if it is coextensive with a phase domain.

The data presented here comes from work with the Guébie community between 2013 and 2019. The vowel-harmony process was originally described by Sande (Reference Sande2017). Some background on Guébie phonology is presented in §2.2.1, the harmony facts are presented in §2.2.2 and a CBP analysis is given in §2.2.3.

2.2.1 Guébie phonology: background

Guébie is a tonal language, with four distinct underlying tone heights, here labelled with superscript numerals 1–4, where 4 is high. There are five distinct heights on the surface, 1–5, where 5 is super-high and only surfaces in imperfective contexts (Sande Reference Sande2017, Reference Sande2018). Guébie has ten contrastive vowels: [+ATR] /i e u o ə/ and [―ATR] /ɪ ɛ ʊ ɔ a/. Neither nasality nor length is contrastive on vowels.Footnote 5 Vowels within a word show ATR harmony, determined by the quality of the root vowels. ATR harmony is not the topic of this section – there are multiple harmony processes in Guébie – but it is useful to summarise the ATR harmony pattern before proceeding. Vowels in prefixes and suffixes match the ATR quality of root vowels. Both [+ATR] and [―ATR] seem to be active, and affect prefix vowels to the left as well as suffix vowels to the right. In other words, both [+ATR] and [―ATR] are ‘dominant’, and the harmony process is bidirectional.

The example in (12a) shows a particle verb construction where the verb is fronted in the absence of an auxiliary, leaving the particle to surface as an independent word clause-finally. In this case, the final particle [joku] has [+ATR] vowels, the underlying value for this particular particle. In (12b), the same particle verb surfaces in a different clause type. There is an auxiliary present, which prevents the verb from fronting, so the verb and particle surface together, clause-finally within a single word. In this construction only, the particle verb surfaces as a prefix on the verb, and regressive vowel harmony applies. The verb root in (12) contains [―ATR] vowels, and in (12b) the particle also surfaces with [―ATR] vowels.Footnote 6

-

(12)

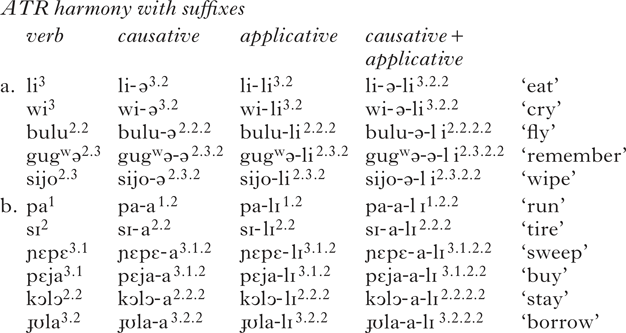

We also see suffixes showing ATR alternations dependent on the vowel quality of verb roots, as in (13). The applicative suffix surfaces as [li] in [+ATR] contexts, and as [lɪ] in [―ATR] contexts, and the causative suffix surfaces as [ə] in [+ATR] contexts and [a] in [―ATR] contexts. Unlike regressive harmony in particle verb ATR alternations, suffix ATR alternations are progressive.

-

(13)

This harmony process applies in all word categories, but there are a few outer suffixes (the definite marker on nouns and all three nominalising suffixes on verbs) which do not undergo ATR harmony. One of the nominalisers is /-li/, which surfaces with a [+ATR] vowel even when following a [―ATR] root: [ɟʊlali3.2.2], *[ɟʊlalɪ3.2.2] ‘borrowing’. Sande (Reference Sande2019a) analyses the domain of ATR harmony as constrained by a phase boundary separating inner affixes (harmony undergoers) from outer ones (non-alternating). The phase-based analysis of ATR harmony adopted by Sande extends to full vowel harmony, and is presented in §2.2.3.

2.2.2 Guébie full vowel harmony facts

As in Sacapultec, there is a phonological process in Guébie which applies only (i) in the environment of a subset of affixes (3rd person object markers), and (ii) in a subset of lexical items. An example of full harmony is shown in the verb root vowels in (14a) and (b), where in the latter, the root vowels match all features of the 3rd person singular enclitic vowel.

-

(14)

Vowel hiatus across a morpheme boundary is regularly resolved via deletion of the first vowel in the sequence in Guébie, unless that vowel is the only exponent of some morpheme: /bala3.3==ɔ2/ → [bɔlɔ3.2], *[bɔlɔɔ3.3.2]. Because the final root vowel is deleted before the enclitic, we cannot determine whether harmony applies to monosyllabic verb roots: /li3=ɔ2/ → [lɔ32]. There is simply no root vowel produced in such contexts. For this reason, I only consider polysyllabic roots.

There are non-alternating roots such as /ɟʊla3.2=ɔ2/ → [ɟʊlɔ3.2] ‘take him/her’, in which we see an object enclitic vowel added at the end of the word. The final vowel of the root fails to surface, due to regular vowel-hiatus resolution. For non-alternating roots like /ɟʊla3.2/, when other suffixes intervene between the root and object enclitic, the object enclitic surfaces immediately after the preceding suffix vowel: /ɟʊla3.2-a2=ɔ2/ (take-caus=3sg.acc) → [ɟʊlaɔ3.2.2] ‘cause him/her to take’. Here, the final root vowel is deleted before the causative suffix /-a/, but the causative suffix is not deleted before the object enclitic, presumably to avoid deleting the only exponent of the causative morpheme. Given these facts, I analyse object enclitics as concatenative, rather than as realised by a non-concatenative root-vowel changing process.

All 3rd person object-marking enclitics, human and non-human, trigger full vowel harmony. The inventory of object markers is provided in Table III.

Table III Guébie object markers.

Three verbs are shown in (15), each with three different 3rd person object enclitic markers, all of which trigger harmony.

-

(15)

Non-3rd person object markers do not trigger harmony, as shown in (16).

-

(16)

Not all verbs undergo harmony, as shown in (17). In a corpus of 1839 disyllabic roots, 617 are subject to full vowel harmony (only about 33.5%).Footnote 7 The subset of roots affected by full vowel harmony does not form a semantic or phonological natural class (Sande Reference Sande2017, Reference Sande2019b).

-

(17)

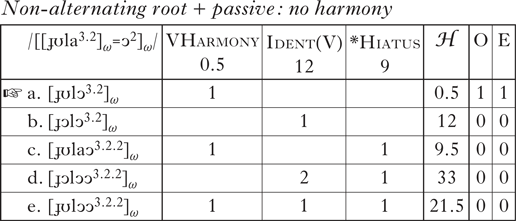

Other phonologically identical affixes fail to trigger full harmony. Recall that the shape of the 3rd person singular human object enclitic is /ɔ2/. The passive suffix, which is phonologically identical, does not trigger harmony, even on alternating roots, as in (18).

-

(18)

As with ATR harmony, discussed in §2.2.1, outer affixes such as the nominalisers in (19) fail to undergo harmony.

-

(19)

Note that the data in (19) could be analysed as due to leftward spreading of features from the object marker to the root. While we see regressive harmony in object enclitic contexts, there are other environments in the language where progressive harmony is found (recall the root-controlled ATR harmony described in §2.2.1). Alternatively, the data could be analysed as being determined by the hierarchical structure of the word, where only morphemes that attach before the object marker are affected. The analysis in §2.2.3 straightforwardly accounts for the facts as due to a phase boundary between the object enclitic and nominaliser. In this way, hierarchical structure and phase boundaries account for the domain of harmony in both the verbal and nominal domains. Additionally, the same syntactic phase domain is relevant for both ATR harmony (§2.2.1) and full harmony.

Affixes can intervene between the object enclitic and verb root. In this case, different speakers have different strategies. For some speakers, harmony is blocked by intervening affixes, as in (20b, d), and for others, harmony applies across the entire domain, as in (20c, e). The % symbol in (20) indicates that some, but not all speakers, produce and accept the form in question.

-

(20)

When a non-alternating root is present, affixes never show full vowel harmony: /ɟʊla3.2-a2=ɔ2/ → [ɟʊlaɔ3.2.2], *[ɟʊlɔɔ3.2.2] ‘cause him/her to take’. Of the six speakers from whom relevant data was collected, four preferred (20b) to (20c).Footnote 8

2.2.3 A Cophonologies by Phase analysis of Guébie harmony

Full vowel harmony surfaces only in the environment of particular affixes and roots that cannot be characterised entirely by their phonological or syntactico-semantic features. Harmony applies only to morphemes within a single phase, not to outer morphemes such as nominalisers on verbs or definite markers on nouns. The CBP analysis presented here accounts for both the double conditioning and the locality effects. I follow earlier work (Sande Reference Sande2019a: 477) in assuming that object enclitics and verb roots are introduced within the same Voice phase.

The phonological constraints in (21) relevant for motivating the full harmony process in Guébie include a faithfulness constraint Ident(V)-IO and a vowel-harmony constraint, VHarmony. Many harmony frameworks are compatible with CBP; I refrain from adopting a specific one here. *Hiatus prevents the root-final vowel from surfacing when immediately preceding a vowel-initial suffix or enclitic.

-

(21)

Ident(V) is more strongly weighted than VHarmony in the default grammar (12 vs. 0.5), resulting in faithful outputs in the majority of contexts. *Hiatus retains its high weight, 9, across all grammatical contexts.

Recall that full vowel harmony on roots occurs in the presence of object enclitics, but not other suffixes. I propose that object markers are differentiated from other affixes by their association with a constraint reweighting. While it may seem coincidental that all 3rd person object markers are associated with the same morpheme-specific constraint readjustment, a learner of Guébie must come to associate the full vowel-harmony alternation with exactly this set of contexts, and not others. In the presence of these morphemes only, a reweighted cophonology applies.

The vocabulary item for the 3rd person human singular object marker is given in (22). All 3rd person object markers are assumed to be associated with the reweighting in ℛ.

-

(22)

The weights in (22) are added to those in the default grammar, giving VHarmony = 6 (0.5 + 5.5) and Ident(V) = 9 (12 ― 3). Ident(V) still outweighs VHarmony, so the faithful output will be the preferred or most common output, as in the default. On their own, these weights are not enough to result in harmony, as Ident(V) is still highly weighted.

Alternating roots are selected by a v head that is also associated with constraint reweighting, as in (23).

-

(23)

Instead of each root being indexed as either alternating or non-alternating, it is associated with an alternating v head, as in (23), or a non-alternating v head whose ℛ specification is null. In the latter case, neither the non-alternating root nor the dominating v is associated with any reweighting, so that the default weights will apply and no alternation is found.

On their own, the weights in (23) combine with the default grammar to give VHarmony = 3 (0.5 + 2.5) and Ident(V) = 6 (12 ― 6). Again, this is not enough to result in full harmony, since the harmony constraint is still outweighed by a faithfulness constraint. However, when both a morphosyntactic harmony trigger and an alternating root are present in the same spell-out domain, the default weights are modified according to both reweightings, and the cumulative effects are enough to result in harmony, as in Table IV.

Table IV Cumulative effects of morpheme-specific cophonologies in Guébie.

Tableaux showing the phonological constraint interactions in each of the above four environments are given in (24)–(27). When both an alternating root and an object enclitic are present, the relevant weights are as in (24) (VHarmony = 8.5, Ident(V) = 3), and full vowel harmony applies throughout the word.

-

(24)

When an alternating root is present, but an object marker is not, harmony does not apply. A domain containing an alternating root plus any other suffix, for example the passive, is subject to the alternating root reweighting in (23). However, the reweighting in (23) does not adjust the default grammar weights enough to have an observable effect, as shown in (25).

-

(25)

When an alternating root is present along with a non-trigger affix, the harmony candidate is predicted to surface 97% of the time.

When an object enclitic is present with a non-alternating root, a non-harmony candidate is predicted to surface 95% of the time, as in (26). Here, the domain containing a non-alternating root and triggering morpheme is subject to the reweighting of (22), but not that of (23), resulting in the faithful candidate surfacing in the vast majority of cases.

-

(26)

When neither trigger is present – when neither an alternating root nor an object marker is part of the spell-out domain – the default grammar applies, categorically resulting in no harmony, as in (27).

-

(27)

The combined effect of two reweightings results in full vowel harmony only when both an object enclitic and an alternating root are present. The analysis proposed here assumes that the 600+ alternating roots are alternating because they are associated with a different v head than non-alternating roots. This analysis predicts that we may also find these two classes of roots patterning differently elsewhere in the grammar. This prediction is borne out: the same subset of roots that undergoes harmony also allows for optional deletion of the root-initial vowel, i.e. CVCV → CCV (Sande Reference Sande2017, Reference Sande2019a). Roots that fail to show harmony never surface as CCV.

A benefit of using an inherently phase-bounded model of phonological evaluation is that it straightforwardly accounts for the locality restrictions on harmony effects. Recall that nominalising morphemes on verbs are never subject to harmony. Nominalisers fall outside of the Voice phase domain in which harmony is conditioned; there is independent language-specific evidence for this domain boundary, both from syntax and from other morphophonological processes (Sande Reference Sande2017, Reference Sande2019a). By the time nominalisers are inserted, the phase containing verbs and object enclitics (VoiceP in Sande Reference Sande2019a) has already been spelled out, and the morpheme-specific requirements of verbs and objects no longer apply, as in (28).

-

(28)

In (28), the input includes the previously spelled-out [bɔlɔ3.2] from (24), as well as the nominalising morpheme, which has newly been introduced in the higher phase domain. By re-evaluating previously spelled out material at later phase domains, together with new content, CBP can account for cyclic phonological effects (Sande et al. Reference Sande, Jenks and Inkelas2020).

3 Other cases of doubly conditioned phonology

In this section I briefly describe five additional cases of phonological alternations with two (or more) non-phonological triggers. Each dataset comes from a different language and language family. The diversity of languages represented here suggests that morphologically conditioned phonology with two triggers is a widespread phenomenon.

The data presented throughout this section shows that the predictive power of CBP is warranted. The Amuzgo data in §3.1 shows that a doubly conditioned tone alternation applies unless a phase boundary intervenes. Donno So in §3.2 shows that morphemes introduced in different words can co-trigger phonological alternations, as long as they are introduced within the same phase boundary. The Donno So case study also shows that co-triggers can affect multiple words, roots, affixes and closed classes of morphemes such as numerals. The Ende case study in §3.3 shows that more than two triggers can interact within a phase to determine a surface form. Together with case studies from Siouan and Amahuaca, this data shows that a range of types of alternations can be doubly morphologically conditioned: tonal overlays, reduplication, truncation and ablaut.

3.1 Amuzgo

In San Pedros Amuzgo (Otomanguean), spoken in Oaxaca, Mexico, there are eight lexically contrastive tones, 5, 3, 34, 1, 12, 53, 31 and 35, where 5 is high (Smith Stark & Tapia García Reference Smith Stark and García1984). The default tone of a verb is overridden in 1st and 2nd person contexts, and the overriding patterns are distinct for different lexical classes. When a causative morpheme intervenes between the verb root and the subject, these tonal overlays fail to surface. The data presented in this section was documented by speaker Fermín Tapia García, and are analysed in Kim (Reference Kim, Panacar and Léonard2016, Reference Kim2019).

Most Amuzgo verb stems are monosyllabic, and inflect for person and number via mutations in glottalisation, vowel height and tone. This section focuses on tonal mutations. Kim (Reference Kim, Panacar and Léonard2016) analyses the tone that surfaces in 3rd person singular contexts as being the default tone of the verb. Lexical classes, labelled as A–O by Kim (Reference Kim, Panacar and Léonard2016), are made up of verbs that surface with the same tone melodies in the 1st, 2nd and 3rd singular. The 1st and 2nd singular tones are not predictable based solely on the 3rd singular tone of the verb, as shown in (29).

-

(29)

Kim (Reference Kim, Panacar and Léonard2016) argues that the tone melody that surfaces in the 3rd singular is the default melody for each root, because, among other things, ‘only five of the eight tones – /53/, /31/, /12/, /1/, and /3/ – are found in the 1sg and 2sg, whereas all eight are attested in 3sg forms’ (Reference Kim, Panacar and Léonard2016: 207).

The underlying tone, which surfaces in the 3rd singular, is overridden in the 1st and 2nd singular. Underlying tone is not enough to predict the surface tone in the 1st and 2nd singular (cf. (29)); one needs to know which lexical class the verb belongs to. Only when both a certain class of lexical items and a certain set of morphological features are present do we see a particular alternation. Kim (Reference Kim, Panacar and Léonard2016, Reference Kim2019) analyses this pattern with cophonologies sensitive to lexical class and person features; in other words, as morphologically conditioned phonology with two triggers. The surface tone of all verbs is doubly conditioned by (i) lexical class and (ii) person features of the subject.

Upon causativisation, tones become predictable based on their underlying (3rd singular) tones. For example, the doubly conditioned tones for the class C verb ‘run’ are provided in (30a) (Kim Reference Kim, Panacar and Léonard2016: 215). When the causative morpheme is added, as in (b), person no longer has a surface effect, and the underlying tone of the verb surfaces across the board.

-

(30)

A class C verb like ‘run’ with a 1st singular subject results in a 53 pattern on the verb, and C plus 2nd singular results in 12. However, it is not the case that 1st singular always results in a 53 overlay or 2nd singular in a 12 overlay. In CBP, both a class C verbalising head v and a 2nd singular morpheme would be associated with morpheme-specific constraint-weight readjustments that prevent alternative melodies (contour tones and level 5 tones, for example, the latter of which is never permitted in the 1st or 2nd singular) and boost the likelihood of 12. Only when both relevant ℛs are present in the same phase domain are the constraint weights adjusted enough for 12 to surface.Footnote 9

Kim & Sande (Reference Kim and Sande2019) analyse the causative Voice head in Amuzgo as introducing a phase boundary, as in (31). In causative clauses only, lexical class features of the root (introduced on the categorising v head), and subject person features, introduced higher in the structure, are separated by a phase boundary, Voicecaus.Footnote 10

-

(31)

Person features are introduced higher in the structure than lexical class features, and the two are not structurally (and in many cases linearly) adjacent. Thus it cannot be an adjacency requirement that allows two elements to co-trigger a process; instead, it has to do with the syntactic domain in which they are introduced.

Doubly conditioned tonal overlays in Amuzgo disappear in the presence of an intervening causative Voice head, supporting a phase-based analysis of the domain of double conditioning.

3.2 Donno So

Donno So, a Dogon language spoken in Mali, has two contrastive tone heights, H and L. As in many Dogon languages, certain elements within a noun phrase trigger tonal overlays on the noun (or on the noun plus additional structure) (McPherson Reference McPherson2014, Heath Reference Heath2015). Typically across Dogon, when there is more than one trigger or overlay-controlling element within the noun phrase, there is a competition for dominance, and the trigger associated with the highest-ranked constraint (in McPherson's and Heath's approach) determines the surface tone pattern (see Sande et al. Reference Sande, Jenks and Inkelas2020 for an analysis of these cross-word dominance patterns in Dogon in CBP). In Donno So, when certain pairs of elements co-occur in a noun phrase, they co-trigger a particular tonal overlay that is not present when only one of the triggers surfaces (Heath Reference Heath2015).

In Donno So, the order of elements within a noun phrase is either [Poss N Num Adj Dem/Def Quant] or [Poss N Adj Num Dem/Def Quant]. Adjectives assign a L tone melody to the noun on their left, as in (32a). When N, Num and Adj are all present, the L tone assigned by Adj applies to the sequence [N Num Adj]L or [N Adj Num]L, such that the trigger (Adj) is affected along with the noun and numeral. This kind of self-docking, discussed further by McPherson (Reference McPherson2014) and Heath (Reference Heath2015), shows the trigger adjective being affected along with the rest of the domain, an option predicted by CBP.

-

(32)

When a definite marker is present in a noun phrase to the exclusion of a numeral, the definite marker has no tonal effect (33a). When a numeral is present without a definite marker, the numeral has no tonal effect (33b). However, when both a definite marker and numeral are present, a LH tone melody is assigned to the [N (Adj) Num (Adj)]LH complex, as in (33c).Footnote 11 Note that the tone of the numeral trigger is affected, as well as the tone of surrounding words within the same DP phase domain (noun and adjective).

-

(33)

Here we see that morphologically conditioned phonology with two triggers can affect multiple words, including nouns. Structurally higher morphemes, such as quantifiers which surface to the right of demonstratives, and possessors, which surface to the left of nouns, are unaffected: Poss [N Adj Num]LH=def (Heath Reference Heath2015: 242). I propose, following McPherson & Heath (Reference McPherson and Heath2016) on the structure of Dogon noun phrases, that alienable possessors and quantifiers are introduced higher in the structure than the definite marker D, and that D is a phase head. Triggers introduced within the same phase domain, including non-linearly adjacent triggers like Num and Def, are associated with morpheme-specific constraint weights that boost a LH tonal overlay constraint, such that there is a surface effect only for elements within the DP phase, only when both the Num and Def triggers are present.

3.3 Ende

In Ende (Malayo-Polynesian; Papua New Guinea), verbs have two different stem forms, infinitival and inflectional (Lindsey Reference Lindsey2019). For a subset of roots, the infinitival forms show reduplication. While these are mostly monosyllabic roots, as in (34a), Lindsey shows that prosody and phonotactics alone cannot distinguish reduplicating roots from non-alternating roots. About 25% of infinitival forms are reduplicated.

-

(34)

The Ende facts become more complicated when we consider forms in which affixes are added to the infinitival stem. When root-level affixes (described as such by Lindsey) like pluractional and applicative are added, reduplication is blocked: [po-ŋg], *[popo-ŋg] ‘sharpen-appl’. When stem-level affixes such as derivation and case are added, reduplication is not blocked. When both types of affix are present, reduplication is blocked, showing that any time a root-level affix is present, reduplication is prevented from surfacing.

Reduplication only appears when both an alternating root and infinitival morpheme are present; however, affixes linearly and hierarchically nearest to the root can block reduplication. In CBP, the cumulative effects of root-specific and infinitival-specific cophonologies can derive reduplication in the same way as other cases of morphologically conditioned phonology with two triggers. Blocking of reduplication in the presence of root-level affixes can be modelled in CBP by associating a blocking cophonology with derivational affixes introduced in the same phase as the root and infinitival morpheme, subtracting weight from the relevant constraint. The morpheme-specific constraint weights of the blocking affixes cancel out the cumulative effects of the root and infinitival morpheme. When there is no root-level affix, reduplication applies, due to the cumulative morpheme-specific properties of the root and infinitival morpheme.

3.4 Siouan

Across Siouan languages, the quality of vowels in some roots changes in the presence of a subset of affixes. This phenomenon has been described as morphologically conditioned ablaut in a number of individual Siouan languages, including Crow (Graczyk Reference Graczyk2007), Lakota (Rankin Reference Rankin1995, Albright Reference Albright2002) and Hidatsa (Jones Reference Jones1992). It has also been described in comparative and historical contexts as a cross-Siouan process (Rankin Reference Rankin1995). Representative data from Lakota (from Rankin Reference Rankin1995) is provided in (35), where the verbs /ˈkaɣa/ and /ˈja/ undergo ablaut (/a/ → [e]) in the presence of negative, adverbial and ‘as if’ suffixes, but not in other contexts. The verb /kaˈla/, on the other hand, never undergoes ablaut.

-

(35)

There are also /-e/-final stems which do not alternate, and have final [-e] in all positions, showing that the difference between /kaˈla/ and /ˈja/ cannot boil down only to a difference between underlying root-final /a/ and /e/: [waʃte, waʃte-pi] ‘be good’ (invariant [e]) vs. [ʧʰepe, ʧʰepa-pi] ‘be fat’ (alternating [a]/[e]) (Albright Reference Albright2002).

Just as for Guébie and Sacapultec, CBP can easily account for the doubly conditioned ablaut in Siouan with a set of morpheme-specific constraint reweightings promoting ablaut associated with triggering affixes like the negative in Lakota, and a set of morpheme-specific faithfulness demotion weights associated with undergoing roots. Only when both are present will an ablaut candidate be preferred.

3.5 Amahuaca

Amahuaca, a Panoan language spoken in the Peruvian Amazon, shows morphologically and lexically conditioned truncation (Clem Reference Clem2019: 13). Amahuaca has a three-way case system. One set of trisyllabic roots surfaces faithfully as trisyllabic when followed by a concatenative case-marking suffix in ergative and nominative contexts. In accusative contexts, however, they are truncated to two syllables (36a). Other trisyllabic roots, and roots of other shapes, do not undergo truncation (36b). The root-final syllable in non-accusative contexts is not predictable from the form or semantics of the accusative form, thus an analysis of truncation in accusative contexts rather than insertion or allomorphy in non-accusative contexts is adopted (see Clem Reference Clem2019: 12–13 for further discussion).

-

(36)

The related Panoan languages Yaminahua and Nahua show the same doubly conditioned truncation pattern (Kelsey Neely, personal communication).

The CBP analysis presented for Sacapultec and Guébie can be straightforwardly extended to account for the Panoan facts, where only in the environment of both an accusative morpheme and undergoing root will the constraints be weighted such that a truncation candidate surfaces.

3.6 Cross-linguistic summary

We have seen that a wide range of types of phonological alternations can require more than one morphological (non-phonological) trigger, as summarised in (37).

-

(37)

The list in (37) includes prosodic, suprasegmental and segmental alternations, all of which occur only when two specific morphemes are present in the same domain.

This mini typology shows that a number of predictions of CBP are borne out. First, non-adjacent elements can co-trigger a phenomenon, as long as they are introduced in the same phase (Amuzgo, Donno So, Guébie).Footnote 12 Second, a phase boundary intervening between triggers will prevent an otherwise doubly conditioned process from occurring (Amuzgo). Third, doubly triggered processes can span multiple words, if the phase domain contains multiple words (Donno So). Fourth, it is possible for more than two morpheme-specific reweightings to interact within a phase (Ende).

Among the case studies discussed here, we have seen that morphologically conditioned phonology with two triggers can affect an entire phase domain (Guébie), the edge or prominent position of a phase domain (Sacapultec, Amahuaca) or a prosodic domain that is smaller than a phase (Donno So). All of these effects are predicted by evaluating morpheme-specific reweightings in the phonological domain at phase boundaries, assuming that the phonological component can reference prosodic domains and edges. Some of the cases discussed here could be described as showing alternation of a root or specific target item within the phase (Amuzgo, Ende, Siouan). In a phonological account of doubly conditioned alternations, we predict alternations affecting elements that the phonological component can pick out, rather than specific morphosyntactic elements such as roots. More structural information is needed on cases where a root or target item seems to be affected without the whole word or phrase being affected. It may turn out that some of these are best described as purely phonological directional effects (e.g. a high vowel triggering regressive ablaut in Siouan), or as targeting a particular prosodic domain or boundary (e.g. the tone of a minimal prosodic word in Amuzgo). More data is needed in order to fully understand the locality of the phonological effect in these cases. Not predicted by a CBP account would be a particular morphosyntactic category – such as a root or a noun – being affected by morpheme-specific phonology, to the exclusion of the phonological or prosodic constituent containing it.

CBP makes specific predictions about doubly morphologically conditioned alternations that we do not expect to see in languages. Specifically, the Phase Containment Principle (Sande & Jenks Reference Sande and Jenks2018, Sande et al. Reference Sande, Jenks and Inkelas2020) in (38) specifies that morpheme-specific requirements will only affect the phonological form of morphemes introduced in the same spell-out domain, not in higher domains. Content introduced in higher phase domains will never be affected by morpheme-specific constraint-weight adjustments in lower phases.

-

(38)

As far as I know, morpheme-specific processes that affect hierarchically higher material across a phase boundary have not been described. For example, we do not find the realisation of a causative marker or other Voice head being determined by the lexical class of the object noun introduced in a lower DP phase.

4 Alternative analyses

In §2.1.2 and §2.2.3, Cophonologies by Phase was shown to straightforwardly account for phonological alternations that are sensitive to the presence of multiple simultaneous morphological triggers. This section considers whether alternative models of the morphology–phonology interface are also capable of modelling morphologically conditioned phonology with two triggers.

4.1 Distributed Morphology (without CBP)

Within traditional Distributed Morphology, there are two different ways of accounting for different phonological surface forms of a single morpheme: (i) suppletive allomorphy, and (ii) readjustment rules. A suppletive allomorphy account of doubly morphologically conditioned morphology is ruled out in §4.5 below, with reference to the Guébie facts. A suppletive approach may be an appropriate way to account for what have been called ‘lexical splits’, where a lexical item surfaces with two non-phonologically related forms in different contexts (Corbett Reference Corbett2015). However, it is not an appropriate model of phonological alternations that are subject to regular phonological constraints but only apply in the presence of specific morphemes or lexical items.

The second option relies on readjustment rules, or phonological rules sensitive to the morphemes present (Embick & Halle Reference Embick, Halle, Geerts, van Ginneken and Jacobs2005). There are a number of reasons to believe that a constraint-based phonology, such as the one adopted in CBP, makes better predictions than a rule-based one (Prince & Smolensky Reference Prince and Smolensky1993, Adler & Zymet Reference Adler and Zymet2020). Additionally, there is no theory of what readjustment rules can look like, thus there is no limitation to what a readjustment rule can do (see Siddiqi Reference Siddiqi2009). In a constraint-based phonology such as CBP, constraints are motivated by phonological markedness and faithfulness to inputs. Thus the only expected phonological alternations are those that optimise phonological outputs in some way. With constraint-based phonology plus morpheme-specific reweightings, as in CBP, we do not need the separate set of morpheme-specific phonological evaluation tools contributed by readjustment rules. I follow a line of recent literature that pairs Distributed Morphology with a constraint-based phonology, rather than adopting readjustment rules (Jenks & Rose Reference Jenks and Rose2015, Sande Reference Sande2017, Rolle Reference Rolle2018, Kastner Reference Kastner2019, among others).

4.2 Stratal OT

In Stratal OT (Bermúdez-Otero Reference Bermúdez-Otero1999, Reference Bermúdez-Otero and Trommer2012, Kiparsky Reference Kiparsky2000, Reference Kiparsky, Vaux and Nevins2008), words are built up from the root, and constraint-based phonological evaluation applies multiple times to the stem, word and phrase. The stem is a sub-word constituent where only a subset of affixes has attached, and the output of the stem-level phonology is the input to the word-level phonology. Constraints may be reranked at the stem and word levels, so that different phonological processes apply at the two levels. At the phrase level, multiple words, i.e. the outputs of the word level of evaluation, are evaluated together to determine the optimal output of an utterance. The phrase-level phonology applies across the board to all words, so no matter the morphological make-up of words in a given phrase, the phrase-level phonological grammar must be fully general, and cannot motivate morpheme-specific or exceptional alternations. Constraints can be ranked (or weighted) differently at the phrase level than at the stem or word level. The general structure of the theory is given in Table V.

Table V Structure of Stratal OT.

While Stratal OT allows for multiple phonological grammars in a single language, it does so in a way that is too restricted to account for doubly morphologically conditioned phonological alternations like those in Sacapultec and Guébie. In Sacapultec, the final vowel in a noun surfaces as long only when a possessive prefix is present, and only for a subset of lexical items. In Stratal OT, we could say that the possessive prefixes are stem-level affixes, while affixes that do not trigger lengthening, such as the stative prefix, are word-level affixes. Only at the stem level would constraints be ranked so as to derive final lengthening (FinalLength ⪢ Dep), while we would we get the opposite ranking at the word level, where other affixes are attached. While this model can differentiate between affixes that are triggers for final lengthening and those that are not, it predicts that we should see final lengthening at every stem-level evaluation. This does not mirror the facts, though. For some roots, this model would derive the correct output: /w-ak’/ → [waːk’]. However, for non-alternating roots, it incorrectly predicts lengthening where we do not find it: /w-am/ → [wam], *[waːm].

We could imagine a work-around where possessive prefixes are stem-level when alternating roots are present, but word-level with non-alternating roots. This modification would require sensitivity to particular morphemes, since whether the possessive prefix attaches at stem level or word level would depend on the particular root present. It would also loosen the distinction between stem- and word-level affixes, since a particular affix would need to be stem-level in some contexts but word-level in others. In fact, on this account, the distinction between stem and word grammars is no longer doing any work; instead, the reference to particular morphemes determines which grammar applies. This approach unnecessarily refers to the abstract notion of phonological stems and words, while also requiring reference to particular morphemes in order to derive final lengthening in the correct environment. In Cophonologies by Phase, on the other hand, individual morphemes need to be able to trigger constraint-weight adjustments, but we do not need to refer to the difference between stems and words. Instead, the boundaries for distinct phonological grammars are the same as those that limit syntactic operations: phase boundaries.

One benefit of Stratal OT is that it builds cyclicity into the grammar. Phonological evaluation applies multiple times to the same root, once at the stem level, once at the word level and once at the phrase level. With a cyclic derivation of this sort, we can derive phenomena like opacity, which are difficult to account for in a global evaluation model. In Cophonologies by Phase, cyclicity is also present, but rather than being specific to arbitrary stem vs. word boundaries, cycles are predicted to occur at independently necessary syntactic phase boundaries.

4.3 Cophonology Theory

In Cophonology Theory (Orgun Reference Orgun1996, Inkelas et al. Reference Inkelas, Orhan Orgun, Zoll and Roca1997, Anttila Reference Anttila2002, Inkelas & Zoll Reference Inkelas and Zoll2005, Reference Inkelas and Zoll2007), a master constraint ranking determines the overarching phonological grammar of the language. Individual morphemes can be associated with different cophonologies, or different rerankings of constraints that affect the master grammar. As words are built up one morpheme at a time, from the bottom up, phonology applies with the addition of each affix, and morpheme-specific information is no longer available after the first cycle of phonology applies to that morpheme, as in (39), from Inkelas & Zoll (Reference Inkelas and Zoll2007: 145).

-

(39)

In (39), the root first combines with suffix1. The cophonology associated with stem1 applies, and the morphosyntactic information about the identity of the root and suffix1 is no longer available for later stages in the derivation. The stem2 cophonology applies upon the addition of suffix2. Bracket erasure applies, such that stem2 only has access to the morphosyntactic information of stem1 and suffix2. The word only has access to stem2 and suffix3. This framework thus makes clear predictions about whether phonological alternations can be sensitive to more than one morpheme: only the root and the first suffix attached should be able to have a cumulative effect.

In Guébie, valency-changing morphemes on verbs can intervene between an alternating root and a harmony-triggering affix, as shown in (20). In (20b) we saw the verb undergoing harmony, despite the intervening affix. At the point in the derivation where harmony applies, the phonology has access to both the identity of the root and to the object enclitic, which are not linearly or hierarchically adjacent, as shown in (40).Footnote 13

-

(40)

At the stem level of evaluation, the phonological grammar has access to the morphosyntactic features of the root and the applicative. The applicative does not trigger harmony, so the phonological output of the stem level in Cophonology Theory would show faithfulness to input vowels. When the object enclitic is introduced, the word-level phonological grammar has access to the morphosyntactic features of that enclitic only; it can no longer access the identity of the root to determine whether harmony should apply. I conclude that the bracket-erasure predictions of Cophonology Theory are too limited to derive all cases of double morphologically conditioned phonology. The phase-based evaluation of CBP, on the other hand, allows for cumulative effects of multiple morphemes, even when there is an intervening affix, as long as the triggering morphemes are introduced within the same phase domain.

4.4 Indexed Constraint Theory

Cumulative or doubly conditioned effects pose a challenge for single-grammar theories such as Indexed Constraint Theory (Itô & Mester Reference Itô, Mester and Goldsmith1995, Fukazawa Reference Fukazawa1998, Pater Reference Pater, Bateman, O'Keefe, Reilly and Werle2007, Reference Pater and Parker2009). In Indexed Constraint Theory, there is a single, global constraint ranking, which applies across an entire language. One could index a harmony constraint to a particular set of grammatical morphemes (in this case 3rd person object markers), or to a particular lexical class (in this case an arbitrary set of roots), as in (41).

-

(41)

In Indexed Constraint Theory, both constraints in (41) would be present in the global phonological grammar, and in order to have any effect must both be ranked higher than general faithfulness constraints. If either of the morphological triggers, an object marker or a root of the appropriate lexical class, is present, harmony should apply. However, this prediction does not match what we see in the Guébie data; harmony only applies if both triggers are present in the spell-out domain.

Using weighted constraints in Indexed Constraint Theory, we could imagine a set of weights for the above constraints that results in a ganging effect. That is, the effect of the single constraint VHarmonyOM would not on its own be enough to trigger harmony, but the constraint could gang up with VHarmonyCl2 to result in harmony only when both constraints would otherwise be violated. This type of ganging effect could give us a surface form with global harmony when both the lexical and morphological trigger are present, but not otherwise. However, recall that full harmony in Guébie is not global. It only applies to elements introduced within the phase containing the trigger, or in earlier phases. Elements introduced in later syntactic phases, such as nominalisers on verbs, are unaffected by full harmony.

Pater (Reference Pater, Bateman, O'Keefe, Reilly and Werle2007) introduces locality specifications for indexed constraints, in order to limit the domain of the phonological effects associated with particular morphemes in Indexed Constraint Theory. Specifically, indexed constraints ‘apply if and only if the locus of violation includes a phonological exponent of the indexed morpheme’. This type of locality restriction does not differentiate between a vowel that immediately precedes the object marker (the root vowel) and one that immediately follows it (the nominaliser vowel), and so does not account for the word-internal locality restrictions of harmony in Guébie. Additionally, in cases such as Sacapultec possessives and Donno So definites, the exceptional indexed morpheme itself is not affected by the phonological alternation. Pater gives as an example of the type of phenomenon we would not expect to find under his locality restrictions a prefix triggering root-final consonant deletion in satisfaction of a NoCoda constraint. This unpredicted pattern is exactly the kind of alternation we see in Sacapultec, where a possessive prefix triggers a root-final alternation (in this case lengthening), and in Donno So, where a final definite marker triggers a tone melody on the initial prosodic domain within a noun phrase, but is not itself affected. Thus the locality predictions of Indexed Constraint Theory do not account for the locus of doubly morphologically conditioned phonological alternations.

The challenges for Indexed Constraint Theory in accounting for doubly conditioned phenomena are twofold: (i) how to prevent one of the constraints, VHarmonyOM or VHarmonyCl2, from having an effect when the other relevant trigger is not present, and (ii) how to account for the locality of application of the relevant phonological process. While ganging or local constraint conjunction could serve to address the first of these challenges, the second remains.

4.5 Emergent Morphology and Phonology

In Emergent Morphology and Phonology (Archangeli & Pulleyblank Reference Archangeli, Pulleyblank, Lee, Kang, Kim, Kim, Kim, Rhee, Kim, Kim, Lee, Kang and Ahn2012, Reference Archangeli, Pulleyblank, Hsiao and Wee2015, Reference Archangeli, Pulleyblank, Siddiqi and Harley2016, McPherson Reference McPherson2019), all surface allomorphs are listed in the lexicon, and constraints on allomorph selection determine which allomorphs surface in which contexts. In addition to listing all surface allomorphs in the lexicon, each allomorph can be associated with selection requirements, which limit the possible phonological forms they can surface next to. For example, Archangeli & Pulleyblank (Reference Archangeli, Pulleyblank, Hsiao and Wee2015) argue that there are two listed allomorphs of the 3rd person singular object prefix in Kinande (Bantu), /mʊ̀/ and /mʊ́H__/, where the latter, the H-toned allomorph, selects for a H-toned element immediately to its right. In this framework, the bulk of the work of deriving surface forms happens in the lexicon: all allomorphs are listed, and some have phonological selection requirements.

In Guébie, vowels in an alternating root surface with the features of an object enclitic vowel, when present (§2.2.2). For a root like /bala3.3/, then, we would need to list at least the allomorphs in (42). The underlined form is the default allomorph.

-

(42)

An examination of these allomorphs suggests that whenever there is a following [ɔ], the [bɔl3] allomorph is chosen. However, this is not always the case in Guébie. Recall that both the 3rd person singular object enclitic and the passive suffix on verbs have the form /ɔ2/. We only see /bala3.3/ surfacing with [ɔ] when the following [ɔ2] comes from an object enclitic. There is no vowel alternation in passive contexts. So we would need to complicate the selection requirements of each allomorph as in (43).

-

(43)

The selection requirements of allomorphs in (43) are quite similar to vocabulary-insertion rules in Distributed Morphology (Halle & Marantz Reference Halle, Marantz, Hale and Keyser1993, Embick & Noyer Reference Embick, Noyer, Ramchand and Reiss2007). Whether we are considering listed allomorphs in Distributed Morphology, or listed allomorphs in Emergent Morphology and Phonology, all alternating verbs would need to have at least five lexically listed allomorphs, as in (43). In every case, alternating verbs would have a form with [ɔ], another with [a], another with [ɛ] and another with [ɪ]. It just so happens that each of these forms appears only before a 3rd person singular object marker that begins with the same vowel, [ɔ a ɛ ɪ] respectively.

With lexically listed allomorphs like those in (43), the lexicon is drastically larger than in a CBP account. And in Emergent Morphology and Phonology, the generalisation that verbs surface with the same vowel quality as the enclitic is lost, as all allomorphs are simply listed together with their insertion contexts. In CBP, on the other hand, a single phonological grammar, in which a constraint motivating vowel harmony is weighted more strongly than a faithfulness constraint, is responsible for accounting for harmony in all alternating contexts. In CBP we need only list one allomorph of each verb, noun and affix; the phonological component determines the appropriate output form.

4.6 Item-based approaches

A possible autosegmental item-based approach would take the form of a trigger morpheme containing a floating feature, mora or segment, while a target morpheme or segment is defective or underspecified, subject to alternation in a way that other fully specified morphemes and segments are not (cf. Lieber Reference Lieber1987). Only when both the defective target morpheme and the trigger morpheme with extra floating material are present would an unfaithful surface form appear. This type of analysis has been proposed for Hungarian length alternations in certain stems, which is triggered only by certain affixes (Stiebels & Wunderlich Reference Stiebels and Wunderlich1999), Dakota ablaut (Kim Reference Kim2002), Estonian vowel alternations on certain nouns in certain morphosyntactic contexts (Spahr Reference Spahr2012), German umlaut (Trommer Reference Trommer2016) and Diegueño lengthening of some nouns in plural contexts (Zimmermann Reference Zimmermann2017).Footnote 14 What is lacking in these accounts is an examination of case studies where the phonological alternation applies between non-adjacent morphemes, or with intervening phase boundaries.

The crucial challenge for a purely item-based approach is how to account for the locality domains of the cross-linguistic patterns discussed in §3, specifically (i) why should intervening phase boundaries block double conditioning?, and (ii) how should we account for long-distance double conditioning across multiple words and morphemes? I illustrate this challenge with data from Amuzgo, Donno So and Guébie.

Recall that in Amuzgo, the lexical class of a verb and the person features of a subject co-determine the surface tone on a verb. However, when a causative phase head intervenes, this process no longer applies. Whether or not a causative morpheme is present, the subject and verb are neither hierarchically nor (necessarily) linearly adjacent; for example, the potential and incompletive prefixes intervene between subject and verb, but the verb still shows tonal alternations with person, as in (44) (Kim Reference Kim, Panacar and Léonard2016: 203).

-

(44)

In an autosegmental account, we would have to assume that the subject, which precedes verbal prefixes, has a floating tone that gets associated with the verb root while not interacting with the intervening prefix. This would involve crossing association lines in autosegmental phonology, a structure that is typically not assumed to be possible. This principle carries much of the predictive weight of the autosegmental framework (Goldsmith Reference Goldsmith1976). Even if we allow for crossing association lines, it is not clear, under a purely item-based approach, how we can ensure that causative prefixes block association of the floating subject tone to the verb, while other prefixes do not.

There is a further problem for an item-based analysis of Amuzgo, which is that subject persons do not always assign the same tone to verb melodies; between five and eight tone melodies are assigned by each person feature, depending on the lexical class of the verb. Kim (Reference Kim, Panacar and Léonard2016) shows that there is no combination of underlying tones of subjects and verbs that can account for the surface tone patterns in Amuzgo. In other words, there is no set of floating subject tones that can combine with underlying verbs tones to derive the surface patterns. This lack of concatenative behaviour leads Kim to analyse the Amuzgo doubly conditioned tone patterns as due to a cophonology, rather than as item-based.

Recall that in Donno So, too, the triggering morphemes of the doubly conditioned process are not always linearly adjacent, and trigger a tonal overlay on multiple words: [N Adj Num]LH Def, where the underlined morphemes are triggers for the tonal melody that affects the domain in brackets. Additionally, for many Guébie speakers, doubly conditioned vowel harmony can apply in non-local contexts, when affixes intervene, affecting multiple morphemes, as in (20). It is not clear why, in an autosegmental or other item-based approach (e.g. Gradient Symbolic Representations; Rosen Reference Rosen2016, Smolensky & Goldrick Reference Smolensky and Goldrick2016), intervening affixes should alternate when an alternating root and object marker are present, but not when a non-alternating root and object marker are present. If the object marker is associated with floating features that trigger harmony on underspecified vowels, we should expect vowels to always or never alternate in the presence of an object marker. Whether an affix vowel alternates should not be sensitive to the quality of the root vowel or identity of the root. In a CBP account, though, when two triggers (an object marker and alternating root) are present in the same domain, and the alternation applies to the entire spell-out domain, intervening affixes are predicted to alternate.

The locality effects of morphologically conditioned phonology with two triggers applying across intervening morphemes and words and blocking by intervening phase boundaries pose a challenge for an item-based account. While some phenomena might best be modelled as item-based, key assumptions of autosegmental phonology would need to be sacrificed to account for the doubly conditioned phonology facts.

5 Conclusion

A diverse array of languages show phonological alternations or requirements that only hold in the presence of two simultaneous morphological triggers. While this phenomenon presents a challenge for many extant frameworks of the morphology–phonology interface, as discussed in §4, Cophonologies by Phase can straightforwardly account for the attested patterns, using the same tools that are needed to account for other morphologically conditioned phonological alterations. By associating reweighting of phonological constraints with particular vocabulary items and allowing those cophonologies to have scope over syntactic phases, CBP easily accounts for, and in fact predicts, phonological alternations that only appear in the presence of multiple morphological triggers.

While morphologically and lexically conditioned phonology have often been called exceptional (e.g. the ‘exception features’ of Chomsky & Halle Reference Chomsky and Halle1968 and Lightner Reference Lightner and Worth1972, or the ‘patterned exceptions’ of Zuraw Reference Zuraw2000, Reference Zuraw2010), they are widespread, and likely found in every human language. Rather than ignoring them or modelling them in an exceptional way, Cophonologies by Phase builds morpheme-specific phonological requirements into the grammar as part of the vocabulary entry.

Previous work has argued that CBP outperforms other models of the morphology–phonology interface because it can account for morpheme-specific phonological effects that cross word boundaries, but are restricted by syntactic phase boundaries (Sande & Jenks Reference Sande and Jenks2018, Sande et al. Reference Sande, Jenks and Inkelas2020). This paper adds to the arguments in favour of CBP by showing that it can account for another phenomenon – morphologically conditioned phonology with two triggers – which is challenging to account for in alternative frameworks.