1 Background

Blust (Reference Blust2017) argues that, contrary to common belief, a surprising number of sound changes are conditioned in ways that appear to be unrelated to the phonetic environment. In other words, the relationship between the type of change taking place and the environment in which it occurs appears to have no linguistic significance in these cases, an observation that holds true even where the form of the change shows that speakers are aware of natural classes. For example, in the Papuan language Orokolo, intervocalic *t has become /k/ between vowels of the same or ascending height, but has become /l/ or /r/ between vowels of descending height, a change that has no clear phonetic motivation, but which presupposes that speakers are aware of the categorial membership of vowels as defined by height.

An unusual set of sound changes in Miri, a moribund Austronesian language spoken in northern Sarawak, Malaysian Borneo, initially appears to fit this perplexing pattern. However, further study shows that this change is in fact phonetically motivated in ways that involve the complex operation of the aerodynamic voicing constraint (Ohala Reference Ohala and MacNeilage1983, Reference Ohala1997, Reference Ohala, Lee and Zee2011). Despite this explanatory success, the proposal advanced here does not quite succeed in eliminating all odd conditions, as several details of these changes in Miri (and other related languages) continue to elude any straightforward phonetic explanation.

2 The problem

Voiced obstruents have long been known to embody an inherent articulatory contradiction: airflow is needed to produce voice, and suppression of airflow is needed to produce an obstruent. Although many languages are able to live with this contradiction, many others have found ways to avoid it. The most common of these avoidance strategies undoubtedly is final devoicing, found in many of the world's languages (Blevins Reference Blevins2006, Iverson & Salmons Reference Iverson, Salmons, van Oostendorp, Ewen, Hume and Rice2011). Other, more exotic, strategies employed to cope with the same phonetic dynamics are the development of typologically rare voiced aspirates from earlier geminates in the Dayic languages of northern Sarawak (Blust Reference Blust2006, Reference Blust2016), and the nasalisation of final voiced stops as an alternative to final devoicing in a number of the languages of insular Southeast Asia (Blust Reference Blust2018).

Quite apart from how the contradictory specifications for voiced obstruents affects these consonants themselves, the articulation of voiced obstruents also affects the perception of following vowel height as a result of physical constraints on the production of voice. Voice requires air to pass through the larynx, but with a stop there is no outlet, increasing the supraglottal pressure, and forcing the larynx to lower, which momentarily lengthens the pharyngeal cavity, an effect that continues briefly after the occlusion is released. When this happens, it alters the acoustic properties of the resonating chamber, thus lowering the frequency of the first formant, an effect that correlates perceptually (or in articulatory terms) with greater vowel height (Hudgins & Stetson Reference Hudgins and Stetson1935).Footnote 1

This tendency is well established for the Mon-Khmer languages of mainland Southeast Asia (Henderson Reference Henderson1965), and Thurgood (Reference Thurgood1999: 205–209) documents it as well for the Chamic (Austronesian) languages that underwent areal adaptations to their Mon-Khmer neighbours. In these languages, which are subject to registrogenesis, voiced obstruents have two prominent effects on following vowels: they trigger breathy voice, which spreads through sonorants and possibly *s and *h, and raise the height of following vowels unless this effect is blocked (in most languages) by a medial voiceless stop.

The problem addressed here is superficially different, in that breathy voice is absent, low vowels appear to front rather than raise following a voiced obstruent earlier in the word, and high vowels are lowered in some contexts, but diphthongise in others unless a voiced obstruent occurs earlier in the word, in which case they do not change. At least initially, then, voiced obstruents appear to condition two fundamentally distinct phonological processes in the same language, one fronting low vowels and the other suppressing either the breaking or lowering of high vowels. The challenge is to show why this type of conditioning should exist.

3 The language

Miri is an Austronesian language apparently still spoken by a few people near the coastal city of the same name just south of the mouth of the Baram river in northern Sarawak, Malaysian Borneo (Abdul Ghani & Ridzuan Reference Ghani, Aminah, Ridzuan and Martin1992: 133–134). The data in this paper were recorded from April to June 1971, at which time the language was already being abandoned by many community members who preferred to be considered ‘Malays’ (for a perspective on language shift from Miri to Malay from a slightly later time period see Abdul Ghani & Ridzuan Reference Ghani, Aminah, Ridzuan and Martin1992).Footnote 2

As argued in Blust (Reference Blust1974), and repeated in several later publications, Miri belongs to the Berawan-Lower Baram division of North Sarawak, a collection of some 30–35 languages and dialects. Among the extant members of this group, it is most closely related to Narum, which is spoken near the market town of Marudi, about 35 miles inland as the crow flies, but closer to 57 miles as the river winds. It is more distantly related to Kiput, Belait and the Berawan languages within the Berawan-Lower Baram group, and to Bintulu, the Kenyah languages and Dayic (Kelabit-Lun Dayeh) in other primary branches of North Sarawak.

The Miri phoneme inventory is shown in (1).

(1)

The voiceless stops of Miri are unaspirated, some /m/ and /n/ may be postploded medial nasals [mᵇ] and [nᵈ] (nasals followed by an extra-short voiced stop), and /r/ is an alveolar tap or trill. The vowels have their canonical values, except that /e o/ are usually laxed when not preceding another vowel, and are long in the final syllable, which carries primary stress (hence /ages/ → [aˈgɛːs] ‘sandfly’). Distributionally, /ə/ and /a/ contrast in the penult, but have merged as the low vowel in the ultima, and are in free variation in the antepenult, with a preference for /a/.

Like almost all coastal languages of Sarawak, Miri has been heavily exposed to Malay since the establishment of the politically and culturally dominant Sultanate of Brunei in 1368. In more recent years, it has also been exposed to the national language, Bahasa Malaysia, which derives from a southern peninsular form of Malay. Because Malay loanwords may have been introduced at different time periods and from different dialects, they will be treated with caution in this paper: many reflect the same patterns of change found in the native vocabulary, but where there are exceptions these may be explainable by the chronology or source of borrowing.

4 The data

The data relevant to conditioning of vowel qualities by a preceding voiced obstruent will be presented in two parts, beginning with the effects on low vowels.

4.1 Low vowel fronting

Low vowel fronting is found in a number of the languages of northern Sarawak (Blust Reference Blust2000). In most of these languages a low vowel fronts immediately after a voiced obstruent. For the North Sarawak languages this means any of eight inherited consonants, a series of plain voiced obstruents at labial, alveolar, palatal and velar places (Proto-North Sarawak (PNS) *b, *d, *ʤ, *g), and a parallel series of typologically rare voiced aspirates (PNS *bʰ, *dʰ, *ʤʰ, *gʰ).Footnote 3 In addition, some languages, such as Miri, have developed historically secondary /b/ and /ʤ/ through glide fortition, including the automatic glides between *i or *u and a following unlike vowel, and these also trigger low vowel fronting (LVF), as in *lia ([lija]) > ləʤeh ‘ginger’ or *dua ([duwa]) > dəbeh ‘two’. The most common form of LVF is seen in the Long Terawan dialect of Berawan (LTB), where *a is fronted immediately after a voiced obstruent regardless of its position in the word, as in PNS *adaɁ > LTB adi ‘shadow’, *batu > bittoh ‘stone’, *Ratas (> *gatas) > gita ‘milk’, but not after other consonants, as with *mata > mattəh ‘eye’, *paɁa > paɁəh ‘thigh’, *kami > kammeh ‘1pl excl’, *laki > lakkeh ‘male’, etc.

Miri differs from this pattern in targeting low vowels only in the last syllable, regardless of the distance to the trigger. In *adan > aden ‘name’, *tugal > tugel ‘dibble stick’ and *uban > uben ‘grey hair’, where the trigger is the onset of the final syllable, LVF appears to follow the same pattern as in LTB. However, in reflexes of words with an initial voiced obstruent and two low vowels, like *daɁan > daɁen ‘branch’ and *ʤalan > ʤalen ‘path, road’, the trigger targets a low vowel in the final syllable even though it immediately precedes a low vowel that is unaffected (cf. PNS *daɁan > LTB diɁən ‘branch’, *ʤalan > ilan ‘path, road’). It has been suggested that this pattern might be dissimilatory, but in *baRu > baruh ‘new’, *daɁi > daɁih ‘forehead’ and a number of other examples, dissimilation is not an option.

Like some other languages, Miri reflects the PNS voiced aspirates as voiceless fricatives or stops, but fronts a following low vowel, which shows that these consonants were still voiced obstruents at the time of LVF: *əbʰaɁ > feɁ ‘fresh water, river’, *mədʰan > masen ‘to faint, pass out’, *əʤʰa > seh ‘one’, *pəgʰəl > məkel ‘to sleep’. Finally, some words, such as məkel, were recorded only in their active verb forms with homorganic nasal substitution, rather than in their unaffixed nominal base form.

Two interrelated features of LVF in Miri distinguish it from this phenomenon in most other languages. The first, which has been mentioned already, is that a low vowel is fronted only in the last syllable (I recorded no suffixes, and hence no synchronic alternations between /a/ and /e/). As a result, trigger and target are often separated by a VC sequence. Where the consonant of such a sequence is a supraglottal voiceless stop or a nasal, it neutralises the effect of the preceding voiced obstruent. Thus, LVF is seen in PNS *baRa > bare ‘ember’, *busak > buek ‘flower’, *ʤəlaɁ > ʤəleɁ ‘tongue’, but not in *bituka > batukah ‘intestines’, *dəpa > dəpah ‘fathom’, *gatəl > gatal ‘itchy’, *bana > banah ‘husband’, *danaw ‘lake’ > danaw ‘pond’, *ʤaməɁ > ʤamaɁ ‘dirty’. This second feature of LVF in Miri is particularly puzzling, since in Narum, its closest living relative, the fronting of last-syllable vowels may also be triggered at a distance, but there are no blocking consonants (thus *dəpa > dəpeəh ‘fathom’, *gatəl > gatel ‘to itch, itchy’, *danaw > daniəw ‘lake’, *ʤaməɁ > ʤameɁ ‘dirty’). As a result, LVF in bases with a trigger + blocking consonant patterns like bases without a trigger in Miri, but like bases with a trigger in Narum, as will be shown below.

4.2 Vowel breaking: the major pattern

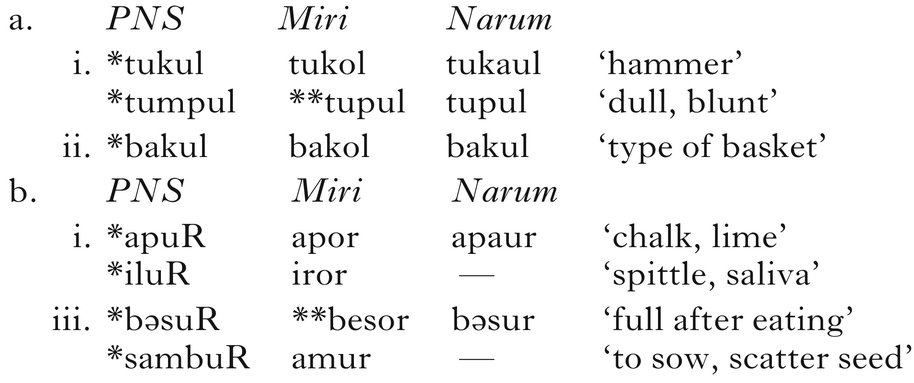

Many languages in Sarawak, particularly those on or near the coast, show a pattern of vowel breaking or diphthongisation in which *i, *u and occasionally *a (which was raised to /e/) developed a mid-central offglide before -k and -ŋ, but not -g (hence -iək, -iəŋ, -ig) and a mid-central onglide word-finally. Table I summarises variations in this pattern across ten language communities.

Table I Patterns of vowel breaking in languages of Sarawak (predictable glides are omitted). KT (Kampung Teh) and KK (Kampung Kekan) are two subdialects of Dalat Melanau. Adapted from Blust (2013: 655).

4.3 Vowel breaking in Miri

Miri differs from most of these languages in both positive and negative respects. Specifically, vowel breaking occurs before some final consonants other than velars, and is suspended in some cases where it would be expected. Like most North Sarawak languages, Miri offers many challenges in its historical phonology, and perhaps the most puzzling of these is a large set of examples in which high vowels in the final syllable show no change of shape, neither breaking nor lowering.

The full range of reflexes is given in Table II. The diphthongs -aj/-aw are written -ai/-au before a consonant, including the historically secondary -h. Numbers represent instances of each type of change attested in the data cited below: 0 = either no examples of this sequence were available in reconstructed forms, or examples were available, but none showed this change; postvocalic vowels and glides were not counted; palatals and /f/ do not occur as codas, and -p and -m are rare (the sole example of *-um in my data is found in məɲum ‘to drink’).

Table II All reflexes of last-syllable high vowels in Miri, by frequency.

To summarise, lowering of high vowels in the last syllable occurs in 22 cases and breaking in 43, and there is no change in 45. Since ‘no change’ means neither breaking nor lowering, there are 65 cases in which a last-syllable high vowel either diphthongises or lowers, and 45 in which no change occurs. The puzzle to be solved, then, is why there is no change in 45 of 110 etymologies, while either vowel breaking or lowering occurs in 65 others, often in what appears to be the same environment. In short, at first glance it appears to be impossible to predict when a high vowel undergoes a change (breaking or lowering) or remains unchanged.

At face value, Table II shows a 65–45 split between high vowels in the final syllable that underwent either breaking or lowering and those that remained intact. However, when the voicing of preceding obstruents is taken into account, nearly every example falls into place. This is particularly surprising, since the trigger in LVF is a preceding voiced obstruent. With final-syllable high vowels rather than low vowels, on the other hand, a preceding voiced obstruent appears to act as a suppressor, preventing a process that would otherwise be much more general. In other words, last-syllable vowels are affected by an unobstructed preceding voiced stop in one of two ways: (i) *a > e (rarely i); (ii) *i/u fail to become -aj/-aw or -e/-o. What feature these two functions share is at first sight a mystery.

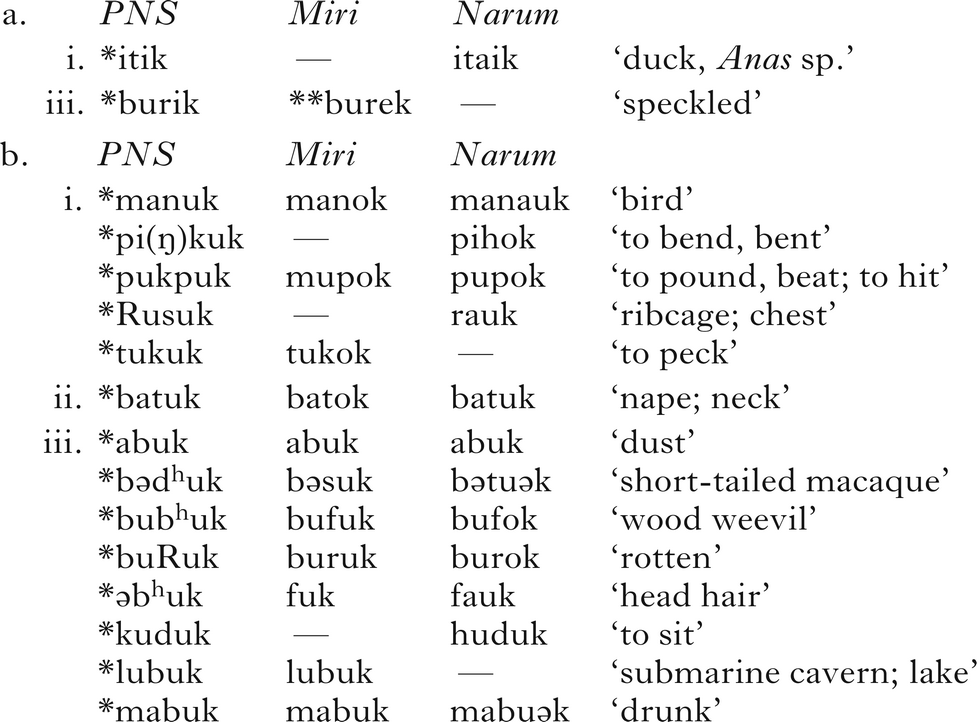

The most systematic way to present the relevant data is probably by citing developments in one environment at a time (reconstructions with a high vowel preceding a final labial or /g/ are rare, and are omitted here). Note that where glosses of reconstructions and reflexes differ, the former appears before a semicolon and the latter after it. A double asterisk here and elsewhere marks a form as irregular. In all environments, the subtypes are (i) no preceding voiced obstruent, (ii) a preceding voiced obstruent with an intervening blocking consonant and (iii) a preceding voiced obstruent without an intervening blocking consonant.

Finally, Narum examples are included for ease of comparison, but will not be discussed further.

4.3.1 Word-final high vowels

(2)

The first difference to note between the languages in Table I and Miri is that vowel breaking in most languages of Sarawak changed *-i/u to -əj/ -əw, but in Miri these have become -ai/-au or -aj/-aw, with a low vowel diphthongal nucleus. However, Miri may have begun with *-i > -əj and *-u > -əw, since *a and *ə merged as /a/ in the final syllable: PNS *anak > anak ‘child’, *əpat > pat ‘four’, *nakan > nahan ‘small jackfruit sp.’, *ənəm > nam ‘six’, *gatəl > gatal ‘to itch’, *ʤəkət > ʤukat ‘to burn fields’.Footnote 8

The second difference to note is that, while Miri followed a common Sarawak pattern in adding -h after final vowels, it also added -h after both historically derived and inherited word-final diphthongs, as in the above examples and *anaj > anaih ‘termite’, *m-ataj > mataih ‘to die; dead’, *sapaw > apauh ‘roof’, *takaw > nakauh ‘to steal’ (next to *danaw ‘lake’ > danaw ‘pond’, *laŋaw > laŋaw ‘housefly’, *tapaj > tapaj ‘fermented rice’, etc., which are unchanged). Aspirate addition appears to have been regular after derived diphthongs from earlier word-final high vowels, but is sporadic after original final diphthongs. In words that ended in *-is or *-us (see (7) below) it appears that vowel breaking preceded loss of the final consonant, since otherwise these words would have ended in a vowel at the time of diphthongisation, and, as already noted, words that earlier ended in *-i/-u seem invariably to have resulted in -aih/-auh.Footnote 9

What is most noteworthy in these examples is the difference between the reflex of word-final high vowels in subtype (iii), where a preceding voiced obstruent occurs without an intervening blocking consonant (fəlih, daɁih, tadih, ubih, abuh, etc.), as against subtypes (i) (no preceding voiced obstruent) and (ii) (preceding voiced obstruent with blocking consonant). I will return to this point below.

4.3.2 Vowels preceding word-final *Ɂ

(3)

The pattern of breaking of high vowels before word-final glottal stop does not differ markedly from that of word-final high vowels. Although there are fewer examples, categories (i) and (ii) clearly pattern alike, showing the transformation of high vowels into diphthongs, while category (iii) preserves the high vowels intact.

4.3.3 Vowels preceding word-final *t

(4)

The pattern of breaking before word-final /t/ differs in an important particular from the preceding sets of examples, in that *i diphthongises, while *u lowers. Again, there are relatively few examples, although the pattern is consistent. No examples of *-it with a preceding voiced obstruent in the word were recorded, and (4b.ii) is irregular, since the medial voiceless stop should have blocked the suppression of lowering seen in (4b.iii).

4.3.4 Vowels preceding word-final *d

(5)

No examples of *-id or *-ud with a preceding voiced obstruent were recorded, but even given this limitation, a clearly divergent pattern is seen in the (i) set here, namely that high vowels are unchanged. Since there are five examples that conform to this pattern, and no exceptions, it seems reasonable to hypothesise that vowel breaking in Miri is suppressed not only when there is an unblocked voiced obstruent earlier in the word, but also when a final-syllable high vowel immediately precedes a stop that is, or was historically, voiced (Miri appears to be undergoing final devoicing, but the process was not yet complete at the time my data were recorded). Although this is not a condition for LVF, the available evidence leaves us at liberty to assume that voiced obstruents suppressed vowel breaking or lowering whether they preceded or followed a high vowel. If this condition is accepted as plausible, then these apparent exceptions can be seen as a subtype of the general principle that a preceding voiced obstruent suppresses vowel lowering.Footnote 12

4.3.5 Vowels preceding word-final *n

(6)

Examples of -in were recorded only for subtype (i), but even so it is clear that *i and *u in this set pattern as they do before word-final /t/, namely with breaking of *i and lowering of *u. Although the (ii) and (iii) sets for *-un contain only one example each, these are consistent with the wider pattern in which a high vowel remains intact in set (iii).

4.3.6 Vowels preceding word-final *s

(7)

Examples of *-is and *-us are limited, and in every case *s has disappeared. Since -h is not found after any diphthong that resulted from loss of *-s, it is tempting to see the order of changes as (i) vowel breaking, (ii) addition of -h, (iii) loss of *-s. However, Narum has also lost final *s, but without adding -h, and as already noted, inherited *-aj and *-aw sometimes added -h and sometimes did not, leaving the matter in limbo.

4.3.7 Vowels preceding word-final *l and *R

(8)

Neither of these sets offers a clear picture of how high vowels developed preceding final liquids, in part because of apparent irregularities and in part because no examples of *-il or *-iR were recorded. It is possible that the Miri reflex of *sambuR is /amᵇur/, with a postploded medial nasal, since these segments are well attested in Narum (Blust Reference Blust1997b).

4.3.8 Vowels preceding word-final *k

(9)

Type (9a) is poorly represented, but (9b) provides valuable information. Here, where most languages of Sarawak show vowel breaking with a mid-central offglide, Miri has vowel lowering (shared with Matu Melanau and Uma Juman Kayan). Most importantly, there is complete agreement in the four examples of sets (9b.i) and (9b.ii) in showing high vowel lowering, and the seven examples of set (9b.iii) in showing suppression of lowering.

4.3.9 Vowels preceding word-final *ŋ

(10)

Although there are fewer known cases of high vowels preceding a final velar nasal than preceding final *k, the pattern is reasonably clear, namely that high vowels lower in this environment unless preceded by an unblocked voiced obstruent. These patterns are summarised for ready reference in Table III, which is more fine-grained than Table II, in recognising subtypes (i)–(iii).

Table III Patterns of vowel breaking and suppression in Miri. The first number in parentheses is the number of supporting examples; the second the number of contrary examples.

With regard to the patterns in Table III, it is clear that subtype (i) is the most robustly attested, since it does not require a voiced obstruent earlier in the word, and so includes a wide range of other possibilities. Under this condition, 60 examples show either breaking or lowering of a last-syllable high vowel, and five do not. Subtype (iii) is the second most robustly attested pattern, with 33 supporting examples and two counterexamples, since here all that is required is a voiced obstruent earlier in the word, without an intervening blocking consonant. The rarest pattern is subtype (ii), which requires both a voiced obstruent earlier in the word and an intervening blocking consonant that neutralises its effect, thus making it like subtype (i); here we have eight supporting examples and two counterexamples, suggesting that breaking consonants function less consistently than voiced obstruents. In total, there are 101 supporting cases and nine contrary ones, for a predictability rating of nearly 92%. This shows that there is a rather consistent pattern in which an unblocked preceding voiced obstruent suppresses the breaking or lowering of last-syllable high vowels in Miri reflexes of Proto-North Sarawak.

The contrary cases fall into three categories: five under subtype (i), in which vowel breaking or lowering is expected, but does not occur (fəkuɁ, fuluɁ, amin, tupul, utuŋ), two under subtype (ii), in which a voiced obstruent is found earlier in the word, but its suppressive effect on vowel breaking or lowering should have been neutralised by a blocking consonant (*buɲi > muɲih, bukut), and two under subtype (iii), in which an unobstructed voiced obstruent is found earlier in the word, but vowel breaking or lowering still occurs (bəsor, burek). Two of these may be Malay loans (tupul, from Malay tumpul ‘dull, blunt’, and burek, from Malay burek ‘speckled’), and one may be an Iban loan (muɲih, possibly from Iban muɲi ‘make a sound’), but the others appear to be native, and their irregularity is unexplained. The only other qualification that might be made is that /s/, which is rare in medial position, may function as a blocking consonant in bəsor, like the voiceless stops.

The recognition that a general process of high vowel breaking or lowering is usually suppressed in Miri if an unblocked voiced obstruent is found earlier in the word is certainly significant in itself, but its significance is magnified enormously when it is recognised that low vowels in the final syllable are fronted under the same condition, since, at least initially, these phenomena appear unrelated. The two processes can be compared side-by-side, as in (11).

(11)

When first recognised, a correlation of this detail and robustness in the conditioning of what appear to be distinct phonological processes is startling. However, as will be seen below, much of what makes this correlation surprising is the way in which it has been conceptualised (or misconceptualised), due to statistical biases in the original data sample. Before examining a possible phonetic explanation for these facts in Miri it will repay our efforts to first briefly examine the behaviour of loanwords.

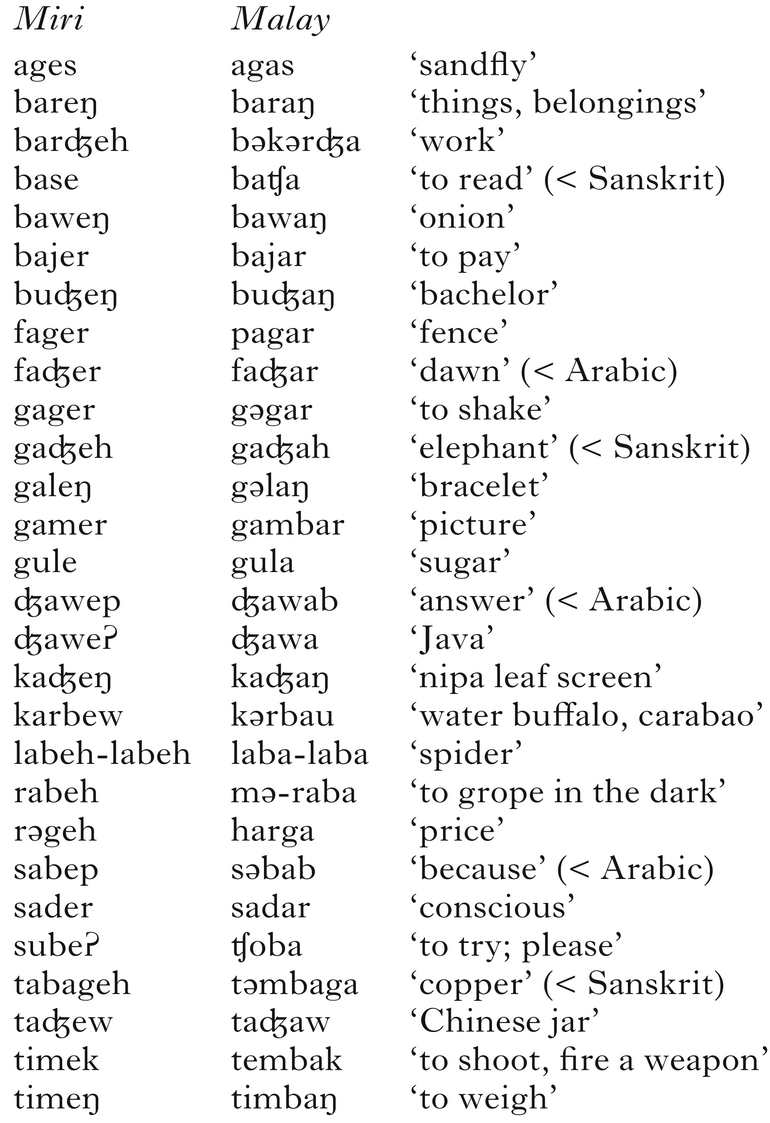

5 Loanwords

It was noted earlier that nearly all coastal languages of Sarawak have borrowed fairly heavily from Brunei Malay during the six and a half centuries since the establishment of the Brunei sultanate in 1368, and Miri is no exception. What emerges with some clarity from this data is that LVF occurs in many Malay loans, as seen in (12).

(12)

By contrast, high vowel breaking (HVB) is almost totally absent in known or likely Malay loanwords in Miri, as shown in (13). The expected forms are given in parentheses.

(13)

Because high vowels are commonly lowered before word-final velars in Standard Malay and various Malay dialects, the significance of Miri uneŋ, Malay kuniŋ ‘yellow’ or Miri useŋ, Malay kuʧiŋ ‘cat’ is difficult to assess. The only unambiguous example of HVB in a word that almost certainly is a Malay loan is Miri lakauɁ ‘profit in business’, Malay laku ‘having value, selling well’. The presence of a final glottal stop in both lakauɁ and pakuɁ points to Brunei Malay as the most likely source of these loans.

This rather striking difference in the application of LVF or HVB to known or likely loanwords suggests that HVB occurred before the beginning of large-scale borrowing from Malay, while LVF occurred after many Malay loans had entered the language, and were treated like part of the native vocabulary.

6 Distributional evidence for an implied phonetic motivation

There is no question that both LVF and HVB in Miri are conditioned in an unusual way, but the major challenge they present is how to explain why they are conditioned in the same way. At first there seems to be no connection between the fronting of low vowels and the breaking or lowering of high vowels. Add to this that both innovations can be conditioned at a distance, and share a set of blocking consonants that neutralise these phonological processes in seemingly opposite ways (blocking an active process with /a/, and blocking the suppression of an active process with /i u/), and the mystery deepens.

Faced with such data, it would be easy to conclude that there is no phonetic basis for either of these processes in Miri. However, the fact that LVF has a discontinuous distribution in northern Sarawak (Blust Reference Blust2000), and has also been reported over a largely continuous area in northeast Luzon (Reid Reference Reid and Harlow1991, Himes Reference Himes2002, Lobel Reference Lobel2010, Reference Lobel2013, Robinson & Lobel Reference Robinson and Lobel2013: 136–137), clearly implies that at least this change must be driven by some universal phonetic mechanism, and, given the similar patterning of high vowel breaking, we have little choice but to conclude that the two phonological processes must share a common phonetic cause. For most sound changes that are phonetically motivated, the mechanism that lies behind them is readily recognisable. What makes this problem difficult is that the phonetic mechanism that unites LVF and HVB as different expressions of a single targeted outcome is not immediately apparent.

7 Is low vowel fronting really fronting?

It now seems likely that the principal reason for this lack of phonetic transparency is that the problem has been framed in a way that obscures the relationship between its parts. After all, what connection can the fronting of low vowels and the breaking or lowering of high vowels possibly have?

The change of *a to /e/ or /i/ when a voiced obstruent is found earlier in the word was called ‘low vowel fronting’ in Blust (Reference Blust2000), since if this was a raising process there is no clear reason why *a did not sometimes raise to a back or central vowel, or why the schwa is never raised to a high central vowel, but this is unattested in any of the nine North Sarawak languages known to have undergone this change, as shown in (14).

(14)

In addition, Berawan was treated as one language, although there are dialect differences in how this innovation is realised. *a > i is found in Long Terawan Berawan, for which the best data is available, but *a > æ in the Long Jegan dialect suggests that the effect of a preceding voiced obstruent is to front a low vowel, with raising as an incidental by-product. However, it now appears that the essential feature of LVF is raising, and this recognition enables us to connect the otherwise mysterious identical conditioning of LVF and HVB in Miri in a phonetically plausible way.

To start with LVF, if we consider a wider set of languages with similar processes of change to low vowels following voiced obstruents, it becomes clear that the North Sarawak languages, for whatever reason, have not used the full range of potential options. A number of languages on the Pacific coast of Luzon and neighbouring inland areas, as well as several non-standard Malay dialects, also show changes to *a only after a voiced obstruent. Although this was noted in Blust (Reference Blust2000: 306ff), recourse to non-front options was not fully appreciated, and the number of such cases has continued to increase since 2000 as more data has become available. The full range of conditioned changes to *a following a voiced obstruent can now be stated as in (15).

(15)

Both Lobel (Reference Lobel2013) and Robinson & Lobel (Reference Robinson and Lobel2013: 138) follow Blust (Reference Blust2000) in using the term ‘low vowel fronting’ for innovations that affect *a only after a voiced obstruent, since these usually result in a front vowel outcome. However, as seen above, in both Northern Alta and Ilongot, two languages that are not closely related, the outcome is a high central vowel, and in Manide, which is not in proximity with or closely related to either of the foregoing languages, *a has become either e or u after voiced obstruents.

Blust (Reference Blust2000), after describing and attempting to explain the data in the North Sarawak languages, notes several of these Philippine cases, and in addition states that ‘Collins (Reference Collins and Collins1993, Reference Collins1998) and Jaludin (Reference Jaludin2000) have drawn attention to vocalic effects after voiced obstruents in several Malay dialects spoken on or near Borneo, where the process seems clearly to be one of raising rather than fronting’ (Reference Jaludin2000: 307). These cases are given in (16).

(16)

Although their discussion is very brief, Sneddon & Usup (Reference Sneddon and Usup1986: 414–415) draw attention to similar phenomena in the Gorontalic languages of northern Sulawesi. Their data sample in Table IV shows reflexes of Proto-Malayo-Polynesian *a after a voiced stop.

Table IV Reflexes of Proto-Malayo-Polynesian *a after a voiced stop.

In addition, they state (1986: 414) that Proto-Gorontalic ‘*o became u following a voiced stop. This change occurred in all languages except Bnt [Bintauna] but was not entirely regular in any language.’

For ready reference, these changes are summarised under (17), where rare reflexes appear in parentheses, and alternatives of roughly equal frequency are separated by ‘/’ (nearly all changes in the Gorontalic languages can apparently be captured by developments in Gorontalo and Buol).

(17)

As can be seen, most languages for which this type of change has been reported favour a front vowel outcome, but outside the North Sarawak group, where this is the only attested outcome, about half of all languages show raising of *a to a central or back vowel. Given this broader perspective, the changes that have previously been subsumed under the label LVF can now be stated as a special case of low vowel raising. Most importantly, once we change our perspective in this way, certain other observations acquire a significance they previously did not have.

8 The clinching argument

For Casiguran Dumagat, Healey (Reference Healey, Headland and Headland1974) not only describes low vowel raising, but also observes that in the final syllable high vowels lower to e and o if the immediately preceding consonant is not a voiced stop (18a), but remain unchanged after a voiced stop (18b).

(18)

Likewise, as shown above, Sneddon & Usup (Reference Sneddon and Usup1986) found that a mid-back vowel from any source often raises to /u/ when following a voiced obstruent in Buol and some other Gorontalic languages of northern Sulawesi. Although it might not be immediately obvious, these changes share the same complex conditioning as Miri, as shown in (19) for Casiguran Dumagat, where the first column gives the default reflexes, and the second gives reflexes if there is a voiced obstruent earlier in the word.

(19)

There is a previously overlooked unity to these changes: regardless of differences in other details of their history, every language raises *a after a preceding voiced obstruent, and in several of them a high vowel which would otherwise lower remains high under the same condition. In Casiguran Dumagat vowel lowering is straightforward, while in Miri it takes two forms: *i/u > e/o before certain consonants, and *i/u > ai/au, aj/aw before other consonants, or word-finally. This was initially a distraction, since vowel breaking in Miri appeared to be a variation on the common patterns in Table I, but the larger constellation of changes affecting final-syllable vowels in this language shows that what has previously been called ‘low vowel fronting’ is actually low vowel raising, and what initially appeared to be high vowel breaking is actually high vowel lowering. That *i/u > aj/aw is essentially a lowering process is clear because breaking and lowering are in complementary distribution, as shown in §4.3.Footnote 13

9 Conclusion

What at first appears to be an arbitrary condition in Miri (and other languages) turns out on further analysis to be a product of favoured phonetic outcomes that are driven by inherent airflow conflicts in voiced obstruents: the blocking of an egressive airstream raises air pressure above the glottis, which lowers the larynx, and so lengthens the pharyngeal cavity. Since the first formant is a back cavity resonance, and the primary acoustic correlate of vowel height, it favours the perception of following vowels as higher than their default values, either by raising a low vowel or suppressing the lowering of a high vowel. In Miri, this process is obscured by vowel breaking in certain environments, but this can be seen as a type of lowering, as it appears to be in other languages.

Finally, while the proposal advanced here helps to explain a challenging sound change, it does not succeed in eliminating all odd conditions. Among those that remain unexplained are: (i) why do some languages (such as Miri or Sa'ban) have blocking consonants, while others that may be closely related (such as Narum) do not?; (ii) why in Miri (but not in most other languages) does low vowel raising skip over a closer target to affect one in the final syllable?; (iii) why does Miri use vowel breaking as a surrogate for lowering in word-final position, before a final glottal stop, and only with *i (but not *u) before final coronals? And, to extend the questions beyond Miri: (iv) why, in Gorontalo, does an otherwise general process of low vowel raising to /e/ produce /o/ when the vowel of the next syllable is high (whether it is back or front)?; (v) why in Manide does *a raise to /e/ after a voiced obstruent in the first syllable, but to /u/ under the same condition in the last syllable?; and (vi) why in Manide do back vowels front after a voiced obstruent? (Lobel Reference Lobel2010: 491).

Questions like these remind us that, despite our successes in some areas of phonology, many other areas resist phonetic explanation, and will no doubt continue to challenge linguists for years to come.