1 Introduction

Homophony avoidance is one of a series of phenomena in which the well-formedness of each form is evaluated with respect to all contrasts in a system (Padget Reference Padgett2003). Contrast-based frameworks include Dispersion Theory in phonetics (Ní Chiosáin & Padgett Reference Ní Chiosáin, Padgett and Parker2010, Flemming Reference Flemming and Aronoff2017) and Preserve Contrast Theory in phonology (Riggs Reference Riggs, Colavin, Cooke, Davidson, Fukuda and Guidice2007, Łubowicz Reference Łubowicz2012, Reference Łubowicz2016). Contrast preservation has also been posited in diachronic linguistics in the functional load hypothesis (Martinet Reference Martinet1955), as well as taboo replacement (Baerman Reference Baerman2010, Campbell Reference Campbell2013). Homophony avoidance in particular has most often been employed to account for otherwise exceptional phonological and morphophonological processes, such as the blocking of regular sound change in Trigrad Bulgarian (Crosswhite Reference Crosswhite1999), Russian (Crosswhite Reference Crosswhite1999) and Teiwa (Baerman Reference Baerman2010), sporadic changes in Dalkelh (Gessner & Hansson Reference Gessner and Hansson2004), Russian and Belarusian (Bethin Reference Bethin2012) and defective morphological paradigms in Mazatec, Tamashek and Icelandic (Baerman Reference Baerman2010). However, it is not clear if homophony avoidance constitutes a synchronic restriction in the grammar of the speaker or, as has been argued (Blevins & Wedel Reference Blevins and Wedel2009, Mondon Reference Mondon2010), an emergent diachronic development born of imperfect transmission.

This paper attempts to fill the gap found in the literature by discussing a correlation between stress pattern and allomorph choice in Russian masculine nominals. I show that the patterns observed in the language can be ascribed to a combination of homophony avoidance and another restriction, namely paradigm uniformity. A nonce-word task was constructed so as to limit the effects of paradigm uniformity, therefore testing homophony avoidance exclusively. Results confirm not only that the restriction found in Russian masculine nominals is productive, but that synchronic homophony avoidance is the most likely explanation for this phenomenon.

The Russian data discussed in this paper is similar to the example of homophony avoidance in Trigrad Bulgarian (Crosswhite Reference Crosswhite1999, based on data from Stojkov Reference Stojkov1963), which I summarise below. In the Trigrad dialect of Bulgarian, vowel reduction and stress conspire to preserve contrast within the morphological paradigm. An illustration of the vowel-reduction process is given in (1). In unstressed position, the mid back vowels /o/ and /ɔ/ merge with /a/, while /ɛ/ merges with /e/.

-

(1)

The reduction can be observed in stems where stress shifts due to suffixation, as in (2), where the full vowels in the stem of the indefinite contrast with the reduced vowels in the definite. Note that the neuter suffix /-o/ also undergoes reduction in the indefinite form.

-

(2)

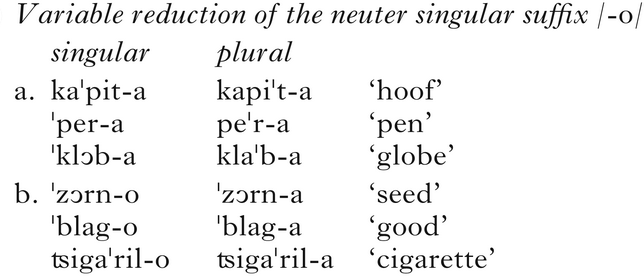

However, vowel reduction fails to apply in certain morphological environments. Of particular interest is the neuter singular suffix /-o/, which reduces to /a/ in some stems, as in (3a), but not others, as in (3b). Whether the suffix reduces in a given stem is not predictable from the neuter singular form alone.

-

(3)

Crosswhite (Reference Crosswhite1999) demonstrates that the vowel reduction in the neuter singular suffix is entirely predictable if the plural form is taken into consideration. The neuter plural marker in Trigrad Bulgarian is underlyingly /-a/. Because unstressed /o/ is realised as /a/, vowel reduction has the potential to create homophonous singular ~ plural pairs.

However, no homophonous singular ~ plural pairs are found in the dialect. In (3a), where the singular and plural forms differ in stress placement, vowel reduction applies normally and does not produce homophony. In (3b), where the singular and plural match in stress placement, vowel reduction fails to apply. In other words, the singular is always disambiguated from the plural, either prosodically or segmentally. The application of vowel reduction, which appears sporadic when looking at a single form, is entirely predictable when the paradigm is taken into account. Crosswhite (Reference Crosswhite1999) argues that the blocking of vowel reduction in Trigrad Bulgarian is best described synchronically, and models the phenomenon in Optimality Theory. However, Mondon (Reference Mondon2009) gives an entirely diachronic account, arguing that the data can just as easily be explained by competing grammars, one with reduction and one without, merging over time in a way that increases communicability.

In fact, it has been argued that all instances of homophony avoidance can be explained diachronically (Kroch Reference Kroch, Fasold and Schiffrin1989, Labov Reference Labov1994, Mondon Reference Mondon2010). A completely contrastive production of a target word is likely to contribute to the mental representation of the target, whereas a production that is homophonous with a competitor is likely to contribute to the mental representation of the competitor rather than the intended target. Over time, this results in the gradual divergence of mental representations, a claim that is supported by computational models (Blevins & Wedel Reference Blevins and Wedel2009, Winter & Wedel Reference Winter and Wedel2016). An emergent gradual divergence such as this removes the need to posit an active anti-homophony restriction in the grammar. Instead, homophony avoidance can be achieved through errors in transmission and language learning. Artificial language learning paradigms have found a learning bias compatible with this framework (Yin & White Reference Yin and White2018). More generally, in any evolutionary framework, multiple entities occupying the same niche tend to be unstable and diverge over time, a trend that has also been observed outside of linguistics, for example in biology (see Pocheville Reference Pocheville, Heams, Huneman, Lecointre and Silberstein2014 for an overview of the ‘competitive exclusion principle’).

It is often assumed that a synchronic restriction against homophony is not sufficiently motivated (King Reference King1967, Mondon Reference Mondon2009, Paster Reference Paster2010, Sampson Reference Sampson2013). However, there are few experimental studies that have broached the subject. One exception is Ichimura (Reference Ichimura2006), which presents a production experiment performed on Japanese verbs. Results from the experiment suggest that speakers are less likely to apply an optional nasal assimilation process when this results in homophony with a competing word. However, it has been subsequently claimed that the results are best analysed as positional faithfulness rather than homophony avoidance (Kaplan & Muratani Reference Kaplan and Muratani2015). It is still a matter of debate whether examples of synchronic restrictions on homophony exist.

This paper presents experimental and corpus data from Russian in evidence of a synchronic restriction against homophony. In §2, I provide the necessary background on Russian phonology and nominal morphology. Specifically, I focus on two sets of allomorphs in the masculine nominal paradigm. One member of each set is potentially homophonous with another. In §3, I describe a corpus study, in which I find that the selected allomorphs hardly ever produce homophonous pairs in the paradigm. Similarly to the Trigrad Bulgarian example in (3), allomorphy conspires with stress to ensure contrast within the paradigm. I therefore claim that this pattern is indicative of homophony avoidance in the language. In §4, I describe a nonce-word perception experiment, which was conducted exploiting the potential homophony caused by allomorph selection. The results of the experiment indicate that the prosodic disambiguation strategy is productive. Finally, in the discussion in §5, I show that the results are not compatible with a simple projection of lexicon trends, and are best analysed as a homophony restriction encoded in the synchronic grammar.

2 Russian stress paradigms

Russian has a free lexical stress system. Stress can be assigned to any syllable within the stem, e.g. [ˈzagovor-amʲi] ‘with the conspiracies’ and [ugoˈvor-amʲi] ‘with the persuasions’, as well as to the first syllable of the inflectional suffix, as in [dogovoˈr-amʲi] ‘with the agreements’.

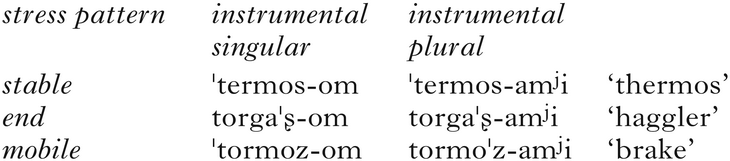

In the nominal paradigm, stress generally remains consistent within the same grammatical number, singular or plural, but not necessarily between the two. For those masculine nouns where stress is inconsistent, it is usually the case that the singular bears stem stress, while the plural bears suffix stress. Therefore, there are three general stress patterns; I outline these in (4), using Coats’ (Reference Coats1976) terminology. The singular and plural instrumental forms are given as examples; stress placement in other cases matches the example of the same grammatical number.

-

(4)

Nouns with a stable pattern have stem stress in both the singular and plural. Nouns with an end pattern have suffix stress in both the singular and plural. Nouns with a mobile pattern have stem stress in the singular but suffix stress in the plural.

Other stress patterns do exist, including suffix stress in the singular and stem stress in the plural, as well as many exceptional patterns with variable stress within grammatical number. However, as will be shown in §3, the patterns in (4) comprise more than 99% of masculine nouns. Because the other stress patterns are rare and not relevant here, they will not be discussed further.

Russian nominals possess a rich inflectional system, with suffixes corresponding to combinations of gender, number and case. The inflectional suffixes for Russian masculine nominals can be seen in (5), with the more commonly occurring allomorph listed first. Where more than one exponent is listed, the suffix shape is conditioned lexically, and is not predictable from the stem, as in the nominative singular and nominative plural forms in [ˈtom] ~ [toˈm-a] ‘volume’ and [ˈatom] ~ [ˈatom-i] ‘atom’.Footnote 1

-

(5)

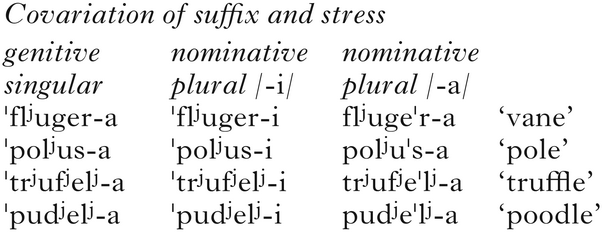

Note that some of the less common (secondary) allomorphs are potentially homophonous with other forms in the paradigm. For example, the secondary nominative plural marker /-a/ is identical to the genitive singular. Likewise, the secondary prepositional and genitive markers, both /-u/, are potentially homophonous with the dative singular. In the remainder of this paper, I will argue that the distribution of two of these potentially homophonous allomorphs, namely nominative plural /-a/ and prepositional singular /-u/, is conditioned by homophony avoidance.

The /-a/ allomorph of the nominative plural will be addressed in §3.1. Most Russian masculine nouns take the nominative plural suffix /-i/, which is also found in related Slavic languages, e.g. Slovak [ˈxleb-i] ‘breads’. However, it appears that during the fifteenth century a new nominative plural suffix /-a/ began to be diffused in the language, e.g. Modern Russian [xlʲeˈb-a] ‘breads’. This allomorph attached only to a handful of nouns at first, but has been spreading to more and more stems ever since (Yanovich Reference Yanovich1986). The origins of this suffix are complex. The old nominative dual, which was already on the decline at the time (Shakhmatov Reference Shakhmatov1957, Yanovich Reference Yanovich1986, Timberlake Reference Timberlake2004), was also /-a/, and a number of semantically paired nouns preserve the original dual /-a/, now reanalysed as a plural marker, such as [roˈg-a] ‘horns’ and [bʲerʲeˈg-a] ‘banks (of a river)’. Once the plural/dual distinction was lost, the suffix also began to be applied to nouns that are not semantically paired, such as [goroˈd-a] ‘cities’ and [goloˈs-a] ‘voices’. The spread of the /-a/ nominative plural may have been reinforced by the fact that neuter nouns take /-a/ as a plural suffix; this is especially crucial because the morphological gender distinction in the plural had already begun to break down (Yanovich Reference Yanovich1986). Although the proliferation of the new allomorph had been steady since the late Middle Ages, it seems to have slowed down in the twentieth century. Nowadays, its use is somewhat more restricted in standard speech than in some non-standard varieties (Krysin Reference Krysin1974).

The prepositional singular /-u/ allomorph will be addressed in §3.2. Most Russian masculine nouns take the prepositional singular suffix /-ʲe/. However, a handful of nouns have /-u/, but only when governed by the prepositions /v/ ‘in’ and /na/ ‘on’. After /o/ ‘about’, /po/ ‘on top of’ and /prʲi/ ‘by’, all of which require the prepositional case, the more widespread /-ʲe/ suffix must be used instead (Timberlake Reference Timberlake2004). Thus, the stems /lʲes/ ‘forest’ and /gorod/ ‘city’ take different suffixes in [v lʲeˈs-u] ‘in the forest’ and [ˈv gorod-ʲe] ‘in the city’, but the same suffix in [o ˈles-ʲe] ‘about the forest’ and [o ˈgorod-ʲe] ‘about the city’. Historically, the two prepositional singular suffixes existed in different inflectional paradigms (Yanovich Reference Yanovich1986). As the paradigms began to merge, /-ʲe/ became dominant, and words with the /-u/ prepositional singular decreased in number. In modern Russian, the use of /-u/ appears to be limited, but stable (Krysin Reference Krysin1974).

Finally, something must be said about the /-u/ genitive singular. Like the /-u/ prepositional singular, this suffix is restricted both lexically and semantically. The /-u/ genitive singular appears only in a handful of nouns, mainly in partitive or partitive-like constructions (Timberlake Reference Timberlake2004). However, unlike the prepositional singular /-u/, the genitive singular can always be replaced by the more widespread allomorph /-a/, but not vice versa (Timberlake Reference Timberlake2004). For example, the stem /saxar/ ‘sugar’ can optionally take either suffix in [nʲeˈmnogo ˈsaxar-u] or [nʲeˈmnogo ˈsaxar-a] ‘a little sugar’, but only the more common allomorph in [ˈʦvʲet ˈsaxar-a] ‘colour of sugar’ (*[ˈʦvʲet ˈsaxar-u]). Akin to the allomorphy in the prepositional singular, the two genitive singular suffixes also originated from different inflectional paradigms. The partitive nature of the /-u/ variant is sometimes attributed to a few salient nouns, such as /mʲod/ ‘honey’, /vosk/ ‘wax’ and /xmʲelʲ/ ‘hops’, which both took the /-u/ genitive singular and were partial to partitive constructions (Yanovich Reference Yanovich1986). In modern Russian, it appears that the /-u/ genitive singular is on the decline, particularly in the younger generation (Krysin Reference Krysin1974).

It should be noted that, unlike the other two potentially homophonous suffixes, homophony with the /-u/ genitive singular is not avoided. In fact, the /-u/ genitive singular is always homophonous with the dative singular, e.g. [ˈsaxar-u] ‘sugar (dat.sg/gen.sg)’. It is unclear why the /-u/ genitive singular behaves differently from the /-u/ prepositional singular and the /-a/ nominative plural. The fact that it can always be replaced by the more common /-a/ may play a role in the explanation, but it is impossible to say conclusively. Because this analysis cannot be extended to the /-u/ genitive singular, it will not be discussed any further in this paper.

With respect to stress and its distribution in the other two instances of allomorphy, two patterns are conceivable. On the one hand, if the choice of suffix and stress pattern is entirely independent, the homophonous suffixes are expected to yield homophonous forms for at least some of the words. On the other, if, just as in Trigrad Bulgarian, Russian uses stress to disambiguate homophonous forms within the paradigm, suffix choice and stress pattern are expected to conspire to avoid homophony. In the following section, I present a case study demonstrating that the latter holds true.

3 Corpus study

3.1 Method

To acquire a word-list of common Russian nouns, data was taken from the General internet corpus of Russian (Belikov et al. Reference Belikov, Kopylov, Piperski, Selegey and Sharoff2013, Piperski et al. Reference Piperski, Belikov, Kopylov, Morozov, Selegey, Sharoff, Evert, Stemle and Rayson2013), henceforth GICR. The corpus is wholly orthographic, and comprises some two million words, collected from Russian social media. All words in the corpus are morphologically parsed for gender, case and number. Masculine nouns were extracted from the corpus and filtered manually. Proper nouns, abbreviations and indeclinable loans were removed, as were pluralia tantum, de-adjectival nouns and masculine nouns that take feminine morphology. To reduce the number of foreign words and spurious coinages, only nouns appearing at least twice in the GICR were retained. A total of 4230 masculine nouns fitted these criteria.

As stress is not normally indicated in Russian orthography, the stress pattern for each entry was subsequently added manually by the author of this paper. GICR was thus merely used to obtain a list of common Russian nouns, whereas the stress marking reflects the intuitions of the author. Because there exists some between-speaker variation in Russian accentuation (Sharapova Reference Sharapova2000, Lagerberg Reference Lagerberg2011), Shtudiner (Reference Shtudiner2016), a specialised dictionary developed to document the stress pattern of unusual or obscure Russian words, was consulted in all but the straightforward cases. Straightforward cases (84.9%) were defined as those with stable stress and the common nominative plural and prepositional singular allomorphs. It is unlikely that the author's personal bias had a significant effect on the results. However, if any bias is present, it is manifested as a slight overrepresentation of stable stress, as well as the /-i/ nominative plural and /-ʲe/ prepositional singular allomorphs, something which is unlikely to affect the analysis.

Occasionally, the dictionary listed several stress patterns as optional variants; in such cases, a separate entry for each stress pattern was made. All in all, there were 120 (2.8%) entries with more than one stress pattern. For a breakdown of masculine nouns by stress pattern, see Table I.

Table I Masculine nouns by stress pattern.

The overwhelming majority of masculine nouns have a stable stress pattern, with stress on the same syllable in the stem in both the singular and plural. 10.9% have an end stress pattern, with stress on the first syllable of the inflectional suffix in both the singular and plural. A small number of masculine nouns have a mobile stress pattern, with stress on a syllable in the stem in the singular and on the suffix in the plural. As mentioned above, other stress patterns are rare, comprising less than 1% of the corpus.

3.2 Results

3.2.1 Nominative plural ~ genitive singular homophony

Recall that the nominative plural for Russian masculine nouns can be signalled by one of two suffixes, /-i/ or /-a/, the latter of which is homophonous with the genitive singular suffix. The choice of suffix is lexical. For the distribution of stress pattern with regard to suffix, see Table II.

Table II Masculine nouns by stress pattern and nominative plural allomorph.

Masculine nouns that take the nominative plural /-i/ allomorph are overwhelmingly more common, comprising 97.5% of the data. Nouns with the /-a/ allomorph are rare, and their distribution in terms of stress pattern differs radically from the norm: mobile stress is most common, followed by stable stress and finally by end stress.

Of the 105 nouns that take the /-a/ nominative plural suffix, 69.5% exhibit mobile stress. In the remainder of the language, mobile stress is extremely rare, occurring in around 1.3% of words. The trend for the nominative plural /-a/ allomorph to co-occur with mobile stress has been noted previously (Coats Reference Coats1976, Zaliznjak Reference Zaliznjak1985, Timberlake Reference Timberlake2004, Lagerberg Reference Lagerberg2011); while the link to homophony avoidance has not been made, it has been hypothesised that the mobile stress pattern helps increase contrast between singular and plural forms in general (Alderete Reference Alderete2001).

Homophony avoidance offers an explanation for the asymmetry: a mobile stress pattern preserves the distinction between singular and plural forms that take homophonous suffixes, as shown in (6). Stress is assigned to the stem in the genitive singular and to the suffix in the nominative plural. The potentially homophonous forms are disambiguated prosodically.

-

(6)

Table II showed that a number of nouns that take the /-a/ nominative plural suffix do not exhibit a mobile stress pattern. However, these nouns also display homophony avoidance, not prosodically but morphologically. All 28 nouns that take the /-a/ nominative plural and exhibit a stable stress pattern have a suppleted plural stem, as shown in (7).Footnote 2 These nouns are exceptional, in that their singular stem is different from their plural stem.

-

(7)

Observe that in (7) the genitive singular and nominative plural display different, though historically related, stems. The alterations in the stems, such as the appearance of stem-final [j] in the nominative plural of ‘brother’, ‘scab’ and ‘tuft’, are not synchronically active in Russian, and are limited to these and a handful of other nouns. The potentially homophonous forms in (7) are disambiguated morphologically.

In the corpus, there is only one true exception to the nominative plural ~ genitive singular homophony avoidance generalisation. The word /rukav/ ‘sleeve’ takes the /-a/ nominative plural, and exhibits an end stress pattern without stem suppletion. The genitive singular and nominative plural for this word share the form [rukaˈv-a]. This particular noun is probably aberrant because, due to its semantically paired nature, it is one of the few that had the /-a/ ending originally, rather than as a result of the subsequent spreading (Yanovich Reference Yanovich1986).

For completeness, it should also be mentioned that, for the three nouns that take the /-a/ nominative plural suffix but do not conform to any of the three main stress patterns (‘other’ in Table II), the nominative plural and genitive singular are not homophonous. Therefore, for all but one of the masculine nouns in the corpus, the nominative plural ~ genitive singular pair of suffixes, despite being potentially homophonous, fails to produce homophonous forms. For words with identical singular and plural stems, as in (6), stress is mobile, and the forms are disambiguated prosodically. For words with a stable stress pattern, as in (7), the forms are disambiguated morphologically. The generalisation is extremely robust, and a χ 2 test for independence performed on stress pattern and nominative plural suffix shows that the two are not independent (p < 0.0001, df = 3, χ 2=1633).

Further evidence of the same homophony avoidance pattern comes from words that, according to Shtudiner (Reference Shtudiner2016), can take either nominative plural suffix, as in (8). In all of these words, the potentially homophonous /-a/ suffix is coupled with suffix stress on the nominative plural, and the non-homophonous /-i/ suffix with stem stress. Contrast between the genitive singular and the nominative plural is always preserved: if the genitive singular matches the stress of the nominative plural, the two will differ in the suffix; if the genitive singular matches the suffix of the nominative plural, the two will differ in stress.

-

(8)

Note that Shtudiner (Reference Shtudiner2016) occasionally lists different stress patterns for different meanings. For example, /lagerʲ/ ‘camp’ is listed with stable stress when referring to a political camp ([ˈlagerʲ-i] (nom.pl)), but with mobile stress when referring to a military camp ([lageˈrʲ-a] (nom.pl)). Likewise, /uʨitʲelʲ/ ‘teacher’ is listed with stable stress when referring to the founder of a doctrine ([uˈʨitʲelʲ-i] (nom.pl)), but with mobile stress when referring to an educator ([uʨitʲeˈlʲ-a] (nom.pl)). Here too, the nominative plural /-a/ suffix co-occurs with mobile stress, while the /-i/ nominative plural suffix co-occurs with stable stress.

Finally, evidence of homophony avoidance comes from diachrony. As previously mentioned, many words have switched from the /-i/ nominative plural to the /-a/ nominative plural. These changes are historically always accompanied by a change from a stable to a mobile stress pattern, cf. modern Russian [toˈm-a] ‘volumes’ and 19th-century [ˈtom-i].Footnote 3

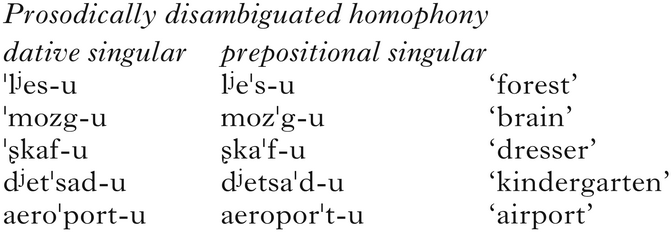

3.2.2 Prepositional singular ~ dative singular homophony

Similar to the nominative plural, the prepositional singular for Russian nouns can be realised with one of two suffixes, /-ʲe/ or /-u/, the latter of which is homophonous with the dative singular. /-u/, but not /-ʲe/, violates the generalisations presented in §2. Regardless of the stress pattern, the prepositional singular /-u/ suffix is always stressed (Fedianina Reference Fedianina1982), a property that can be traced as far back as Proto-Balto-Slavic (Shakhmatov Reference Shakhmatov1957). See, for example, the declension of /lʲes/ ‘forest’ in (9). This word exhibits mobile stress: all forms in the plural bear suffix stress, and all forms in the singular bear stem stress. The one exception is the prepositional singular, which bears stress on the suffix. Note that nouns that take the /-u/ prepositional singular were not counted as exceptional in the corpus study if all other forms conformed to one of the three stress patterns in (4).

-

(9)

As in nominative plural ~ genitive singular homophony avoidance, the stress pattern of the word determines whether the dative singular and the prepositional singular are homophonous. Because both potentially homophonous forms are singular, the plural forms are not relevant. The dative singular and prepositional singular are homophonous if the singular bears suffix stress. Therefore, homophony between the dative and prepositional /-u/ occurs in the end stress pattern. Table III gives the distribution of stress pattern with regard to suffix.

Table III Masculine nouns by stress pattern and prepositional singular allomorph.

Masculine nouns that take the /-ʲe/ prepositional singular allomorph are overwhelmingly more common, comprising 98.3% of the data. Nouns that take the /-u/ allomorph are not only rare, but their distribution in terms of stress pattern differs from the norm: mobile stress is most common, followed by stable stress and finally by end stress and other stress patterns.

Of the 73 nouns that take the prepositional singular /-u/ suffix, a smaller proportion exhibit an end stress pattern than either mobile or stable stress. In the remainder of the language, end stress is the second most common pattern. Homophony avoidance is a tempting explanation for this asymmetry. Stable and mobile stress patterns preserve contrast between the dative singular and the exceptional prepositional singular forms, as in (10). Stress is assigned to the stem in all singular forms except for the prepositional, and the potentially homophonous forms are disambiguated prosodically.

-

(10)

While a stable or mobile stress pattern maintains contrast between the prepositional and dative singular, Table III shows that a minority of nouns that take the /-u/ prepositional suffix do not exhibit either of these patterns. The seven end-stressed nouns constitute genuine exceptions to the generalisation: [moˈst-u] ‘bridge (dat.sg/prep.sg)’, [plaˈst-u] ‘stratum (dat.sg/prep.sg)’, [ploˈt-u] ‘raft (dat.sg/prep.sg)’, [polˈk-u] ‘platoon (dat.sg/prep.sg)’ and [pruˈd-u] ‘pond (dat.sg/prep.sg)’, and the diminutives [luʐˈk-u] ‘little meadow (dat.sg/prep.sg)’ and [puˈʂk-u] ‘little fluff (dat.sg/prep.sg)’. Additionally, three irregularly stressed nouns display the same stress assignment on the prepositional and dative singulars: [uˈgl-u] ‘corner (dat.sg/prep.sg)’, [koˈl-u] ‘stake (dat.sg/prep.sg)’ and [suˈk-u] ‘bough (dat.sg/prep.sg)’. Finally, like all Slavic languages, Russian exhibits vowel ~ zero alternations in some stems, due to the loss of the so-called yer vowels (Gouskova & Becker Reference Gouskova and Becker2013). This occasionally results in stems without an underlying vowel, to which no stress pattern can be assigned (these are also listed under ‘other’). Four vowelless masculine nouns take the /-u/ prepositional suffix and also constitute exceptions to our generalisation: [ˈlʲd-u] ‘ice (dat.sg/prep.sg)’, [ˈlʲn-u] ‘flax (dat.sg/prep.sg)’, [ˈlb-u] ‘forehead (dat.sg/prep.sg)’ and [ˈmx-u] ‘moss (dat.sg/prep.sg)’. All in all, then, there are 14 exceptions to the prepositional singular ~ dative singular homophony avoidance generalisation.

This generalisation is not as robust as the nominative plural ~ genitive singular homophony avoidance in §3.1. Nevertheless, a χ 2 test for independence performed on stress pattern and nominative plural suffix shows that the two are not independent (p < 0.0001, df = 3, χ 2 = 976). Indeed, for 59 out of 73 nouns, the potentially homophonous /-u/ suffix does not produce homophony in the paradigm.

In fact, it is surprising that the prepositional singular and dative singular are disambiguated at all. Unlike nominative plural ~ genitive singular homophony avoidance, none of the regular stress patterns in §2 can disambiguate two singular forms prosodically. It is the exceptional nature of the /-u/ prepositional singular suffix, i.e. the fact that it bears stress regardless of overall stress pattern, that allows disambiguation through prosody. As will be shown in the following section, this exceptional property can also be modelled as homophony avoidance.

3.3 Discussion

The two pairs of Russian homophonous suffixes discussed in this section produce very few homophonous forms in their paradigms. Often forms that carry the same inflectional suffix are distinguished prosodically: one of the homophonous suffixes bears stress, while the other does not. In situations with identical suffixes and identical stress assignment, one of the forms usually carries a suppleted stem. The nominative plural ~ genitive singular homophonous pair of suffixes yields only a single counterexample to this generalisation. The prepositional singular ~ dative singular pair is less robust, with fourteen counterexamples.

To account for the correlation of stress pattern and suffix, this paper pursues the idea that the language displays a bias towards contrast preservation within the morphological paradigm. Ceteris paribus, the choice of allomorph, stress pattern and stem should not result in two forms with different underlying morphology and identical surface representation. More specifically, I assume that, just as in Trigrad Bulgarian, stress, and not some other repair mechanism, is used to disambiguate potentially homophonous forms. Homophony avoidance will be modelled using the Optimality Theory framework (Prince & Smolensky Reference Prince and Smolensky2004).

Note that, given the results of the corpus study, markedness and faithfulness constraints alone cannot determine the winning candidate. Grammaticality in Russian masculine nominals must be influenced by other forms in the paradigm. Therefore, the OT framework employed must be able to generate a comparison set, members of which are compared to each candidate in the tableaux. There are many examples of such frameworks in the literature (e.g. Steriade Reference Steriade, Broe and Pierrehumbert2000, Alderete Reference Alderete2001, Padgett Reference Padgett2003, Łubowicz Reference Łubowicz2012).

This paper will follow the approach in Crosswhite (Reference Crosswhite1999), which models the interaction of vowel reduction, stress shift and homophony avoidance in Trigrad Bulgarian. Central to the data is the constraint Anti-Ident, adapted from Crosswhite and defined in (11), which assigns a violation for every form in the comparison set that does not differ from the candidate in some phonological property, be it segmental or prosodic. Anti-Ident is very similar to Anti-Faithfulness (Alderete Reference Alderete2001), which is a constraint that encourages dissimilarity between a candidate and the underlying form or a selected base form. In principle, Anti-Faithfulness is able to model homophony avoidance, but only if the homophonous competitor is pre-selected as the base form. Anti-Ident penalises homophony directly, and is therefore the more natural choice here.

-

(11)

Following Ní Chiosáin & Padgett (Reference Ní Chiosáin, Padgett and Parker2010), this paper makes use of comparison sets, i.e. subsets of the lexicon relevant for comparison. Based on the results from the corpus study as well as previous findings (Baerman Reference Baerman2010, Bethin Reference Bethin2012, Kaplan & Muratani Reference Kaplan and Muratani2015, Pertsova Reference Pertsova2015), the domain of homophony avoidance, and therefore the comparison set, appears to be the morphological paradigm. However, note that evidence in favour of broader, between-word homophony avoidance effects exists as well (Silverman Reference Silverman2009, Ogura & Wang Reference Ogura, Wang, Cluskey, Flaherty, Little, McCrohon, Ravignani and Verhoed2018). For the purposes of this study, the comparison set will be limited to all forms in the morphological paradigm of the input. In fact, it will be limited further in §4.2.2 to exclude forms in the morphological paradigm not familiar to the speaker. For now, since it can be assumed that the speaker is acquainted with the entire paradigm of the input, homophony between any forms in the paradigm is in violation of Anti-Ident. Therefore, to evaluate a tableau, every candidate must be compared with every form in the morphological paradigm. For Russian nominals, this means eleven comparisons per candidate (six grammatical cases × two grammatical numbers, minus one since there is no point in comparing a form to itself). However, for the purposes of exposition, only members of the comparison set that can influence the result of the derivation will be listed.

A second constraint is required to explain the data. This is ParadigmUniformity (PU), defined in (12) (adapted from Steriade Reference Steriade, Broe and Pierrehumbert2000). Paradigm uniformity is the well-established preference for an underlying morpheme to have identical exponents (Kiparsky Reference Kiparsky1982: ch. 11, Steriade Reference Steriade, Broe and Pierrehumbert2000, Do Reference Do2018). This constraint assigns a violation for every form in the comparison set that shares a morpheme with the candidate but not its surface realisation. I set the scope of this constraint to ‘all’, indicating that comparisons are with the entire comparison set, i.e. the entire morphological paradigm. Adjusting the scope of the PU constraint will be crucial later in the analysis.

-

(12)

In (13), we can see how a stress shift is motivated for the nominative plural of the mobile-stressed word /tom/ ‘volume’, which takes the /-a/ suffix. To ensure that homophony avoidance takes place, Anti-Ident outranks PUall. For clarity, the comparison set is listed alongside every tableau, rather than separately, as is done in Crosswhite (Reference Crosswhite1999). Once again, I assume that the comparison set contains all eleven other members of the /tom/ morphological paradigm. However, because we know that only the genitive singular can be homophonous, it is the only form included here.

-

(13)

In the tableau, stem-stressed candidate (a) maintains paradigm uniformity, as it shares the exponent of the root /tom/ with a member of the comparison set. However, by the same token, it violates Anti-Ident, since it is phonologically but not syntactically identical to the member of the comparison set. On the other hand, (b), the suffix-stressed candidate, violates PUall but not Anti-Ident. Because Anti-Ident is ranked higher than PUall, candidate (b) wins, and contrast is maintained.

It is important to note that the accentual relation between the nominative plural and genitive singular is symmetric. (13) derives suffix stress in the nominative plural based on stem stress in the genitive singular in the comparison set. One could just as easily derive stem stress in the genitive singular based on suffix stress in the nominative plural. In fact, anti-homophony and paradigm uniformity can only define relations between morphologically related forms; they cannot evaluate a single candidate in isolation.

I assume that stress assignment for the form in the comparison set is either derived by constraints not relevant to this project or is simply underlying. Likewise, it is assumed that contrast is not expressed through segmental means, such as deletion or epenthesis, because of high-ranked faithfulness constraints such as Max or Dep. The purpose of this section is not to offer a full account of the phonology of Russian stress, but simply to model its interaction with homophony avoidance. For theoretical descriptions of Russian accentuation, see Idsardi (Reference Idsardi1992), Alderete (Reference Alderete2001) and Osadcha (Reference Osadcha2019).

Recall that stress assignment in the nominative plural and genitive singular can match if the plural forms exhibit stem suppletion. This pattern is readily modelled with the same constraints. Consider the exceptional stem /kom/ ‘lump’ in (14). While the genitive singular of this stem [ˈkom-a] is perfectly regular, the plural forms exhibit an additional and irregular [j], as in nominative [ˈkomj-a].Footnote 4

-

(14)

Unlike in (13), the stem-stressed candidate, (a), does not violate Anti-Ident with the genitive singular (or any other form) in the comparison set. Suffix-stressed candidate (b) violates PUall, which was tolerated in (13), but not in (14). As a result, (a) is the winner, and the word exhibits a stable stress pattern.

The two constraints employed, Anti-Ident and PUall, account for the difference in stress assignment between the genitive singular and nominative plural. For the rest of the paradigm, an additional constraint is necessary. Grammatical cases other than the genitive singular and nominative plural are unaffected by the Anti-Ident constraint, due to the lack of corresponding homophonous suffixes. Furthermore, PUall cannot choose a winning candidate, as there may be both stem-stressed and suffix-stressed forms in the comparison set. Without further constraints, it is unclear how stress would be assigned in, say, the prepositional plural, which would violate PUall through comparison to the nominative plural if it is stem-stressed and through comparison to the genitive singular if it is suffix-stressed.

Recall that stress in Russian is generally consistent within grammatical number, but not necessarily between singular and plural. I will use this as evidence for a narrower paradigm uniformity constraint, PUnum, defined in (15). In essence, this is the same constraint as in (12), but with only forms of matching grammatical number taken into account. The assumption that Russian nouns have separate singular and plural inflectional bases is not exclusive to this paper; it has been made previously by Zaliznjak (Reference Zaliznjak1985), Alderete (Reference Alderete2001) and Pertsova (Reference Pertsova2015).

-

(15)

In (16), we can see how a stress shift is motivated by this new constraint for the prepositional plural of the same word /tom/. For simplicity, only the genitive singular and nominative plural forms are included in the comparison set, as adding other forms would not affect the outcome. Neither candidate violates Anti-Ident. Both candidates violate PUall, but, because PUnum only cares about comparisons with other plural forms, it is violated by stem-stressed candidate (a), but not by suffix-stressed (b). Therefore, (b) is correctly chosen as the winner.

-

(16)

For completeness, in (17) I model the prepositional singular ~ dative singular homophony avoidance using OT. No new constraints are required. The word /lʲes/, which takes the prepositional singular /-u/ suffix, is used as an example. For simplicity, only the competing dative singular form is included in the comparison set, as adding other forms would not affect the outcome. On the one hand, we see that stem-stressed candidate (a) preserves paradigm uniformity with the member of the comparison set. As a result, (a) violates Anti-Ident. On the other hand, we see that suffix-stressed candidate (b) violates both PUall and PUnum, as it does not match the stress placement of the member of the comparison set. However, (b) does not violate Anti-Ident. Candidate (b) is correctly chosen as the winner, and contrast is maintained.

-

(17)

The ranking Anti-Ident ⪢ PUnum, PUall predicts a language in which stress is consistent in the paradigm by default. However, for every pair of homophonous suffixes, stress is predicted to differ between the two forms. When the two forms differ in number, the singular forms will match the stress assignment of the singular competitor and the plural forms will match the stress assignment of the plural competitor. This is the case with nominative plural ~ genitive singular homophony avoidance in Russian. When the two forms are of the same number, a mismatch in stress assignment within number will be tolerated. This is the case with prepositional singular ~ dative singular homophony avoidance.

Note once again that, while the three constraints employed are compatible with the data presented in this section, other grammars may also be compatible. Therefore, other constraints are required to explain the particulars of Russian accentuation. For example, it is unclear why the language prefers stem stress in the singular and suffix stress in the plural and not vice versa, since both scenarios satisfy Anti-Ident and PUnum. Also, while PUall correctly gives preference to accentual paradigms that preserve the same stress pattern throughout the paradigm, the fact that stable stress is far more common than end stress remains unexplained. Because these details have no bearing on homophony avoidance, they will not be explored further.

It should also be acknowledged that, although the corpus presents evidence of two anti-homophony trends in masculine nominals, Russian is not devoid of homophony. The aforementioned homophony between the dative singular /-u/ and secondary genitive singular /-u/ is one instance of homophony within Russian masculine nouns that is tolerated. In fact, among feminine and neuter nouns, homophony between the nominative plural and genitive singular is commonplace, e.g. feminine [ˈkoʂk-i] ‘cat (nom.pl/gen.sg)’ and neuter [ˈblʲud-a] ‘dish (nom.pl/gen.sg)’; these are the same grammatical cases that exhibit homophony avoidance in masculine nouns. Furthermore, note that at least one case of homophony avoidance involving the genitive plural and nominative singular suffixes has been found in feminine and neuter nouns (Pertsova Reference Pertsova2015). Therefore, homophony avoidance is not exclusive either to masculine forms or to the combinations of case and number explored here. Furthermore, homophony is tolerated in masculine forms and in the combinations of case and number explored here. As such, it is unclear how the locus of homophony avoidance is determined in the language.

Assuming that the patterns discussed in this section are the result of homophony avoidance, we can observe an important asymmetry between (13) and (16). Stress shifts motivated by homophony avoidance, as in (13) and (17), require only a single form in the comparison set, the potentially homophonous competitor. Stress shifts motivated by paradigm uniformity, as in (16), require multiple forms in the comparison set, a form of the same grammatical number and a homophonous competitor, which itself determines stress assignment on that form. In other words, the stress shift motivated by paradigm uniformity presupposes the stress shift motivated by homophony avoidance. The two kinds of stress shift require different amounts of data as motivation. This asymmetry will become crucial in the experimental design in §4.

A competing explanation, one that does not make reference to homophony avoidance, is possible. It could be the case either that the patterns observed are random or that they result from diachronic impulses, and that inflectional suffixes are stored in the lexicon along with information about the distribution of paradigm stress. In such an account, the underlying representation of the nominative plural suffix /-a/ must specify stress placement not only in the nominative plural, but also in other forms in the paradigm, specifically the singular, which always bears stress on the stem when the nominative plural suffix is /-a/; only in this way can we ensure co-occurrence of the suffix with the mobile stress pattern. The same is true of the underlying representation of the prepositional singular /-u/, which must store information about stress in other singular forms.

Importantly, in an account that does not make reference to homophony avoidance, there is nothing special about the link between the nominative plural /-a/ and the genitive singular /-a/. The stress placement of one can be reliably predicted from the other, but this is true of any two forms in the paradigm. Given the form [toˈm-a] ‘volume (nom.pl)’, one should be able to just as easily deduce the stress placement in [ˈtom-u] (dat.sg) or [ˈtom-om] (instr.sg), even though these are not potentially homophonous. It should be noted that, in any case, simple storage cannot explain why words in which the nominative plural and genitive singular suffixes match in stress tend to have suppleted stems in the plural.

The following section presents a nonce-word experiment, the aim of which is to ascertain which of the two approaches is correct: homophony avoidance or projection from the lexicon. Additionally, the experiment was designed to illustrate that the patterns observed in the corpus are productive and active in the synchronic grammar of speakers.

4 Experiment

The experiment was a nonce-word task (Berko Reference Berko1958), conducted online with Russian-speaking participants. Participants were tasked with assigning stress to the target, a nonce noun in one of the singular forms, after they had been shown the prompt, the same nonce noun in the nominative plural. The experiment was designed to see if stress assignment would be used as a disambiguation strategy in cases where the two morphologically different forms were potentially homophonous.

The experiment made use of the nominative plural ~ genitive singular homophony avoidance pattern described in §3.1. As participants were exposed to only a few forms of the paradigm, it manipulated the effects of homophony avoidance and paradigm uniformity separately, thereby distinguishing between true homophony avoidance and corpus mimicry: see §4.2 for more details.

4.1 Experiment method

4.1.1 Participants

A total of 107 participants took part in the experiment. Data from seven (6.5%) was removed, due to a greater than 10% error rate (wrong target case choice). Participants were recruited through Russian social media, forums and student unions and, upon completion, offered a payment of 300 roubles (approximately US$4.60 at the time of the experiment). Demographic information was self-reported. 79 of the participants were female, 20 were male (1 undeclared). The mean age of participants was 25.6 (median 22; range 15–65).

95 participants reported Russia as their country of birth. Forty were born in the Moscow region and nine in the Sverdlovsk region, with the remaining participants varying greatly in place of birth. 59 participants reported living in Moscow at the time of the experiment, and all but nine lived in Russia. Ninety participants reported some knowledge of English, 28 some knowledge of German and 21 some knowledge of French.

4.1.2 Stimuli

Two factors were manipulated in a 2 × 3 design: prompt suffix and target case. There were two experimental groups: the exposed group and the unexposed group. The groups shared the same fillers and most of the trials with critical items. However, only the exposed group was ever shown potentially homophonous prompt and target forms. Order in both groups was randomised by participant.

There were 72 items, 36 target and 36 filler. Each trial contained a unique nonce word. Nonce word stems were monosyllabic and constructed stochastically by a bigram learning model trained on the GICR corpus (see Albright Reference Albright2009 for a description of the model).Footnote 5 Nonce stems that sounded unnatural to the author were removed manually and replaced with newly generated ones. Nonce words in critical trials were always masculine, and suffix-stressed in the prompt; nonce words in filler trials varied in gender (masculine ~ feminine) and prompt stress (suffix ~ stem).Footnote 6 The 36 stems for the critical trials are listed in Table IV.Footnote 7

Table IV Nonce stems generated by bigram model for critical trials.

4.1.2.1 The experimental groups

Participants were split at random into two groups. During the experiment, the exposed group was occasionally given potentially homophonous combinations of prompt and target. The unexposed group acted as a control, and was never given potentially homophonous combinations of prompt and target. The task for both groups was to assign stress to the target form.

The target for the exposed group varied between the dative singular, the instrumental singular and the genitive singular. Recall that the latter is potentially homophonous with the nominative plural prompt. The target for the unexposed group varied between the dative singular, the instrumental singular and the prepositional singular. None of the target forms for the unexposed group could be homophonous with the prompt.

4.1.2.2 Prompt suffix

The prompt was always the nominative plural form of the same noun as the target. In critical trials, the prompt always had suffix stress. Because stress assignment for the plural forms was predetermined (recall that stress is generally consistent within plural and singular forms, but not between the two), participants, by assigning stress to the singular target, were choosing between an end stress pattern (suffix stress on the target) and a mobile stress pattern (stem stress on the target).

For critical items, the prompt varied between the two available nominative plural suffixes: /-i/, which is not homophonous with any singular form, and /-a/, which is potentially homophonous with the genitive singular. For filler items, the nominative plural suffix was always /-i/. The distribution of critical items by prompt, target and group is given in Table V.

Table V Number of critical items by factor.

Critical trials with potential homophony between the prompt and target constituted 1/12 of all trials for the exposed group (in bold in Table V), while the unexposed group did not see any such trials at all. The large number of non-homophonous trials and fillers was added to obscure the purpose of the experiment, and to avoid eliciting any prescriptive notions about contrast and stress.

4.1.3 Procedure

The experiment was conducted online, in Russian. All participants provided written consent for their participation in the experiment.

The stimuli were recorded by a male native speaker of Russian, in his late 40s, born in the Moldavian SSR and resident in Canada for the previous 18 years. For each item, the stimulus consisted of a sequence of three sentences, each of which was presented orthographically and auditorily. The orthographic representation of each sentence remained on screen for the remainder of the trial. For each item, a unique illustration of a fictional animal was displayed throughout the trial.Footnote 8

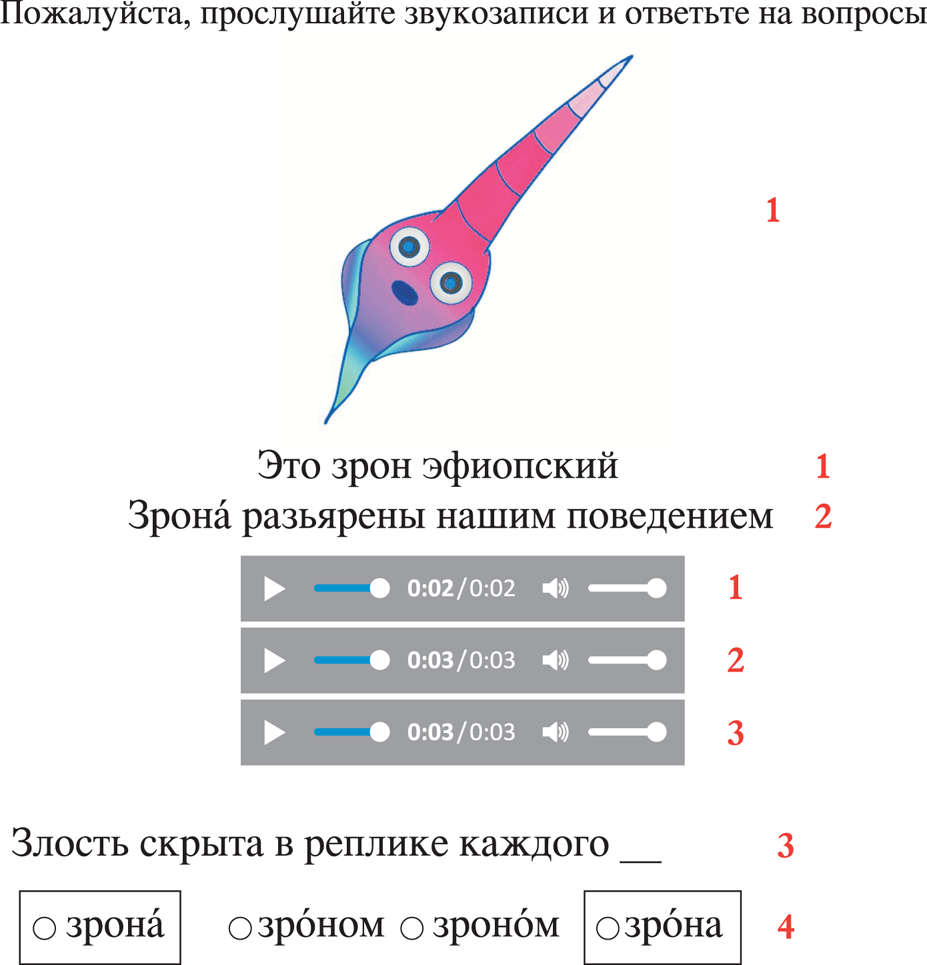

The first sentence was of the form ‘This is N + Adj’. The sentence presented a new nonce noun, followed by and agreeing with a new but real adjective. Recall that the homophony avoidance pattern is exclusive to masculine nouns. The first sentence was included to introduce the gender of the nonce word to the participant. The same nonce stem was used in the remainder of the trial. The second sentence presented the prompt form, i.e. the nominative plural of the nonce word. The third sentence contained a blank space, or silence in the recording, corresponding to the target form, i.e. the nonce word in one of the singular cases. After the final recording finished playing, a multiple-choice question appeared on the screen, in which participants were asked to fill in the gap in the last sentence. Two of the answers bore a case ending which was compatible with the sentence gap, and the other two a real but contextually illicit case ending. For both the felicitous and infelicitous answers, participants had to choose between a form with stress on the stem and a form with stress on the suffix. The order of answers was randomised by trial. Answers were presented orthographically, with stress marked with an acute accent, the standard indicator of stress in Russian. A sample trial is shown in Fig. 1. Illustrations, contexts for the second and third sentences, and adjectives in the first sentence varied by trial. In order to increase participant involvement, the context sentences were linked thematically and engaged with the illustration where possible. Each sentence was accompanied by a ‘Play’ button, allowing participants to listen to the recordings more than once. The trial ended once the ‘Next’ button was clicked.

Figure 1 Representation of the screenshot of a sample trial for the nonce item /zron/.

The translations of the text displayed on the screen are:

‘Please listen to the recordings and answer the questions.

This is an Ethiopian zron ([zron]).

Zroná ([zro'na]) are infuriated by our behaviour.

Anger is concealed in the statement of every —.

![]() zroná ([zro'na])

zroná ([zro'na]) ![]() zrónom ([’zronom])

zrónom ([’zronom]) ![]() zronóm ([zro'nom])

zronóm ([zro'nom]) ![]() zróna ([’zrona])’

zróna ([’zrona])’

The intended response was zrona. The numbers, which represent the order in which the items appeared on screen, and the outline highlighting the felicitous answers were not present in the original experiment, and are included for exposition.

4.2 Predictions

Table VI contains the nominative plural suffix and singular target stress assignment combinations possible in the experiment. Frequency by nominative plural suffix, derived from Table II, is also provided. Recall that the combination of suffix stress in the plural and stem stress in the singular (mobile stress) is extremely rare in the corpus when the nominative plural suffix is /-i/, whereas the combination of suffix stress in the plural and suffix stress in the singular (end stress) is extremely rare in the corpus when the nominative plural suffix is /-a/.

Table VI Possible combinations of stress pattern and the nominative plural suffix for critical trials.

4.2.1 Projection from the lexicon

The baseline hypothesis of the experiment is that participants will simply mimic the patterns observed in the corpus. This hypothesis is compatible with the idea that homophony avoidance is diachronic and emergent (Blevins & Wedel Reference Blevins and Wedel2009, Mondon Reference Mondon2010).

If speakers simply memorise the distributions of stress and suffix, then, as in Table VI, trials with /-a/ as the prompt suffix should elicit a greater proportion of stem stress on the target, while trials with /-i/ as the prompt suffix should elicit a greater proportion of suffix stress. Crucially, these expectations hold regardless of the grammatical case of the target, as the corpus pattern is independent of grammatical case. In other words, this account predicts an effect of prompt suffix on the dependent variable, but no effect of target case or any interaction of the two.

No difference between exposure groups is predicted under this approach. The potentially homophonous prompt/target pairs occasionally given to the exposed group are not predicted to behave any differently from non-homophonous pairs. Like the exposed group, the unexposed control group is predicted to display an association between the /-a/ nominative plural and mobile stress and between the /-i/ nominative plural suffix and end stress.

4.2.2 Homophony avoidance

The alternative hypothesis is that participants’ answers are motivated by homophony avoidance. We can model the precise predictions of this hypothesis in OT. The central assumption of the experimental design is that the comparison set can only contain forms which have been witnessed previously. As all of the items in this experiment are nonce words, the comparison set is limited to the one form previously given to the participant: the prompt.

Under this approach, the stress assignment of the genitive singular target in combination with a prompt bearing the /-a/ nominative plural suffix is predicted to behave like real words in the corpus, as modelled in (18) for the nonce stem /zron/. Due to the presence of the nominative plural prompt in the comparison set, the suffix-stressed candidate (b) violates Anti-Ident, and (a) is the winner.

-

(18)

Contrast this with a dative singular target in combination with the /-a/ prompt, as in the nonce stem /rʲist/ in (19). This input is predicted to behave differently from the stem in (17), and indeed from real words in the corpus (cf. (16)).

-

(19)

Because the potentially homophonous genitive singular form was not made available to the participants, it did not incur a violation of Anti-Ident, which would have led to stem stress. Without a stem-stressed genitive singular form in the comparison set, there is no violation of PUnum for the dative singular and no motivation for stem stress in the singular. In fact, unlike real words, the experimental items cannot incur a violation of PUnum, as participants were only ever shown one form in the singular and one form in the plural. Note that tableaux for trials bearing the /-i/ nominative plural suffix are similar to (19), as these too cannot violate either Anti-Ident or PUnum.

Therefore, under the homophony avoidance hypothesis, stress assignment is predicted to be asymmetric with respect to target case. For trials where the prompt bears the /-a/ suffix and the target case is genitive, a greater proportion of stem stress on the target (mobile stress) is predicted. Yet, contrary to patterns observed in the corpus, for trials where the prompt bears the /-a/ suffix and the target case is not genitive, a greater proportion of suffix stress on the target (end stress) is predicted. In other words, a homophony avoidance account predicts an effect of the interaction of prompt suffix and target case on the dependent variable, but no simple effects of either.

Under this approach, the two groups should behave differently. The unexposed group is predicted not to exhibit any effect, despite the fact that the nominative plural suffix and stress pattern are correlated in the corpus.

4.3 Experiment results

4.3.1 Descriptive patterns

The 100 participants each contributed 36 critical items and 36 fillers. Errors due to infelicitous choice of target case (N = 88) were removed from the analysis. There were 46 participants in the exposed group and 54 in the unexposed group. The distribution between the groups was uneven because the study was conducted online, without human intervention. Therefore, results will be presented as proportions and not counts.

As can be seen in Fig. 2, participants preferred to keep stress on the suffix, with only 38.6% of overall responses corresponding to stem stress in the target and, therefore, a mobile stress pattern. This asymmetry is expected, since end stress is far more common than mobile stress, as found in §3.

Figure 2 Percentage of target stem stress (mobile stress pattern) responses by target case and prompt suffix, aggregated across participants in the exposed group (N=46). Here and below, whiskers span a 95% confidence interval, calculated as 1.96 X Standard Error.

For all three target cases, an /-a/ prompt suffix elicited a greater proportion of mobile stress assignment. The difference in prompt suffix was most pronounced in the genitive target, which elicited 37.7% mobile stress responses with the /-i/ prompt suffix and 62.8% mobile stress responses with the /-a/ prompt suffix. In fact, the combination of /-a/ prompt suffix and genitive singular target case was the only one which elicited a mobile stress response more than half of the time. For instrumental targets, trials with the /-a/ prompt suffix still elicited a notable increase in mobile stress, from 27.1% to 38.0%. For dative targets, the effect was in the same direction, rising from 36.2% mobile stress with the /-i/ suffix to 42.2% in the /-a/ suffix.

For the unexposed group, as can be seen in Fig. 3, the differences are less pronounced. No combination of prompt suffix and target case elicited a greater than 50% proportion of mobile stress. For instrumental and dative target cases, as for the exposed group, the /-a/ prompt suffix elicited an increase in mobile stress responses: from 28.3% to 35.7% in the instrumental target and from 38.7% to 42.9% in the dative target. However, for the prepositional singular, which was not given to the exposed group, the difference was miniscule and in the opposite direction, with the /-a/ prompt suffix eliciting a mobile stress response 37.2% of the time and the /-i/ prompt suffix 38.3%.

Figure 3 Percentage of target stem stress (mobile stress pattern) responses by target case and prompt suffix, aggregated across participants in the unexposed group (N=54).

The initial results seem to point to a slight effect of prompt suffix on stress assignment and a substantial effect of prompt suffix in the genitive target in particular. For both trends, the effect is in the expected direction, with the /-a/ nominative plural suffix eliciting a greater proportion of mobile stress responses. The slight overall effect of prompt suffix is in line with the projection from the corpus hypothesis. The large effect in the genitive singular target is in line with the homophony avoidance hypothesis.

4.3.2 Inferential statistics

To determine if the observed trends were statistically significant, a logistic regression model was run in R (R Core Team 2019), using the lme4 package (Bates et al. Reference Bates, Mächler, Bolker and Walker2015). The analysed data consisted of critical items only, with errors (N = 88) removed. The dependent variable was target stress assignment (reference level: end stress). The independent variables were target case (reference level: genitive) and prompt suffix (reference level: /-i/); both were sum coded. Participant and item were included as random effects. By-suffix slope per participant was also included in the model. To ensure model convergence, all other random effect slopes were omitted. Models for the exposed group and unexposed groups were run separately, due to the non-isomorphic distribution of target case between them. The model formula was as in (20).Footnote 9

-

(20)

Results from the exposed group model are presented in Table VII.

Table VII Results of the generalised linear regression model for the exposed group.

Positive estimates correspond to an increase in mobile stress probability in the target, and negative estimates correspond to an increase in end stress probability. The difference between genitive and instrumental case was significant, with more mobile stress for genitive targets than for instrumental targets. Suffix choice for the reference level (genitive) was found to be highly significant, with more mobile stress for /-a/ suffix prompts than for /-i/ suffix prompts. Finally, the interaction between prompt suffix and target case was significantly different between genitive and dative targets, but not between genitive and instrumental targets.

The results of the model indicate a significant effect of suffix. However, it is important to differentiate between an overall effect of prompt suffix and an effect of the suffix in the reference level. A post hoc test on the model interactions was therefore run, using the phia package in R (De Rosario-Martinez et al. Reference De Rosario-Martinez and Fox2015). Target case was set as a fixed comparison, while prompt suffix was set as the pairwise comparison. Results of the interaction test are given in Table VIII. The difference between /-i/ suffix prompts and /-a/ suffix prompts was significant for genitive targets, but not for dative and instrumental targets. Therefore, an across the board effect of prompt suffix is unsubstantiated. I conclude that the /-a/ prompt suffix elicited an increase in mobile stress assignment in genitive targets, but not anywhere else.

Table VIII Results of the interaction test for the exposed group model.

Each trial, i.e. each combination of item and participant, was assigned the log odds of receiving a stem response based on model coefficients using R's predict() function. The log odds were converted to probabilities and used to analyse individual differences between participants, as shown in Fig. 4. The figure shows the likelihood of a mobile stress response per participant in the exposed group, plotted by prompt suffix and target case. There was considerable individual variation in responses. Some participants strongly preferred end stress for all items, while others strongly preferred mobile stress for all items. However, for 44 of the 46 participants in the exposed group there was an increase in likelihood of mobile stress when going from the /-i/ suffix to the /-a/ suffix in the genitive target, corresponding to a higher probability of mobile stress responses in the potentially homophonous combination of target and prompt.

Figure 4 Model predictions for individual participants in the exposed group, by target case and prompt suffix. The y-axis represents the probability of choosing a stem response. Each line segment is a participant (N=46).

Results from the logistic regression model for the unexposed control group are presented in Table IX. No main effect or interaction was found to be significant for the unexposed group.

Table IX Results of the generalised linear regression model for the unexposed group.

The experimental results support the homophony avoidance hypothesis. Participants who were exposed to potential homophony were significantly more likely to assign mobile stress to the target when doing so would disambiguate it from the prompt. In other words, participants had acquired the association between the /-a/ nominative plural suffix and singular stem stress assignment in the genitive case, but not the dative or instrumental, despite all three cases exhibiting the same pattern in the corpus. The results can be observed for 44 of the 46 participants in the exposed group. Participants who were not exposed to potential homophony displayed no significant effect.

5 General discussion and conclusion

It is important to once again highlight the fact that the experiment results cannot be predicted simply based on corpus trends. As discussed in §3.1, in the corpus a stressed nominative plural /-a/ co-occurs with a mobile stress pattern (in all words but one), i.e. stem stress in the singular and suffix stress in the plural. Therefore, based on corpus trends alone, when given a nominative plural form like [zroˈn-a], participants were expected to consistently assign stem stress to any singular form, such as the dative singular [ˈzron-u]. However, this was not observed in the experiment. Instead, participants overwhelmingly assigned stem stress to a singular form when doing so would disambiguate it from the prompt, but maintained suffix stress elsewhere.

As shown in §3.3 and §4.2.2, the same association of the /-a/ nominative plural with a mobile stress pattern can be modelled in OT, as a combination of homophony avoidance (Anti-Ident), which ensures that the nominative plural and genitive singular have different stress, and paradigm uniformity, which ensures that singular forms mimic the stress of the genitive singular, while plural forms mimic the stress of the nominative plural. The experiment, which did not provide participants with any singular form except for the target, by-passed paradigm uniformity entirely. Thus, without relevant members in the comparison set, only a homophony avoidance effect could be manifested. The use of nonce words in the experiment was crucial. Contrary to nonce words, real words are expected to be affected by paradigm uniformity, as the entire inflectional paradigm is familiar to the speaker.

Because a diachronic and emergent mechanism for homophony avoidance is well established in the literature (Blevins & Wedel Reference Blevins and Wedel2009, Mondon Reference Mondon2010), and because speakers are able to extend trends found in the lexicon to novel words, any faithful projection of corpus patterns to nonce data does not provide sufficient evidence for synchronic homophony avoidance. A homophony avoidance pattern could have emerged in the language due to errors in transmission, and speakers could have faithfully internalised the pattern, as an association between elements rather than as an active restriction. To reliably measure a synchronic homophony avoidance effect, we must induce homophony avoidance behaviour not found in the language, for example by using nonce words. To do this, we need a language where the behaviour of real words is determined by homophony avoidance and another factor, as well as an experiment where the effects of this other factor can be isolated. Russian is such a case. Due to the interaction of homophony avoidance and paradigm uniformity in the grammar, in certain constructed situations speakers of Russian displayed biases not found in their language. While the experimental paradigm presented in this paper can in theory be extended to other cases of alleged homophony avoidance, the interaction of homophony avoidance and another factor is needed to adequately demonstrate that a homophony avoidance generalisation is synchronic and not diachronic. Without such an interaction, any results are ambiguous, as they can just as easily be ascribed to a combination of diachronic homophony avoidance and pattern learning.

Technically speaking, results from the experiment only show that speakers of Russian can shift stress in the genitive singular to avoid homophony with the nominative plural. The reverse, i.e. a shift in the nominative plural to avoid homophony with the genitive singular, was not demonstrated experimentally. This is an artefact of the experimental design rather than an insight into Russian phonology. However, there is no reason to assume that speakers are unable to apply homophony avoidance in both directions.

In fact, evidence from diachrony seems to imply that it is the nominative plural that undergoes the shift to avoid homophony with the genitive singular, as in (13) and (15). Recall that many forms with mobile stress and the /-a/ nominative plural used to have stable stress and the /-i/ nominative plural: compare modern Russian [toˈm-a] with archaic Russian [ˈtom-i] ‘volume (nom.pl)’. Therefore, the singular paradigm remained unchanged historically, while the plural forms underwent a shift from stem-stressed to suffix-stressed. This is the reverse direction from the one tested in the experiment. If the historical development in the language is a reliable indicator of the synchronic homophony avoidance mechanism, then the experiment further demonstrates that speakers are able to generalise the mechanism and apply homophony avoidance in the opposite direction as well.

More broadly, the results of the experiment indicate that the synchronic homophony avoidance effect is not only present and productive in the language, but also that it is salient enough to be extended to nonce words. Previous results have shown that natural or phonologically motivated generalisations observed in the lexicon are more likely to be extended to nonce words (Becker et al. Reference Becker, Ketrez and Nevins2011, Hayes & White Reference Hayes and White2013). Therefore, at the very least, the findings of this project suggest that homophony avoidance should be considered a typologically natural phenomenon.

Tangential to homophony avoidance, but crucial to the experiment design, is the secondary finding that the comparison set, at least for homophony avoidance, is limited to forms that are familiar to the speaker. It is not the case that, after witnessing a single form, the speaker populates the comparison set with the entire inflectional paradigm of that form.

Therefore, there is no evidence to suggest that the comparison set for Anti-Ident can be greater than the inflectional paradigm for synchronic homophony avoidance. Frameworks dealing with contrast more generally, such as Preserve Contrast Theory (Łubowicz Reference Łubowicz2012, Reference Łubowicz2016), utilise broader comparison sets, even those containing nonce stems themselves. However, because the OT modelling in §3.3 and §4.2.2 imposes a strict limit on the comparison set, and because other literature on homophony avoidance has also found that the phenomenon is limited to the inflectional paradigm (Baerman Reference Baerman2010, Bethin Reference Bethin2012, Kaplan & Muratani Reference Kaplan and Muratani2015, Pertsova Reference Pertsova2015), I conclude that homophony avoidance has a narrower scope in the grammar than in contrast preservation more generally. Frameworks that deal with contrast in other domains, such as Dispersion Theory (Ní Chiosáin & Padgett Reference Ní Chiosáin, Padgett and Parker2010, Flemming Reference Flemming and Aronoff2017) and Preserve Contrast Theory, although they differ from the current study in empirical coverage, also suggest the existence of a synchronic contrast preservation mechanism, and are, therefore, complementary to this study, rather than contradicting it.

This paper introduces a pattern of homophony avoidance in the Russian nominal paradigm which must be attributed to a synchronic restriction against homophony. The existence of a synchronic anti-homophony constraint has been previously regarded as unsubstantiated (King Reference King1967, Mondon Reference Mondon2009, Sampson Reference Sampson2013, Kaplan & Muratani Reference Kaplan and Muratani2015). I believe the main reason for the scepticism is the well-established framework for diachronic homophony avoidance and the lack of a clear method of distinguishing between diachronically emergent contrast preservation and a synchronic anti-homophony constraint. This paper shows not only that synchronic homophony avoidance is possible, but that, given the right circumstances, it can be discriminated from emergent patterns experimentally. The paradigm presented here may prove useful in testing similar phenomena in other languages, and it is to be hoped that more instances of synchronic homophony avoidance will be uncovered in the future. These findings contribute to the understanding of phonological and morphological grammar in general and may also be useful to the study of Russian in particular.